Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether purines exerted a physiological role in central cardiovascular modulation at the level of the locus coeruleus (LC).

In pentobarbitone-anaesthetised Wistar–Kyoto rats, unilateral microinjection of ATP or α,β-methyleneATP into the LC elicited dose-related decreases in blood pressure and heart rate. Unilateral microinjection of the P2 purinoceptor antagonists suramin and PPADS, caused pressor and tachycardic responses. Administration of the selective P2X1 receptor antagonist NF-279 had no effect. While both ATP and L-glutamate (L-GLU) resulted in depressor responses after intra-LC microinjection, following intra-LC microinjection of P2 purinoceptor antagonists into the LC, the effects of subsequent administration of either ATP or L-GLU were functionally reversed, such that a pressor response ensued.

Microinjection of noradrenaline into the LC caused an increase in blood pressure and heart rate; however, the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist idazoxan had no cardiovascular effects, but did prevent the pressor response to PPADS or suramin. In addition, coinjection of idazoxan with either suramin or PPADS abolished the ATP and L-GLU mediated pressor responses observed following either suramin or PPADS administration.

The present data suggest that firstly, purines are capable of acting within the LC to ultimately modulate the cardiovascular system and secondly, that there is apparently a functional interaction between tonically active purinergic and noradrenergic systems within the LC of the rat.

Keywords: Locus coeruleus, P2X receptors, autonomic nervous system, microinjection, blood pressure, PPADS, suramin, noradrenaline

Introduction

The locus coeruleus (LC) constitutes the largest collection of noradrenergic cells within the mammalian central nervous system, with widespread connections innervating all levels of the neuraxis (Foote et al., 1983; Aston-Jones et al., 1986). Consequently, the LC is implicated in the control of many homeostatic functions including the maintenance of attention, motivation, arousal states (Svensson & Thorén, 1979; Bhaskaran & Freed, 1988), sleep (Aston-Jones & Bloom, 1981), and cardiovascular function (Sved & Felsten, 1987; Miyawaki et al., 1993; Murase et al., 1993). Indirect evidence to support a role for the LC in central cardiovascular control can be derived from a number of findings; firstly, the LC receives a major input from the rostral ventrolateral medulla, a region containing presympathetic motoneurones; although those that project to the LC do not appear to be the spinally projecting cells (Aston-Jones et al., 1986). The LC may, however, receive input from rostral ventrolateral medulla neurones that are activated by either hypotension and/or hypovolaemia, which may explain the responsiveness of LC neurones to these haemodynamic changes. Secondly, the firing frequency of LC neurones are altered by changes in blood volume, blood pressure (BP) and stimulation of baroreceptor afferent fibres (Olpe et al., 1985). Finally, noradrenaline (NA) turnover is affected by changes in baroreceptor activity (Singewald & Philippu, 1993).

The first direct evidence to support a role for the LC in central cardiovascular control was obtained when microinjection of L-glutamate (L-GLU) into the LC resulted in a depressor and bradycardic response in chloralose anaesthetised rats (Sved & Felsten, 1987). Furthermore, in the anaesthetised rat, this response appears to be mediated, at least in part, by a decrease in sympathetic outflow to various vascular beds, and thus a reduction in total peripheral resistance (Miyawaki et al., 1993). Microinjection of other agonist compounds such as D,L-homocysteic acid (Murase et al., 1993) and the precursor of nitric oxide, L-arginine (Yao et al., 1999), have also been shown to elicit decreases in BP and heart rate (HR), while the application of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors fail to elicit notable cardiovascular responses in pentobarbitone anaesthetised rats (Yao et al., 1999). These results suggest that while the LC may centrally modulate the cardiovascular system, it does not appear to play a tonic role in central cardiovascular regulation.

A number of other neurotransmitters have also been shown to modulate the activity of LC neurones such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (Aston-Jones et al., 1991), vasopressin (Berecek et al., 1987) and NA (Dahlof et al., 1981). More recently, adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) has also been shown to elicit changes in the firing of LC neurones (Harms et al., 1992; Tschopl et al., 1992; Illes et al., 1994; Scheibler et al., 2004). ATP mediates physiological actions via the activation of P2 purinoceptors (Burnstock, 1997), which have been divided into two major classes based on structural and functional differences. P2Y receptors are G-protein coupled receptors, while P2X receptors are ligand-gated ion channels whereby activation results in membrane depolarisation and a voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx (Mateo et al., 1998). In whole-cell recordings made in brain slices containing the LC, both α,β-methyleneATP (α,β-meATP) and ATP were found to cause an inward current via the activation of both P2X (Tschopl et al., 1992) and P2Y receptors (Shen & North, 1993). Thus, it appears that ATP has the potential of being utilised as a neurotransmitter or neuromodulator from neurones terminating within the LC or as a cotransmitter from recurrent axonal collaterals/dendrites of intrinsic LC neurones (Nieber et al., 1997) to activate P2 purinoceptors. It is also possible, however, that purines may be released from glia or blood vessels and subsequently modulate neuronal activity. While much information has been gained from whole-cell recordings in brain slice preparations, the physiological effects of ATP in the LC in vivo are still unknown. In light of this, the aims of the present study were to determine the role of purines in cardiovascular modulation at the level of the LC.

Methods

All experiments described herein were performed in accordance with the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986, under the guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Experimental Purposes in Australia.

General methods

All experiments were performed on male adult Wistar–Kyoto rats (Biological Research Laboratory, Austin Hospital, Australia). The animals were housed in a temperature and humidity controlled environment on a 12-h light–dark cycle. Rats (300–380 g; n=66) were anaesthetised with sodium pentobarbitone (60 mg kg−1 i.p.) and placed on a heating mat prior to surgery. Anaesthesia was maintained throughout the remainder of the experiment with supplementary injections of sodium pentobarbitone (10–20 mg kg−1 i.v.) as required. The depth of anaesthesia was monitored regularly and deemed to be adequate when, a paw pinch resulted in the absence of a withdrawal response, the blink reflex was absent, and arterial pressure was stable. The rats were not artificially ventilated and allowed to spontaneously breathe room air for the entirety of the experiment. The femoral artery was cannulated and arterial pressure was monitored via a pressure transducer (Gould P23ID, U.S.A.). HR was determined using a tachometer (Grass, model 7P4F) triggered by the arterial pressure pulses. BP and HR were recorded continuously on a polygraph (Grass model 79D, Grass Instruments, U.S.A.). Rats were then placed in a stereotaxic head frame (David Kopf Instruments, U.S.A.) with the incisor bar set at −3.3 mm below the interaural point. The skin overlying the skull was reflected back, and a 3-mm burr hole was drilled in the occipital bone overlying the right LC (AP −9.7 mm; ML −1.3 mm from bregma) according to coordinates derived from the atlas of Paxinos & Watson (1986).

Multiunit recordings

Multiunit recordings of LC neurones were performed as described previously (Yao et al., 1999). Briefly, multiunit neuronal activity was recorded via a platinum electrode inserted in the central barrel of a five-barrelled glass micropipette (3 M KCl bridge; 1–2.5 MΩ impedance). The signal was received through a head stage (AI 405, Axon Instruments Inc.) prior to being amplified (Cyberamp 320, Axon Instruments Inc.). The output was continuously monitored by an audio monitor while also being displayed on a personal computer running a data acquisition program (Axoscope v1.1.1, Axon Instruments Inc.). The electrophysiological recordings were used as a tool to accurately target the LC. The LC was identified by a spontaneous discharge frequency of 0.5–5 Hz, and an increase in firing in response to noxious stimuli as previously described (Cedarbaum & Aghajanian, 1976). Other criteria used in the location of the LC included the location of the mesencephalic nucleus of the trigeminal nerve, whereby a burst of multiunit activity is observed in response to lowering of the mandible and a reduction in multiunit activity when the electrode was situated in the fourth ventricle.

Microinjection procedures

For the microinjection studies, five-barrelled micropipettes with a combined tip diameter of no greater than 30 μm were employed. The calibrated pipettes were filled with various compounds to be tested, all of which were dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF, pH 7.4; 125 mM NaCl, 27 mM NaHCO3, 2.5 mM KCl, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM Na2SO4, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM CaCl2). Drug microinjections into the LC were performed by applying pressure pulses of 400–600 ms duration with the use of a multichannel pneumatic pressure injector (Picospritzer™ II, General Valve Corporation, U.S.A.) connected to a nitrogen gas cylinder. The injection volume was measured by observing the movement of the meniscus in the pipette through a microscope with a graticule in the eyepiece. All injections were made in 40 nl volumes and a maximum of five injections were made in any individual rat. Once an ATP or L-GLU depressor site had been identified, the multibarrel micropipette was not moved for the entirety of the experiment. The drugs and the amounts of each drug used were selected on the basis of previous microinjection studies (Ergene et al., 1994; Abrahams et al., 1996) and pilot studies established the pharmacological relevance of these doses within the rat LC. These included ATP (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 nmol), α,β-meATP (0.25, 0.5 and 0.75 nmol), L-GLU (2.0 nmol), NA (0.25 nmol), suramin (1.0 nmol), pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulphonic acid (PPADS; 0.5 nmol), 8,8′-[carbonylbis(imino-4,1-phenylenecarbonylimino-4,1-phenylenecarbonylimino)]bis-1,3,5-naphthalenetrisulphonic acid hexasodium (NF-279; 0.75 nmol), idazoxan (IDA; 5 nmol).

Histological analysis of injection sites

At the conclusion of each experiment, the rat was decapitated, the brain removed, frozen over liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until sectioned. The brains were sectioned (14 μm) on a cryostat (Leica Cryocut 1800). Sections were histologically processed (0.5% neutral red) and injection sites identified as the end of the pipette tract under a light microscope (Olympus BH2).

Data analysis

After each microinjection, BP and HR were measured at the point of maximum deviation from baseline values. Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) was calculated as: MAP= diastolic pressure+1/3 (systolic pressure−diastolic pressure). MAP and HR are expressed in mmHg and beats per minute (b.p.m.) respectively. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m unless otherwise stated. All data passed normality and equal variance tests and analysed by either a one-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test (dose–response) or an unpaired Student's t-test. Data were considered significant when P<0.05.

Materials

The following drugs and chemicals were used: ATP (Sigma, MO, U.S.A.), α,β-meATP (Sigma, U.S.A.), L-GLU (Sigma, U.S.A.), NA (Sigma, U.S.A.), suramin hexasodium salt (Tocris Cookson Ltd, U.K.), PPADS; Tocris Cookson Ltd, U.K.), NF-279 (Tocris Cookson Ltd, U.K.), idazoxan (IDA; K&K laboratories, U.K.). All other reagents used were of laboratory or analytical grade obtained from various suppliers.

Results

Effects of ATP and α,β-meATP in the LC

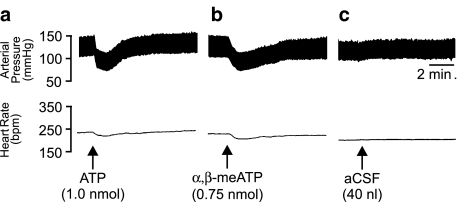

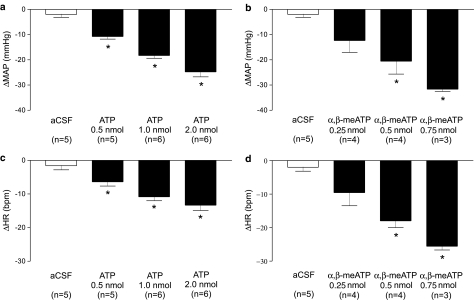

To determine the cardiovascular effects of stimulating P2 purinoceptors in the LC of the anaesthetised rat, microinjections of both ATP and α,β-meATP were performed (Figure 1a, b). Unilateral microinjection of ATP (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 nmol in 40 nl) into the LC of the anaesthetised rat (n=5–6) elicited a significant (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) dose-related decrease in MAP (Figure 2a), accompanied by a corresponding decrease in HR (Figure 2b). Both the depressor and bradycardic effects were rapid in onset whereby a maximum effect was reached within 20 s of the injection. Furthermore, the responses to ATP were readily reproducible, as subsequent injections elicited similar responses to those observed after the initial injection. Control microinjections of aCSF into the same site (Figure 1c), or ATP in the areas surrounding the LC produced no observable alterations to either MAP or HR except when ATP was injected into areas adjacent to or including the parabrachial region where pressor responses were observed. In addition to ATP, the effects of the enzymatically stable analogue of ATP, α,β-meATP, was also investigated. α,β-MeATP (0.25, 0.5 and 0.75 nmol in 40 nl), in a similar manner to that seen with ATP, elicited a significant (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) dose-related depressor (Figure 2c) and bradycardic response (Figure 2d). The responses to α,β-meATP also had a rapid onset with the maximum response being reached within 20 s after the injection. Furthermore, responses to α,β-meATP were reproducible and not subject to desensitisation under the conditions employed as a repeated injection of α,β-meATP moments after the initial injection yielded comparable cardiovascular responses. These findings are supported by electrophysiological data showing little if any desensitisation to repeated exposure of LC neurones in patch-clamp recordings of brain slice preparations to α,β-meATP (Shen & North, 1993; Scheibler et al., 2004). Control injections of α,β-meATP outside the LC, however, resulted in either no response or occasionally a pressor response (range 5–20 mmHg; n=4, see Figure 10).

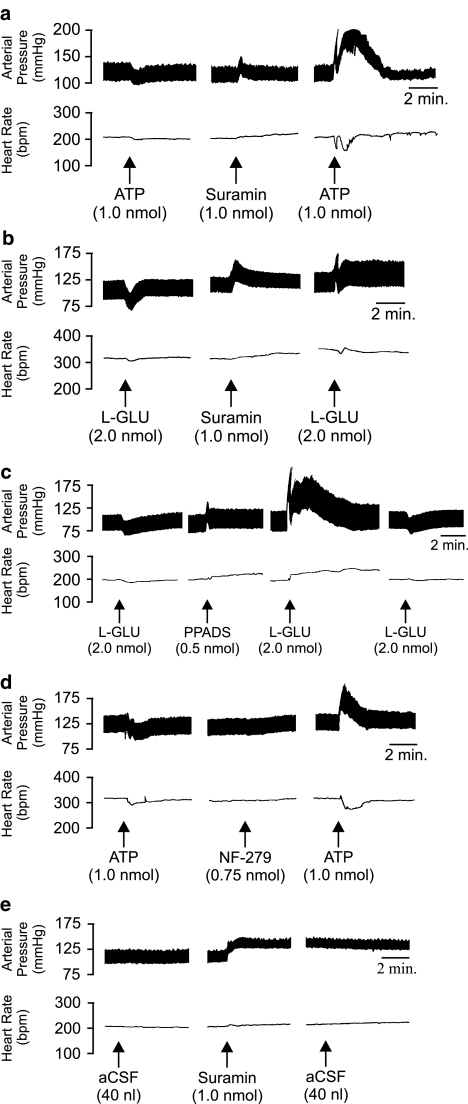

Figure 1.

Representative polygraph chart recorder traces showing the arterial BP (mmHg) and HR (b.p.m.) effects of (a) ATP; (b) α,β-meATP and (c) aCSF microinjected into the locus coeruleus of anaesthetised rats. The arrows indicate the time of injection.

Figure 2.

Bar graphs showing the BP (a, c) and HR (b, d) effects of increasing doses of ATP and αβ-meATP respectively, when microinjected into the LC of anaesthetised (sodium pentobarbitone 60 mg kg−1 i.p.) rats. Values are expressed as peak changes from basal MAP and HR. Each point represents the mean response of three to six rats±s.e.m. *P<0.05 compared to aCSF control injections, one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni's post hoc test.

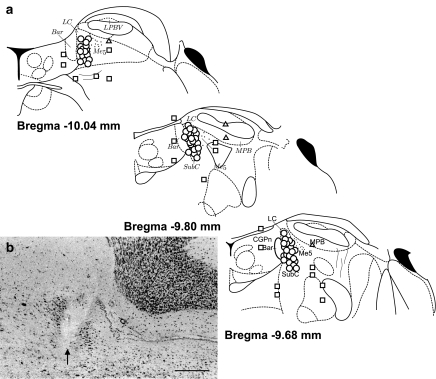

Figure 10.

Microinjection sites in the LC for all experiments. (a) Schematic diagram of coronal sections of the pons at the level of the LC modified from the atlas of Paxinos & Watson (1986), showing the locations of injection sites where ATP or L-GLU elicited depressor responses (circles), no response (squares) or pressor responses (triangles). The circles, squares and triangles represent the position of the micropipette tip. (b) Representative photomicrograph of an injection site within the LC. The arrow marks the position of the pipette tip. The scale bar represents 300 μm. Bar, Barrington's nucleus; CGPn, central pontine grey; LC, locus coeruleus; Me5, mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus; MPB, medial parabrachial nucleus; SubC, nucleus subcoeruleus.

Effect of P2 purinoceptor antagonists in the LC

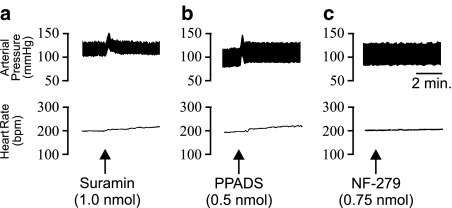

In order to elucidate whether there was ongoing release of purines within the LC capable of influencing BP and HR, a number of P2 purinoceptor antagonists were investigated. Unilateral microinjection of the nonselective P2 purinoceptor antagonist suramin (1.0 nmol) into the rat LC evoked a significant (P<0.05, unpaired Student's t-test compared to aCSF injecitons) rapid and sustained pressor (+22.9± 4.1 mmHg) and tachycardic response (+17.8±2.9 b.p.m.) (Figure 3a; n=6). Similarly, microinjection of the more selective P2X receptor antagonist, PPADS (0.5 nmol), also elicited a similar response whereby a significant (P<0.05, unpaired Student's t-test) increase in BP (+14.9±3.9 mmHg) and HR (+21.0±6.9 b.p.m.) was observed (Figure 3b; n=6). However, in contrast to the response observed with suramin, the pressor response evoked by PPADS was transient and returned to baseline values within approximately 30 s. Administration of the selective P2X1 receptor antagonist NF-279 (0.5 and 0.75 nmol) failed to elicit any observable cardiovascular responses (Figure 3c; n=5).

Figure 3.

Representative polygraph chart recorder traces showing the arterial BP (mmHg) and HR (b.p.m.) effects of (a) Suramin; (b) PPADS and (c) NF-279 microinjected into the locus coeruleus of anaesthetised rats. The arrows indicate the time of injection.

Effect of P2 purinoceptor antagonists on the responses to ATP and glutamate

The effects of ATP were also tested subsequent to treatment with P2 purinoceptor antagonists. Pressure application of ATP (1.0 nmol) 10 min following administration of suramin (1.0 nmol; intra-LC) resulted in a significant (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) biphasic pressor and bradycardic response (−12.6±18.3 b.p.m. phase 1; −14.8±9.3 b.p.m. phase 2; n=5). The first phase of the hypertension was characterised by a rapid increase in pressure (+41.7±8.9 mmHg) followed by a recovery to baseline values after approximately 10–30 s, while the second phase of the pressor response developed more slowly and consisted of a sustained rise in pressure (+53.2±11.8 mmHg), which lasted approximately 3–8 min (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Representative polygraph chart recorder trace of phasic arterial pressure and HR following unilateral microinjection of various compounds into the LC of anaesthetised WKY rats. (a) ATP and suramin: note that following application of suramin, the effects of ATP were reversed, whereby a depressor response was converted to a pressor response. (b) L-GLU and suramin: note that following application of suramin the effects of L-GLU were reversed, whereby a depressor response was converted to a pressor response. (c) L-GLU and PPADS: following the application of PPADS the cardiovascular effects of L-GLU were reversed, whereby a depressor response was converted to a pressor and tachycardic response. (d) ATP and NF-279: note once again that following application of NF-279 the effects of ATP were reversed, whereby a depressor response was converted to a pressor response. (e) aCSF and suramin: following the application of suramin, the administration of aCSF had no observable cardiovascular effects. The arrows indicate the time at which the injections were made.

In an attempt to elucidate possible interactions between the glutamatergic and purinergic systems within the LC, the above sequence of experiments was repeated using L-GLU. Like the responses described above, microinjection of L-GLU (2.0 nmol) 10 min postsuramin application resulted in a significant (P<0.05; one-way ANOVA) biphasic (+28.9±11.7 mmHg phase 1; +9.7±4.6 mmHg phase 2) pressor and monophasic bradycardic (−10.6±4.3 b.p.m., n=5) response (Figure 4b). Owing to the limitations of suramin as a P2X purinoceptor antagonist, experiments were also performed with PPADS, a more selective antagonist at P2X purinoceptors (Lambrecht et al., 1992; McLaren et al., 1994). PPADS (0.5 nmol) was also found to reverse the effects of L-GLU injections in the LC (n=5) in a manner similar to suramin. The pressor responses were characterised by a significant (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA) biphasic increase in BP (+49.4±14.2 mmHg phase 1; +47.7±13.6 mmHg phase 2). However, in contrast to the suramin experiments, a tachycardia (+30.0±11.7 b.p.m.) rather than a bradycardia was observed accompanying the L-GLU pressor response (Figure 4c). A repeat injection of L-GLU 1-h after the PPADS treatment yielded a depressor/bradycardic response similar to the initial response prior to antagonist, suggesting a full recovery.

Cardiovascular responses to ATP were also tested in the presence of the selective P2X1 receptor antagonist NF-279. Microinjection of ATP (1.0 nmol) 10 min subsequent to the application of NF-279 (0.75 nmol) was also found to cause a reversal of the ATP response whereby a depressor response was converted to a significant (P<0.05, paired Student's t-test) pressor (+45±5.5 mmHg) response. This pressor response was accompanied by a bradycardia (−38±6.7 b.p.m.). While the increase in BP was rapid (similar kinetics to those observed following PPADS), this response was only monophasic. BP and HR returned to baseline levels after approximately 4 min (Figure 4d; n=4). Control microinjections of aCSF before and after P2-purinoceptor antagonist administration had no effects on basal BP or HR (Figure 4e; n=4).

Another series of rats were utilised to determine whether the effects of ATP on BP and HR following P2X receptor blockade were due to catabolism of ATP to adenosine. Intra-LC microinjection of adenosine (0.5 nmol) into L-GLU depressor sites had no effect on BP or HR. Microinjection of adenosine had no effects on subsequent application of L-GLU (data not shown).

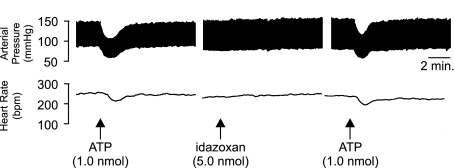

Effect of α2-adrenoceptor agonism and antagonism in the LC

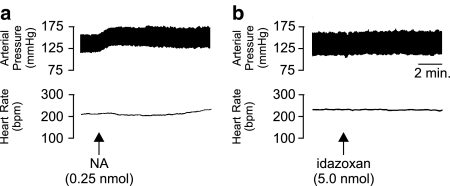

Unilateral microinjection of NA (0.25 nmol) caused a significant (P<0.05, unpaired Student's t-test compared to aCSF injections) slowly developing pressor response (+10.4±2.7 mmHg) accompanied by a slight (but not significant) increase in HR (+5.4±1.3 b.p.m.; n=4; Figure 5a). Microinjection of idazoxan (5.0 nmol) into the LC did not produce any significant changes in BP or HR alone (Figure 5b). Moreover, idazoxan was found to have little effect on the depressor and bradycardic responses to subsequent application of ATP (10 min postidazoxan; Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Representative polygraph chart recorder traces of phasic arterial pressure and HR following unilateral microinjection of (a) noradrenaline (NA) and (b) idazoxan into the LC of anaesthetised (sodium pentobarbitone, 60 mg kg−1 i.p.) WKY rats. The arrows indicate the time at which the injections were made.

Figure 6.

Representative polygraph chart recorder trace of phasic arterial pressure and HR following unilateral microinjection of ATP followed by idazoxan followed by a repeat injection of ATP (10 min after idazoxan) into the LC of anaesthetised (sodium pentobarbitone, 60 mg kp−1 i.p.) WKY rats. The arrows indicate the time at which the injections were made.

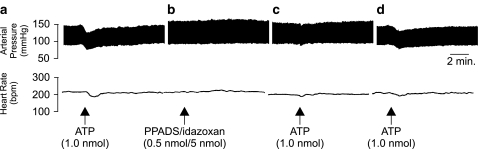

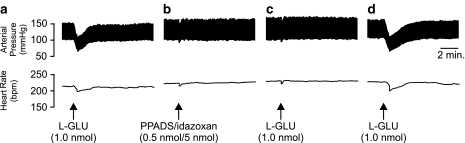

In order to determine whether the pressor responses elicited by ATP following P2-purinoceptor blockade were mediated by NA acting via α2-adrenoceptors, the effects of an antagonist mixture of idazoxan and PPADS (5 nmol/0.5 nmol mix, respectively) were investigated. Prior to administration of the antagonist mixture, the effects of ATP alone were confirmed. ATP was found to produce the characteristic depressor (−24±3.4 mmHg) and bradycardic (−24±4.3 b.p.m.) responses (Figure 7a). Subsequent application of idazoxan/PPADS 30 min following the application of ATP produced no significant responses, indicating that the inclusion of idazoxan abolished the pressor response elicited by PPADS when applied alone (Figure 7b). Microinjection of ATP 10 min following the administration of the antagonist cocktail significantly (P<0.05, paired Student's t-test) attenuated a subsequent cardiovascular response to ATP (Figure 7c). Recovery of the ATP response was observed 1 h after administering the idazoxan/PPADS mix (Figure 7d).

Figure 7.

Representative polygraph chart recorder trace of phasic arterial pressure and HR following unilateral microinjection of (a) ATP, (b) PPADS/idazoxan antagonist mixture, (c) ATP 10 min after the PPADS/idazoxan microinjection, and (d) ATP 1 h after the PPADS/idazoxan microinjection into the LC of anaesthetised (sodium pentobarbitone, 60 mg kg−1 i.p.) WKY rats. Note that the pressor response observed following P2-purinoceptor blockade is abolished by the coadministration of idazoxan. The arrows indicate the time at which the injections were made.

Parallel observations were also made in the case of L-GLU. The initial microinjection of L-GLU resulted in a significant (P<0.05, unpaired Student's t-test compared to aCSF injections) depressor (31±2.3 mmHg) and bradycardic response (33±3.1 b.p.m., n=5) (Figure 8a). Microinjection of idazoxan/PPADS 30 min following L-GLU had no significant effects on BP and HR (Figure 8b). As with the case of the ATP experiments described above, the idazoxan/PPADS antagonist mixture significantly (P<0.05, paired Student's t-test) attenuated the response to L-GLU administration (Figure 8c). In addition, full recovery of the L-GLU depressor and bradycardic response was observed 1 h after the application of the idazoxan/PPADS mix (Figure 8d).

Figure 8.

Representative polygraph chart recorder trace of phasic arterial pressure and HR following unilateral microinjection of (a) L-GLU, (b) PPADS/idazoxan antagonist mixture, (c) L-GLU 10 min after the PPADS/idazoxan microinjection, and (d) L-GLU 1 h after the PPADS/idazoxan microinjection into the LC of anaesthetised (sodium pentobarbitone, 60 mg kg−1 i.p.) WKY rats. Note that the L-GLU mediated pressor response observed following P2-purinoceptor blockade is abolished by the coadministration of idazoxan. The arrows indicate the time at which the injections were made.

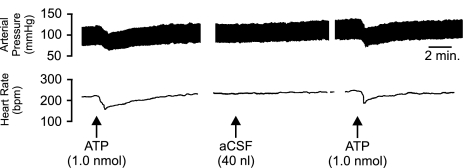

In order to control for volume or trauma effects caused by repeated injections, aCSF was administered in place of the idazoxan/PPADS mix (Figure 9). Following the initial injection of ATP; where a depressor (−20.3±3.4 mmHg) and bradycardic (−11.8±2.3 b.p.m.) response was observed; application of aCSF (40 nl) failed to produce any observable changes in BP or HR. Subsequent microinjection of ATP 10 min following the application of aCSF was unaffected and as such a depressor and bradycardic response was observed (n=4).

Figure 9.

Representative polygraph chart recorder trace of phasic arterial pressure and HR following unilateral microinjection of ATP followed by aCSF followed by a repeat injection of ATP (10 min after aCSF) into the LC of anaesthetised (sodium pentobarbitone, 60 mg kp−1 i.p.) WKY rats. The arrows indicate the time at which the injections were made.

All injection sites were found to be within the borders of the LC as defined by the atlas of Paxinos & Watson (1986). Control microinjections outside of the LC yielded no response, except for α,β-meATP where occasional pressor responses were observed following injections outside of the LC. Figure 10 shows a schematic diagram of all the injections made within the LC (circles), in addition to the control injections made outside of the LC (squares, triangles).

Discussion

There is growing evidence that clearly demonstrates that ATP and its synthetic analogues can excite LC neurones and hence suggest a role for ATP neurotransmission within the LC of the rat (Tschopl et al., 1992; Fröhlich et al., 1996; Nieber et al., 1997). Despite this, little is known about the physiological consquences of ATP when administered in the LC in vivo with the exception of nociception (Fukui et al., 2004). The present study provides the first functional evidence that microinjections of ATP and α,β-meATP directly within the LC of the anaesthetised rat elicit dose-related depressor and bradycardic responses. Furthermore, these responses appear to be highly specific and restricted to the activation of LC neurones only, as microinjection of ATP or α,β-meATP into sites outside of the LC results in either a pressor response (α,β-meATP only) or no response at all. In addition, P2 purinoceptor blockade with two different antagonists was seen to mediate pressor responses, suggesting that ATP is tonically released within the rat LC and presumably, acting via P2X purinoceptors, exerts modulation over the cardiovascular system.

The investigation into the effects of P2-purinoceptor antagonists on BP and HR yielded some interesting results. While the administration of an NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, does not appear to have any cardiovascular effects (Sved & Felsten, 1987; Yao et al., 1999), microinjection of either suramin or PPADS into the LC of an anaesthetised rat increased both BP and HR. In contrast, the P2X1 receptor selective antagonist, NF-279, failed to elicit changes in BP and HR. This difference is most likely a result of blocking only one P2X receptor subtype (namely, P2X1) in the case of NF-279, whereas suramin and PPADS have been shown to affect multiple subtypes of P2X receptors (Humphrey et al., 1995; Ralevic & Burnstock, 1998; Lambrecht, 2000). Furthermore, while suramin does not fully differentiate between P2X and P2Y receptors, PPADS is more selective for P2X receptors over P2Y receptors (McLaren et al., 1994; Lambrecht, 2000). The lack of effect of NF-279 would suggest that P2X1 receptors are not the predominant subtype involved in mediating the responses to ATP. In addition, while PPADS does not generally discriminate between P2X subtypes, both P2X4 and P2X6 subunits (but interestingly not the P2X4/6 heterodimer) have been reported to be insensitive to both PPADS and suramin (Buell et al., 1996; Collo et al., 1996). It is perhaps of some importance to note that much of the pharmacology of P2X and P2Y receptors has been performed on in vitro expression systems and hence may differ from in vivo preparations.

Therefore, one could surmise that the apparent sympathoinhibitory responses of ATP are likely to be mediated via P2X2, P2X3, P2X5 receptors or P2X2/3, P2X4/6 heterodimers. The fact that responses to α,β-meATP do not rapidly desensitise may tip the balance in favour of P2X2/3 heterodimers, although confirmation of this awaits the availability of subtype-selective competitive antagonists. Molecular and immunohistochemical studies have provided considerable evidence that LC neurones express multiple subunits of both P2X and P2Y receptors (Bo & Burnstock, 1994; Balcar et al., 1995; Kidd et al., 1995; Lewis et al., 1995; Soto et al., 1996; Vulchanova et al., 1997; Kanjhan et al., 1999; Yao et al., 2000).

Of interest were the ATP- (and L-GLU-) mediated pressor responses observed following P2-purinoceptor blockade. It has been suggested that in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), ATP may cause a depressor response prior to being metabolised to adenosine, which in turn mediates a pressor response (Ergene et al., 1994). As such, following blockade of P2-purinoceptors (in this case with suramin) the catabolism of ATP to adenosine might mediate the pressor response (Ergene et al., 1994). However, we failed to observe any changes in BP and HR when a high dose of adenosine (0.5 nmol) was injected into the LC, either before or after P2-purinoceptor blockade. Hence the pressor response we observed does not appear to be elicited by adenosine. While recent studies have indicated a role for adenosine as well as ATP in synaptic transmission within the LC (Kuwahata, 2004), other similar studies concluded that adenosine was apparently released during hypoxia within the LC. Furthermore, while exogenous adenosine inhibited the spontaneous firing of LC neurones in a slice preparation, antagonism of adenosine receptors had no impact on spontaneous firing but did antagonise the effects of applied adenosine (Nieber et al., 1995). Consequently, it is possible that while adenosine can modulate the activity of LC neurones, these neurones may ultimately mediate physiological functions other than cardiovascular regulation. Alternatively, it is possible that adenosine may differentially modulate blood flow to various visceral organs such that ‘global' cardiovascular parameters may appear unchanged. Further studies will undoubtedly shed more light on this issue.

Following electrical stimulation of the LC in anaesthetised rats, Drolet & Gauthier (1985) described an initial rapid pressor phase followed by a more prolonged secondary pressor phase; the first phase of this response was abolished by destruction of peripheral sympathetic fibres via intravenous administration of 6-hydroxydopamine while the secondary phase was eliminated by either bilateral adrenalectomy or adrenal demedullation. Midbrain transection eliminated the secondary phase of the response while the initial phase remained intact. These observations suggest that the pressor responses are mediated via activation of the hypothalamo-adrenal axis, a premise supported by earlier findings (Gurtu et al., 1982); however, a sympathetic component is also clearly suggested. The technique of electrical stimulation has come under much scrutiny in more recent years as it has been shown to not only stimulate neuronal cell bodies but also fibres of passage (Crawley et al., 1980; Sved & Felsten, 1987). As such, the pressor role for the LC has also been questioned. However, a recent study suggested that the LC may have the capacity to evoke pressor (in addition to depressor) responses during certain situations such as severe haemorrhage (Anselmo-Franci et al., 1998). The study by Anselmo-Franci and colleagues demonstrated that following lesions of the posterior LC there was a much greater decrease in BP in response to haemorrhage than that observed in anterior LC lesioned and sham-operated rats. As such, the posterior LC appears to play a pressor role during certain situations (e.g. haemorrhage). It is cogent to note, however, that the destruction of the LC via these electrolytic lesions may also destroy fibres of passage passing through the LC from other structures that may impact upon the interpretation of these data. Hence, the future use of fibre-sparing chemical lesions may provide a clearer understanding of LC function under such paradigms.

The concept of ATP and NA cotransmission has been widely accepted and reported both in the periphery and CNS (von Kügelgen & Starke, 1991; von Kügelgen et al., 1994a; Poelchen et al., 2001). At sympathetic nerve terminals, NA stimulation of presynaptic α2-adrenoceptors appears to block N-type Ca2+ channels via G-protein activation resulting in the inhibition of neurotransmitter release (Lipscombe et al., 1989). ATP, however, appears to have a dual effect on neurotransmitter release; facilitation via presynaptic P2X receptors and inhibition via the stimulation of presynaptic P2Y receptors (Boehm, 1999). On LC neurones, postsynaptic α2-adrenoceptors have been shown conclusively to mediate hyperpolarisation (Aghajanian & VanderMaelen, 1982; Poelchen et al., 2001), while both P2X and P2Y receptors have been shown to depolarise LC neurones (Harms et al., 1992; Shen & North, 1993; Scheibler et al., 2004). In addition, the terminals of LC neurones appear to express P2Y receptors, which inhibit the release of NA (von Kügelgen et al., 1994b). From these observations, NA clearly plays a vital role in the regulation of LC neuronal activity. As such, in order to gain a better understanding of the role of NA in the central modulation of the cardiovascular system at the level of the LC, the effects of the α2-adrenoceptor antagonist, idazoxan, were investigated.

Following the identification of an ATP depressor site, the application of idazoxan had no significant effects on BP or HR, nor did it impact upon the effects of subsequent microinjections of ATP. These findings suggest that NA in the LC is unlikely to play a significant role in the maintenance of resting BP and HR. However, when applied in conjunction with PPADS in the form of an antagonist ‘cocktail', idazoxan prevented the characteristic pressor and tachycardic response to PPADS (when applied alone), in addition to the hypertension observed following the application of ATP or L-GLU after P2-purinoceptor blockade. Therefore, the apparent inhibition of PPADS/suramin-sensitive P2-purinoceptors may facilitate the release of NA from LC neurones that subsequently leads to activation of α2-adrenoceptors that mediate the pressor and tachycardic responses. Hence, the coapplication of idazoxan abolished the pressor response normally elicited by PPADS or suramin application. Moreover, during blockade of P2-purinoceptors, the subsequent application of exogenous ATP may stimulate (via facilitatory presynaptic P2X receptors) the further release of NA resulting in the profound pressor and tachycardic response that can be abolished by the administration of an α2-adrenoceptor antagonist. A similar situation is most likely to occur following microinjection of L-GLU subsequent to the administration of the PPADS/idazoxan mixture. L-GLU (following PPADS or suramin application) is likely to stimulate the release of NA, which mediates the hypertension/tachycardia; however, in the presence of idazoxan these responses are severely attenuated. It is worthy and perhaps of some importance to note that the depressor responses to ATP and L-GLU are restored within 60–90 min following the application of the PPADS/idazoxan antagonist mixture, indicating that LC neurones were not subject to any significant amounts of chemical or physical trauma during the entire microinjection procedure. Furthermore, in experiments where the PPADS/idazoxan mixture was substituted with aCSF, a depressor response to ATP was observed 10 min after the aCSF application, highlighting the specific effects of the antagonist mixture.

It is therefore apparent that purines are tonically released in the rat LC and further that there appears to be a functional interaction between purinergic and noradrenergic systems within the rat LC. Notably, the present data suggesting functional interplay between ATP and NA within the LC are supported by electrophysiological studies that indicate ATP/NA cotransmission within the rat LC (Poelchen et al., 1999). Thus, ATP may be released either from dendrites or from recurrent axon collaterals of A6 cells to provide an excitatory counterbalance to the inhibitory noradrenergic drive of these neurones (Illes et al., 1994). Alternatively, it is possible that an excitatory (purinergic) afferent to the LC may originate either in the NTS (Van Bockstaele et al., 1999), or in the nucleus paragigantocellularis (PGi), although in the latter case L-GLU is thought to be the primary transmitter (Ennis & Aston-Jones, 1986; 1988).

These data represent a novel demonstration of centrally mediated purinergic involvement in a physiological role, and also add to our knowledge surrounding the functional capability of the LC. From a functional point of view, the LC appears to be more sensitive to changes in blood volume rather than pressure (Svensson & Thorén, 1979; Elam et al., 1985). Furthermore, vasopressin can act within the LC to mediate pressor responses (Berecek et al., 1984) and the LC can modulate hypothalamic secretion of vasopressin (Lightman et al., 1984). It has recently been suggested that the LC may mediate compensatory changes during hypovolaemia via exerting a pressor role (Anselmo-Franci et al., 1998). While the purinergic system appears to be an important mediator of cardiovascular-related function in the LC, its role in respiratory control was beyond the initial scope of the study and as such was not investigated. There are suggestions that purinergic signalling plays a role in respiratory control at medullary centres such as the rostral ventrolateral medulla (Gourine et al., 2003). Whether this also applies to the LC awaits further investigation.

Taken together the results of the present study demonstrate, for the first time, that blockade of P2X purinoceptors can alter the physiological function of the LC. Thus, depressor agents under ‘normal' physiological conditions, ATP and L-GLU elicit pressor responses after P2X purinoceptor antagonism. Clearly, this ability might be advantageous during certain situations (e.g. as part of a concerted response to haemorrhage), although dysfunction of the coupling between ATP and P2X purinoceptors might convert an ATP/L-GLU mediated depressor response (under ‘normal' physiological states) into a pressor response in pathophysiological states, such as hypertension.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia of which AJL is a Senior Research Fellow. We thank Professor J.F.R. Paton for critically reading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- α,β-meATP

α,β-methyleneATP

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- ATP

adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- Bar

Barrington's nucleus

- BP

blood pressure

- b.p.m.

beats per minute

- CGPn

central pontine grey

- HR

heart rate

- IDA

idazoxan

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.v.

intravenous

- LC

locus coeruleus

- L-GLU

L-glutamate

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- Me5

mesencephalic trigeminal nucleus

- MPB

medial parabrachial nucleus

- NA

noradrenaline

- NF-279

8,8′-[carbonylbis(imino-4,1-phenylenecarbonylimino-4,1-phenylenecarbonylimino)]bis-1,3,5-naphthalenetrisulphonic acid hexasodium

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarius

- Pgi

paragigantocellularis

- PPADS

pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulphonic acid

- SubC

nucleus subcoeruleus

References

- ABRAHAMS T.P., LIU W., VARNER K.J. Blockade of alpha-2 adrenergic receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla attenuates the sympathoinhibitory response to cocaine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;279:967–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGHAJANIAN G.K., VANDERMAELEN C.P. α2-Adrenoceptor-mediated hyperpolarization of locus coeruleus neurons: intracellular studies in vivo. Science. 1982;215:1394–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.6278591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANSELMO-FRANCI J.A., PERES-POLON V.L., DA ROCHA-BARROS V.M., MOREIRA E.R., FRANCI C.R., ROCHA M.J. C-fos expression and electrolytic lesion studies reveal activation of the posterior region of locus coeruleus during hemorrhage induced hypotension. Brain Res. 1998;799:278–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASTON-JONES G., AKAOKA H., CHARLETY P., CHOUVET G. Serotonin selectively attenuates glutamate-evoked activation of noradrenergic locus coeruleus neurons. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:760–769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00760.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASTON-JONES G., BLOOM F.E. Activity of norepinephrine containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep–wake cycle. J. Neurosci. 1981;13:876–886. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-08-00876.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASTON-JONES G., ENNIS M., PIERIBONE V.A., NICKELL W.T., SHIPLEY M.T. The brain nucleus locus coeruleus: restricted afferent control of a broad efferent network. Science. 1986;234:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.3775363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BALCAR V.J., LI Y., KILLINGER S., BENNETT M.R. Autoradiograpy of P2X ATP receptors in the rat brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:302–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERECEK K.H., OLPE H.R., HOFBAUER K.G. Responsiveness of locus ceruleus neurons in hypertensive rats to vasopressin. Hypertension. 1987;9:III110–III113. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.6_pt_2.iii110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERECEK K.H., OLPE H.R., JONES R.S., HOFBAUER K.G. Microinjection of vasopressin into the locus coeruleus of conscious rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1984;247:H675–H681. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.247.4.H675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHASKARAN D., FREED C.R. Changes in neurotransmitter turnover in locus coeruleus produced by changes in arterial blood pressure. Brain Res. Bull. 1988;21:191–199. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BO X., BURNSTOCK G. Distribution of [3H]α,β-methylene ATP binding sites in rat brain and spinal cord. NeuroReport. 1994;5:1601–1604. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199408150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOEHM S. ATP stimulates sympathetic transmitter release via presynaptic P2X purinoceptors. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:737–746. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00737.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUELL G., LEWIS C., COLLO G., NORTH R.A., SURPRENANT A. An antagonist-insensitive P2X receptor expressed in epithelia and brain. EMBO J. 1996;15:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. The past, present and future of purine neucleotides as signalling molecules. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1127–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CEDARBAUM J.M., AGHAJANIAN G.K. Noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus: inhibition by epinephrine and activation by the alpha-antagonist piperoxane. Brain Res. 1976;112:413–419. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLO G., NORTH R.A., KAWASHIMA E., MERLO-PICH E., NEIDHART S., SURPRENANT A., BUELL G. Cloning of P2X5 and P2X6 receptors and the distribution and properties of an extended family of ATP-gated ion channels. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:2495–2507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02495.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRAWLEY J.N., MAAS J.W., ROTH R.H. Evidence against specificity of electrical stimulation of the nucleus locus coeruleus in activating the sympathetic nervous system in the rat. Brain Res. 1980;183:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAHLOF C., ENGBERG G., SVENSSON T.H. Effects of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists on the firing rate of noradrenergic neurones in the locus coeruleus of the rat. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1981;317:26–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00506252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DROLET G, GAUTHIER P. Peripheral and central mechanisms of the pressor reponse elicited by stimulation of the locus coeruleus in the rat. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1985;63:599–605. doi: 10.1139/y85-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELAM M., SVENSSON T.H., THORÉN P. Differentiated cardiovascular afferent regulation of locus coeruleus neurons and sympathetic nerves. Brain Res. 1985;358:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90950-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENNIS M., ASTON-JONES G. A potent excitatory input to the nucleus locus coeruleus from the ventrolateral medulla. Neurosci. Lett. 1986;71:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90637-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENNIS M., ASTON-JONES G. Activation of locus coeruleus from nucleus paragigantocellularis: a new excitatory amino acid pathway in brain. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:3644–3657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-10-03644.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERGENE E., DUNBAR J.C., O'LEARY D.S., BARRACO R.A. Activation of P2-purinoceptors in the nucleus tractus soliatrius mediate depressor responses. Neurosci. Lett. 1994;174:188–192. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FOOTE S.L., BLOOM F.E., ASTON-JONES G. Nucleus locus ceruleus: new evidence of anatomical and physiological specificity. Physiol. Rev. 1983;63:844–914. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.3.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRÖHLICH R., BOEHM S., ILLES P. Pharmacological characterization of P2 purinoceptor types in rat locus coeruleus neurons. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;315:255–261. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUKUI M., TAKISHITA A., ZHANG N., NAKAGAWA T., MINAMI M., SATOH M. Involvement of locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons in supraspinal antinociceptin by alpha,beta-methylene-ATP in rats. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;94:153–160. doi: 10.1254/jphs.94.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOURINE A.V., ATKINSON L., DEUCHARS J., SPYER K.M. Purinergic signalling in the medullary mechanisms of respiratory control in the rat: respiratory neurones express the P2X2 receptor subunit. J. Physiol. (London) 2003;552:197–211. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURTU S., SINHA J.N., BHARGAVA K.P. Involvement of alpha2-adrenoceptors of nucleus tractus solitarius in baroreflex mediated bradycardia. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1982;321:38–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00586346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARMS L., FINTA E.P., TSCHOPL M., ILLES P. Depolarization of rat locus coeruleus neurons by adenosine 5′-triphosphate. Neuroscience. 1992;48:941–952. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUMPHREY P.P., BUELL G., KENNEDY I., KHAKH B.S., MICHEL A.D., SURPRENANT A., TREZISE D.J. New insights on P2X purinoceptors. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1995;352:585–596. doi: 10.1007/BF00171316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILLES P., SEVCIK J., FINTA E.P., FROHLICH R., NIEBER K., NORENBERG W. Modulation of locus coeruleus neurons by extra- and intracellular adenosine 5′-triphosphate. Brain Res. Bull. 1994;35:513–519. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANJHAN R., HOUSLEY G.D., BURTON L.D., CHRISTIE D.L., KIPPENBERGER A., THORNE P.F., LUO L., RYAN A.F. Distribution of the P2X2 receptor subunit of the ATP-gated ion channels in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;407:11–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIDD E.J., GRAHAMES C.B., SIMON J., MICHEL A.D., BARNARD E.A., HUMPHREY P.P. Localization of P2X purinoceptor transcripts in the rat nervous system. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUWAHATA T. Effects of adenosine and ATP on the membrane potential and synaptic transmission in neurons of the rat locus coeruleus. Kurume Med. J. 2004;51:109–123. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.51.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMBRECHT G. Agonists and antagonists acting at P2X receptors: Selectivity profiles and functional implications. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:340–350. doi: 10.1007/s002100000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAMBRECHT G., FRIEBE T., GRIMM U., WINDSCHEIF U., BUNGARDT E., HILDEBRANDT C., BAUMERT H.G., SPATZ-KUMBLE G., MUTSCHLER E. PPADS, a novel functionally selective antagonist of P2 purinoceptor-mediated responses. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;217:217–219. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90877-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS C., NEIDHART S., HOLY C., NORTH R.A., BUELL G., SURPRENANT A. Coexpression of P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits can account for ATP-gated currents in sensory neurons. Nature. 1995;377:432–434. doi: 10.1038/377432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIGHTMAN S.L., TODD K., EVERITT B.J. Ascending noradrenergic projections from the brainstem: evidence for a major role in the regulation of blood pressure and vasopressin secretion. Exp. Brain Res. 1984;55:145–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00240508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIPSCOMBE D., KONGSAMUT S., TSIEN R.W. Adrenergic inhibition of sympathetic neurotransmitter release mediated by modulation of N-type calcium channel gating. Nature. 1989;340:639–642. doi: 10.1038/340639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATEO J., GARCIA LECEA M., MIRAS PORTUGAL M.T., CASTRO E. Ca2+ signals mediated by P2X-type purinoceptors in cultured cerebellar granular Purkinje cells. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:1704–1712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01704.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAREN G.J., LAMBRECHT G., MUTSCHLER E., BAUMERT H.G., SNEDDON P., KENNEDY C. Investigation of the actions of PPADS, a novel P2X-purinoceptor antagonist, in the guinea-pig isolated vas deferens. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;111:913–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYAWAKI T., KAWAMURA H., HARA K., SUZUKI K., USUI W., YASUGI T. Differential regional hemodynamic changes produced by L-glutamate stimulation of the locus coeruleus. Brain Res. 1993;600:56–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURASE S., TAKAYAMA M., NOSAKA S. Chemical stimulation of the nucleus locus coeruleus: cardiovascular responses and baroreflex modification. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;153:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90062-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIEBER K., POELCHEN W., ILLES P. Role of ATP in fast excitatory synaptic potentials in locus coeruleus neurones of the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:423–430. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIEBER K., SEVCIK J., ILLES P. Hypoxic changes in rat locus coeruleus neurons in vitro. J Physiol. 1995;486:33–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLPE H.R., BERECEK K., JONES R.S., STEINMANN M.W., SONNENBURG C., HOFBAUER K.G. Reduced activity of locus coeruleus neurons in hypertensive rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1985;61:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAXINOS G., WATSON C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates 1986New York: Academic Press; 2nd edn. [Google Scholar]

- POELCHEN W., SIELER D., ILLES P.Evidence for co-release of norepinephrine and ATP from nerve terminals of rat locus coeruleus neurons Society for Neuroscience, Abstract 1999411–481.Vol. 25 p.

- POELCHEN W., SIELER D., WIRKNER K., ILLES P. Co-transmitter function of ATP in central catecholaminergic neurons of the rat. Neuroscience. 2001;102:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00529-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RALEVIC V., BURNSTOCK G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHEIBLER P., PESIC M., FRANKE H., REINHARDT R., WIRKNER K., ILLES P., NORENBERG W. P2X2 and P2Y1 immunofluorescence in rat neostriatal medium-spiny projection neurones and cholinergic interneurones is not linked to respective purinergic receptor function. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;143:119–131. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEN K.Z., NORTH R.A. Excitation of rat locus coeruleus neurons by adenosine 5′-triphosphate: ionic mechanism and receptor characterization. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:894–899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-00894.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGEWALD N., PHILIPPU A. Catecholamine release in the locus coeruleus is modified by experimentally induced changes in haemodynamics. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1993;347:21–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00168767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOTO F., GARCIA-GUZMAN M., GOMEZ-HERNANDEZ J.M., HOLLMANN M., KARSCHIN C., STUHMER W. P2X4: an ATP-activated ionotropic receptor cloned from rat brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:3684–3688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SVED A.F., FELSTEN G. Stimulation of the locus coeruleus decreases arterial pressure. Brain Res. 1987;414:119–132. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91332-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SVENSSON T.H., THORÉN P. Brain noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus: inhibition by blood volume load through vagal afferents. Brain Res. 1979;172:174–178. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSCHOPL M., HARMS L., NORENBERG W., ILLES P. Excitatory effects of adenosine 5′-triphosphate on rat locus coeruleus neurones. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;213:71–77. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90234-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN BOCKSTAELE E.J., PEOPLES J., TELEGAN P. Efferent projections of the nucleus of the solitary tract to peri-locus coeruleus dendrites in rat brain: Evidence for a monosynaptic pathway. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;412:410–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990927)412:3<410::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON KÜGELGEN I., ALLGAIER C., SCHOBERT A., STARKE K. Co-release of noradrenaline and ATP from cultured sympathetic neurons. Neuroscience. 1994a;61:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90223-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON KÜGELGEN I., SPÄTH L., STARKE K. Evidence for P2-purinoceptor-mediated inhibition of noradrenaline release in the rat brain cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994b;113:815–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON KÜGELGEN I., STARKE K. Noradrenaline-ATP co-transmission in the sympathetic nervous system. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1991;12:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90587-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VULCHANOVA L., RIEDL M.S., SHUSTER S.J., BUELL G., SURPRENANT A., NORTH R.A., ELDE R. Immunohistochemical study of the P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits in rat and monkey sensory neurons and their central terminals. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1229–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO S.T., BARDEN J.A., FINKELSTEIN D.I., BENNETT M.R., LAWRENCE A.J. Comparative study on the distribution patterns of P2X1-P2X6 receptor immunoreactivity in the brainstem of the rat and common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus): association with catecholamine cell groups. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000;427:485–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO S.T., FINKELSTEIN D.I., LAWRENCE A.J. Nitrergic stimulation of the locus coeruleus modulates blood pressure and heart rate in the anaesthetized rat. Neuroscience. 1999;91:621–629. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00661-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]