Abstract

We analyzed the effects of the Janus kinase 3 (Jak3)-specific inhibitor WHI-P131 (4-(4′-hydroxyphenyl)-amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline) and the Jak3/Syk inhibitor WHI-P154 (4-(3′-bromo-4′-hydroxyphenyl)-amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline) on the antigen-induced activation of mast cells.

In the rat mast cell line RBL-2H3, both WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibited the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK).

The phosphorylation of Gab2, Akt and Vav was also inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154, indicating that these inhibitors suppress the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K).

In bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) from Jak3-deficient (Jak3−/−) mice, degranulation and activation of MAPKs were induced by the antigen in almost the same extent as in BMMCs from wild-type mice. In addition, the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of MAPKs were inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 in both groups of BMMCs, indicating that these compounds inhibit a certain step except for Jak3.

The antigen-induced increase in the activity of Fyn, a probable tyrosine kinase of Gab2, was also inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 in RBL-2H3 cells. In BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice, the antigen stimulation induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn, which was inhibited by WHI-P131, as well as in BMMCs from wild-type mice and in RBL-2H3 cells.

These findings suggest that Jak3 does not play a significant role in the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs, and that WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibit the PI3K pathway by preventing the antigen-induced activation of Fyn, thus inhibiting the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs in mast cells.

Keywords: Mast cells, WHI-P131, WHI-P154, p44/42 MAP kinase, p38 MAP kinase, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Fyn

Introduction

Mast cells contribute to inflammatory responses by releasing preformed mediators such as histamine and serine proteases, and generating eicosanoids and cytokines (Williams & Galli, 2000). The early signaling events in antigen-stimulated mast cells are initiated by the tyrosine kinases Lyn and Syk (Beaven & Metzger, 1993; Beaven & Ozawa, 1996). The aggregation of the IgE high-affinity receptor I (FcɛRI) induced by the antigen results in the tyrosine phosphorylation of the β- and γ-chains of FcɛRI by Lyn. The phosphorylation of these chains promotes the recruitment of Lyn and Syk to the β-chain and the γ-chain, respectively, resulting in the tyrosine phosphorylation of linker proteins such as linker for activation of T cells (LAT). Furthermore, the tyrosine kinase Fyn is required for mast cell degranulation (Parravicini et al., 2002). Fyn phosphorylates a linker protein Gab2 (Parravicini et al., 2002), and leads to the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) (Gu et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 2001). PI3K regulates the translocation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) (Buhl & Cambier, 1999; Varnai et al., 1999) to membrane, promoting the activation of Btk by Lyn/Syk (Rawlings et al., 1996; Baba et al., 2001). The activation of these tyrosine kinases induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of phospholipase (PL) Cγ (Li et al., 1992) and Vav (Hirasawa et al., 1995b). The former leads to the generation of inositol 1, 4, 5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol, which induce an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ level and the activation of protein kinase C, respectively. The latter activates low molecular weight G proteins such as Ras and Rac (Gulbins et al., 1994; Han et al., 1998; Abe et al., 2000), resulting in the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family. The activation of MAPKs in mast cells causes the release of arachidonic acid (Hirasawa et al., 1995a) and the production of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-4 (Hirasawa et al., 2000) and IL-13 (Hirasawa et al., 2003).

Janus kinase 3 (Jak3), a member of the Jak family of cytoplasmic nonreceptor tyrosine kinases, is selectively expressed in hematopoietic cells (Johnston et al., 1994; Witthuhn et al., 1994) and associates with the γc-chain of receptors for IL-2, 4, 7, 9, 15 and 21 (Chen et al., 1997; Asao et al., 2001). Jak3 mediates cytokine-induced responses by activating the cytoplasmic latent forms of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) via phosphorylation of a specific tyrosine residue near the SH2 domain (Leonard & O'Shea, 1998). In addition, Jak3 has been suggested to play important roles in the FcɛRI-mediated activation of mast cells (Malaviya & Uckun, 1999; Malaviya et al., 1999, 2000) and T-cell receptor-mediated activation of T cells (Tomita et al., 2001). In Jak3-deficient (Jak3−/−) mice, the anaphylactic reaction was impaired with defective immune responses (Malaviya & Uckun, 1999; Malaviya et al., 1999). Jak3 also plays roles in bacterial clearance and neutrophil recruitment to the sites of infection by regulating the release of tumor necrosis factor-α from mast cells (Malaviya et al., 2001). In addition, stimulation of the rat mast cell line RBL-2H3 with antigen induced the activation of Jak3 and the specific Jak3 inhibitor WHI-P131 (4-(4′-hydroxyphenyl)-amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline) (Sudbeck et al., 1999) inhibited the antigen-induced degranulation, production of tumor necrosis factor-α and increase in the cytosolic Ca2+ level without affecting the activation of Syk (Malaviya et al., 1999). However, the precise role of Jak3 in the antigen-triggered signaling events in mast cells remains to be clarified. In this study, we evaluated the effects of the specific Jak3 inhibitor WHI-P131 and the Jak3/Syk inhibitor WHI-P154 (4-(3′-bromo-4′-hydroxyphenyl)-amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline) (Ghosh et al., 1999) on the IgE/FcɛRI-mediated activation of RBL-2H3 cells and bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) from Jak3−/− mice and wild-type mice, and found that these inhibitors strongly suppressed the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs in mast cells via the Jak3-independent pathway.

Methods

Materials

Dinitrophenyl-human serum albumin (DNP-HSA) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Polyclonal antibodies for phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204) and phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.). Polyclonal antibodies for phospho-Akt (Ser473) and Akt were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.). Monoclonal antibody for phosphotyrosine (4G10) and polyclonal antibodies for p44/42 MAPK and Gab2 were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, U.S.A.). Polyclonal antibodies for phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK, Thr183/Tyr185), JNK2, p38 MAPK, Vav, Lyn, Syk, Fyn and actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.).

Culture and treatment of RBL-2H3 cells

Rat basophilic leukemia RBL-2H3 cells (Health Science Research Resources Bank, Osaka, Japan) were suspended at 5 × 105 cells ml−1 in Eagle's minimum essential medium (Nissui Seiyaku, Tokyo, Japan) containing 10% (v v−1) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, U.S.A.), 18 μg ml−1 of penicillin G potassium, 50 μg ml−1 of streptomycin sulfate and 0.5% (v v−1) conditioned medium of DNP-specific IgE-producing hybridoma (kindly supplied by Dr Kazutaka Maeyama, Ehime University, Ehime, Japan), and 0.4, 1 and 10 ml aliquots of the cell suspension were plated on 24-well cluster dishes (for degranulation), 12-well cluster dishes (for Western blotting) and 100-mm dishes (for immunoprecipitation) (Costar, Cambridge, MA, U.S.A.), respectively. After incubation for 20 h at 37°C, the cells were washed with PIPES buffer (25 mM PIPES, pH 7.2, 119 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 5.6 mM glucose, 0.4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 and 0.1% (w v−1) bovine serum albumin), and incubated in the same buffer in the presence or absence of WHI-P131or WHI-P154 for 15 min at 37°C. The cells were then incubated for a specified period in medium containing the antigen DNP-HSA (50 ng ml−1) in the presence or absence of the compounds. The compounds were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide and added to the buffer. The final concentration of the vehicle was adjusted to 0.1% (v v−1) in all groups.

Mice and genetic analysis

Jak3−/− mice were backcrossed to BALB/c mice (Charles River Japan, Inc., Kanagawa, Japan) for at least six generations (Park et al., 1995). The mice were treated in accordance with procedures approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tohoku University, Japan. The mice were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Ampdirect (Shimadzu, Co., Kyoto, Japan). The Jak3-specific primers used were 5′-CCAGACCAGCAGAGGGACTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAAAGCGAACAGCAGTAGGC-3′ (reverse) (Park et al., 1995) and the PCR conditions were as follows; 94°C for 5 min, 33 cycles for 94°C for 1 min, 57°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min 30 s, 72°C for 10 min, and soaked at 4°C.

Preparation and stimulation of BMMCs

A primary culture of BMMCs was prepared from 8- to 12-week-old littermate wild-type and Jak3−/− mice. Briefly, the mice were killed and bone marrow was flushed aseptically from the femurs and tibiae into RPMI 1640 medium (Nissui Seiyaku, Tokyo, Japan) containing 10% (v v−1) FBS, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 18 μg ml−1 of penicillin G potassium, 100 μg ml−1 of streptomycin sulfate and 20% (v v−1) of the conditioned medium of murine IL-3-expressing NIH 3T3 cells which had been transfected with MFG-mIL-3 as a source of IL-3. The nonadherent bone marrow cells were then maintained at 37°C in a fully humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at a density of 2–5 × 105 cells ml−1 in the same medium, with the semiweekly replacement of the conditioned medium with a fresh batch. BMMCs obtained after 4 weeks of culture were more than 98% mast cells, as determined by morphologic analysis, and BMMCs were used for the following experiment at 4–6 weeks of culture. To stimulate BMMCs, the cells (2 × 106 cells ml−1) were incubated for 5 h at 37°C in the same medium containing 0.5% (v v−1) conditioned medium of DNP-specific IgE-producing hybridoma. The cells were washed twice with PIPES buffer, resuspended at 2 × 106 cells ml−1 in the same buffer and seeded at 0.4, 1 and 2 ml into 24-well cluster dishes (for degranulation), 12-well cluster dishes (for Western blotting) and six-well cluster dishes (for RNA extraction) (Costar), respectively. The cells were then pretreated with WHI-P131 or WHI-P154 for 15 min at 37°C, and stimulated with DNP-HSA (50 ng ml−1) for a specified period.

RT–PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from BMMCs (4 × 106 cells) using a DNA/RNA extraction Kit (Viogene, Taipei, Taiwan). First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.) and random hexamer oligonucleotides (Invitrogen Co.), and then a 210 bp fragment of Jak3 cDNA was amplified by PCR as described above. The glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene (a housekeeping gene) was used as an internal control as described previously (Edamatsu et al., 1997).

Determination of degranulation

As an index of degranulation, the activity of hexosaminidase released in the buffer during 20 min after the stimulation and that in the cells was determined as described previously (Hirasawa et al., 1995a).

Western blot analysis

After the stimulation, the cells in a 12-well cluster dish were lysed in 0.075 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM PIPES, pH 8.0, 1% (v v−1) Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 2.5 mM pNPP, 1 mM Na3VO4, 20 μg ml−1 of leupeptin and 10% (v v−1) glycerol). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 × g and 4°C for 20 min and the supernatant was obtained. The proteins in this fraction were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher and Schuell, Dassel, Germany). The phosphorylation of p44/p42 MAPK, p38 MAPK, JNK1/2 and Akt was detected by immunoblotting using polyclonal antibodies for phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) and phospho-Akt (Ser473), respectively. After stripping the antibodies by heating for 30 min at 60°C in stripping buffer (60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.7, 70 mM SDS and 0.7% (v v−1) 2-mercaptoethanol), each kinase was reblotted with antibodies for p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK, JNK2 and Akt. The phosphorylation levels of MAPKs were analyzed densitometrically and normalized by the protein levels of the corresponding kinases. To compare the tyrosine kinase expression in BMMCs, the membranes were probed with antibodies for Lyn, Fyn and Syk, and actin was detected as a control.

Immunoprecipitation

To detect the tyrosine-phosphorylated Fyn, Gab2 and Vav, RBL-2H3 cells (5 × 106 cells) in a 100-mm dish or BMMCs (8 × 106 cells) in a 60-mm dish were lysed in 0.5 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer and the supernatant was obtained as described above. The proteins in the supernatant of the cell lysate were first immunoprecipitated with anti-Fyn polyclonal, anti-Gab2 polyclonal or anti-Vav polyclonal antibody and immunoblotted with anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (4G10). After stripping the antibodies as described above, each protein was reblotted with the antibodies used in the immunoprecipitation. The phosphorylation levels of Fyn, Gab2 and Vav were analyzed densitometrically and normalized by the protein levels of the corresponding molecules.

Determination of Fyn activity

The immunoprecipitated Fyn was incubated for 60 min at 37°C in 50 μl of assay buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate and 2 mM dithiothreitol) containing dephosphorylated α-casein (25 μg, Sigma Chemical Co.) and 10 μM 32P-ATP (74 kBq, Perkin Elmer). The phosphorylated casein was detected by autoradiography.

For determination of direct actions of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on Fyn activity, purified Fyn from bovine thymus (5 U, Upstate Biotechnology) and dephosphorylated α-casein (25 μg) were incubated for 40 min at 37°C in the presence or absence of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154 in 50 μl of assay buffer containing 10 mM ATP. The phosphorylation of α-casein was detected by immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (4G10). Equal loading of α-casein in all lanes was confirmed by ponceau S staining.

Statistical analysis

Results of hexosaminidase release are expressed as means±s.e.m. of 3–4 culture dishes in one set of experiments. Comparisons of the results obtained were made with Dunnett's test. The results were confirmed with at least three independent sets of experiments.

Results

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of MAPKs in RBL-2H3 cells

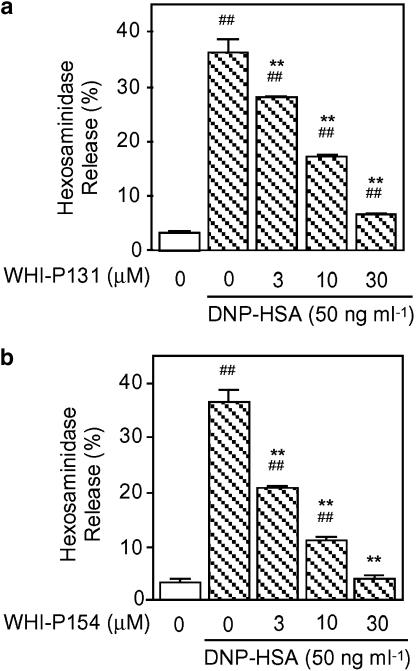

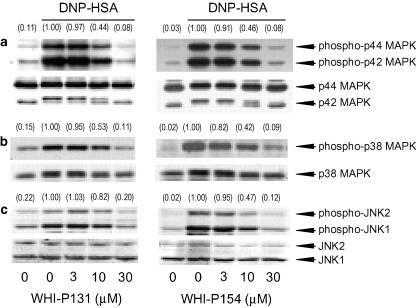

IgE-sensitized RBL-2H3 cells were stimulated by the antigen for 20 min, and hexosaminidase release was determined as an index of degranulation. The antigen-induced degranulation was inhibited by WHI-P131 (3, 10 and 30 μM) and WHI-P154 (3, 10 and 30 μM) in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1). The antigen-induced phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 determined 2, 20 and 40 min after the antigen stimulation, respectively, was also inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2). The finding that the Jak3 inhibitor WHI-P131 inhibited the degranulation and the phosphorylation of MAPKs as well as the Jak3/Syk inhibitor WHI-P154 suggested that these compounds inhibit some common target for the inhibition of degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs.

Figure 1.

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on DNP-HSA-induced hexosaminidase release. RBL-2H3 cells (2 × 105 cells) were incubated for 20 h at 37°C in 0.4 ml of medium containing IgE. After three washes, the cells were preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in PIPES buffer containing the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 (a) or WHI-P154 (b), and then stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 20 min in the continued presence of each drug. The activity of hexosaminidase released in the supernatant and that in the cells was determined to calculate hexosaminidase release (%). Vertical bars represent the s.e.m. from four wells. Statistical significance; ##P<0.01 vs corresponding unstimulated control, and **P <0.01 vs corresponding DNP-HSA-stimulated control.

Figure 2.

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on DNP-HSA-induced phosphorylation of MAPKs. RBL-2H3 cells (5 × 105 cells) were incubated for 20 h at 37°C in 1 ml of medium containing IgE. After three washes, the cells were preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in PIPES buffer containing the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154, and then stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 2 min (p44/42 MAPK, a), 20 min (p38 MAPK, b) and 40 min (JNK1/2, c) in the continued presence of each drug. The cell lysates were prepared and MAPKs and corresponding phosphorylated MAPKs were detected by Western blotting. Numbers in parentheses indicate the relative density ratio of the phospho-p44 MAPK, phospho-p38 MAPK and phospho-JNK2 to each of the corresponding protein as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of the DNP-HSA-stimulated control is set to 1.00.

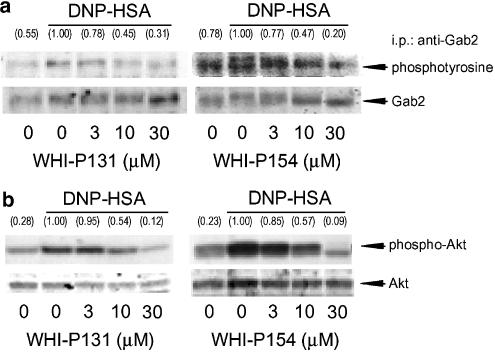

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on the antigen-induced phosphorylation of Gab2 and Akt in RBL-2H3 cells

The antigen stimulation increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2, an adaptor protein of PI3K, and the antigen-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2 was inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3a), suggesting that these compounds inhibited the step leading to the activation of PI3K. To confirm whether WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 reduce the activity of PI3K, the phosphorylation of Akt, an endogenous index of PI3K activity, was determined. The phosphorylation of Akt, which was analyzed by Western blotting with the antibody for phospho-Akt (Ser473), was increased by the antigen stimulation and was inhibited by these compounds in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3b). The inhibition of the tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2 by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 (Figure 3a) was correlated with the inhibition of Akt phosphorylation in the antigen-stimulated cells (Figure 3b), indicating that WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibited PI3K activation by inhibiting the tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2.

Figure 3.

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on DNP-HSA-induced phosphorylation of Gab2 and Akt. RBL-2H3 cells (5 × 106 or 5 × 105 cells) were incubated for 20 h at 37°C in 10 or 1 ml of medium containing IgE, respectively. After three washes, the cells were preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in PIPES buffer containing the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154, and then stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 2 min (tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2, a) and 20 min (phosphorylation of Akt, b) in the continued presence of each drug. The tyrosine phosphorylation of immunoprecipitated Gab2 and the serine phosphorylation of Akt were detected by Western blotting. Numbers in parentheses indicate the relative density ratio of the tyrosine-phosphorylated Gab2 and the phospho-Akt to each of the corresponding protein as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of the DNP-HSA-stimulated control is set to 1.00.

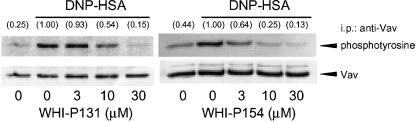

Inhibition of the antigen-induced phosphorylation of Vav by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 in RBL-2H3 cells

To analyze a potential link between the inhibition of PI3K activation by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 and the inhibition of activation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2, we examined the effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on the antigen-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav. The antigen stimulation increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav, which was inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 (Figure 4) in a concentration-dependent manner. Therefore, it was suggested that the inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav by these compounds (Figure 4) is correlated with the inhibition of the phosphorylation of Akt (Figure 3b), p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 (Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on DNP-HSA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav. RBL-2H3 cells (5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 20 h at 37°C in 10 ml of medium containing IgE. After three washes, the cells were preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in PIPES buffer containing the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154 and then stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 2 min in the continued presence of each drug. Vav was immunoprecipitated and the tyrosine phosphorylation of immunoprecipitated Vav was detected by Western blotting. Numbers in parentheses indicate the relative density ratio of the tyrosine-phosphorylated Vav to Vav protein as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of the DNP-HSA-stimulated control is set to 1.00.

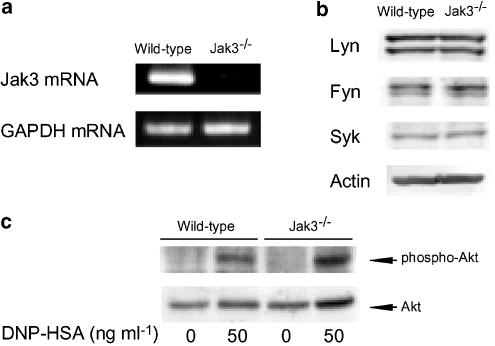

Comparisons of Jak3 mRNA level, tyrosine kinase expression and phosphorylation of Akt in BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice

To clarify whether Jak3 is involved in the antigen-induced activation of mast cells, we analyzed the antigen-induced activation of BMMCs prepared from Jak3−/− mice and wild-type mice. Firstly, to confirm the deficiency of Jak3 in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice, Jak3 mRNA was analyzed by RT–PCR. As shown in Figure 5a, Jak3 mRNA was not detected in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice, whereas the GAPDH mRNA level was equal to that in BMMCs from wild-type mice. In addition, there was no difference in the expression level of the tyrosine kinases, Lyn, Fyn and Syk in BMMCs between wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice (Figure 5b). The antigen-induced increase in the phosphorylation of Akt in BMMCs was also not significantly different between wild-type mice (3.2±0.7-fold increase, the means±s.e.m. from four independent experiments) and Jak3−/− mice (3.0±0.9-fold increase), as shown in Figure 5c. These findings indicate that the antigen-induced initial signaling pathway leading to the activation of PI3K is not defected in BMMCs prepared from Jak3−/− mice.

Figure 5.

Comparisons of Jak3 mRNA level, tyrosine kinase expression and phosphorylation of Akt in BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice. BMMCs (2 × 106 cells) prepared from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice were incubated for 5 h at 37°C in 1 ml of medium containing IgE. (a) After two washes, total mRNA was extracted and the expression of Jak3 mRNA and GAPDH mRNA was examined by RT–PCR. (b) BMMCs were lysed and tyrosine kinases and actin were detected by Western blotting. (c) IgE-sensitized BMMCs were resuspended in PIPES buffer and were stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 5 min for the detection of the phosphorylation of Akt. The cells were then lysed and Western blotting was performed.

Comparisons of time course changes in the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice

Consistent with the results in RBL-2H3 cells (Figures 1 and 2), the antigen stimulation induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice (Figure 6). The degranulation attained to a plateau 5 min after the antigen stimulation (Figure 6a), and the maximum inductions of phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK (Figure 6b), p38 MAPK (Figure 6c) and JNK1/2 (Figure 6d) were observed at 1, 5 and 10 min, respectively. Between BMMCs derived from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice, there was no difference in the time changes in the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK, p38 MAPK and JNK1/2. These findings indicate that Jak3 does not play significant roles in the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMMCs.

Figure 6.

Comparison of time changes in DNP-HSA-induced hexosaminidase release and phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice. (a) BMMCs (8 × 105 cells) prepared from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice were incubated for 5 h at 37°C in 0.4 ml of medium containing IgE. After two washes, the cells were resuspended in PIPES buffer and stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for the periods indicated. The activity of hexosaminidase released in the supernatant and that in the cells was determined to calculate hexosaminidase release (%). Vertical bars represent the s.e.m. from four wells. Statistical significance; ##P <0.01 vs corresponding unstimulated control. (b–d) BMMCs (2 × 106 cells) prepared from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice were incubated for 5 h at 37°C in 1 ml of medium containing IgE. After two washes, the cells were resuspended in PIPES buffer and stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for the periods indicated. The cells were lysed and the phosphorylation of each MAPK was detected by Western blotting.

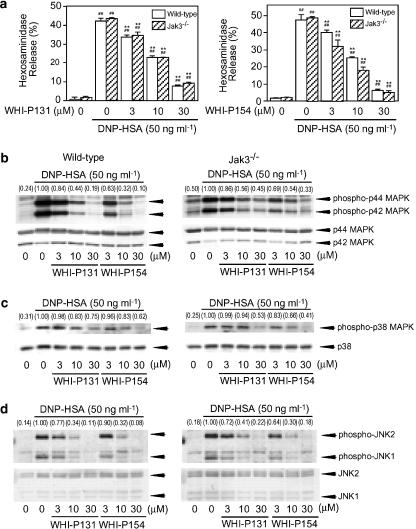

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice

To clarify whether WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibit the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of MAPKs by inhibiting Jak3, effects of these compounds on the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of MAPKs in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice were compared with those in BMMCs from wild-type mice. The antigen-induced degranulation (Figure 7a) and phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK (Figure 7b), p38 MAPK (Figure 7c) and JNK1/2 (Figure 7d) in Jak3−/− BMMCs were inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 in a concentration-dependent manner as in BMMCs from the wild-type mice (Figure 7a–d). These findings indicate that WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 suppress the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs by inhibiting a certain step except for Jak3.

Figure 7.

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on DNP-HSA-induced hexosaminidase release and phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice. (a) BMMCs (8 × 105 cells) prepared from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice were incubated for 5 h at 37°C in 0.4 ml of medium containing IgE. After two washes, the cells were resuspended in PIPES buffer and preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154. The cells were then stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 20 min in the continued presence of each drug. The activity of hexosaminidase released in the supernatant and that in the cells was determined to calculate hexosaminidase release (%). Vertical bars represent the s.e.m. from three wells. Statistical significance;##P<0.01 vs corresponding unstimulated control, and **P<0.01 vs corresponding DNP-HSA-stimulated control. (b–d) BMMCs (2 × 106 cells) prepared from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice were incubated for 5 h in 1 ml of medium containing IgE. After two washes, the cells were resuspended in PIPES buffer and preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154. The cells were then stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 2 min (p44/42 MAPK, b), 5 min (p38 MAPK, c) and 10 min (JNK1/2, d) in the continued presence of each drug. The cells were lysed and the phosphorylation of each MAPK was detected by Western blotting. Numbers in parentheses indicate the relative density ratio of the phospho-p44 MAPK, phospho-p38 MAPK and phospho-JNK2 to each of the corresponding protein as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of the DNP-HSA-stimulated control is set to 1.00.

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on the antigen-induced activation of Fyn

Since WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibited the tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2 in RBL-2H3 cells (Figure 3a), effects of these compounds on the activation of Fyn, which phosphorylates Gab2, were examined. The kinase activity of the immunoprecipitated Fyn was determined using α-casein as a substrate. As shown in Figure 8a, the phosphorylation of α-casein by the immunoprecipitated Fyn was increased by the antigen stimulation, and WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibited the antigen-induced increase in the kinase activity of Fyn. Furthermore, the antigen stimulation increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn, and the increase in the antigen-induced phosphorylation of Fyn was inhibited by WHI-P131 (Figure 8b). Then, we examined whether WHI-P131 inhibits the tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn by inhibiting Jak3. In both BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice, the antigen stimulation induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn (Figure 8c). Consistent with the effects of WHI-P131 on the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of MAPKs (Figure 7), WHI-P131 inhibited the antigen-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn even in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice (Figure 8c). These findings indicate that the inhibition of the antigen-induced activation of Fyn by WHI-P131 is not due to the inhibition of Jak3. Finally, we examined whether WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 directly inhibit the activity of Fyn. The purified Fyn from bovine thymus was incubated with α-casein in the presence of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154. As shown in Figure 8d, the kinase activity of the purified Fyn was not affected at 3 and 10 μM but was reduced at 30 μM of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154. Therefore, the direct inhibition of Fyn by WHI-P131 or WHI-P154 at 30 μM might be participated, in part, in the inhibition of phosphorylation of Gab2 by these compounds. Our findings suggest that WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibit the antigen-induced activation of Fyn by inhibiting certain kinase(s) other than Jak3 and Fyn.

Figure 8.

Effects of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 on DNP-HSA-induced phosphorylation and activity of Fyn. (a) RBL-2H3 cells (5 × 106 cells) were incubated for 20 h at 37°C in 10 ml of medium containing IgE. After three washes, the cells were preincubated for 15 min at 37°C in the presence of the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 or WHI-P154 and then stimulated with 50 ng ml−1 of DNP-HSA for 2 min. Fyn was immunoprecipitated and the immunoprecipitated Fyn was incubated for 60 min at 37°C in the assay buffer containing dephosphorylated α-casein (25 μg) and 32P-ATP (74 kBq). The phosphorylation of α-casein was detected by autoradiography and the relative density of phosphorylated α-casein was determined by densitometric analysis. The value of the DNP-HSA-stimulated control is set to 1.00. (b) Fyn was immunoprecipitated as described in (a). The tyrosine phosphorylation of the immunoprecipitated Fyn was detected by Western blotting. Numbers in parentheses indicate the density ratio of the phosphorylated Fyn to Fyn protein as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of the DNP-HSA-stimulated control is set to 1.00. (c) BMMCs (8 × 106 cells) prepared from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice were incubated for 5 h in 4 ml of medium containing IgE. The tyrosine phosphorylation of immunoprecipitated Fyn was determined as described in (b). (d) Fyn (5 U) was incubated for 40 min at 37°C in 50 μl of the assay buffer containing dephosphorylated α-casein (25 μg) in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154. The phosphorylation of α-casein was detected by Western blotting. Equal loading of α-casein in all lanes was confirmed by ponceau S staining. Numbers in parentheses indicate the relative density of phosphorylated casein as determined by densitometric analysis. The value of the ATP (+)-control is set to 1.00.

Discussion

Both the Jak3-specific inhibitor WHI-P131 and the Jak3/Syk inhibitor WHI-P154 (Ghosh et al., 1999; Sudbeck et al., 1999) inhibit the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of p44/42 MAPK (Malaviya & Uckun, 1999; Malaviya et al., 1999). In this study, we found that both WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibited the antigen-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 in addition to p44/42 MAPK (Figure 2). However, the findings that these compounds suppressed the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of MAPKs in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice as in BMMCs from wild-type mice (Figure 7) strongly suggest that the inhibition by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 of the FcɛRI-mediated activation of mast cells is not due to the inhibition of Jak3.

Since WHI-P131 inhibits the antigen-induced responses without affecting Syk activation (Malaviya et al., 1999), we focused on the effects of these compounds on the antigen-induced activation of PI3K, which is a Lyn/Syk-independent step (Parravicini et al., 2002). WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibited the antigen-induced phosphorylation of Akt, which is an index of PI3K activity (Figure 3b), indicating that these compounds block the antigen-induced activation of PI3K. The PI3K inhibitor wortmannin inhibits the antigen-induced degranulation (Hirasawa et al., 1997) and activation of p38 MAPK (Hirasawa et al., 2000) and JNK (Ishizuka et al., 1996) but not p44/42 MAPK (Ishizuka et al., 1996; Hirasawa et al., 2000). Therefore, it is suggested that the inhibition of the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 is due to the inhibition of the activation of PI3K, and the inhibition of the antigen-induced activation of p44/42 MAPK is due to another mechanism.

In mast cells, it is reported that the activation of PI3K is dependent on the association of PI3K with the adaptor protein Gab2 (Gu et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 2001). In addition, Gab2 is phosphorylated by Jak3 in IL-2-stimulated lymphocytes (Gadina et al., 2000) and by Fyn in the antigen-stimulated mast cells (Parravicini et al., 2002). We found that the antigen-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2 was inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 (Figure 3a), suggesting that the inhibition by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 of the antigen-induced activation of PI3K is due to the inhibition of the phosphorylation of Gab2. In Gab2-deficient mast cells, the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 but not p44/42 MAPK are impaired (Gu et al., 2001). Their findings support our notion that WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibit the antigen-induced degranulation and the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 by inhibiting the Gab2-PI3K pathway.

Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, a product of PI3K, enhances the tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav (Han et al., 1998), which leads to the activation of JNK1/2 in mast cells (Teramoto et al., 1997) and the activation of JNK1/2 and p38 MAPK in T cells (Hehner et al., 2000). Therefore, the PI3K-dependent activation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2 might be mediated by Vav. The antigen-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav in RBL-2H3 cells was inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 (Figure 4), indicating that these compounds inhibit the PI3K-Vav pathway, resulting in the inhibition of the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2. Furthermore, Malaviya et al. (1999) reported that WHI-P131 inhibits PLCγ activity in RBL-2H3 cells. PLCγ is directly phosphorylated by Btk in B cells (Takata & Kurosaki, 1996) and mast cells (Setoguchi et al., 1998), and the phosphorylation of PLCγ1 is regulated by PI3K (Barker et al., 1998) and Vav (Manetz et al., 2001). Thus, it is likely that the inhibition of PLCγ activation by WHI-P131 (Malaviya et al., 1999) is also due to the inhibition of the activation of PI3K and the phosphorylation of Vav.

Although Jak3 has been shown to play an important role in the FcɛRI-mediated activation of mast cells (Malaviya & Uckun, 1999; Malaviya et al., 1999, 2000), this role has not been well defined in Jak3−/− mast cells. Thus, we compared the antigen-induced responses of BMMCs from wild-type mice and Jak3−/− mice. We verified that Jak3 mRNA was not detectable in Jak3−/− BMMCs (Figure 5a). In addition, IL-4 enhances the proliferation and A23187-induced degranulation of BMMCs from wild-type mice but not of BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice (Suzuki et al., 2000), indicating that the function of Jak3 is completely defected in Jak3−/− mice. However, the time changes in the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of MAPKs in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice were similar to those in BMMCs from wild-type mice (Figure 6). Moreover, the antigen-induced passive cutaneous anaphylaxis as measured by Evans blue extravasation in the footpads in Jak3−/− mice was virtually the same as in wild-type mice (data not shown). These findings suggest that Jak3 does not play a critical role in the antigen-induced degranulation of mast cells. In contrast with our findings, Malaviya et al. (1999) reported that the antigen-induced degranulation of Jak3−/− BMMCs was less than that of wild-type BMMCs. One possible reason of this discrepancy is that some tyrosine kinase(s) might have compensated for the loss of Jak3 in the Jak3−/− BMMCs we used in this study. Although we confirmed that the expression of Lyn, Fyn and Syk in Jak3−/− BMMCs was similar to that in wild-type BMMCs (Figure 5b), we could not exclude the possibility that unidentified tyrosine kinases were upregulated by the loss of Jak3. Another possible reason is that the culture condition of BMMCs was different. Malaviya et al. (1999) used the conditioned medium of WEHI-3 cells as the source of growth factors of mast cells but we used that of 3T3 fibroblasts transfected with mouse IL-3 gene. It is possible that cytokines such as IL-4 and stem cell factor, which might exist in the conditioned medium, changed the Jak3-dependency in the antigen-induced degranulation of BMMCs. Malaviya & Uckun (1999) reported that the antigen-induced histamine release in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice was not completely impaired (about 55% of that in wild-type BMMCs). Therefore, it is unlikely that Jak3 is necessary for the antigen-induced degranulation. Taken together, we concluded that Jak3 does not play essential roles in the antigen-induced degranulation of mast cells. More importantly, the antigen-induced degranulation and phosphorylation of all MAPKs in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice were blocked by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 to the same level as in BMMCs from wild-type mice (Figure 7). These findings strongly indicate that the inhibition by both inhibitors of the antigen-induced responses is due to the inhibition of a certain step other than Jak3.

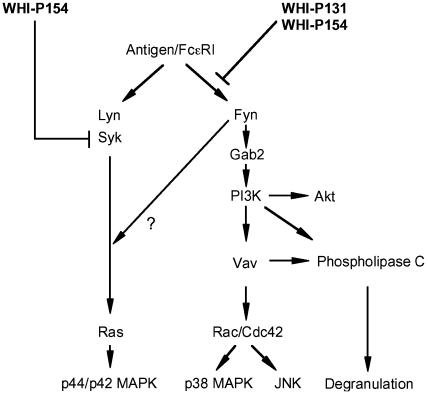

Recently, it has been disclosed that the tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2 and the activation of PI3K are regulated by Fyn, an Src family tyrosine kinase, but not by Lyn and Syk (Parravicini et al., 2002). This prompted us to examine the effects of both inhibitors on Fyn activation. We found that WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 reduced the kinase activity of Fyn (Figure 8a) in RBL-2H3 cells. WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 partially reduced the in vitro kinase activity of Fyn only at the highest concentration (30 μM) (Figure 8d), suggesting that these compounds inhibit the activation of Fyn more potently than its activity. The tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn is also independent on Jak3 because the antigen stimulation increased the tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn in BMMCs from Jak3−/− mice as well as in BMMCs from wild-type mice (Figure 8c). The findings that WHI-P131 inhibited the tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn in both BMMCs (Figure 8c), as well as in RBL-2H3 cells (Figure 8b), strongly support our notion that WHI-P131 inhibits a certain step except for Jak3. Taken together, our findings indicate that WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibit the activation of Fyn, resulting in the inhibition of the Gab2-PI3K pathway (Figure 9). On the other hand, the finding that the phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK was also inhibited by WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 suggested that Fyn might regulate the activation pathway of p44/42 MAPK in addition to the Gab2-P I3K pathway (Figure 9) as reported in T cells (Maulon et al., 2001). The molecular mechanisms by which WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibit the activation of Fyn remain to be elucidated.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the possible inhibitory mechanisms of WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 in the activation of mast cells.

We clarified that Jak3 plays a dispensable role in the FcɛRI-mediated activation of mast cells. However, its role in other signaling pathways cannot be completely excluded. Tomita et al. (2001) reported that Jak3 associates with the ς-chain of the T-cell receptor via the JH4 domain in T cells, whereas its association with the IL-2Rγ-chain is dependent on the JH7-6 domains of Jak3 (Chen et al., 1997). Therefore, it is possible that Jak3 binds to FcɛRI and modulates FcɛRI-mediated cytokine production via the phosphorylation of STATs. In addition, more recent studies have suggested that Jak3 plays a role in the expression of IL-10 in LPS-stimulated monocytes/macrophages (Kim et al., 2004). Thus, the role of Jak3 in another signaling pathway induced by FcɛRI-dependent or -independent stimulation in mast cells remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, both WHI-P131 and WHI-P154 inhibited the antigen-induced activation of mast cells via the Jak3-independent pathway (Figure 9). These compounds inhibited the activation of Fyn, resulting in inhibition of the Fyn-Gab2-PI3K pathway, which regulates the antigen-induced degranulation and activation of p38 MAPK and JNK1/2. The inhibition of p44/42 MAPK activation also occurs, in contrast, via the PI3K-independent pathway. Special attention should be paid when WHI-P131 is used as a specific inhibitor of Jak3.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Specific Research on Priority Areas (12139202) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Abbreviations

- BMMC

bone marrow-derived mast cell

- Btk

Bruton's tyrosine kinase

- DNP-HSA

dinitrophenyl-human serum albumin

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- FcɛRI

IgE high-affinity receptor I

- Jak

Janus kinase

- Jak3−/−

Jak3-deficient

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LAT

linker for activation of T cells

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PL

phospholipase

- STAT

signal transducers and activators of transcription

References

- ABE K., ROSSMAN K.L., LIU B., RITOLA K.D., CHIANG D., CAMPBELL S.L., BURRIDGE K., DER C.J. Vav2 is an activator of Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:10141–10149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASAO H., OKUYAMA C., KUMAKI S., ISHII N., TSUCHIYA S., FOSTER D., SUGAMURA K. The common γ-chain is an indispensable subunit of the IL-21 receptor complex. J. Immunol. 2001;167:1–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BABA Y., HASHIMOTO S., MATSUSHITA M., WATANABE D., KISHIMOTO T., KUROSAKI T., TSUKADA S. BLNK mediates Syk-dependent Btk activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:2582–2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARKER S.A., CALDWELL K.K., PFEIFFER J.R., WILSON B.S. Wortmannin-sensitive phosphorylation, translocation, and activation of PLCγ1, but not PLCγ2, in antigen-stimulated RBL-2H3 mast cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1998;9:483–496. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.2.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAVEN M.A., METZGER H. Signal transduction by Fc receptors: the FcɛRI case. Immunol. Today. 1993;14:222–226. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90167-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAVEN M.A., OZAWA K. Role of calcium, protein kinase C and MAP kinase in the activation of mast cells. Allergo. Int. 1996;45:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- BUHL A.M., CAMBIER J.C. Phosphorylation of CD19 Y484 and Y515, and linked activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, are required for B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of Bruton's tyrosine kinase. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4438–4446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN M., CHENG A., CHEN Y.Q., HYMEL A., HANSON E.P., KIMMEL L., MINAMI Y., TANIGUCHI T., CHANGELIAN P.S., O'SHEA J.J. The amino terminus of JAK3 is necessary and sufficient for binding to the common γ chain and confers the ability to transmit interleukin 2-mediated signals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:6910–6915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDAMATSU T., XIAO Y.Q., TANABE J., MUE S., OHUCHI K. Induction of neutrophil chemotactic factor production by staurosporine in rat peritoneal neutrophils. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:1651–1658. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GADINA M., SUDARSHAN S., VISCONTI R., ZHOU Y.J., GU H., NEEL B.G., O'SHEA J.J. The docking molecule gab2 is induced by lymphocyte activation and is involved in signaling by interleukin-2 and interleukin-15 but not other common γ chain-using cytokines. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:26959–26966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH S., ZHENG Y., JUN X., MAHAJAN S., MAO C., SUDBECK E.A., UCKUN F.M. Specificity of α-cyano-β-hydroxy-β-methyl-N-[4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenyl]-propenamide as an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:4264–4272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GU H., SAITO K., KLAMAN L.D., SHEN J., FLEMING T., WANG Y., PRATT J.C., LIN G., LIM B., KINET J.P., NEEL B.G. Essential role for Gab2 in the allergic response. Nature. 2001;412:186–190. doi: 10.1038/35084076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GULBINS E., COGGESHALL K.M., BAIER G., TELFORD D., LANGLET C., BAIER-BITTERLICH G., BONNEFOY-BERARD N., BURN P., WITTINGHOFER A., ALTMAN A. Direct stimulation of Vav guanine nucleotide exchange activity for Ras by phorbol esters and diglycerides. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:4749–4758. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN J., LUBY-PHELPS K., DAS B., SHU X., XIA Y., MOSTELLER R.D., KRISHNA U.M., FALCK J.R., WHITE M.A., BROEK D. Role of substrates and products of PI3-kinase in regulating activation of Rac-related guanosine triphosphatases by Vav. Science. 1998;279:558–560. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEHNER S.P., HOFMANN T.G., DIENZ O., DROGE W., SCHMITZ M.L. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Vav1 as a point of integration for T-cell receptor- and CD28-mediated activation of JNK, p38, and interleukin-2 transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:18160–18171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.24.18160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRASAWA N., IZUMI S., LINWONG W., OHUCHI K. Inhibition by dexamethasone of interleukin 13 production via glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of c-Jun phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2003;554:489–493. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRASAWA N., SANTINI F., BEAVEN M.A. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/cytosolic phospholipase A2 pathway in a rat mast cell line. Indications of different pathways for release of arachidonic acid and secretory granules. J. Immunol. 1995a;154:5391–5401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRASAWA N., SATO Y., FUJITA Y., OHUCHI K. Involvement of a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-p38 mitogen activated protein kinase pathway in antigen-induced IL-4 production in mast cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1456:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRASAWA N., SATO Y., YOMOGIDA S., MUE S., OHUCHI K. Role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in degranulation induced by IgE-dependent and -independent mechanisms in rat basophilic RBL-2H3 (m1) cells. Cell. Signal. 1997;9:305–310. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRASAWA N., SCHARENBERG A., YAMAMURA H., BEAVEN M.A., KINET J.P. A requirement for Syk in the activation of the microtubule-associated protein kinase/phospholipase A2 pathway by FcɛR1 is not shared by a G protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1995b;270:10960–10967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIZUKA T., OSHIBA A., SAKATA N., TERADA N., JOHNSON G.L., GELFAND E.W. Aggregation of the FcɛRI on mast cells stimulates c-Jun amino-terminal kinase activity. A response inhibited by wortmannin. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:12762–12766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSTON J.A., KAWAMURA M., KIRKEN R.A., CHEN Y.Q., BLAKE T.B., SHIBUYA K., ORTALDO J.R., MCVICAR D.W., O'SHEA J.J. Phosphorylation and activation of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in response to interleukin-2. Nature. 1994;370:151–153. doi: 10.1038/370151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM H.J., HART J., KNATZ N., HALL M.W., WEWERS M.D. Janus kinase 3 down-regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-1β-converting enzyme activation by autocrine IL-10. J. Immunol. 2004;172:4948–4955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEONARD W.J., O'SHEA J.J. JAKs and STATs: biological implications. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:293–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI W., DEANIN G.G., MARGOLIS B., SCHLESSINGER J., OLIVER J.M. FcɛR1-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins, including phospholipase Cγ1 and the receptor βγ2 complex, in RBL-2H3 rat basophilic leukemia cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:3176–3182. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALAVIYA R., CHEN C.L., NAVARA C., MALAVIYA R., LIU X.P., KEENAN M., WAURZYNIAK B., UCKUN F.M. Treatment of allergic asthma by targeting Janus kinase 3-dependent leukotriene synthesis in mast cells with 4-(3′,5′-dibromo-4′-hydroxyphenyl)amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline (WHI-P97) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:912–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALAVIYA R., NAVARA C., UCKUN F.M. Role of Janus kinase 3 in mast cell-mediated innate immunity against gram-negative bacteria. Immunity. 2001;15:313–321. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALAVIYA R., UCKUN F.M. Genetic and biochemical evidence for a critical role of Janus Kinase (JAK)-3 in mast cell-mediated type I hypersensitivity reactions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;257:807–813. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALAVIYA R., ZHU D., DIBIRDIK I., UCKUN F.M. Targeting Janus kinase 3 in mast cells prevents immediate hypersensitivity reactions and anaphylaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:27028–27038. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANETZ T.S., GONZALEZ-ESPINOSA C., ARUDCHANDRAN R., XIRASAGAR S., TYBULEWICZ V., RIVERA J. Vav1 regulates phospholipase Cγ activation and calcium responses in mast cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:3763–3774. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.11.3763-3774.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAULON L., MARI B., BERTOLOTTO C., RICCI J.E., LUCIANO F., BELHACENE N., DECKERT M., BAIER G., AUBERGER P. Differential requirements for ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK activation by thrombin in T cells. Role of p59 Fyn and PKCɛ. Oncogene. 2001;20:1964–1972. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK S.Y., SAIJO K., TAKAHASHI T., OSAWA M., ARASE H., HIRAYAMA N., MIYAKE K., NAKAUCHI H., SHIRASAWA T., SAITO T. Developmental defects of lymphoid cells in Jak3 kinase-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:771–782. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARRAVICINI V., GADINA M., KOVAROVA M., ODOM S., GONZALEZ-ESPINOSA C., FURUMOTO Y., SAITOH S., SAMELSON L.E., O'SHEA J.J., RIVERA J. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAWLINGS D.J., SCHARENBERG A.M., PARK H., WAHL M.I., LIN S., KATO R.M., FLUCKIGER A.C., WITTE O.N., KINET J.P. Activation of BTK by a phosphorylation mechanism initiated by SRC family kinases. Science. 1996;271:822–825. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SETOGUCHI R., KINASHI T., SAGARA H., HIROSAWA K., TAKATSU K. Defective degranulation and calcium mobilization of bone-marrow derived mast cells from Xid and Btk-deficient mice. Immunol. Lett. 1998;64:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUDBECK E.A., LIU X.P., NARLA R.K., MAHAJAN S., GHOSH S., MAO C., UCKUN F.M. Structure-based design of specific inhibitors of Janus kinase 3 as apoptosis-inducing antileukemic agents. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:1569–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUZUKI K., NAKAJIMA H., WATANABE N., KAGAMI S., SUTO A., SAITO Y., SAITO T., IWAMOTO I. Role of common cytokine receptor γ chain (γc)- and Jak3-dependent signaling in the proliferation and survival of murine mast cells. Blood. 2000;96:2172–2180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKATA M., KUROSAKI T. A role for Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cell antigen receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase Cγ2. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:31–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERAMOTO H., SALEM P., ROBBIN K.C., BUSTELO X.R., GUTKIND J.S. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the vav proto-oncogene product links FcɛRI to the Rac1-JNK pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:10751–10755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMITA K., SAIJO K., YAMASAKI S., IIDA T., NAKATSU F., ARASE H., OHNO H., SHIRASAWA T., KURIYAMA T., O'SHEA J.J., SAITO T. Cytokine-independent Jak3 activation upon T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation through direct association of Jak3 and the TCR complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:25378–25385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VARNAI P., ROTHER K.I., BALLA T. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent membrane association of the Bruton's tyrosine kinase pleckstrin homology domain visualized in single living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:10983–10989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS C.M., GALLI S.J. The diverse potential effector and immunoregulatory roles of mast cells in allergic disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000;105:847–859. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.106485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON B.S., PFEIFFER J.R., SURVILADZE Z., GAUDER E.A., OLIVER J.M. High resolution mapping of mast cell membranes reveals primary and secondary domains of FcɛRI and LAT. J. Cell Biol. 2001;154:645–658. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITTHUHN B.A., SILVENNOINEN O., MIURA O., LAI K.S., CWIK C., LIU E.T., IHLE J.N. Involvement of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in signalling by interleukins 2 and 4 in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Nature. 1994;370:153–157. doi: 10.1038/370153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]