Abstract

The cytokines tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interleukin-1β (IL-1B) induce endothelial cells to recruit leukocytes. However, the exact adhesion and activation mechanisms induced by each cytokine, and their relative sensitivities to modulation by endothelial exposure to shear stress remain unclear.

We cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) in glass capillaries at various shear stresses, with TNFα or IL-1B added for the last 4 h. Subsequently, human neutrophils were perfused over the HUVEC, and adhesion and migration were recorded.

Both cytokines induced dose-dependent capture of neutrophils. However, while conditioning of HUVEC by increasing shear stress for 24 h diminished their response to TNFα, the response of HUVEC to IL-1B was similar at all shear stresses. The differing sensitivities were evident at levels of adhesive function and mRNA for adhesion molecules and chemokines.

Analysis of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)/Rel family of transcription factors showed that their expression and activation were modified by exposure to shear stress, but did not obviously explain differential responses to TNFα and IL-1B.

Antibodies against selectins were effective against capture of neutrophils on TNFα-treated but not IL-1B-treated HUVEC. Stable adhesion was supported by β2-integrins in each case. Activation of neutrophils occurred dominantly through CXC-chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) for TNFα-treated HUVEC, while blockade of CXCR1, CXCR2 and of platelet-activating factor receptors caused additive inhibition of migration on IL-1B-treated HUVEC.

The mechanisms which underlie neutrophil recruitment, and their modulation by the haemodynamic environment, differ between cytokines. Interventions aimed against leukocyte recruitment may not operate equally in different inflammatory milieu.

Keywords: Endothelium, cytokines, shear stress, leukocyte adhesion, migration

Introduction

The cytokines tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interleukin-1β (IL-1B) are key regulators of inflammation (Dinarello, 2002; Pober, 2002). Endothelial cells treated with either cytokine are able to induce each stage in the capture and transendothelial migration of flowing leukocytes in vitro and in vivo (Smith et al., 1991; Luscinskas et al., 1995; Bahra et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 2001; Young et al., 2002). While the responses to the two cytokines appear broadly similar, there are differences in the molecular mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment that they induce. Intravital studies and in vitro flow-based studies of adhesion to endothelium agree that capture of flowing leukocytes, especially neutrophils, is mediated by endothelial P- and E-selectin when TNFα is the agonist (Kunkel et al., 1997; Bahra et al., 1998). In the case of IL-1B stimulation, capture from flow is supported by E-selectin and leukocyte L-selectin, although blockade of these receptors only partially reduces adhesion in either type of model (Smith et al., 1991; von Andrian et al., 1992; Abbassi et al., 1993; Olofsson et al., 1994). Stable adhesion and migration in all models appears to depend on binding of activated neutrophil β2-integrins (Smith et al., 1991; von Andrian et al., 1992; Bahra et al., 1998). However, again, the agents activating the neutrophils may differ. Thus, in a recent study it was shown that platelet-activating factor (PAF) and leukotriene B4 induced stable adhesion and migration in murine vessels stimulated with IL-1B, but neither agent was implicated in these responses when TNFα was the agonist (Young et al., 2002). We found that chemokine(s) acting through CXC-chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2) were responsible for activation and migration when neutrophils were perfused over TNFα-stimulated endothelial monolayers (Luu et al., 2000), but there has been no definition of the chemotactic agents active in flow models of IL-1B-treated endothelial cells.

An additional complication arises because it has become increasingly clear that responses of endothelial cells are influenced by their haemodynamic environment (Lelkes, 1999; Topper JN & Gimbrone Jr MA, 1999). In particular, expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines can be modified by changes in the fluid shear stress to which endothelial cells are exposed (e.g., Nagel et al., 1994; Shyy et al., 1994; Sampath et al., 1995). Of particular relevance here are recent studies which indicate that conditioning by different levels of shear stress modifies the response to TNFα (Surapisitchat et al., 2001; Sheikh et al., 2003; Yamawaki et al., 2003). For instance, we found that pre-exposure of HUVEC for 24 h to increasing shear stress caused progressive reduction in their response to TNFα as judged by adhesion and migration of flowing neutrophils (Sheikh et al., 2003). This could be attributed to inhibition of TNFα-induced upregulation of E-selectin and of CXC-chemokines. We are not aware of reports showing whether such modulation by shear applies to responses to IL-1B. However, it is likely that inflammatory responses in different organs or different parts of the vascular tree vary depending on the conditioning of the endothelial cells by the local physical environment, and possible that this conditioning has unequal effects on responses to different stimuli.

The foregoing illustrates our incomplete understanding of the mechanisms supporting leukocyte recruitment in response to different inflammatory stimuli, under different circulatory conditions. This may be important for the rational design of pharmacological interventions against inflammation, because of the implication that the efficacy of a specific agent may depend on the local inflammatory milieu. We previously reported details of the mechanisms underlying the different stages of adhesion and migration of flowing neutrophils on endothelial cells treated with TNFα (Bahra et al., 1998; Luu et al., 2000; Luu et al., 2003), and also of the modifications that occurred when the endothelial cells were cultured at different levels of shear stress (Sheikh et al., 2003). Here we describe responses to IL-1B for endothelial cells cultured with or without flow, along with direct comparions to TNFα-treated cells under selected conditions. The results show that sensitivity to shear modulation is not the same for responses to TNFα and IL-1B, and give further details of the different mechanisms of adhesion and migration of neutrophils induced by the two cytokines.

Methods

Culture of endothelial cells under static or flow conditions

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated as previously described (Cooke et al., 1993) and maintained in medium 199 (M199; Invitrogen, Paisley, U.K.) containing 28 μg ml−1 gentamycin, 2.5 μg ml−1 amphotericin B (both, Sigma, Poole, U.K.) plus either 20% fetal calf serum and 1 ng ml−1 epidermal growth factor (Sigma) (Sheikh et al., 2003) or 20% human serum (AB blood type; National Blood Transfusion Service, Birmingham, U.K.) and 50 U ml−1 sodium-heparin (CP Pharmaceuticals, Wrexham, U.K.) (Bahra et al., 1998), until confluent. Primary cultures were dissociated with trypsin EDTA (Sigma) and passaged into rectangular glass capillaries (microslides; internal width 3 mm, depth 0.3 mm), which had been coated with collagen/gelatin as described (Cooke et al., 1993; Rainger et al., 1995). Seeding was at a density that yielded confluent monolayers within 24 h. Each experiment used first passage HUVEC from a different donor.

The flow-based culture system has been described in detail recently (Sheikh et al., 2004). After seeding with HUVEC for 1 h, microslides were placed into specially constructed glass dishes, and attached to glass tubing which had been fused into the wall. Silicon rubber tubing (Tygon R1000; Fisher, Loughborough, U.K.) was connected to each external arm. The dish contained culture medium and was placed in a humidified CO2 incubator (Nuaire DH; Triple Red, Thame, Oxfordshire, U.K.). The tubing was passed through a port in the incubator wall. The tubing from two adjacent arms (one attached to a microslide and one empty) was connected and placed into a multichannel, eight-roller pump (model 502S; Watson Marlow Ltd) forming a continuous flow loop. The bore of the pump tubing was chosen to give the desired flow rate and hence wall shear stress (0.3, 1.0 or 2.0 Pa) in the microslide for each experiment, for a single pump speed. The pump and external tubing were enclosed in a perspex box, thermostatically regulated at 37°C. The tubing from a separate microslide in each dish was connected to a separate pump. This pumped a small amount of medium through the microslide once an hour, to enable prolonged growth under our standard, static conditions (Cooke et al., 1993; Rainger et al., 1995). Three separate dishes could be cultured in parallel at any time.

There were two main culture protocols: (i) HUVEC were cultured under static conditions for 24 h and then TNFα (10−10, 5 × 10−10 or 5 × 10−9 g ml−1; equivalent to 2, 10 or 100 U ml−1, or to 6, 30 or 300 pM; Sigma) or IL-1B (5 × 10−13–5 × 10−9 g ml−1; equivalent to 30 fM–300 pM; R&D Systems Ltd, Abingdon, U.K.) was added for a further 4 h under static conditions; (ii) HUVEC were cultured under static conditions for 24 h and then exposed to shear stress of 0.3 Pa, 1.0 or 2.0 Pa for 24 h. TNFα or IL-1B was then added and flow continued upto 4 h. Paired, control, static microslides attached to the third arms of each dish were exposed to identical recirculated medium for identical periods. When comparing potency of TNFα and IL-1B, it may be remembered that they have approximately equal molecular weights (∼17 kDa) in their monomeric forms.

In chosen experiments, monoclonal antibodies (mAb) against P-selectin (mAb G1, 50 μg ml−1; gift of Rodger McEver, University of Oklamhoma, U.S.A.) or E-selectin (ENA2 F(ab')2, 1 μg ml−1; Bradshaw Biologicals, Chepshet, U.K.) were added to HUVEC with the cytokines for the last 20 min before adhesion assay. These antibodies have been effective in blocking adhesion in our previous studies (Buttrum et al., 1993; Rainger et al., 1996; Bahra et al., 1998). In other experiments, nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA; 5 μM) and indomethacin (10 μM; both Sigma) were added to HUVEC cultures along with IL-1B, to inhibit lipoxygenase and cycloxygenase pathways (Ibe et al., 1989).

Isolation of neutrophils

Blood was collected from healthy volunteers into K2EDTA (Sarstedt Ltd, Leicester, U.K.) and used within 2 h of venepuncture. Neutrophils were isolated as described (Rainger et al., 1995) and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mM Ca2+, 0.5 mM Mg2+, 0.15% culture-tested bovine serum albumin (Sigma) and 5 mM glucose (PBS/BSA) at 106cells ml−1. In chosen experiments, monoclonal antibodies against L-selectin (either clone SK11, 5 μg ml−1; Becton Dickinson Ltd, Oxford, U.K.; or TQ1, 5 μl ml−1; Beckman Coulter Ltd, High Wycombe, U.K.), CD18 (6.5E, 10 μg ml−1; gift of Martyn Robinson, Celltech Group plc, U.K.), CXC-receptor 1 or CXC-receptor-2 (9H1 or 10H2, respectively, 10 μg ml−1; gift of Dr K. Jim Kim, Genentech Inc., San Fransisco, U.S.A.; or 501 or 19, respectively, 2 μg ml−1; Biosource International Inc., Camarillo, CA, U.S.A.) were added to neutrophils for 20 min before adhesion assay. Studies of adhesion to TNFα-treated HUVEC were carried out using 9H1 and 10H2 (Luu et al., 2000). Studies with IL-1B-treated HUVEC were started with the same antibodies (2 experiments), but due to shortage of supply, we switched to 501 and 19 for three further experiments. Results were similar with either pair of antibodies. In some experiments, neutrophils were treated with the platelet-activating factor receptor (PAF-R) antagonist YM264 (10−4M; Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tsukuba, Japan) for 3 min before assay. These agents have been effective in blocking function in our previous studies (Buttrum et al., 1993; Rainger et al., 1995; 1998; Bahra et al., 1998).

Adhesion and migration of flowing neutrophils

Adhesion assays were performed as previously described (Rainger et al., 1995; Bahra et al., 1998; Luu et al., 1999). Microslides containing confluent HUVEC were viewed by phase contrast video microscopy during perfusion of a 4-min bolus of neutrophils and subsequent washout with phosphate-buffered saline with bovine serum albumin (PBS/BSA), all at a flow rate equivalent to a wall shear stress of 0.1 Pa. This wall shear stress is adequate to ensure that binding to HUVEC requires selectin expression, and cannot occur directly through integrin-mediated adhesion (Rainger et al., 1995; Bahra et al., 1998). Videomicroscopic recordings were analysed offline using a computerised image analysis system (ImagePro; DataCell Ltd, Finchampstead, U.K.). Adherent cells were easily distinguished from non adherent cells, visible only as faint streaks. After 5 min of washout, adherent cells were classified as either: (i) rolling slowly over the surface (velocity ∼5–10 μm s−1); (ii) activated on the surface (phase bright, and stationary or migrating slowly); (iii) transmigrated, (phase dark and migrating at ∼10–15 μm min−1 under the HUVEC) (Luu et al., 1999). In addition, the total number of adherent neutrophils was counted (rolling adherent plus activated plus transmigrated), and corrected per mm2 per 106 cells perfused.

Initial characterisation of dose responses to IL-1B and TNFα were carried out using culture medium containing human serum. In later studies, we switched to medium containing fetal calf serum plus epidermal growth factor, to avoid problems of supply of human AB serum. However, adhesion and migration of neutrophils on HUVEC treated with TNFα or IL-1B were similar using either medium, and data have been pooled where particular responses were studied with both media. All the studies of effects of culture under flow, using TNFα or IL-1B, were carried out using the same, later medium. In the early studies, we also studied adhesion after short treatments with TNFα and IL-1B. As previously reported (Bahra et al., 1998), approximately 60–90 min of TNFα treatment was required before neutrophil adhesion could be observed. In the case of IL-1B treatment, adhesion after 30 min treatment was not above that found for unstimulated HUVEC, but at 60 min adhesion rose to about half the level seen at 4 h. All cytokine treatments reported subsequently here were of 4 h duration unless stated otherwise.

Evaluation of gene expression by RT–PCR

RNA was extracted from HUVEC within microslides and reverse transcription of single-stranded cDNA and PCR were conducted as described (Sheikh et al., 2003). Primers and PCR reaction conditions for β-actin, interleukin-8 (IL-8; CXC-ligand 8), E-selectin and P-selectin were as described (Sheikh et al., 2003). Primers and PCR conditions for growth-related oncogene-α (GRO-α; CXC-ligand 1) and epithelial neutrophil-activating peptide 78 (ENA-78; CXC-ligand 5) were from BD Clontech U.K. (Basingstoke, U.K.). Primers and PCR conditions for ICAM-1 were from R&D Systems Europe Ltd (Abingdon, U.K.). Primers for transcription factors of the Rel family: Rel-A (p65), Rel-B (p68), C-Rel, (p75), NF-κB1 (p105/p50) and NF-κB2 (p100/p52) were designed in house using CLONE (Scientific and Educational Software) and synthesised by Alta Bioscience (Birmingham United Kingdom). The primer sequences and PCR conditions are listed in Table 1. Amplified products were analysed on 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide, band density measured using a scanning densitometer, and values were expressed relative to those for β-actin in the same sample.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions for NFκB/Rel family members

| Gene | Primer sequence | Annealing temperature (°C) | Amplified product size (bp) | Genbank accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rel-A | Fw. 5′-TGCGGACATGGACTTCTCAG-3′ | 54 | 503 | L19067 |

| P65 | Rv. 5′-CAA TGC CAG TGC CAT ACA GG-3 | |||

| Rel-B | Fw. 5′-CTG CTT CCA GGC CTC ATA TC-3′ | 57 | 704 | XM_008848 |

| p68 | Rv. 5′-CCA GCA TGG TGA AGA GTG TG-3′ | |||

| c-Rel | Fw. 5′-TCA ATG GCA CCT CTG CCT TC-3′ | 52 | 441 | X75042 |

| p75 | Rv. 5′-ATT GGC GCC TGC TGA CAT AC-3′ | |||

| NFκB1 | Fw. 5′-GAT GGC ACT GCC AAC AGA TG-3′ | 54 | 501 | M58603 |

| p50/p105 | Rv. 5′-AGA GCT GCT TGG CGG ATT AG-3′ | |||

| NFκB2 | Fw. 5′-CAA CTC CGG ATC TCG CTC TC-3′ | 56 | 713 | X61498 |

| p52/p100 | Rv. 5′-CGC AGC CGC ACT ATA CTC AG-3′ |

Fw., forward; Rv., reverse; bp, base pairs.

ELISA for activated transcription factors

The concentration of activated nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)/Rel family members in nuclear extracts was measured using a TransAM NF-κB kit (Active Motif, CA, U.S.A.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. HUVEC nuclear proteins were extracted and retrieved using a nuclear lysis buffer and centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 120 s. Protein concentration was measured by Bradford assay. In total, 1 μg of nuclear protein in coating buffer containing herring sperm DNA was applied to each well in the ELISA plate, which was coated with oligonucleotide containing an NF-κB consensus binding site, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature (RT) on a shaker. The plate was washed three times with washing buffer, and polyclonal rabbit primary antibodies against each of the NF-κB/Rel family was added to separate wells. After incubation for 1 h at RT, and another three washes, the plate was incubated for another hour at RT with horse radish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The plate was washed four times and 100 μl developing solution was applied to each well and incubated for 2–10 min at RT in the dark. When sufficient colour had developed, 100 μl stop solution was added to each well, and the absorbance of wells at 450 nm wavelength was measured in a plate reader. Absorbance in blank wells (without sample added, but with appropriate antibodies) was deducted from each of the corresponding samples. Nuclear extract (1 μg) from Raji cells was supplied by the manufacturers, and used as positive control for each primary antibody.

Immunofluorescence and flow cytometry

HUVEC in microslides were fixed with 0.5% formadehyde at 4°C for 2.5 min and washed with PBS/BSA. Mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) against E-selectin (clone 1.2B6) or mouse IgG control (all from DakoCytomation Ltd, Ely, U.K.) was diluted to 0.3 μg ml−1 in PBS containing 2% normal goat serum, injected into microslides and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Monolayers were washed with PBS/BSA and incubated for 1 h with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (DakoCytomation Ltd). The monolayers were treated with trypsin/EDTA at room temperature for 4 min and the cells were flushed from the microslide and washed with PBS/BSA. The ratio of median fluorescence intensities for E-selectin vs IgG control was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Ltd, Oxford, U.K.).

Statistical analysis

Effects of varying cytokine dose, shear stress or multiple treatments were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where appropriate, samples treated with individual antibodies or inhibitors were compared to untreated controls by paired t-test. All tests were performed using the computer program Minitab (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, U.S.A.).

Results

Neutrophil behaviour on HUVEC treated with TNFα or IL-1B in static cultures

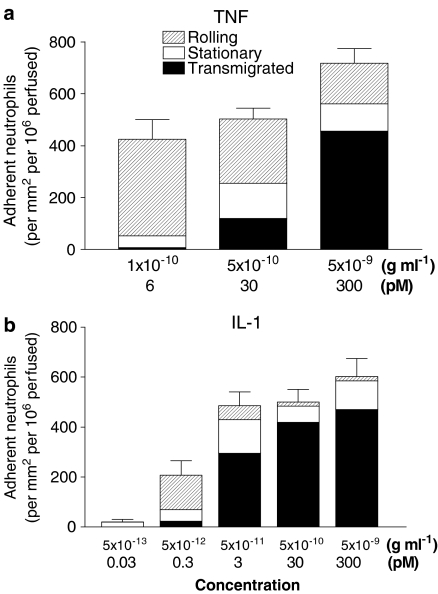

Neutrophils adhered efficiently to HUVEC which had been cultured with TNFα under conventional static conditions (Figure 1a). Increasing the concentration of TNFα from 10−10 to 5 × 10−9 g ml−1 (equivalent to 2–100 U ml−1, or 6–300 pM) had a modest effect on the level of adhesion, but markedly increased the proportion of adherent cells that migrated through the endothelial monolayer, and decreased the proportion rolling (Figure 1a). Adhesion of neutrophils to HUVEC that had been treated with IL-1B followed a similar pattern, with adhesion saturating at a low concentration (∼5 × 10−11 g ml−1, or 3 pM) and increasing little when the dose was increased a 100-fold further (Figure 1b). However, except at the lowest dose of 5 × 10−12 g ml−1 (0.3 pM), there was a consistently high proportion of adherent cells that transmigrated and few that rolled. In addition, IL-1B was able to induce adhesion and migration at lower concentration than TNFα. Thus, both cytokines have similar ability to induce capture, immobilisation and migration of flowing neutrophils, although IL-1B appears to be more potent at equal molar concentrations.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the adhesive behaviour of flowing neutrophils perfused over HUVEC treated with different concentrations of (a) TNFα or (b) IL-1B. The number of adherent neutrophils is shown for cells rolling on the HUVEC, stationary on the monolayer surface or transmigrated under it. Data are means from three to four experiments for TNFα, and eight to 13 experiments for IL-1B. S.e.m. are shown for the total adhesion.

Effects of culture under flow on functional responses of HUVEC to TNFα or IL-1B

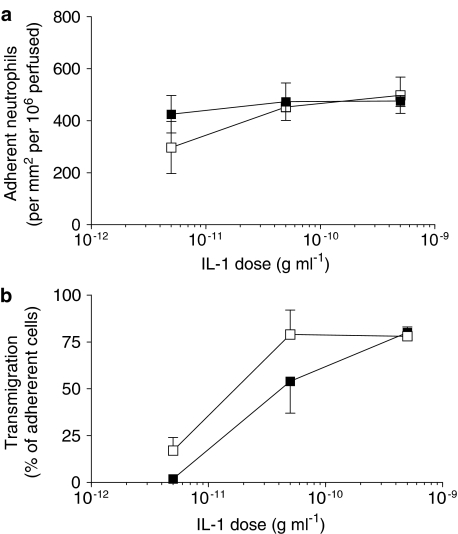

We recently reported that culture of endothelial cells under conditions of flow markedly altered their response to a range of doses of TNFα (Sheikh et al., 2003). After culture under low shear stress (0.3 Pa), there was modest but significant reduction in the ability to capture flowing neutrophils, but a much greater reduction in transmigration of the captured cells. At higher shear stresses (1.0 or 2.0 Pa), the ability of TNFα-treated endothelial cells to capture flowing neutrophils was greatly reduced. Figure 2 shows the effects of culture at 0.3 Pa for 24 h on subsequent responses of endothelial cells to different doses of IL-1B, judged by the numbers of neutrophils adhering from flow and the proportion of the adherent cells going on to transmigrate. Adhesion was not significantly modified by culture under flow at this relatively low shear stress for any of the concentrations of IL-1B tested, compared to static cultures (Figure 2a). Flow culture did not decrease the efficiency of transmigration on IL-1B-treated HUVEC, but showed a slight tendency to increase it at the lower concentrations of IL-1B (Figure 2b). Next, HUVEC were exposed to a range of increasing stresses (0.3, 1.0 or 2.0 Pa) and then treated with a single dose of IL-1B (5 × 10−10 g ml−1). The levels of adhesion to HUVEC treated with IL-1B remained essentially constant regardless of the shear stress during culture (Figure 3). In addition, the efficiency of transmigration varied little for the IL-1B-treated HUVEC regardless of the shear stress during culture (e.g., 73% of adherent neutrophils transmigrated for static cultures whereas 65% transmigrated for cultures exposed to shear stress; data pooled from three experiments at each shear stress). We also re tested the effects of culture at two shear stresses (0.3 and 2.0 Pa) on responses of HUVEC to TNFα at a single dose (5 × 10−9 g ml−1). Consistent with our previous report (Sheikh et al., 2003), compared to static culture controls, the proportion of adherent neutrophils transmigrating through the low shear cultures was reduced by 55±15% (mean±s.e.m. from four experiments; P<0.05), while adhesion to the high shear cultures was reduced by 69±8% (mean±s.e.m. from three experiments; P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect of exposing HUVEC to flow on their response to different concentrations of IL-1B, assessed by (a) the number of adherent neutrophils, or (b) the percentage of adherent neutrophils transmigrating. HUVEC were cultured static (▪) or exposed to a shear stress of 0.3 Pa for 28 h (□), with IL-1B added for the last 4 h, followed by flow-based adhesion assay. Data are mean±s.e.m. from three experiments at each concentration of cytokine. ANOVA showed no significant effect of culture conditions on adhesion, and borderline significance for transmigration (P=0.07).

Figure 3.

Effect of exposing HUVEC to flow at different shear stresses on their response to IL-1B, assessed by the number of adherent neutrophils. HUVEC were cultured static (▪) or exposed to flow at a shear stress of 0.3, 1.0 or 2.0 Pa for 28 h (□) with 5 × 10−10 g ml−1 IL-1B added for the last 4 h, followed by flow-based adhesion assay. Data are mean±s.e.m. from three experiments at each stress. ANOVA showed no significant effect of the level of stress on adhesion.

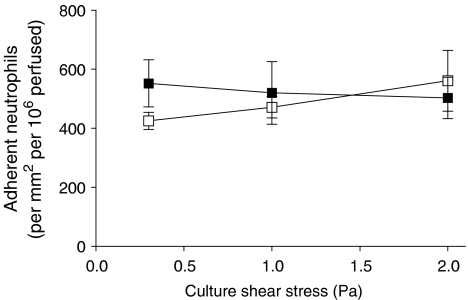

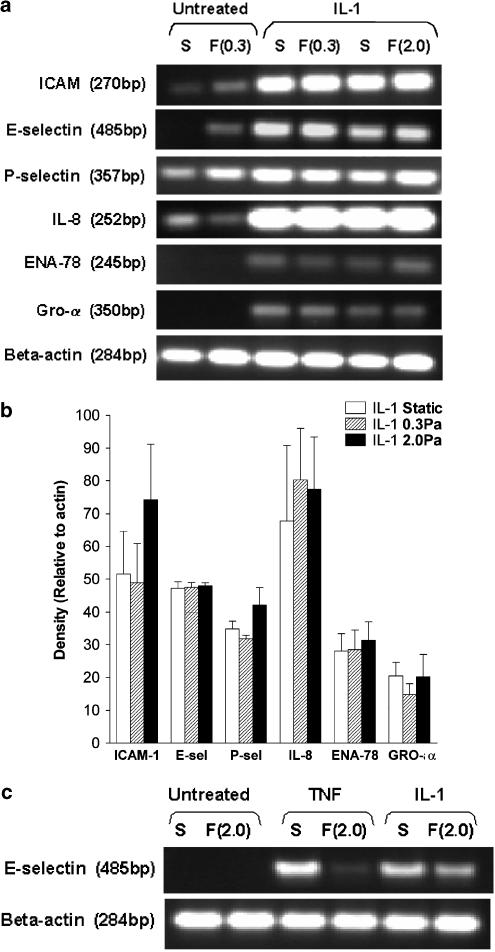

Effects of culture under flow on expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines

Levels of mRNA for adhesion molecules and chemokines were compared for HUVEC treated with cytokines under static or flow conditions. In our previous report (Sheikh et al., 2003), culture under flow suppressed expression of E-selectin, IL-8 and GRO-α induced by TNFα, while levels of mRNA for ICAM-1 or for P-selectin were not affected by flow. Here, expression of ICAM-1, E-selectin, IL-8, GRO-α levels and ENA-78 were all upregulated by IL-1B treatment. However, culture of HUVEC at 0.3 or 2.0 Pa had no consistent effects on the levels of expression of any of these proteins compared to static cultures (Figure 4a,b). Since E-selectin appeared to be the major adhesion receptor regulated by shear exposure in the TNFα model, direct comparisons were made between responses to TNFα and IL-1B for this receptor. As expected, both cytokines upregulated expression of E-selectin at the mRNA level in static cultures, but culture at 2.0 Pa only inhibited upregulation in response to TNFα (Figure 4c). We also checked surface expression of E-selectin on HUVEC after IL-1 treatment. Immunofluoresence labelling and flow cytometry showed that while treatment with IL-1B greatly increased the surface expression of E-selectin in static cultures (median fluoresence intensity relative to unstimulated control=21.4±5.2; mean±s.e.m. from four experiments), this expression was not reduced by exposure to flow. There was a further increase of 7 or 20% when IL-1B-treated HUVEC were cultured at 0.3 or 2.0 Pa, respectively (means from two experiments in each case).

Figure 4.

Effect of exposing HUVEC to flow on their expression of genes for adhesion receptors and chemokines. (a) Trans-illuminated ethidium bromide gels are shown for DNA amplified by RT–PCR from mRNA extracted from HUVEC, which were cultured for 26 h under static conditions (S) or exposed to shear stress of 0.3 or 2 Pa ((F0.3), F(2.0), resepctively). HUVEC were either unstimulated or IL-1B (5 × 10−10 g ml−1) was added for the last 2 h. Actin is shown as a loading control unmodified by treatment. (b) Densitometry of DNA bands obtained under the conditions as described in (a). Data are expressed relative to values for β-actin and are mean±s.e.m. from three experiments under each condition. (c) Direct comparison of DNA for E-selectin amplified by RT–PCR from mRNA extracted from HUVEC, which were cultured for 26 h under static conditions (S) or exposed to shear stress of 2 Pa (F(2.0)) with IL-1B (5 × 10−10 g ml−1) or TNFα (5 × 10−9 g ml−1) added for the last 2 h. The results are representative of four experiments.

Effects of culture under flow on expression and activation of transcription factors

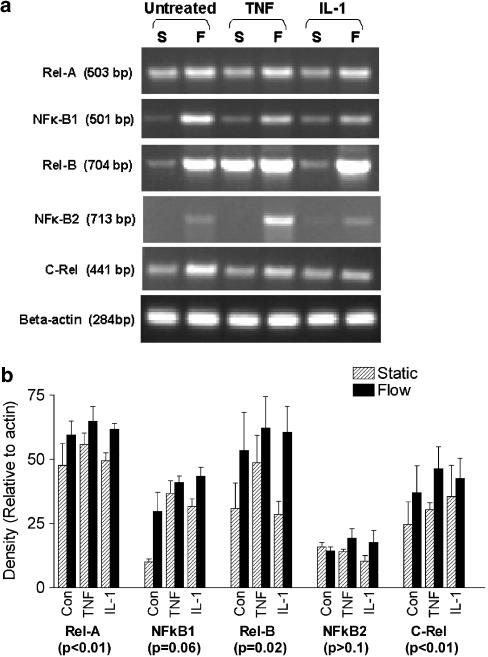

To probe possible reasons for the differential effects of shear stress on TNFα and IL-1B, we analysed levels of mRNA for each of the members of the NF-κB/Rel family of transcription factors (NF-κB1, NF-κB2, Rel-A, Rel-B, c-Rel). Direct comparisons were made of unstimulated, TNFα-treated and IL-1B treated HUVEC, cultured under static conditions or at a shear stress of 2.0 Pa. All of the family members were consistently detectable, except mRNA for NF-κB2 which varied markedly between cultures and treatments. The following trends were found (Figure 5): (i) levels of expression were generally upregulated by exposure to shear stress for 24 h before cytokines were added; (ii) cytokine treatments themselves had little effect on expression levels; (iii) effects of shear stress were similar for untreated HUVEC and for HUVEC treated with either cytokine.

Figure 5.

Effect of exposing HUVEC to flow on their expression of genes for transcription factors of the NF-κB/Rel family. (a) Trans-illuminated ethidium bromide gels are shown for DNA amplified by RT–PCR from mRNA extracted from HUVEC, which were cultured for 26 h under static conditions (S) or exposed to shear stress of 2.0 Pa (F), with TNFα (5 × 10−9 g ml−1) or IL-1B (5 × 10−10 g ml−1) added for the last 2 h. Actin is shown as a loading control unmodified by treatment. (b) Densitometry of DNA bands obtained under conditions as described in (a). Data are mean±s.e.m. from four experiments under each condition. ANOVA showed a significant effect of flow culture on expression of the transcription factors overall (P<0.01). The results of ANOVA for the effects of flow on individual transcription factors are shown in brackets below each label in the graph.

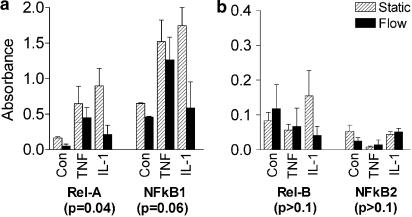

Since shear clearly did not impair expression of these transcription factors, and nor did the cytokines have differential effects, we evaluated transcription factor activation in nuclear extracts using a commercial ELISA. Signals were highest for the main Rel-family dimer members NF-κB1 and RelA (often simplify classified as NF-κB), and cytokine treatment consistently increased nuclear translocation of this activated transcription factor (Figure 6). Culture under flow reduced activation of NF-κB1 and RelA compared to static cultures, for unstimulated or cytokine-stimulated cultures (Figure 6a). However, this effect of flow on activation was at least as great for IL-1B-treated HUVEC as for TNFα-treated HUVEC. The transcription factors NF-κB2 and RelB consistently gave small signals in nuclear extracts, but there was little effect of cytokine treatment or of culture under shear (Figure 6b). Activation of cRel was undetectable in all experiments, although positive control extracts from Rami cells did yield a signal. Thus, while flow suppressed transcription factor activation, an increase over basal levels still occurred with cytokines, and the effect could not obviously explain why functional responses to TNFα but not IL-1B were inhibited by flow culture.

Figure 6.

Effect of exposing HUVEC to flow on levels of activated transcription factors of the NF-κB/Rel family found in nuclear extracts. Absorbances from ELISA are shown for extracts from HUVEC, which were cultured for 24 h under static conditions (Static) or exposed to shear stress of 2 Pa (Flow) before TNFα (5 × 10−9 g ml−1) or IL-1B (5 × 10−10 g ml−1) was added for 45 min under the same conditions. The vertical scale in (b) has been expanded compared to (a), because of the lower levels of activation of Rel-B and NF-κB2. Data are mean±s.e.m. from three experiments under each condition. ANOVA showed a significant effect of flow culture on activation of the transcription factors overall (P<0.01). The results of ANOVA for the effects of flow on individual transcription factors are shown in brackets below each label in the graph.

Mechanisms of neutrophil adhesion and migration on HUVEC treated with TNFα or IL-1B

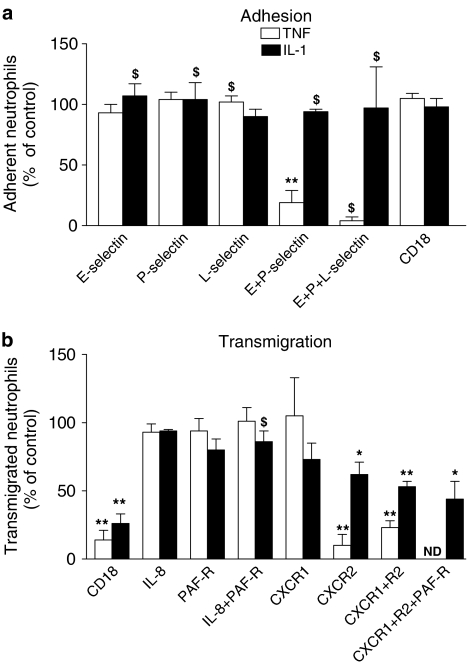

In order to explore further the differences in neutrophil recruitment induced by the two cytokines, we used function-blocking agents to investigate the mechanisms of adhesion and migration on HUVEC cultured under static conditions. In Figure 7, results for HUVEC treated with TNFα are summarised, derived from our previously reported studies (Bahra et al., 1998; Luu et al., 2000; Luu et al., 2003). In addition, new data for the effects of the same agents are shown, for HUVEC treated with IL-l. In the case of TNFα treatment, blockade with antibodies against endothelial selectins indicated that capture of flowing neutrophils was mediated by E- and P-selectin acting together (Figure 7a), but there was no consistent effect of blockade of neutrophil L-selectin. Blockade of β2-integrins did not affect the total number of adherent neutrophils (Figure 7a) but greatly inhibited migration through the endothelial monolayer (Figure 7b). Using the same antibodies with IL-1B-treated HUVEC, we found little effect on adhesion when E-, P- or L-selectin were blocked individually or in combinations (Figure 7a). Owing to others' work showing a role for L-selectin in binding to IL-1B-treated HUVEC (Smith et al., 1991; Abbassi et al., 1993), we carried out experiments with two different antibodies against L-selectin (SK11 and TQ-1), but in either case found only minor reduction in adhesion (∼10%). When we blocked β2-integrin CD18, the level of adhesion remained unaltered (Figure 7a), but percentage of adherent cells migrating was again greatly reduced (Figure 7b). Thus, while migration on TNFα- or IL-1B-treated HUVEC was supported through β2-integrin as expected (Smith et al., 1991; Bahra et al., 1998), blockade of capture receptors active in the TNFα model had little effect in the IL-1B model. We also examined effects of antibodies against selectins after only 1 h treatment with IL-1B (when adhesion was about half the level found after 4 h), but again found no effects (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Effects of function blocking agents on (a) adhesion and (b) transendothelial migration of neutrophils on HUVEC treated with TNFα (5 × 10−9 g ml−1) or IL-1B (5 × 10−10 g ml−1) for 4 h before assay. In (a), function-blocking antibodies against individual receptors (CD18, E-selectin, P-selectin or L-selectin) were used alone or in combinations. In (b) function-blocking antibodies against CD18, IL-8, CXCR-1 or CXCR2 were used, or a competitive inhibitor of PAF-R (YM264) was used, alone or in combinations. Data are from three to five experiments, except those marked $ where n=2. Data are mean±s.e.m., except where n=2, where date are mean±range. Data for L-selectin blockade in experiments with IL-1B-treated HUVEC are pooled from experiments with two different antibodies against L-selectin: clone SK11 (n=2) and TQ-1 (n=3). Antibody SK11 was used in combination treatments. ND=not done. ANOVA showed that in (a), the effects of treatment were significant for TNFα-treated HUVEC (P<0.01) but not for IL-1B-treated HUVEC. In (b) the effects of treatment were significant for both TNFα-treated and IL-1B-treated HUVEC (P<0.01 in each case). *=P<0.05, **=P<0.01 compared to untreated control by paired t-test. Data for effects on recruitment to TNFα-treated HUVEC are derived from our previously published reports (Bahra et al., 1998; Luu et al., 2000; 2003).

In studies with TNFα-treated HUVEC, the signal for neutrophil activation, which induced conversion to stable adhesion and subsequent migration, was transduced mainly through the chemokine receptor CXCR-2. Blockade of this receptor reduced transmigration by about 90% (Figure 7b). Blockade of PAF-Rs on neutrophils had no detectable effects, nor did antibody neutralisation of IL-8 (Figure 7b). In the case of IL-1B-treated HUVEC, blockade of CXCR1 caused a slight but non significant reduction in transmigration, and blockade of CXCR2 had a greater and significant effect (Figure 7b). Blockade of both had the greatest effect on transmigration, but inhibition of migration was still not complete. In separate experiments, neutralisation of IL-8 had no significant effect on transmigration, while treatment of neutrophils with a PAF-R antagonist caused a small, consistent reduction which did not reach statistical significance (Figure 7b). When PAF-R antagonist was subsequently combined with mAb against CXCR1 and CXCR2, migration was reduced further (Figure 7b), but there was still a proportion of neutrophils able to transmigrate. Thus, activation of neutrophils occurred dominantly through CXCR2 for TNFα-treated HUVEC but appeared to occur through CXCR1, CXCR2, PAF-R and possibly other unknown route(s) for IL-1B. In separate experiments, we inhibited lipoxygenase and cycloxygenase pathways in HUVEC using NDGA and indomethacin during IL-1B treatment, but this did not reduce the proportion of neutrophils transmigrating (11±7% reduction; mean±s.e.m. from three experiments).

Discussion

These studies show that TNFα and IL-1B are both highly effective at inducing endothelial cells to support the capture, activation and migration of flowing neutrophils. However, while responses to IL-1B were similar irrespective of the shear stress at which HUVEC were cultured, responses to TNFα were down regulated by exposure to shear. This was true at the levels of gene expression and adhesive function. Interestingly, expression and activation of transcription factors of NF-κB/Ref family were both modified by culture under flow, but there were no differential effects between IL-1B and TNFα. In addition, dissection of mechanisms underlying recruitment of neutrophils indicated that: E- and P-selectin supported neutrophil capture by endothelial cells treated with TNFα, but other receptor(s) were also involved for IL-1B-treated HUVEC; IL-1B caused more efficient transendothelial migration; although β2-integrins were clearly required for migration with either cytokine, neutrophil activation appeared to occur through CXCR1, CXCR2 and PAF-R for IL-1B, but dominantly through CXCR2 for TNFα.

We previously found no evidence of changes in expression of TNFα-receptor 1 or 2 (TNFR1,2) on HUVEC exposed to shear stress (Sheikh et al., 2003). Thus, the differing effects of shear stress on endothelial responses to IL-1B and TNFα suggest differential sensitivity to shear in the downstream signalling or gene transcription pathways after cytokines ligate their cognate receptors. TNFR 1 and 2 and the IL-1B receptor type I initiate different signalling pathways, but both are able to activate the NF-κB and activating protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factors (Dinarello, 1996; Eder, 1997; Wajant et al., 2003). Berk and co-workers have shown that exposure to shear stress can inhibit TNFα-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (Surapisitchat et al., 2001) and of TNFα-receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF-2) (Yamawaki et al., 2003) which lie upstream of transcription factor activation. Other studies have shown that shear can upregulate expression of TRAF-3, which is an inhibitor of TNFR family signalling (Urbich et al., 2001). However, while our studies show that both basal and cytokine-induced levels of NF-κB activation are reduced by culture under shear, both TNFα and IL-1B did induce marked activation in sheared cultures. These results suggest that upstream signalling from both cytokines was intact, or at least similarly impaired. There was no differential response that could explain why reduction in functional responses occurred for TNFα and not IL-1B. This raises the possibility that the critical influence of shear occurs at the level of regulation of gene transcription rather than transcription factor activation. Interestingly, recent studies indicate that the transcription factor Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) is upregulated by shear stress (Dekker et al., 2002; SenBanerjee et al., 2004) This transcription factor may reduce NF-κB-mediated responses by competition for a necessary co factor, p300/CBP (SenBanerjee et al., 2004). However, in studies where KLF2 was upregulated by over expression of the murine homolog in HUVEC, responses to both IL-1B and TNFα were reduced (SenBanerjee et al., 2004). We have confirmed upregulation of mRNA for KLF-2 in our sheared endothelial cultures using RT–PCR (data not shown). Further studies will be needed to test whether the endogenous human factor is differentially regulated by TNFα or IL-1B, or able to induce differential changes in their functional responses.

Our inability to block adhesion to IL-1B-treated HUVEC with antibodies against selectins is puzzling, even though there was clear upregulation of E-selectin mRNA and surface expression as expected. The same antibodies against selectins have been effective in our previous studies in other adhesion models (Buttrum et al., 1993; Rainger et al., 1995; Bahra et al., 1998; Rainger et al., 1998). Others showed that blockade of L-selectin or E-selectin caused partial inhibition of adhesion of neutrophils to IL-1B-treated HUVEC in static or flow-based assays (Bevilacqua et al., 1987; Kishimoto et al., 1991; Smith et al., 1991; Abbassi et al., 1993; Jones et al., 1996), although the effects were not additive (Kishimoto et al., 1991). It may be relevant that in their flow-based studies (Smith et al., 1991; Abbassi et al., 1993; Jones et al., 1996), Smith et al. used a wall shear stress about twice that used here. It is possible that their results were more influenced by secondary tethering between neutrophils, a process where the first-bound cells assist attachment of subsequently arriving cells through L-selectin (Walcheck et al., 1996). In our experience, it is more clearly evident at higher shear stress, where trains of adherent neutrophils can be seen to develop on adhesive surfaces (unpublished observations).

Neither previous studies, nor this one, have achieved near-complete inhibition of adhesion of neutrophils to IL-1B-treated HUVEC by using antibodies against known adhesion molecules. It is likely, therefore, that several receptors combine in capture of neutrophils to IL-1B-stimulated HUVEC. In our previous studies of adhesion to TNFα-treated HUVEC (Bahra et al., 1998), we found little effect of individual blockade of P-selectin or E-selectin, but neutrophil adhesion was greatly reduced when both were blocked. Thus, when combinations of receptors are present, it can be difficult to define their individual roles unless effective agents against all are available and combined. In the case of IL-1B-treated HUVEC, this and previous studies (e.g., Smith et al., 1991; Jones et al., 1996) do agree that unknown receptor(s) (i.e., additional to known selectins) contribute to the capture of flowing neutrophils. Differences in the effects of blocking E-selectin in the different studies may depend on relative levels of expression of the different receptors under the specific culture conditions used in them.

The situation with regard to endothelial-presented activating agents is not completely clear either. It should be emphasised that TNFα is no longer present in our system during assay, so that it should have no effects on neutrophils directly. This is evidenced by the highly effective blockade of migration by antibody against CXCR2, and differs from the situation where TNFα is added in vivo where some effect may occur via neutrophil activation by TNFα (Young et al., 2002). In addition to CXCR-mediated activation, PAF was active in promoting neutrophil migration for IL-1B-treated HUVEC. This agrees with studies showing pro migratory effects of PAF in IL-1B-treated mice (Young et al., 2002). Others have indicated that PAF and IL-8 are effective in promoting migration through TNFα-treated monolayers (Kuijpers et al., 1992; Smart & Casale, 1994), but this was in static assays where released agents may build up and for instance, PAF may be released from neutrophils. We found no evidence of a role for PAF in the TNFα model (Bahra et al., 1998), but its action in the IL-1B model may explain the greater efficiency of migration compared to TNFα. In HUVEC treated with IL-1B, we found that mRNA for IL-8, Gro-α and ENA-78 were upregulated, while with TNFα the last was not detected. Neutralisation of IL-8 alone was not effective in the TNFα or IL-1B models, although in our earlier studies, it did reduce neutrophil activation on HUVEC that had been exposed to hypoxia and reoxygenation (Rainger et al., 1995). Thus, the exact combination of CXC-chemokines activating the neutrophils on the cytokine-treated HUVEC remains uncertain, but may differ for IL-1B compared to TNFα.

The studies presented here have implications for our understanding of physiological or pathological inflammatory responses, and treatment of the latter. They support, in human systems, the findings of Nourshargh and co-workers (Thompson et al., 2001; Young et al., 2002), that neutrophil recruitment in mice treated with IL-1B or TNFα occur via different pathways. Our results suggest that an undescribed receptor may be involved in adhesion of human neutrophils to IL-1B-treated endothelium. One implication is that therapeutic strategies aimed at known receptors can be expected to have an efficacy that depends on the inflammatory stimulus. Evidently, specific anti-inflammatory approaches against adhesion molecules or against activatory/chemotactic agents cannot be expected to be effective in all conditions, although common pathways (e.g., through β2-integrins) may exist. The modulation of responses to cytokines by shear stress might explain variations in sensitivity of endothelial cells to inflammatory agents in different regions of the circulation. For instance, endothelial cells at branch points in arteries experience relatively low shear stress compared to near neighbours, and this may contribute to regional predeliction to development of atheromatous plaques (Caro et al., 1971; Ross, 1995). Nevertheless, our results suggest that the predisposing effects of low shear are likely to depend on which cytokines and growth factors are locally active. Thus, overall, clear definitions of the inflammatory agents and regulatory pathways acting in specific milieu are required to understand pathogenesis and to target interventions efficiently.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Programme Grant from the British Heart Foundation (No. RG/2000011) and a British Heart Foundation Non-Clinical Lectureship Award to GER (BS/97001).

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activating protein 1

- CXCR1

CXC-chemokine receptor 1

- ENA-78

epithelial neutrophil-activating peptide 78

- GRO-α

growth-related oncogene-α

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- IL-1B

interleukin-1β

- KLF2

Kruppel-like factor 2

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- PAF-R

platelet-activating factor receptor

- PBS/BSA

phosphate-buffered saline with bovine serum albumin

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor α

- TNFR

TNF-receptor

- TRAF-2

TNF-receptor-associated factor 2

References

- ABBASSI O., KISHIMOTO T.K., MCINTIRE L.V., SMITH C.W. Neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells. Blood Cells. 1993;19:245–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAHRA P., RAINGER G.E., WAUTIER J.L., LUU N.-T., NASH G.B. Each step during transendothelial migration of flowing neutrophils is regulated by the stimulatory concentration of tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Cell Adhes. Commun. 1998;6:491–501. doi: 10.3109/15419069809010797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEVILACQUA M.P., POBER J.S., MENDRICK D.L., COTRAN R.S., GIMBRONE M.A., JR Identification of an inducible endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:9238–9242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.9238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTTRUM S.M., HATTON R., NASH G.B. Selectin-mediated rolling of neutrophils on immobilized platelets. Blood. 1993;82:1165–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARO C.G., FITZGERALD J.M., SCHROTER R.C. Atheroma and arterial wall shear: observation, correlation and proposal of a shear-dependent mass transfer mechanism for atherogenesis. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. 1971;117:109–159. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1971.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COOKE B.M., USAMI S., PERRY I., NASH G.B. A simplified method for culture of endothelial cells and analysis of adhesion of blood cells under conditions of flow. Microvasc. Res. 1993;45:33–45. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1993.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEKKER R.J., VAN SOEST S., FONTIJN R.D., SALAMANCA S., DE GROOT P.G., VANBAVEL E., PANNEKOEK H., HORREVOETS A.J. Prolonged fluid shear stress induces a distinct set of endothelial cell genes, most specifically lung Kruppel-like factor (KLF2) Blood. 2002;100:1689–1698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINARELLO C.A. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DINARELLO C.A. The IL-1 family and inflammatory diseases. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2002;20:S1–S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDER J. Tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 1 signalling: do MAPKK kinases connect it all. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1997;18:319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBE B.O., FALCK J.R., JOHNSON A.R., CAMPBELL W.B. Regulation of synthesis of prostacyclin and HETEs in human endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;256:C1168–C1175. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.6.C1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES D.A., SMITH C.W., PICKER L.J., MCINTIRE L.V. Neutrophil adhesion to 24-h IL-1-stimulated endothelial cells under flow conditions. J. Immunol. 1996;157:858–863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KISHIMOTO T.K., WARNOCK R.A., JUTILA M.A., BUTCHER E.C., LANE C., ANDERSON D.C., SMITH C.W. Antibodies against human neutrophil LECAM-1 (LAM-1/Leu-8/DREG-56 antigen) and endothelial cell ELAM-1 inhibit a common CD18-independent adhesion pathway in vitro. Blood. 1991;78:805–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUIJPERS T.W., HAKKERT B.C., HART M.H., ROOS D. Neutrophil migration across monolayers of cytokine-prestimulated endothelial cells: a role for platelet-activating factor and IL-8. J. Cell Biol. 1992;117:565–572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.3.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNKEL E.J., JUNG U., LEY K. TNF-alpha induces selectin-mediated leukocyte rolling in mouse cremaster muscle arterioles. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:H1391–H1400. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.3.H1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LELKES P.I. Mechanical Forces and the Endothelium. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- LUSCINSKAS F.W., DING H., LICHTMAN A.H. P-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 mediate rolling and arrest, respectively, of CD4+ T lymphocytes on tumor necrosis factor alpha-activated vascular endothelium under flow. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1179–1186. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUU N.T., RAINGER G.E., BUCKLEY C.D., NASH G.B. CD31 regulates direction and rate of neutrophil migration over and under endothelial cells. J. Vasc. Res. 2003;40:467–479. doi: 10.1159/000074296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUU N.T., RAINGER G.E., NASH G.B. Kinetics of the different steps during neutrophil migration through cultured endothelial monolayers treated with tumour necrosis factor-alpha. J. Vasc. Res. 1999;36:477–485. doi: 10.1159/000025690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUU N.T., RAINGER G.E., NASH G.B. Differential ability of exogenous chemotactic agents to disrupt transendothelial migration of flowing neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2000;164:5961–5969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGEL T., RESNICK N., ATKINSON W.J., FORBES DEWEY C.J., GIMBRONE M.A.J. Shear stress selectively upregulates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in cultured human vascular endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1994;94:885–891. doi: 10.1172/JCI117410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLOFSSON A.M., ARFORS K.E., RAMEZANI L., WOLITZKY B.A., BUTCHER E.C., VON ANDRIAN U.H. E-selectin mediates leukocyte rolling in interleukin-1-treated rabbit mesentery venules. Blood. 1994;84:2749–2758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POBER J.S. Endothelial activation: intracellular signaling pathways. Arthritis Res. 2002;4 Suppl. 3:S109–S116. doi: 10.1186/ar576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAINGER G.E., BUCKLEY C., SIMMONS D.L., NASH G.B. Neutrophils rolling on immobilised platelets migrate into homotypic aggregates after activation. Thromb. Haemost. 1998;79:1177–1183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAINGER G.E., FISHER A., SHEARMAN C., NASH G.B. Adhesion of flowing neutrophils to cultured endothelial cells after hypoxia and reoxygenation in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. 1995;269:1398–1406. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.4.H1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAINGER G.E., WAUTIER M.-P., NASH G.B., WAUTIER J.-L. Prolonged E-selectin induction by monocytes potentiates the adhesion of flowing neutrophils to cultured endothelial cells. Br. J. Haematol. 1996;92:192–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSS R. Cell biology of atherosclerosis. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1995;57:791–804. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.004043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPATH R., KUKIELKA G.L., SMITH C.W., ESKIN S.G., MCINTIRE L.V. Shear stress-mediated changes in the expression of leukocyte adhesion receptors on human umbilical vein endothelial cells in vitro. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1995;23:247–256. doi: 10.1007/BF02584426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENBANERJEE S., LIN Z., ATKINS G.B., GREIF D.M., RAO R.M., KUMAR A., FEINBERG M.W., CHEN Z., SIMON D.I., LUSCINSKAS F.W., MICHEL T.M., GIMBRONE M.A., JR, GARCIA-CARDENA G., JAIN M.K. KLF2 is a novel transcriptional regulator of endothelial proinflammatory activation. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1305–1315. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEIKH S., GALE Z., RAHMAN M., RAINGER G.E., NASH G.B. Exposure to fluid shear stress modulates the ability of endothelial cells to recruit neutrophils in response to tumour necrosis factor-α: a basis for local variations in vascular sensitivity to inflammation. Blood. 2003;102:2828–2834. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHEIKH S., GALE Z., RAINGER G.E., NASH G.B. Methods for exposing multiple cultures of endothelial cells to different fluid shear stresses and to cytokines, for subsequent analysis of inflammatory function. J. Immunol. Methods. 2004;288:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHYY Y.J., HSIEH H.-J., USAMI S., CHIEN S. Fluid shear stress induces a biphasic response of human monocyte chemotactic protein 1 gene expression in vascular endothelium. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:4678–4682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMART S.J., CASALE T.B. TNF-alpha-induced transendothelial neutrophil migration is IL-8 dependent. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:238–245. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.3.L238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH C.W., KISHIMOTO T.K., ABBASSI O., HUGHES B., ROTHLEIN R., MCINTIRE L.V., BUTCHER E., ANDERSON D.C., ABBASS O. Chemotactic factors regulate lectin adhesion molecule 1 (LECAM-1)-dependent neutrophil adhesion to cytokine-stimulated endothelial cells in vitro. J. Clin. Invest. 1991;87:609–618. doi: 10.1172/JCI115037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SURAPISITCHAT J., HOEFEN R.J., PI X., YOSHIZUMI M., YAN C., BERK B.C. Fluid shear stress inhibits TNF-α activation of JNK but not ERK1/2 or p38 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: inhibitory crosstalk among MAPK family members. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:6476–6481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101134098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMPSON R.D., NOBLE K.E., LARBI K.Y., DEWAR A., DUNCAN G.S., MAK T.W., NOURSHARGH S. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1)-deficient mice demonstrate a transient and cytokine-specific role for PECAM-1 in leukocyte migration through the perivascular basement membrane. Blood. 2001;97:1854–1860. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOPPER JN, GIMBRONE MA., JR Blood flow and vascular gene expression, fluid shear stress as a modulator of endothelial phenotype. Mol. Med. Today. 1999;5:40–46. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- URBICH C., MALLAT Z., TEDGUI A., CLAUSS M., ZEIHER A.M., DIMMELER S. Upregulation of TRAF-3 by shear stress blocks CD40-mediated endothelial activation. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1451–1458. doi: 10.1172/JCI13620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON ANDRIAN U.H., HANSELL P., CHAMBERS J.D., BERGER E.M., TORRES F., I BUTCHER E.C., ARFORS K.E. L-selectin function is required for beta 2-integrin-mediated neutrophil adhesion at physiological shear rates in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;263:H1034–H1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAJANT H., PFIZENMAIER K., SCHEURICH P. Tumor necrosis factor signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:45–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALCHECK B., MOORE K.L., MCEVER R.P., KISHIMOTO T.K. Neutrophil–neutrophil interactions under hydrodynamic shear stress involve L-selectin and PSGL-1. A mechanism that amplifies initial leukocyte accumulation of P-selectin in vitro. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:1081–1087. doi: 10.1172/JCI118888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAWAKI H., LEHOUX S., BERK B.C. Chronic physiological shear stress inhibits tumor necrosis factor-induced proinflammatory responses in rabbit aorta perfused ex vivo. Circulation. 2003;108:1619–1625. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089373.49941.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOUNG R.E., THOMPSON R.D., NOURSHARGH S. Divergent mechanisms of action of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 1-beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in mouse cremasteric venules. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;137:1237–1246. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]