Abstract

Two human breast cancer cell lines, MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, were screened for the presence of functionally significant adenosine receptor subtypes.

MCF-7 cells did not contain adenosine receptors as judged by the lack of an effect of nonselective agonists on adenylyl cyclase activity or intracellular Ca2+ levels. MDA-MB-231 cells showed both a stimulation of adenylyl cyclase and a PLC-dependent increase in intracellular Ca2+ in response to nonselective adenosine receptor agonists.

Both adenosine-mediated responses in MDA-MB-231 cells were observed with the nonselective agonists 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) and 2-(3-hydroxy-3-phenyl)propyn-1-yladenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide (PHPNECA), but no responses were observed with agonists selective for A1, A2A or A3 adenosine receptors. The Ca2+ signal was antagonized by 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) and the nonselective antagonist 9-ethyl-8-furyladenine (ANR 152), but not by A2A or A3 selective compounds.

In radioligand binding with [2-3H](4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol) ([3H]ZM 241385), a specific binding site with a KD value of 87 nM and a Bmax value of 1600 fmol mg−1 membrane protein was identified in membranes from MDA-MB-231 cells.

The pharmacological characteristics provide evidence for the expression of an A2B adenosine receptor in MDA-MB-231 cells, which not only mediates a stimulation of adenylyl cyclase but also couples to a PLC-dependent Ca2+ signal, most likely via Gq/11. The A2B receptor in such cancer cells may serve as a target to control cell growth and proliferation.

The selective expression of high levels of endogenous A2B receptors coupled to two signaling pathways make MDA-MB-231 cells a suitable model for this human adenosine receptor subtype.

Keywords: Adenosine; adenosine receptor; A2B; effector coupling; Ca2+ signal; second messenger; human, cancer; breast cancer

Introduction

Adenosine has dual functions as a metabolite and as a regulator of cellular processes in most organs. The regulatory functions of adenosine are mediated via four subtypes of G protein-coupled receptors which are distinguished as the A1, A2A, A2B and A3 subtypes (Fredholm et al., 2001a). Owing to their widespread occurrence, adenosine receptors have been considered to be important players in pathophysiological situations associated with increased adenosine release and, therefore, are potential targets for drug treatment in numerous dieseases. In addition to asthma (Feoktistov et al., 1998; Spicuzza et al., 2003), cardiovascular diseases (Auchampach & Bolli, 1999; Ganote & Armstrong, 2000; Kitakaze & Hori, 2000) and CNS diseases (Ongini & Fredholm, 1996; Müller, 2000), it was recently also suggested that adenosine receptors may play a role in the regulation of tumor growth (for a review, see Spychala, 2000; Merighi et al., 2003). In particular, A3 receptors have been shown to be present in various tumor cells and are thought to be involved in the control of cell growth and proliferation (Madi et al., 2003, 2004; Fishman et al., 2004). It was also shown that the A3/A1 agonist IB-MECA suppresses human breast cancer cell proliferation through an A3 receptor-independent mechanism (Lu et al., 2003). On the other hand, potential tumor-promoting functions of adenosine were also discussed (Spychala, 2000; Merighi et al., 2003).

The release of adenosine is dependent on the metabolic state of a cell and an increase in energy consumption or hypoxia will lead to an enhanced production of adenosine (Illes et al., 2000; Merighi et al., 2003). It is reasonable to assume, therefore, that metabolically active tumor cells may be characterized by a pronounced adenosine release (Spychala, 2000; Merighi et al., 2003). The local release of adenosine may then regulate the growth and development of these tumor cells in adenosine receptor-dependent and independent ways. Consequently, the presence of defined receptor subtypes will be an important determinant for a specific effect of adenosine on the function of a tumor cell. The knowledge of the expression pattern of different tumor cells is essential, therefore, for the development of potential therapeutic regimens targeting adenosine receptors that may aid in more efficient tumor growth control.

In order to identify adenosine receptor subtypes in an estrogen-positive (MCF-7) and in an estrogen-negative (MDA-MB-231) human breast cancer cell line, we screened these two cell lines for cAMP and Ca2+ signals in response to the nonselective adenosine receptor agonists NECA and PHPNECA. In MCF-7 cells, we did not detect any functional responses suggesting that these cells do not express functionally significant levels of adenosine receptors. In MDA-MB-231, however, we identified a cAMP and a Ca2+ signal with characteristics compatible with the presence of high levels of an A2B adenosine receptor.

Methods

Cell culture

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines were grown adherently and maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1) at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably transfected with human A2B receptors in DMEM/F12 without nucleosides, containing 10% FCS, penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1), L-glutamine (2 mM) at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air and HEK-293 cells stably transfected with human A2B receptors in DMEM containing 10% FCS, penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1), L-glutamine (2 mM) at 37°C in 7% CO2. Cells were split two or three times weekly at a ratio between 1:4 and 1:8. For calcium assays the culture medium was removed, cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized and replated to grow on coverslips precoated with polylysine.

Pertussis toxin treatment of cells was carried out for 24 h using 0.2 μg ml−1 in DMEM containing 0.1% FCS prior to the Ca2+ measurement (Freund et al., 1994).

Membrane preparation

Crude membranes for the measurement of adenylyl cyclase activity and for binding assays were prepared from fresh or frozen cells, respectively, as described recently (Klotz et al., 1998). In brief, cells were homogenized in ice-cold hypotonic buffer (5 mM Tris/HCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and the homogenate was spun for 10 min (4°C) at 1000 × g. The crude membrane fraction was sedimented from the supernatant for 30 min at 100,000 × g. For binding experiments, the membranes were resuspended in 50 mM Tris/HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4, frozen in liquid nitrogen at a protein concentration of 1–3 mg ml−1 and stored at −80°C. For the measurement of adenylyl cyclase activity, crude membranes were prepared with only one centrifugation step. The homogenate from fresh cells was sedimented for 30 min at 54,000 × g and the resulting pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4 for immediate use (Klotz et al., 1998).

Adenylyl cyclase activity

The procedure followed the protocol described previously (Klotz et al., 1998; 1999). Membranes were incubated for 20 min at 37°C in an incubation mixture containing about 150,000 c.p.m. of [α-32P]ATP. The EC50-values for the stimulation of adenylyl cyclase were calculated with the Hill equation. Hill coefficients in all experiments were near unity.

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ and inositol phosphate levels

Concentrations of free intracellular Ca2+ was measured in cells grown to confluency on glass coverslips (10 mm diameter) as described by Abd Alla et al. (1996) with minor modifications. In brief, the cells were washed twice with HBS buffer (composition in mM: NaCl, 150; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 4; MgCl2, 2; glucose, 10; HEPES, 10; pH 7.4), glucose was added before use. For fura-2 loading, cells were incubated in HBS buffer containing 2 μM fura-2/AM and 0.04% (w v−1) of the nonionic detergent pluronic F-127 for 45 min at 37°C. They were washed twice with the buffer and stored in the same buffer at room temperature for another 30 min to allow for complete de-esterification of fura-2/AM. For experiments in the absence of extracelluar Ca2+ cells on coverslips were transferred into HBS buffer containing 0.5 mM EGTA instead of CaCl2. Fluorescence was measured with a Perkin-Elmer LS-50 B spectrofluorometer. The excitation wavelength alternated in intervals of 600 ms between 340 and 380 nm. The slit width was 10 nm, and the emission was measured at 510 nm. The intracellular free calcium concentration is given as the ratio of 340/380 nm. Data for each experiment are normalized to the response observed with 10 μM NECA and are reported as percent of response. The data shown were reproduced in at least three independent experiments performed in duplicates.

Inositol phosphate levels were determined according to the procedure as described by Quitterer et al. (1999) with minor modifications. Cells were loaded with myo-[2-3H]inositol (37 kBq ml−1) for 16 h in inositol-free DMEM supplemented with 0.1% FCS. Before agonist stimulation cells were washed twice with incubation buffer (15 mM HEPES, 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2) and incubated with 10 mM LiCl. Then cells were incubated with NECA for 20 min at 37°C followed by extraction of inositol phsophates as described (Quitterer et al., 1999).

[3H]ZM 241385 binding

The binding of [3H]ZM 241385 was measured in membranes prepared from MDA-MB-231 cells as described above. The incubation mixture contained 80 μg of membrane protein in 50 mM Tris/HCl buffer, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4, 0.2 U ml−1 adenosine deaminase and the indicated concentrations of radioligand, and was incubated at room temperature. After 3 h, the samples were filtered over GF/B glassfiber filters and filter-bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting. The binding data were analyzed by nonlinear curve fitting with the program SCTFIT (De Lean et al., 1982).

Materials

The breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 were provided by the Institut für Zellbiologie ((Tumorforschung), Universitätsklinik Essen, Germany). PENECA and PHPNECA were synthesised by G. Cristalli (Camerino, Italy) and pharmacologically characterized as described recently (Klotz et al., 1999). The nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist 9-ethyl-8-furyladenine (ANR 152) was also synthesised by G. Cristalli (Camerino, Italy). The synthesis and pharmacological characterization will be described elsewhere. Cl-IB-MECA was provided by RBI as part of the NIMH Chemical Synthesis Program. SCH 58261 was kindly provided by P.G. Baraldi (University of Ferrara, Italy). [3H]ZM 241385 and forskolin were from Tocris/Biotrend (Köln, Germany). All other adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists were from Sigma/RBI (Taufkirchen, Germany). Pertussis toxin and thrombin were from Sigma. Fura-2/AM, pluronic F-127, U-73122 and U-73343 were purchased from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Germany), [α-32P]ATP was from Perkin-Elmer LifeScience (Rodgau, Germany) and 8-Br-cAMP was from Biolog (Bremen, Germany). Cell culture media and FCS were purchased from PanSystems (Aidenbach, Germany). Penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1), L-glutamine and G-418 were from Gibco-Life Technologies (Eggenstein, Germany). All other materials were from sources as described earlier (Klotz et al., 1998; 1999).

Results

Two human breast cancer cell lines were screened for functional responses to nonselective adenosine receptor agonists. In MDA-MB-231 cells, both a Ca2+ signal as well as an increase in cAMP was observed in response to 10 μM NECA or PHPNECA. In contrast, no Ca2+ or cAMP signal was detectable in MCF-7 cells (data not shown). Therefore, the following data describe the characterization of adenosine-mediated signals in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells only.

Ca2+ signaling

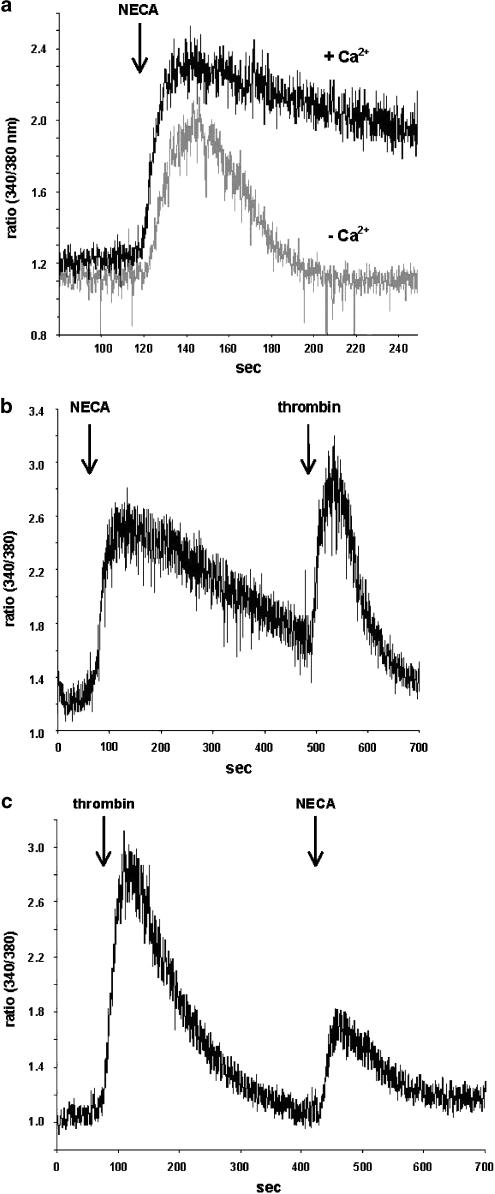

Figure 1a shows that 10 μM NECA caused a transient Ca2+ signal in MDA-MB-231 cells. A Ca2+ signal of almost the same magnitude was observed in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ although the signal was fading at a faster rate (Figure 1a). After an initial NECA response, the cells showed a consecutive response of similar magnitude to 10 nM thrombin (Figure 1b). If cells were stimulated by thrombin first, NECA produced a response that was smaller than a first response to NECA and also smaller than the preceding thrombin signal (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Agonist-mediated Ca2+ signal. (a) MDA-MB-231 cells were stimulated with 10 μM NECA in the presence and absence of extracellular Ca2+. (b) NECA stimulation was followed by 10 nM thrombin. (c) Cells were stimulated with thrombin first followed by NECA. For details see text.

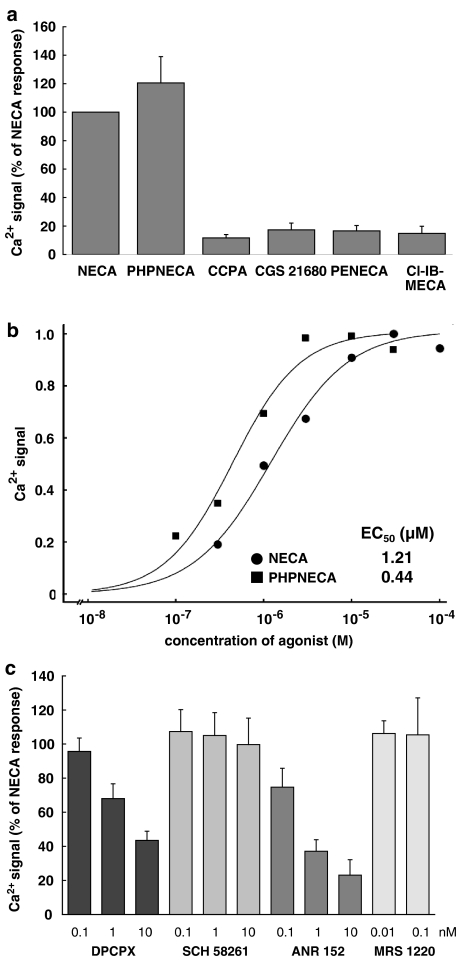

Another nonselective adenosine receptor agonist (PHPNECA, 10 μM) caused a Ca2+ signal similar to NECA (Figure 2a). No response was observed for 10 μM of the A1 selective agonist CCPA (limited selectivity towards A3), CGS 21680 which mainly acts on A2A and to some extent on A1 and A3 receptors (Klotz et al., 1998), and the A3 selective agonists PENECA and Cl-IB-MECA (limited selectivity towards A1) (Klotz et al., 1999). Figure 2b shows the concentration–response curves for NECA and PHPNECA. The EC50 values for these two nonselective agonists were 1250 and 530 nM, respectively (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Pharmacological characteristics of the Ca2+ signal. (a) The nonselective adenosine receptor agonists NECA and PHPNECA caused a similar Ca2+ signal, whereas no response was observed for the subtype selective agonists CCPA, CGS 21680, PENECA and Cl-IB-MECA. The agonist concentration was 10 μM for all compounds. The columns represent means with standard deviation from three experiments performed in duplicate. (b) Concentration–response curves for NECA and PHPNECA. The EC50 values for the experiments shown are 1.2 and 0.44 μM, respectively. (c) The A1/A2B antagonist DPCPX and the nonselective compound ANR 152 antagonized the NECA-induced Ca2+ response in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas the A2A selective compound SCH 58261 and the A3 selective compound MRS 1220 had no effect. Each column represents the means of two experiments with standard deviations.

Table 1.

Functional responses to adenosine receptor agonists in MDA-MB-231 cells

| Adenylyl cyclase | Ca2+ signal | PI-response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NECA | 1130 (1080–1200) | 1250 (890–1760) | 5400 (3020–9700) |

| PHPNECA | 340 (280–400) | 530 (320–890) | n.d. |

EC50-values (nM, with 95% confidence limits in parentheses; n=3) are shown for A2B receptor-mediated stimulation of adenylyl cyclase, Ca2+ signal and PI-response and were determined as described in Methods.

n.d.=not determined.

The NECA response was antagonized in a concentration-dependent manner by the A1/A2B antagonist DPCPX and the nonselective antagonist ANR 152. The subtype selective antagonists SCH 58261 (A2A) and MRS 1220 (A3) had no effect on the NECA-induced Ca2+ signal (Figure 2c).

Activation of adenylyl cyclase

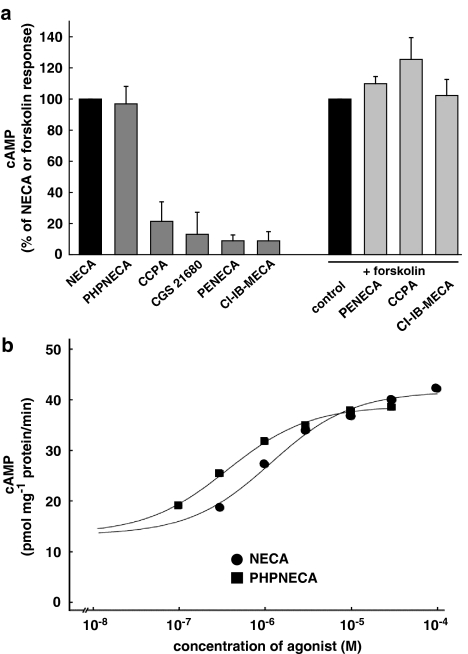

The pharmacological profile of the NECA-induced Ca2+ signal suggested that the response was mediated via the A2B adenosine receptor that normally mediates a stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. Therefore, we tested the effect of the nonselective adenosine receptor agonists NECA and PHPNECA on adenylyl cyclase activity. Both agonists caused a similar increase of cAMP production (Figure 3a). CCPA, CGS 21680, PENECA and Cl-IB-MECA did not cause a cAMP response. As stimulation of A1 and A3 receptors would elicit an inhibitory signal, the effect of respective agonists on forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity was also tested. In Figure 3a it is shown that CCPA, PENECA and Cl-IB-MECA did not inhibit forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase.

Figure 3.

Pharmacological characteristics of the agonist-mediated adenylyl cyclase activation. (a) The nonselective adenosine receptor agonists NECA and PHPNECA caused a similar increase of the activity of adenylyl cyclase, whereas no response was observed for the subtype selective agonists CCPA, CGS 21680, PENECA and Cl-IB-MECA. CCPA, PENECA and Cl-IB-MECA as agonists at the inhibitory receptor subtypes A1 and A3, respectively, did not inhibit adenylyl cyclase activity after stimulation by 10 μM forskolin. The agonist concentration was 10 μM for all compounds. Each column represents the mean of three to four experiments with standard deviations. (b) Concentration–response curves for NECA and PHPNECA. The EC50 values for the experiments shown are 1.2 and 0.36 μM, respectively.

The concentration–response curves in Figure 3b show that NECA and PHPNECA cause an about three-fold increase in adenylyl cyclase activity. The EC50 values for the cyclase stimulation is 1130 and 340 nM for NECA and PHPNECA, respectively (Table 1).

Investigation of the signaling cascade leading to a Ca2+ signal

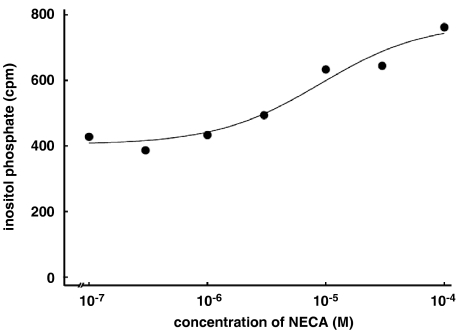

In order to identify the signaling cascade leading to the A2B receptor-mediated Ca2+ response, possible pathways were probed. First, the effect of NECA on production of inositol phosphates was investigated. As shown in Figure 4, NECA caused a concentration-dependent increase of inositol phosphates suggesting a role of phospholipase C for the observed Ca2+ signal. The EC50 value for the increase of inositol phosphates was 5400 nM (Table 1).

Figure 4.

NECA-stimulated accumulation of inositol phosphates. The nonselective adenosine receptor agonist NECA caused a concentration-dependent increase of inositol phosphates. The EC50 value in the single experiment shown here was 5.5 μM.

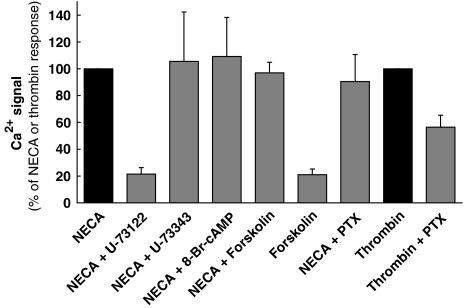

In Figure 5, it is demonstrated that 10 μM of the phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 almost completely blocked the NECA-induced Ca2+ signal whereas the inactive analog U-73343 showed no effect, confirming a role for phospholipase C. Both the cell-permeable cAMP analog 8-Br-cAMP (1 mM) and the adenylyl cyclase stimulator forskolin (10 μM) had no effect on the NECA signal and forskolin caused only a minor Ca2+ signal on its own. Inactivation of Gi with pertussis toxin also did not affect the NECA-induced Ca2+ signal in MDA-MB-231 cells. It did, however, inhibit the thrombin signal by about 50% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Investigation of the signaling cascade leading to intracellular Ca2+ accumulation. The PLC inhibitor U-73122 (10 μM) blocked the NECA-stimulated Ca2+ signal demonstrating that the A2B receptor-mediated effect on intracellular Ca2+ requires PLC. The inactive analog U-73343 (10 μM) showed no effect. Forskolin (10 μM) or 8-Br-cAMP (1 mM) did not modify the NECA effect on Ca2+ levels, forskolin caused only a minor effect on intracellular Ca2+ on its own. Pertussis toxin (PTX, 0.2 μg ml−1 for 24 h) had no effect on the NECA-induced Ca2+ signal while a 50% inhibition of the signal was caused by 10 nM thrombin. The columns represent means with standard deviations of three to four experiments. For further details see text.

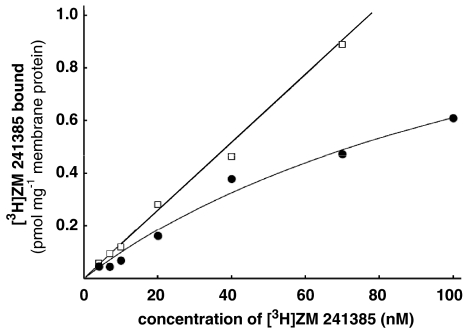

Radioligand binding with [3H]ZM 241385

Although only poor radioligands for A2B adenosine receptors are available with KD values that allow to detect receptors only if expressed at very high level, for example, in stably transfected HEK 293 cells (Ji & Jacobson, 1999; Linden et al., 1999), binding experiments were attempted. As shown in Figure 6, saturable binding of [3H]ZM 241385 was detected suggesting high A2B receptor expression in MDA-MB-231 cells. A KD value of 87 nM and a Bmax value of 1600 fmol mg−1 membrane protein was determined in this cell line (Table 2). The nonspecific binding was fairly high and amounted to about 50–75% at KD value. Specific binding was inhibited by 10 μM of the nonselective antagonist ANR 152 but not by 10 μM of the A2A agonist CGS 21680 (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Saturation binding with [3H]ZM 241385. The graph shows the data from a single experiment with each point measured in triplicate. The KD and Bmax values are 140 nM and 1480 fmol mg−1 membrane protein, respectively. See Table 2 for data in detail.

Table 2.

Saturation experiments with [3H]ZM 241385

| KD (nM)a | Bmax (fmol mg−1 protein)b | |

|---|---|---|

| [3H]ZM 241385 | 87.0 (50.3–150) | 1600 (±243) |

95% confidence limit is in parenthesis.

s.e.m. value is in parenthesis.

Discussion

A3 adenosine receptors have been suggested to play an important role in control of growth and proliferation of tumor cells (Madi et al., 2003; 2004; Fishman et al., 2004). Some studies utilizing IB-MECA provide indirect evidence for the participation of an A3 receptor in the regulation of cell growth and proliferation in human breast cancer cells (Lu et al., 2003; Panjehpour & Karami-Tehrani, 2004). In this study we investigated, therefore, the presence of functionally significant adenosine receptor subtypes in two human breast cancer cell lines. As parameters for functional adenosine-mediated responses, the effects of nonselective agonists on intracellular Ca2+ levels and on the activity of adenylyl cyclase were determined. The estrogen receptor-positive MCF-7 cells did not show any functional response to nonselective adenosine receptor agonists like NECA. On the other hand, the estrogen receptor-negative cell line MDA-MB-231 responded to NECA with an increase in cAMP and a pronounced Ca2+ signal.

The pharmacological characteristics of both the cAMP response and the Ca2+ signal were indicative of the sole presence of an A2B adenosine receptor in MDA-MB-231 cells. This was evidenced by the lack of a stimulatory effect on cAMP levels by the A2A agonist CGS 21680 as well as a lack of an inhibition by A1 or A3 selective agonists like CCPA or PENECA of forskolin-stimulated cyclase activity. An identical activation pattern was observed for the Ca2+ signal indicating that both signals were mediated by the same receptor subtype. The nonselective compounds NECA and PHPNECA were the only agonists that caused a functional response suggesting that they signal via the A2B adenosine receptor. The antagonist profile for the inhibition of the Ca2+ signal clearly confirmed the notion that it was mediated via an A2B subtype.

Although A2B adenosine receptors were pharmacologically distinguished from the A2A subtype over two decades ago (Bruns, 1980) and the human subtype was cloned in 1992 (Pierce et al., 1992), their function is still elusive. One of the problems is that selective ligands are still scarce, and, in particular, no A2B-selective agonists with high potency are known so far. It may well be that high-affinity ligands are hard to find because adenosine exhibits only low affinity for the A2B receptor (Fredholm et al., 2001b). Therefore, physiological levels of adenosine are not sufficient to stimulate this subtype. Even the most potent agonists like PHPNECA exhibit EC50-values at the A2B receptor around 1 μM only, but are more potent at other adenosine receptor subtypes (Klotz et al., 1999). Some A2B-selective antagonists have been reported (Kim et al., 1999; Hayallah et al., 2002; Baraldi et al., 2004); however, they did not reveal more insight into the A2B receptor function as physiological adenosine levels are much too low for a tonic effect to occur that could be blocked by selective antagonists. Consistent with an EC50-value of 420 nM of PHPNECA for the stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity in CHO cells transfected with the human A2B receptor (Klotz et al., 1999), similar potencies were found for the stimulation of adenylyl cyclase activity (EC50 340 nM) and a Ca2+ signal (EC50 530 nM) in MDA-MB-231 cells. Similarly, the NECA potency for cyclase activation (EC50 1130 nM) was in close agreement with previous data with transfected cells from our (EC50 2360 nM; Klotz et al., 1998) and other laboratories (EC50 1230 nM; Alexander et al., 1996).

Further evidence for the existence of an A2B adenosine receptor in MDA-MB-231 cells came from binding studies. We could not detect any specific binding of [3H]CCPA, [3H]NECA or [3H]CGS 21680 (data not shown), but we were able to show specific and saturable binding of [3H]ZM 241385. Although originally introduced as an A2A selective radioligand, it turned out to have significant affinity for the A2B subtype (Ji & Jacobson, 1999). From saturation experiments, we determined a KD-value of 87 nM, which is in agreement with a reported A2B KD-values of 34 nM for this ligand (Ji & Jacobson, 1999). With 1600 fmol mg−1 membrane protein, we found a receptor density for an endogenous A2B adenosine receptor of about one-third of the Bmax value reported for an overexpressing HEK cell line (Ji & Jacobson, 1999). MDA-MB-231 cells seem to be the first cell line expressing an endogenous A2B receptor at levels high enough to be detected in radioligand binding.

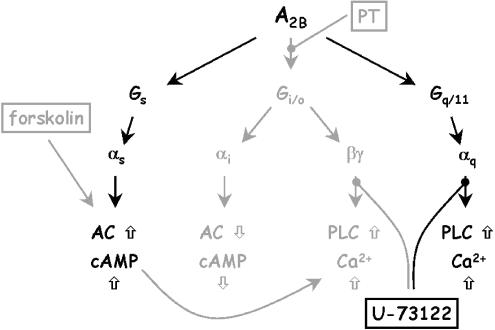

Both A2A and A2B receptors couple to Gs and cause a stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. Although unusual for a stimulatory receptor, reports in the literature suggest that the A2B subtype may also mediate a Ca2+ signal. In CHO cells transfected with the human A2B receptor, we could not detect such a response although the same cells transfected with A3 receptors mediated a Ca2+ response via Gi/o (Englert et al., 2002). For the A2B-mediated Ca2+ responses so far described in the literature, different signaling pathways were suggested. The first report by Feoktistiov et al. (1994) suggests that A2B receptors in human erythroleukemia cells are capable of potentiating a Ca2+ signal elicited by other ligands like thrombin or PGE1 involving Gs. On the other hand, the same group identified an A2B receptor in human mast cells, which was shown to cause a rise of intracellular Ca2+ levels and inositol phosphates in a pertussis toxin-insensitive manner, suggesting a Gq-mediated pathway (Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1995). In Jurkat cells, an A2B receptor-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+ was demonstrated by Mirabet et al. (1997) independent of inositol phosphates. Auchampach et al. (1997) and Gao et al. (1999) found an A2B-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+ in canine mastocytoma cells and HEK-293 cells, respectively, presumably via a Gq-coupled pathway. The A2B-mediated Ca2+ mobilization in human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 in our study was clearly not mediated by an increase in cAMP because forskolin did not mimic the NECA effect on intracellular Ca2+. It was also independent of a pathway via Gi/o and βγ as pertussis toxin did not inhibit the Ca2+ signal. However, inhibition of phospholipase C with the specific inhibitor U-73122 abolished the NECA effect on intracellular Ca2+ levels, suggesting that the signaling pathway in the MDA-MB-231 cells involved Gq/11 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Possible pathways leading to effector activation by A2B adenosine receptors. In MDA-MB-231, both activation of adenylyl cyclase as well as a PLC-mediated increase of intracellular Ca2+ was shown. The Ca2+ signal proceeds most likely via a Gq/11-mediated pathway. Pathways excluded in this study are shown in gray. For further details, see text.

From Figure 1a, it is obvious that activation of the A2B receptor results in both Ca2+ release from intracellular stores as well as Ca2+ influx through plasma membrane channels. Such entry of external Ca2+ is observed in response to receptor-mediated emptying of intracellular stores in many systems and is designated as store-operated Ca2+ entry. It appears that an extended family with various types of store-operated Ca2+ channels is responsible for this type of Ca2+ influx (for review, see Clapham et al., 2003).

A2B adenosine receptors have been identified in several cancerous cell lines (Feoktistov et al., 1994; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1995; Mirabet et al., 1997; Zeng et al., 2003). It is striking that in all these cases, an A2B receptor-mediated Ca2+ signal has been found. Ca2+ is an intracellular signal that is involved in numerous cellular processes including cell differentiation and proliferation, activation of transcription factors, apoptosis and control of malignancy (for review, see Berridge et al., 2000). It is, therefore, conceivable that A2B adenosine receptors do play a role in the control of tumor growth, and development as adenosine levels in solid tumors may reach micromolar levels (Blay et al., 1997) and are thus high enough to stimulate the low-affinity A2B subtype. Both activation of PLC and increasing intracellular Ca2+ levels have been thought to play a role in cell transformation and growth (Berridge et al., 2000) and, consequently, blockade of A2B adenosine receptors may help to control tumor growth. It is interesting to note that the level of the adenosine-producing ecto-5′-nucleotidase was recently shown to be inversely related to estrogen receptor expression (Spychala et al., 2004). These authors concluded that ecto-5′-nucleotidase might serve as a marker for more aggressive estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinoma. Such cells expressing high levels of ecto-5′-nucleotidase would produce the highest levels of adenosine and it may be in these cells that blocking A2B adenosine receptors provides a therapeutic option to control tumor progression. The potential role of Gs-mediated cAMP signaling via A2B receptors in the context of cell transformation and tumor proliferation remains unclear at present.

In summary, we have functionally characterized an endogenous A2B adenosine receptor in the estrogen receptor-negative human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. These cells may serve as a model for native human A2B subtype as they express high receptor levels with functional effector coupling to two different signaling pathways. The A2B receptors mediate a stimulation of adenylyl cyclase, but are in addition coupled to a Ca2+ signal. The Ca2+ response requires activation of phospholipase C and appears to be mediated via Gq/11 pathway. Further work will be required to understand the role of the A2B adenosine receptors in tumor growth and development.

Acknowledgments

The expert technical assistance of Ms Sonja Kachler, Ms Michaela Hoffmann and Mr Nico Falgner is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- ANR 152

9-ethyl-8-furyladenine

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- CGS 21680

2-[p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenylethylamino]adenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide

- Cl-IB-MECA

2-chloro-N6-3-iodobenzyladenosine-5′-N-methyluronamide

- DPCPX

8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- MRS 1220

9-chloro-2-(2-furyl)-5-phenylactylamino[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazoline

- NECA

adenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide

- PENECA

2-phenylethynyladenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide

- PHPNECA

2-(3-hydroxy-3-phenyl)propyn-1-yladenosine-5′-N-ethyluronamide

- SCH 58261

5-amino-7-(2-phenylethyl)-2-(2-furyl)-pyrazolo[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine

- U-73122

1-[6-[[17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl]amino]hexyl]-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione

- U-73343

1-[6-[[17β-3-methoxyestra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17-yl]amino]hexyl]-pyrrolidine-2,5-dione

- [3H]ZM 241385

[2-3H](4-(2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)[1,2,4]triazolo[2,3-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-ylamino]ethyl)phenol)

References

- ABD ALLA S., QUITTERER U., GRIGORIEV S., MAIDHOF A., HAASEMANN M., JARNAGIN K., MÜLLER-ESTERL W. Extracellular domains of the bradykinin B2 receptor involved in ligand binding and agonist sensing defined by anti-peptide antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:1748–1755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALEXANDER S.P.H., COOPER J., SHINE J., HILL S.J. Characterization of the human brain putative A2B adenosine receptor expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO.A2B4) cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:1286–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUCHAMPACH J.A., BOLLI R. Adenosine receptor subtypes in the heart: therapeutic opportunities and challenges. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:H1113–H1116. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUCHAMPACH J.A., JIN X., WAN T.C., CAUGHEY G.H., LINDEN J. Canine mast cell adenosine receptors: cloning and expression of the A3 receptor and evidence that degranulation is mediated by the A2B receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:846–860. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARALDI P.G., TABRIZI M.A., PRETI D., BOVERO A., ROMAGNOLI R., FRUTTAROLO F., ZAID N.A., MOORMAN A.R., VARANI K., GESSI S., MERIGHI S., BOREA P.A. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of new 8-heterocyclic xanthine derivatives as highly potent and selective human A2B adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1434–1447. doi: 10.1021/jm0309654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERRIDGE M.J., LIPP P., BOOTMAN M.D. The versatility and universatility of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLAY J., WHITE T.D., HOSKIN D.W. The extracellular fluid of solid carcinomas contains immunosuppressive concentrations of adenosine. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2602–2605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUNS R.F. Adenosine receptor activation in human fibroblasts: nucleoside agonists and antagonists. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1980;58:673–691. doi: 10.1139/y80-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLAPHAM D.E., MONTELL C., SCHULTZ G., JULIUS D. International union of pharmacology. XLIII. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: transient receptor potential channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003;55:591–596. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.4.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LEAN A., HANCOCK A.A., LEFKOWITZ R.J. Validation and statistical analysis of a computer modeling method for quantitative analysis of radioligand binding data for mixtures of pharmacological receptor subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1982;21:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGLERT M., QUITTERER U., KLOTZ K.-N. Effector coupling of stably transfected human A3 adenosine receptors in CHO cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEOKTISTOV I., BIAGGIONI I. Adenosine A2b receptors evoke interleukin-8 secretion in human mast cells. An enprofylline-sensitive mechanism with implications for asthma. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:1979–1986. doi: 10.1172/JCI118245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEOKTISTOV I., MURRAY J.J., BIAGGIONI I. Positive modulation of intracellular Ca2+ levels by adenosine A2b receptors, prostacyclin, and prostaglandin E1 via a cholera toxin-sensitive mechanism in human erythroleukemia cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:1160–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEOKTISTOV I., POLOSA R., HOLGATE S.T., BIAGGIONI I. Adenosine A2B receptors: a novel therapeutic target in asthma. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FISHMAN P., BAR-YEHUDA S., OHANA G., BARER F., OCHAION A., ERLANGER A., MADI A. An agonist to the A3 adenosine receptor inhibits colon carcinoma growth inmice via modulation of GSK-3β and NF-κB. Oncogene. 2004;23:2465–2471. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., IJZERMAN A.P., KLOTZ K.-N., LINDEN J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001a;53:1–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREDHOLM B.B., IRENIUS E., KULL B., SCHULTE G. Comparison of the potency of adenosine as an agonist at human adenosine receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001b;61:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FREUND S., UNGERER M., LOHSE M.J. A1 adenosine receptors expressed in CHO-cells couple to adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase C. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1994;350:49–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00180010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANOTE C.E., ARMSTRONG S.C. Adenosine and preconditioning in the rat heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000;45:134–140. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO Z., CHEN T., WEBER M.J., LINDEN J. A2B adenosine and P2Y2 receptors stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase in human embryonic kidney-293 cells cross-talk between cyclic AMP and protein kinase C pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:5972–5980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYALLAH A.M., SANDOVAL-RAMÍREZ J., REITH U., SCHOBERT U., PREISS B., SCHUMACHER B., DALY J.W., MÜLLER C.E. 1,8-Disubstituted xanthine derivatives: synthesis of potent A2B-selective adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:1500–1510. doi: 10.1021/jm011049y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILLES P., KLOTZ K.-N., LOHSE M.J. Signaling by extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:295–298. doi: 10.1007/s002100000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JI X., JACOBSON K.A. Use of the triazolotriazine [3H]ZM 241385 as a radioligand at recombinant human A2B adenosine receptors. Drug Des. Discov. 1999;16:217–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM Y.-C., KARTON Y., JI X., MELMAN N., LINDEN J., JACOBSON K.A. Acyl-hydrazide derivatives of a xanthine carboxylic congener (XCC) as selective antagonists at human A2B adenosine receptors. Drug Dev. Res. 1999;47:178–188. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2299(199908)47:4<178::aid-ddr4>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAKAZE M., HORI M. Adenosine therapy: a new approach to chronic heart failure. Expert Opin. Inv. Drug. 2000;9:2519–2535. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.11.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLOTZ K.-N., HESSLING J., HEGLER J., OWMAN C., KULL B., FREDHOLM B.B., LOHSE M.J. Comparative pharmacology of human adenosine receptor subtypes – characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1998;357:1–9. doi: 10.1007/pl00005131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLOTZ K.-N., CAMAIONI E., VOLPINI R., KACHLER S., VITTORI S., CRISTALLI G. 2-Substituted N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine derivatives as high-affinity agonists at human A3 adenosine receptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1999;360:103–108. doi: 10.1007/s002109900044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDEN J., THAI T., FIGLER H., JIN X., ROBEVA A.S. Characterization of human A2B adenosine receptors: radioligand binding, western blotting, and coupling to Gq in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and HMC-1 mast cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LU J., PIERRON A., RAVID K. An adenosine analogue, IB-MECA, down-regulates estrogen receptor α and supresses human breast cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6413–6423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADI A., BAR-YEHUDA S., BARER F., ARDON E., OCHAION A., FISHMAN P. A3 adenosine receptor activatoin in melanoma cells. Association between receptor fate and tumor growth inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:42121–42130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADI A., OCHAION A., RATH-WOLFSON L., BAR-YEHUDA S., ERLANGER A., OHANA G., HARISH A., MERIMSKI O., BARER F., FISHMAN P. The A3 adenosine receptor is highly expressed in tumor versus normal cells: potential target for tumor growth inhibition. Clin. Canc. Res. 2004;10:4472–4479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERIGHI S., MIRANDOLA P., VARANI K., GESSI S., LEUNG E., BARALDI P.G., TABRIZI M.A., BOREA P.A. A glance at adenosine receptors: novel target for antitumor therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;100:31–48. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIRABET M., MALLOL J., LLUIS C., FRANCO R. Calcium mobilization in Jurkat cells via A2b adenosine receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÜLLER C.E. A2A adenosine receptor antagonists – future drugs for Parkinson's disease. Drugs Future. 2000;25:1043–1052. [Google Scholar]

- ONGINI E., FREDHOLM B.B. Pharmacology of adenosine A2A receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996;17:364–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANJEHPOUR M., KARAMI-TEHRANI F. An adenosine analog (IB-MECA) inhibits anchorage-dependent cell growth of various human breat cancer cell lines. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;36:1502–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PIERCE K.D., FURLONG T.J., SELBIE L.-A., SHINE J. Molecular cloning and expression of an adenosine A2b receptor from human brain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;187:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUITTERER U., ZAKI E., ABD ALLA S. Investigation of the extracellular accessibility of the connecting loop between membrane domains I and II of the bradkinin B2 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:14773–14778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPICUZZA L., BONFIGLIO C., POLOSA R. Research applications and implications of adenosine in diseased airways. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:409–413. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPYCHALA J. Tumor-promoting functions of adenosine. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;87:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00053-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPYCHALA J., LAZAROWSKI E., OSTAPKOWIECZ A., AYSCUE L.H., JIN A., MITCHELL B.S. Role of estrogen receptor in the regulation of ecto-5′-nucleotidase and adenosine in breast cancer. Clin. Canc. Res. 2004;10:708–717. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0811-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZENG D., MAA T., WANG U., FEOKTISTOV I., BIAGGIONI I., BELARDINELLI L. Expression and function of A2B adensoine receptors in the U87MG tumor cells. Drug Dev. Res. 2003;58:405–411. [Google Scholar]