Abstract

Antidiabetic sulphonylureas can bind to various intracellular organelles including mitochondria. The aim of this study was to monitor the influence of antidiabetic sulphonylureas on membrane permeability in mitochondria isolated from rat skeletal muscle.

The effects of glibenclamide (and other sulphonylurea derivatives) on mitochondrial function were studied by measuring mitochondrial swelling, mitochondrial membrane potential, respiration rate and Ca2+ transport into mitochondria.

We observed that glibenclamide induced mitochondrial swelling (EC50=8.2±2.5 μM), decreased the mitochondrial membrane potential and evoked Ca2+ efflux from the mitochondrial matrix. These effects were blocked by 2 μM cyclosporin A, an inhibitor of the mitochondrial permeability transition.

Moreover, 30 μM glibenclamide accelerated the respiratory rate in the presence of glutamate/malate, substrates of complex I of the mitochondrial respiratory chain.

In conclusion, we postulate that the antidiabetic sulphonylureas activate the mitochondrial permeability transition in skeletal muscle by increasing its sensitivity to Ca2+.

Keywords: Mitochondria, skeletal muscle, sulphonylureas, glibenclamide, mitochondrial permeability transition

Introduction

Sulphonylureas have successfully been used as oral hypoglycaemic agents to treat noninsulin-dependent (type II) diabetes mellitus (Henquin, 1992). The family of antidiabetic sulphonylureas includes such compounds as glibenclamide, glipizide and tolbutamide. The primary therapeutic effect of these drugs, that is, an increase of insulin level in blood, results from the binding of sulphonylurea, in the nanomolar concentration range, to a high-affinity site in the plasma membrane of pancreatic beta cells. The sulphonylurea receptor (SUR) is a structural component of the beta-cell ATP-regulated K+ channel (KATP channel) (Gribble & Ashcroft, 2000). Binding of sulphonylureas to the SUR causes closure of KATP channels leading to membrane depolarization and further influx of Ca2+ through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. This initiates a chain of events leading to the exocytosis of insulin from pancreatic beta cells. A direct action of antidiabetic sulphonylureas on insulin granules may also be important in potentiation of the beta-cell exocytotic machinery (Renström et al., 2002).

Antidiabetic sulphonylureas exhibit a pleiotropic action not only on pancreatic beta cells, that is, the so-called extrapancreatic effect, at the liver, skeletal, heart and smooth muscle sites (Luzi & Pozza, 1997). Some of them are due to the presence of KATP channels and some other to low-affinity interaction of antidiabetic sulphonylureas with other enzymes (Gribble & Reimann, 2003). For example, glibenclamide, in micromolar concentration range, can affect glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (Szewczyk, 1997). Some of these extrapancreatic effects could support the hypoglycaemic action of long-term sulphonylurea administration.

Recently, new targets for antidiabetic sulphonylureas have been found in membranes of organelles such as mitochondria and zymogen- and insulin-containing granules (Szewczyk, 1997). Mitochondria are the target for both potassium channel inhibitors such as antidiabetic sulphonylureas (Szewczyk & Wojtczak, 2002) and potassium channel openers such as diazoxide or NS1619 (Szewczyk & Marban, 1999; Debska et al., 2003; Kicinska et al., 2004). A low-affinity SUR was identified in the inner mitochondrial membrane (mitochondrial sulphonylurea receptor (mitoSUR)) (Szewczyk et al., 1997b; 1999). The mitoSUR also interacts with other mitoKATP channel inhibitors such as quinine (Bednarczyk et al., 2004). The use of the sulphonylurea derivative [125I]glibenclamide leads to labelling of a 28 kDa protein in heart mitochondria (Szewczyk et al., 1997b). Recently, with the use of the fluorescent probe BODIPY-glibenclamide, a 64 kDa protein was labelled in brain mitochondria (Bajgar et al., 2001). Probably, the mitoSUR is a subunit of the mitochondrial ATP-regulated potassium channel (Inoue et al., 1991). A sulphonylurea-sensitive, ATP-regulated potassium channel (mitoKATP channel) was identified in liver mitochondria (Inoue et al., 1991). Later on, a similar channel was described in heart (Paucek et al., 1992) and brain mitochondria (Bajgar et al., 2001; Debska et al., 2001). The mitoKATP channel attracts attention due to its likely involvement in cytoprotective phenomena in cardiac (Garlid et al., 2003) and brain (Liu et al., 2003) tissues. Recently, the mitoKATP channel was found in skeletal muscle mitochondria (Debska et al., 2002) and human T-lymphocytes (Dahlem et al., 2004).

Opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP) causes mitochondrial permeability transition (Bernardi, 1999a). This enables diffusion of solutes of a molecular mass <1500 Da across the inner mitochondrial membrane. The opening of PTP is promoted by low mitochondrial membrane potential, intramitochondrial Ca2+, phosphate and carboxyatractyloside. The closed conformation of the PTP is stabilized by high mitochondrial membrane potential, cyclosporin A (CsA), ADP, H+ and bongkrekic acid (Bernardi, 1999a). Several cytotoxic compounds induce or lower the threshold for the onset of the mitochondrial permeability transition via a direct action on mitochondria. They include, for example, the antitumour drug lonidamine (Ravagnan et al., 1999) and salicylate (Oh et al., 2003). PTP in muscle cell mitochondria may be a target for the toxic action of various drugs (Bernardi, 1999b).

The aim of this study was to characterize the interaction of antidiabetic sulphonylureas such as glibenclamide with isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria. For this purpose, we studied the effects of glibenclamide on mitochondrial swelling, membrane potential, respiration and calcium ion uptake. We have shown that antidiabetic sulphonylureas are able to activate the CsA-sensitive mitochondrial permeability transition in skeletal muscle mitochondria from rats.

Methods

Isolation of rat skeletal muscle mitochondria

Rat skeletal muscle mitochondria were prepared as described previously (Wiśniewski et al., 1993). Albino Wistar rats weighting 250–350 g were killed by decapitation, and the quadriceps and soleus muscles (4–5 g of tissue) were rapidly removed and transferred into ice-cold isolation medium (180 mM KCl, 10 mM EDTA–Na2, pH 7.4). Muscles were minced with scissors, trimmed clean of visible fat and connective tissues, and placed in 30 ml of the isolation medium supplemented with trypsin (1 mg per 1 mg of tissue). After 30 min, the tissue was homogenized using a motor-driven teflon-glass Potter homogenizer, and centrifuged at 300 × g for 6 min. The supernatant was decanted and centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The final mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in medium containing 180 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4, at a protein concentration of 30–50 mg ml−1. All procedures were carried out at 4°C.

Mitochondrial swelling

The swelling was measured in a 1 ml cuvette of a Shimadzu spectrophotometer, as the decrease of light scattering at 540 nm (Fontaine et al., 1998) at room temperature in a medium containing 125 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2 (He et al., 2000) (medium A), and 10 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate as respiratory substrates. The concentration of mitochondria in the swelling experiments was 0.4–0.7 mg protein ml−1.

Mitochondrial membrane potential measurements

The measurements were made at room temperature in a 3-ml cuvette of a Shimadzu RF-5000 spectrofluorometer (Tokyo, Japan) using 8 μM safranine O, a membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent dye. The samples were excited at 495 nm and the fluorescence was registered at 584 nm. The measurements were performed in medium A or a medium containing 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Pi–Tris, 5 μM EGTA–Tris, 10 mM Tris–MOPS, pH 7.3 (Fontaine et al., 1998) (medium B). In all, 10 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate were used as respiratory substrates. The mitochondrial concentration corresponded to 0.3 mg protein ml−1.

Mitochondrial respiration

Mitochondrial oxygen consumption was measured at 25°C using a Clark-type electrode in a medium containing 125 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM KH2PO4, 50 μM EDTA, pH 7.2, and 10 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate as respiratory substrates. The concentration of mitochondria was 0.3 mg protein ml−1. For uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation, we used 100 μM 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP).

Extramitochondrial Ca2+ concentration measurements

The extramitochondrial Ca2+ concentration was measured at room temperature in a 1 ml cuvette of a Shimadzu spectrofluorimeter, using 1 μM Ca2+ fluorescent indicator Calcium Green 5N (Ichas et al., 1997) (excitation 488 nm, emission 530 nm) in medium A with 10 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate. Calibration of the signal was achieved by the addition of a known amount of Ca2+. The concentration of mitochondria was 0.5 mg protein ml−1.

Results

Antidiabetic sulphonylureas induce CsA-sensitive mitochondrial swelling

In skeletal muscle mitochondria, as in liver mitochondria, calcium ions are able to induce a permeability transition (Figure 1). Freshly isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria were incubated in K+-medium (medium A, see Methods). Figure 1 shows that addition of 15 or 50 μM Ca2+ induced a rapid decrease of absorbance at 540 nm. This effect is known to be induced by an increase of mitochondrial volume due to solute influx into the mitochondrial matrix. In the presence of 2 μM CsA, no changes of mitochondrial volume upon addition of 15 or 50 μM Ca2+ were observed. CsA sensitivity of Ca2+-induced mitochondrial swelling indicated that activation of PTP was involved.

Figure 1.

Effect of Ca2+ on skeletal muscle mitochondria swelling. Mitochondrial swelling was measured as a decrease of light scattering (in a.u.) at 540 nm. Induction of mitochondrial swelling occurred on addition of 15 or 50 μM CaCl2. In the presence of 2 μM CsA, activation of mitochondrial PTP upon addition of 50 μM CaCl2 was not observed.

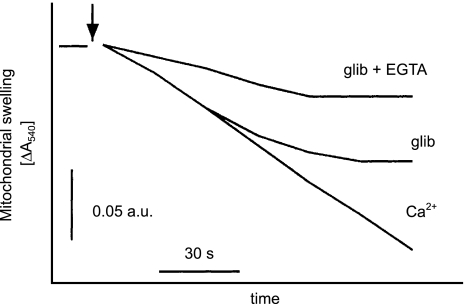

Application of 30 μM glibenclamide in K+-medium also induced mitochondrial swelling that could be inhibited by 2 μM CsA, as shown in Figure 2a. The effect of glibenclamide on mitochondrial swelling was dose dependent with EC50=8.2±2.5 μM (Figure 2b). The control level of mitochondrial swelling, during a 100 s incubation, increased from about 2.6±0.5 × 10−2 absorption units (a.u.) (n=8) to 8.3±0.6 × 10−2 a.u. (n=8) in the presence of 30 μM glibenclamide. As in previous observations, both the glibenclamide- and Ca2+-induced swelling was inhibited by 2 μM CsA (Figure 2c). The swelling induced by 30 μM glibenclamide was also diminished in the presence of 100 μM EGTA (Figure 3). A potassium channel opener, diazoxide, was without effect on mitochondrial swelling (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of glibenclamide on skeletal muscle mitochondrial swelling. (a) Effects of 30 μM glibenclamide on mitochondrial swelling in the absence and presence of 2 μM CsA. (b) Dose–response of glibenclamide-induced mitochondrial swelling. The results are expressed as means±s.d. (n=3). The amplitude of swelling induced by 30 μM glibenclamide was taken as 100%. (c) Effects of 30 μM glibenclamide (glib) on mitochondrial swelling in the absence and presence of 2 μM CsA and the effect of 50 μM CaCl2 in the presence of 2 μM CsA. Control indicates absorbance decrease in the absence of CaCl2. Data are means±s.d. of eight (control and glibenclamide) and three (CsA+glibenclamide and CsA+Ca2+) independent experiments. *Significantly different to control value with P<0.01.

Figure 3.

Effect of calcium chelators on glibenclamide-induced mitochondrial permeability transition. Mitochondrial swelling was monitored as described in legend to Figure 1. Effects of 30 μM glibenclamide on mitochondrial swelling are shown, in the absence and presence of 50 μM EGTA. The concentration of CaCl2 used to induce swelling was 50 μM.

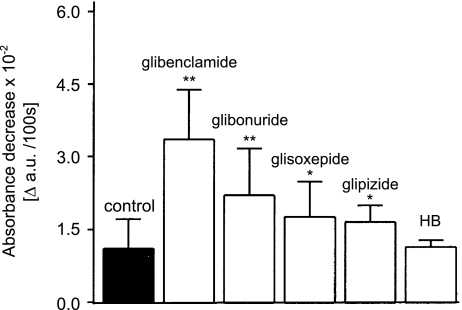

We also investigated the influence of other sulphonylurea derivatives on activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition (Figure 4). The largest effect was observed in the presence of 30 μM glibenclamide. Notably, an increase in mitochondrial swelling was also observed in the presence of glibonuride, glioxepide or glipizide. The sulphonylurea derivative HB180 at 30 μM was without effect on mitochondrial swelling (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of antidiabetic sulphonylurea derivatives on activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Glibenclamide, glibornuride, glisoxepide, glipizide and HB 180 were all used at a single concentration (30 μM). The results are expressed as means±s.d. of three independent experiments. *Significantly different to control value with P<0.01; **significantly different to control value with P<0.001.

Measurements of mitochondrial membrane potential

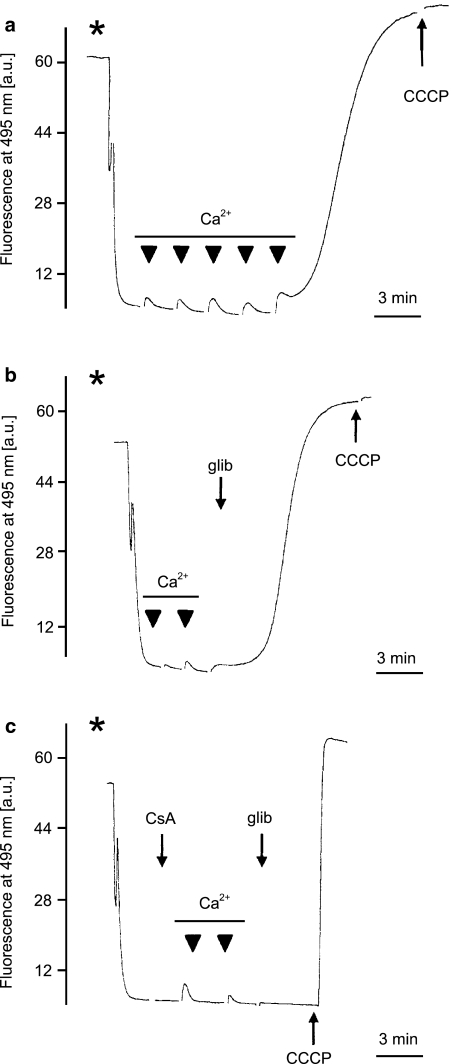

Experiments on mitochondrial swelling suggested that glibenclamide affects the integrity of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Hence, further experiments were focused on the effects of glibenclamide on mitochondrial membrane potential. Measurements of mitochondrial membrane potential were performed with the use of the potential sensitive fluorescent dye safranine O. They were performed in the presence of EGTA. Hence, induction of PTP required higher concentration of Ca2+ than in mitochondrial swelling experiments. After the addition of the mitochondria into the medium, the fluorescence of safranine O decreased due to accumulation of the dye in the mitochondrial matrix. First, we measured the mitochondrial membrane depolarization in the sucrose medium (n=5) (Figure 5). Additions of Ca2+ caused dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 5a), and in the presence of 30 μM glibenclamide, lower Ca2+ concentrations dissipated the potential (Figure 5b). In both cases, the effect was blocked by 2 μM CsA (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Effects of glibenclamide on the membrane potential of isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria in K+-free medium. (a) The mitochondrial membrane potential was measured as described in Methods. Depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane in medium B (see Methods) was induced by subsequent additions of Ca2+ at 50 μM in each pulse (black triangles). The asterisk indicates the addition of mitochondrial suspension (0.3 mg protein ml−1). Complete membrane depolarization was caused by the addition of carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) at 300 nM. (b) Effect of 30 μM glibenclamide (glib) on the mitochondrial membrane potential in the presence of Ca2+ at the same concentration as in (a). Complete membrane depolarization was caused by the addition of 300 nM CCCP. Additions of mitochondrial suspension and Ca2+ pulses are marked as in (a). (c) Effect of 30 μM glibenclamide (glib) on mitochondrial membrane potential in the presence of CsA at 2 μM and Ca2+ at the same concentration as in (b). Complete membrane depolarization was caused by the addition of 300 nM CCCP. Additions of mitochondrial suspension and Ca2+ pulses are marked as in (a).

In further experiments, we studied ion specificity of the effect of glibenclamide using K+-medium (n=6, medium A). The addition of 50 μM CaCl2 caused transient dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential due to the uptake of Ca2+ via the mitochondrial calcium uniporter (data not shown). Further additions of CaCl2 caused full depolarization of mitochondria due to the permeability transition. In the presence of 30 μM glibenclamide, lower Ca2+ concentrations were able to fully dissipate the potential, whereas glibenclamide itself did not dissipate significantly the mitochondrial potential in this assay. As observed previously for the sucrose medium, the effect of Ca2+ on induction of the permeability transition in KCl medium was blocked by 2 μM CsA (data not shown).

Glibenclamide induces Ca2+ efflux via mitochondrial PTP

Figure 6a shows changes of Calcium Green 5N fluorescence, a fluorescent calcium ion indicator, after the addition of Ca2+. When the concentration of Ca2+ in the mitochondria was sufficiently high, activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition was observed (n=6). As a result, an increase of Calcium Green 5N fluorescence was observed due to Ca2+ efflux. This effect was blocked by 2 μM CsA (data not shown). In the presence of 30 μM glibenclamide, however, a lower Ca2+ concentration was sufficient to activate the mitochondrial permeability transition (Figure 6b). This effect was also blocked by 2 μM CsA (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Effects of glibenclamide on Ca2+ release from mitochondrial matrix. (a) The extramitochondrial concentration of Ca2+was measured as described in Methods. Induction of Ca2+ release from mitochondrial matrix by subsequent additions of Ca2+ at 50 μM in each pulse (black triangles). The asterisk indicates the addition of mitochondrial suspension (0.5 mg protein ml−1). Complete membrane depolarization was caused by the addition of 300 nM CCCP. (b) Effect of 30 μM glibenclamide (glib) on Ca2+ release from mitochondrial matrix caused by subsequent additions of Ca2+ at the same concentration as in (a). Complete membrane depolarization was caused by the addition of 300 nM CCCP. The additions of mitochondrial suspension and Ca2+ pulses are marked as in (a). (c) Effect of 30 μM glibenclamide (glib) on Ca2+ release from mitochondrial matrix, caused by subsequent additions of Ca2+ at the same concentration as in (b), in the presence of 2 μM CsA. Complete membrane depolarization was caused by the addition of 300 nM CCCP. The addition of mitochondrial suspension and Ca2+ pulses are marked as in (a).

Glibenclamide increases mitochondrial respiration

Moreover, some influence of glibenclamide on respiration of isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria was observed. Oxygen consumption of isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria was measured in the presence of 10 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate as respiratory substrates. As shown in Figure 7, the resting state respiration of mitochondria increased from 5.4±1.1 (n=3) to 8.7±2.8 (n=3) nmol O2 mg protein min−1 after the addition of 30 μM glibenclamide.

Figure 7.

Effects of glibenclamide on the respiration of isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria. (a) Mitochondrial oxygen consumption was measured as described in Methods. (b) Stimulation of mitochondrial respiration by glibenclamide. Results are shown as the means±s.d. of four independent experiments. *Significantly different from the control with P<0.01.

Discussion

Antidiabetic sulphonylureas exhibit a pleiotropic action outside the pancreatic beta cell (Gribble & Ashcroft, 2000; Gribble & Reimann, 2003). A part of the observed effects is connected with sulphonylurea-sensitive KATP channels present in the plasma membrane of various cells, including smooth, cardiac and skeletal muscle cells, and in neurons (Rendell, 2004). Some of the effects of sulphonylureas are manifested in the cell interior by interaction of these drugs with mitochondria, nucleus or zymogen granules (Szewczyk, 1997; Soria et al., 2004). Mitochondria are unique cellular organelles that can build up a transmembrane electric potential of up to 180 mV, negative inside mitochondria (Nicholls & Ferguson, 2002). As a consequence, they can accumulate membrane-permeable compounds of cationic character such as glibenclamide, leading to its local high concentration exceeding the therapeutic range.

In this study, we investigated the effects of antidiabetic sulphonylureas on the integrity of skeletal muscle mitochondria. The main finding of this report is that antidiabetic sulphonylureas such as glibenclamide activate the CsA-sensitive mitochondrial permeability transition, by increasing its sensitivity to Ca2+.

Activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition results in matrix volume increase, outer membrane rupture and release of proapoptotic intermembrane space signalling molecules such as cytochrome c (Smaili et al., 2000). The mitochondrial permeability transition is Ca2+ dependent and CsA sensitive and leads to a collapse of ionic gradients and ultimately to mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondrial PTP activation is associated with both apoptosis by the mitochondrial pathway and necrosis due to a damage of mitochondria.

As with mitochondria from other tissues, PTPs can be induced in mitochondria from skeletal muscle (Fontaine et al., 1998). We observed that glibenclamide and other antidiabetic sulphonylureas such as glibonuride or glisoxepide induce the mitochondrial PTP. This process was accompanied by a loss of the mitochondrial potential and release of calcium ions from the mitochondrial matrix.

It has been shown recently that glibenclamide inhibits the skeletal muscle mitoKATP channel (Debska et al., 2002). This could suggest that there is some functional coupling between the stimulation of PTP by glibenclamide and the mitoKATP channel activity (Di Lisa et al., 2003). For example, it was shown that activation of the mitoKATP channel leads to depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential and prevents calcium overload in mitochondria (Holmuhamedov et al., 1999). Slight depolarization was also observed upon application of potassium channel openers, diazoxide or nicorandil, in skeletal muscle mitochondria (Debska et al., 2002). Our results suggest that the glibenclamide effect on PTP activation was not a consequence of mitoKATP blockade. First, we have demonstrated that the observed effects were independent of the presence of potassium ions in the experimental medium. Second, the potassium channel opener, diazoxide, was without effect on PTP activation. Hence, our results suggest that glibenclamide action is likely to proceed via sensitization of the PTP to calcium ions. A similar mechanism was observed for yessotoxin, a shellfish biotoxin acting as a potent inducer of the permeability transition in isolated mitochondria and intact cells (Bianchi et al., 2004). The requirement for a low matrix calcium concentration, by itself unable to activate the PTP, to allow the action of PTP-inducing drugs was recognized previously (Bernardi et al., 1993; Scorrano et al., 1997).

It is important to mention that, due to the hydrophobicity of its protonated form, glibenclamide is able to increase proton conductance of the mitochondrial membrane (Szewczyk et al., 1997a). In fact, we observed an increase of respiration of skeletal muscle mitochondria upon application of glibenclamide. Moreover, increased sensitivity of PTP opening to the rate of electron flow through respiratory chain complex I was reported previously (Fontaine et al., 1998). Hence, this effect can contribute to glibenclamide-induced permeability transition observed in our report. Recently, a new mechanism of the mitochondrial permeability induced by glibenclamide was reported (Fernandes et al., 2004). It was proposed that, in liver mitochondria, glibenclamide stimulates Cl− transport through the inner mitochondrial membrane by opening the inner mitochondrial anion channel followed by K+ entry (Fernandes et al., 2004).

PTP activation plays an important role in cell death pathways. Hence, the effects of antidiabetic sulphonylureas reported here may contribute to the overall action of these drugs leading to cell death, for example, by inhibition of the cytoprotective action of potassium channel openers (Szewczyk & Marban, 1999).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Research and Informatics Grant No. 3P04A05025. We are grateful to Professor Lech Wojtczak for comments on this paper.

Abbreviations

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone

- CsA

cyclosporin A

- DNP

2,4-dinitrophenol

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis (β-amino-ethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- mitoSUR

mitochondrial sulphonylurea receptor

- PTP

permeability transition pore

- SUR

sulphonylurea receptor

References

- BAJGAR R., SEETHARAMAN S., KOWALTOWSKI A.J., GARLID K.D., PAUCEK P. Identification and properties of a novel intracellular (mitochondrial) ATP-sensitive potassium channel in brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:33369–33374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEDNARCZYK P., KICINSKA A., KOMINKOVA V., ONDRIAS K., DOLOWY K., SZEWCZYK A. Quinine inhibits mitochondrial ATP-regulated potassium channel from bovine heart. J. Membr. Biol. 2004;199:63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNARDI P. Mitochondrial transport of cations: channels, exchangers, and permeability transition. Physiol. Rev. 1999a;79:1127–1155. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNARDI P. Mitochondria in muscle cell death. Ital. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999b;20:395–400. doi: 10.1007/s100720050057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNARDI P., VERONESE P., PETRONILLI V. Modulation of the mitochondrial cyclosporine A-sensitive permeability transition pore: I. Evidence for two separate Me2+ binding sites with opposing effects on the pore open probability. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:1005–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIANCHI C., FATO R., ANGELIN A., TROMBETTI F., VENTRELLA V., BORGATTI A.R., FATTORUSSO E., CIMINIELLO P., BERNARDI P., LENAZ G., CASTELLI P.A. Yessotoxin, a shellfish biotoxin, is a potent inducer of the permeability transition in isolated mitochondria and intact cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1656:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAHLEM Y.A., HORN T.F.W., BUNTINAS L., GONOI T., WOLF G., SIEMEN D. The human mitochondrial KATP channel is modulated by calcium and nitric oxide: a patch-clamp approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1656:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEBSKA G., KICINSKA A., DOBRUCKI J., DWORAKOWSKA B., NUROWSKA E., SKALSKA J., DOLOWY K., SZEWCZYK A. Large-conductance K+ channel openers NS1619 and NS004 as inhibitors of mitochondrial function in glioma cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;65:1827–1834. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEBSKA G., KICINSKA A., SKALSKA J., SZEWCZYK A., MAY R., ELGER C.E., KUNZ W.S. Opening of potassium channels modulates mitochondrial function in rat skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1556:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEBSKA G., MAY R., KICINSKA A., SZEWCZYK A., ELGER C.E., KUNZ W.S. Potassium channel openers depolarize hippocampal mitochondria. Brain Res. 2001;892:42–50. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI LISA F., CANTON M., MENABO R., DODONI G., BERNARDI P. Mitochondria and reperfusion injury – the role of permeability transition. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2003;98:235–241. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0415-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDES M.A.S., SANTOS M.S., MORENO J.M., DUBURS G., OLIVEIRA C.R., VICENTE A.F. Glibenclamide interferes with mitochondrial bioenergetics by inducing changes on membrane ion permeability. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2004;18:162–169. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FONTAINE E., ERIKSSON O., ICHAS F., BERNARDI P. Regulation of the permeability transition pore in skeletal muscle mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:12662–12668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARLID K.D., DOS SANTOS P., XIE Z.J., COSTA A.D., PAUCEK P. Mitochondrial potassium transport: the role of the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channel in cardiac function and cardioprotection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1606:1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(03)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIBBLE F.M., ASHCROFT F.M. Sulfonylurea sensitivity of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels from beta cells and extrapancreatic tissues. Metabolism. 2000;49 Suppl 2:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIBBLE F.M., REIMANN F. Sulphonylurea action revisited: the post-cloning era. Diabetologia. 2003;46:875–891. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HE L., POBLENZ A., MEDRONO C.J., FOX A. Lead and calcium produce rod photoreceptor cell apoptosis by opening the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:12175–12184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENQUIN J.C. The fiftieth anniversary of hypoglycaemic sulphonamides. How did the mother compound work. Diabetologia. 1992;35:907–912. doi: 10.1007/BF00401417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLMUHAMEDOV E.L., WANG L., TERZIC A.ATP-sensitive K+ channel openers prevent Ca2+ overload in cardiac mitochondria J. Physiol. 1999519347–360.Part 2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICHAS F., JOUAVILLE L.S., MOZART J.P. Mitochondria are excitable organelles capable of generating and conveying electrical and calcium signals. Cell. 1997;89:1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INOUE I., NAGASE H., KISHI K., HIGUTI T. ATP-sensitive K+ channel in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Nature. 1991;352:244–247. doi: 10.1038/352244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KICINSKA A., SKALSKA J., SZEWCZYK A. Mitochondria and big-conductance potassium channel openers. Toxicol. Mech. Methods. 2004;14:63–65. doi: 10.1080/15376520490257491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU D., SLEVIN J.R., LU C., CHAN S.L., HANSSON M., ELMER E., MATTSON M.P. Involvement of mitochondrial K+ release and cellular efflux in ischemic and apoptotic neuronal death. J. Neurochem. 2003;86:966–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUZI L., POZZA G. Glibenclamide: an old drug with a novel mechanism of action. Acta Diabetol. 1997;34:239–244. doi: 10.1007/s005920050081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHOLLS D.G., FERGUSON S.J. Bioenergetics 3. Boston, Amsterdam, London: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- OH K.W., QIAN T., BRENNER D.A., LEMASTER J.J. Salicylate enhances necrosis and apoptosis mediated by the mitochondrial permeability transition. Toxicol. Sci. 2003;73:44–52. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAUCEK P., MIRONOVA G., MAHDI F., BEAVIS A.D., WOLDEGIORGIS G., GARLID K.D. Reconstitution and partial purification of the glibenclamide-sensitive, ATP-dependent K+ channel from rat liver and beef heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:26062–26069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAVAGNAN L., MARZO I., COSTANTINI P., SUSIN S.A., ZAMZAMI N., PETTIT P.X., HIRSCH F., GOULBERN M., POUPON M.F., MICCOLI L., XIE Z., REED J.C., KROEMER G. Lonidamine triggers apoptosis via a direct, Bcl-2-inhibited effect on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Oncogene. 1999;18:2537–2546. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RENDELL M. The role of sulfonylureas in the management of the type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2004;64:1339–1358. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RENSTRÖM E., BARG S., THEVENOD F., RORSMAN P. Sulfonylurea-mediated stimulation of insulin exocytosis via an ATP-sensitive K+ channel-independent action. Diabetes. 2002;51 Suppl 1:S33–S36. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.2007.s33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCORRANO L., PETRONILLI V., BERNARDI P. On the voltage dependence of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. A critical appraisal. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:12295–12299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.19.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMAILI S.S., HSU Y.T., YOULE R.J., RUSSELL J.T. Mitochondria in Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2000;32:35–46. doi: 10.1023/a:1005508311495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SORIA B., QUESADA I., ROPERO A.B., PERTUSA J.A., MARTIN F., NADAL A. Novel players in pancreatic islet signaling. Diabetes. 2004;53 Suppl 1:S86–S91. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZEWCZYK A. Intracellular targets for antidiabetic sulfonylureas and potassium channel openers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997;54:961–965. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZEWCZYK A., CZYZ A., NALECZ M.J. ATP-regulated potassium channel blocker, glibenclamide, uncouples mitochondria. Pol. J. Pharmacol. 1997a;49:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZEWCZYK A., MARBAN E. Mitochondria: a new target for K channel openers. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01301-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZEWCZYK A., WOJCIK G., LOBANOV N.A., NALECZ M.J. The mitochondrial sulfonylurea receptor: identification and characterization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997b;230:611–615. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.6023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZEWCZYK A., WOJCIK G., LOBANOV N.A., NALECZ M.J. Modification of the mitochondrial sulfonylurea receptor by thiol reagents. Biochem. Bipohys. Res. Commun. 1999;262:255–258. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZEWCZYK A., WOJTCZAK L. Mitochondria as pharmacological target. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:101–127. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIŚNIEWSKI E., KUNZ W.S., GELLERICH F.N. Phosphate affects the distribution of flux control among the enzymes of oxidative phosphorylation in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:9343–9346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]