Abstract

The mechanical and dynamical properties of the actin network are essential for many cellular processes like motility or division, and there is a growing body of evidence that they are also important for adhesion and trafficking. The leading edge of migrating cells is pushed out by the polymerization of actin networks, a process orchestrated by cross-linkers and other actin-binding proteins. In vitro physical characterizations show that these same proteins control the elastic properties of actin gels. Here we use a biomimetic system of Listeria monocytogenes, beads coated with an activator of actin polymerization, to assess the role of various actin-binding proteins in propulsion. We find that the properties of actin-based movement are clearly affected by the presence of cross-linkers. By monitoring the evolution of marked parts of the comet, we provide direct experimental evidence that the actin gel continuously undergoes deformations during the growth of the comet. Depending on the protein composition in the motility medium, deformations arise from either gel elasticity or monomer diffusion through the actin comet. Our findings demonstrate that actin-based movement is governed by the mechanical properties of the actin network, which are fine-tuned by proteins involved in actin dynamics and assembly.

INTRODUCTION

Actin polymerization generates the force necessary for lamellipodial membrane extension at the leading edge of migrating cells. How this force is produced, however, is still an open question. The actin cytoskeleton underlying the lamellipodium forms a highly cross-linked network (1). Importantly, cross-linkers are necessary for efficient force generation by actin networks: cells depleted in the cross-linking protein filamin, for example, do not form lamellipodia, but produce spherical bare membrane protrusions called blebs (2). The importance of actin cross-linkers suggests that the elasticity of the actin network plays an important role in force generation within cells.

Actin polymerization can also propel bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes and endosomes inside cells (3–5). In simplified systems, bacteria, beads, liposomes, and oil droplets can likewise move in cell extracts or in a medium containing a minimum set of purified proteins (6–11). The cargos are covered with nucleation factors, which activate actin polymerization at their surface. Actin filaments then grow and form a cross-linked gel around the object. In many cases, the actin shell is polarized from the beginning: bacteria and liposomes are often asymmetrical, polarity being imposed during bacterial division or during liposome formation (3,5,9). However, even for symmetrical objects, such as uniformly-coated beads, the gel can spontaneously break, leading to the formation of an actin comet that propels the object forward (12).

Beads propelled by actin polymerization have been widely used as a model system for Arp2/3-dependent actin-based movement. The molecular basis of this movement is now well understood (13). Once activated at the bead surface by a Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein, the Arp2/3 complex nucleates new filaments as branches on preexisting filaments, thus leading to the formation of a dendritic actin network. Capping protein or gelsolin limits the growth of actin filaments to a region close to the bead surface, while actin depolymerizing factor (ADF)/cofilin regulates filament depolymerization at the minus end of filaments. Together with profilin, these proteins cooperate to ensure a high level of ATP-coupled actin monomers for further polymerization (14). Cross-linking proteins modulate the physical properties of the actin network and the time necessary for comet formation increases with their concentration (12). The interplay of all these ingredients ensures the continuous growth of the actin network from the bead surface providing the forces needed for movement.

Various physical models have been proposed to explain how actin polymerization can generate forces (15–17). It is now well documented that the elastic properties of actin gels are responsible for symmetry breaking (12,18). The role of elasticity for bead movement, however, is still under discussion, although several observations suggest that the comet exerts elastic stresses on the bead during its movement (8–11). Here, we use a simple assay where beads coated with verprolin/cofilin/acidic domain (VCA), an Arp2/3 activator derived from Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein, move in a mixture of commercially available purified proteins, and we study the influence of cross-linkers and of bead size on the velocity. By photobleaching fluorescent actin to mark regions in the gel, or by using successively two different actin markers, we also provide direct evidence that the actin gel in the comet undergoes deformations that relax as the comet grows. These observations can be accounted for by a model in which the elastic properties of the actin network and diffusion of actin monomers result in strains in the comet that relax as the comet grows.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins

Actin, Arp2/3, gelsolin, ADF/cofilin, profilin, α-actinin, VCA, and biotinylated actin were purchased from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO), and used without further purification. Protein concentrations were determined by SDS-PAGE using a BSA standard. Alexa Fluor 594-labeled actin (red actin) and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled actin (green actin) were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and streptavidin from PerBio Science (Brebières, France). Fascin was purified as described in Vignjevic et al. (19). Human filamin A was a gift of F. Nakamura and T. Stossel (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA).

Bead preparation and motility assay

Polystyrene beads (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) of different radii were coated with VCA (at complete saturation) as described previously (12), and stored in a storage buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mg/ml BSA) for up to one week. F-actin was prepared by adding 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.1 M KCl, and 1 mM MgCl2 to a solution of G-actin. Unless otherwise stated, the motility medium contained 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 1.8 mM Mg-ATP, 6 mM DTT, 0.13 mM Dabco (an anti-photobleaching agent), 8.1 μM F-actin (10% labeled with Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 488), 0.1 μM Arp2/3, 0.35 μM gelsolin, 3 μM ADF/cofilin, 1 μM profilin, and 10 mg/ml BSA. Samples were prepared by diluting a small volume of bead suspension 30 times in the motility medium, and placed between a glass slide and coverslip (18 × 18 mm) sealed with vaseline/lanolin/paraffin (1:1:1). The total sample volume was such that the spacing between slide and coverslip was at least three times the bead diameter. The comet length was measured as a function of time for 8–12 different beads. Since no significant depolymerization was observed during the experiment for the ADF/cofilin concentration used, the average bead velocity could be estimated as the average rate of increase of the comet length.

Bead observation and data processing

Phase contrast and fluorescence microscopy were performed using an Olympus inverted microscope with a 100× oil immersion objective (Olympus, Rungis, France). Confocal microscopy experiments were carried out with a Zeiss confocal microscope with a 63× 1.4 NA oil immersion Plan-Apochromat objective, and controlled by LSM 510 META software (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Actin-Alexa Fluor 488 was observed with an Ion Argon 25mW laser (488 nm) at 0.3–2% of the laser power. For photobleaching, 100% of the laser power was used. Image contrast was reprocessed using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, Downington, PA).

Determination of G-actin concentration in the medium

The motility medium, in the presence or absence of cross-linkers, was left at room temperature for 20 min and centrifuged at 150,000 × g during 45 min to sediment F-actin. The actin concentration in the supernatant (G-actin) was determined by Western blot using a monoclonal anti-actin, mouse IgG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Viscosity measurements

Viscosity measurements were performed by immersing BSA-coated beads of different radii (R = 1–4 μm) in the motility medium and observing their Brownian motion using bright-field microscopy. The mean-square displacement of the beads, 〈r2〉, increased linearly as a function of time: 〈r2〉 = 6Dt, where D is the diffusion coefficient of the beads. The viscosity η was calculated from the slope of this line using the Stokes-Einstein relation: D = kT/6πηR.

RESULTS

Bead velocity depends on bead radius and actin gel properties

We study the steady-state movement of beads coated with the actin nucleator VCA and placed in a medium containing actin and ATP, the Arp2/3 complex, gelsolin, ADF/cofilin, and profilin. Reoptimization of concentrations using current batches of commercial proteins defined an optimal mix of 8.1 μM actin, 0.1 μM Arp2/3, 0.8 μM gelsolin, 1 μM profilin, and 5 μM ADF/cofilin, which gives a velocity of 0.7 μm/min for 1.5-μm radius beads (see Supplementary Material Fig. S1).

The effect of the bead radius on the velocity depends on the concentration of gelsolin in the medium (Fig. 1 a). At 0.35 μM gelsolin, the velocity decreases approximately as 1/R, whereas at higher gelsolin concentrations the effect of the radius on the velocity is much smaller. For 0.73 μM gelsolin, the velocity is almost constant for radii smaller than 2.5 μm, and it is only ∼25% lower for 5-μm radius beads.

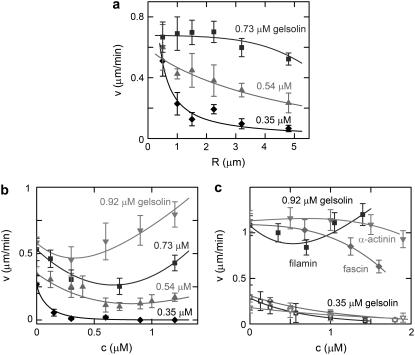

FIGURE 1.

Bead velocity depends on bead radius and on the presence of cross-linkers. Beads were incubated in a medium containing 8.1 μM F-actin (10% labeled with Alexa Fluor 594), 0.1 μM Arp2/3, 3 μM ADF/cofilin, 1 μM profilin, and various concentrations of gelsolin. (a) The average velocity as a function of the bead radius for gelsolin concentrations of 0.35 μM (solid diamonds), 0.54 μM (shaded triangles), and 0.73 μM (squares). The data for 0.35 μM is fitted with v = 0.25/R (χ2 = 0.0019). Other continuous lines are to guide the eyes. (b) The average velocity of 1.5-μm radius beads as a function of the concentration of streptavidin in the presence of 2.5 μM biotinylated actin (30% of total actin) for gelsolin concentrations of 0.35 μM (solid diamonds), 0.54 μM (shaded triangles), 0.73 μM (squares), and 0.92 μM (light shaded down-triangles). (c) The effect of the cross-linkers filamin (squares), α-actinin (light shaded down-triangles), and fascin (shaded diamonds) on the average velocity of 1.5-μm radius beads for gelsolin concentrations of 0.35 μM (open symbols) and 0.9 μM (solid symbols).

To understand how the bead velocity is affected by the gel elastic properties, we investigated the effect of actin filament cross-linking on the bead movement. First, we used the nonphysiological cross-linker streptavidin in combination with biotinylated actin (30% of total actin). As for variations in bead radius, the effect of cross-linkers depends on the concentration of gelsolin in the medium (Fig. 1 b). At 0.35 μM gelsolin, the bead velocity decreases monotonically as a function of the amount of streptavidin in the medium. At this concentration of gelsolin, no symmetry breaking could be observed for streptavidin concentrations above 1 μM (the bead velocity is zero). At higher gelsolin concentrations, the velocity passes through a minimum as a function of streptavidin concentration. The minimum shifts to lower streptavidin concentrations with increasing amounts of gelsolin. Qualitatively the same results were found with the physiological network-forming protein filamin, while for the actin-bundling proteins α-actinin and fascin only a decrease in velocity could be observed (Fig. 1 c). We checked that the effect of cross-linkers was not due to a change in the bulk properties of the medium affecting either the availability of G-actin monomers or the viscosity of the solution. The concentration of G-actin in the bulk in the presence and in the absence of cross-linkers was measured by centrifuging the samples and determining the G-actin concentration in the supernatant using Western blot analysis. No significant change in the monomer concentration was observed after the addition of cross-linkers (within the measurement error of ±50%, see Supplementary Material Fig. S2). The effect of cross-linkers on the viscosity was measured by monitoring the Brownian motion of suspended BSA-coated beads. In the mixture of purified proteins but in the absence of streptavidin the measured diffusion coefficient is approximately three times smaller than that of beads in the buffer, indicating that the motility medium is three times more viscous than the buffer. Surprisingly, after the addition of streptavidin, the sample viscosity was found to decrease and was almost equal to that of a buffer at 0.8 μM streptavidin (see Supplementary Material Fig. S3).

Evolution of a newly-grown actin layer

Elastic stresses that build up in the actin gel are responsible for symmetry breaking and comet formation (12). To determine if stresses are still present after symmetry breaking in a growing comet, we monitored the evolution of a newly-grown layer of actin at a stage when the comet was already formed: we used successively two different actin markers during the comet growth. Our first attempt was to add actin of a different color to a mixture containing beads with comets. This experimental way was not satisfactory, since actin comets appeared inhomogeneous by phase contrast microscopy, probably due to a sudden increase in total actin concentration. We decided to use a different experimental approach that would preserve the homogeneity of the comet. Beads placed in a medium containing red actin (10% of total actin) and beads placed in a medium containing green actin (10%) were incubated separately at room temperature. After 45 min, the two preparations were added together and gently mixed. No change of the structure of the comet could be seen in phase contrast using this approach (Fig. 2 a). The evolution of a newly inserted actin layer was monitored by observing the interface between red and green actin in the comet using fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2). Our observations clearly show that the red/green actin interface undergoes deformations. The radius of curvature of this interface is initially that of the bead, and then increases as the actin grows from the bead surface. This effect is more pronounced near the sides of the comet (Fig. 2 a). The red-green interface stops changing shape when the layer is further than approximately one-bead's diameter from the bead surface (see Supplementary Material Movie 1). These results provide evidence for deformations in the actin comet during bead motion. No significant difference was observed in the shapes of the red-green interfaces at 0.2, 0.35, or 0.92 μM gelsolin (Fig. 2, b and c).

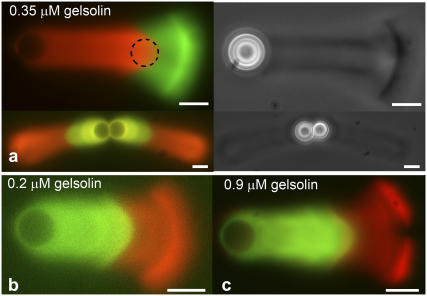

FIGURE 2.

A two-color assay shows deformations in the gel during comet growth. Beads with a radius of 2.25 μm were incubated with a different actin marker during the initial stages than during the later stages of comet growth. The overlays of green and red fluorescent images are shown. (a) Deformations at 0.35 μM gelsolin. The initially spherical gel layer close to the bead surface is deformed during comet growth and increases its radius of curvature, especially near the sides of the comet. The dashed circle indicates the shape of the bead. In phase-contrast, no change in structure is seen at the interface of green and red actin (pictures on the right), thus validating that the experimental procedure does not change the steady-state regime. Similar deformations are observed at gelsolin concentrations of 0.2 μM (b) and 0.9 μM (c). Other protein concentrations: 8.1 μM F-actin (10% labeled), 0.1 μM Arp2/3, 3 μM ADF/cofilin, and 1 μM profilin. Scale bar is 5 μm in all figures. A movie showing the deformation is shown in Supplementary Material (Movie 1).

Evolution of lines in the comet

To further investigate the deformations of the actin gel in the comet, we photobleached lines of various orientations and at various distances from the bead and monitored their evolution as the comet grew. The results are displayed in Fig. 3. A line of gel perpendicular to the comet axis is strongly deformed as the comet grows, as long as the line is less than one-bead's diameter from the bead surface. Perpendicular lines further away from the bead surface do not display any deformation, showing that the elastic stresses are relaxed at this distance (Fig. 3 a). Perpendicular regions bleached at the bead surface show similar deformations (Fig. 3 b). The shapes of the lines in Fig. 3, a and b, suggest that the deformation occurs mainly parallel to the comet axis, i.e., that the gel flows mainly along the axis of the comet (in the reference frame of the bead). To evaluate directly the perpendicular velocity component we photobleached parallel lines in comets (Fig. 3 c). Contrary to perpendicular lines, parallel lines are not deformed as the comet grows, indicating that the perpendicular component of the velocity in the actin gel is negligible compared to the parallel component.

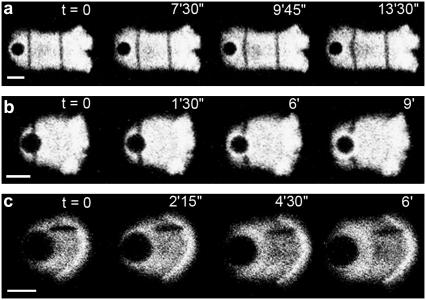

FIGURE 3.

Photobleaching shows deformations in the gel during comet growth. (a, b) Lines bleached perpendicular to the comet axis are deformed when the lines are less than a bead-diameter away from the bead surface. Lines further away are not deformed (a). (c) Lines bleached parallel to the comet axis are barely deformed during comet growth. Protein concentrations: 8.1 μM F-actin (10% labeled with Alexa Fluor 488), 0.1 μM Arp2/3, 3 μM ADF/cofilin, 1 μM profilin, and 0.3 μM gelsolin. Scale bar is 5 μm in all figures.

Hence, different points of the gel move (in the reference frame of the bead) mainly along the axis of the comet, albeit at different velocities, depending on their distance from the comet edges. Actin filaments in the center of the comet move more slowly than those in the outer regions of the comet. A line perpendicular to the axis of the comet at the surface of the bead bends ∼15° as the comet evolves (Fig. 3 a).

DISCUSSION

It is well established that the actin comet behaves like an elastic gel (20,21). As a result, deformations in the gel result in elastic stresses that may affect the movement of the beads. Although elastic stresses have been shown to be important for symmetry breaking (12), for squeezing of vesicles or oil droplets by actin tails (9–11), and for the hopping motion of beads (8), their role in motility and their effect on speed remain under discussion. The deformations in the gel (Figs. 2 and 3) and the effect of cross-linkers (Fig. 1, b and c) provide support for a role of elasticity in actin-based propulsion.

Elastic model for bead movement

Polymerization at the bead surface pushes away older gel layers, resulting in an accumulation of elastic stress due to bead curvature (22). Relaxation of this elastic stress as the bead moves forward results in an effective propulsive force Fel ∼ Eh3/R (23), where E is the elastic modulus of the gel, h the thickness of the gel on the side of the bead, and R the bead radius (see Fig. 4 b). The propulsive force is opposed by a friction force Ffr ∼ γvR2, where γ is a friction coefficient per unit area, which can be related to the kinetics of attachment and detachment of filaments (24). The bead velocity v follows from the balance between elastic and friction forces.

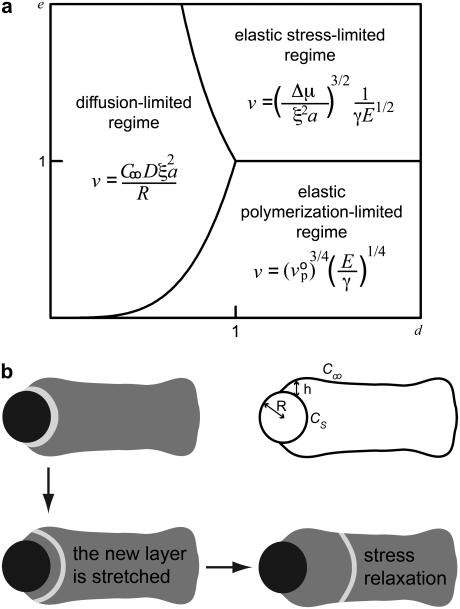

FIGURE 4.

Diffusion versus elasticity. (a) State diagram showing the three regimes of bead motion as a function of the dimensionless modulus e and the dimensionless diffusion coefficient d. The transition between diffusion and polymerization-limited regimes occurs for e = d 4, that between diffusion and stress-limited regimes for e = d −2, and that between polymerization and stress-limited regimes for e = 1. (b) Schematic depiction of stress-relaxation leading to deformations in the actin gel. A spherical gel layer accumulates stress as the gel polymerizes, which is relaxed when the gel reduces its curvature and, as a result, its area. The upper right picture in panel b indicates the parameters for the description of the movement.

If the elastic modulus E is small enough, the polymerization rate is not modified by the stress and the gel thickness h is given by the polymerization rate in the absence of stress  multiplied by the time R/v spent by the gel at the surface of the bead:

multiplied by the time R/v spent by the gel at the surface of the bead:  (20,24). This gives the velocity

(20,24). This gives the velocity

|

(1) |

For higher elastic moduli, the accumulated elastic stress may limit actin polymerization at the surface. In this case, the gel thickness saturates at a value close to the stress-limited steady-state thickness of the gel before symmetry breaking (22):  , with Δμ the chemical energy of the polymerization reaction, and σ0 a characteristic stress for the variation of the polymerization velocity with stress. The characteristic stress σ0 is related to the mesh size ξ of the actin network, and the size a of an actin monomer by

, with Δμ the chemical energy of the polymerization reaction, and σ0 a characteristic stress for the variation of the polymerization velocity with stress. The characteristic stress σ0 is related to the mesh size ξ of the actin network, and the size a of an actin monomer by  . In this limit, the velocity is approximately

. In this limit, the velocity is approximately

|

(2) |

The transition between these two regimes occurs when the modulus E reaches the value for which the velocities given by Eqs. 1 and 2 are equal and will be discussed further below.

Velocity is limited by diffusion and by elasticity at low and high gelsolin concentrations, respectively

In both the polymerization-limited (low E) and stress-limited (high E) regimes, the elastic propulsion model predicts that the velocity does not depend on the bead radius. This is indeed what we observe at high gelsolin concentrations: at 0.73 μM gelsolin, the velocity is independent of the radius for radii smaller than 2.5 μm (Fig. 1 a), in agreement with previous observations (25). However, at lower gelsolin concentrations, we observe a decrease in the velocity with increasing radius (0.35 μM and 0.54 μM gelsolin in Fig. 1 a). To account for this R-dependency, we must take into account the fact that monomers consumed during polymerization have to diffuse to the bead surface and that this can significantly reduce the actin monomer concentration inside the comet if the actin meshwork is dense enough (26,27). The diffusive flux of monomers toward the bead surface at the center of the comet can be approximated as  , with D the diffusion coefficient of monomers in the gel and C∞ and CS the monomer concentrations at the exterior surface of the comet and at the bead surface at the center of the comet, respectively (see Fig. 4 b). We assume that monomer diffusion in the bulk of the solution is fast, so that the actin monomer concentration outside the gel is approximately equal to the concentration in the bulk. At steady state, the diffusive flux is equal to the monomer consumption per unit area, JP = kCS/ξ2 with k the polymerization rate constant (which depends on the local stress at the rear of the bead), and ξ the distance between growing filaments (of the order of the mesh size of the gel). The steady-state monomer concentration is then

, with D the diffusion coefficient of monomers in the gel and C∞ and CS the monomer concentrations at the exterior surface of the comet and at the bead surface at the center of the comet, respectively (see Fig. 4 b). We assume that monomer diffusion in the bulk of the solution is fast, so that the actin monomer concentration outside the gel is approximately equal to the concentration in the bulk. At steady state, the diffusive flux is equal to the monomer consumption per unit area, JP = kCS/ξ2 with k the polymerization rate constant (which depends on the local stress at the rear of the bead), and ξ the distance between growing filaments (of the order of the mesh size of the gel). The steady-state monomer concentration is then

|

(3) |

which shows that diffusion becomes limiting for D ≪ kR/ξ2. At the center of the comet, the polymerization velocity vp = kCSa must equal the velocity of the bead, so that in the diffusion-limited regime the speed is

|

(4) |

Our results for 0.35 μM gelsolin (Fig. 1 a) can be fitted by Eq. 4, giving C∞Dξ2a ≈ 0.25μm2/min. With D = 2μm2/s (26), C∞ = 1 μM (measured by Western blot, see Supplementary Material Fig. S2), and a = 2.7 nm, the fitted value gives ξ = 36 nm, in agreement with estimates from electron micrographs (26). Under these conditions, taking k = 12 μm−1 s−1 = 0.02 μm3 s−1 (28), the dimensionless parameter Dξ2/kR varies between 0.13 and 0.026 for radii between 1 and 5 μm, which is consistent with our assumption of diffusion-limited kinetics (D ≪ kR/ξ2).

Diffusion versus elasticity

The curves shown in Fig. 1 a are well accounted for by a diffusion-limited regime at low gelsolin concentration and an elasticity-dominated regime at high gelsolin concentration. This effect of gelsolin can be explained by its capping activity. At higher gelsolin concentrations, the number of growing actin filaments is smaller due to increased capping, therefore the mesh size ξ is larger. This is supported by the observation that the gel is less dense for higher gelsolin concentrations, as seen from the fluorescence intensity of the comet (see Supplementary Material Fig. S4). Above a critical mesh size  , elasticity becomes dominant. Assuming that D and k do not vary significantly, we find ξc = 100 nm for R = 1 μm and ξc = 224 nm for R = 5 μm, which is in the experimentally accessible range (22,26). Note that the diffusion coefficient D could also increase with the mesh size, which would reduce ξc.

, elasticity becomes dominant. Assuming that D and k do not vary significantly, we find ξc = 100 nm for R = 1 μm and ξc = 224 nm for R = 5 μm, which is in the experimentally accessible range (22,26). Note that the diffusion coefficient D could also increase with the mesh size, which would reduce ξc.

The above discussion shows the existence of three distinct regimes for bead movement: a diffusion-limited regime (velocity given by Eq. 4) and two elastic regimes where diffusion is not rate-limiting, corresponding to low gel elastic moduli where the thickness is limited by polymerization (Eq. 1) and high elastic moduli where the thickness is limited by the elastic stresses (Eq. 2). The actual state of the system is determined by eight variables that can be recast into two reduced variables: a dimensionless modulus  and a dimensionless diffusion coefficient

and a dimensionless diffusion coefficient  , where

, where  is the actin polymerization velocity in the absence of any external stress when the monomer concentration is C∞. The details of the derivation of e and d are given in Appendix A. The e–d plane is divided into three different regions corresponding to the three regimes discussed above. As explained in Appendix A, the transition between the polymerization-limited regime and the stress-limited regime occurs at e = 1. If e < 1, the crossover between the diffusion-limited regime and the polymerization-limited regime occurs when e = d 4, and when e > 1, the transition between the stress-limited regime and the diffusion-limited regime occurs when e = d−2. Any experiment where one of the parameters e or d is varied can be considered as a curve in this diagram along which the velocity varies. Note that varying the bead radius changes only the coordinate d, and that it corresponds to a horizontal line in the diagram.

is the actin polymerization velocity in the absence of any external stress when the monomer concentration is C∞. The details of the derivation of e and d are given in Appendix A. The e–d plane is divided into three different regions corresponding to the three regimes discussed above. As explained in Appendix A, the transition between the polymerization-limited regime and the stress-limited regime occurs at e = 1. If e < 1, the crossover between the diffusion-limited regime and the polymerization-limited regime occurs when e = d 4, and when e > 1, the transition between the stress-limited regime and the diffusion-limited regime occurs when e = d−2. Any experiment where one of the parameters e or d is varied can be considered as a curve in this diagram along which the velocity varies. Note that varying the bead radius changes only the coordinate d, and that it corresponds to a horizontal line in the diagram.

Velocity is affected by the elastic modulus

We observe that the presence of cross-linkers changes the speed of the beads (Fig. 1, b and c). This effect could result from depletion of available actin monomers, since cross-linking might stabilize actin filaments and thus prevent depolymerization in the bulk solution (29). However, our measurements of the G-actin concentration in the samples show that the presence of cross-linkers does not change G-actin concentration within the experimental error (see Supplementary Material Fig. S2). Moreover, a decrease in monomer concentration would imply a decrease in velocity and could not account for the velocity increase observed at high gelsolin and cross-linker concentration. Nor can the velocity variations be accounted for by a change in the medium viscosity. Indeed, the medium viscosity is at most three times higher than that of the buffer and it decreases by roughly a factor of 3 after addition of cross-linkers (see Supplementary Material Fig. S3), probably because the medium becomes inhomogeneous due to local bundling of actin filaments leading to a lower F-actin concentration elsewhere. Given that the force generated by the growing comet is in the nanoNewton range (20), and that the viscous drag force is of the order of 10 femtoNewtons (16), we conclude that the viscous force is negligible compared to the polymerization force in our experiments. It therefore seems likely that the effects of cross-linkers on bead velocity are due to a change in the elastic properties of the actin comet.

At 0.35 μM gelsolin, the velocity decreases strongly after addition of cross-linkers for all four cross-linkers (Fig. 1, b and c). As indicated by the radius dependence shown in Fig. 1 a, the speed is limited by diffusion at this gelsolin concentration when no cross-linkers are present. If the system stays in the diffusion-limited regime, the strong decrease in velocity suggests a decrease in the diffusion coefficient when cross-linkers are added. This effect might be a consequence of a decrease in the mesh size upon addition of cross-linkers, thus preventing diffusion of monomers through the gel. Alternatively, the decrease in velocity can be explained by a crossover to the stress-limited regime (Fig. 4 a): assuming that the addition of cross-linkers mainly increases the elastic modulus E, we move in the positive e-direction in the state-diagram upon addition of cross-linkers. At e = d−2, there is a crossover from the diffusion-limited to the stress-limited regime. After the crossover, the velocity decreases with the elastic modulus as v ∼ E−1/2 (Eq. 2).

At higher gelsolin concentration, diffusion is not rate-limiting (see above), and the effect of cross-linkers is different than at low gelsolin concentration. Upon addition of streptavidin and filamin, the bead velocity first decreases and then strongly increases (Fig. 1, b and c). The increase in the velocity at high cross-linker concentrations can be explained by an increased modulus (Eq. 1), and provides strong support for the elastic propulsion mechanism where one expects v to vary as E1/4 when the gel thickness is determined by the polymerization rate. However, the comparison between experiments and the predicted scaling laws can only remain qualitative since the exact relation between the modulus E, the friction coefficient γ, and the concentration of cross-linkers is not known. Nevertheless, the increase in velocity upon addition of cross-linkers indicates that we are in the polymerization-limited regime (e < 1) at high gelsolin concentration, probably because the friction coefficient γ is small due to a low number of attached filaments on the surface. It remains unclear as to why the velocity decreases at lower amounts of cross-linkers, but this might be due to an increase of the friction coefficient upon filament bundling close to the surface (Eq. 1). One could expect that for very high cross-linker concentration (and thus modulus E), the system would reach e = 1 and crossover to the stress-limited regime, leading to a decreasing velocity (Fig. 4 a). We have not observed such a decrease in our experiments, however. The reason why e does not increase sufficiently to reach the transition might be that e varies proportionally to Eξ4, so that an increase in E upon addition of cross-linkers is counterbalanced by a decrease in ξ.

For α-actinin and fascin, we do not observe an enhancement of the movement, probably because their effects on the modulus and the stresses in the gel are smaller. Note that the effect of these bundling proteins for symmetry breaking was also much smaller than that of biotin/streptavidin or filamin (12).

Effect of elasticity and diffusion on deformations in the gel

The observation of a newly-grown actin layer in the two-color experiment shows that deformations in the comet occur at low as well as at high gelsolin concentrations (Fig. 2). Indeed, both diffusion and elastic properties of the comet can account for the deformations observed.

In the diffusion-limited regime, polymerization at the center of the comet is slow due to a reduced supply of monomers, while polymerization at the sides of the comet, which can be easily reached by monomers, is faster. As a result, in the reference frame of the bead, the gel moves faster in the outer part of the comet than in the central part. This accounts for the deformations of bleached vertical lines that deform as whiskers (Fig. 3) as well as for the observation that new-grown actin layers open up and reduce their curvature (Fig. 2).

In the elasticity-dominated regime, as actin polymerizes at the bead surface in a perpendicular direction, it pushes away older gel layers, resulting in an accumulation of elastic stress due to the bead curvature (22). A newly-grown gel layer is thus first stretched because new material is continuously added at the bead surface leading to stresses in the layer. As the layer gets further away from the bead surface, it can reduce these stresses by reducing its area. Given the geometry of the comet, a decrease in area is achieved by reducing the layer curvature (Fig. 4 b). This is what we observe in the two-color experiments (Fig. 2), and is also supported by the photobleaching experiments, where a perpendicular line turns into a curved line oriented with its concavity toward the comet extremity (Fig. 3). In Appendix B, we propose a more detailed elastic model for a thin layer of gel on the bead surface that accounts for the deformation of lines bleached when the gel is still around the bead.

In most cases, probably both diffusion and elasticity contribute to the deformations observed. Importantly, both mechanisms result in strains and therefore elastic stresses in the actin gel. The stresses relax as the comet grows and no deformation is observed further than approximately one-bead's radius from the bead surface (see Fig. 2 b, Fig. 3, and Supplementary Material Movie 1).

Actin-based motility within cells

Listeria monocytogenes or endosomes move within cells by activating actin polymerization at their surface. Since a cell is not a homogeneous medium and is constantly remodeling its cytoskeleton, it is essential to understand the behavior of such intracellular motile objects under different conditions. The bead system is a powerful tool for this, because it allows for a systematic variation of parameters like the bead size or the presence of various actin-binding proteins. From the present work, we know that objects of different sizes move at the same speed if the diffusion coefficient of actin monomers is sufficiently high (see Eq. 4). Under such conditions, the speed will only be affected in cellular regions where actin-binding proteins like cross-linkers or branching agents are effective. On the other hand, if actin monomer diffusion through the comet is impeded for example by transient interactions with the comet actin network, large objects will move more slowly than small objects. This effect of actin monomer diffusion might explain why two different experiments give apparently contradictory results on the effect of size on speed (7,25).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

We show here that during bead movement, the actin comet undergoes deformations over a lengthscale that is of the order of the bead diameter. The actin gel is under stress, due either to growth limitations through monomer diffusion, or to pure elasticity caused by the curvature. Our velocity measurements are consistent with a state diagram defined by an effective elastic modulus and an effective diffusion coefficient. By varying parameters like the size of the beads and the concentration of cross-linkers or regulating proteins, we move within the state diagram, passing from one regime to another. Our approach paves the way for a detailed description of all actin-based motile systems, where diffusion, friction, and elasticity have to be taken into account.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Plastino for help with the Western blot, for the fascin purification, and for many useful discussions. We also thank Fumi Nakamura and Thomas Stossel for the gift of filamin, and Richard Dickinson for sending us a preprint of his work.

This work was supported by a La Ligue Contre le Cancer fellowship (to E.P.), a Human Frontier Science Program fellowship (to J.v.d.G.), a Curie Program Incitatif Coopératif grant, and a Human Frontiers Science Program grant (to C.S.).

APPENDIX A: DERIVATION OF THE STATE DIAGRAM

The values of the variables characterizing the experimental system, and in particular the elastic modulus of the actin comet, E, and the diffusion coefficient of monomers through the actin network, D, determine the movement regime. Depending on these parameters, the system can be in the diffusion-limited regime or in one of the two elastic regimes (polymerization- or stress-limited).

The crossover from the elastic polymerization-limited regime (corresponding to small elastic moduli E) to the elastic stress-limited regime (high E) occurs when the elastic modulus reaches the value for which the velocities given by Eqs. 1 and 2 are equal:

|

Introducing a dimensionless elastic modulus e,

|

(5) |

the crossover corresponds to e = 1. If diffusion is not dominant (high diffusion coefficient D), when e < 1, the system is in the elastic polymerization-limited regime and when e > 1, the system is in the elastic stress-limited regime.

The crossover between the elastic polymerization-limited regime and the diffusion-limited regime occurs when the velocities given by Eqs. 1 and 4 are equal,

|

i.e.,

|

(6) |

We then introduce a dimensionless diffusion coefficient d:

|

(7) |

Using e and d, Eq. 6 simply reads e = d 4.

Finally, the crossover between the elastic stress-limited regime and the diffusion-limited regime occurs when the velocities given by Eqs. 2 and 4 are equal,

|

which, with the use of e and d, simply reads e = d −2.

These relations determine the boundaries between the three regimes of movement. When e < 1 and e < d 4, the system is in the elastic polymerization-limited regime. When e > 1 and e > d −2, the system is in the elastic stress-limited regime. Otherwise, the system is in the diffusion-limited regime. Thus, the values of the dimensionless coefficients e and d fully determine the regime in which the system resides. These results are summarized in a state diagram in the (e–d) plane, where each couple of coordinates (e, d) corresponds to a set of experimental conditions (Fig. 4 a).

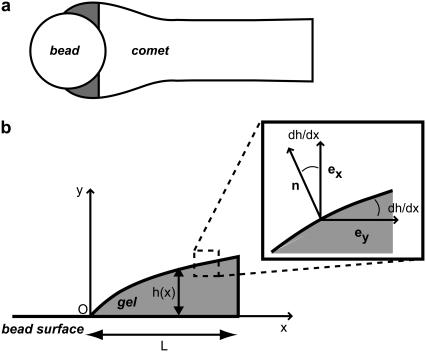

APPENDIX B: VELOCITY FIELD IN A THIN LAYER OF GEL AT THE BEAD SURFACE

To calculate the velocity field inside the gel around the bead, we propose a model for a thin actin layer at the bead surface, describing the gel as an elastic material. Focusing on the piece of gel that is around the bead (shaded zone in Fig. 5 a) and assuming that the comet has reached a steady-state regime, we develop a two-dimensional model in which the bead surface is approximated by a plane. We have checked that a three-dimensional model of a gel on a cylindrical surface leads to similar results. We assume that the gel thickness is small compared to the bead radius, in agreement with experimental observations (see, e.g., Figs. 2 and 3) and we consider that actin polymerizes perpendicularly to the bead surface with a constant polymerization velocity vp, equal to the polymerization velocity in the absence of stress  .

.

FIGURE 5.

Notations for the thin layer model. (a) The model focuses on the part of the comet close to the bead surface, marked in shaded representation. (b) Reference frame and notations used in the model.

Using Cartesian coordinates in a reference frame in which the bead does not move, we call h(x) the gel thickness at x and L the width of the zone in which actin polymerizes (as sketched in Fig. 5 b). The width L is of the order of the bead radius R, and h(x) is small compared to L.

The constitutive equations of the elastic material are given by  , where σij is the deviatory stress tensor related to strains of the fluid elements, and eij = 1/2(∂jvi + ∂ivj) is the velocity-gradient tensor (30,31) (in the convective derivative D/Dt, we ignore the rotational contribution associated to the vorticity that turns out small). For a two-dimensional gel, only the components exx, exy = eyx, and eyy of the velocity-gradient tensor do not vanish. Then, in a steady state, the constitutive equations give three relations:

, where σij is the deviatory stress tensor related to strains of the fluid elements, and eij = 1/2(∂jvi + ∂ivj) is the velocity-gradient tensor (30,31) (in the convective derivative D/Dt, we ignore the rotational contribution associated to the vorticity that turns out small). For a two-dimensional gel, only the components exx, exy = eyx, and eyy of the velocity-gradient tensor do not vanish. Then, in a steady state, the constitutive equations give three relations:

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

The total stress tensor is given by σij − p δij where p is the pressure, and the local force balance equation reads as

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

Finally, we consider the gel as an incompressible fluid so that  .

.

On the bead surface, we suppose that there is viscous friction with a friction coefficient per unit area γ and that the polymerized material is not under tension so that, at y = 0, σxx − p = 0, and σxy = γvx. At the outer surface of the gel, the normal component of the stress tensor vanishes. In a thin film approximation, the angle between the free surface and the x axis, dh/dx, is small (Fig. 5 b), and we have the following limit conditions at y = h(x):

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

Since lines along the x axis do not deform during comet growth (Fig. 3 c), the component vx of the velocity mainly accounts for the observed deformations. As h ≪ L, we expand all quantities in powers of y. This approximation is supported by the experimental observation that a line along the y axis bleached at the surface of the bead, remains straight during comet growth: an expansion of vx up to first-order in y is therefore sufficient to account for the deformation (Fig. 3 b). We write vx = v0 + β(x)y and σxx – p = s(x)y.

The incompressibility condition gives the perpendicular velocity  , and the actin mass conservation imposes a relation between the velocity and the local thickness: v0(x)h(x) = vpx, where we have chosen the origin of the coordinate x at the contact line between the comet and the bead. The transverse stress σxy can be determined from Eq. 11:

, and the actin mass conservation imposes a relation between the velocity and the local thickness: v0(x)h(x) = vpx, where we have chosen the origin of the coordinate x at the contact line between the comet and the bead. The transverse stress σxy can be determined from Eq. 11:  .

.

A first relation between the velocity v0 and the normal stress coefficient s is then obtained from the boundary condition for the normal stress equation, Eq. 13:

|

(15) |

A second relation between s(x) and v0 is obtained by first calculating the normal stress  from Eqs. 12 and 14 and then using the constitutive Eqs. 8 and 10:

from Eqs. 12 and 14 and then using the constitutive Eqs. 8 and 10:

|

(16) |

Combining these two relations, we derive a differential equation for the velocity v0(x):

|

(17) |

This equation can be solved by introducing the variable  . In the limit where V ≫ 1, the solution is

. In the limit where V ≫ 1, the solution is

|

with θ the contact angle between the comet surface and the x axis (the bead) at the front of the gel (as shown in Fig. 5 b), and a the size of a monomer.

Dimensional analysis of Eq. 17 gives  , and

, and  (actin flux conservation). If the angle θ is not small (which seems true experimentally; the theoretical derivation of θ would require a detailed description of the crossover to the cylindrical comet behind the bead, which is beyond the scope of this work), V2(a) ≫ 1. Since x/a is at most of the order of 1000 (a = 2.7 nm and L ∼ R ∼ 2.5 μm), we thus have V2(x) ≫ 1, which is consistent with our assumptions. Note that the scaling law that we obtain is slightly different form that obtained in the elastic scaling model presented in the text. This is probably due to the thin film approximation used here.

(actin flux conservation). If the angle θ is not small (which seems true experimentally; the theoretical derivation of θ would require a detailed description of the crossover to the cylindrical comet behind the bead, which is beyond the scope of this work), V2(a) ≫ 1. Since x/a is at most of the order of 1000 (a = 2.7 nm and L ∼ R ∼ 2.5 μm), we thus have V2(x) ≫ 1, which is consistent with our assumptions. Note that the scaling law that we obtain is slightly different form that obtained in the elastic scaling model presented in the text. This is probably due to the thin film approximation used here.

The velocity then reads

|

(18) |

The coefficient β that gives the variation of the velocity in the y direction perpendicular to the bead is directly deduced from v0 by writing the constitutive Eq. 9 for y = 0:

|

(19) |

We thus find that β is positive, which is in agreement with experimental observations. Indeed, vx = v0 + βy, with ν > 0, implies that the gel in the external part of the comet moves with a higher velocity than the gel close to the bead surface, leading to deformations in the same direction as those observed experimentally (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 b).

E. Paluch and J. van der Gucht contributed equally to this article.

E. Paluch's present address is Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, Dresden, Germany.

J. van der Gucht's present address is Laboratory of Physical Chemistry and Colloidal Science, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Svitkina, T. M., and G. G. Borisy. 1999. Arp2/3 complex and actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin in dendritic organization and treadmilling of actin filament array in lamellipodia. J. Cell Biol. 145:1009–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham, C. C., J. B. Gorlin, D. J. Kwiatkowski, J. H. Hartwig, P. A. Janmey, H. R. Byers, and T. P. Stossel. 1992. Actin-binding protein requirement for cortical stability and efficient locomotion. Science. 255:325–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tilney, L. G., D. J. DeRosier, and M. S. Tilney. 1992. How Listeria exploits host cell actin to form its own cytoskeleton. I. Formation of a tail and how that tail might be involved in movement. J. Cell Biol. 118:71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theriot, J. A., T. J. Mitchison, L. G. Tilney, and D. A. Portnoy. 1992. The rate of actin-based motility of intracellular Listeria monocytogenes equals the rate of actin polymerization. Nature. 357:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merrifield, C. J., S. E. Moss, C. Ballestrem, B. A. Imhof, G. Giese, I. Wunderlich, and W. Almers. 1999. Endocytic vesicles move at the tips of actin tails in cultured mast cells. Nature Cell. Biol. 1:72–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loisel, T. P., R. Boujemaa, D. Pantaloni, and M.-F. Carlier. 1999. Reconstitution of actin-based motility of Listeria and Shigella using pure proteins. Nature. 401:613–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron, L. A., M. J. Footer, A. Van Oudenaarden, and J. A. Theriot. 1999. Motility of ActA protein-coated microspheres driven by actin polymerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:4908–4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernheim-Groswasser, A., S. Wiesner, R. M. Golsteyn, M.-F. Carlier, and C. Sykes. 2002. The dynamics of actin-based motility depend on surface parameters. Nature. 417:308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upadhyaya, A., J. R. Chabot, A. Andreeva, A. Samadani, and A. Van Oudenaarden. 2003. Probing polymerization forces by using actin-propelled lipid vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:4521–4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giardini, P. A., D. A. Fletcher, and J. A. Theriot. 2003. Compression forces generated by actin comet tails on lipid vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:6493–6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boukellal, H., O. Campàs, J.-F. Joanny, J. Prost, and C. Sykes. 2004. Soft Listeria: actin-based propulsion of liquid drops. Phys. Rev. E. 69:061906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van der Gucht, J., E. Paluch, J. Plastino, and C. Sykes. 2005. Stress release drives symmetry breaking for actin-based movement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:7847–7852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollard, T. D., and G. G. Borisy. 2003. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 112:453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pantaloni, D., C. Le Clainche, and M.-F. Carlier. 2001. Mechanism of actin-based motility. Science. 292:1502–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mogilner, A., and G. Oster. 2003. Force generation by actin polymerization: the elastic ratchet and tethered filaments. Biophys. J. 84:1591–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plastino, J., and C. Sykes. 2005. The actin slingshot. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogilner, A. 2006. On the edge: modeling protrusion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18:32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekimoto, K., J. Prost, F. Jülicher, H. Boukellal, and A. Bernheim-Groswasser. 2004. Role of tensile stress in actin gels and a symmetry-breaking instability. Eur. Phys. J. E. 13:247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vignjevic, D., D. Yarar, M. D. Welch, J. Peloquin, T. Svitkina, and G. G. Borisy. 2003. Formation of filopodia-like bundles in vitro from a dendritic network. J. Cell Biol. 160:951–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcy, Y., J. Prost, M.-F. Carlier, and C. Sykes. 2004. Forces generated during actin-based propulsion: a direct measurement by micromanipulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:5992–5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerbal, F., V. Laurent, A. Ott, M.-F. Carlier, P. Chaikin, and J. Prost. 2000. Measurement of the elasticity of the actin tail of Listeria monocytogenes. Eur. Biophys. J. 29:134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noireaux, V., R. M. Golsteyn, E. Friederich, J. Prost, C. Antony, D. Louvard, and C. Sykes. 2000. Growing an actin gel on spherical surfaces. Biophys. J. 78:1643–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerbal, F., P. Chaikin, Y. Rabin, and J. Prost. 2000. An elastic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes propulsion. Biophys. J. 79:2259–2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerbal, F., V. Noireaux, C. Sykes, F. Jülicher, P. Chaikin, A. Ott, J. Prost, R. M. Golsteyn, E. Friederich, D. Louvard, V. Laurent, and M.-F. Carlier. 1999. On the Listeria propulsion mechanism. Pramana J. Phys. 53:155–170. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiesner, S., E. Helfer, D. Didry, G. Ducouret, F. Lafuma, M.-F. Carlier, and D. Pantaloni. 2003. A biomimetic motility assay provides insight into the mechanism of actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 160:387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plastino, J., I. Lelidis, J. Prost, and C. Sykes. 2004. The effect of diffusion, depolymerization and nucleation promoting factors on actin gel growth. Eur. Biophys. J. 33:310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickinson, R. B., and D. L. Purich. 2006. Diffusion rate limitations in actin-based propulsion of hard and deformable particles. Biophys. J. 91:1548–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollard, T. D. 1986. Rate constants for the reactions of ATP- and ADP-actin with the ends of actin filaments. J. Cell Biol. 103:2747–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tilney, L. G., P. S. Connelly, L. Ruggiero, K. A. Vranich, and G. M. Guild. 2003. Actin filament turnover regulated by cross-linking accounts for the size, shape, location, and number of actin bundles in Drosophila bristles. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:3953–3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyon, E., J.-P. Hulin, L. Petit, and C. D. Mitescu. 2001. Physical Hydrodynamics. Oxford University Press, New York.

- 31.Landau, L. D., and E. M. Lifchitz. 1986. Theory of Elasticity. Course of Theoretical Physics, Vol. 7. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK.