Abstract

The effects of flavoxate hydrochloride (Bladderon®, piperidinoethyl-3-methylflavone-8-carboxylate; hereafter referred as flavoxate) on voltage-dependent nifedipine-sensitive inward Ba2+ currents in human detrusor myocytes were investigated using a conventional whole-cell patch-clamp. Tension measurement was also performed to study the effects of flavoxate on K+-induced contraction in human urinary bladder.

Flavoxate caused a concentration-dependent reduction of the K+-induced contraction of human urinary bladder.

In human detrusor myocytes, flavoxate inhibited the peak amplitude of voltage-dependent nifedipine-sensitive inward Ba2+ currents in a voltage- and concentration-dependent manner (Ki=10 μM), and shifted the steady-state inactivation curve of Ba2+ currents to the left at a holding potential of −90 mV.

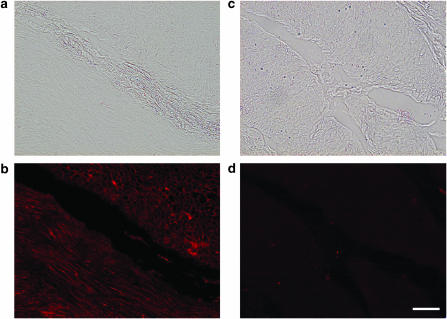

Immunohistochemical studies indicated the presence of the α1C subunit protein, which is a constituent of human L-type Ca2+ channels (CaV1.2), in the bundles of human detrusor smooth muscle.

These results suggest that flavoxate caused muscle relaxation through the inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels in human detrusor.

Keywords: Flavoxate, frequency of micturition, human detrusor myocytes, L-type Ca2+ channels, overactive bladder, spasmolytic agent

Introduction

Since the synthesis of flavoxate (piperidinoethyl-3-methylflavone-8-carboxylate hydrochloride) and its introduction to the urological field (Kohler & Morales, 1968), it has been widely used to treat urge frequency of micturition (i.e., urgency) for more than three decades (reviewed by Haeusler et al., 2002).

Flavoxate acts centrally to suppress the micturition reflex (Kaseda et al., 1975; Yoshimura et al., 1992). It has also been reported that flavoxate increases urinary bladder capacity, by modifying the micturition centre in the brain stem (Kimura et al., 1996), and that flavoxate inhibits cyclic AMP formation in rat striatal membranes of the brain through the stimulation of pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein-coupled receptors, which in turn suppresses isovolumetric rhythmic urinary bladder contraction (Oka et al., 1996). Thus, it has been generally thought that the beneficial effects of flavoxate for urinary frequency are through modulation of the central nervous system (CNS) control of micturition.

On the other hand, there are several reports that flavoxate causes a significant relaxation of urinary bladder smooth muscle precontracted by carbacol or electrical field stimulation (rat, Kimura et al. (1996); human, Uckert et al., 2000). These results strongly indicate that flavoxate possesses direct inhibitory effects on the detrusor muscle in addition to the actions on the CNS. However, the precise mechanisms involved in the flavoxate-induced detrusor relaxation remain elusive, and the target channels for flavoxate in the detrusor smooth muscle have not yet been identified.

It is well documented that voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels play an important role as a Ca2+ influx pathway, which initiates the contraction of smooth muscle cells (reviewed by McFadzean & Gibson, 2002). In the present experiments, therefore, we have first studied the effects of flavoxate on K+-induced tension using strips prepared from human urinary bladder. Second, we have investigated the effects of flavoxate on voltage-dependent nifedipine-sensitive Ba2+ currents (i.e., L-type Ca2+ currents or CaV1.2) in single freshly dispersed detrusor smooth muscle myocytes from human bladder, by use of whole-cell patch-clamp techniques.

Methods

Tension measurement and data analysis

Small segments of human detrusor was obtained from patients (a total of 27 patients, 39–81 years old; average age, 66 years old) with a stable urinary bladder who were generally undergoing cystectomy for bladder cancer after informed patient consent and with ethical approval from the Kyushu University Hospital Ethical Committee (Fukuoka, Japan). A segment of detrusor was excised and quickly transferred into modified physiological salt solution (PSS) as described previously (Teramoto et al., 2001). An initial tension equivalent to 0.5 g weight was applied to each human detrusor strip, which was then allowed to equilibrate for approximately 1 h until the basal tone became stable (36–37°C). Data were recorded on a Macintosh computer (Macintosh G4, Apple Computer, Tokyo, Japan), through ‘MacLab 3.5.6' (ADInstruments Pty Ltd, Castle Hill, Australia). The tension was expressed as mN mg−1 of tissue.

Cell preparation and patch-clamp experiments recording procedure

We used freshly dispersed single detrusor myocytes prepared from human urinary bladder. We employed the cell dispersion method previously described (the gentle tapping method; Teramoto & Brading, 1996). The set-up of the patch-clamp experimental system used was essentially the same as described previously (Teramoto et al., 2003). All experiments were performed at room temperature (21–23°C).

Data analysis

The whole-cell current data were low-pass filtered at 500 Hz (−3 dB) by an eight-pole Bessel filter (NF Electronic Instruments, Yokohama, Japan), sampled at 1 ms and analysed on a computer (Macintosh G4, Apple Computer, Tokyo, Japan) by use of the commercial software ‘Mac Lab 3.5.6' (ADInstruments Pty Ltd, Castle Hill, Australia). The dissociation constant for drug binding to the inactivated state of the channel could be estimated from the shift of the voltage-dependent inactivation curve and the concentration–response curve obtained at the resting state by using the following equation (Uehara & Hume, 1985):

where ΔVhalf is the amplitude of the shift of the voltage-dependence of the activation curve, k is a slope factor for the inactivation curve and [D] is the concentration of drug applied. Kinact and Krest are dissociation constants of flavoxate for the inactivated and the resting states of voltage-dependent Ba2+ channels, respectively.

Solutions and drugs

Modified PSS (mM): Na+ 140, K+ 5, Mg2+ 1.2, Ca2+ 2, Cl− 151.4, glucose 10, HEPES 10, titrated to pH 7.35–7.40 with Tris base. For recording voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents in whole-cell configuration, high caesium pipette solution contained (mM): Cs+ 130, tetraethylammonium (TEA+) 10, Mg2+ 2, Cl− 144, glucose 5, EGTA 5, ATP 5, HEPES 10/Tris (pH 7.35–7.40). Ba2+ 10 mM bath solution contained (mM): Ba2+ 10, TEA+ 135, Cl− 155, glucose 10, HEPES 10/Tris (pH 7.35–7.40). Cells were allowed to settle in the small experimental chamber (approximately 80 μl in volume). The bath solution was superfused by gravity throughout the experiments at a rate of 2 ml min−1. Flavoxate hydrochloride (kindly provided by Nippon Shinyaku, Kyoto, Japan) was prepared daily as 100 mM stock solutions in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). The rest of the chemicals were purchased from Sigma (Sigma Chemical K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The final concentration of DMSO was less than 0.3%, not affecting membrane currents.

Immunohistochemical studies

Tissue samples from human urinary bladder were embedded in OCT compound (Tissues-Tek, SAKURA, Tokyo, Japan) in disposable plastic tubes and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Sections were cut in a cryostat (Leica, CM3050 S, Tokyo, Japan) at a thickness of 6 μm and mounted on silane-precoated glass slides, then allowed to air dry at room temperature for approximately 30 min. Sections were fixed in cold acetone and washed thoroughly in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before staining. The tissue sections were treated in 3% nonfat milk (Bean Stalk Snow Co. Ltd, Sapporo, Japan) in PBS, and then reacted with the primary antibody, polyclonal rabbit anti-CaV1.2 (α1C) ACC-003 antibody (diluted at 1 : 400, Alomone Labs, Jelsalem, Israel; Péréon et al., 1998) at 4°C overnight. Sections were then washed for 3 × 5 min in PBS. Visualization was achieved by subsequent incubation in biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit IgG (Histofine secondary antibody, Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min, followed by phycoerythrin-labelled avidin–biotin complex reagent (Streptavidin–phycoerythrin, BD pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, U.S.A.) for 30 min at room temperature under dark conditions. Sections were then washed for 3 × 5 min in PBS. Coverslips were mounted onto slides by use of fluorescence mounting medium and slides viewed by fluorescent microscopy (Olympus BX51, Olympus Optical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Absorption test was performed by utilizing antiboby that had been preincubated with the control peptide antigen (residues 848–865 of rat α1C, P22002). Nonimmunized rabbit IgG was also used instead of primary antibody for a negative control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (two-factor with replication). Changes were considered significant at P<0.05 (*).

Results

Effects of flavoxate on K+-induced contraction

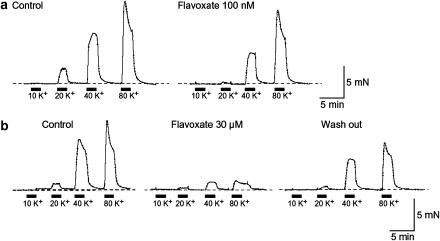

Tension measurement was performed to investigate the effects of flavoxate on K+ (10, 20, 40 and 80 mM)-induced contraction of human urinary bladder (Figure 1). Application of high K+ solution (2 min duration) caused a contraction in a concentration-dependent manner. Flavoxate (100 nM) suppressed the amplitude of K+-induced contraction. At 30 μM, flavoxate inhibited the K+-induced contraction over the full range of K+ concentrations from 20 to 80 mM. After approximately 30 min washout of flavoxate, the K+-induced contraction was partially recovered but did not return to the control level. Figure 2 summarizes these results. The relative value of each K+-induced contraction was obtained when the peak amplitude of 80 mM K+-induced contraction in the absence of flavoxate was normalized as one.

Figure 1.

Effects of flavoxate on K+-induced contraction (10, 20, 40 and 80 mM) of human detrusor strips. (a) K+-induced contraction in the absence (control) and presence of 100 nM flavoxate. (b) K+-induced contraction in the absence and presence of 30 μM flavoxate.

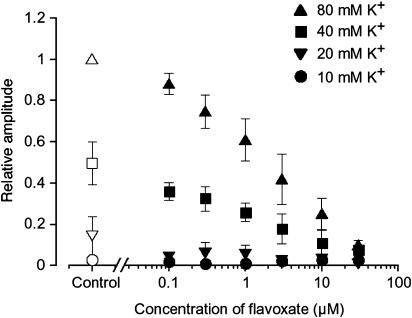

Figure 2.

Effects of flavoxate (⩾100 nM) on the peak amplitude of K+-induced contraction of human detrusor strips, when the peak amplitude of 80 mM K+-induced contraction in the absence of flavoxate was normalized as one.

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents

It was previously reported that the peak amplitude of nifedipine-sensitive voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in human detrusor was too small to estimate precisely (Kajioka et al., 2002). Thus, in the present experiments, Ba2+ (10 mM) was used as a charge carrier in the bath solution in order to enhance the amplitude of the inward currents for analysis and to isolate voltage-dependent inward Ca2+ currents by inhibiting other Ca2+-activated mechanisms (such as Ca2+-activated K+ currents and Ca2+-activated Cl− currents, etc.). The recording pipette was filled with a Cs+-TEA+ solution containing 5 mM EGTA.

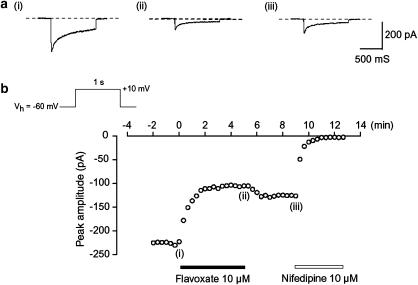

Application of a depolarizing step to +10 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV produced an inward Ba2+ current (Figure 3a(i)). This current increased slightly with time after establishing the whole-cell configuration, reaching a steady state approximately 4 min after rupture of the membrane patch (n=60). This peak value was then maintained at least for 15 min if test depolarization pulses (1 s duration) were applied at 20 s intervals (the peak amplitude of the voltage-dependent Ba2+ current at 15 min being 98±2% (n=10) of the value determined 4 min after establishment of a conventional whole-cell recordings). Consequently, all experiments were performed within this 15 min period.

Figure 3.

Effects of flavoxate and nifedipine on voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents in human detrusor. Whole-cell recording, pipette solution Cs+-TEA+ solution containing 5 mM EGTA and bath solution 10 mM Ba2+ containing 135 mM TEA+. (a) Original current traces before (control, (i)) and after application of 10 μM flavoxate (ii), as indicated in (b). (iii) Indicates a current trace just before the application of 10 μM nifedipine. (b) The time course of the effects of application of flavoxate and nifedipine on the peak amplitude of the voltage-dependent Ba2+ current evoked by repetitive depolarizing pulses to +10 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV. Time 0 indicates the time when 10 μM flavoxate was applied to the bath.

Effects of flavoxate on voltage-dependent Ba2+ inward currents

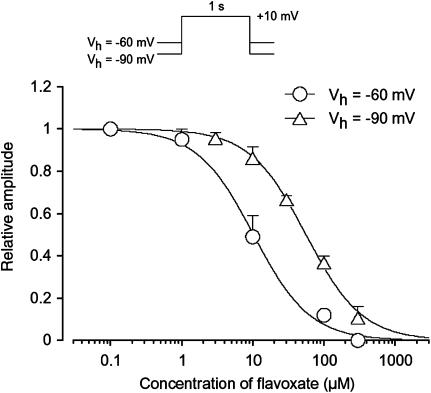

Figure 3b shows the time course of the effects of flavoxate (10 μM) on the Ba2+ inward current. Application of flavoxate (10 μM) gradually reduced the peak amplitude of the inward current and nearly halved it within a few min (0.49±0.1, n=5). Subsequent application of nifedipine (10 μM) completely suppressed the currents. Figure 4 shows the relationships between the relative peak amplitude of Ba2+ inward currents evoked by a depolarizing pulse to +10 mV from two different holding potentials (−60 and −90 mV) applied every 20 s and concentrations of flavoxate. Flavoxate inhibited the peak amplitude of the Ba2+ inward currents in a concentration-dependent manner (−60 mV, Ki=10 μM; −90 mV, Ki=56 μM).

Figure 4.

Concentration–response curves for flavoxate on voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents in human detrusor. Relationships between relative inhibition of the peak amplitude of Ba2+ current and the concentration of flavoxate at two holding potentials (−60 and −90 mV). The peak amplitude of the Ba2+ current elicited by a step pulse to +10 mV from the holding potential just before application of flavoxate was normalized as one. The curves were drawn by fitting the following equation using the least-squares method: Relative amplitude of voltage-dependent Ba2+ current=1/{1+(D/Ki) nH} where Ki, D and nH are the inhibitory dissociation constant, concentration of flavoxate (μM) and Hill's coefficient, respectively. The following values were used for the curve fitting: −60 mV, Ki=10 μM, nH=1.1; −90 mV, Ki=56 μM, nH=1.1. Each symbol indicates the mean of 5–15 observation with±s.d. shown by vertical lines. Some of the s.d. bars are less than the size of the symbol.

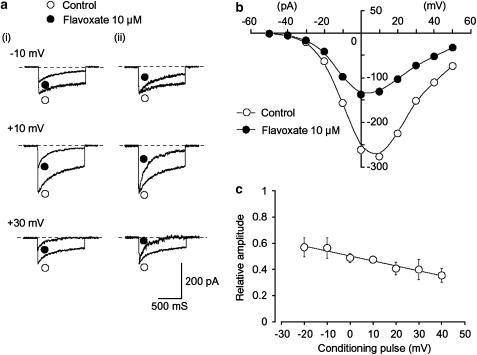

Voltage-dependent inhibitory effects of flavoxate on voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents

As shown in Figure 5a, flavoxate inhibited the peak amplitude of the Ba2+ currents evoked by depolarizing pulses (1 s duration) from a holding potential of −60 mV at levels more positive than −30 mV. Figure 5b shows the current–voltage relationships in the absence and presence of 10 μM flavoxate, and the inhibition showed a voltage-dependency (Figure 5c). This voltage-dependency was investigated before and after application of 30 μM flavoxate using the experimental protocol shown in Figure 6 (conditioning pulse duration, 8 s; holding membrane potential, −90 mV). In the absence of flavoxate (control), inactivation of the Ba2+ current occurred with depolarizing pulses positive to −50 mV. After application of 30 μM flavoxate (approximately 5 min later), the voltage-dependent inactivation curve in the same cells was shifted to the left (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Effects of flavoxate on voltage-dependent Ba2+ inward currents at a holding membrane potential of −60 mV in human detrusor. The pipette solution was Cs+-TEA+ solution containing 5 mM EGTA and the bath solution was 10 mM Ba2+ containing 135 mM TEA+. (a) (i) Original current traces before (control) and after application of 10 μM flavoxate at the indicated pulse potentials. (ii) Inward Ba2+ current from (i) scaled to match their peak amplitudes and superimposed. (b) Current–voltage relationships obtained in the absence (control) or presence of 10 μM flavoxate. The current amplitude was measured as the peak amplitude of the Ba2+ inward current in each condition. The lines were drawn by eye. (c) Relationship between the test potential and relative value of the Ba2+ inward currents inhibited by 10 μM flavoxate, expressed as a fraction of the peak amplitude of the Ba2+ inward current evoked by various amplitudes of depolarizing pulse in the absence of flavoxate. Each symbol indicates the mean of five observations with±s.d. shown by vertical lines. The line was drawn by eye.

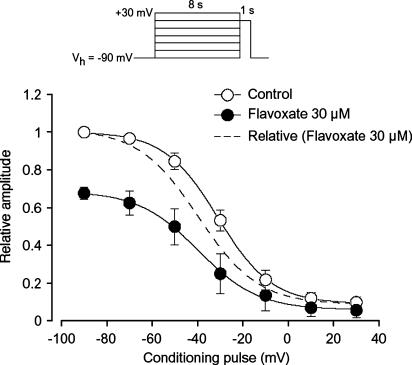

Figure 6.

Effects of flavoxate (30 μM) on the voltage-dependent inactivation of the Ba2+ inward currents in human detrusor. Whole-cell recording, pipette solution Cs+-TEA+ solution containing 5 mM EGTA and bath solution 10 mM Ba2+ containing 135 mM TEA+. The holding potential was −90 mV. Conditioning pulses of various amplitudes were applied (up to +30 mV, 8 s duration) before application of the test pulse (to +10 mV, 1 s duration). An interval of 20 ms was allowed between these two pulses to estimate possible contamination of the capacitive current. The peak amplitude of Ba2+ current evoked by each test pulse was measured before and after application of 30 μM flavoxate. The curves with the solid line; the peak amplitude of Ba2+ inward current in the absence and presence of flavoxate without application of any conditioning pulse was normalized as one. The curve with the broken line was normalised to the current at +10 mV upon stepping from −90 mV in 30 μM flavoxate. The lines were draw by fitting the data to the following equation in the least-squares method: I=(Imax–C)/{1+exp [(V–Vhalf)/k]}+C, where I, Imax, V, Vhalf, k and C are the relative amplitude of Ba2+ inward currents observed at various amplitude of the conditioning pulse (I) and observed with application of the conditioning pulse of −90 mV (Imax), amplitude of the conditioning pulse (V), and that where the amplitude of Ba2+ inward current was reduced to half (Vhalf), slope factor (k) and fraction of the noninactivating component of Ba2+ inward current (C). The curves in the absence or presence of flavoxate were drawn using the following values: (control), Imax=1, Vhalf=−31, k=12 and C=0.09 (flavoxate, 30 μM), Imax=0.68, Vhalf=−40, k=13 and C=0.06. Each symbol indicates the mean of 5–6 observations with±s.d. shown by vertical lines. Some of the s.d. bars are less than the size of the symbol.

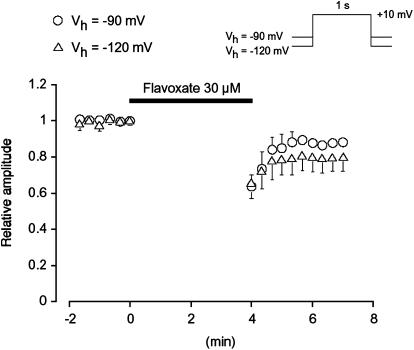

As shown in Figure 7, when a depolarizing pulse was applied from a holding potential of −90 mV after an interval of 4 min in the presence of 30 μM flavoxate, the peak amplitude of the Ba2+ inward current was smaller (0.64±0.07, n=5) than that observed before application of flavoxate; however, it was consistently larger than that recorded at 4 min with repetitive application of the depolarizing pulses (0.6±0.02, n=4). Similar reduction of the peak amplitude of the first depolarizing pulse after 4 min application of flavoxate was observed at the different holding potential (−120 mV, 0.66±0.09, n=5). On removal of flavoxate, the peak amplitude of the Ba2+ inward current gradually recovered, but did not recover to the control level.

Figure 7.

The effects of flavoxate on voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents. No pulses were applied for the initial 4 min after application of 30 μM flavoxate. Each symbol shows the size of the mean value of the peak amplitude of the voltage-dependent Ba2+ current evoked by the depolarizing pulses after this 4 min from two holding potentials (−90 mV, 0.64±0.07, n=5; −120 mV, 0.66±0.09, n=5). The peak amplitude of the voltage-dependent Ba2+ current just before application of flavoxate was normalized as one (control).

Immunohistochemical localization of CaV1.2 in human urinary bladder

As a search for the molecular correlate of CaV1.2 (α1C, i.e., L-type Ca2+ currents) characterized above, immunohistochemistry was performed to detect the expression of the CaV1.2 antigen (Figure 8a, b). As shown in Figure 8b, the CaV1.2 immunoreactivity is clearly visible in the membranes of the smooth muscle cells. In contrast, no specific immunoreactive signal was seen when primary antibody was preadsorbed with the immunizing CaV1.2 antigen (Figure 8c, d). Immunohistochemistry using nonimmune rabbit IgG instead of primary antibody also gave a negative result (data not shown).

Figure 8.

Fluorescent images of immunoreactivity for CaV1.2 in the human detrusor bundles. (a, b) CaV1.2 immunoactivity; clear membranous staining was observed at the tissues of the human urinary bladder smooth muscle layers. (c, d) Negative control: use of CaV1.2 antibody preadsorbed with the immunizing antigen never yields any colour reaction. Bar (white line in (d)) represents 200 μm.

Discussion

The present study provides the first direct electrophysiological evidence that flavoxate, a spasmolytic agent, inhibits L-type Ca2+ channels in human detrusor smooth muscle.

Inhibitory potency of flavoxate in urinary bladder

Previously, Malkowicz et al. (1987) concluded from tension measurements that flavoxate possessed no Ca2+ antagonist properties in rabbit detrusor. However, it has been reported that flavoxate causes a concentration-dependent relaxation of the tension elicited by muscarinic stimulation (IC50=35 μM) or 5 mM extracellular Ca2+ (IC50=83 μM) in rat detrusor (Kimura et al., 1996). In the present experiments, we found that flavoxate caused a concentration-dependent relaxation of human urinary bladder precontracted by K+ with much higher potency (IC50=2 μM). It is unknown at present whether nor not the different potency of flavoxate is due to the species difference. Furthermore, in human urinary bladder myocytes, we have been able to demonstrate directly that flavoxate suppressed voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents through L-type Ca2+ channels in a concentration-dependent manner by use of patch-clamp techniques. In rabbit detrusor myocytes, flavoxate also inhibited voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents with a similar potency (Ki=9 μM, unpublished observation, Teramoto). Thus, we suggest that flavoxate may possess a Ca2+ antagonistic action in human and rabbit detrusor myocytes and suppresses the contraction evoked by K+.

There is a small discrepancy regarding the potency of flavoxate between tension measurements (IC50=2 μM) and patch-clamp experiments (Ki=10 μM) in human urinary bladder. Since the K+-induced contraction probably results both from the membrane depolarization and release of ATP and ACh from the nerve terminals in the tissues, several mechanisms in the smooth muscles may be activated, including voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and receptor-operated Ca2+ entry pathways, etc. (reviewed by McFadzean & Gibson, 2002). It is conceivable that flavoxate may also modulate the other Ca2+ entry pathways, thus showing a stronger potency to inhibit the contractions than to suppress voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents in human detrusor.

Kinetic studies concerning the actions of flavoxate on voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents

The same amplitude of voltage-dependent Ba2+ currents was produced by application of depolarizing pulses from holding membrane potentials of −90 mV or more negative values, suggesting that all of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels at these potentials may be in the resting state. The ability of 30 μM flavoxate to suppress the peak amplitude of the Ba2+ currents evoked by a depolarizing pulse from two different holding potentials (−90 and −120 mV) were not significantly different, suggesting that at these negative holding potentials, flavoxate may inhibit the Ba2+ currents in a voltage-independent manner (resting state block). When the holding potential was elevated to −60 mV, voltage-dependent inhibition by flavoxate was observed and the concentration response curve was shifted to the left. The voltage-dependent inactivation curve was also shifted to the left after application of 30 μM flavoxate. These results suggest the voltage-dependent inhibitory actions of flavoxate occur at the inactivated state of the Ca2+ channels in human urinary bladder (voltage-dependent block). In the present experiments, the Krest value was estimated to be 56 μM from the concentration–response curve at a holding potential of −90 mV. When ΔVhalf value was obtained from the results using 8 s conditioning pulses, the estimated Kinact value was 8.6 μM (see Methods). Given this, we suggest that flavoxate may bind to the inactivated state with approximately 6.5 times higher affinity than to the resting state in human detrusor.

Pharmacological properties of flavoxate in lower urinary tract

The options for clinical treatment of urge frequency of micturition and overactive bladder (OAB) are currently behavioral techniques, pharmacological agents and surgical procedures. Owing to its availability, immediacy of results and convenience, pharmacotherapy (such as anticholinergic drugs, spasmolytic agents, estrogen) has advanced to alleviate the detrusor overactivity. Anticholinergic agents (such as oxybutynin, tolterodine and trospium chloride, etc.) are the most commonly used drugs (reviewed by Hegde et al., 2004). Binding studies have revealed that flavoxate also exhibits a weak but significant anticholinergic activity on muscarinic receptors (IC50=12 μM, Abbiati et al., 1988). However, the anticholinergic activity of flavoxate was much less potent than those of other anticholinergic agents (oxybutynin, IC50=5 nM; tolterodine, IC50=588 nM, Abbiati et al., 1988), and it is difficult to justify classification of flavoxate as an anticholinergic compound. Although efficacious as therapy for urge frequency of micturition, anticholinergic actions typically produced dry mouth, difficulty in visual accommodation, constipation and somnolence. In order to reduce these predictable side effects, much effort is currently being spent to find new approaches (such as α1 antagonists, β3 stimulants, K+ channel openers, etc.) for the treatment of urge frequency of micturition and OAB (reviewed by Andersson, 2004). In the present experiments, we have been able to demonstrate that flavoxate possesses a direct Ca2+ antagonistic action on voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ currents in human detrusor in addition to the actions as a modulator of the micturition centre in CNS (see Introduction). Thus, it seems plausible that the Ca2+ antagonistic actions of flavoxate are related to its spasmolytic effects on human urinary bladder. However, higher concentrations of flavoxate are required to cause the inhibitory effects on voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ currents in comparison to those in CNS. Andersson (1993) queried the usefulness of Ca2+ antagonists for the treatment of urinary incontinence and OAB due to their poor tissue selectivity. Further studies may be still necessary to work out the full details of binding site(s) for flavoxate.

In conclusion, we have been able to demonstrate that flavoxate caused a detrusor relaxation through inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channel in human urinary bladder.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Alison F. Brading (University, Department of Pharmacology, Oxford, U.K.) for her helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B)-(2) from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Noriyoshi Teramoto, Grant Number 16390067). We thank Mr Hiroshi Fujii for his excellent help with histological experiments.

Abbreviations

- CNS

central nervous system

- DHP

dihydropyridine

- DMSO

dimethyl sulphoxide

- flavoxate hydrochloride

piperidinoethyl-3-methylflavone-8-carboxylate hydrochloride

- OAB

overactive bladder

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- TEA+

tetraethylammonium

References

- ABBIATI G.A., CESERANI R., NARDI D., PIETRA C., TESTA R. Receptor binding studies of the flavone, REC 15/2053, and other bladder spasmolytics. Pharm. Res. 1988;5:430–433. doi: 10.1023/a:1015936417530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSSON K.E. Pharmacology of lower urinary tract smooth muscles and penile erectile tissues. Pharmacol. Rev. 1993;45:253–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSSON K.E. New pharmacologic targets for the treatment of the overactive bladder: an update. Urology. 2004;63:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAEUSLER G., LEITICH H., VAN TROTSENBURG M., KAIDER A., TEMPFER C.B. Drug therapy of urinary urge incontinence: a systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:1003–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEGDE S.S., MAMMEN M., JASPER J.R. Antimuscarinics for the treatment of overactive bladder: current options and emerging therapies. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2004;5:40–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAJIOKA S., NAKAYAMA S., MCMURRAY G., ABE K., BRADING A.F. Ca2+ channel properties in smooth muscle cells of the urinary bladder from pig and human. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;443:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01593-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KASEDA M., SATO A., SATO Y., TORIGATA Y. Effects of flavoxate hydrochloride (AK-123) on the vesical functions in rats. Clin. Physiol. 1975;5:540–547. [Google Scholar]

- KIMURA Y., SASAKI Y., HAMADA K., FUKUI H., UKAI Y., YOSHIKUNI Y., KIMURA K., SUGAYA K., NISHIZAWA O. Mechanisms of the suppression of the bladder activity by flavoxate. Int. J. Urol. 1996;3:218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1996.tb00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOHLER F.P., MORALES P.A. Cystometric evaluation of flavoxate hydrochloride in normal and neurogenic bladders. J. Urol. 1968;100:729–730. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)62610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALKOWICZ S.B., WEIN A.J., RUGGIERI M.R., LEVIN R.M. Comparison of calcium antagonist properties of antispasmotic agents. J. Urol. 1987;138:667–670. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCFADZEAN I., GIBSON A. The developing relationship between receptor-operated and store-operated calcium channels in smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKA M., KIMURA Y., ITOH Y., SASAKI Y., TANIGUCHI N., UKAI Y., YOSHIKUNI Y., KIMURA K. Brain pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins are involved in the flavoxate hydrochloride-induced suppression of the micturition reflex in rats. Brain Res. 1996;727:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PÉRÉON Y., DETTBARN C., LU Y., WESTLUND K.N., ZHANG J.T., PALADE P. Dihydropyridine receptor isoform expression in adult rat skeletal muscle. Pflügers Arch. 1998;436:309–314. doi: 10.1007/s004240050637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERAMOTO N., BRADING A.F. Activation by levcromakalim and metabolic inhibition of glibenclamide-sensitive K channels in smooth muscle cells of pig proximal urethra. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:635–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERAMOTO N., BRADING A.F., ITO Y. Multiple effects of mefenamic acid on K+ currents in smooth muscle cells from pig urethra. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;140:1341–1350. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TERAMOTO N., YUNOKI T., IKAWA S., TAKANO N., TANAKA K., SEKI N., NAITO S., ITO Y. The involvement of L-type Ca2+ channels in the relaxant effects of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel opener ZD6169 on pig urethral smooth muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1505–1515. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UCKERT S., STIEF C.G., ODENTHAL K.P., TRUSS M.C., LIETZ B., JONAS U. Responses of isolated normal human detrusor muscle to various spasmolytic drugs commonly used in the treatment of the overactive bladder. Arzneimittelforschung. 2000;50:456–460. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UEHARA A., HUME J.R. Interactions of organic calcium channel antagonists with calcium channels in single frog atrial cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 1985;85:621–647. doi: 10.1085/jgp.85.5.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOSHIMURA N., SASA A., YOSHIDA O., TAKAORI S. Inhibitory effects of Hachimijiogan on micturition reflex via locus coeruleus. Folia Pharmacol. Jpn. 1992;99:161–166. doi: 10.1254/fpj.99.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]