Abstract

In this study, we utilised a number of adenoviral constructs in order to examine the role of intermediates of the NF-κB pathway in the regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) induction in rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMCs).

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated a significant increase in iNOS induction and NF-κB DNA binding. These parameters were substantially reduced by overexpression of a wild-type Iκ-Bα adenoviral construct (Ad.Iκ-Bα), confirming a role for NF-κB in iNOS induction.

Infection with a dominant-negative IKKα adenoviral construct (Ad.IKKα+/−) did not significantly affect iNOS induction, NF-κB DNA binding or Iκ-Bα loss. Infection of RASMCs with adenovirus encoding a dominant-negative IKKβ (Ad.IKKβ+/−) essentially abolished iNOS induction and activation of the NF-κB pathway.

Pretreatment of RASMCs with a novel specific inhibitor of IKKβ, SC-514, significantly reduced iNOS induction, NF-κB DNA binding and I-κBα loss in a concentration-dependent manner.

In both RASMCs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), infection with Ad.IKKβ+/− also inhibited COX-2 expression in response to LPS. However, Ad.IKKα+/− was again without effect.

These data suggest that IKKβ plays a predominant, selective role in the regulation of NF-κB-dependent induction of iNOS in RASMCs.

Keywords: Aortic smooth muscle cells, inducible nitric oxide synthase, inhibitory kappa B kinase, lipopolysaccharide, nuclear factor kappa B

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the active cell wall component of Gram-negative bacteria that leads to systemic shock (Mayeux, 1997; Heumann et al., 1998), mediates its actions through a family of receptors known as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (O'Neill, 2000; Swantek et al., 2000). TLR-4 is favoured as the LPS receptor, although there is evidence that TLR-2 is responsive to purified isolates of LPS (Poltorak et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1999; Akira, 2000; O'Neill, 2000). The TLRs in mediating their intracellular effects utilise various IL-1 (interleukin-1) signalling pathway proteins such as MyD88, IL-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK), tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-6, TRAF-2, and transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase (TAK1) (Swantek et al., 2000; Takeuchi & Akira, 2001; O'Neill, 2002).

A key signalling pathway involved in the actions of TLRs is the Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathway (Zhang & Ghosh, 2000; Faure et al., 2001). Binding sites for the NF-κB family of transcription factors have been identified within the promoter of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and other genes known to be regulated by LPS in several cell types (Muller et al., 1993; Yamamoto et al., 1995; D'Acquisto et al., 1997; Rao, 2000) including rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMCs) (De Martin et al., 2000). A substantial body of evidence supports a role for a family of kinases known as the inhibitory kappa B kinases (IKKs) in the regulation of NF-κB. These kinases are thought to regulate the phosphorylation status of the inhibitory protein, inhibitory kappa B(IκB)-α. Phosphorylation of Iκ-Bα promotes its dissociation from NF-κB and its degradation. NF-κB in turn is free then to translocate to the nucleus (Rothwarf & Karin, 1999; Karin & Ben-Neriah, 2000). Additionally, the IKKs are regulated by a series of additional MAP3 kinases such as NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) (Regnier et al., 1997; Woronicz et al., 1997), MEKK3 (Zhao & Lee, 1999) and others depending upon the receptor activated. Recent evidence also suggests different roles for IKKβ and IKKα in the regulation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. Several in vitro studies and others using deletion mice suggest that IKKβ is essential for the liberation of NF-κB and cytokine production (O'Connell et al., 1998; Li et al., 1999a, 1999b; Schwabe et al., 2001). However, IKKα has been implicated in the regulation of other events including; the phosphorylation of p65 NF-κB and histone H3 or other histone kinases (Senftleben et al., 2001; Anest et al., 2003; Yamamoto et al., 2003) and regulation of morphogenesis and tissue formation (Hu et al., 1999; Takeda et al., 1999; Senftleben et al., 2001; Bell et al., 2003). Thus, while IKKα is also able to regulate NF-κB-dependent gene transcription this effect is indirect.

While NF-κB has been implicated in the regulation of a number of genes in vascular smooth muscle cells (Collins & Cybulsky, 2001), the respective roles of IKKα and IKKβ have not been determined. Previous studies from our laboratory using transient transfection procedures have implicated both kinases in the regulation of NF-κB gene transcription (Torrie et al., 2001) however, effects upon protein expression have not been determined. Thus, we utilised dominant-negative adenoviral versions of IKKα and IKKβ, Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/−, respectively, to assess effects upon iNOS and COX-2 in relation to those effects upon NF-κB activation.

Methods

Materials

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and foetal calf serum foetal calf serum (FCS) were purchased from Invitrogen (Paisley, Scotland). LPS and DAPI were from Sigma Aldrich (Dorset, U.K.). Antibodies against iNOS, Iκ-Bα, and IKKα and -β were obtained from Santa Cruz (Insight Biotechnology, Middlesex, U.K.). COX-2 antibody was purchased from Alexis corporation (Merk Biosciences, Nottingham, U.K.). FITC-, Rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody were from Stratech scientific (Soham, U.K.). Nitrocellulose membrane and the ECL detection system were from Amersham Bioscience (Buckinghamshire, U.K.). [γ-32P]-ATP (3000 Ci mmol−1) was from Perkin Elmer LAS. Ltd (Bucks, U.K.). 32P-labelled double-stranded NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide (5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′) was purchased from Promega (Southampton, U.K.). The dominant-negative IKK-α and -β plasmids and that for dominant-negative NIK were kind gifts from Dr D. Goeddel (Tularik Inc., CA, U.S.A.). Cryopreserved pooled human umbilical vein endothelial cells(HUVECs), and endothelial cell growth medium-2 (EGM-2) were purchased from Cambrex Bioscience (Berkshire, U.K.). Methanol was obtained from Bamford Laboratories (Rochdale, U.K.) and BSA from Boehringer Manheim (East Sussex, U.K.). SC-514 inhibitor and Mowiol were purchased from Calbiochem (Merck Biosciences, Nottingham, U.K.).

Cell culture

Smooth muscle cells were isolated from the thoracic aortae of 180–200 g male Sprague–Dawley rats by digestion with collagenase and elastase as previously described (Paul et al., 1997a; Oitzinger et al., 2001). RASMCs were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FCS and used as previously outlined (Plevin et al., 1996; Paul et al., 1997a). HUVECs were grown in endothelial cell basal medium supplemented with EGM-2 singlequots (2% foetal bovine serum, 0.2 ml hydrocortisone, 2 ml hFGF-B, 0.5 ml VEGF, 0.5 ml R3-insulin like growth factor-1, 0.5 ml ascorbic acid, 0.5 ml hEGF, 0.5 ml GA 1000, 0.5 ml heparin). Cells were incubated at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2 and quiesced in serum-free medium 48 h prior to stimulation with LPS (100 μg ml−1) in serum-free medium.

Purification of adenovirus

Recombinant replication-deficient adenoviral vectors encoding a kinase-deficient IKKα (Ad.IKKα+/−) or IKKβ (Ad.IKKβ+/−) gene, which act in a dominant-negative manner, or encoding wild-type porcine Iκ-Bα gene (Ad.Iκ-Bα) were used. These constructs were previously described by Regnier et al. (1997) and Oitzinger et al. (2001), respectively. The virus was propagated in 293 human embryonic kidney cells, then purified by ultracentrifugation in a caesium chloride gradient. The titre of the viral stock was determined by the end point dilution method (Nicklin & Baker, 1999). RASMCs when approx. 70% confluent were incubated with adenovirus in a range between 10 and 300 plaque forming units per cell (pfu/cell) for 16 h in normal growth medium. The cells were stimulated 40 h postinfection and quiesced in serum-free medium for 16 h prior to stimulation.

Western blot analysis

As previously described (Paul et al., 1997a), proteins (10 μg per lane) were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose. To reduce nonspecific binding the membranes were incubated for 2 h in 2% BSA (w : v) diluted in NATT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% (v : v) Tween-20) and then incubated overnight with 50 ng ml−1 primary antibody diluted in 0.2% BSA (w : v) in NATT buffer. Blots were washed with NATT buffer for 2 h and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (20 ng ml−1 in 0.2% BSA (w : v) diluted in NATT buffer) for 2 h. After a further 2 h wash, the blots were subjected to ECL reagent and exposed to Kodak X-ray film. All the antibodies were titred to give optimum detection conditions.

Immunofluorescence

The cells were grown to confluency (on glass coverslips) in six-well plates. The coverslips were washed twice with PBS, prior to fixation with cold methanol for 10 min. The coverslips were incubated with 1% BSA (w : v) diluted in PBS for 30 min to prevent nonspecific binding and incubated with primary antibodies (500 ng ml−1) for 1 h. They were further washed three times in PBS and incubated with FITC- and/or rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody with DAPI (100 ng ml−1) for 45 min. The coverslips were then washed three times in PBS and mounted onto slides embedded in Mowiol for visualisation by EPI fluorescence light microscopy (Eclipse E600 fluorescent microscopy, Nikon, Kingston upon Thames, U.K.).

Assay of NF-κB activity: electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Preparation of nuclear extracts

RASMCs were grown on 10 cm2 dishes, exposed to vehicle or LPS, and reactions terminated by washing cells twice with ice-cold PBS. Cells were then removed by scraping and transferred to Eppendorf tubes. Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described (Schreiber et al., 1989) and the protein content of the recovered samples then determined by means of Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976).

DNA-binding reaction

Nuclear extracts (5 μg) were incubated in binding buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 4% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 50 mM NaCl, 50 μg ml−1 poly(dI-dC).poly(dI-dC) for 15 min prior to addition of 1 μl (50 000 c.p.m.) of 32P-labelled double-stranded NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide (5′-AGT TGA GGG GAC TTT CCC AGG C-3′) for 20–30 min. Following incubation, 1 μl of gel loading buffer (10 × ; 250 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.2% (w/v) bromophenol blue, 40% (v/v) glycerol) was added to samples and protein-DNA complexes resolved by nondenaturing electrophoresis on 5% (w/v) acrylamide slab gels. Gels were initially pre-run in (0.5 ×) Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (TBE) for 30 min at 100 V and subsequent to loading of samples maintained at 100 V for 45–60 min. Gels were dried and NF-κB-probe complexes visualised by autoradiography.

Measurement of nitrate/nitrite production

Nitrate/nitrite concentration in the cell culture medium was estimated spectrophotometrically using Greiss reagent following a 24 h stimulation with LPS at 100 μg ml−1, as previously described in Paul et al. (1997a, 1997b).

Analysis of data

Densitometry measurement was performed by using Scion Image beta 3b program. Data were expressed as the mean±s.e.m. and analysed with a two-tailed Student's t-test at a P<0.05 level of significance.

Results

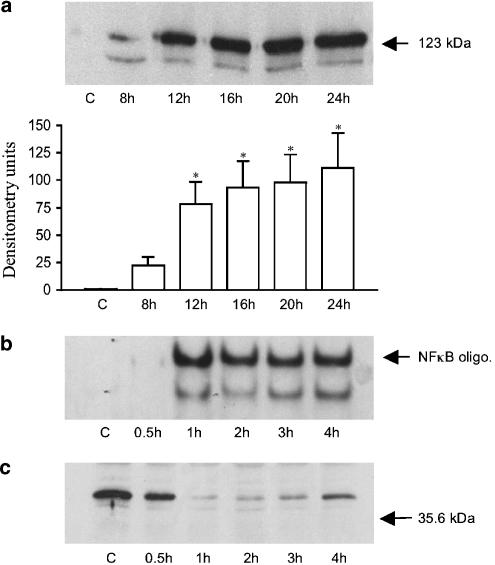

Figure 1 shows the kinetics of LPS-stimulated iNOS induction and NF-κB activation in response to LPS. As expected, LPS stimulated a maximal increase in iNOS induction at approximately 12–24 h as previously described in (Paul et al., 1997b) (panel a). This was associated with a strong increase in LPS stimulated NF-κB DNA binding, which was maximal by 60 min and lasted for at least 4 h, the longest time point assayed (panel b). LPS also stimulated a transient loss in cellular Iκ-Bα expression (panel c) and an increase in IKK activity (not shown) as characterised previously (Torrie et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

LPS-stimulated iNOS induction, NF-κB DNA binding and Iκ-Bα loss in RASMCs. RASMCs rendered quiescent were stimulated with 100 μg ml−1 LPS for the times indicated and iNOS (a), NF-κB DNA binding (b) and Iκ-Bα levels (c) assayed as outlined in the Methods section. Each gel is representative of at least four experiments. In (a), levels were quantified by densitometry. Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. (densitometry units) from at least 4 experiments (*P<0.05 vs control cells).

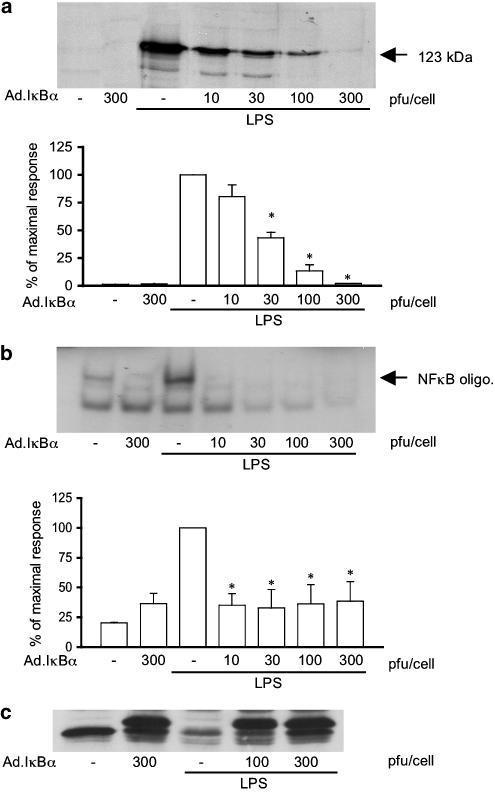

Initially the effect of Ad.Iκ-Bα was assessed to confirm a role for the NF-κB signalling pathway in the regulation of iNOS induction in response to LPS (Figure 2). Infection of RASMCs with Ad.Iκ-Bα reduced iNOS induction in a concentration-dependent manner with maximum inhibition over the range of 100–300 pfu cell−1 (panel a). Over the same concentration range, Ad.Iκ-Bα also abolished LPS-stimulated NF-κB DNA binding (Figure 2, panel b). This is consistent with a role for NF-κB in the regulation of iNOS. Panel c, in Figure 2, is a Western blot for Iκ-Bα. The overexpression of the adenoviral Iκ-Bα provides an excess of Iκ-Bα that prevents the translocation of NF-κB. This excess is clear in the adenovirally-infected lysates from the control and LPS-stimulated cells. The adenoviral wild-type porcine Iκ-Bα has lower mobility on the gel than the endogenous rat Iκ-Bα and therefore runs at a slightly higher position.

Figure 2.

Effect of Ad.Iκ-Bα upon LPS-stimulated iNOS induction and NF-κB DNA binding in RASMCs. Cells were infected with Ad.Iκ-Bα (10–300 pfu cell−1) for 48 h and stimulated with LPS (100 μg ml−1) for 24 h for iNOS expression (a) and 1 h for NF-κB-DNA binding (b) or Iκ-Bα degradation (c). Each blot represents at least 4 experiments. Gels were quantified by densitometry. Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from at least 4 experiments (*P<0.05 vs LPS-infected cells).

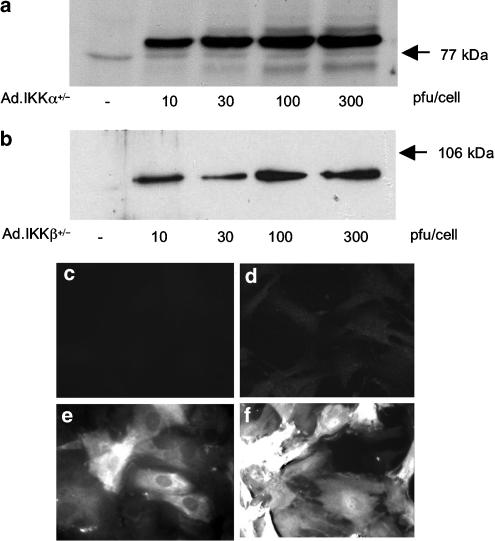

Adenoviruses encoding Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/− were tested for infection efficiency (Figure 3). Western blot analysis showed that all viruses infected RASMCs in a concentration-dependent manner. For both Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/−, maximal expression was achieved between 100 and 300 pfu cell−1 (Figure 3, panels a and b). At a concentration of 300 pfu cell−1, an immunofluorescence study utilising specific antibodies showed that, both Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/− (panels e and f, respectively) infected 90–100% of cells when compared to untreated cells (panels c and d) although cells were infected to different levels.

Figure 3.

Cellular expression of Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/− in RASMCs. RASMCs were infected with increasing concentrations of Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/− and assessed for protein expression as outlined in the Methods section (a and b, respectively). Cellular expression of Ad.IKKα+/− (e) and Ad.IKKβ+/− (f) at 300 pfu cell−1 was assessed by indirect immuno-fluorescence and compared to uninfected cells (c and d, respectively). Each panel is a representative example from at least four experiments.

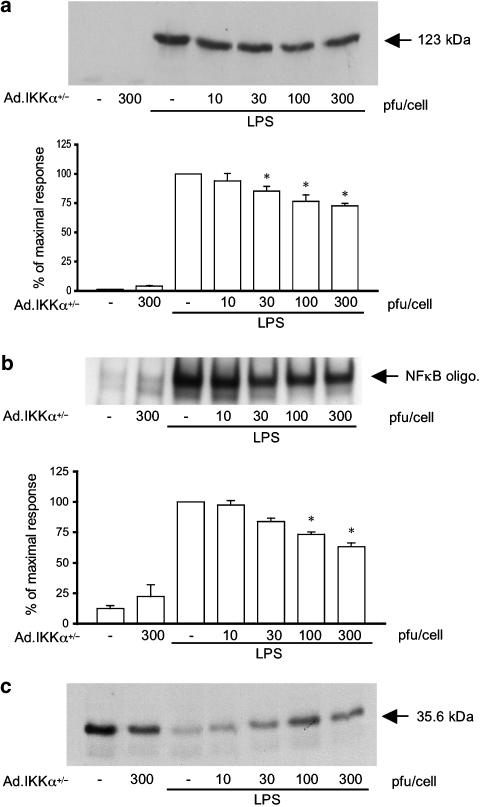

Figure 4 shows the effect of Ad.IKKα+/− upon LPS-stimulated iNOS induction and activation of the NF-κB pathway. Despite consistently high levels of infection, the mutant variant of IKKα had a minor, although statistically significant, effect upon iNOS induction reducing maximum levels by 30% at 300 pfu cell−1 (Figure 4, panel a). Similarly, NF-κB DNA binding was affected in the same manner by Ad.IKKα+/− infection with minor decreases observed at higher concentrations of adenovirus (Figure 4, panel b). Some reversal of Iκ-Bα loss was also observed at 300 pfu cell−1, however, this effect was difficult to quantify since at high concentration the virus alone was able to initiate a minor degradation in Iκ-Bα.

Figure 4.

The effect of Ad.IKKα+/− upon LPS-stimulated iNOS induction, NF-κB-DNA binding and Iκ-Bα loss in RASMCs. Cells were infected with increasing amounts of Ad.IKKα+/− for 48 h and then stimulated with LPS (100 μg ml−1) for further time periods as outlined. Extracts were assayed for iNOS expression (a), NF-κB DNA binding (b), and Iκ-Bα loss (c). Each blot represents at least 4 experiments. Gels were quantified by densitometry. Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from at least 4 experiments (*P<0.05 vs LPS-treated cells).

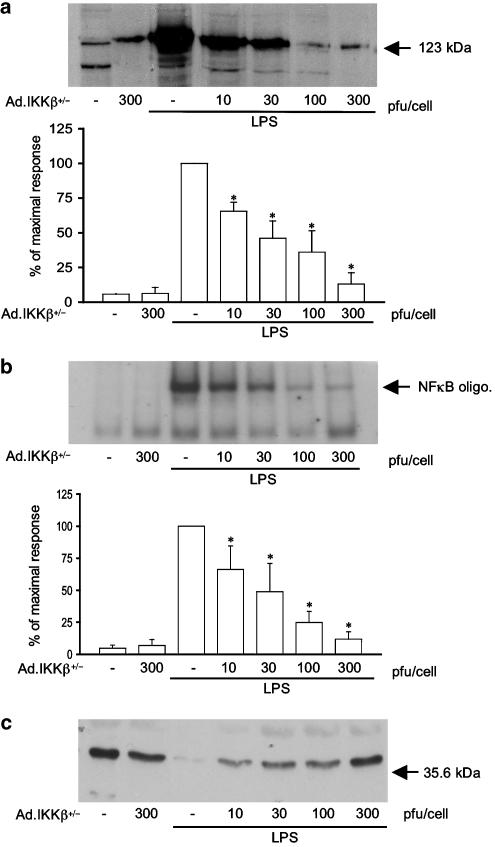

In contrast to the minor effect of Ad.IKKα+/−, Ad.IKKβ+/− substantially inhibited LPS stimulated iNOS expression and associated activation of the NF-κB pathway (Figure 5). Indeed, as with Iκ-Bα, this viral construct inhibited iNOS induction in response to LPS in a concentration-dependent manner. At concentrations as little as 30 pfu cell−1, Ad.IKKβ+/− reduced iNOS induction by approximately 50% with complete abolition being observed by 300 pfu cell−1 (Figure 5, panel a). A similar, concentration-dependent effect was observed at the level of NF-κB DNA binding and Iκ-Bα loss (Figure 5, panels b and c, respectively), suggesting a critical role for IKKβ in the induction of iNOS. As a measure of iNOS activity, LPS-stimulated nitrate and nitrite production was also measured, as described in Methods. A 24-h stimulation with LPS (100 μg ml−1) caused an elevation of nitrate/nitrite concentration from a basal level of 0.051±0.000 to 0.182±0.003 absorbance units (A540, n=3), equivalent to a concentration of approx. 300 μM nitrate/nitrite. A treatment with Ad.IKKβ+/− at 300 pfu cell−1 had no effect on basal levels (0.054±0.000, n=3) but caused a total inhibition of LPS-stimulated nitrate/nitrite production (0.056±0.000, n=3).

Figure 5.

The effect of Ad.IKKβ+/− upon LPS-stimulated iNOS induction, NF-κB-DNA binding and Iκ-Bα loss in RASMCs. Cells were infected with increasing doses of Ad.IKKβ+/− (pfu cell−1) for 48 h and then stimulated with LPS (100 μg ml−1) for further time periods as outlined. Extracts were assayed for iNOS (a), NF-κB-DNA binding (b) and Iκ-Bα levels (c). Each blot represents at least four experiments. Gels were quantified by densitometry. Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from at least four experiments (*P<0.05 vs LPS-treated cells).

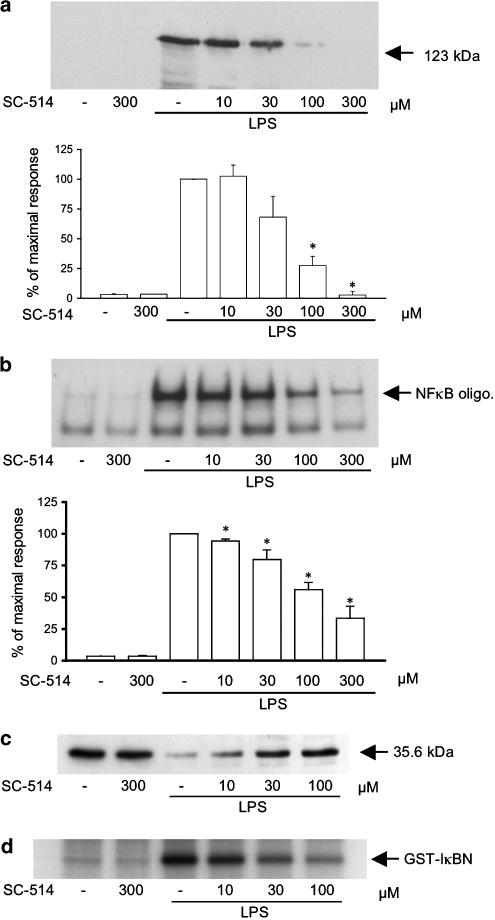

In order to confirm the selective role of IKKβ in regulating iNOS expression, the novel IKKβ inhibitor, SC-514 (Kishore et al., 2003), was utilised (Figure 6). Pre-treatment of cells with this drug strongly inhibited LPS-stimulated increased iNOS expression, with full inhibition observed between 100 and 300 μM (Figure 6, panel a). NF-κB DNA binding was also inhibited at higher concentrations of the drug (Figure 6, panel b) as was LPS-simulated Iκ-Bα loss (Figure 6, panel c) and IKK activity (Figure 6, panel d).

Figure 6.

The effect of the IKKβ selective inhibitor SC-514 upon LPS-stimulated iNOS induction, NF-κB-DNA binding, Iκ-Bα loss and IKK activity in RASMCs. RASMCs were pre-treated with increasing amounts of inhibitor (10–300 μM) and stimulated with LPS (100 μg ml−1) for the times indicated. Cellular extracts were assayed for iNOS expression (a), NF-κB DNA binding (b), Iκ-Bα loss (c) and IKK activity (d). Each blot is representative of at least four others. Gels were quantified by densitometry. Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from at least four experiments (*P<0.05 vs LPS-stimulated cells).

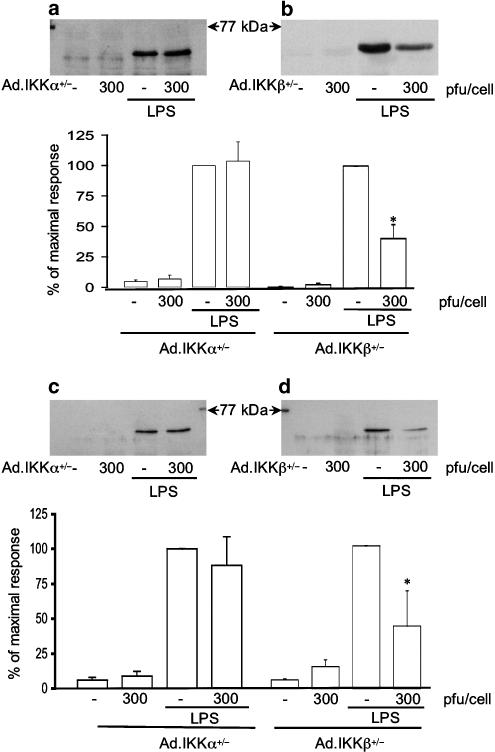

In order to address the possibility that the actions of IKKα are gene or cell-type specific, expression of COX-2 in both RASMCs and HUVECs was examined. Infection of RASMCs with Ad.IKKβ+/− significantly reduced COX-2 expression in response to LPS by approximately 60% (Figure 7, panel b), however, once again infection of cells with Ad.IKKα+/− virus was without effect (Figure 7, panel a). Further experiments performed in HUVECs demonstrated the same phenomenon, Ad.IKKα+/− was without effect whereas Ad.IKKβ+/− inhibited COX-2 expression by a similar amount (Figure 7, panels c and d).

Figure 7.

The effect of Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/− upon LPS-stimulated induction of COX-2 expression in RASMCs and HUVECS. RASMCs (a and b) or HUVECs (c and d) were infected with Ad.IKKα+/− (a and c) and Ad.IKKβ+/− (b and d) for 48 h then stimulated with LPS (100 μg ml−1) for a further 24 h. Cellular extracts were assayed for COX-2 expression as outlined in the Methods section. Each blot is representative of at least four others. Gels were quantified by densitometry. Each value represents the mean±s.e.m. from at least four experiments (*P<0.05 vs LPS-stimulated cells).

Discussion

In this study, we sought to define for the first time relative roles for IKK isoforms in the regulation of NF-κB-dependent gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells, with a view to seeking novel targets for drugs directed against septic shock and other diseases such as atherosclerosis. Owing to the relative lack of selective inhibitors of intermediates of the NF-κB pathway, in particular the IKKs, we utilised adenoviral approaches utilising dominant-negative constructs of the two main active isoforms, IKKα and -β.

Preliminary experiments confirmed the idea of an NF-κB-dependent pathway in the regulation of iNOS induction. Infection with Ad.Iκ-Bα effectively provides high levels of cellular IκBα, which despite agonist-mediated phosphorylation, is not adequately degraded through the proteosomal system and therefore is sufficient to prevent NF-κB translocation to the nucleus. This construct has previously been utilised to abolish NF-κB-dependent IRF-1 expression in HUVECs (Liu et al., 2001) suggesting it is an effective tool to dissect NF-κB signalling. In this study, Ad.Iκ-Bα appeared to be a more effective inhibitor of NF-κB DNA binding than of iNOS induction at low levels of pfu/cell (Figure 2). Although there is some inhibition of iNOS induction at the lowest concentration of Ad.Iκ-Bα used the inhibition of NF-κB DNA binding is greater. Therefore, there appears to be some variation between the concentrations of Ad.Iκ-Bα effective for inhibition of the short-term response and that required for inhibition of the longer term response.

The results obtained using Ad.Iκ-Bα confirms the results obtained in previous studies using pharmacological tools including PDTC (MacKenzie et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2004), D609 (Luo et al., 2003), hydrogen peroxide (Torrie et al., 2001), and hypertonic agents (Pingle et al., 2003). However, a number of these agents have questionable specificity (MacKenzie et al., 2003) thus, our work with Ad.Iκ-Bα is an important confirmatory study in this regard.

Our main findings, however, show for the first time that IKKβ rather than IKKα plays a major regulatory role in iNOS induction in vascular smooth muscle cells. Overexpression of Ad.IKKβ+/− effectively inhibited induction of this protein and significantly reduced intermediate events involved in NF-κB activation including cellular Iκ-Bα loss and increased NF-κB DNA binding. Inhibition of IKK activity has previously been demonstrated for this construct in RASMCs and abolished IKKβ activity in this system (MacKenzie et al., 2003). Other groups have utilised either Ad.Iκ-Bα or, more recently, Ad.IKKβ+/− to assess the role of the NF-κB pathways in proinflammatory mediator production in epithelial cells with similar results (Jobin et al., 1998).

In contrast we found little or no effect of Ad.IKKα+/− upon iNOS induction and associated parameters. These results contrast with our previous studies utilising RASMCs in a transient transfection system. In this study, both Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.IKKβ+/− were equally effectively in reducing LPS-induced NF-κB reporter activity (Torrie et al., 2001). One possible reason for this is a mass action effect whereby overexpression of IKKα+/− also inhibits IKKβ activity. This is particularly likely as the IKKs are known to exist as both homo- and heterodimers (Mercurio et al., 1997; Li et al., 1999c). Thus, a degree of overlap may occur and would explain why Ad.IKKα+/− has some limited effect upon iNOS induction and NF-κB activation. Few studies have utilised Ad.IKKα+/−, however the Rho-dependent IKKα pathway is implicated in the regulation of iNOS induction in neuronal-derived cell lines (Rattan et al., 2003). Nevertheless, a very recent study has found a similar pattern of inhibition in cells cultured from atherosclerotic plaques (Monaco et al., 2004); Ad.IKKβ+/− inhibited expression of a number of proinflammatory cytokines while Ad.IKKα+/− and Ad.NIK+/− were without effect. Interestingly, we also found that whilst NIK+/− was effective in transient transfection experiments (Torrie et al., 2001) no inhibition of iNOS induction was observed using the equivalent Ad.NIK+/− adenovirus (results not shown). This exemplifies the potential artifactual results of using transient transfection where large accumulation of expressed protein occurs in relatively small numbers of cells. Indeed, two recent studies have found that transient transfection of IKKα+/− and NIK+/− but not IKKβ+/− was able to reduce IL-1β- or LPS-induced COX-2 expression in canine tracheal smooth muscle cells (Yang et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2003). Since IKKβ is now regarded as essential for NF-κB activation (Karin, 1999; Li et al., 1999c) and NF-κB is recognised to regulate COX-2 expression, these results could be explained in this way. Whilst NIK could function upstream in the cascade it is possible that Ad.NIK+/− is competing with other endogenous MAP3 kinases such as MEKK3, known to be upstream in the IKK signalling pathway (Zhao & Lee, 1999).

Using a novel putative inhibitor of IKKβ we confirmed the essential role for IKKβ in the regulation of iNOS induction. SC-514 has been shown to be effective in blocking NF-κB dependent-gene induction in IL-1β-stimulated synovial fibroblasts through a selective inhibitory action upon IKKβ (Kishore et al., 2003). We found the inhibitor to be slightly less potent than described in this system as judged by effects upon IKKβ kinase activity where, in vitro, complete inhibition was not observed. However, it is likely that this may be accounted for by the difference in assay methods used to assess inhibition, or possibly the potential for SC-514 to have effects in addition to inhibition of IKKβ.

We observed that the selective effects of IKKβ inhibition are extended to other genes such as COX-2 and other cell types of the vasculature. Current evidence restricts a role for IKKα to induction of NF-κB2 processing (Senftleben et al., 2001), p65 phosphorylation and trans-activation (Madrid et al., 2001), histone phosphorylation and acetylation (Yamamoto et al., 2003), and Cyclin D1 activation (Cao et al., 2001). In preliminary studies, it has been shown that the IKKα dominant-negative virus is effective, infection results in the negative regulation of the expression of PAR-2 in HUVECs (results not shown). Thus, its role in gene regulation may be far more discrete and may involve a distinct subset of genes not as yet identified. Affymetrix gene technology is currently being used in the laboratory to identify these genes.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by a Research fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education, Science and Sports. Support is also acknowledged from the British Heart Foundation to Robin Plevin and Andrew Paul.

Abbreviations

- Ad.Iκ-Bα

Iκ-Bα wild-type adenoviral construct

- Ad.IKKα+/−

IKKα dominant-negative adenoviral construct

- Ad.IKKβ+/−

IKKβ dominant-negative adenoviral construct

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EBM

endothelial cell basal medium

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- FCS

foetal calf serum

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- IKK

inhibitory kappa B kinase

- IL-1

interleukin-1

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IRAK

IL-1 receptor-associated kinase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAP kinase

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEKK3

MAP/ERK kinase kinase-3

- NIK

NF-κB-inducing kinase

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- pfu

plaque-forming units

- RASMCs

rat aortic smooth muscle cells

- TAK1

transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TRAF

TNF receptor-associated factor

References

- AKIRA S. Toll-like receptors: lessons from knockout mice. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2000;28:551–556. doi: 10.1042/bst0280551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANEST V., HANSON J.L., COGSWELL P.C., STEINBRECHER K.A., STRAHL B.D., BALDWIN A.S. A nucleosomal function for IkappaB kinase-alpha in NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. Nature. 2003;423:659–663. doi: 10.1038/nature01648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELL S., DEGITZ K., QUIRLING M., JILG N., PAGE S., BRAND K. Involvement of NF-kappaB signalling in skin physiology and disease. Cell Signal. 2003;15:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRADFORD M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAO Y., BONIZZI G., SEAGROVES T.N., GRETEN F.R., JOHNSON R., SCHMIDT E.V., KARIN M. IKKalpha provides an essential link between RANK signaling and cyclin D1 expression during mammary gland development. Cell. 2001;107:763–775. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS T., CYBULSKY M.I. NF-kappaB: pivotal mediator or innocent bystander in atherogenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:255–264. doi: 10.1172/JCI10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'ACQUISTO F., IUVONE T., ROMBOLA L., SAUTEBIN L., DI ROSA M., CARNUCCIO R. Involvement of NF-kappaB in the regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 protein expression in LPS-stimulated J774 macrophages. FEBS Lett. 1997;418:175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE MARTIN R., HOETH M., HOFER-WARBINEK R., SCHMID J.A. The transcription factor NF-kappa B and the regulation of vascular cell function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000;20:E83–E88. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.e83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAURE E., THOMAS L., XU H., MEDVEDEV A., EQUILS O., ARDITI M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma induce Toll-like receptor 2 and Toll-like receptor 4 expression in human endothelial cells: role of NF-kappa B activation. J. Immunol. 2001;166:2018–2024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEUMANN D., GLAUSER M.P., CALANDRA T. Molecular basis of host–pathogen interaction in septic shock. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1998;1:49–55. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HU Y., BAUD V., DELHASE M., ZHANG P., DEERINCK T., ELLISMAN M., JOHNSON R., KARIN M. Abnormal morphogenesis but intact IKK activation in mice lacking the IKKalpha subunit of IkappaB kinase. Science. 1999;284:316–320. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOBIN C., PANJA A., HELLERBRAND C., IIMURO Y., DIDONATO J., BRENNER D.A., SARTOR R.B. Inhibition of proinflammatory molecule production by adenovirus-mediated expression of a nuclear factor kappaB super-repressor in human intestinal epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 1998;160:410–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARIN M. How NF-kappaB is activated: the role of the IkappaB kinase (IKK) complex. Oncogene. 1999;18:6867–6874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARIN M., BEN-NERIAH Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KISHORE N., SOMMERS C., MATHIALAGAN S., GUZOVA J., YAO M., HAUSER S., HUYNH K., BONAR S., MIELKE C., ALBEE L., WEIER R., GRANETO M., HANAU C., PERRY T., TRIPP C.S. A selective IKK-2 inhibitor blocks NF-kappa B-dependent gene expression in interleukin-1 beta-stimulated synovial fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:32861–32871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI Q., VAN ANTWERP D., MERCURIO F., LEE K.F., VERMA I.M. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IkappaB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999a;284:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI X.H., MURPHY K.M., PALKA K.T., SURABHI R.M., GAYNOR R.B. The human T-cell leukemia virus type-1 Tax protein regulates the activity of the IkappaB kinase complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1999b;274:34417–34424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI Z.W., CHU W., HU Y., DELHASE M., DEERINCK T., ELLISMAN M., JOHNSON R., KARIN M. The IKKbeta subunit of IkappaB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor kappaB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 1999c;189:1839–1845. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN C.C., HSIAO L.D., CHIEN C.S., LEE C.W., HSIEH J.T., YANG C.M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human tracheal smooth muscle cells: involvement of p42/p44 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-kappaB. Cell. Signal. 2004;16:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU L., PAUL A., MACKENZIE C.J., BRYANT C., GRAHAM A., PLEVIN R. Nuclear factor kappa B is involved in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated induction of interferon regulatory factor-1 and GAS/GAF DNA-binding in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1629–1638. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUO S.F., WANG C.C., CHIEN C.S., HSIAO L.D., YANG C.M. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 by lipopolysaccharide in canine tracheal smooth muscle cells: involvement of p42/p44 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways. Cell. Signal. 2003;15:497–509. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKENZIE C.J., PAUL A., WILSON S., DE MARTIN R., BAKER A.H., PLEVIN R. Enhancement of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated JNK activity in rat aortic smooth muscle cells by pharmacological and adenovirus-mediated inhibition of inhibitory kappa B kinase signalling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;139:1041–1049. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADRID L.V., MAYO M.W., REUTHER J.Y., BALDWIN A.S., JR Akt stimulates the transactivation potential of the RelA/p65 Subunit of NF-kappa B through utilization of the Ikappa B kinase and activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18934–18940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYEUX P.R. Pathobiology of lipopolysaccharide. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 1997;51:415–435. doi: 10.1080/00984109708984034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MERCURIO F., ZHU H., MURRAY B.W., SHEVCHENKO A., BENNETT B.L., LI J., YOUNG D.B., BARBOSA M., MANN M., MANNING A., RAO A. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF-kappaB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–866. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONACO C., ANDREAKOS E., KIRIAKIDIS S., MAURI C., BICKNELL C., FOXWELL B., CHESHIRE N., PALEOLOG E., FELDMANN M. Canonical pathway of nuclear factor kappa B activation selectively regulates proinflammatory and prothrombotic responses in human atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:5634–5639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401060101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLER J.M., ZIEGLER-HEITBROCK H.W., BAEUERLE P.A. Nuclear factor kappa B, a mediator of lipopolysaccharide effects. Immunobiology. 1993;187:233–256. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICKLIN S.A., BAKER A.H.Simple methods for preparing recombinant adenoviruses for high efficiency transduction of vascular cells Vascular Disease: Molecular Biology and Gene Transfer Protocols (Methods in Molecular Medicine) 1999New York, NY: Humana Press; Baker, A.H. ed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'CONNELL M.A., BENNETT B.L., MERCURIO F., MANNING A.M., MACKMAN N. Role of IKK1 and IKK2 in lipopolysaccharide signaling in human monocytic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30410–30414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'NEILL L. The Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain: a molecular switch for inflammation and host defence. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2000;28:557–563. doi: 10.1042/bst0280557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'NEILL L.A. Signal transduction pathways activated by the IL-1 receptor/toll-like receptor superfamily. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;270:47–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OITZINGER W., HOFER-WARBINEK R., SCHMID J.A., KOSHELNICK Y., BINDER B.R., DE MARTIN R. Adenovirus-mediated expression of a mutant IkappaB kinase 2 inhibits the response of endothelial cells to inflammatory stimuli. Blood. 2001;97:1611–1617. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAUL A., BRYANT C., LAWSON M.F., CHILVERS E.R., PLEVIN R. Dissociation of lipopolysaccharide-mediated induction of nitric oxide synthase and inhibition of DNA synthesis in RAW 264.7 macrophages and rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997a;120:1439–1444. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAUL A., DOHERTY K., PLEVIN R. Differential regulation by protein kinase C isoforms of nitric oxide synthase induction in RAW 264.7 macrophages and rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997b;120:940–946. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PINGLE S.C., SANCHEZ J.F., HALLAM D.M., WILLIAMSON A.L., MAGGIRWAR S.B., RAMKUMAR V. Hypertonicity inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide synthase expression in smooth muscle cells by inhibiting nuclear factor kappaB. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:1238–1247. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PLEVIN R., SCOTT P.H., ROBINSON C.J., GOULD G.W. Efficacy of agonist-stimulated MEK activation determines the susceptibility of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase to inhibition in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem. J. 1996;318 Part 2:657–663. doi: 10.1042/bj3180657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POLTORAK A., HE X., SMIRNOVA I., LIU M.Y., VAN HUFFEL C., DU X., BIRDWELL D., ALEJOS E., SILVA M., GALANOS C., FREUDENBERG M., RICCIARDI-CASTAGNOLI P., LAYTON B., BEUTLER B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAO K.M. Molecular mechanisms regulating iNOS expression in various cell types. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B. Crit. Rev. 2000;3:27–58. doi: 10.1080/109374000281131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RATTAN R., GIRI S., SINGH A.K., SINGH I. Rho A negatively regulates cytokine-mediated inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in brain-derived transformed cell lines: negative regulation of IKKalpha. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;35:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REGNIER C.H., SONG H.Y., GAO X., GOEDDEL D.V., CAO Z., ROTHE M. Identification and characterization of an IkappaB kinase. Cell. 1997;90:373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80344-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTHWARF D.M., KARIN M. The NF-kappa B activation pathway: a paradigm in information transfer from membrane to nucleus. Sci. STKE. 1999;1999:RE1. doi: 10.1126/stke.1999.5.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHREIBER E., MATTHIAS P., MULLER M.M., SCHAFFNER W. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts', prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6419. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWABE R.F., BENNETT B.L., MANNING A.M., BRENNER D.A. Differential role of I kappa B kinase 1 and 2 in primary rat hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2001;33:81–90. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.20799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENFTLEBEN U., CAO Y., XIAO G., GRETEN F.R., KRAHN G., BONIZZI G., CHEN Y., HU Y., FONG A., SUN S.C., KARIN M. Activation by IKKalpha of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Science. 2001;293:1495–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1062677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SWANTEK J.L., TSEN M.F., COBB M.H., THOMAS J.A. IL-1 receptor-associated kinase modulates host responsiveness to endotoxin. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4301–4306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKEDA K., TAKEUCHI O., TSUJIMURA T., ITAMI S., ADACHI O., KAWAI T., SANJO H., YOSHIKAWA K., TERADA N., AKIRA S. Limb and skin abnormalities in mice lacking IKKalpha. Science. 1999;284:313–316. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKEUCHI O., AKIRA S. Toll-like receptors; their physiological role and signal transduction system. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:625–635. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TORRIE L.J., MACKENZIE C.J., PAUL A., PLEVIN R. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated inhibitory kappa B kinase activity in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:393–401. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WORONICZ J.D., GAO X., CAO Z., ROTHE M., GOEDDEL D.V. IkappaB kinase-beta: NF-kappaB activation and complex formation with IkappaB kinase-alpha and NIK. Science. 1997;278:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO K., ARAKAWA T., UEDA N., YAMAMOTO S. Transcriptional roles of nuclear factor kappa B and nuclear factor-interleukin-6 in the tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in MC3T3-E1 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:31315–31320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAMOTO Y., VERMA U.N., PRAJAPATI S., KWAK Y.T., GAYNOR R.B. Histone H3 phosphorylation by IKK-alpha is critical for cytokine-induced gene expression. Nature. 2003;423:655–659. doi: 10.1038/nature01576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG C.M., CHIEN C.S., HSIAO L.D., LUO S.F., WANG C.C. Interleukin-1beta-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression is mediated through activation of p42/44 and p38 MAPKS, and NF-kappaB pathways in canine tracheal smooth muscle cells. Cell Signal. 2002;14:899–911. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG R.B., MARK M.R., GURNEY A.L., GODOWSKI P.J. Signaling events induced by lipopolysaccharide-activated toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 1999;163:639–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG G., GHOSH S. Molecular mechanisms of NF-kappaB activation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide through Toll-like receptors. J. Endotoxin. Res. 2000;6:453–457. doi: 10.1179/096805100101532414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHAO Q., LEE F.S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinases 2 and 3 activate nuclear factor-kappaB through IkappaB kinase-alpha and IkappaB kinase-beta. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8355–8358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]