Abstract

The contractile mechanism of N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine (fMLP) was investigated in the guinea-pig Taenia coli, by simultaneously monitoring the changes in the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and force.

fMLP induced a significant elevation of [Ca2+]i and force at concentrations higher than 10 nM. The maximal response was obtained at a concentration of higher than 1 μM.

fMLP (10 μM) augmented the force development induced by a stepwise increment of the extracellular Ca2+ concentration during 60 mM K+ depolarization, while it had no effect on the [Ca2+]i elevation, and thus produced a greater force for a given elevation of [Ca2+]i than 60 mM K+ depolarization.

The removal of extracellular Ca2+ completely abolished the fMLP-induced contraction. The fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation was inhibited substantially but not completely by 10 μM diltiazem, partly by 10 μM SK&F 96365, and completely by their combination.

Y27632, a specific inhibitor of rho-kinase, had no significant effect on the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and force development.

Chenodeoxycholic acid, a formyl peptide receptor antagonist, specifically abolished the fMLP-induced contraction but not high K+- or carbachol-induced contractions.

A dual lipoxygenase/cyclooxygenase inhibitor, a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, a nonselective leukotriene receptor antagonist, and a selective type 1 cysteinyl-containing leukotriene receptor antagonist specifically reduced the fMLP-induced contraction.

We suggest that the low-affinity-type fMLP receptor and lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid are involved in the fMLP-induced contraction in the guinea-pig T. coli. This contraction mainly depends on the [Ca2+]i elevation due to Ca2+ influx and the enhancement of Ca2+ sensitivity in the contractile apparatus.

Keywords: Ca2+ sensitivity, fMLP, gastrointestinal smooth muscle

Introduction

N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine (fMLP), a synthetic analogue of bacterial chemotactic peptide (Schiffmann et al., 1975a, 1975b; Marasco et al., 1984), exerts a potent chemoattractant effect toward neutrophils and monocytes. In addition to this effect, fMLP has been shown to possess spasmogenic properties in smooth muscle tissues including airway, blood vessels, intestinal tract, and renal pelvis (Hamel et al., 1984; Armour et al., 1986; Boukili et al., 1986; Shore et al., 1987; Crowell et al., 1989; Maggi et al., 1992; Minamino et al., 1996). The mechanism for the fMLP-induced contraction appeared to vary with type of smooth muscle tissue. Many studies have suggested an indirect contractile mechanism in the human bronchus, guinea-pig lung parenchymal strips, human coronary artery, and rabbit pulmonary artery (Hamel et al., 1984; Armour et al., 1986; Shore et al., 1987; Crowell et al., 1989; Keitoku et al., 1997). The cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid, such as thromboxane A2 and leukotriene C4, were suggested to mediate the contractile response of fMLP, based on the observation that the inhibitors of cyclooxygenase (Hamel et al., 1984; Shore et al., 1987; Crowell et al., 1989; Keitoku et al., 1997), lipoxygenase (Shore et al., 1987) and thromboxane synthase (Shore et al., 1987), or leukotriene receptor antagonist (Armour et al., 1986; Shore et al., 1987) inhibited the fMLP-induced contraction. The fMLP-activated neutrophils have also been shown to induce endothelium-dependent contraction in the human umbilical vein and canine coronary artery (Minamino et al., 1996; Kerr et al., 1998). On the other hand, the direct contractile effect of fMLP has only been suggested in the guinea-pig ileum (Marasco et al., 1982). Furthermore, the cellular mechanism for fMLP-induced contraction remains to be elucidated, especially in terms of intracellular Ca2+ signal transduction.

The cellular effect of fMLP is mediated by formyl peptide receptors. Three genes for humans (formyl peptide receptor (FPR), FPRL1, and FPRL2) and eight genes for mice (FPR1, FPR-rs1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) have been identified as FPR gene family (Bao et al., 1992; Gao et al., 1998; Wang & Ye, 2002). This receptor family belongs to a superfamily of a seven-transmembrane, G-protein-coupled receptor (Prossnitz & Ye, 1997). Among these receptors, FPR and FPRL1 in humans and FPR1 and FPR-rs1 in mice could serve as functional receptors for fMLP. The cellular distribution of the high-affinity FPR is not restricted to phagocytic leukocytes as originally proposed, but it is expressed on a broad spectrum of tissues and cells, including neuromuscular, vascular, endocrine, and immune systems (Lacy et al., 1995; McCoy et al., 1995; Sozzani et al., 1995; Becker et al., 1998; Panaro & Mitolo, 1999). FPRL1 is also expressed in a variety of cell types including phagocytic leukocytes, lymphocytes, hepatocytes, epithelial cells, neuroblastoma cells, astrocytoma cells, and microvascular endothelial cells (Gronert et al., 1998; Le et al., 2000). However, the receptor responsible for the fMLP-induced contractile responses remains to be identified.

In the present study, we investigated the mechanism of the fMLP-induced contraction in the guinea-pig Taenia coli, by simultaneously monitoring the cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i) and force development in the fura-PE3-loaded strips. The cellular mechanism of the fMLP-induced contraction was investigated in terms of Ca2+ signaling, by examining the effect of the removal of the extracellular Ca2+, two Ca2+ entry blockers, and a rho-kinase inhibitor. The receptor mediating the fMLP-induced contraction in the guinea-pig T. coli was evaluated by examining the effects of various receptor antagonists including chenodeoxycholic acid, the formyl peptide receptor antagonist, on the fMLP-induced contraction. We also investigated the involvement of the lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid in the fMLP-induced contraction.

Methods

Tissue preparation

The experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and the Committee of the Research Institute of Angiocardiology, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University. Male Hartley guinea-pigs weighing 350–400 g were killed by the intraperitoneal injection of 250 mg kg−1 weight of nembutal and subsequent exsanguination. After the T. coli was isolated, the mucosa and the circumference muscle layer were mechanically removed under a binocular microscope, and then the longitudinal muscle layer was cut into strips (1 mm wide × 3.5 mm long × 0.5 mm thick) as reported previously (Ieiri et al., 2001).

Fura-PE3 loading

The guinea-pig T. coli strips were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator dye, fura-PE3 in the form of acetoxymethyl ester by incubation in oxygenated (a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2) Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 50 μM fura-PE3 acetoxymethyl ester dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide, 5% fetal bovine serum, and 0.02% Pluronic F-127 for 8 h at 37°C (Ieiri et al., 2001). After loading with fura-PE3, the strips were rinsed in normal physiological salt solution (PSS) to remove the dye remaining in the extracellular space, and then were equilibrated in normal PSS for about 1 h before starting the experimental protocols.

Front-surface fluorometry

The changes in the fluorescence intensity of Ca2+–fura-PE3 complex of the strips of T. coli were monitored with front-surface fluorometry at 37°C, as reported previously (Hirano et al., 1990; Kanaide, 1999; Ieiri et al., 2001). The fluorescence (500 nm) intensities at 340 (F340) and 380 nm (F380) excitation were monitored, and their ratio (F340/F380) was recorded as an indication of [Ca2+]i. The level of the fluorescence ratio obtained at rest (in 5.9 mM K+, 2.5 mM Ca2+-containing normal PSS, and in the absence of any inhibitors) and that obtained at a steady state of contraction induced by 60 mM K+ depolarization were assigned to be 0 and 100%, respectively, in all data analyses.

Measurement of force development

The strips of T. coli were mounted vertically in a quartz organ bath. One end of the strips was connected to a fixed hook, while the other end was connected to a strain gauge (TB-612-T, Nihon Koden, Japan). The strip was stimulated with 60 mM K+ depolarization every 15 min with a stepwise increase in the resting load until a maximal response was obtained. The optimal resting load thus determined was about 0.7 g. All experimental procedure was performed in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin. The presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin did not affect the force development induced by 60 mM K+. High K+ depolarization at this concentration reproducibly induces the maximum force development. The level of force obtained at rest (in 5.9 mM K+ and 2.5 mM Ca2+-containing normal PSS, and in the absence of any inhibitors) and that obtained at a steady state of contraction induced by 60 mM K+ PSS were assigned to be 0 and 100%, respectively, in all data analyses.

Solutions and chemicals

The composition of the normal (5.9 mM K+) PSS was as follows (in mM): NaCl 123, KCl 4.7, NaHCO3 15.5, KH2PO4 1.2, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2.5, and D-glucose 11.5. The solution containing higher concentrations of K+ was prepared by adding KCl to the normal PSS. A Ca2+-free solution was prepared by omitting CaCl2 from normal PSS and adding 0.3 mM ethyleneglycol-bis (β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′,-tetraacetic acid (EGTA). PSS was gassed with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2, with the resulting pH being 7.4. Aspirin, Atropine, BAY u9773, carbamylcholine chloride (carbachol), chenodeoxycholic acid, [des-Arg10]-HOE 140, HOE 140, famotidine, fMLP, indomethacin, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, phenidone, and pyrilamine were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Fura-PE3 acetoxymethyl ester was purchased from Texas Fluorescence Laboratory (Austin, TX, U.S.A.). Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.). Y27632 and SK&F 96365 were purchased from Calbiochem (California, U.S.A.). Tetrodotoxin was purchased from Wako (Osaka, Japan). EGTA was purchased from Dojindo (Kumamoto, Japan). MK-571 and U-75302 were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.). ONO1078 was a kind gift from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Osaka, Japan). SR 140333 and SR 48968 were generous gifts from Sanofi-Synthelabo (Paris, France). BAY u9773, indomethacin, nordihydroguaiaretic acid, phenidone, and U-75302 were dissolved in ethanol. fMLP, MK-571, and ONO1078 were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide. All other chemicals were dissolved in distilled water.

Data analysis

All data from the simultaneous measurements of [Ca2+]i and force were collected using a computerized data acquisition system (MacLab; Analog Digital instruments, Castle Hill, Australia; Macintosh, Apple Computer, Cupertino, CA, U.S.A.). The representative traces shown were directly printed from the data obtained using this system. All data are the mean±s.e.m. (n=number of the experiments). A strip obtained from one animal was used for each experiment; therefore, the n value indicates the number of animals. A statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student's t-test or a repeated measure analysis of variance. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

fMLP induces sustained elevations of [Ca2+]i and force in the guinea-pig T. coli

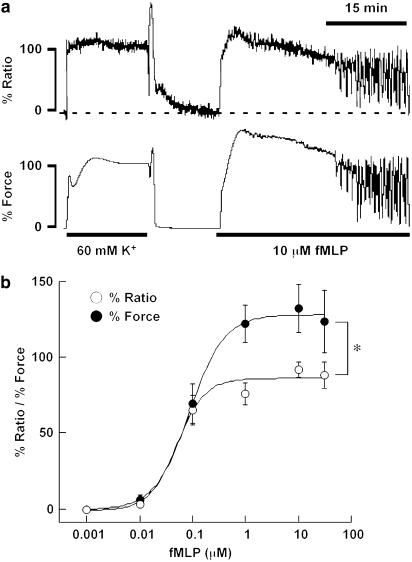

The application of 10 μM fMLP induced a sustained contraction in the guinea-pig T. coli (Figure 1a). fMLP induced a rapid elevation of [Ca2+]i, while reaching a peak within 4 min. Thereafter, [Ca2+]i slightly decreased to a sustained level. On the other hand, the force rapidly developed after the application of 10 μM fMLP, and reached a sustained level within 4 min. It is worth noting that there was a lag time after the application of fMLP until the [Ca2+]i and force started to increase. The lag times for [Ca2+]i and force were 28.8±0.1 and 31.1±0.1 s (n=9), respectively (Figure 1b). The sustained level of [Ca2+]i and force was maintained for about 15 min and then gradually decreased. A significant elevation of [Ca2+]i and force was observed at the concentrations higher than 0.01 μM, and the EC50 values for [Ca2+]i and force were 0.055 and 0.099 μM (n=5–9), respectively. On the other hand, 60 mM K+ depolarization induced an abrupt elevation of [Ca2+]i and force, without any obvious lag times (Figure 1). The level of [Ca2+]i and the force obtained at rest (in 5.9 mM K+, 2.5 mM Ca+-containing normal PSS) and that obtained at a steady state of contraction induced by 60 mM K+ were assigned to be 0 and 100%, respectively. Therefore, any change below the resting level resulted in a negative value. Importantly, the [Ca2+]i elevation obtained with fMLP was significantly (P<0.05) lower than the force development, thus suggesting that the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus was enhanced by fMLP.

Figure 1.

Changes in the [Ca2+]i and force induced by fMLP in the strips of guinea-pig T. coli. (a) A representative recording showing the changes in [Ca2+]i and force induced by 10 μM fMLP in normal PSS. The level of [Ca2+]i and force at rest (5.9 mM K+–PSS) and at the steady state of contraction induced by 60 mM K+ depolarization were assigned to be 0 and 100%, respectively. (b) Concentration–response curves for the fMLP-induced maximal elevation of [Ca2+]i and force in the guinea-pig T. coli. The data are the mean±s.e.m. (n=5–9). *Significant (P<0.05).

Effect of fMLP on the [Ca2+]i–force relationships

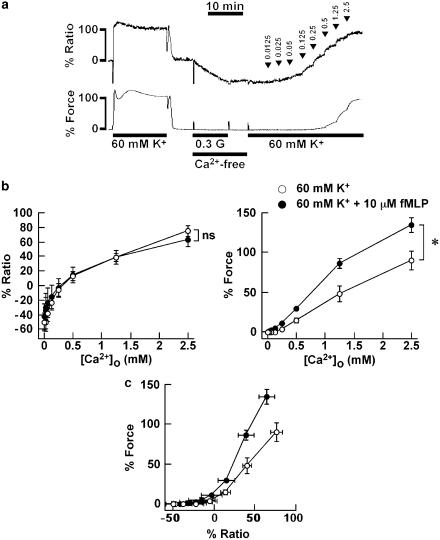

To further evaluate the effect of fMLP on the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus of the guinea-pig T. coli, we examined the effect of fMLP on the change in [Ca2+]i and force induced by the stepwise increment of extracellular Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]o) during the stimulations with 60 mM K+ depolarization. As shown in Figure 2a, after recording the reference response, the strips were exposed to 0.3 mM EGTA-containing Ca2+-free PSS for 10 min and to the Ca2+-free media without EGTA for 5 min, and then stimulated with 60 mM K+ depolarization in the Ca2+-free media. The contraction was then induced by increasing [Ca2+]o from 0 to 2.5 mM in a stepwise manner. In the absence of fMLP, the [Ca2+]i and force increased in a stepwise manner and reached 76.1±7.3 and 89.8±12.4% (n=5), respectively, at [Ca2+]o of 2.5 mM. In order to determine the effect of fMLP on this contraction, 10 μM fMLP was applied 5 min prior to and during the contraction. As shown in Figure 2b, the addition of 10 μM fMLP during the 60 mM K+ depolarization in the Ca2+-free PSS induced no elevation of [Ca2+]i and force, and the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by a stepwise increase in [Ca2+]o in the presence of 10 μM fMLP did not significantly differ from that seen in its absence. However, the development of force was significantly enhanced by the addition of fMLP. The level of [Ca2+]i and force obtained with 2.5 mM [Ca2+]o in the presence of 10 μM fMLP was 63.9±9.4 and 134.9±9.5% (n=4), respectively. Accordingly, the force–[Ca2+]i relationship obtained with fMLP was located on the left of that obtained without fMLP (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Effect of fMLP on the contraction induced by the cumulative application of the extracellular Ca2+ during 60 mM K+ depolarization in the guinea-pig T. coli. (a) A representative recording showing the changes in [Ca2+]i and force induced by the stepwise increment of [Ca2+]o during the 60 mM K+ depolarization in the absence of fMLP. The numbers noted by the arrow heads indicate [Ca2+]o obtained at each step. The level of [Ca2+]i and force at rest (5.9 mM K+–PSS) and at the steady state of contraction induced by the first stimulation with 60 mM K+ depolarization was assigned to be 0 and 100%, respectively, 0.3 G, 0.3 mM EGTA. (b) Summary of the changes in [Ca2+]i (left) and force (right) induced by the cumulative application of [Ca2+]o during 60 mM K+ depolarization in the presence and absence of 10 μM fMLP. fMLP was applied 5 min prior to and during the contraction induced by the application of extracellular Ca2+. The data are the mean±s.e.m. (n=4–5). *Significantly (P<0.05); NS, not significantly (P>0.05) different from the values obtained without fMLP. (c) The [Ca2+]i–force relation curves reconstructed from the data in (b).

Negligible contribution of the intracellular Ca2+ store to the fMLP-induced contraction

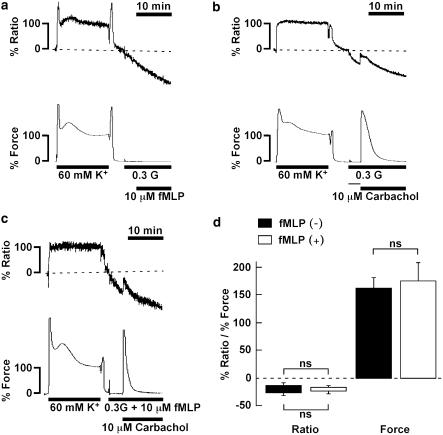

To evaluate the involvement of the Ca2+ release from the intracellular store in the fMLP-induced contraction, we applied 10 μM fMLP in the Ca2+-free PSS containing 0.3 mM EGTA. When the strip was exposed to Ca2+-free PSS containing 0.3 mM EGTA, the [Ca2+]i decreased to −25.7±2.8% (n=12) within 3 min, with no change in the resting force. The depolarization with 60 mM K+ induced no increase in either [Ca2+]i or force, thus indicating that [Ca2+]o was nominally ‘0' (data not shown). In the Ca2+-free PSS containing 0.3 mM EGTA, 10 μM fMLP did not induce any increase in [Ca2+]i and force (Figure 3a). To further examine the role of Ca2+ release in the fMLP-induced contraction, we examined the effect of pretreatment with fMLP on the subsequent response to carbachol. We previously reported the carbachol-induced contraction to be dependent on the [Ca2+]i elevation due to Ca2+ release in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ (Ieiri et al., 2001). As shown in Figure 3b, 10 μM carbachol induced a small transient elevation of [Ca2+]i (from −27.2±4.0 to −14.1±5.8%, n=6) and a large transient development of force (162.0±17.9%, n=6) in the absence of 10 μM fMLP. The pretreatment with 10 μM fMLP had no significant effect on the subsequent changes in [Ca2+]i and force induced by 10 μM carbachol (Figure 3c). The peak levels of [Ca2+]i and force induced by 10 μM carbachol under this condition were −16.9±4.2% (n=6) and 175.6±32.2% (n=6), respectively. There was no difference in the changes in [Ca2+]i and force induced by carbachol in Ca2+-free PSS between the presence and absence of fMLP (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Contractions induced by fMLP and carbachol in the absence of the extracellular Ca2+. (a–c) Representative recordings showing the changes in [Ca2+]i and force induced by 10 μM fMLP (a) and 10 μM carbachol (b and c) in the Ca2+-free PSS containing 0.3 mM EGTA without (b) and with (c) 10 μM fMLP in the guinea-pig T. coli. After recording a reference response to 60 mM K+, the strips were exposed to the Ca2+-free PSS for 3 min, and then were stimulated by fMLP and carbachol. (d) A summary of the increases in [Ca2+]i and force induced by 10 μM carbachol in the Ca2+-free PSS containing 0.3 mM EGTA with and without 10 μM fMLP. The [Ca2+]i and force were expressed as a percentage, assigning the values in normal (5.9 mM K+) PSS and 60 mM K+ PSS to be 0 and 100%, respectively. The bottom and top of each column represent the levels of [Ca2+]i and force obtained just before and at the maximal elevation after stimulation with carbachol, respectively. The data are the mean±s.e.m. (n=5–6). NS, not significantly different (P>0.05).

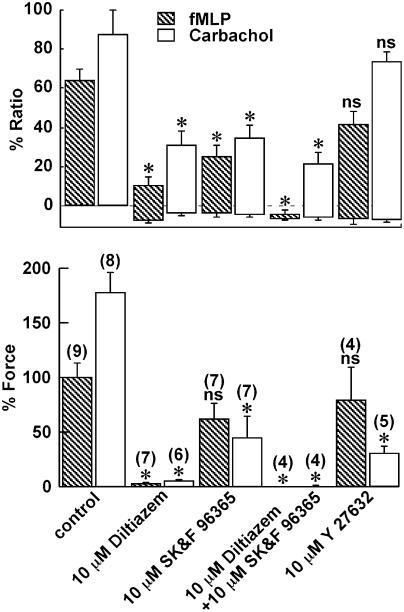

Effects of diltiazem, SK&F 96365 and Y27632 on the increases in [Ca2+]i and force induced by fMLP

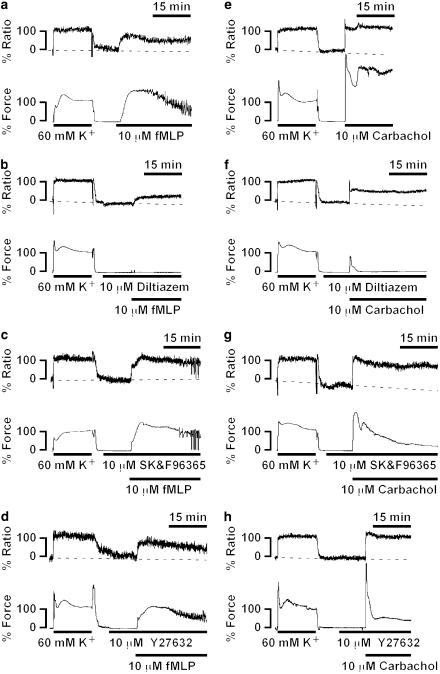

To elucidate the mechanism of the sustained phase of the fMLP-induced contraction seen in the presence of extracellular Ca2+, the effects of two types of Ca2+ entry blocker, diltiazem (a L-type Ca2+ channel blocker) and SK&F 96365 (a receptor-operated Ca2+ channel blocker) (Merritt et al., 1990), and a specific inhibitor of rho-kinase, Y27632 (Uehata et al., 1997), on the fMLP-induced contraction were examined. Since parasympathetic innervation plays an important role in the regulation of intestinal contractility, the effects of these inhibitors on the carbachol-induced contraction were also examined, and compared to those seen with the fMLP-induced contraction. In this measurement series, we used fMLP and carbachol at a concentration of 10 μM to induce their maximal effect. All inhibitors were applied 10 min before and during contraction induced by fMLP and carbachol, and their effects were evaluated at 15 min after the initiation of contraction (Figures 4b and 5). Pretreatment with 10 μM diltiazem, 10 μM SK&F 96365, and 10 μM Y27632 had no statistically significant effects on the resting levels of [Ca2+]i and force. Diltiazem (10 μM) substantially but not completely inhibited the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by fMLP, while it almost completely inhibited the force development (Figure 4b). Higher concentrations of diltiazem did not cause any further inhibition (data not shown). On the other hand, SK&F 96365 partially inhibited the increase in [Ca2+]i, while it had no significant effect on the force development (Figures 4c and 5). The combination of 10 μM diltiazem and 10 μM SK&F 96365 completely abolished the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation (Figure 5). The pretreatment with 10 μM Y27632 had no significant effects on the level of [Ca2+]i and force seen at 15 min after stimulation with fMLP (Figures 4d and 5).

Figure 4.

Effects of diltiazem, SK&F 96365 and Y27632 on the contractions induced by fMLP and carbachol in the guinea-pig T. coli. Representative recordings showing the changes in [Ca2+]i and force induced by 10 μM fMLP (a–d) and 10 μM carbachol (e–h) in the normal PSS without (a and e) and with 10 μM diltiazem (b and f), 10 μM SK&F 96365 (c and g), and 10 μM Y27632 (d and h). Diltiazem, SK&F 96365 and Y27632 were applied 10 min before and during the contraction induced by fMLP and carbachol. The [Ca2+]i and force were expressed as a percentage, assigning the values in normal PSS and 60 mM K+ PSS to be 0 and 100%, respectively.

Figure 5.

Summary of the effects of diltiazem, SK&F 96365, and Y27632 on the increases in [Ca2+]i and force induced by fMLP and carbachol. The effect of 10 μM diltiazem, 10 μM SK&F 96365, 10 μM diltiazem plus 10 μM SK&F 96365, and 10 μM Y27632 on the fMLP-induced contraction were evaluated at 15 min after the initiation of the contraction. The levels of [Ca2+]i and force obtained at rest (in 5.9 mM K+, 2.5 mM Ca2+-containing normal PSS) and those obtained at the steady state of the 60 mM K+-induced contraction were assigned values of 0 and 100%, respectively. The level of the bottom and top of each column indicate the level of [Ca2+]i and force obtained just before and 15 min after initiating the contraction. The data are the mean±s.e.m. of the number of experiments as indicated in parentheses. *Significantly (P<0.05); NS, not significantly (P>0.05) different from the control values.

On the other hand, carbachol induced an abrupt elevation of [Ca2+]i and force development with no obvious lag time, followed by a sustained elevation (Figure 4e). It is worth noting that, in addition to the presence of the lag time in response to fMLP, fMLP-induced slower initial increase in [Ca2+]i, and force than that seen with carbachol (Figures 1a and 4a, e). Diltiazem substantially inhibited the [Ca2+]i elevation during the sustained phase, while it almost completely inhibited the force development (Figures 4f and 5). The initial and transient phase of [Ca2+]i elevation and force development was also significantly inhibited by diltiazem (Figure 4f). SK&F 96365 significantly inhibited the sustained phase of the carbachol-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and force development, while it slightly inhibited the initial phase of [Ca2+]i increase (Figures 4g and 5). Y27632 had no significant effect on both the initial and sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i, while it markedly inhibited the sustained level of force (Figures 4h and 5).

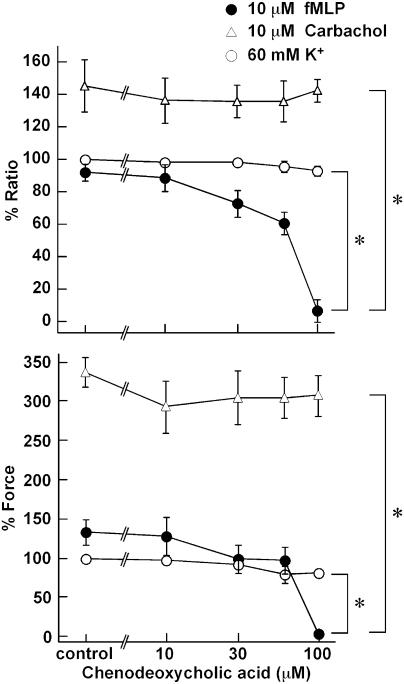

Effects of chenodeoxycholic acid on the fMLP-induced contraction

In order to determine the involvement of formyl peptide receptor in the fMLP-induced contraction, the effect of a formyl peptide receptor antagonist, chenodeoxycholic acid, was examined. Chenodeoxycholic acid (0–100 μM) was applied 10 min before and during the contraction induced by 10 μM fMLP, 10 μM carbachol, and 60 mM K+ depolarization, and its effect was evaluated at the peak of the contraction. As shown in Figure 6, chenodeoxycholic acid inhibited elevation of both [Ca2+]i and force induced by fMLP in a concentration-dependent manner, while demonstrating a complete inhibition at 100 μM. The half-maximum inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of chenodeoxycholic acid for fMLP-induced elevations of [Ca2+]i and force were 59.4 and 63.3 μM, respectively (n=4). On the other hand, chenodeoxycholic acid, at any concentrations examined, had no significant effect on the contraction induced by 10 μM carbachol. The elevation of force induced by 60 mM K+ was significantly but only slightly inhibited by 100 μM chenodeoxycholic acid. However, 1 mM and higher concentrations of chenodeoxycholic acid completely inhibited the contraction induced by not only fMLP but also carbachol and 60 mM K+ (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Concentration-dependent effects of chenodeoxycholic acid on the changes in [Ca2+]i and force induced by fMLP, carbachol, and 60 mM K+ depolarization in the guinea-pig T. coli. After recording a reference response to 60 mM K+ depolarization, the strips were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of chenodeoxycholic acid for 10 min, and then stimulated with 10 μM fMLP, 10 μM carbachol, and 60 mM K+ depolarization in the presence of chenodeoxycholic acid. The levels of [Ca2+]i and force obtained at the peak of the contraction are shown. *Significantly (P<0.05); NS, not significantly (P>0.05) different from the control value obtained in the absence of chenodeoxycholic acid. The data are the means±s.e.m. (n=3–5). The [Ca2+]i and force were expressed as a percentage, assigning the values in normal PSS and 60 mM K+ PSS to be 0 and 100%, respectively.

We also examined the effects of other receptor antagonists on the fMLP-induced contraction. The antagonists and the concentrations that we used were 10 μM atropine (muscarinic acetylcholine receptor), 1 μM [des-Arg10]-HOE 140 (bradykinin B1 receptor), 0.1 μM HOE 140 (bradykinin B2 receptor), 0.1 μM pyrilamine (histamine H1 receptor), 1 μM famotidine (histamine H2 receptor), 0.1 μM SR 140333 (tachykinin NK1 receptor), and 0.1 μM SR 48968 (tachykinin NK2 receptor). All these antagonists had no significant effect on the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and force development (data not shown). In the guinea-pig T. coli, the contractions induced by carbachol, bradykinin, histamine, and substance P were significantly antagonized by 10 μM atropine, 0.1 μM HOE 140, 0.1 μM pyrilamine, and 0.1 μM SR 140333, respectively (data not shown).

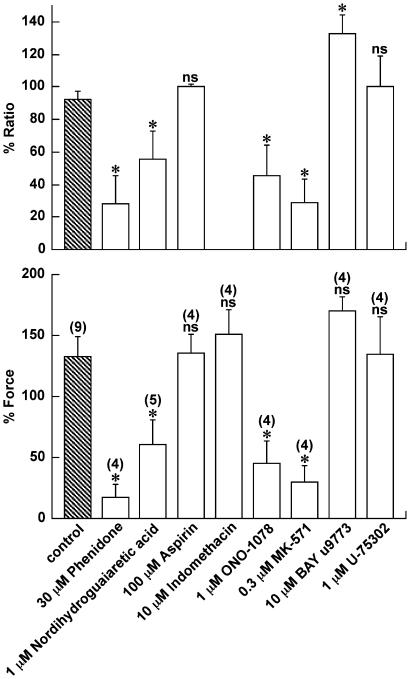

Involvement of lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid in the fMLP-induced contraction

The possible involvement of lipoxygenase or cyclooxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid in the fMLP-induced contraction was examined by using inhibitors of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase, and leukotriene receptor antagonists as shown in Figure 7. All inhibitors and antagonists were applied 10 min prior and during the contraction induced by 10 μM fMLP, and their effect was examined at the peak of the fMLP-induced contraction. The inhibition of both lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase by 30 μM phenidone significantly inhibited the fMLP-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i and force development (Figure 7). The inhibition of lipoxygenase by 1 μM nordihydroguaiaretic acid significantly inhibited the fMLP-induced contractile response. On the other hand, the inhibition of cyclooxygenase by 100 μM aspirin or 10 μM indomethacin had no significant effect on the fMLP-induced force development. Aspirin did not inhibit the fMLP-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i. Since indomethacin caused an artifact in fluorometry, its effect on [Ca2+]i was not evaluated (data not shown). In line with these observations, a nonselective leukotriene receptor antagonist, ONO-1078 (1 μM), significantly inhibited the fMLP-induced elevation of [Ca2+]i and force. A selective leukotriene Cys Lt1 antagonist, MK-571 (0.3 μM), also significantly inhibited the fMLP-induced contractile response. An antagonist with a higher affinity toward leukotriene receptor Cys Lt2 than Cys Lt1, BAY u9773 (10 μM), demonstrated no significant effect. A leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist, U-75302 (1 μM), demonstrated no significant effect. None of the inhibitors or antagonists at the indicated concentrations had any significant effect on the contractions induced by 60 mM K+ or 10 μM carbachol, while higher concentrations caused a nonspecific effect on these contractions (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Involvement of lipoxygenase metabolites in the fMLP-induced contraction in the guinea-pig T. coli. The effect of 30 μM phenidone, 1 μM nordihydroguaiaretic acid, 100 μM aspirin, 10 μM indomethacin, 1 μM ONO-1078, 0.3 μM MK-571, 10 μM BAY u9773, and 1 μM U-75302 on the fMLP-induced contraction were evaluated at the maximal elevation of [Ca2+]i and force. Note that the effect of indomethacin on [Ca2+]i was not evaluated because indomethacin caused an artifact in fluorescence studies. The levels of [Ca2+]i and force obtained at rest (in 5.9 mM K+, 2.5 mM Ca2+-containing normal PSS) and those obtained at the steady state of the 60 mM K+-induced contraction were assigned values of 0 and 100%, respectively. The data are the mean±s.e.m. of the number of experiment as indicated in parentheses. *Significantly (P<0.05); NS, not significantly (P>0.05) different from the control values.

Discussion

The contractile effect of fMLP on the smooth muscle has been reported in various tissues including guinea-pig ileum (Marasco et al., 1982), human bronchus (Armour et al., 1986), rabbit pulmonary artery (Crowell et al., 1989), human coronary artery (Keitoku et al., 1997), and guinea-pig renal pelvis (Maggi et al., 1992). We demonstrated that fMLP exerts a contractile effect by activating a formyl peptide receptor in the guinea-pig T. coli. This conclusion is based on the observation that chenodeoxycholic acid, a formyl peptide receptor antagonist, specifically abolished the fMLP-induced contraction in a dose-dependent manner but not the contraction induced by high K+ depolarization or carbachol. A receptor similar to that expressed in leukocyte has been suggested to be involved in the fMLP-induced contraction of the guinea-pig ileum (Marasco et al., 1982). However, the molecular identity of the receptor remains unknown. Among the identified receptor genes, human FPR and FPRL1 and mouse FPR1 and FPR-rs2 could serve as a functional receptor for fMLP (Le et al., 2002; Wang & Ye, 2002). fMLP binds to FPR with Kd value in the picomolar to low nanomolar range (high-affinity receptor), while it binds to FPRL1 with Kd value in micromolar range (low-affinity receptor) (Ye et al., 1992; Quehenberger et al., 1993). Chenodeoxycholic acid has been shown to act as a competitive antagonist of both FPR and FPRL1 at concentrations ⩽150 μM (Chen et al., 2000). In the present study, the nanomolar to micromolar concentrations of fMLP were required to induce a significant elevation of [Ca2+]i and force development, and chenodeoxycholic acid inhibited fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and force development at concentrations ⩽100 μM. We thus suggest that a low-affinity receptor similar to human FPRL1 is involved in the fMLP-induced contraction in the guinea-pig T. coli.

In the rabbit pulmonary artery, human bronchus, and guinea-pig airway, the cyclooxygenase and/or lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid such as thromboxane A2 and leukotriene C4 have been suggested to mediate the fMLP-induced contractile effects (Hamel et al., 1984; Armour et al., 1986; Shore et al., 1987; Crowell et al., 1989; Keitoku et al., 1997). In the present study, lipoxygenase metabolites but not cyclooxygenase metabolites are suggested to make a major contribution to fMLP-induced contraction. The observations with leukotriene receptor antagonists suggest that leukotriene receptor Cys Lt1, but not Cys Lt2 receptor or leukotriene B4 receptor, plays a major role in such fMLP-induced contraction. Leukotrienes such as D4 and C4 species are thus suggested to be major contractile mediators of the fMLP-induced contraction in the guinea-pig T. coli (Haeggstrom & Wetterholm, 2002; Izumi et al., 2002; Martel-Pelletier et al., 2003; Mazzetti et al., 2003).

These findings thus suggest that fMLP does not directly evoke contractile responses in the guinea-pig T. coli, but lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid such as leukotrienes mediate the fMLP-induced contraction. The indirect contractile effect of fMLP is consistent with the observation that the [Ca2+]i and force started to increase with a 30-s lag time after stimulation with fMLP. The indirect contractile mechanism has been reported in human airways, guinea-pig lung (Armour et al., 1986; Shore et al., 1987). However, it remains to be elucidated which type of cell is responsible for fMLP-induced production of lipoxygenase metabolites. The strips used in the present study contained smooth muscle cells and interstitial fibroblasts as major cellular components. Leukocytes have also been reported to be responsible for the fMLP-induced, leukotriene-mediated contraction in the human umbilical vein, canine coronary artery, and guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle (Strek et al., 1993; Minamino et al., 1996; Kerr et al., 1998). Either an autocrine or paracrine mechanism could thus be involved in the fMLP-induced contraction. It still remains to be determined as to which type of cell is the primary cell responding fMLP in the guinea-pig T. coli.

In the present study, the contractile mechanism was elucidated in terms of intracellular Ca2+ signal transduction, by simultaneously monitoring the changes in [Ca2+]i and force development and examining the effects of the depletion of the extracellular Ca2+, two Ca2+ entry blockers, and rho-kinase inhibitor on the fMLP-induced contraction. The major findings are as follows: (1) fMLP induced a greater contraction for a given elevation of [Ca2+]i than 60 mM K+ depolarization. (2) The fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and force development were completely abolished by the removal of extracellular Ca2+. We thus suggest that fMLP-induced contraction is mainly due to the activation of the Ca2+ influx and enhancement of Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus in the guinea-pig T. coli.

The intra- and extracellular Ca2+ pools are the major source of the [Ca2+]i elevation induced by receptor stimulation. We suggest that the intracellular Ca2+ store plays a negligible role in the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and force development, based on the following observations: first, the removal of the extracellular Ca2+ completely abolished the fMLP-induced contractile response. On the other hand, carbachol did induce a significant elevation of [Ca2+]i and force, thus suggesting the significant involvement of the intracellular Ca2+ pool in the carbachol-induced contraction. Second, the pretreatment with fMLP had no effect on the subsequent carbachol-induced, intracellular Ca2+ pool-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation, and force development. Furthermore, the initial abrupt rising phase of [Ca2+]i and force seen with carbachol-induced contraction was missing in the fMLP-induced contraction. Such an initial phase of [Ca2+]i elevation and force development was considered to be partly due to Ca2+ release from the intracellular pool and partly due to the Ca2+ influx from the extracellular pool, because the initial phase was substantially but not completely inhibited by removing the extracellular Ca2+ or by diltiazem. On the other hand, the Ca2+ influx activated by fMLP is mostly diltiazem sensitive, thus suggesting that the voltage-operated Ca2+ channels plays a major role in the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. In the guinea-pig T. coli, the elevation of [Ca2+]i induced by elevating the extracellular K+ reaches the maximal at 40 mM K+ and higher concentrations (data not shown). The activation of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx is thus considered to reach a maximal level at 60 mM K+. The stimulation with 10 μM fMLP during the 60 mM K+-induced contraction induced no further increase in [Ca2+]i (data not shown). This observation thus also supports the involvement of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ influx in the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. However, diltiazem did not completely inhibit the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation, SK&F 96365 partly but significantly inhibited it, and the combination of diltiazem and SK&F 96365 completely abolished the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. These findings suggest that the nonvoltage-operated Ca2+ channels are also involved; however, they only play a minor role in the fMLP-induced [Ca2+]i elevation. The major contribution of the Ca2+ influx mainly through the voltage-operated Ca2+ channels and partly through the nonvoltage-operated Ca2+ channels and the negligible contraction of store Ca2+ release to the fMLP-induced contraction is consistent with our previous observations in the leukotriene C4-mediated contraction (Ieiri et al., 2001), thus supporting the involvement of leukotrienes in the fMLP-induced contraction.

It is well established that receptor stimulation induces contraction not only by increasing [Ca2+]i but also enhancing the Ca2+ sensitivity of the smooth muscle contractile apparatus (Somlyo et al., 1999). Rho-kinase has been recently shown to play an important role in the enhancement of the Ca2+ sensitivity by inhibiting the dephosphorylation of myosin or by directly activating myosin phosphorylation (Amano et al., 1996; Kimura et al., 1996). However, the observation that a rho-kinase inhibitor, Y27632, had no significant effect on the fMLP-induced force development excludes a major contribution of rho-kinase to the fMLP-induced Ca2+-sensitizing effect. Many other kinases, including Zip or Zip-like kinase, integrin-linked kinase, and myotonic dystrophy protein kinase, have been shown to induce the Ca2+-independent phosphorylation of myosin light chain or inhibition of myosin phosphatase, and thus suggested to be involved in the enhancement of Ca2+ sensitization (Hirano et al., 2003). It is thus possible that fMLP activated the kinases other than rho-kinase and thereby enhanced the Ca2+ sensitivity. However, this possibility still remains to be confirmed. On the other hand, we reported that the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was not enhanced in the leukotriene C4-induced contraction (Ieiri et al., 2001), which is inconsistent with the observation in the present study that fMLP increased the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. Leukotriene C4 could not account for all contractile mediators involved in the fMLP-induced contraction.

Since fMLP is a synthetic analogue of the bacterial chemotactic peptide, the observed contractile effect of fMLP may be linked to the contractile abnormality associated with the inflammatory responses to a bacterial infection of the intestine. On the other hand, chenodeoxycholic acid is a bile product, which could serve as an endogenous fMLP receptor antagonist, and thus help to suppress these functional abnormalities related to the fMLP-induced contractile effect in infectious bowel disease.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the contractile effect of fMLP in the guinea-pig T. coli. Our findings suggest that this effect is mediated by a low-affinity formyl peptide receptor similar to human FPRL1 or mouse FPR1-rs2. However, fMLP is not suggested to induce directly a contractile response, but lipoxygenase metabolites and leukotriene receptor Cys Lt1 are suggested to mediate directly the contractile responses. The Ca2+ influx, mainly through the voltage-operated Ca2+ channels and partly through the nonvoltage-operated Ca2+ channels, and the enhancement of the Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus are the main intracellular mechanisms for fMLP-induced contraction. The Ca2+ mobilization from the intracellular store sites was suggested to play a negligible role in fMLP-induced contraction, while rho-kinase may not play any major role in it at all. The contractile effect mediated by the formyl peptide receptor expressed in the intestinal smooth muscle may therefore play an important role in the pathophysiology related to the acute inflammatory response to bacterial infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Brian Quinn for linguistic comments and help with the paper. This study was supported in part by the grant from the 21st Century COE Program and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Nos. 15590758 and 16590695) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- [Ca2+]o

extracellular Ca2+ concentration

- EGTA

ethyleneglycol-bis (β-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′,-tetraacetic acid

- fMLP

N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine

- PSS

physiological salt solution

References

- AMANO M., ITO M., KIMURA K., FUKATA Y., CHIHARA K., NAKANO T., MATSUURA Y., KAIBUCHI K. Phosphorylation and activation of myosin by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:20246–20249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARMOUR C.L., BLACK J.L., JOHNSON P.R., VINCENC K.S., BEREND N. Formyl peptide-induced contraction of human airways in vitro. J. Appl. Physiol. 1986;60:141–146. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAO L., GERARD N.P., EDDY R.L., JR, SHOWS T.B., GERARD C. Mapping of genes for the human C5a receptor (C5AR), human FMLP receptor (FPR), and two FMLP receptor homologue orphan receptors (FPRH1, FPRH2) to chromosome 19. Genomics. 1992;13:437–440. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90265-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECKER E.L., FOROUHAR F.A., GRUNNET M.L., BOULAY F., TARDIF M., BORMANN B.J., SODJA D., YE R.D., WOSKA J.R., MURPHY P.M. Broad immunocytochemical localization of the formyl peptide receptor in human organs, tissues, and cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;292:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s004410051042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUKILI M.A., BUREAU M., LAGENTE V., LEFORT J., LELLOUCH-TUBIANA A., MALANCHERE E., VARGAFTIG B.B. Pharmacological modulation of the effects of N-formyl-L-methionyl-L-leucyl-L-phenylalanine in guinea-pigs: involvement of the arachidonic acid cascade. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1986;89:349–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN X., YANG D., SHEN W., DONG H.F., WANG J.M., OPPENHEIMEIM J.J., HOWARD M.Z. Characterization of chenodeoxycholic acid as an endogenous antagonist of the G-coupled formyl peptide receptors. Inflamm. Res. 2000;49:744–755. doi: 10.1007/s000110050656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROWELL R.E., VAN EPPS D.E., REED W.P. Responses of isolated pulmonary arteries to synthetic peptide F-Met-Leu-Phe. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;257:H107–H112. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO J.L., CHEN H., FILIE J.D., KOZAK C.A., MURPHY P.M. Differential expansion of the N-formyl peptide receptor gene cluster in human and mouse. Genomics. 1998;51:270–276. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRONERT K., GEWIRTZ A., MADARA J.L., SERHAN C.N. Identification of a human enterocyte lipoxin A4 receptor that is regulated by interleukin (IL)-13 and interferon γ and inhibits tumor necrosis factor α-induced IL-8 release. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1285–1294. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAEGGSTROM J.Z., WETTERHOLM A. Enzymes and receptors in the leukotriene cascade. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:742–753. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8463-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMEL R., FORD-HUTCHINSON A.W., LORD A., CIRINO M. Bronchoconstriction induced by N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine in the guinea pig; involvement of arachidonic acid metabolites. Prostaglandins. 1984;28:43–56. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(84)90112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRANO K., DERKACH D.N., HIRANO M., NISHIMURA J., KANAIDE H. Protein kinase network in the regulation of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of smooth muscle myosin light chain. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2003;248:105–114. doi: 10.1023/a:1024180101032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRANO K., KANAIDE H., ABE S., NAKAMURA M. Effects of diltiazem on calcium concentrations in the cytosol and on force of contractions in porcine coronary arterial strips. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1990;101:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IEIRI S., NISHIMURA J., HIRANO K., SUITA S., KANAIDE H. The mechanism for the contraction induced by leukotriene C4 in guinea-pig Taenia coli. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;133:529–538. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZUMI T., YOKOMIZO T., OBINATA H., OGASAWARA H., SHIMIZU T. Leukotriene receptors: classification, gene expression, and signal transduction. J. Biochem. 2002;132:1–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KANAIDE H.Measurement of [Ca2+]i in smooth muscle strips using front-surface fluorimetry Methods in Molecular Biology 1999Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 269–277.ed. Lambert, D.G. pp [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEITOKU M., KOHZUKI M., KATOH H., FUNAKOSHI M., SUZUKI S., TAKEUCHI M., KARIBE A., HORIGUCHI S., WATANABE J., SATOH S., NOSE M., ABE K., OKAYAMA H., SHIRATO K. FMLP actions and its binding sites in isolated human coronary arteries. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1997;29:881–894. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KERR S.W., YU R., STEARNS C.D., HAYNES N.A., WINQUIST R.J. Characterization of the polymorphonuclear leukocyte-induced vasoconstriction in isolated human umbilical veins. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;287:640–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIMURA K., ITO M., AMANO M., CHIHARA K., FUKATA Y., NAKAFUKU M., YAMAMORI B., FENG J., NAKANO T., OKAWA K., IWAMATSU A., KAIBUCHI K. Regulation of myosin phosphatase by Rho and Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) Science. 1996;273:245–248. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LACY M., JONES J., WHITTEMORE S.R., HAVILAND D.L., WETSEL R.A., BARNUM S.R. Expression of the receptors for the C5a anaphylatoxin, interleukin-8 and FMLP by human astrocytes and microglia. J. Neuroimmunol. 1995;61:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00075-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LE Y., YANG Y., CUI Y., YAZAWA H., GONG W., QIU C., WANG J.M. Receptors for chemotactic formyl peptides as pharmacological targets. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LE Y.Y., HU J.Y., GONG W.H., SHEN W.P., LI B.Q., DUNLOP N.M., HALVERSON D.O., BLAIR D.G., WANG J.M. Expression of functional formyl peptide receptors by human astrocytoma cell lines. J. Neuroimmunol. 2000;111:102–108. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAGGI C.A., SANTICIOLI P., DEL BIANCO E., GIULIANI S. Local motor responses to bradykinin and bacterial chemotactic peptide formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (FMLP) in the guinea-pig isolated renal pelvis and ureter. J. Urol. 1992;148:1944–1950. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARASCO W.A., FANTONE J.C., WARD P.A. Spasmogenic activity of chemotactic N-formylated oligopeptides: identity of structure–function relationships for chemotactic and spasmogenic activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1982;79:7470–7473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARASCO W.A., PHAN S.H., KRUTZSCH H., SHOWELL H.J., FELTNER D.E., NAIRN R., BECKER E.L., WARD P.A. Purification and identification of formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine as the major peptide neutrophil chemotactic factor produced by Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:5430–5439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTEL-PELLETIER J., LAJEUNESSE D., REBOUL P., PELLETIER J.P. Therapeutic role of dual inhibitors of 5-LOX and COX, selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003;62:501–509. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.6.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAZZETTI L., FRANCHI-MICHELI S., NISTRI S., QUATTRONE S., SIMONE R., CIUFFI M., ZILLETTI L., FAILLI P. The ACh-induced contraction in rat aortas is mediated by the Cys Lt1 receptor via intracellular calcium mobilization in smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138:707–715. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCOY R., HAVILAND D.L., MOLMENTI E.P., ZIAMBARAS T., WETSEL R.A., PERLMUTTER D.H. N-formyl peptide and complement C5a receptors are expressed in liver cells and mediate hepatic acute phase gene regulation. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:207–217. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERRITT J.E., ARMSTRONG W.P., BENHAM C.D., HALLAM T.J., JACOB R., JAXA-CHAMIEC A., LEIGH B.K., MCCARTHY S.A., MOORES K.E., RINK T.J. SK&F 96365, a novel inhibitor of receptor-mediated calcium entry. Biochem. J. 1990;271:515–522. doi: 10.1042/bj2710515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINAMINO T., KITAKAZE M., NODE K., FUNAYA H., INOUE M., HORI M., KAMADA T. Adenosine inhibits leukocyte-induced vasoconstriction. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:H2622–H2628. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANARO M.A., MITOLO V. Cellular responses to FMLP challenging. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 1999;21:397–419. doi: 10.3109/08923979909007117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROSSNITZ E.R., YE R.D. The n-formyl peptide receptor – a model for the study of chemoattractant receptor structure and function. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997;74:73–102. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUEHENBERGER O., PROSSNITZ E.R., CAVANAGH S.L., COCHRANE C.G., YE R.D. Multiple domains of the N-formyl peptide receptor are required for high-affinity ligand binding. Construction and analysis of chimeric N-formyl peptide receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:18167–18175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFMANN E., CORCORAN B.A., WAHL S.M. N-formylmethionyl peptides as chemoattractants for leucocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1975a;72:1059–1062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFMANN E., SHOWELL H.V., CORCORAN B.A., WARD P.A., SMITH E., BECKER E.L. The isolation and partial characterization of neutrophil chemotactic factors from Escherichia coli. J. Immunol. 1975b;114:1831–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHORE S.A., STIMLER-GERARD N.P., SMITH E., DRAZEN J.M. A formyl peptide contracts guinea pig lung: role of arachidonic acid metabolites. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987;63:2450–2459. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.6.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOMLYO A.P., WU X., WALKER L.A., SOMLYO A.V. Pharmacomechanical coupling: the role of calcium, G-proteins, kinases and phosphatases. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;134:201–234. doi: 10.1007/3-540-64753-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOZZANI S., SALLUSTO F., LUINI W., ZHOU D., PIEMONTI L., ALLAVENA P., VAN DAMME J., VALITUTTI S., LANZAVECCHIA A., MANTOVANI A. Migration of dendritic cells in response to formyl peptides, C5a, and a distinct set of chemokines. J. Immunol. 1995;155:3292–3295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STREK M.E., WHITE S.R., HSIUE T.R., KULP G.V., WILLIAMS F.S., LEFF A.R. Effect of mode of activation of human eosinophils on tracheal smooth muscle contraction in guinea pigs. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;264:L475–L481. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.5.L475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UEHATA M., ISHIZAKI T., SATOH H., ONO T., KAWAHARA T., MORISHITA T., TAMAKAWA H., YAMAGAMI K., INUI J., MAEKAWA M., NARUMIYA S. Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature. 1997;389:990–994. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Z.G., YE R.D. Characterization of two new members of the formyl peptide receptor gene family from 129S6 mice. Gene. 2002;299:57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YE R.D., CAVANAGH S.L., QUEHENBERGER O., PROSSNITZ E.R., COCHRANE C.G. Isolation of a cDNA that encodes a novel granulocyte N-formyl peptide receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;184:582–589. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90629-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]