Abstract

Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) can enhance the proliferative capacity of bone and bone marrow stromal cells; however, the mechanisms behind this effect are not well described. We present a whole-cell kinetic model relating receptor-mediated binding, internalization, and processing of FGF2 to osteoblastic proliferative response. Focusing on one of the potential signaling complex stoichiometries, we utilized experimentally measured and modeled estimated rate constants to predict in vitro proliferation and distinguish between potential binding orders. We found that piecewise assemblage of a ternary signaling complex may occur in several ways depending on the local binding environment. Using experimental data of endocytosed FGF2 as a constraint, we have also shown evidence of potential multistep processes involved in heparan-sulfate proteoglycans-bound FGF2 release, internalization, and fragment formation in conjunction with the normal metabolism of the proteoglycan.

INTRODUCTION

The ease with which bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) can be isolated from a patient and expanded in vitro, combined with their robust osteoblastic lineage potential (1), make them an attractive cell source for bone tissue engineering research. However, upon in vitro expansion, the proliferation rate (2) and bone-forming efficiency of BMSCs (3) decreases with increasing passage number. These limitations have caused concern regarding the use of BMSCs in clinical applications. There have been a number of studies investigating various biological additives to help overcome these shortcomings (4–6). Of particular multifaceted benefit, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) enhances the osteogenic potential of BMSCs (7) and extends their lifespan (8) as well as proliferative capacity (7,8). As part of our program in bone tissue engineering, we have developed a whole-cell kinetic model to investigate the mechanisms through which FGF2 induces bone and BMSC proliferation. By continuing to gain insight on dynamic receptor-ligand interactions and subsequent cellular response, researchers will eventually develop a systematic framework through which to maximize, exploit, and control the use of FGF2 in bone tissue engineering applications.

Fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) is a pluripotent and pleiotropic member of a family of polypeptides that regulate cell-growth and differentiation, play a major role in tissue development, tissue repair, and tissue regeneration, and are implicated in a number of pathologies (9). FGF2 is mitogenic for several cells of mesodermal, ectodermal, and endodermal origin (10). Several mathematical models have surfaced on FGF2 binding, providing information on: the impact of heparan-sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) on FGF2-FGFR binding (11); translocation through the basement membrane (12); how HSPG regulates and impacts FGFR binding (13); FGF2 signaling pathways (14); receptor interactions in signaling (15); receptor preassociation (16); signal complex assembly (17); and the correlation between surface-binding kinetics and the activation of downstream mediators of response (18). The model presented here focuses on, but is not limited to, the impact of FGF2 on primary and BMSC-derived osteoblast proliferation. This article will explore the use of kinetic constants derived from osteoblastic and other mesodermal cells in a whole-cell kinetic model to determine if they can be used to predict average in vitro bone cell mitogenic response and to explore the intracellular fate of FGF2.

Exogenous 18-kDa FGF2 stimulation of proliferation occurs through dimerization of high affinity fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) (19). This low molecular mass form of FGF2 is known to act in an autocrine/paracrine manner (20). Higher molecular-weight isoforms of FGF2 (22, 22.5, 24, and 34 kDa) are localized in the nucleus, are not released from the cell, and act through intracrine mechanisms (21–24). Five FGFRs have been identified (25,26), with FGFR1–4 containing intracellular tyrosine kinase domains. FGF2 also interacts with a class of low-affinity receptors, the heparin-like glycosaminoglycan component of heparan-sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs). HSPGs/heparin are involved in the signaling complex that promotes mitogenesis (27–29) without directly altering the signal transduction pathways activated by occupied FGFRs (30). Ligand-induced receptor dimerization and subsequent autophosphorylation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domains initiates multiple signal-transduction pathways. Several of these pathways may be interdependent (31) and a number of parallel pathways likely contribute to mitogenic signal transduction (32). Dimerization of FGFRs by FGF2 is known to activate several mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways including the extracellular signal-related kinases 1 and 2 (ERK 1/2) (31), which are involved in the regulation of mitosis (28,33,34). The exact schema of intracellular signaling events leading to FGF2-induced proliferation remains illusive. In this article, we will focus on the salient ligand and receptor trafficking events that initiate the signaling pathways leading to mitogenesis, rather than the signaling cascades themselves.

All receptor tyrosine kinases are activated by dimerization (35), however, the specific mechanisms through which FGF receptor dimerization is achieved are not clear (32), nor is receptor activation alone enough to stimulate 18 kDa FGF2-induced proliferation (36). After activation and ligand-induced receptor endocytosis, exogenous FGF2 has been shown to accumulate in the nucleus (37). Nuclear translocation of FGF2 has been implicated as a requirement for exogenous growth factor-induced mitogenic activity (38,39). This is suggestive of an intracrine growth-promoting effect of exogenous FGF2, which is synergistic with its autocrine-signaling mechanisms (40). FGFRs have been found to translocate to the nuclear membrane in response to FGF2 stimulation (41–43), where they are involved in the regulation of cell proliferation (44). HSPGs have also been implicated in FGF2 nuclear transport (45,46).

Three potential stoichiometries accounting for a signaling complex involving FGFR dimerization have been suggested. Crystal structure models for the two prototypic members of the FGF family have been solved involving an FGF/heparin/FGFR signaling complex with a 2:2:2 (using FGF2) (47) and 2:1:2 (48,49) (using FGF1) stoichiometry. In addition, an alternate model based on biophysical analysis suggests a ternary complex in which FGF2-bound HSPG promotes FGFR dimerization (1:1:2) (50). In this article, we will focus on the 2:2:2 stoichiometry and reserve the other configurations for future examination. The authors of the 2:2:2 crystal structure model (47) suggest that heparin interacts with both FGF and FGFR to form a stable 1:1:1 ternary complex which is subsequently recruited by an additional 1:1:1 complex to form the signaling unit. Here, we constructed a model to evaluate three potential binding orders for the formation of a 1:1:1 complex en route to receptor dimerization. We used kinetic rate constants found in the literature (when available) to compare mitogenic signaling complex formation in each binding order to an average proliferative dose response observed in osteoblastic cells. We have included an intracellular component to this model to reconstruct potential intracellular trafficking events based on the limited knowledge available regarding the destiny of endocytosed FGF2. In addition, model predictions of cell-surface and media-excreted HSPG concentrations are compared to experimental values found in the literature.

The whole-cell kinetic model presented in this article is able to predict average proliferative dose-response values for osteoblastic cells in vitro. Using experimental proliferation data collected in this lab and in the literature as a constraint, we used the model to estimate kinetic rate constants not available within the literature and evaluated their physiological relevance. We assessed estimated kinetic rate constants as well as cell model variables such as cell density, receptor ratio, and the capacity of HSPG-ligand binding for their ability to influence proliferation predictions. We found, given the literature and estimated kinetic rate values, that each binding configuration could be of physiological relevance and that the mode of signaling complex formation may depend on the given local binding environment—including the number, type, and distribution of receptors. We also explored implications that the presence and structure of HSPGs may play an important role in the regulation of FGF2-mediated proliferative response and bioavailability of the growth factor. Intracellularly, it appears that there may be multistep processes involving the endocytosis and processing of FGF2 at high concentrations. Taken together, this cellular model provides a succinct means of exploring the relevance of both established and estimated kinetic rate constants on the formation and subsequent internalization of an FGF2-induced proliferative signaling complex. It is the first model of its kind to incorporate the intracellular processing of FGF2 and utilize an experimentally observed commonality in proliferative dose response across two types of bone cells in two species as an analytical constraint for surface-binding events. As modeling in this field grows, this type of analysis of the complex FGF-FGFR system may eventually provide a means of understanding, controlling, and manipulating this signaling process for the benefit of biological, engineering, and clinical sciences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental methods

Cell isolation and culture

Marrow and bone cells were isolated from the tibias and femurs of young male New Zealand White rabbits (average 1.67 kg). Bone marrow cavity contents were aseptically removed and harvested in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium containing 50 μg/mL gentamicin. Marrow was passed through 18- and 20-gauge needles and resuspended in medium containing Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2.5 mM L-glutamine, and 50 μg/mL gentamicin. To induce osteogenic differentiation, media also was supplemented with 10−8 M dexamethasone, 50 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and 3 mM β-glycerophosphate (BMSC growth media). Nucleated hematopoietic and stromal cells were plated in tissue culture polystyrene flasks at 6.7 × 105 cells/cm2. Cells were cultured in a humidified 37°C/5% CO2 incubator. BMSC were selected based on their ability to adhere to the flask; nonadherent hematopoietic cells were removed upon reseeding after 24 h. Medium was replaced twice weekly until the cells reached confluence (∼2.5 weeks), detached using a 0.25% trypsin/1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution, and counted using a Coulter Counter (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL).

Periosteum and adherent tissue were removed from rabbit tibial and femoral bone chips with a scalpel and rinsed in phosphate buffered saline without calcium and magnesium. Chips were subjected to three sequential collagenase digestions (50 mg collagenase, 50 ml phosphate buffered saline, and 2.5 ml FBS filtered through 0.8 mm then 0.2 mm filters) for 30 min each in a water bath (37°C). Cell pellets were collected after centrifugation at 2000 RPM for 3 min. The first pellet, primarily fibroblastic cells (51), was discarded. The remaining two digestions were plated in tissue culture polystyrene flasks with HAM's F-12 media supplemented with 10% FBS, 2.5 mM L-glutamine, and 3 mM β-glycerophosphate (bone cell growth media) at 1 × 104 cells/cm2. Medium was replaced twice weekly until the cells reached confluence (∼2 weeks), detached using a 0.25% trypsin/0.02% EDTA solution, and counted using a Coulter Counter.

FGF2 proliferation dose response

Rabbit bone cells and BMSCs were plated in 24 well plates at 1 × 104 cells/cm2 in cell growth media and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Media then was replaced with fresh cell growth media supplemented with various doses of FGF2 (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ng/ml). After five days of exposure, FGF2 supplemented media was replaced with fresh cell growth media without FGF2. On day seven, cells were detached using a 0.25% trypsin/0.02% EDTA solution, and counted using a Coulter Counter (n = 4). Results are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Rabbit bone and BMSC proliferative dose response

| FGF2 (ng/ml) | 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | 100 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rabbit bone | 114 × 103 | 125 × 103 | 174 × 103 | 370 × 103* | 464 × 103† | 352 × 103* |

| ±SD | ± 20 × 103 | ± 100 × 103 | ± 17 × 103 | ± 19 × 103 | ± 250 × 103 | ± 83 × 103 |

| Rabbit BMSC | 55 × 103 | 57 × 103 | 79 × 103 | 85 × 103‡ | 140 × 103§ | 104 × 103‡ |

| ±SD | ± 6.0 × 103 | ± 9 × 103 | ± 9 × 103 | ± 9 × 103 | ± 14 × 103 | ± 16 × 103 |

Cells were seeded in 24 well plates at 1 × 104 cells/cm2. Values presented are cell numbers determined through Coulter Counting ± SD after five days of exposure to FGF2, seven days of cell culture (n = 4).

Significantly different than 0 and 0.01 ng/ml doses (p ≤ 0.006).

Significantly different than all doses (p ≤ 0.03).

Significantly different than 0 and 0.01 ng/ml doses (p ≤ 0.03).

Significantly different than all doses (p ≤ 0.004).

Proliferation data was also gathered from previously published experiments performed by other independent laboratories (52,53). In those studies, rat bone marrow stromal cell proliferation was measured by determining cell number using a methylene blue absorbance assay (53). Cells were exposed to growth factor for five days at specified doses cultured for a total of 14 days before data was collected. Rat calvarie data was collected by measuring DNA synthesis through [3H]thymidine incorporation (52). Cells were cultured in the continuous presence of FGF2 at specific doses for 96 h. Cells were exposed to 5 μCi/ml of [3H]thymidine for the last 2 h before data collection.

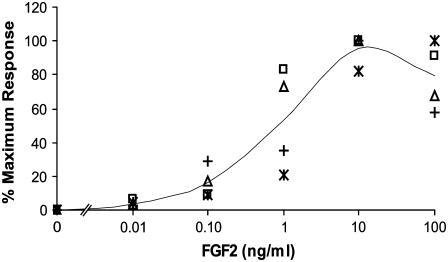

Rat and rabbit bone and bone marrow stromal cell dose response results are presented in Fig. 1 along with their average. To normalize the four sets of data and explore the similar pattern of FGF2 induced proliferative dose response, all data is presented as a percentage of maximum response in cell growth. This experimental average is used to compare model predictions with cell response. The model proposed uses receptor ternary signaling complex occupancy as a means to predict the proliferative response of cells exposed to FGF2. The baseline for the experimentally measured proliferation for cells not exposed to FGF2 (0 ng/ml) was subtracted from experimentally measured values at all doses.

FIGURE 1.

Plot of osteoblastic cell proliferation data. Rat calvarie (*) (52) and rat BMSC (□) (53) data were compiled from literature values. Rabbit bone (▵) and rabbit BMSC (+) data were obtained by the authors. The average of all data (—) was used to compare to model proliferation predictions.

The standard deviation between the values given in Fig. 1 are presented as error bars in Figs. 4–6 and represent the experimental average range in which model predictions are considered to reflect cellular response.

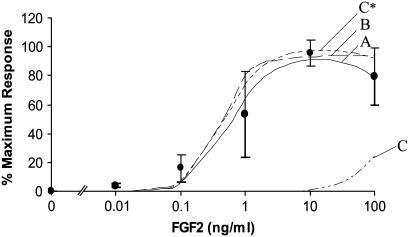

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the dose response proliferation predictions of all models (A–C) to the experimental average (•). Using a slower association and dissociation value for CsHR complexes then measured experimentally (kfc* and krC*) improved Model C proliferation predictions. These results are displayed in Model C*. Predictions are displayed as Model A (—), Model B (– –), Model C (– - - –), and Model C* (—-). Error bars on the experimental average data points represent the standard deviation between experimentally measured proliferation dose responses of rabbit and rat bone and BMSC presented in Fig. 1. These error bars represent the experimental range within which model predictions are considered to reflect actual cellular response.

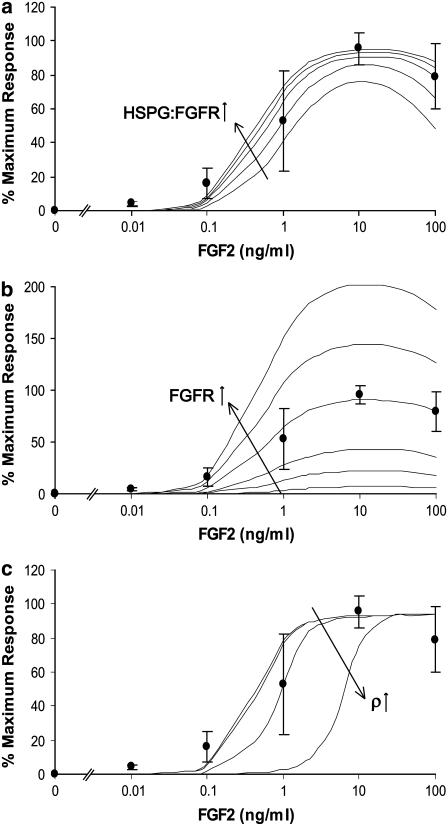

FIGURE 6.

(a) Evaluation of the impact of the ratio of HSPG:FGFR on the proliferative effect of FGF2 on Model A. The experimentally measured ratio of HSPG:FGFR on human bone cells is 8.7:1 (67). Predicted proliferation response increased as the relative number of HSPGs to FGFRs increased (evaluated here at 1:1, 4:1, 8.7:1, 13:1, and 18:1). These results are compared to the experimental average dose response of osteoblastic cells (•). A similar effect was observed in Model B. However, these results were less dramatic in Model C* in which, even at a 1:1 ratio, all of the FGFRs are already constitutively bound to HSPGs. (b) Evaluation of the effect of the number of FGFRs on proliferative response in Model A. All models were sensitive to increases and decreases in FGFR number. FGFR number was evaluated at 0%, 25%, 50%, 100%, 150%, and 200% of value of FGFRs measured on human bone cells (21,500 #/cell) (67). Model A is shown as an example of this receptor's impact. The results are compared to the experimental average dose response of osteoblastic cells (•). (c) Evaluation of the effect of cell density on proliferative response in Model B (ρ = 106, 107, 108, 109, 1010 cell/L). The shift in the proliferation curve with decreased predicted response at several concentrations is observed at very high cell concentrations (ρ = 109 and 1010 cell/L) and is similar in Models A–C*. These results are compared to the experimental average dose response of osteoblastic cells (•).

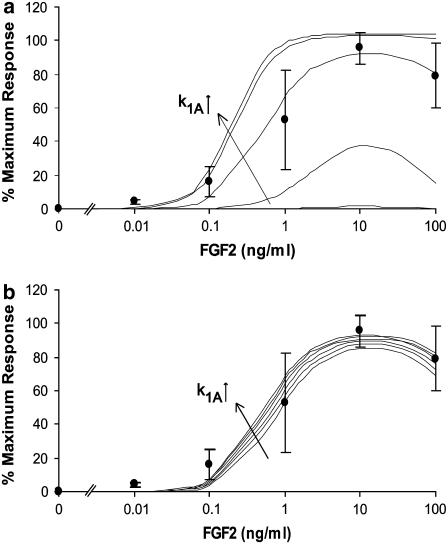

FIGURE 5.

(a) An example of the parametric analyses performed on surface binding constants not found in the literature. This example is for the forward binding of FGF2-FGFR (CsRF) to HSPG (k1A) for Model A. This analysis was performed over a range of 10−3–102 times the initial rate constant estimate, which was along the order of 10−6 (#/cell)−1 min−1. Panel a shows model predicted bone cell proliferative response with 4.3 × 10−9 ≤ k1A ≤ 4.3 × 10−4. (b) Shows model predictions over a range of 2.58 × 10−6 ≤ k1A ≤ 4.73 × 10−6. A value of 3.87 × 10−6 was chosen to use in this model based on a correlation analysis between model predictions and the experimental average proliferative dose response of osteoblastic cells (•) (r = 0.9863).

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance was performed on bone and BMSC dose-response experiments using SYSTAT 11 (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA). Multiple comparisons were performed using a Tukey-Kramer Honestly Significant Difference test. Statistical significance was attained at p ≤ 0.03.

Analytical methods

Surface binding events

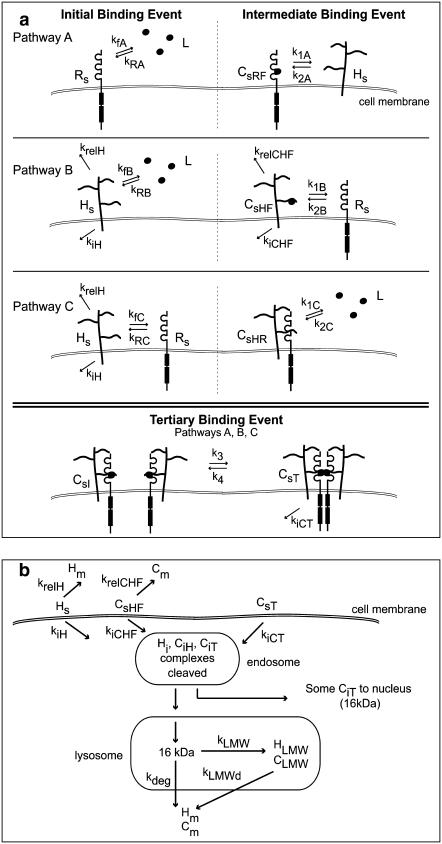

The methodology employed in the model presented here is reviewed elsewhere (54). The three binding pathways leading to the formation of a 2:2:2 signaling complex induced by 18 kDa FGF2 are described in Fig. 3 a. These pathways are evaluated individually to assess their potential to contribute to ternary complex formation. Model terms and related equations are listed in Tables 2 and 3. Certain assumptions have been included in this model. The possibility of different affinities of FGF2 to the various high affinity receptors on the cell surface has been ignored. Instead, a general FGFR is assumed. Although the relative FGF2 induced mitogenic activity of the major splice variants known for FGFRs on BaF3 cells have not been found to be equal (55), the possibility of differences in kinetic binding constants for the various FGFRs exists; this model compares its predictions to experimental data that has been normalized with respect to each data set. This allowed us to exploit common patterns observed in FGF2 induced mitogenesis in osteoblastic cells without constraining our evaluation to a particular cell type or receptor expressed. This also allowed us to simplify model estimations by ignoring potential changes in receptor expression or mitogenic response within a given cell type due to maturation (56–58) or stage of differentiation (59). FGF2 is known to enter cells through both HSPG- and FGFR-mediated pathways (60). The only complexes that are assumed to be internalized are CsHF (FGF2 bound to HSPG) and the ternary signaling complex CsT. Internalization of FGF2 bound to FGFR (CsRF) alone is ignored as it would be subjected to heat, pH, and proteolytic degradation without protection from HSPGs (61,62). In addition, FGF2 has a decreased probability for internalization in the absence of HSPGs and has been found to stimulate mitogenesis in HSPG deficient cells only at nonphysiologic supersaturated concentrations (30). While we do not consider HSPG-bound FGF2 to contribute to mitogenic signaling, it does contribute to the depletion of ligand in the surrounding media as well as intracellular levels of FGF2. For these reasons, equations for the binding and subsequent processing of FGF2 bound HSPGs (CsHF, CiHF) were included in all models. While it is likely that multiple ligands will bind to the heparan sulfate chains on HSPGs as observed with a single heparin (63–65), we assume only one FGF2 to bind to each HSPG for simplicity. Fluid phase FGF2 uptake (66) and the possibility of internalization of the intermediate surface complex (CsI) are ignored. Only one pathway for the formation of ternary complexes from intermediate complexes is evaluated across all models for simplicity.

FIGURE 3.

(a) A schematic representation of the potential binding pathways involved in the piecewise assemblage of a proliferative signaling complex of FGF2/HSPG/FGFR in a 2:2:2 stoichiometry. In all three pathways, binding order of the constituents vary in the initial and intermediate binding steps. In Pathway A, FGF2 (L) binds to FGFR (Rs), forming CsRF, which binds to an HSPG (Hs), to form the intermediate complex (CsI). In Pathway B, FGF2 (L) binds to an HSPG (Hs) forming CsHF, which can be internalized (kiCHF) or released into the medium (krelCHF). CsHF then binds to an FGFR (Rs) to form CsI. In Pathway C, the receptors (Rs and Hs) bind initially to form CsHR, then FGF2 (L) binds to that complex to form the intermediate complex CsI. The tertiary binding event is the same in all pathways—two intermediate complexes bind to form the ternary signaling complex (CsT), which can be internalized (kicT). Cell surface HSPGs can also be internalized (kiH) or released into the surrounding medium (krelH). (b) The potential intracellular processing events of endocytosed FGF2. The growth factor can enter the cell when bound to HSPGs (CsHF) or when part of the ternary signaling complex (CsT). Surface HSPG (Hs) and HSPG-bound FGF2 (CsHF) can also be released into the surrounding medium without being internalized (krelH, krelCHF). Once internalized, the 18 kDa growth factor is cleaved into a 16 kDa form (107). FGF2 in the ternary complex can be transported with its receptors to the nucleus for further signaling. Some internalized (76,103) FGF2 is degraded into low molecular weight fragments (CLMW) before further degradation and subsequent release for the cell. Internalized HSPG (Hi) can also be degraded into low molecular weight fragments (HLMW) before further degradation and subsequent release for the cell.

TABLE 2.

Model equation terms

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Rs | Surface FGFR |

| Hs | Surface HSPG |

| CsRF | Surface FGF2-FGFR complexes |

| CsHF | Surface FGF2-HSPG complexes |

| CsHR | Surface FGFR-HSPG complexes |

| CsI | Surface intermediate complexes (FGF2-HSPG-FGFR) |

| CsT | Surface ternary complexes (CsI-CsI) |

| CiHF | Intracellular FGF2-HSPG complexes |

| Hi | Intracellular HSPG |

| CiT | Intracellular ternary complexes |

| CLMW | Low molecular weight FGF2 fragments (from CiT, CiHF) |

| HLMW | Low molecular weight HSPG fragments (from Hi) |

| Cm | FGF2 degradation products and surface released species |

| Hm | HSPG degradation products and surface released species |

| I(t) | Step function used to alter Hs and CsHF internalization |

| R(t) | Step function used to alter Hs and CsHF release |

| L(t) | Step function used to alter CLMW and HLMW release |

TABLE 3.

Model equations

| Model A | |

| Surface species | dRs/dt = −kfALRs + kRACsRF + 0.11 ks |

| dHs/dt = −k1ACsRFHs + k2ACsI + 0.89 ks − kfBLHs + kRBCsHF − kiHHsI(t) − krelHHsR(t) | |

| dCsRF/dt = kfALRs − kRACsRF − k1ACsRFHs + k2ACsI | |

| dCsHF/dt = kfBLHs − kRBCsHF − kiCHFCsHFI(t) − krelCHFCsHFR(t) | |

|

|

|

|

| (Nav/ρ)dL/dt = −kfALRs + kRACsRF − kfBLHs + kRBCsHF | |

| Model B | |

| Surface species | dHs/dt = −kfBLHs + kRBCsHF + 0.89 ks − kiHHsI(t) − krelHHsR(t) |

| dRs/dt = −k1BCsHFRs + k2BCsI + 0.11 ks | |

| dCsHF/dt = kfBLHs − kRBCsHF − k1BCsHFRs + k2BCsI − kiCHFCsHFI(t) − krelCHFCsHFR(t) | |

|

|

|

|

| (Nav/ρ)dL/dt = −kfBLHs + kRBCsHF | |

| Model C | |

| Surface species | dHs/dt = −kfCRsHs + kRCCsHR + 0.89 ks−kfBLHs + kRBCsHF − kiHHsI(t) − krelHHsR(t) |

| dRs/dt = −kfCRsHs + kRCCsHR + 0.11 ks | |

| dCsHR/dt = kfCRsHs − kRCCsHR−k1CLCsHR + k2CCsI | |

| dCsHF/dt = kfBLHs − kRBCsHF − kiCHFCsHFI(t) − krelCHFCsHFR(t) | |

|

|

|

|

| (Nav/ρ)dL/dt = −k1CLCsHR + k2CCsI − kfBLHs + kRBCsHF | |

| Models A, B, and C | |

| Intracellular species | dCiHF/dt = kiCHFCsHFI(t) − kLMW(1−fCHF)CiHFL(t) − kdegfCHFCiHF |

| dCiT/dt = kiCTCsTI(t) − kLMW(1−fCT)CiTL(t) − kdegfCTCiT | |

| dHi/dt = kiHHsI(t) − kLMW(1−fH)HiL(t) − kdegfHHi | |

| dCLMW/dt = kLMW(1−fCHF)CiHFL(t) + kLMW(1−fCT)CiTL(t) − kLMWdCLMW | |

| dHLMW/dt = kLMW(1−fH)HiL(t) − kLMWdHLMW | |

| dCm/dt = kdegfCHFCiHF + kdegfCTCiT + kLMWdCLMW + krelCHFCsHFR(t) | |

| dHm/dt = kdegfHHi + kLMWdHLMW + krelHHsR(t) | |

| Step FNs | I(t): 0.4 if t ≤ 120, 6 × 10−4t otherwise |

| R(t): 10 if t ≤ 120, 1 otherwise | |

| L(t): 3 if t ≤ 400, 7 otherwise |

The number of FGFRs and HSPGs we employed in this model is shown in Table 4 (67). These values fall within reported ranges for receptor populations on cell surfaces (FGFRs, 0.2–5 × 104 sites/cell; HSPGs, 0.5–2 × 106 sites/cell (68)). Due to high local concentrations of HSPGs and their high affinity to FGFRs, it has been suggested that HSPGs may bind FGFRs constitutively (69). To accommodate this, the initial conditions in pathway C were set so that all of the FGFRs were bound to HSPGs at time t = 0 (Rs = 0, Hs = 166,500; CsHR = 21,500). No whole-cell kinetic constant values could be found in the literature describing the association of FGFRs and native HSPGs. Instead, we took binding constant data for heparin-FGFR1 IIIc (69) and multiplied by the cell density/Avogadro's number (ρ/Nav, see Table 4) to be consistent with the units in the model equations. Model parameters that were not available in the literature including those describing certain surface binding events (k1A, k2A, k1B, k2B, k3, k4), surface release rates (krelCHF, krelH), and HSPG internalization rate (kiH) were estimated based on best fit to the experimental average bone cell proliferation data. A parametric analysis was performed on these rate constants to determine the range of their impact on model predicted outcomes. Constants sensitive to alterations were chosen based on fit to experimental proliferation data as well as the strength of their correlation (r) to the experimental average determined in a correlation analysis. For parameters that did not have a major impact on model predictions, the fastest values were chosen based on evidence of stability (no change in model predictions), fit within experimental average range and correlation. This form of analysis was also performed on the forward and reverse rate constants for in Model C for the binding between HSPG and FGFR (kfC, kRC).

TABLE 4.

Model parameters

| Parameter | Description | Value | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface parameters | |||

| kfA | Forward rate constant, FGF2 binding to FGFR | 2.5 × 108 M−1 min−1 | (79) |

| kRA | Reverse rate constant, FGF2 binding to FGFR | 4.8 × 10−2 min−1 | (79) |

| kfB | Forward rate constant, FGF2 binding to HSPG | 0.9 × 108 M−1 min−1 | (79) |

| kRB | Reverse rate constant, FGF2 binding to HSPG | 6.8 × 10−2 min−1 | (79) |

| kfC | Forward rate constant, HSPG binding to FGFR | 1.89 × 10−10 (#/cell)−1 min−1 | (69) |

| kfC* | Model estimated forward rate constant, HSPG binding to FGFR | 5.67 × 10−7 (#/cell)−1 min−1 | Text |

| kRC | Reverse rate constant, HSPG binding to FGFR | 7.2 × 10−1 min−1 | (69) |

| kRC* | Model estimated reverse rate constant, HSPG binding to FGFR | 1 × 10−3 min−1 | Text |

| k1A | Forward rate constant, FGF2-FGFR (CsRF) binding to HSPG | 3.87 × 10−6 (#/cell)−1 min−1 | Text |

| k2A | Reverse rate constant, FGF2-FGFR (CsRF) binding to HSPG | 1.26 × 10−2 min−1 | Text |

| k1B | Forward rate constant, FGF2-HSPG (CsHF) binding to FGFR | 3.60 × 10−6 (#/cell)−1 min−1 | Text |

| k2B | Reverse rate constant, FGF2-HSPG (CsHF) to FGFR | 1.0 × 10−4 min−1 | Text |

| k1C | Forward rate constant, FGF2 binding to HSPG-FGFR (CsHR) | 2.27 × 108 M−1 min−1 | (79) |

| k2C | Reverse rate constant, FGF2 binding to HSPG-FGFR (CsHR) | 3.0 × 10−3 min−1 | (79) |

| k3 | Forward rate constant, intermediate complex binding (CsI to CsI) | 1 × 101 (#/cell)−1 min−1 | Text |

| k4 | Reverse rate constant, intermediate complex binding (CsI to CsI) | 1 × 10−7 min−1 | Text |

| ks | General receptor synthesis rate | 130 (#/cell) min−1 | (70) |

| krelCHF | Release of surface FGF2-HSPG complexes (CsHF) | 6.25 × 10−4 min−1 | Text |

| krelH | Release of surface HSPGs (Hs) | 5.84 × 10−4 min−1 | Text |

| ρ | Cell density | 107 cell/L | Text |

| Nav | Avogadro's number | 6.02 × 1023 #/mol | |

| Hs | Number of surface HSPGs | 188,000 #/cell | (67) |

| Rs | Number of surface FGFRs | 21,500 #/cell | (67) |

| Internalization parameters | |||

| kiCHF | Surface FGF2-HSPG complex (CsHF) internalization rate constant | 0.0048 min−1 | (76) |

| kiCT | Surface ternary complex (CsT) internalization rate constant | 0.012 min−1 | (76) |

| kiH | surface HSPG (Hs) internalization rate constant | 0.0317 min−1 | Text |

| Intracellular trafficking parameters | |||

| kLMW | Formation of LMW weight intracellular FGF2 fragments (CLMW) | 2.38 × 10−3 min−1 | (76) |

| kLMWd | Degradation of LMW weight intracellular FGF2 fragments (CLMW) | 6.67 × 10−4 min−1 | (76) |

| kdeg | FGF2 degradation rate constant | 7.5 × 10−3 min−1 | (76) |

| fCHF | Fraction of intracellular CiHF sent on an immediate degradation path | 0.6 | Text |

| fCT | Fraction of intracellular CiT sent on an immediate degradation path | 0.6 | Text |

| fH | Fraction of intracellular Hi sent on an immediate degradation path | 1 | Text |

A lumped rate constant has been used for receptor synthesis based on epidermal growth-factor receptor synthesis (70). This constant was multiplied by the proportion of FGFR/HSPG (11:89) expressed on the surface of human bone cells (67). The cell density value (ρ = 107 cells/L) was based on the estimated experimental conditions of referenced articles as well as experiments performed in our laboratory. Ligand recycling is assumed negligible in this model (60). Receptor recycling is also ignored since the recovery of downregulated FGFRs occurs through receptor synthesis, not recycling (71). Finally, internalization of FGF2, through both receptor-mediated (72) and HSPG-mediated (66,73) events, are independent of clathrin-coated pits. Although HSPG-mediated FGF2 internalization has been reported to occur through both noncoated flask-shaped invaginations and caveolae (66), no direct distinction in internalization kinetic rate constants for the specific modes of internalization could be found in the literature. General internalization rates for CsHF (kiCHF) and CsT (kicT) are used.

Internalization and secretion into media of a fraction of cell surface HSPGs is a normal part of cellular HSPG metabolism (74,75). Although no kinetic rate constants were available in the literature for the involvement of these processes in FGF2 metabolism, we assume them to be a relevant aspect of FGF2 metabolism in cells based on the experimental values of FGF2 intracellular localization and excretion into the media by vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (76). Rate constants for the release of HSPG and FGF2-bound HSPG into the media (krelH, krelCHF) and internalization of HSPG (kiH) were estimated and were included in our equations (Table 4) for surface bound HSPGs both with and without bound FGF2.

After comparing model predictions to experimental results, there appeared to be multistep processes involved in the internalization and release of surface HSPGs and HSPG-FGF2 complexes (Hs, CsHF), as well as in HSPG and FGF2 low molecular weight (HLMW, CLMW) fragment formation that were not accounted for by the linear kinetic constants describing those processes (kiCHF, kiH, krelH, krelCHF, kLMW). The step functions I(t), R(t), and L(t) (Table 3) were added to account for these potential processes and fit model predictions to experimental results.

Intracellular processing and media released products

The rate constants used in the intracellular processing component of our model were collected from VSMCs and describe FGF2 complex internalization and degradation, and FGF2 LMW fragment formation and degradation (76) (Fig. 3 b). We converted their data into a percentage of maximum media excreted products. We relate the experimentally determined media excreted and release products to our excreted FGF2 complexes (Cm) resulting from release of surface HSPG-bound FGF2 (CsHF) into the media (krelCHF), degraded intracellular ternary complexes (CiT values) and intracellular FGF2-HSPG complexes (CiHF values), and degraded low molecular weight FGF2 fragments (CLMW values). Intracellular processing in all of the binding orders evaluated in this article is assumed to be the same.

The metabolic processing of HSPGs is also considered in this model. Data was taken from 80 min pulse-chase experiments using rat ovarian granulose cells (74). The time of the radioactive pulse was used to target details regarding the proteoglycan degradation process. HSPG metabolism in Chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cells as determined by 1 h pulse-chase experiments was found to be similar in these cells both with and without exposure to 5 ng/ml FGF2 (77). Results are displayed from these experiments for cells exposed to 5 ng/ml FGF2.

For HSPG metabolism, we relate the experimentally determined media HSPG concentration to our excreted HSPG products (Hm) resulting from release of surface HSPGs (Hs) and HSPG bound FGF2 (CsHF) into the media (krelH, krelCHF), degraded intracellular HSPGs (Hi), ternary complexes (CiT), and intracellular FGF2-HSPG complexes (CiHF), and degraded low molecular weight fragments (HLMW, CLMW). Cell surface HPSGs are related to unbound cell surface HSPGs (Hs) and bound initial, intermediate, and ternary complexes involving HSPGs that have not been internalized (CsHF, CsHR, CsI, CsT).

Fractions were used to divide the internalized complexes into those sent immediately down a degradation pathway (fH, fCHF, fCT) and the amount that remained in the cell longer either to form LMW species (1-fH, 1-fCHF) before degradation or be sent to the nucleus before LMW formation and degradation (1-fCT). Only ternary complexes associated with stimulation of mitogenic response (CiT) are assumed to be translocated to the nucleus. The intracellular destination of endocytosed FGF2/HSPG complexes (CiHF) is different than that of complexes with FGF2/HSPG/FGFRs and has been shown to localize in the nucleus only at very high, nonphysiologic concentrations of FGF2 (2.5 μg/ml) (77). There were no literature values for the kinetic rate constants describing nuclear translocation. Accordingly, we assumed the kinetic constant allocated describing LMW fragment formation and degradation would be inclusive of translocation to and from the nucleus. Sperinde and Nugent (76) note that the rate constant they determined describing the degradation of LMW FGF2 fragments (kLMWd) was an observed rate constant, not a fundamental mass action rate constant. Since observed rate constants are usually a function of several fundamental rate constants (78), it is conceivable that nuclear translocation is accounted for at least by kLMWd.

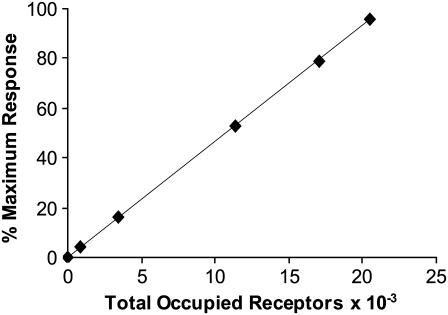

Converting model data to proliferative response

To compare this model to cellular proliferative response data, a correlation had to be drawn between the number of ternary signaling complexes formed and percentage of maximum cellular response. Fannon and Nugent (30) found a near linear relationship between predicted receptor occupancy and DNA synthesis in both normal and heparan sulfate deficient Balb/c3T3 fibroblasts (r = 0.98). Assuming this direct correlation with respect to our model, we multiplied our concentration dependent average percentage of maximum proliferative response of bone and bone marrow derived rat and rabbit osteoblastic cells (Fig. 1) by the number of FGF receptors found on human bone cells (21,500 #/cell) (67), to develop a universal conversion to quantify the total occupied receptor data given by the models in terms of percentage of maximum osteoblastic proliferative response,

|

(1) |

where TOR is the Total Occupied Receptors × 10−3 (R2 = 1) described in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

Correlation between total occupied receptors and percentage of maximum bone cell proliferative response. Average osteoblastic cell proliferative response data was plotted in conjunction with receptor occupancy to create a relationship used to convert model output to proliferative response (% Maximum Response = 4.6512 × (TOR)).

In this model, mitogenic response is assumed to be a function of internalized ternary signaling complexes. Mathcad 11 (Mathsoft Engineering & Education, Cambridge, MA) was used to solve the systems of differential equations presented in this article. The routine rkadapt, which executes a Runge-Kutta method of integration using a nonuniform step size, was used to reach a solution. Simulations were run for a period of 600 min. Since maximal FGFR binding has been observed in Balb/c3T3 cells in ∼180 min (79) and downregulation of HSPGs has been observed in fetal bovine aortic endothelial GM 7373 cells after 6–8 h (80), this was considered more than sufficient time to observe signaling complex formation. Output data from the model provided the number of CT values located on the cell surface and internally. However, since 600 min is not enough time for all of the occupied receptors that have formed ternary complexes to be internalized, surface and internal CT values (CsT and CiT) were used to evaluate a cell's downstream proliferative response.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The high affinity binding observed with FGFRs make them potential candidates for the initial binding event in the formation of a ternary complex. Despite a lower affinity, the increased proportion of HSPG/FGFR make HSPGs potential candidates for the initial site of FGF2 binding as well. Combined with their abundance, the relatively high affinity between HSPGs and FGFR makes constitutive complexes between the two an additional potential candidate for the site of initial FGF2 attachment (69). All three of these modes of initial binding and the implications of the kinetic components used to predict proliferation were evaluated. Each of the three binding pathways is depicted in Fig. 3 a. To predict proliferative response and intracellular FGF2 processing, a set of ordinary differential equations was used to describe each event in each of the models in Fig. 3. Model predictions were compared to an average percentage of maximum osteoblastic cell response (Fig. 1). While the extent of cell proliferation in terms of cell number can vary across cell types as seen in data collected in our laboratory (Table 1), the pattern of proliferative dose response to FGF2 can be similar (Fig. 1). Utilizing a percentage of maximum response allowed us to normalize data collected in our lab and from the literature (52,53) and exploit this pattern of response exhibited across two cell types (bone and BMSCs) in two species (rabbit and rat) in an effort to compare our model predictions to a generalized physical cell response (Fig. 2). Error bars on experimental average data points seen in Figs. 4–6 represent the standard deviation between data points in Fig. 1 and represent a general range of proliferative response at each dose of FGF2 as seen within the cell types and species examined in this analysis. The model terms, parameters, and equations can be found in Tables 2–4, respectively.

Available literature kinetic rate values for the formation of intermediate complexes between heparin and CsRF (FGFR/FGF2 complexes) and FGFR and CsHF (HSPG/FGF2 complexes) were performed using surface plasmon resonance with neoproteoglycan and FGF2 sensor chips (17). These results were inconsistent with whole-cell data for FGF2-FGFR binding (79,81) and with data showing higher FGF2 affinity for the FGFR compared to HSPG (67,79). The differences between the sensor chip's immobilized components and a cell culture or in vivo environment could be the cause of these discrepancies.

Instead, we estimated the intermediate binding rate constants for models A and B (k1A and k1B) by fitting the proliferation predictions to the experimental data. After converting the units by multiplying by Nav/ρ, one can see that these values (2.33 × 1011 and 2.17 × 1011 M−1 min−1 for k1A and k1B, respectively) are considerably faster than the initial forward rate constants, of the order of 108 M−1 min−1 (Table 4), for either model. To test whether or not the constants used could be of physiological relevance, we performed a simple calculation to determine whether the rate constants used would allow enough time for a given receptor to laterally diffuse to its constituent(s) through the plasma membrane. We assigned a hemispherical shape to the average osteoblast with an average cell volume of 910 μm3 (82) giving each an average surface area of 227 μm2. If FGFRs and HSPGs were evenly distributed throughout the surface, there would be an FGFR every 0.011 μm2 and a HSPG every 0.0012 μm2. Lateral diffusion rate constants of the order of 10−9–10−10 cm2/s (83–85) have been measured for various receptors on fibroblast cells using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Since such analysis compiles averages of motion and is not sensitive to the effects of anomalous diffusion (86) that can occur due to factors such as cytoskeletal obstacles (87) or binding (88), we will assume a slower general surface receptor diffusivity coefficient (Ds = 10−11 cm2/s) to test the relevance of the estimated intermediate rate constants. To determine the theoretical area, Ar, in which it would be possible for each receptor to travel during a binding event, we used the relationship Ds/(rsk) ≈ Ar, where rs is the number of surface FGFRs or HSPG receptors, and k is the forward rate constant for CsRF to HSPG or CsHF to FGFR (k1A or k1B). One can see that depending on which receptor diffuses to form the intermediate ternary complex, it would be able to travel within a 0.082–0.775 μm2 area per binding event. This would be a large enough area for any of the receptors to encounter its counterpart, even if the surface receptor diffusivity coefficient was an order-of-magnitude slower (Ds = 10−12 cm2/s), at a minimum establishing plausibility to the model estimated intermediate rate constants. The reverse rate constants were chosen to best fit average experimental proliferation predictions with a maximum correlation coefficient.

The predicted bone cell proliferation for the binding orders described in Fig. 3 a are plotted in Fig. 4. Model C, in which FGFRs are constitutively bound to HSPGs, predicts considerably lower proliferative responses at all doses. Converting the units of the initial forward rate constant in Model C by multiplying by Nav/ρ, the value of kfc is 1.14 × 107 M−1 min−1. This is slower than the initial forward rate constants for both Models A and B, which were measured on whole cells (kfA = 2.5 × 108 M−1 min−1 and kfB = 9 × 107 M−1 min−1). Conversely, the reverse rate constant kRC = 7.2 × 10−1 min−1 is faster than the initial reverse binding rate constants for Models A and B (kRA = 4.8 × 10−2 min−1, kRB = 6.8 × 10−2 min−1). The experiments in which these rate constants were measured were performed with the soluble ectodomains of FGFRs and heparin immobilized on microtiter plates (69). If prebound complexes between HSPGs and FGFRs are of any consequence, it is conceivable that the affinity of these receptors for each other could be greater than that of FGF2 to either receptor. It is also possible that the reverse binding rate constants for these receptors could be slower when the receptors are bound to a cell surface as they are in vitro. By optimizing the forward and reverse binding constants for Model C (using kfC* = 5.67 ± 10−7 (#/cell)−1 min−1, kRC* =1 × 10−3 min−1), we were able to significantly increase the model predicted proliferative response presented in Fig. 4 as Model C* (indicating the use of kfc* and kRC* in Model C). If constitutively bound HSPG/FGFR complexes do in fact play a role in FGF2 induced proliferation, this result indicates that perhaps HSPG/FGFR complexes form more quickly and are more stable on in vitro cell surfaces than in the experimental conditions listed above. However, if the experimentally estimated rate constants do reflect whole-cell kinetic rate constants, then it is not likely that HSPG/FGFR complexes on cell surfaces are a main constituent in the formation of ternary proliferative signaling complexes.

Comparison of experimental and model proliferation results

None of the proposed model binding pathways were successful at predicting bone cell proliferation within the experimental average range at a low concentration of FGF2 (0.01 ng/ml). All experimental proliferation data collected in our lab and by other authors (52,53) were conducted in the presence of serum. Since there are many growth factors in serum (89) including FGF2 (90), this could reflect an additional concentration of FGF2 present under experimental conditions and not accounted for by the model. Alternatively, the model conversion system may not be sensitive enough at low concentrations of FGF2 or the equations used in the models may not accurately represent FGF2 induced bone cell proliferation events at small doses of FGF2. Beyond very low concentrations, the proliferation predictions for Models A and B both lay within the upper and lower limits of the experimental proliferation data for rat and rabbit bone and bone marrow stromal cells (Fig. 1). This makes it impossible to unequivocally identify either as the model for signaling complex formation. The average of the two provides a good fit to the experimental data, indicating that a combination of the two could possibly occur in vitro (data not shown). Utilizing the optimized forward and reverse binding constants (kfC* and kRC*) in Model C* greatly improved proliferation predictions for this binding order. Again, all of the data points, except at 0.01 ng/ml FGF2, fell within the upper and lower limits of the experimental proliferation constraints, making this model also a potential candidate for proliferative signal complex formation.

Parametric analyses

Estimated model parameters describing surface binding events that were not available in the literature (k1A, k2A, k1B, k2B, k3, k4, krelH, krelCHF, kiH) were subjected to a parametric analysis to evaluate their impact on model predicted outcomes. All rate constants were initially estimated based on a fit to the experimental proliferation data. Subsequent analysis involved evaluating predictions over a range of 1/1000th to 1000 times the initial estimate. If parameters demonstrated a sensitivity to alteration based on a comparison to model proliferation predictions and correlation coefficient value, further scrutiny was applied over a smaller range of values to maximize correlation while remaining within the average experimental proliferation range. Rate constants that were common to all models (k3, k4, krelH, krelCHF, kiH) were optimized in Model A. While optimized values were utilized in all other models, they were also subjected to the above-outlined parametric analysis to verify a consistent best fit to the proliferation data.

For Model A, all parameters evaluated (k1A, k2A, k3, k4, krelH, krelCHF, kiH) were sensitive over a range of at least 10−2–100 times initial estimates except for k4. In some cases, this range was greater and the degree to which perturbations in values impacted predictions varied. An example of this analysis for k1A is shown in Fig. 5, a and b. The tertiary reverse rate constant k4 was not very sensitive over a range of 10−3–1000 times the initial estimate (1 × 10−7 min−1). Values faster than or equal to 10−3 min−1 greatly reduced proliferation predictions, and values equal to or slower than 10−7 min−1 did not alter prediction at all. After analysis, this rate constant was chosen to be k4 = 1 × 10−7 min−1 because it was the fastest rate at which stability was observed and marginally increased the fit of model proliferation predictions to the experimental average range. After all optimizations, the final model correlation to the experimental average for Model A was r = 0.9863. In Model B, all rate constants evaluated (k1B, k2B, k3, k4, krelH, krelCHF, kiH) were sensitive over a range of at least 10−2–10 times initial estimates except for k2B and k4. Again, this range was greater in some cases, and the degree to which perturbations in values affected predictions varied. The selection of k4 is outlined above. For the intermediate reverse rate constant k2B, correlation and prediction values did not change much over the broad range of 10−3–1000 times the initial estimate. However, these values were identical from 10−1 to 10−3 times the initial estimate and had a slightly higher correlation. A value of 10−1 times the initial estimate was chosen for the model (k2B = 1.0 × 10−4 min−1) because it was the fastest in this range. The final model correlation to the experimental average for Model B was r = 0.9658.

In Model C, proliferation predictions were well below the experimental range. In this case, a parametric analysis was performed for values found in the literature for HSPG/FGFR binding (kfC, kRC). Both values were sensitive over a range of 10−3–1000 times the literature-measured values (see Table 4). These values were optimized to fit the experimental data (r = 0.9801). A parametric analysis was performed on the remaining constants that were not available in the literature (k3, k4, krelH, krelCHF, kiH). None of the values were sensitive over a range of 10−3–1000 times the optimized values determined from the analysis in Model A. This is likely due to the initial conditions in Model C* that stipulate all of the FGFRs are prebound to HSPG before exposure to FGF2.

Impact of FGF2 binding kinetics on model proliferation predictions

The FGF2 binding rate constants utilized for the initial binding events in Models A and B (kfA, kRA; kfB, kRB) and the intermediate binding event for Model C* (k1C, k2C) were measured on intact cells at a concentration of 0.55 nM FGF2 at 4°C to inhibit internalization (79). However, low temperature evaluation has been shown to significantly decrease the rates of epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization and its dephosphorylation (91). Comparable values using the same FGF2 concentration measured in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) at 37°C were both faster (kfA = 4.2 × 108 M−1 min−1, kRA = 0.79 min−1, k2C = 0.038 min−1) and slower (k1C = 1.2 × 108 M−1 min−1) than values used in this article (81). While these differences could be a function of temperature, they could also be of the cell system used as well as the differences in rending the cells HSPG deficient (chlorate versus heparinase I treatment). Such differences merit investigation. We evaluated the potential impact of both higher and lower FGF2 binding rate constants in all three models. In all models, proliferation predictions were sensitive to increases and decreases in FGF2 binding rate (data not shown). Beyond the potential for physiologic variability in the binding rate constants due to temperature, FGF2 is also known to bind to all FGFRs but with varying affinities (26,55), and HSPGs expressed on different cells can have different abilities to mediate FGFR signaling (92). All of these factors could potentially have a great impact on in vitro cellular response. This model is proposed to evaluate potential binding mechanisms for a generalized average of bone cell proliferation. We acknowledge that such generalizations have implications on predicted response. As more information becomes available within specific cell types (including receptor numbers and types and associated rate constants), this model could be used to obtain specific tangible information regarding binding mechanisms.

Impact of HSPGs and FGFRs on model proliferation predictions

HSPGs might act as dynamic regulators of HS binding proteins, depending on cell environment or status (93). The impact of the ratio of HSPGs to FGFRs is demonstrated in Model A in Fig. 6 a. Increasing the ratio of HSPG:FGFR from the experimentally measured value for bone cells at (8.7:1) (67) increased the predicted proliferative response. Similarly, lowering the ratio decreased the predicted proliferative response. This effect was also observed in Models B and C*, but was not as pronounced in Model C* since all of the FGFRs are assumed to be constitutively bound to HSPGs before exposure to FGF2.

Subtle changes in heparan sulfate structure can have a dramatic effect on biological activity (94). Specific FGF2 induced changes have been observed in the molecular structure of heparan sulfate expressed on corneal endothelial cells (95) and arterial smooth muscle cells (96). Cell density has also been shown to impact HSPG expression, thus affecting FGF2 induced corneal stromal fibroblast mitogenic response (97). Human bone cells are also known to express different types of glycosaminoglycan chains on the same proteoglycan core protein (98). HS saccharides can play both an activating and inhibitory role in FGF2 binding to FGFRs by controlling the type of saccharide motifs expressed on HS chains (99). Such changes in HS structure or expression can influence the number of HSPGs capable of participating in FGF2-induced response and potential alterations in cell response are highlighted in Fig. 6 a.

The number of FGFRs on the cell surface also affected predicted proliferative response. As receptor dimerization is critical in FGF2 proliferative response, increases and decreases in FGFRs increased and decreased growth predictions in all models. The results for Model A are shown as an example in Fig. 6 b; the effect was similar in all models.

Additional observations on proliferation predictions

The effect of cell density on proliferative response was evaluated over a series of concentrations. Similar effects were seen in all models. At concentrations of 106–108 cells/L, proliferative response was similar. At highly dense concentrations (109–1010 cells/L), there is an obvious shift in the predicted proliferative response curve and decreased response at several concentrations of FGF2. This is not unexpected, since ligand depletion at this cell density would decrease ligand availability for signaling complex formation. This effect was similar in all models; Model B is shown as an example in Fig. 6 c. Another salient feature of proliferative signaling illustrated in Fig. 6 c is the concept of thresholding (100). By multiplying the molar FGF2 concentration at each evaluated dose by Avogadro's number divided by the cell density (Nav/ρ), we can approximate the number of ligand molecules available per cell. Although the model predicts large-scale increases in cell growth starting before 0.1 ng/ml for cell densities between 106 and 108 cells/L, such growth does not begin to occur at densities of 109 and 1010 cells/L until 0.1 and 1 ng/ml, respectively. For these cell densities and ligand concentrations, this corresponds to ∼3000 molecules of FGF2 available per cell. While this threshold provides an explanation for the results observed mathematically, its relevance in vitro would have to be explored experimentally. Richardson and colleagues found FGF2 induced rabbit stromal fibroblasts cell proliferation to be cell density-dependent, with maximum cell proliferation found at intermediate cell densities (97). They found a reduction in FGF2 binding per cell as cell density increased. This density-dependent binding reduction was found not to be a function of reduced FGFR expression but rather modulation of heparan sulfate proteoglycan expression (HSPGs). If HSPGs act as regulators of FGF2 bioavailability (101), it is plausible that the concept of thresholding in this system may not only be a function of ligand concentration per cell in surrounding media, but also the local binding environment in which the allosteric interaction of HSPGs with FGFR control the availability of FGF2 per cell.

Internal processing and media release of FGF2 and HSPG

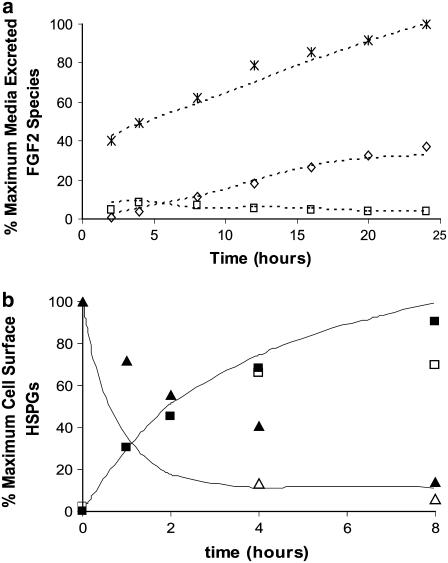

Initial calculations for the intracellular fate of FGF2 indicated that the linear rate constants obtained from the literature alone were not sufficient to describe the experimentally observed intracellular phenomenon at 0.28 nM FGF2 (76). Since a considerable portion of the intracellular FGF2 was bound to HSPG in the model (CsHF), we evaluated the metabolism of HSPGs to find clues to potentially resolve the discrepancies between the predicted data and the experimental data.

The cell surface HSPGs on rat ovarian granulosa cells are either lost into the medium (30%, t1/2 = 4 h) or internalized (70%, t1/2 = 4 h). HSPGs that are internalized either migrate to lysosomes where they are rapidly degraded without forming intermediate products (60%, t1/2 = 30 min) or enter into a longer processing pathway including proteolysis and endoglycosidic degradation to one-third their original size in endosomes (t1/2 = 30 min), followed by endoglycosidic degradation in lysosomes of one-quarter to one-fifth their original size (t1/2 = 30–60 min), and then after a long half-life (t1/2 = 3–4 h), are rapidly degraded in lysosomes (74). Similarly, medium secretion and two post-internalization catabolic pathways have been observed for HSPGs on Chinese Hamster Ovarian (CHO) cells and the distribution of both cell and medium associated HSPGs were similar when cells were exposed to 5 ng/ml (0.25 nM) FGF2 (77). In the CHO cell study, the authors suggested that FGF2 remains in complex with HSPGs and is transported through the same endosomal pathway.

Since all CsT values are assumed to be internalized, the possibility of a nonlinear, multistep process describing the internalization of surface HSPG-FGF2 complexes (CsHF) was investigated. The internalization rate for CsHF (kiCHF) was multiplied by various step functions in an attempt to fit experimental data. The function I(t) (Table 3) was in good agreement with experimental values of intracellular 18–16 kDa FGF2 (Fig. 7). However, the model underpredicted the value of media excreted products at the early time points but was successful at later time points (data not shown). Examination of these results suggested the possibility of an early burst or release of CsHF into the surrounding media at the relatively high, nonphysiologic concentration at which the experiment was preformed (0.28 nM FGF2). Such a release could follow the normal HSPG metabolism described above. Various step functions were tested in the model to account for this release from the cell surface and R(t) (Table 3) was found to fit the data. As illustrated in the experimentally determined pathway for HSPG metabolism in granulose cells, there are likely multiple steps involved in the processing of HSPGs and FGF2-bound HSPGs. This was evident in the lack of correlation to experimental data after inclusion of the surface release step function R(t). Subsequently, the use of step functions to accommodate potential multistep processes in the internalization of surface species and the formation of LMW fragments were evaluated. All of the FGF2 transported to the nucleus was assumed to be shuttled from ternary complex fractions (fCT) opposed to FGF2/HSPG complexes (fCHF). FGFRs are required for the exogenous FGF2 stimulation of proliferation. Therefore, it is assumed that complexes without FGFRs would not contribute to FGF2 induced mitogenic signaling. All of the models used the same equations to represent the internal processing of FGF2 (Table 3) and predicted similar results. Model A is used as a representative in Fig. 7 a.

FIGURE 7.

(a) Prediction of the intracellular processing of FGF2 for Model A. Model predictions (dotted line) are compared to experimentally measured results from VSMCs exposed to 0.28 nM FGF2 (76). Experimental results are compared to their model counterparts and include intracellular 18–16 kDa FGF2 (□) (compared to CiHF + CiT), intracellular low molecular weight FGF2 (⋄) (compared to CLMW), and media excreted products (*) (compared to Cm) are presented as a percentage of the maximum of FGF2 excreted products. The step functions I(t), L(t), and R(t) were used to compensate for differences observed in model predicted Hs and CsHF internalization and release into surrounding medium as well as LMW fragment formation. The results are similar in all Models A–C*. (b) Prediction of the metabolic processing of HSPGs for Model A. Model predictions (solid line) are compared to experimentally measured results from rat ovarian granulose cells (74) detailing HSPG cell surface concentration (▴) (compared to Hs + CsHF + CsHR + CsI + CsT) and HSPG accumulation in the media (▪) (compared to Hm + Cm) determined during 80 min pulse-chase experiments. Results are also compared to HSPG metabolism in Chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cells exposed to 5 ng/ml FGF2 as determined by 1 h pulse-chase experiments (77) (HSPG cell surface concentration (▵) and HSPG accumulation in the media (□)). The results are similar in all Models A–C*.

While there was a good fit between the experimental data and model predicted results for the fate of intracellular ligand, it was highly dependent upon the inclusion of the step functions I(t), L(t), and R(t), indicating the potential relevance of the involvement of multiple steps in the internalization, LMW fragment formation, and medium release of exogenously added FGF2 at relatively high doses (0.28 nM). It must be noted that since the only kinetic and experimental data available in the literature was performed on VSMCs, direct correlations to osteoblastic cells could not be drawn. Differences in FGFR and HSPG expression could potentially correlate to differences in osteoblastic response. Distinct kinetic differences in the metabolism of various HSPGs (102) could also alter the relevance of the step functions applied in this model.

Fig. 7 b shows data for media release and cell surface presence of HSPGs. Model predictions are compared to experimentally measured results from rat ovarian granulose cells (74) during 80 min pulse-chase experiments and Chinese hamster ovarian (CHO) cells exposed to 5 ng/ml FGF2 as determined by 1 h pulse-chase experiments (77). Experimental data for osteoblasts was not available in the literature. However, it is evident in Fig. 7 b that the model predictions follow the pattern of response of HSPG metabolism in two types of mesenchymal cells. Similarities in the response of the granulose (not exposed to FGF2) and CHO cells (exposed to FGF2) are evident. This is consistent with similarities between the metabolic patterns observed in CHO cells both with and without exposure to 5 ng/ml FGF2 and provides evidence that HSPG metabolism is not altered at relatively high concentrations of FGF2 (77). These experimental results establish a framework through which both the processing of HSPG- and FGFR-bound FGF2 can be theoretically evaluated and has tremendous implications on the bioavailability of growth factors through regulation by HSPGs. Utilizing this framework of HSPG involvement in FGF2 bioavailability in our model is supported by in vivo evidence of HSPGs clearing exogenously added FGF2 in Sprague-Dawley rats through cellular internalization and catabolism without inducing the activation of FGFRs within at least five organs in vivo (101). Finally, sustained presence of a fraction of LMW FGF2 fragments observed within several types of mesenchymal cells (80,81,103) could then be accounted for by the normal metabolic processing of HSPGs (74).

Relevance of other proliferative signaling complex stoichiometries

While these models provide some insight into the potential mechanisms of FGF2 induced proliferative signal complex formation, it is important to continue this evaluation with respect to the other potential stoichiometric configurations that involve FGFR dimerization. Although substantial information has been gained about the potential architecture of the signaling complexes isolated using crystallographic methods, neither configuration was solved in a true physiological state in which the heparan sulfate chains on the proteoglycans involved are longer and receptors are bound to the cell membrane (49). Accordingly, the physiological relevance of the 2:2:2 (47) and 2:1:2 (48) models cannot be confirmed or excluded with certainty. A similar argument holds for the alternate 1:1:2 model, solved using biophysical analysis (50). While FGF2 dimers are linked to the proliferative signaling complex (104,105), the identification of two receptor binding surfaces on FGF2 (106) presents the possibility that under certain circumstances, FGFR dimerization could occur without FGF2 dimerization. We will examine binding pathways leading to both a 2:1:2 and 1:1:2 proliferative signaling complex in future work.

CONCLUSION

Using available rate constants from literature, this model suggests that the piecewise assemblage of a 2:2:2 FGF2:HSPG:FGFR proliferative complex can occur in multiple ways, and thus may be dependent upon the local environment surrounding FGF2 binding. This environment is characterized by cell type, density, maturation, and the type and expression of FGFRs and HSPGs on a given cell surface. It also suggests that at relatively high concentrations of exogenous FGF2 (0.28 nM), there may be multistep processes involved in the medium release, internalization, and LMW fragment formation of HSPGs and FGF2-bound HSPGs. This model also supports the notion of HSPG involvement in the bioavailability of FGF2 through their metabolic processing, which likely also accounts for the long half-life observed with internalized FGF2. Experimental measurements of the model estimated rate constants will have to be made to determine the relevance of these predictions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health training grant No. AR07132, the National Science Foundation grants No. 0115404 and BES-0343620, and partially supported by funds to the Wistar Institute from the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program-Pennsylvania Department of Health and the Laboratory Research Fund of S. R. Pollack.

References

- 1.Muraglia, A., R. Cancedda, and R. Quarto. 2000. Clonal mesenchymal progenitors from human bone marrow differentiate in vitro according to a hierarchical model. J. Cell Sci. 113:1161–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruder, S. P., N. Jaiswal, and S. E. Haynesworth. 1997. Growth kinetics, self-renewal, and the osteogenic potential of purified human mesenchymal stem cells during extensive subcultivation and following cryopreservation. J. Cell. Biochem. 64:278–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banfi, A., A. Muraglia, B. Dozin, M. Mastrogiacomo, R. Cancedda, and R. Quarto. 2000. Proliferation kinetics and differentiation potential of ex vivo expanded human bone marrow stromal cells: implications for their use in cell therapy. Exp. Hematol. 28:707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Knoch, F., C. Jaquiery, M. Kowalsky, S. Schaeren, C. Alabre, I. Martin, H. E. Rubash, and A. S. Shanbhag. 2005. Effects of bisphosphonates on proliferation and osteoblast differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 26:6941–6949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gori, F., T. Thomas, K. C. Hicok, T. C. Spelsberg, and B. L. Riggs. 1999. Differentiation of human marrow stromal precursor cells: bone morphogenetic protein-2 increases OSF2/CBFA1, enhances osteoblast commitment, and inhibits late adipocyte maturation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 14:1522–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu, P., B. O. Oyajobi, R. G. G. Russell, and A. Scutt. 1999. Regulation of osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells: interaction between transforming growth factor-β and 1,25(OH)(2) vitamin D-3 in vitro. Calcif. Tissue Int. 65:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin, I., A. Muraglia, G. Campanile, R. Cancedda, and R. Quarto. 1997. Fibroblast growth factor-2 supports ex vivo expansion and maintenance of osteogenic precursors from human bone marrow. Endocrinology. 138:4456–4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bianchi, G., A. Banfi, M. Mastrogiacomo, R. Notaro, L. Luzzatto, R. Cancedda, and R. Quarto. 2003. Ex vivo enrichment of mesenchymal cell progenitors by fibroblast growth factor 2. Exp. Cell Res. 287:98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bikfalvi, A., S. Klein, G. Pintucci, and D. B. Rifkin. 1997. Biological roles of fibroblast growth factor-2. Endocr. Rev. 18:26–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gospodarowicz, D., N. Ferrara, L. Schweigerer, and G. Neufeld. 1987. Structural characterization and biological functions of fibroblast growth-factor. Endocr. Rev. 8:95–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fannon, M., K. E. Forsten, and M. A. Nugent. 2000. Potentiation and inhibition of bFGF binding by heparin: a model for regulation of cellular response. Biochemistry. 39:1434–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowd, C. J., C. L. Cooney, and M. A. Nugent. 1999. Heparan-sulfate mediates bFGF transport through basement membrane by diffusion with rapid reversible binding. J. Biol. Chem. 274:5236–5244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsten, K. E., M. Fannon, and M. A. Nugent. 2000. Potential mechanisms for the regulation of growth factor binding by heparin. J. Theor. Biol. 205:215–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Padera, R., G. Venkataraman, D. Berry, R. Godavarti, and R. Sasisekharan. 1999. FGF-2/fibroblast growth factor receptor/heparin-like glycosaminoglycan interactions: a compensation model for FGF-2 signaling. FASEB J. 13:1677–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filion, R. J., and A. S. Popel. 2004. A reaction-diffusion model of basic fibroblast growth factor interactions with cell surface receptors. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 32:645–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopalakrishnan, M., K. Forsten-Williams, and U. C. Tauber. 2004. Ligand-induced coupling versus receptor pre-association: cellular automaton simulations of FGF-2 binding. J. Theor. Biol. 227:239–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibrahimi, O. A., F. M. Zhang, S. C. L. Hrstka, M. Mohammadi, and R. J. Linhardt. 2004. Kinetic model for FGF, FGFR, and proteoglycan signal transduction complex assembly. Biochemistry. 43:4724–4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forsten-Williams, K., C. C. Chua, and M. A. Nugent. 2005. The kinetics of FGF-2 binding to heparan-sulfate proteoglycans and MAP kinase signaling. J. Theor. Biol. 233:483–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaye, M., J. Schlessinger, and C. A. Dionne. 1992. Fibroblast growth-factor receptor tyrosine kinases—molecular analysis and signal transduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1135:185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keresztes, M., and J. Boonstra. 1999. Import(ance) of growth factors in(to) the nucleus. J. Cell Biol. 145:421–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Florkiewicz, R. Z., A. Baird, and A. M. Gonzalez. 1991. Multiple forms of bFGF: differential nuclear and cell surface localization. Growth Factors. 4:265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arnaud, E., C. Touriol, C. Boutonnet, M. C. Gensac, S. Vagner, H. Prats, and A. C. Prats. 1999. A new 34-kiloDalton isoform of human fibroblast growth factor 2 is cap-dependently synthesized by using a non-AUG start codon and behaves as a survival factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:505–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rifkin, D. B., N. Quarto, P. Mignatti, J. Bizik, and D. Moscatelli. 1991. New observations on the intracellular-localization and release of BFGF. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 638:204–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delrieu, I. 2000. The high molecular weight isoforms of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2): an insight into an intracrine mechanism. FEBS Lett. 468:6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powers, C. J., S. W. McLeskey, and A. Wellstein. 2000. Fibroblast growth factors, their receptors and signaling. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 7:165–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sleeman, M., J. Fraser, M. McDonald, S. N. Yuan, D. White, P. Grandison, K. Kumble, J. D. Watson, and J. G. Murison. 2001. Identification of a new fibroblast growth factor receptor, FGFR5. Gene. 271:171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krufka, A., S. Guimond, and A. C. Rapraeger. 1996. Two hierarchies of FGF-2 signaling in heparin: mitogenic stimulation and high-affinity binding/receptor transphosphorylation. Biochemistry. 35:11131–11141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delehedde, M., M. Seve, N. Sergeant, I. Wartelle, M. Lyon, P. S. Rudland, and D. G. Fernig. 2000. Fibroblast growth factor-2 stimulation of p42/44(MAPK) phosphorylation and IκB degradation is regulated by heparan-sulfate/heparin in rat mammary fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 275:33905–33910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yayon, A., M. Klagsbrun, J. D. Esko, P. Leder, and D. M. Ornitz. 1991. Cell-surface, heparin-like molecules are required for binding of basic fibroblast growth-factor to its high-affinity receptor. Cell. 64:841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fannon, M., and M. A. Nugent. 1996. Basic fibroblast growth factor binds its receptors, is internalized, and stimulates DNA synthesis in Balb/c3T3 cells in the absence of heparan-sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 271:17949–17956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dailey, L., D. Ambrosetti, A. Mansukhani, and C. Basilico. 2005. Mechanisms underlying differential responses to FGF signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 16:233–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klint, P., and L. Claesson-Welsh. 1999. Signal transduction by fibroblast growth factor receptors. Front. Biosci. 4:D165–D177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pages, G., P. Lenormand, G. Lallemain, J. C. Chambard, S. Meloche, and J. Pouyssegur. 1993. Mitogen-activated protein-kinases P42(MAPK) and P44(MAPK) are required for fibroblast proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90:8319–8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson, G. L., and R. Lapadat. 2002. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 298:1911–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlessinger, J. 2000. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 103:211–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kudla, A. J., N. C. Jones, R. S. Rosenthal, K. Arthur, K. L. Clase, and B. B. Olwin. 1998. The FGF receptor-1 tyrosine kinase domain regulates myogenesis but is not sufficient to stimulate proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 142:241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouche, G., N. Gas, H. Prats, V. Baldin, J. P. Tauber, J. Teissie, and F. Amalric. 1987. Basic fibroblast growth-factor enters the nucleolus and stimulates the transcription of ribosomal genes in ABAE cells undergoing G0-G1 transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:6770–6774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailly, K., F. Soulet, D. Leroy, F. Amalric, and G. Bouche. 2000. Uncoupling of cell proliferation and differentiation activities of basic fibroblast growth factor. FASEB J. 14:333–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bossard, C., H. Laurell, L. Van den Berghe, S. Meunier, C. Zanibellato, and H. Prats. 2003. Translokin is an intracellular mediator of FGF-2 trafficking. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis, M. G., M. Zhou, S. Ali, J. D. Coffin, T. Doetschman, and G. W. Dorn. 1997. Intracrine and autocrine effects of basic fibroblast growth factor in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 29:1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maher, P. A. 1996. Nuclear translocation of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors in response to FGF-2. J. Cell Biol. 134:529–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kilkenny, D. M., and D. J. Hill. 1996. Perinuclear localization of an intracellular binding protein related to the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor 1 is temporally associated with the nuclear trafficking of FGF-2 in proliferating epiphyseal growth plate chondrocytes. Endocrinology. 137:5078–5089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benavente, C. A., W. D. Sierralta, P. A. Conget, and J. J. Minguell. 2003. Subcellular distribution and mitogenic effect of basic fibroblast growth factor in mesenchymal uncommitted stem cells. Growth Factors. 21:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reilly, J. F., and P. A. Maher. 2001. Importin β-mediated nuclear import of fibroblast growth factor receptor: role in cell proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 152:1307–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsia, E., T. P. Richardson, and M. A. Nugent. 2003. Nuclear localization of basic fibroblast growth factor is mediated by heparan-sulfate proteoglycans through protein kinase C signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 88:1214–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amalric, F., G. Bouche, H. Bonnet, P. Brethenou, A. M. Roman, I. Truchet, and N. Quarto. 1994. Fibroblast growth factor-II (FGF-2) in the nucleus—translocation process and targets. Biochem. Pharmacol. 47:111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlessinger, J., A. N. Plotnikov, O. A. Ibrahimi, A. V. Eliseenkova, B. K. Yeh, A. Yayon, R. J. Linhardt, and M. Mohammadi. 2000. Crystal structure of a ternary FGF-FGFR-heparin complex reveals a dual role for heparin in FGFR binding and dimerization. Mol. Cell. 6:743–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]