Abstract

An emerging body of evidence indicates that PGE2 has a privileged anti-inflammatory role within the airways. Stimulants of protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2) inhibit airway smooth muscle tone in vitro and in vivo predominantly via cyclooxygenase (COX)-dependent generation of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Thus, the current study tested the hypothesis that PAR2-induced generation of PGE2 inhibits the development of allergic airways inflammation and hyperresponsiveness.

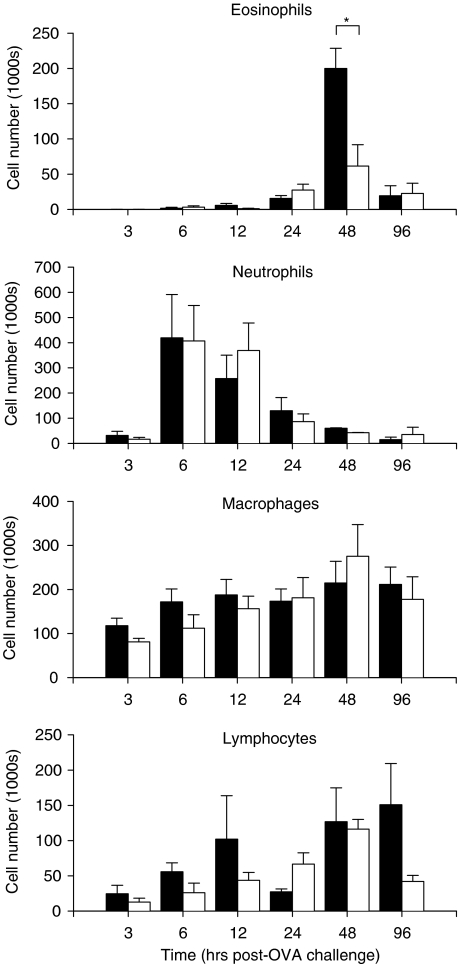

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid recovered from ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitised and -challenged (allergic) mice contained elevated numbers of eosinophils, which peaked at 48 h postchallenge. Intranasal (i.n.) administration of a PAR2-activating peptide (PAR2-AP) SLIGRL (25 mg kg−1, at the time of OVA challenge) caused a 70% reduction in the numbers of BAL eosinophils (compared to the scrambled peptide LSIGRL, 25 mg kg−1).

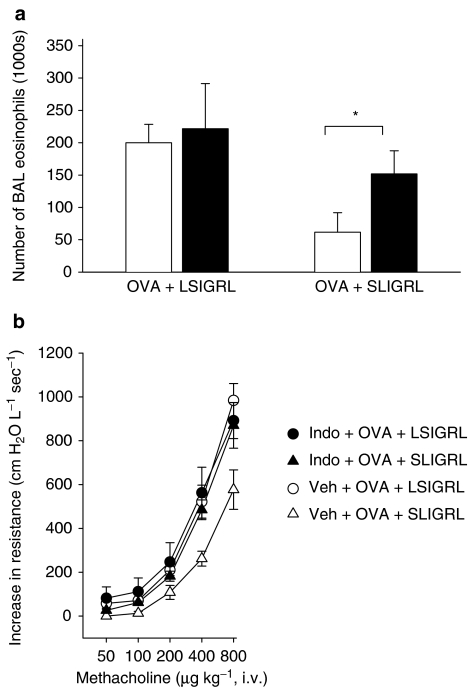

Pretreatment of allergic mice with either indomethacin (1 mg kg−1, dual COX inhibitor) or nimesulide (3 mg kg−1, COX-2-selective inhibitor) blocked SLIGRL-induced reductions in BAL eosinophils.

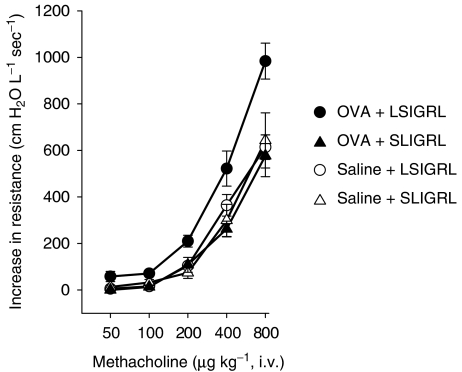

I.n. SLIGRL, but not LSIGRL, inhibited the development of antigen-induced airways hyperresponsiveness. The inhibitory effect of SLIGRL was blocked by indomethacin.

Exposure of isolated tracheal preparations from allergic mice to 100 μM SLIGRL was associated with a 5.0-fold increase in PGE2 levels (P<0.05, compared to 100 μM LSIGRL). SLIGRL induced similar increases in PGE2 levels in control mice (OVA-sensitised, saline-challenged).

I.n. administration of PGE2 (0.15 mg kg−1) to allergic mice significantly inhibited eosinophilia and airways hyperresponsiveness to methacholine.

In anaesthetised, ventilated allergic mice, SLIGRL (5 mg kg−1, i.v.) inhibited methacholine-induced increases in airways resistance. Consistent with this bronchodilator effect, SLIGRL induced pronounced relaxation responses in isolated tracheal preparations obtained from allergic mice. LSIGRL did not inhibit bronchomotor tone in either of these in vivo or in vitro experiments.

In summary, a PAR2-AP SLIGRL inhibited the development of airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness in allergic mice through a COX-dependent pathway involving COX-2-mediated generation of the anti-inflammatory mediator PGE2. SLIGRL also displayed bronchodilator activity in allergic mice. These studies support the concept that PAR2 exerts predominantly bronchoprotective actions within allergic murine airways.

Keywords: Protease-activated receptor; allergic inflammation; airway hyperresponsiveness; eosinophils; SLIGRL; cyclooxygenase, prostaglandin E2; indomethacin; bronchoalveolar lavage

Introduction

Protease-activated receptors are a novel group of G-protein-coupled, seven transmembrane domain receptors, whose activation is dependent on the proteolytic cleavage of the amino-terminus of the receptor. The newly formed amino-terminus of the receptor then functions as a tethered ligand, interacting with the second extracellular loop of the receptor to activate cell-signalling events. Four protease-activated receptors (PARs) have been cloned and characterised; PAR1 and PAR3 are preferentially activated by thrombin, PAR2 by trypsin and PAR4 by trypsin and thrombin. PAR2 is also activated by a range of other proteases, including tryptase (Mirza et al., 1997) and the coagulation-related proteases, factors VIIa and IXa (Camerer et al., 2000; Kawabata et al., 2001). Tryptase, in particular, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of allergic airways inflammation (He & Walls, 1997; Krishna et al., 2001).

However, there is conflicting evidence as to whether the activation of PAR2 promotes or opposes the progression of airway inflammatory responses. Schmidlin et al. (2002) evaluated the role of PAR2 in allergic inflammation of the airway by using genetically modified mice either lacking or overexpressing PAR2. Deletion of PAR2 was associated with diminished inflammatory cell infiltration and reduced airway hyper-reactivity, whereas overexpression of PAR2 exacerbated both the infiltration of eosinophils cells into the lumen and the hyper-reactivity of the airway. In contrast, Moffatt et al. (2002) reported that a PAR2-activating peptide (PAR2-AP) SLIGRL inhibited bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced neutrophil influx into mouse airways, suggesting that PAR2 agonists may be useful anti-inflammatory therapeutic molecules in airway inflammatory diseases.

Within the respiratory tract, PARs are expressed by structural cells, such as epithelial and smooth muscle cells, as well as by migratory cells such as macrophages, eosinophils, lymphocytes and mast cells (Lan et al., 2002). Of particular interest, activation of PARs stimulates the release of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from epithelial cell cultures and intact airway preparations. The release of PGE2 from the epithelium appears to play a fundamental role in the airway smooth muscle relaxant responses induced by PAR-APs because PAR1-, PAR2- and PAR4-mediated relaxation responses are blocked by indomethacin, a cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor (Cocks et al., 1999; Chow et al., 2000; Lan et al., 2001). In addition to its bronchorelaxant activity, PGE2 also appears to have a privileged role in limiting the immune-inflammatory response and tissue repair processes in the lung (Vancheri et al., 2004). This raises the possibility that PAR-induced generation of PGE2 may exert anti-inflammatory effects within the airways.

In the current study, we tested the hypothesis that SLIGRL, a PAR2-AP, attenuates the development of airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of acute allergic inflammation via a COX- and PGE2-dependent pathway.

Methods

Allergen sensitisation and challenge of mice

Male BALB/c mice at 6 to 8 weeks of age were purchased from the Animal Resources Centre (Murdoch, Australia) and housed under pathogen-free conditions (University of Western Australia, Australia). Food and water were available ad libitum. On days 0 and 14 of the study, mice were given an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 100 μg ovalbumin (OVA) and 2.25 mg Al(OH)3 in 0.3 ml of sterile saline. In addition, on day 14 mice were anaesthetised (methoxyflurane) and given an intranasal (i.n.) instillation of 25 mg kg−1 OVA in 25 μl of sterile saline. On day 28, OVA-sensitised mice were anaesthetised (methoxyflurane) and given a single i.n. challenge with 500 μg OVA (in 25 μl, allergic mice) or saline (nonallergic mice). The procedures outlined in the current study were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Western Australia.

Drug administration

To investigate the effects of selected agents on the development of airway eosinophilia (determined by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)) and airway hyperresponsiveness (determined by lung function recording), drugs were coadministered with the i.n. inoculate of OVA or saline administered on day 28 (see above). Drugs included the PAR2-AP, SLIGRL (0.25 or 25 mg kg−1, Proteomics International, Australia), a control, scrambled peptide, LSIGRL (0.25 or 25 mg kg−1, Proteomics International, Australia) and PGE2 (0.15 mg kg−1, Caymen Chemicals, U.S.A.). Some mice were given a COX inhibitor, indomethacin (1 mg kg−1, i.p.), nimesulide (3 mg kg−1, i.p.) or saline (i.p.) 1 h before peptide administration on day 28.

Bronchoalveolar lavage

At selected times postchallenge, mice were killed (250 mg kg−1 pentobarbitone i.p., Rhone Merieux Australia Pty Ltd, Australia) and a teflon canula inserted into the trachea. Lungs were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (5 × 0.5 ml). Total leucocyte number was calculated using a haemocytometer, and differential cell counts of macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils were performed on cytospin preparations (Shandon, U.S.A.) stained with Diff-Quick (Lab Aids Pty Ltd, Australia). Between 200 and 250 cells were counted on each cytospin preparation.

Lung function recording

At 48 h postchallenge, mice were anaesthetised (ketamine 130 mg kg−1 and xylazine 13 mg kg−1, i.p. injection) and the left jugular vein was cannulated for intravenous (i.v.) drug administration. The trachea was cannulated and connected to a pneumotachograph (Fleisch, Switzerland). Measurement of transpulmonary pressure was facilitated by insertion of a water-filled cannula into the middle thorax via the oesophagus. Autonomous breathing was abolished by administration of pancuronium bromide (450 μg kg−1, i.v.) and mice were ventilated (150 breaths min−1, 3.5 ml kg−1). Breath-to-breath changes in airway resistance (cm H2O l−1 s−1) were recorded (model PR8000, Mumed, U.K.) according to the principles of Amdur and Mead. Increasing doses of methacholine (50, 100, 200, 400 and 800 μg kg−1) were administered at 5 min intervals by i.v. injection via the jugular vein.

PGE2 enzyme immunoassay

On day 28, selected mice were killed and the trachea removed. Isolated tracheal ring preparations (3–4 mm in length) were suspended between two stainless-steel hooks at a tension of 0.3–0.4 g in a 1 ml organ bath containing Krebs-bicarbonate solution (in mM: NaCl 117, KCl 5.4, MgSO4·7H2O 1.3, KH2PO4 1.0, NaHCO3 25, CaCl2 2.5 and glucose 11.1) maintained at 37°C and bubbled with 5% CO2 in O2. Changes in isometric tension were detected (FTO3 transducers, Grass Instruments, U.S.A.) and recorded using custom-built amplifiers and computer software. Tracheas were precontracted with carbachol (1 μM, Sigma Chemical Co., U.S.A.), and 5 min later exposed to 100 μM SLIGRL or LSIGRL. Aliquots of bath fluid (50 μl) were collected 10 min after peptide administration and assayed for PGE2 content using an enzyme immunoassay kit (Caymen Chemicals, U.S.A.). PGE2 content was standardised to the wet weight of tracheal tissue (pg PGE2 mg tracheal tissue−1).

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and where appropriate, a modified t-test was used to determine differences between individual groups. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data are expressed as mean±s.e.m.

Results

Effect of SLIGRL on BAL fluid cell number and composition

As expected, the i.n. administration of OVA (together with control peptide LSIGRL) to OVA-sensitised mice on day 28 induced marked time-dependent changes in the number and type of leucocytes recovered by BAL (Figure 1). OVA challenge produced an early and robust rise in neutrophil number, which peaked at around 6 hours (Figure 1). Following this, a peak increase in eosinophil number was observed at 48 h, which partially resolved by 96 h. Numbers of lymphocyte and macrophages appeared to increase gradually over the 96 h, postchallenge period.

Figure 1.

Numbers of eosinophils, neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes in BAL fluid recovered from OVA-sensitised mice at 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 and 96 h after i.n. challenge with OVA and LSIGRL (25 mg kg−1, black columns) or OVA and SLIGRL (25 mg kg−1, white columns). Shown are the mean±s.e.m. values obtained from nine mice per group at each time point. *P<0.05.

A similar time profile was observed in OVA-sensitised mice that received an i.n. instillation of 25 mg kg−1 SLIGRL and OVA on day 28, with peak neutrophil and eosinophil numbers occurring at 6–12 and 48 h, respectively. However, BAL fluid from SLIGRL-treated mice contained 70% fewer eosinophils than LSIGRL-treated allergic mice (62 × 103±30 × 103 thousand versus 200±28 thousand eosinophils, n=9 mice) at the peak, 48 h time point (P<0.05, Figure 1). The significantly smaller number of eosinophils recovered 48 h postchallenge from SLIGRL-treated allergic mice was not due to a delay in the influx of eosinophils because eosinophil numbers declined to baseline levels by the 96 h time point (Figure 1). Numbers of neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes were similar in SLIGRL- and LSIGRL-treated allergic mice.

BAL recovered from OVA-sensitised mice challenged with saline (nonallergic mice), contained only very low numbers of eosinophils (less than 1% of total cell number at each of the 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 and 96 h time points; n=4–5 mice per time point), irrespective of whether they had received a 25 mg kg−1 i.n. dose of LSIGRL (1.0 × 103±1.0 × 103 thousand eosinophils at 48 h time point, n=4) or SLIGRL (2.3±0.4 thousand eosinophils at 48 h time point, n=4).

A lower dose of SLIGRL (0.25 mg kg−1, i.n.) had no significant effect on total BAL cell number or on the relative proportions of cells recovered from allergic mice (% eosinophils; 46.3±13.4 for SLIGRL-treated allergic mice versus 49.2±7.5 for LSIGRL-treated allergic mice; n=4 mice/group; 48 h time point).

Effect of SLIGRL on the development of airway hyperresponsiveness

I.v. administration of methacholine induced dose-dependent increases in airway resistance (Figure 2). OVA-sensitised mice that received a single i.n. challenge of OVA on day 28 (OVA+LSIGRL) were more responsive to methacholine than saline-challenged, OVA-sensitised mice (saline+LSIGRL, Figure 2). In contrast, OVA-sensitised mice challenged with i.n. SLIGRL (25 mg kg−1) and OVA (OVA+SLIGRL) did not exhibit airways hyperresponsiveness to methacholine (Figure 2). Administration of 25 mg kg−1 SLIGRL alone (saline+SLIGRL) did not inhibit airways responsiveness to methacholine (compared with 25 mg kg−1 saline+LSIGRL).

Figure 2.

Methacholine-induced increases in airway resistance determined in OVA-sensitised mice challenged with OVA (closed symbols) or saline (open symbols) solutions containing either SLIGRL (25 mg kg−1, triangles) or LSIGRL (25 mg kg−1, circles). In these studies, in vivo lung function was determined 48 h postchallenge. Shown are the mean±s.e.m. values obtained from four mice per group.

Effect of COX inhibitors on SLIGRL-induced responses

To investigate whether SLIGRL inhibited the development of airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness in allergic mice via a COX-dependent mechanism, additional experiments were conducted using indomethacin. Pretreatment of OVA+LSIGRL mice with indomethacin (1 mg kg−1) had no significant effect on the numbers of eosinophils recovered from BAL fluid (Figure 3a). However, indomethacin did significantly blunt the inhibitory effect of SLIGRL, such that the number of eosinophils in indomethacin-treated OVA+SLIGRL mice was not significantly different from OVA+LSIGRL mice (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Groups of OVA-sensitised mice were pretreated with indomethacin (1 mg kg−1, i.p.), or saline (i.p.), and 1 h later i.n. challenged with an OVA solution containing either LSIGRL or SLIGRL. After 48 h, BAL (a) and in vivo lung function testing (b) were performed. In (a), indomethacin-treated mice are shown as black columns and saline-treated mice as white columns. In (b), methacholine-induced increases in airways resistance were determined in indomethacin-treated allergic mice (closed symbols) given LSIGRL (circles) or SLIGRL (triangles), and saline-treated allergic mice (open symbols) given LSIGRL or SLIGRL. Shown are the mean±s.e.m. values obtained from four to nine mice per group. *P<0.05.

Pretreatment of the hyper-responsive OVA+LSIGRL mice with indomethacin (1 mg kg−1) was not associated with any change in responsiveness to methacholine (Figure 3b). In contrast, pretreatment of OVA+SLIGRL mice with indomethacin was associated with significant increase in the responsiveness to methacholine (Figure 3b), comparable to that seen in the hyper-responsive OVA+LSIGRL mice. Thus, pretreating mice with indomethacin markedly reduced the capacity of SLIGRL (25 mg kg−1) to inhibit the development of airway hyperresponsiveness.

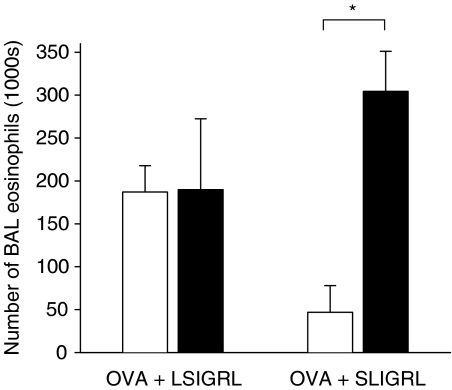

Pretreatment of OVA+LSIGRL mice with nimesulide (3 mg kg−1) had no significant effect on the numbers of eosinophils recovered from BAL fluid (Figure 4). However, nimesulide abolished the inhibitory effect of SLIGRL, such that the number of eosinophils in nimesulide-treated OVA+SLIGRL mice was not significantly different from OVA+LSIGRL mice (Figure 4). Neither nimesulide nor indomethacin had any significant effect on the numbers or types of cells present in the BAL fluid from nonallergic mice (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Groups of OVA-sensitised mice were pretreated with nimesulide (3 mg kg−1, i.p., black columns), or saline (i.p., white columns), and 1 h later i.n. challenged with an OVA solution containing either LSIGRL (OVA+LSIGRL) or SLIGRL (OVA+SLIGRL). Shown are numbers of BAL eosinophils recovered 48 h later (mean±s.e.m. values obtained from four to six mice per group). *P<0.05.

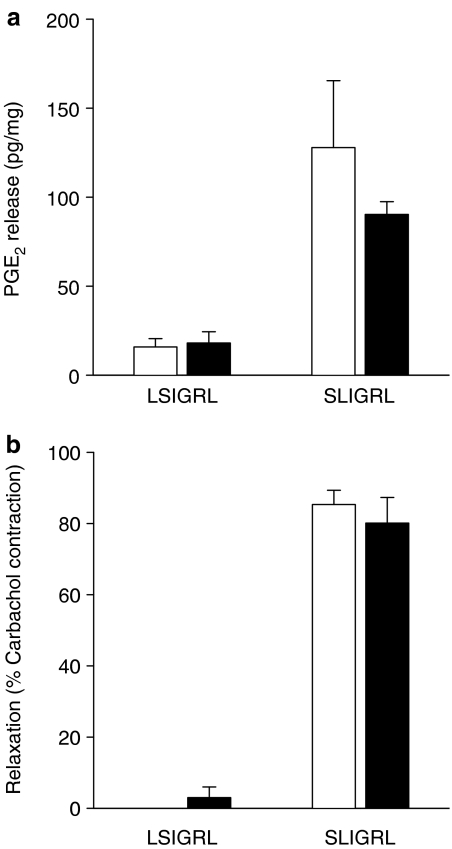

Effect of SLIGRL on PGE2 release from isolated airways

Experiments using indomethacin indicate that the inhibitory effects of SLIGRL on the development of airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness are mediated by a COX product. Consistent with this, tracheal preparations isolated from allergic mice exposed to 100 μM SLIGRL released 5.0-fold more PGE2 than those exposed to 100 μM LSIGRL (Figure 5a). This was not statistically different from the 8.1-fold increase in PGE2 levels induced by 100 μM SLIGRL in preparations from nonallergic mice (Figure 5a). In these experiments, SLIGRL caused pronounced relaxation responses in tracheal preparations isolated from both allergic and nonallergic mice (80.0±7.2% relaxation and 85.3±4.0% relaxation, respectively, of carbachol-induced contraction; Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Mouse isolated tracheal preparations were exposed for 10 min to 100 μM SLIGRL or the control peptide LSIGRL, and (a) PGE2 release and (b) relaxation responses determined. Shown are the mean±s.e.m. values obtained in preparations from four nonallergic mice (white columns) and four allergic mice (black columns).

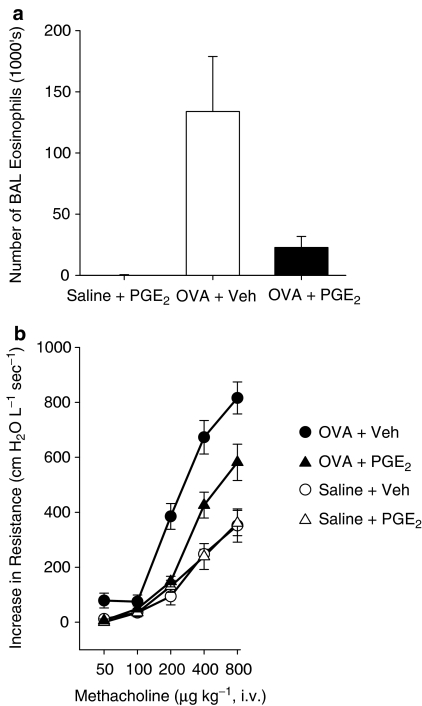

Effect of exogenous PGE2 on airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness

To evaluate whether the effects of SLIGRL on airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness is mimicked by PGE2, groups of allergic and nonallergic mice were administered 0.15 mg kg−1 PGE2 by i.n. instillation on day 28. As shown in Figure 6a, allergic mice treated with PGE2 (OVA+PGE2 mice) had significantly fewer eosinophils in BAL fluid recovered at 48 h than untreated allergic mice (OVA+vehicle mice). PGE2 also inhibited the development of airways hyperresponsiveness. OVA+PGE2 mice were significantly less responsive to methacholine than OVA+vehicle mice (Figure 6b). In nonallergic mice, PGE2 had no significant effect on either the number of eosinophils in BAL fluid or the airway responsiveness to methacholine.

Figure 6.

(a) Numbers of eosinophils in the BAL fluid recovered from OVA-sensitised mice 48 h after i.n. challenge with OVA and PGE2 (0.15 mg kg−1, black column) or with OVA and vehicle (white column). Shown are the mean±s.e.m. values obtained from five mice per group. (b) Methacholine-induced increases in airway resistance determined in OVA-sensitised mice challenged with OVA (circles) or saline (triangles) solutions containing either PGE2 (open symbols) or vehicle (closed symbols). In these studies, in vivo lung function was determined 48 h postchallenge. Shown are the mean±s.e.m. values obtained from five to six mice per group.

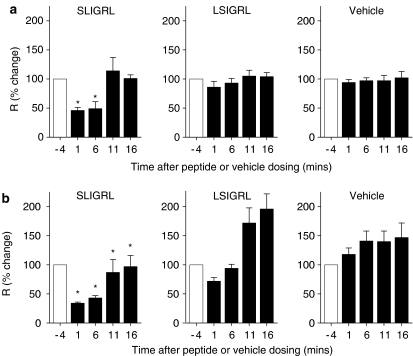

Acute bronchodilator effects of SLIGRL in nonallergic and allergic mice

In vivo administration of SLIGRL, LSIGRL or vehicle (sterile saline) induced no significant change in baseline airway resistance (data not shown). However, SLIGRL caused a transient inhibition of methacholine-induced increases in airways resistance in both nonallergic (Figure 7a) and allergic mice (Figure 7b). For example, in nonallergic mice, SLIGRL inhibited methacholine-induced increases in airway resistance by 54±5% (1 min after dosing) and 51±12% (6 min after dosing) (Figure 7a). These inhibitory effects were significantly greater than those produced by either LSIGRL (14±10 and 7±8%, P<0.05) or vehicle (6±5 and 3±5%, P<0.05). SLIGRL-induced inhibition of methacholine-induced increases in airway resistance was relatively short-lived, with no significant effect evident at either 11 or 16 min after peptide dosing (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Effects of SLIGRL (5 mg kg−1), LSIGRL (5 mg kg−1) and vehicle (10 μl saline) on methacholine-induced increases in airways resistance in (a) nonallergic and (b) allergic mice. Methacholine challenges were assessed 1, 6 and 11 and 16 min after peptide or vehicle dosing. Results were expressed as a percentage of the first methacholine challenge, and presented as mean±s.e.m., n=4–7 mice per group. *Significant differences relative to time-matched LSIGRL responses, P<0.05.

In allergic mice, methacholine-induced increases in airway resistance increased with time in both the vehicle- and LSIGRL-treated control groups (47±26 and 96±26% higher, respectively, at 16 min time point cf. −4 min time point; Figure 7b). Compared to the methacholine-induced responses obtained in either vehicle- or LSIGRL-treated allergic mice, responses in SLIGRL-treated mice were significantly lower at 1, 6, 11 and 16 min after dosing (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA with repeated measures, Figure 7b).

Discussion

An initial objective of the study was to determine the effect of SLIGRL, a PAR2-AP, on the development of airway eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of allergic airways inflammation. In this acute inflammatory model, which was based on a protocol used by Tomkinson et al. (2001), BALB/c mice were sensitised to OVA and subsequently given a single, i.n. challenge of OVA. Examination of the cellular content of BAL fluid recovered from these OVA-sensitised and challenged mice revealed an early, transient increase in neutrophils that peaked at 6 to 12 h. Recent findings indicate that the early neutrophilia in the airways of allergic mice does not play a significant role in the development of later inflammatory changes or airway hyperresponsiveness (Taube et al., 2004). In contrast, a causal relationship between eosinophilia and airways hyperresponsiveness has been demonstrated in several murine models of allergic airway inflammation (Justice et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2003). Consistent with this, the peak increase in eosinophils observed at 48 h postchallenge was associated with concomitant increases in airways responsiveness to methacholine. Moreover, allergic mice treated with i.n. SLIGRL at the same time as OVA challenge had significantly fewer peak numbers of eosinophils and, furthermore, were not hyper-responsive to the bronchoconstrictor agent methacholine.

I.n. administration of SLIGRL, but not a control peptide LSIGRL, inhibited airways eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness within allergic mice. SLIGRL is the tethered ligand sequence for murine PAR2 and its selectivity for PAR2 has been demonstrated in a range of experimental systems. For example, in vivo studies have shown that SLIGRL induces responses in PAR2 (+/+) mice, but is without effect in PAR2 (−/−) mice (Damiano et al., 1999; Seeliger et al., 2003). Furthermore, structure–function studies using immortalised murine cell lines transfected with PARs indicate that SLIGRL selectively activates PAR2, but not other PARs, such as PAR1 (Maryanoff et al., 2001). A partial reverse sequence peptide LSIGRL was used as a control peptide in the current studies because, although it has charge and compositional properties the same as SLIGRL, it lacks PAR2-activating activity (Lan et al., 2000; 2001; 2004; Hollenberg, 2003). In summary, the current findings indicate that SLIGRL-induced stimulation of airway PAR2 activates critical anti-inflammatory pathways in allergic airways, inhibiting the recruitment of eosinophils into the airways and the development of allergic airway pathologies, such as airway hyperresponsiveness. The effect of activators of PAR1 or PAR4 on the development of allergic inflammation is currently unknown.

In many instances, the effects produced by PAR2-APs within the airways are mediated by COX products. For example, bronchorelaxant effects induced by SLIGRL in mouse isolated trachea and bronchi (Cocks et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000) and anaesthetised, ventilated mice (Lan et al., 2004) were abolished in the presence of a dual COX-1/-2 inhibitor indomethacin. Similarly, in the current study, indomethacin significantly blunted SLIGRL-induced inhibition of airways eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness within allergic mice. Thus, the inhibitory effects of PAR2-APs on airway smooth muscle tone and allergic inflammation are each mediated by COX products. Moreover, additional experiments using nimesulide established that the inhibitory effects of SLIGRL on the development of allergic inflammation were mediated by the COX-2 isoform, which has previously been implicated in the bronchorelaxant effects of PAR2-APs (Lan et al., 2000). These findings are consistent with human and animal studies, indicating that COXs play critical roles in regulating airway function and inflammation (for a review see Carey et al., 2003). In summary, these findings clearly demonstrate a critical dependency on COX for SLIGRL-induced inhibition of airway eosinophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness, and indicate a principal role for COX-2 in this process.

COX-derived PGH2 is converted by cell-specific prostaglandin synthases into one of several prostanoids, including PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, PGI2 and thromboxane A2. Most attention has focused on PGE2 because, although it has pleiotropic actions in many tissues, it appears to have a privileged role in limiting the immune-inflammatory response as well as tissue repair processes in the lung (Vancheri et al., 2004). To date, the identity of the prostanoid that mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of SLIGRL has not been unequivocally determined, although several lines of evidence obtained from this study identify PGE2 is a likely candidate. Firstly, exposure of isolated airways obtained from allergic mice to PAR2-AP was associated with a significant, five-fold increase in the generation of PGE2. This is in agreement with an earlier study using tracheal tissue from nonallergic mice, which demonstrated a strong positive relationship between the concentration of SLIGRL and the amount of PGE2 released (Lan et al., 2001). Secondly, i.n. administered PGE2 mimicked the anti-inflammatory effects produced by intranasal SLIGRL, inhibiting airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness. Consistent with these latter findings, allergic rats that received intratracheal PGE2 had reduced numbers of cells expressing IL-4 and IL-5 mRNA, lower numbers of eosinophils and less airway hyperresponsiveness (Martin et al., 2002). Together, these data indicate that the anti-inflammatory effects of SLIGRL were mediated via COX-derived PGE2.

PGE2 acts through four receptors, termed EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4, and the existence of this family of EP receptors coupled to distinct intracellular signalling pathways provides a molecular basis for the diverse physiological actions of PGE2. Of particular interest, it is the EP2 and EP4 receptors, which are coupled to Gs and signal by stimulating adenylate cyclase, that have been implicated in the smooth muscle relaxant (Lan et al., 2000) and anti-inflammatory actions of PGE2. For example, the EP2 receptor has been reported to mediate PGE2-induced inhibition of dendritic cell function (Harizi et al, 2003; Jing et al., 2003) and inhibition of antigen-induced proliferation of lymphocytes (Nataraj et al., 2001). Future studies will need to determine whether the inhibitory effects of SLIGRL on airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness in allergic mice are also mediated by PGE2-induced activation of EP2 receptors.

In the current study, i.n. administration of SLIGRL to OVA-sensitised mice inhibited the development of airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness, indicating that the net effect of PAR2 activation in allergic airways is anti-inflammatory. This contrasts with the findings of Schmidlin et al. (2002) that i.n. SLIGRL did not alter the number of airway eosinophils recovered from the BAL fluid of OVA-sensitised and challenged mice (the effect of SLIGRL on airways hyperresponsiveness was not reported). A key difference between the two studies, and one that may explain the disparate findings, relates to the dose of SLIGRL used. The dose of SLIGRL used by Schmidlin and co-workers and found to be of limited effectiveness (0.165 mg kg−1) was less than 1% of that routinely used in our study (25 mg kg−1). Indeed, the administration of low-dose SLIGRL (0.25 mg kg−1) to allergic mice in the current study did not significantly affect the development of airway eosinophilia or hyperresponsiveness. Significantly, the effective dose of SLIGRL used in our study was the same as that used by Moffatt et al. (2002), who reported that this PAR2-AP inhibited the bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced recruitment of polymorphonuclear leucocytes into the airways of mice. Thus, the effects of SLIGRL are likely to be dose related.

Of particular relevance, Schmidlin et al. (2002) reported that eosinophil infiltration and airways responsiveness to methacholine was diminished in allergic mice lacking PAR2 and was augmented in allergic mice overexpressing PAR2. Thus, these findings indicate that elevated levels of PAR2 expression are associated with worsened airway pathology in allergic mice, and that PAR2 mediates proinflammatory effects (Schmidlin et al., 2002). However, the effects of exogenous activators of PAR2, such as SLIGRL, on allergic inflammatory responses in mice with elevated expression of PAR2 have not been reported, and thus it is unclear what modulatory influences PAR2 stimulants have in these mice. Interestingly, respiratory tract viral infection was associated with elevated epithelial PAR2 expression, and SLIGRL caused enhanced PAR2-mediated bronchodilator function in infected mice (Lan et al., 2004). This raises the intriguing possibility that the elevated expression of PAR2 observed in asthmatic lung (Knight et al., 2001) might also be bronchoprotective.

In the current study, SLIGRL relaxed carbachol-precontracted tracheal preparations and inhibited methacholine-induced increases in airway resistance, confirming our previous findings that this PAR2-AP exhibits bronchodilator activity in nonallergic mice (Lan et al., 2000; 2001; 2004). A recent study indicates that these PAR2-mediated effects involve mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) and p38 MAP kinase, as upstream, nontranscriptional activators of prostanoid production (Kawabata et al., 2004). SLIGRL produced qualitatively similar bronchodilator effects in allergic mice, although its duration of action appeared to be augmented in these mice, compared to the effects produced by LSIGRL or vehicle. The underlying cause for the prolonged action of SLIGRL in allergic mice is not known, although a similar effect has been demonstrated in virus-infected mice that had elevated expression of epithelial PAR2 (Lan et al., 2004). Whether allergic inflammation is associated with increased expression of PAR2 is not known.

In summary, i.n. administration of a PAR2-AP, SLIGRL, inhibited the development of airway eosinophilia and hyperresponsiveness in OVA-sensitised and challenged mice through a COX-dependent pathway, possibly involving COX-2-mediated generation of PGE2. These findings are particularly exciting because they demonstrate for the first time that exogenous substances that activate PAR2 can inhibit several characteristic features of allergic inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the financial assistance from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia and the Western Australian Institute for Medical Research.

Abbreviations

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- LSIGRL

Leu-Ser-Ile-Gly-Arg-Leu-amide

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PAR

protease-activated receptor

- PAR-AP

protease-activated receptor activating peptide

- SLIGRL

Ser-Leu-Ile-Gly-Arg-Leu-amide

References

- CAMERER E., HUANG W., COUGHLIN S.R. Tissue factor- and factor X-dependent activation of protease-activated receptor 2 by factor VIIa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:5255–5260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAREY M.A., GERMOLEC D.R., LANGENBACH R., ZELDIN D.C. Cyclooxygenase enzymes in allergic inflammation and asthma. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2003;69:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(03)00076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOW J.M., MOFFATT J.D., COCKS T.M. Effect of protease-activated receptor (PAR)-1, -2 and -4-activating peptides, thrombin and trypsin in rat isolated airways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1584–1591. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COCKS T.M., FONG B., CHOW J.M., ANDERSON G.P., FRAUMAN A.G., GOLDIE R.G., HENRY P.J., CARR M.J., HAMILTON J.R., MOFFATT J.D. A protective role for protease-activated receptors in the airways. Nature. 1999;398:156–160. doi: 10.1038/18223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMIANO B.P., CHEUNG W.M., SANTULLI R.J., FUNG-LEUNG W.P., NGO K., YE R.D., DARROW A.L., DERIAN C.K., DE GARAVILLA L., ANDRADE-GORDON P. Cardiovascular responses mediated by protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2) and thrombin receptor (PAR-1) are distinguished in mice deficient in PAR-2 or PAR-1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;288:671–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARIZI H., GROSSET C., GUALDE N. Prostaglandin E2 modulates dendritic cell function via EP2 and EP4 receptor subtypes. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2003;73:756–763. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1002483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HE S., WALLS A.F. Human mast cell tryptase: a stimulus of microvascular leakage and mast cell activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1997;328:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)83033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLENBERG M.D. Proteinase-mediated signaling: proteinase-activated receptors (PARs) and much more. Life Sci. 2003;74:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JING H., VASSILIOU E., GANEA D. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits production of the inflammatory chemokines CCL3 and CCL4 in dendritic cells. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2003;74:868–879. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0303116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUSTICE J.P., BORCHERS M.T., CROSBY J.R., HINES E.M., SHEN H.H., OCHKUR S.I., MCGARRY M.P., LEE N.A., LEE J.J. Ablation of eosinophils leads to a reduction of allergen-induced pulmonary pathology. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2003;284:L169–L178. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00260.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KUBO S., ISHIKI T., KAWAO N., SEKIGUCHI F., KURODA R., HOLLENBERG M.D., KANKE T., SAITO N. Proteinase-activated receptor-2-mediated relaxation in mouse tracheal and bronchial smooth muscle: signal transduction mechanisms and distinct agonist sensitivity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;311:402–410. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.068387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAWABATA A., KURODA R., NAKAYA Y., KAWAI K., NISHIKAWA H., KAWAO N. Factor Xa-evoked relaxation in rat aorta: involvement of PAR-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;282:432–435. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KNIGHT D.A., LIM S., SCAFFIDI A.K., ROCHE N., CHUNG K.F., STEWART G.A., THOMPSON P.J. Protease-activated receptors in human airways: upregulation of PAR-2 in respiratory epithelium from patients with asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;108:797–803. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRISHNA M.T., CHAUHAN A., LITTLE L., SAMPSON K., HAWKSWORTH R., MANT T., DJUKANOVIC R., LEE T., HOLGATE S. Inhibition of mast cell tryptase by inhaled APC 366 attenuates allergen-induced late-phase airway obstruction in asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;107:1039–1045. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAN R.S., KNIGHT D.A., STEWART G.A., HENRY P.J. Role of PGE(2) in protease-activated receptor-1, -2 and -4 mediated relaxation in the mouse isolated trachea. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;132:93–100. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAN R.S., STEWART G.A., GOLDIE R.G., HENRY P.J. Altered expression and in vivo lung function of protease-activated receptors during influenza A virus infection in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004;286:L388–L398. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00286.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAN R.S., STEWART G.A., HENRY P.J. Modulation of airway smooth muscle tone by protease activated receptor-1, -2, -3 and -4 in trachea isolated from influenza A virus-infected mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:63–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAN R.S., STEWART G.A., HENRY P.J. Role of protease-activated receptors in airway function: a target for therapeutic intervention. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002;95:239–257. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN J.G., SUZUKI M., MAGHNI K., PANTANO R., RAMOS-BARBON D., IHAKU D., NANTEL F., DENIS D., HAMID Q., POWELL W.S. The immunomodulatory actions of prostaglandin E2 on allergic airway responses in the rat. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3963–3969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARYANOFF B.E., SANTULLI R.J., MCCOMSEY D.F., HOEKSTRA W.J., HOEY K., SMITH C.E., ADDO M., DARROW A.L., ANDRADE-GORDON P. Protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR-2): structure–function study of receptor activation by diverse peptides related to tethered-ligand epitopes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;386:195–204. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIRZA H., SCHMIDT V.A., DERIAN C.K., JESTY J., BAHOU W.F. Mitogenic responses mediated through the proteinase-activated receptor-2 are induced by expressed forms of mast cell alpha- or beta-tryptases. Blood. 1997;90:3914–3922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOFFATT J.D., JEFFREY K.L., COCKS T.M. Protease-activated receptor-2 activating peptide SLIGRL inhibits bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the airways of mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002;26:680–684. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATARAJ C., THOMAS D.W., TILLEY S.L., NGUYEN M.T., MANNON R., KOLLER B.H., COFFMAN T.M. Receptors for prostaglandin E(2) that regulate cellular immune responses in the mouse. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1229–1235. doi: 10.1172/JCI13640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDLIN F., AMADESI S., DABBAGH K., LEWIS D.E., KNOTT P., BUNNETT N.W., GATER P.R., GEPPETTI P., BERTRAND C., STEVENS M.E. Protease-activated receptor 2 mediates eosinophil infiltration and hyperreactivity in allergic inflammation of the airway. J. Immunol. 2002;169:5315–5321. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SEELIGER S., DERIAN C.K., VERGNOLLE N., BUNNETT N.W., NAWROTH R., SCHMELZ M., VON DER WEID P.Y., BUDDENKOTTE J., SUNDERKOTTER C., METZE D., ANDRADE-GORDON P., HARMS E., VESTWEBER D., LUGER T.A., STEINHOFF M. Proinflammatory role of proteinase-activated receptor-2 in humans and mice during cutaneous inflammation in vivo. FASEB J. 2003;17:1871–1885. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1112com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN H.H., OCHKUR S.I., MCGARRY M.P., CROSBY J.R., HINES E.M., BORCHERS M.T., WANG H., BIECHELLE T.L., O'NEILL K.R., ANSAY T.L., COLBERT D.C., CORMIER S.A., JUSTICE J.P., LEE N.A., LEE J.J. A causative relationship exists between eosinophils and the development of allergic pulmonary pathologies in the mouse. J. Immunol. 2003;170:3296–3305. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAUBE C., NICK J.A., SIEGMUND B., DUEZ C., TAKEDA K., RHA Y.H., PARK J.W., JOETHAM A., POCH K., DAKHAMA A., DINARELLO C.A., GELFAND E.W. Inhibition of early airway neutrophilia does not affect development of airway hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2004;30:837–843. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0395OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMKINSON A., CIESLEWICZ G., DUEZ C., LARSON K.A., LEE J.J., GELFAND E.W. Temporal association between airway hyperresponsiveness and airway eosinophilia in ovalbumin-sensitized mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001;163:721–730. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2005010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANCHERI C., MASTRUZZO C., SORTINO M.A., CRIMI N. The lung as a privileged site for the beneficial actions of PGE2. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]