Abstract

The purpose of the present study is to compare the capacity of opioid antagonists to elicit withdrawal jumping in mice following two acute pretreatment doses of the opioid agonist morphine. Antagonists that precipitate vigorous withdrawal jumping across both morphine treatment doses are hypothesized to be strong inverse agonists at the μ-opioid receptor, whereas antagonists that elicit withdrawal jumping in mice treated with the high but not the low dose of morphine are hypothesized to be weak inverse agonists.

Male, Swiss-Webster mice (15–30 g) were acutely treated with 56 or 180 mg kg−1 morphine 4 h prior to injection with naloxone, naltrexone, diprenorphine, nalorphine, or naloxonazine. Vertical jumping, paw tremors, and weight loss were recorded. Naloxone, naltrexone, and diprenorphine produced withdrawal jumping after 56 and 180 mg kg−1morphine pretreatment. Nalorphine and naloxonazine produced moderate withdrawal jumping after 180 mg kg−1 morphine pretreatment, but failed to elicit significant withdrawal jumping after 56 mg kg−1 morphine pretreatment. Nalorphine and naloxonazine blocked the withdrawal jumping produced by naloxone. All antagonists produced paw tremors and weight loss although these effects were generally not dose-dependent.

Taken together, these findings reveal a rank order of negative intrinsic efficacy for these opioid antagonists as follows: naloxone=naltrexone⩾diprenorphine>nalorphine=naloxonazine. Furthermore, the observation that nalorphine and naloxonazine blocked the naloxone-induced withdrawal jumping provides additional evidence that nalorphine and naloxonazine are weaker inverse agonists than naloxone.

Keywords: Acute dependence, diprenorphine, intrinsic efficacy, inverse agonist, mice, opioid withdrawal, nalorphine, naloxonazine, naloxone, naltrexone, withdrawal jumping

Introduction

Chronic morphine exposure has been postulated to produce a state of constitutively active μ-opioid receptors in a number of cell lines (Wang et al., 1994; 1999; 2000; Burford et al., 2000; Liu & Prather, 2001). These investigators suggest that chronic morphine exposure shifts the balance from normal, agonist-sensitive μ-opioid receptors to a greater proportion of constitutively active, agonist-independent μ-opioid receptors. The actions of this constitutively active μ-opioid receptor are balanced by concomitantly upregulated adenylate cyclase (cAMP) activity. Agonists such as DAMGO ([D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly3-ol]-enkephalin) and morphine decrease cAMP accumulation. Traditional antagonists, such as naloxone, naltrexone, β-chloronaltrexamine (β-CNA), 7-benzylidenenaltrexone (BNTX), and diprenorphine, further increase cAMP accumulation (cAMP overshoot) in morphine-treated cells. Naloxone, naltrexone, β-CNA, and diprenorphine were labeled inverse agonists because these antagonists produced effects opposite to those of agonists. Other antagonists such as 6β-naltrexol, CTOP (D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2), and CTAP (D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2) have been identified as possible neutral antagonists since these compounds failed to alter cAMP levels in this upregulated cAMP system. Furthermore, CTAP blocked the effects of both naloxone and morphine in these cells (Wang et al., 1994; 2001; Bilsky et al., 1996; Liu & Prather, 2001).

Conceivably, μ-opioid receptor antagonists in this scheme could be classified on a continuum of partial to full negative intrinsic efficacy under certain conditions in the same way μ-opioid receptor agonists are classified on a continuum of partial to full positive intrinsic efficacy. Data are very limited in functional assays that distinguish among antagonists in regards to negative intrinsic efficacy. In vivo, CTAP, CTOP, 6β-naltrexol, and β-CNA appear to be selective μ-opioid receptor antagonists in nondependent subjects (Gulya et al., 1988; Kramer et al., 1989; Adams et al., 1994; Porter et al., 2002; Sterious & Walker, 2003; Wang et al., 2004). However, the pharmacological profiles for CTAP, CTOP, and 6β-naltrexol are unique in morphine-dependent mice in that these antagonists failed to produce significant withdrawal jumping, one of the most characteristic signs of opiate withdrawal, whereas naloxone and naltrexone produce striking withdrawal jumping (Gulya et al., 1988; Wang et al., 1994; 2001; 2004). Interestingly, CTAP blocked the withdrawal jumping in mice produced by naloxone (Wang et al., 1994; Bilsky et al., 1996). Yet, in rats dependent on morphine, CTAP produced moderate withdrawal effects (Maldonado et al., 1992). In morphine-treated, electrically stimulated isolated guinea-pig ileum, CTAP produced effects similar to naloxone (Mundey et al., 2000). The discrepancies between these studies may be due to different dependence states of the preparations.

A common and reliable method for studying opioid dependence is the precipitated withdrawal jumping assay in mice. In this assay, mice are either implanted with a morphine pellet (Cowan, 1976; Miyamoto & Takemori, 1993) or injected with a single high dose of morphine (Smits, 1975; Wiley & Downs, 1979; Sofuoglu et al., 1990). After a specified time, an antagonist, usually naloxone, is administered and withdrawal jumping is observed within 15 min (Huidobro & Maggiolo, 1965; Way et al., 1969). The more dependent the mice, that is, the higher the morphine pretreatment dose, the lower the dose of naloxone required to elicit the withdrawal jumping (Way et al., 1969).

In the present study, five opioid antagonists were compared for their capacity to produce withdrawal jumping as well as paw tremors and weight loss, two additional signs of opioid withdrawal (Fernandez-Espejo et al., 1995; Broseta et al., 2002) in mice injected with a high pretreatment dose of 180 mg kg−1 morphine or a low pretreatment dose of 56 mg kg−1 morphine. Antagonists that produce withdrawal jumping after pretreatment with both high and low morphine doses are hypothesized to be strong inverse agonists possessing high negative intrinsic efficacy. On the other hand, antagonists that produce withdrawal jumping in mice treated with high but not low doses of morphine are hypothesized to be weaker inverse agonists possessing lower negative intrinsic efficacy. Finally, to further test the hypothesis that antagonists may differ along a continuum of negative intrinsic efficacy, alleged weaker inverse agonists were injected to block withdrawal jumping produced by stronger inverse agonists. It is hypothesized that a compound with less negative intrinsic efficacy would block the effects of a compound with greater negative intrinsic efficacy.

Methods

Subjects

Male, Swiss Webster mice (N=1308) weighing 15–30 g (Ace Animals, Inc., Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.) were group-housed in a colony room maintained under a 12-h light–dark cycle. Water and food were freely available in the home cages. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health.

Apparatus

Ten 4L Pyrex® graduated beakers (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, U.S.A.) were used during the precipitated withdrawal jumping. A CS-2000 scale (OHAUS, Forham Park, NJ, U.S.A.) was used to weigh the mice. A hand-held VWR counter (VWR International, West Chester, PA, U.S.A.) was utilized for counting jumps.

Procedure

The procedures used in these experiments were modified from Way et al. (1969) and Yano & Takemori (1977). Groups of 10–11 mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with either 56, 100, or 180 mg kg−1 morphine. After 3 h and 40 min, the mice were weighed and placed into 4000 ml Pyrex® graduated beakers for a 20 min habituation period. After the habituation period ended, the mice were injected with a single dose of antagonist, s.c. The number of jumps and paw tremors were recorded for 15 min. Jumping was defined as all four paws simultaneously off the floor. Paw tremors were defined as one or both paws shaking in a lateral fashion. At the end of the observation period, the mice were weighed again. During antagonist combination experiments, the mice were injected with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine. After 3 h and 40 min, the mice were injected with a dose of naltrexone, nalorphine, naloxonazine, or saline, s.c., and placed into the beakers. Jumping and the number of paw tremors were counted during the 20 min habituation period. After 20 min, naloxone was injected and the number of jumps and paw tremors were recorded.

Drugs

The following compounds were used: diprenorphine hydrochloride (HCl), morphine sulfate, nalorphine HCl, naloxone HCl, naltrexone HCl (generously supplied by National Institute on Drug Abuse, Rockville, MD, U.S.A.), and naloxonazine HCl (Sigma Biochemicals, Natick, MA, U.S.A.). All compounds were dissolved in saline and prepared to deliver each injection in a volume of 0.1–0.4 ml. Doses are expressed as the forms listed above. Saline was injected in a volume of 1 ml kg−1 of body weight.

Data analysis

The percentage of mice jumping or exhibiting paw tremors was calculated by dividing the number of mice exhibiting at least one withdrawal jump or one bout of paw tremors within the 15 min observation period by the total number of mice in the group. To determine the % of body weight loss, the weight loss at the conclusion of the experiment was divided by the average weight of the group prior to the morphine injection and multiplied by 100. Most experiments were performed in triplicate and data points from multiple experiments were averaged together to construct dose–response curves. Data for withdrawal jumping, paw tremors, and weight loss were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance using antagonist dose and pretreatment condition as factors (GraphPad Prism v. 4.0, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). If an antagonist failed to produce dose-dependent effects, the doses were averaged, resulting in a single value for a given behavioral effect (paw tremors and weight loss) and an unpaired t-test was performed. Significance was set at P<0.05. Dose–response curves for withdrawal jumping were analyzed by linear regression and ED50 values and 95% CL were determined (PharmToolsPro, v1.1.27, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.).

Results

Control experiments

Saline produced no jumping or paw tremors in mice after 4 h pretreatments of either 56 or 180 mg kg−1 morphine. These mice lost 1.2 and 0.7 g, or approximately 3 and 2% of their body weight, respectively (Table 2). Doses of 56 and 100 mg kg−1 naloxone produced no jumping or paw tremors in mice after 4 h pretreatments of saline. These mice lost 0.4 and 0.7 g, or approximately 1–2% of their body weight (data not shown). Pretreatment of 180 mg kg−1 morphine produced lethality in approximately 12% of the mice during the studies.

Table 2.

Average values across antagonist doses for the % mice exhibiting paw tremors and the % of body weight loss after 4 h pretreatment of either 56 or 180 mg kg−1 morphine

| Paw tremors (% mice±s.e.m.) | Weight loss (% body weight±s.e.m.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antagonist | 56 mg kg−1 Morphine | 180 mg kg−1 Morphine | 56 mg kg−1 Morphine | 180 mg kg−1 Morphine |

| Saline | 0 | 0 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| Naloxone | 51±4.5 | 36±9.1 | 6.4±1.8 | 5.2±0.37 |

| Naltrexone | 49±11 | 51±5.2 | 5.7±0.61 | 4.7±0.43 |

| Diprenorphine | 27±9.7 | 23±9.2 | 6.9±0.66 | 4.2±0.51a |

| Nalorphine | 11±7.1 | 12±5.8 | 6.8±0.31 | 5.5±0.75 |

| Naloxonazine | 48±16 | 21±10 | 6.3±0.76 | 3.1±0.50a |

Significantly different from 56 mg kg−1 morphine (P<0.05).

Naloxone experiments

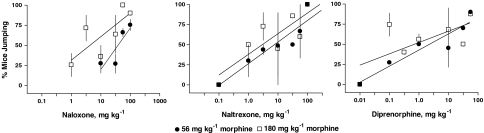

Naloxone (1.0–100 mg kg−1). produced dose-dependent (F3,3=14.09, P<0.03) withdrawal jumping after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine with ED50 values of 38 and 4.3 mg kg−1, respectively (Figure 1; Table 1). Naloxone was significantly more potent in eliciting withdrawal jumping after a pretreatment of 180 than 56 mg kg−1 morphine (F1,3=11.38, P<0.04). A dose of 100 mg kg−1 naloxone produced maximal withdrawal jumping in 91 and 90% of the mice after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively. Naloxone elicited paw tremors in 51 and 36% of the mice and produced 6.4 and 5.2% weight loss after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively (Table 2). However, the effects of naloxone on paw tremors and weight loss were not dose-dependent or different across treatment conditions.

Figure 1.

Effects of naloxone, naltrexone, and diprenorphine on withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated 4 h earlier with either 56 or 180 mg kg−1 morphine. Each point on the dose–response curve represents 1–3 experiments consisting of 7–11 mice each. Ordinate: % of mice exhibiting withdrawal jumping. Abscissa: dose of antagonist, in mg kg−1. Vertical bars represent the s.e.m. across experiments.

Table 1.

ED50 values for opioid antagonists to precipitate withdrawal jumping in mice after 4 h pretreatment of either 56, 100, or 180 mg kg−1 morphine

| Antagonist | Morphine pretreatment (mg kg−1) | ED50 values (mg kg−1) (95% CL) |

|---|---|---|

| Naloxone | 56 | 38 (13–100) |

| 100 | 25 (4.2–150) | |

| 180 | 4.3 (2.3–66) | |

| Naltrexone | 56 | 7.6 (2.5–25) |

| 180 | 2.1 (0.094–9.1) | |

| Diprenorphine | 56 | 2.3 (0.43–15) |

| 180 | 0.70 (0.033–520) | |

| Nalorphine | 56 | NAa |

| 180 | 26 (13–99) | |

| Naloxonazine | 56 | NAa |

| 180 | 50 (11–5100) |

Maximum % of mice jumping was less than 50%.

Naltrexone experiments

Naltrexone (0.1–100 mg kg−1). produced dose-dependent (F6,6=12.49, P<0.004) withdrawal jumping after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine with ED50 values of 7.6 and 2.1 mg kg−1, respectively (Figure 1; Table 1). These ED50 values were not significantly different between the two pretreatment conditions, however. A dose of 100 mg kg−1 naltrexone produced maximal withdrawal jumping in 100% of the mice after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 naloxone. Naltrexone was the only antagonist to dose-dependently elicit paw tremors (F1,6=4.55, P<0.04) in mice after 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine (Table 2). The average percentages of mice exhibiting paw tremors across naltrexone doses were 49 and 51% after a 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively. Naltrexone produced 5.7 and 4.7% weight loss after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively, although this effect was not dose-dependent or different across treatment conditions.

Diprenorphine experiments

Diprenorphine (0.01–56 mg kg−1). produced dose-dependent (F5,5=6.11, P<0.034) withdrawal jumping after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine with ED50 values of 2.3 and 0.7 mg kg−1, respectively (Figure 1; Table 1). These ED50 values were not significantly different between the two pretreatment conditions, however. A dose of 56 mg kg−1 diprenorphine produced maximal withdrawal jumping in approximately 90% of the mice after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine. Diprenorphine elicited paw tremors in 27 and 23% of the mice after pretreatment with 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively; these effects were not dose-dependent or different across treatment conditions (Table 2). Although the effects of diprenorphine on body weight loss were not dose-dependent, the percentage of body weight lost produced by diprenorphine after 180 mg kg−1 morphine (4.2%) was significantly less than after 56 mg kg−1 (6.9%) morphine (P<0.008).

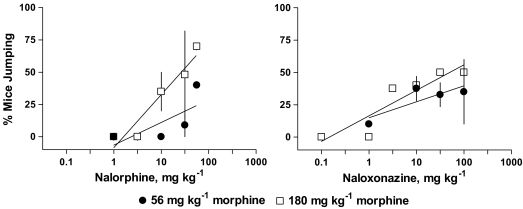

Nalorphine experiments

Nalorphine (1.0–56 mg kg−1) produced withdrawal jumping in approximately 40 and 70% of the mice after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively (Figure 2). There was not a significant effect of nalorphine dose or morphine pretreatment condition. The ED50 value for nalorphine to elicit withdrawal jumping after 4 h pretreatment of 180 mg kg−1 morphine was 26 mg kg−1; an ED50 could not be determined for nalorphine after 4 h pretreatment of 56 mg kg−1 morphine (Table 1). Nalorphine elicited paw tremors in 11 and 12% of the mice and produced 6.8 and 5.5% weight loss after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively (Table 2). However, the effects of nalorphine on paw tremors and weight loss were not dose-dependent or different across treatment conditions.

Figure 2.

Effects of nalorphine and naloxonazine on withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated 4 h earlier with either 56 or 180 mg kg−1 morphine. Each point on the dose–response curve represents 1–4 experiments consisting of 7–11 mice each. See Figure 1 for other details.

Naloxonazine experiments

Naloxonazine (0.1–100 mg kg−1) produced withdrawal jumping in approximately 37 and 50% of the mice after 4 h pretreatment of 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively (Figure 2). There was not a significant effect of naloxonazine dose or morphine pretreatment condition. The ED50 value for naloxonazine to elicit withdrawal jumping after 4 h pretreatment of 180 mg kg−1 morphine was 50 mg kg−1; an ED50 could not be determined for naloxonazine after 4 h pretreatment of 56 mg kg−1 morphine (Table 1). Naloxonazine elicited paw tremors in 48 and 21% of the mice after pretreatment with 56 and 180 mg kg−1 morphine, respectively; these effects were not dose-dependent or different across treatment conditions (Table 2). Although the effects of naloxonazine on body weight loss were not dose-dependent, the percentage of body weight lost produced by naloxonazine after 180 mg kg−1 morphine (6.3%) was significantly greater than after 56 mg kg−1 (3.1%) morphine (P<0.04).

Combination experiments

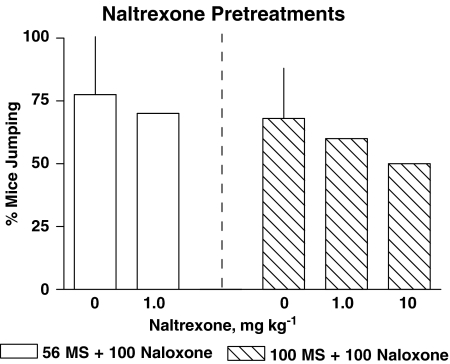

In mice treated with 56 mg kg−1 morphine 4 h prior to testing, saline pretreatment failed to significantly alter the naloxone dose–response curve (ED50 79 mg kg−1 (51–122), data not shown) relative to naloxone alone (Table 2). In some of the combination experiments, 100 mg kg−1 was chosen over 180 mg kg−1 morphine because nalorphine, naloxonazine, and naltrexone precipitated a reasonable amount of withdrawal jumping after the mice were pretreated with 180 mg kg−1 morphine (Figures 1 and 2). The morphine dose was titrated to 100 mg kg−1 to ensure nalorphine and naloxonazine produced jumping in 50% or less of the mice. A dose of 1.0 mg kg−1 naltrexone alone precipitated withdrawal jumping in 25% (N=10) of the mice pretreated with 56 mg kg−1 morphine (Figure 1). Doses of 1.0 and 10 mg kg−1 naltrexone alone precipitated withdrawal jumping in 50% (N=10) and 40% (N=10) of the mice pretreated with 100 mg kg−1 morphine (data not shown). Twenty min pretreatments of 1.0 or 10 mg kg−1 naltrexone failed to significantly alter naloxone precipitated withdrawal in mice injected with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine 4 h prior to testing (Figure 3). Naltrexone pretreatments did not alter paw tremors or the % body weight loss produced by naloxone in mice pretreated with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine.

Figure 3.

Effects of 1.0 or 10 mg kg−1 naltrexone pretreatments on naloxone–precipitated withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated 4 h earlier with either 56 (open bars) or 100 mg kg−1 (striped bars) morphine. Naltrexone was administered 20 min prior to naloxone. Bars above 0 represent control naloxone-precipitated jumping from Figure 1. Variance is expressed as s.t.d. Combination naltrexone and naloxone bars represent a single experiment in 10 mice. Ordinate: % of mice exhibiting withdrawal jumping. Abscissa: dose of naltrexone pretreatment, in mg kg−1.

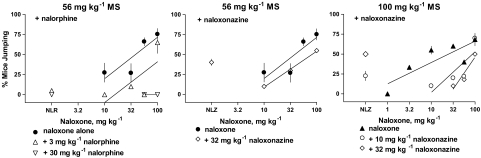

Pretreatments of nalorphine (3 and 30 mg kg−1) and naloxonazine (10 and 32 mg kg−1) for 20 min blocked naloxone precipitated withdrawal in mice injected with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine 4 h prior to testing (Figure 4). A dose of 3 mg kg−1 nalorphine produced a four-fold shift to the right in the naloxone dose–response curve after mice received a 4 h pretreatment of 56 mg kg−1 morphine. A higher dose of nalorphine completely eliminated the capacity of 56 and 100 mg kg−1 naloxone to produce withdrawal jumping. A dose of 10 mg kg−1 naloxonazine failed to alter the naloxone dose–response curve after a 4 h pretreatment of 56 mg kg−1 morphine (data not shown). However, a higher dose of 32 mg kg−1 naloxonazine shifted the naloxone dose–response curve two-fold to the right after a 4 h pretreatment of 56 mg kg−1 morphine. To further characterize the capacity of naloxonazine to block naloxone, 10 or 32 mg kg−1 naloxonazine was administered 15 min prior to naloxone in mice after a 4 h pretreatment of 100 mg kg−1 morphine. The ED50 for naloxone to precipitate withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated with 100 mg kg−1 morphine was 25 mg kg−1 (Table 2). Doses of 10 and 32 mg kg−1 naloxonazine shifted the naloxone dose–response curve 6- and 15-fold to the right (P<0.05). Nalorphine did not alter paw tremors or weight loss produced by naloxone. Naloxonazine significantly increased the percentage of mice exhibiting paw tremors after naloxone from 51% (Table 2) to 94% (P<0.008) in mice pretreated with 56 mg kg−1 morphine. Although 10 and 32 mg kg−1 naloxonazine increased the percentage of mice exhibiting paw tremors after naloxone from 38% to 80% and 73%, respectively, in mice pretreated with 100 mg kg−1 morphine, these differences were not significant. Naloxonazine pretreatments did not alter the % body weight loss produced by naloxone in mice pretreated with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine.

Figure 4.

Effects of nalorphine and naloxonazine pretreatments on naloxone-precipitated withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated 4 h earlier with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine. Nalorphine and naloxonazine were administered 20 min prior to naloxone. Control naloxone data from Figure 1. Each point in the combination experiment represents 1–3 experiments consisting of 7–11 mice. Points above NLR and NLZ represent the effects of nalorphine (N=30) and naloxonazine (N=30–44) alone in the combination experiments. See Figure 1 for other details.

Discussion

In the present study, naloxone and naltrexone elicited robust withdrawal jumping, paw tremors, and weight loss in mice that were injected with 56 or 180 mg kg−1 morphine 4 h prior to testing. These findings are in agreement with approximately 30 years of research using similar acute dependence procedures in mice. For example, other investigators have precipitated withdrawal jumping in mice treated with acute doses of 4–100 mg kg−1 of morphine and tested doses of 1–128 mg kg−1 naloxone (Kosersky et al., 1974; Smits, 1975; Sofuoglu et al., 1990). Similar pretreatment times of 3–5 h were used (Wiley & Downs, 1979) in these studies although shorter pretreatment times were required after much lower pretreatment doses of morphine (Smits, 1975; Linseman, 1977). Lower doses of naloxone and naltrexone produce withdrawal jumping in mice when higher pretreatment doses of morphine are injected (e.g., Way et al., 1969). In the present study, naloxone and naltrexone were eight- and three-fold more potent, respectively, when 180 mg kg−1 morphine was injected as compared to 56 mg kg−1 morphine. The observation that the precipitated withdrawal jumping is dependent on the dose of agonist and antagonist used as well the time between these injections indicates that this is a robust behavioral response sensitive to pharmacological manipulations.

Using this versatile assay, five opioid antagonists were compared for their potency and effectiveness to produce withdrawal jumping. The rank order of potency for the five antagonists to produce withdrawal jumping after pretreatment with 180 mg kg−1 morphine was diprenorphine>naltrexone>naloxone⩾nalorphine=naloxonazine. This rank order of potency is in general agreement with the binding affinity of these antagonists at the μ-opioid receptor (Toll, 1992; Lee et al., 1999). One exception was naloxonazine, which exhibits higher binding affinity than nalorphine (Johnson & Pasternak, 1984); yet, in the present study, the two compounds were approximately equipotent. The five antagonists were also distinguishable based on their capacity or effectiveness to elicit withdrawal jumping. In the present study, naloxone and naltrexone produced withdrawal jumping in most mice after treatment with either 56 or 180 mg kg−1 morphine. Diprenorphine also produced withdrawal jumping in a majority of mice; however, the slopes of the dose–response curves were shallow. Nalorphine and naloxonazine produced withdrawal jumping in approximately half the mice after a pretreatment dose of 180 mg kg−1 morphine. When a lower treatment dose of 56 mg kg−1 morphine was injected, nalorphine and naloxonazine were essentially ineffective. Therefore, based on the capacity to produce withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated with morphine, the rank order of effectiveness was naloxone=naltrexone⩾diprenorphine>nalorphine⩾naloxonazine.

In cell culture, it has become clear that opioid antagonists can differ along a continuum of inverse agonism at δ receptors (e.g., Costa & Herz, 1989) and more recently at μ-opioid receptors (e.g., Wang et al., 2004). Naloxone, naltrexone, β-CNA, BNTX, and diprenorphine are proposed inverse agonists because these compounds produce effects opposite to those of agonists in vitro, especially in morphine-treated cells (Wang et al., 2001; 2004; Brillet et al., 2003). Other antagonists such as 6β-naltrexol, CTOP, CTAP, and nalorphine are proposed neutral antagonists in vitro (Wang et al., 1994; 2001). In vivo, 6β-naltrexol, CTOP, CTAP, and nalorphine failed to produce significant withdrawal jumping, whereas naloxone and naltrexone produce striking withdrawal jumping in morphine-dependent mice (Gulya et al., 1988; Wang et al., 1994; 2001; 2004; present study). However, in rats dependent on morphine, CTAP produced moderate withdrawal effects (Maldonado et al., 1992) and enhanced adenylyl cyclase activity in vitro similar to inverse agonists (Szücs et al., 2004). Similarly, nalorphine can precipitate some withdrawal jumping under higher dependence conditions such as morphine pellet implantation (Cowan, 1976). Interestingly, naltrexone, CTAP, nalorphine, nalbuphine, and morphine withdrawal shared discriminative-stimulus effects in pigeons maintained on daily morphine injections (Walker et al., 2004). Yet, under other in vitro and in vivo conditions, nalorphine and nalbuphine, but not naltrexone, produce μ-opioid agonist effects (Young et al., 1992; Walker et al., 2001; Gharagozlou et al., 2003). However, the observation that nalorphine is a partial agonist under some assay conditions probably does not account for the antagonism of naloxone-precipitated withdrawal jumping under the present assay conditions since early studies demonstrated that low doses of agonists given shortly before naloxone actually increases withdrawal jumping (Bläsig et al., 1976) and decreases the naloxone ED50 to produce jumping (Cheney et al., 1972). Therefore, classification of antagonists as partial agonists, inverse agonists, or neutral antagonists depends on the conditions of a given assay, as would be predicted from receptor theory (Kenakin, 2004).

The observation in the present study that all five antagonists produced at least some degree of withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated with 180 mg kg−1 but not 56 mg kg−1 morphine is analogous to relative efficacy differences detected between high- and low-efficacy agonists in certain assays. For example, when a noxious stimulus is low, both high- and low-efficacy agonists produce antinociception. However, when the noxious stimulus is increased, only the higher efficacy agonists possess enough intrinsic efficacy to produce an antinociceptive effect (Shaw et al., 1988; Walker et al., 1993; Cook et al., 2000). Correspondingly, inverse agonists possessing stronger negative intrinsic efficacy, such as naloxone and naltrexone, precipitate withdrawal jumping after both high and low morphine pretreatment doses. Inverse agonists possessing weaker negative intrinsic efficacy, such as nalorphine and naloxonazine, only precipitate withdrawal jumping when the mice were highly dependent, that is, after high pretreatment doses of morphine. Intrinsic efficacy is a fluid property depending on the experimental parameters and the state of the receptor (Fathy et al., 1999; Yang & Lanier, 1999) although the rank order of negative intrinsic efficacy should remain the same for a group of inverse agonists across assays if intrinsic efficacy is the relevant parameter that distinguishes among the compounds. For example, nalorphine will precipitate more withdrawal jumping under higher dependence conditions such as chronic treatment (Cowan, 1976; France & Morse, 1989) than observed in the present study. Nevertheless, naloxone and naltrexone still produce more pronounced withdrawal effects than nalorphine under any dependence condition.

Theoretically, just as low efficacy agonists block the antinociceptive effects of high-efficacy agonists when the stimulus intensity is high (Walker et al., 1993; Cook et al., 2000), neutral antagonists or weak inverse agonists should block the actions of strong inverse agonists when the stimulus intensity is low. Indeed, proposed weak inverse agonists nalorphine and naloxonazine blocked naloxone-induced withdrawal jumping in mice treated with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine. Similarly, CTAP and nalorphine blocked the effects of naloxone and morphine in vitro (Wang et al., 1994; 2001; Liu & Prather, 2001) as well as in vivo (Wang et al., 1994; Bilsky et al., 1996; present study). However, pretreatments of strong inverse agonist naltrexone failed to alter naloxone precipitated withdrawal jumping in mice pretreated with either 56 or 100 mg kg−1 morphine. Therefore, antagonism of naloxone-precipitated jumping was only observed by proposed neutral antagonists or weak inverse agonists such as CTAP, nalorphine, and naloxonazine (Bilsky et al., 1996; present study). Taken together, these data suggest that nalorphine, naloxonazine, CTAP and 6β-naltrexol would possess less negative intrinsic efficacy than naloxone and naltrexone. Theoretically, to block the effects of a strong inverse agonist, a compound would need to possess less negative intrinsic efficacy than the strong inverse agonist. Practically, however, a weaker inverse agonist would only be observed to block a stronger inverse agonist in an assay in which the weak inverse agonist does not elicit a strong effect.

Although these antagonists possess slightly different selectivities for multiple opioid receptors (Gillan & Kosterlitz, 1982; Geary & Wooten, 1985; Goldstein & Naidu, 1989; Mansour & Watson, 1993), affinity alone does not appear responsible for the observed results. For example, the antagonist with the highest affinity for the μ-opioid receptor, diprenorphine (Lee et al., 1999), was not the most effective antagonist to elicit jumping. Naloxonazine binds reversibly to both subtypes of μ-opioid receptors shortly after administration, but binds irreversibly to μ1-opioid receptor subtype after 24 h (Hahn et al., 1982; Ling et al., 1985a). Clearly, naloxonazine's antagonism of naloxone-precipitated jumping indicates that the two compounds are competing at similar opioid receptors whether reversibly or irreversibly. In vivo, naloxonazine has complex effects that may depend on the species tested. For example, the antinociceptive, gastrointestinal propulsion, and respiratory effects of naloxonazine appear to be mediated by subtypes of μ-opioid receptors in rodents (Ling et al., 1985a, 1985b; Heyman et al., 1988), but not necessarily rhesus monkeys (Gatch et al., 1996). Despite these subtle differences in binding profiles, a reasonable hypothesis remains that the differential capacity of naloxonazine to elicit withdrawal jumping relative to naloxone may be related to the disparity between negative intrinsic efficacies for the two compounds.

Another finding in the present study indicates that some measures of opioid withdrawal in the acute dependence model may be more sensitive indicators of inverse agonism or negative intrinsic efficacy than others. For example, all antagonists produced some degree of dose-dependent withdrawal jumping generally related to the acute pretreatment dose of morphine. Although all antagonists consistently produced some degree of body weight loss and paw tremors in mice acutely treated with morphine, these effects were not dose-dependent and not necessarily related to the morphine treatment dose. In earlier studies of morphine dependence, withdrawal symptoms such as jumping were most readily observed after injection with strong opioid antagonists and labeled ‘dominant' withdrawal symptoms. Other opioid compounds, such as nalorphine, were less effective than naloxone in producing jumping (Bläsig et al., 1973; 1976). On the other hand, other withdrawal signs, such as wet dog shakes and writhing, were more likely to appear under more moderate morphine dependence conditions, later in the observation period (Bläsig et al., 1973), or when withdrawal jumping was blocked by other compounds such as benzodiazepines (Maldonado et al., 1991; Valverde et al., 1992). These other symptoms were labeled ‘recessive' withdrawal symptoms and appeared to have a somewhat reciprocal relationship with the occurrence of withdrawal jumping (Bläsig et al., 1973). In the present acute dependence study, the mice were mildly to moderately dependent given the observed levels of withdrawal jumping, paw tremors, and weight loss. Interestingly, the highest frequency of paw tremors (a possible ‘recessive' withdrawal symptom) was observed when naloxonazine blocked naloxone-precipitated withdrawal jumping. Overall, in our studies, withdrawal jumping was the most robust and sensitive behavioral index of inverse agonism or negative intrinsic efficacy. Future behavioral studies with combinations of other weak and strong inverse agonists will allow us to further delineate the possible reciprocal relationship of paw tremors and withdrawal jumping.

Taken together, these findings suggest that antagonists may vary according to negative intrinsic efficacy, as indicated by their differential capacity to produce withdrawal jumping and the capacity of some weaker (nalorphine and naloxonazine) but not strong inverse agonists (naltrexone) to block the effects produced by naloxone in mice acutely treated with morphine. Conceivably, μ-opioid receptor antagonists may be classified on a continuum of partial to full negative intrinsic efficacy under certain conditions in the same way that μ-opioid receptor agonists are classified on a continuum of partial to full positive intrinsic efficacy. The observations in the present series of experiments contribute to recent efforts by other investigators (Bilsky et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2004) to provide an in vivo systematic classification of antagonists in relation to negative intrinsic efficacy. Additional and complementary in vitro and in vivo experiments that vary assay conditions are required to make definitive conclusions regarding the relationship of inverse agonism, negative intrinsic efficacy, and opioid dependence.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edward K. Brown Jr, Amy M. Falcone, Richard W. Hass, Stephen J. Kohut, and Amy Schneider for their technical assistance. This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA10776 and the Einstein Society Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BNTX

7-benzylidenenaltrexone

- β-CNA

β-chloronaltrexamine

- CTAP

D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2

- CTOP

D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2

- s.e.m.

standard error of the mean

References

- ADAMS J.U., GELLER E.B., ADLER M.W. Receptor selectivity of icv morphine in the rat cold water tail-flick test. Drug Al. Depend. 1994;35:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BILSKY E.J., BERNSTEIN R.N., WANG Z., SADEE W., PORRECA F. Effects of naloxone and D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2 and the protein kinase inhibitors H7 and H8 on acute morphine dependence and antinociceptive tolerance in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;277:484–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLÄSIG J., HERZ A., REINHOLD K., ZIEGLGANSBERGER S. Development of physical dependence on morphine in respect to time and dosage and quantification of the precipitated withdrawal syndrome in rats. Psychopharmacologia. 1973;33:19–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00428791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLÄSIG J., HÖLLT V., HERZ A., PASCHELKE G. Comparison of withdrawal precipitating properties of various morphine antagonists and partial agonists in relation to their stereospecific binding to brain homogenates. Psychopharmacologia. 1976;46:41–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00421548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRILLET K., KIEFFER B.L., MOSSATTE D. Enhanced spontaneous activity of the mu opioid receptor by cysteine mutations: characterization of a tool for inverse agonist screening. BMC Pharmacol. 2003;3:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROSETA I., RODRIGUEZ-ARIAS M., STINUS L., MINARRO J. Ethological analysis of morphine withdrawal with different dependence programs in male mice. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;2:335–347. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURFORD N.T., WANG D.X., SADEE W. G-protein coupling of mu-opioid receptors (OP3) elevated basal-signaling activity. Biochem. J. 2000;348:531–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENEY D.L., JUDSON B.A., GOLDSTEIN A. Failure of an opiate to protect mice against naloxone precipitated withdrawal. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1972;182:189–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTA T., HERZ A. Antagonists with negative intrinsic activity at delta opioid receptors coupled to GTP-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989;86:7321–7325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOK C.D., BARRET A.C., ROACH E.L., BOWMAN J.R., PICKER M.J. Sex-related differences in the antinociceptive effects of opioids: importance of rat genotype, nociceptive stimulus intensity, and efficacy at the mu opioid receptor. Psychopharmacology. 2000;150:430–442. doi: 10.1007/s002130000453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COWAN A. Use of the mouse-jumping test for estimating antagonistic potencies of morphine antagonists. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1976;28:177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1976.tb04126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FATHY D.B., LEEB T., MATHIS S.A., LEEB-LUNDBERG L.M.F. Spontaneous human B2 bradykinin receptor activity determines the action of partial agonists as agonists or inverse agonists – effect of basal desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:29603–29606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDEZ-ESPEJO E., CADOR M., STINUS L. Ethopharmacological analysis of naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal syndrome in rats: a newly-developed ‘etho-score'. Psychopharmacology. 1995;122:122–130. doi: 10.1007/BF02246086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANCE C.P., MORSE W.H. Pharmacological characterization of supersensitivity to naltrexone in squirrel monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;250:928–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GATCH M.B., LIGUORI A., NEGUS S.S., MELLO N.K., BERGMAN J., LIGUORI T. Naloxonazine antagonism of levorphanol-induced antinociception and respiratory depression in rhesus monkeys. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;298:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00769-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEARY W.A., WOOTEN G.F. Regional saturation studies of 3H-naloxone binding in the naïve, dependent and withdrawal states. Brain Res. 1985;360:214–223. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHARAGOZLOU P., DEMIRCI H., CLARK J.D., LAMEH J. Activity of opioid ligands in cells expressing cloned μ-opioid receptors. BMC Pharmacol. 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- GILLAN M.G.C., KOSTERLITZ H.W. Spectrum of the μ-, δ- and κ-binding sites in homogenates of rat brain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1982;77:461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1982.tb09319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDSTEIN A., NAIDU A. Multiple opioid receptors: ligand selectivity profiles and binding site signatures. Mol. Pharmacol. 1989;36:265–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GULYA K., KRIVAN M., NYOLCZAS N., SARNYAI Z., KOVACS G.L. Central effects of the potent and highly selective μ opioid antagonist D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2 (CTOP) in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;150:355–360. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAHN E.F., CARROLL-BUATTI M., PASTERNAK G.W. Irreversible opiate agonists and antagonists: the 14-hydroxydihydromorphinone azines. J. Neurosci. 1982;2:572–576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-05-00572.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEYMAN J.S., WILLIAMS C.L., BURKS T.F., MOSBERG H.I., PORRECA F. Dissociation of opioid antinociception and central gastrointestinal propulsion in the mouse: studies with naloxonazine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;245:238–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUIDOBRO F., MAGGIOLO C. Studies on morphine. IX. On the intensity of the abstinence syndrome to morphine induced by daily injections of nalorphine in white mice. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1965;158:97–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON N., PASTERNAK G.W. Binding of [3H]naloxonazine to rat brain membranes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1984;26:477–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENAKIN T. Efficacy as a vector: the relative prevalence and paucity of inverse agonism. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:2–11. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOSERSKY D.S., HARRIS R.A., HARRIS L.S. Naloxone-precipitated jumping activity in mice following the acute administration of morphine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1974;26:122–124. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(74)90084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAMER T.H., SHOOK J.E., KAZMIERSKI W., AYRES E.A., WIRE W.S., HRUBY V.J., BURKS T.F. Novel peptidic mu opioid antagonists: pharmacologic characterization in vitro and in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;249:544–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE K.O., AKIL H., WOODS J.H., TRAYNOR J.R. Differential binding properties of oripavines at cloned μ- and δ-opioid receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;378:323–330. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LING G.S.F., SIMANTOV R., CLARK J.A., PASTERNAK G.W. Naloxonazine actions in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985a;129:133–137. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LING G.S.F., SPIEGEL K., LOCKHART S.H., PASTERNAK G.W. Separation of opioid analgesia from respiratory depression: evidence for different receptor mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1985b;232:149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINSEMAN M.A. Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal as a function of the morphine–naloxone interval. Psychopharmacology. 1977;54:159–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00426773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU J.G., PRATHER P.L. Chronic exposure to m-opioid agonists produces constitutive activation of m-opioid receptors in direct proportion to the efficacy of agonist used for pretreatment. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;60:53–62. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALDONADO R., MICO J.A., VALVERDE O., SAAVEDRA M.C., LEONSEGUI I., GIBERT-RAHOLA J. Influence of different benzodiazepines on the experimental morphine abstinence syndrome. Psychopharmacology. 1991;105:197–203. doi: 10.1007/BF02244309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALDONADO R., NEGUS S.S., KOOB G. Precipitation of morphine withdrawal syndrome in rats by administration of mu-, delta-, and kappa-selective opioid antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31:1231–1241. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90051-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANSOUR A., WATSON S.J.Anatomical distribution of opioid receptors in mammalians: and overview Opioids 1993Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 79–105.ed. Herz A., pp [Google Scholar]

- MIYAMOTO Y., TAKEMORI A.E. Inhibition of naloxone-precipitated withdrawal jumping by I.c.v. and i.t. administration of saline in morphine-dependent mice. Life Sci. 1993;52:1129–1134. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUNDEY M.K., ALI A., MASON R., WILSON V.G. Pharmacological examination of contractile response of the guinea-pig isolated ileum produced by m-opioid receptor antagonists in the presence of, and following exposure to, morphine. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:893–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTER S.J., SOMOGYI A.A., WHITE J.M. In vivo and in vitro potency studies of 6-beta-naltrexol, the major human metabolite of naltrexone. Addict. Biol. 2002;7:219–225. doi: 10.1080/135562102200120442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHAW J.S., ROURKE J.D., BURNS K.M. Differential sensitivity of antinociceptive tests to opioid agonists and partial agonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;95:578–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb11679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITS S.E. Quantification of physical dependence in mice by naloxone-precipitated jumping after a single dose of morphine. Res. Commun. Chem. Path. Pharmacol. 1975;10:651–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOFUOGLU M., SATO J., TAKEMORI A.E. Maintenance of morphine dependence by naloxone in acutely dependent mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;254:841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STERIOUS S.N., WALKER E.A. Potency differences for D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2 as an antagonist of peptide and alkaloid μ-agonists in an antinociception assay. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;304:301–309. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.042093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SZÜCS M., BODA K., GINTZLER A.R. Dual effects of DAMGO [D-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-enkephalin and CTAP(D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2) on adenylyl cyclase activity: implications for μ-opioid receptor Gs coupling. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;310:256–262. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOLL L. Comparison of mu opioid receptor binding on intact neuroblastoma cells with guinea pig brain and neuroblastoma cell membranes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;260:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALVERDE O., MICO J.A., MALDONADO R., GIBERT-RAHOLA J. Changes in benzodiazepine-receptor activity modify morphine withdrawal syndrome in mice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1992;80:293–300. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(92)90064-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER E.A., BUTELMAN E.R., DECOSTA B.R., WOODS J.H. Opioid thermal antinociception in rhesus monkeys: receptor mechanisms and temperature dependency. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993;267:280–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER E.A., PICKER M.J., DYKSTRA L.A. Three-choice discrimination in pigeons is based on relative efficacy differences among opioids. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:389–396. doi: 10.1007/s002130100714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER E.A., PICKER M.J., GRANGER A., DYKSTRA L.A. Effects of opioids in morphine-treated pigeons trained to discriminate among morphine, the low-efficacy agonist nalbuphine and saline. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;310:150–158. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.058503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG D., RAEHAL K.M., BILSKY E.J., SADEE W. Inverse agonists and neutral antagonists at μ opioid receptor (MOR): possible role of basal receptor signaling in narcotic dependence. J. Neurochem. 2001;77:1590–1600. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG D., RAEHAL K.M., LIN E.T., LOWERY J.J., KIEFFER B.L., BILSKY E.J., SADEE W. Basal signaling activity of μ-opioid receptor in mouse brain: role in narcotic dependence. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004;308:512–520. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG D., SURRAT C.R., SADEE W. Calmodulin regulation of basal and agonist-stimulated G protein coupling by the m-opioid receptor (OP3) in morphine-pretreated cells. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:763–771. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Z., BILSKY E.J., PORRECA F., SADEE W. Constitutive mu opioid receptor activation as a regulatory mechanism underlying narcotic tolerance and dependence. Life Sci. 1994;54:PL339–PL350. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Z., BILSKPL E.J., WANG D., PORRECA F., SADEE W. 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine inhibits basal μ-opioid receptor phosphorylation and reverses acute morphine tolerance and dependence in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;371:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAY E.L., LOH H.H., SHEN F.H. Simultaneous quantitative assessment of morphine tolerance and physical dependence. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1969;167:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILEY J.N., DOWNS D.A. Naloxone-precipitated jumping in mice pretreated with acute injections of opioids. Life Sci. 1979;25:797–802. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(79)90525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG Q., LANIER S.M. Influence of G protein type on agonist efficacy. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:651–656. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANO I., TAKEMORI A.E. Inhibition by naloxone of tolerance and dependence in mice treated acutely and chronically with morphine. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1977;16:721–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOUNG A.M., MASAKI M.A., GEULA C. Discriminative stimulus effects of morphine: effects of training dose on agonist and antagonist effects of mu opioids. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;261:246–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]