Abstract

Objective

This prospective blinded comparison of helical CT and helical CT arterial portography aimed to detect liver metastasis from colorectal carcinoma.

Subject & Methods

50 patients with colorectal carcinoma were evaluated comparing helical CT with helical CT arterial portography. Each imaging study was evaluated on a 5-point ROC scale by radiologists blinded to the other imaging findings and the results were compared with the surgical and pathologic findings as the gold standard.

Results

Of the 127 lesions found at pathology identified as metastatic colorectal cancer, helical CT correctly identified 85 (69%) and CT portography 96 (76%). When subgroups with lesions <3 cm (48 patients) and patients with maximum tumor size < 3 cm (18 patients) were considered, CT portography was always better than helical CT in terms of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value. ROC analysis adjusting for multiple lesions per patient revealed significantly greater area under the curve for the subgroup of lesions < 3 cm (CT-AUC of 77% and CT portography AUC of 81%; p=0.002).

Conclusion

For identification of large metastases, helical CT and CT portography have similar yield. However, for detection of small liver metastases, CT portography remains superior for lesion detectability.

Introduction

The liver is the most common site for hematogenous spread of colorectal carcinoma. In many cases, this organ is the sole site of metastases1. Over the last two decades, great strides have been made in surgical treatment of colorectal metastases isolated to the liver and both long-term survival as well as cure may now be routinely accomplished. In multiple large series with long-term followup, five year survival after such hepatic resection is on the order of 35–40% and ten year survival on the order of 20–25%2–4. The safety of such resections have greatly improved with operative mortality (even for resection of up to 80% of the liver) of less than 5%2–4. The improvements in safety and long-term outcome for liver resection have resulted in part from major improvements in the cross sectional imaging that directs the surgical therapy. CT arterial portography has been regarded as the most sensitive technique for determining which patients are optimal candidates for surgical resection5. This technique, however, is invasive, relatively expensive and in some instances may be less specific than other imaging techniques. Helical CT has become widely available allowing rapid volumetric acquisition of the entire liver in a single breath-hold6. The greater sensitivity of helical compared with conventional CT suggests that this technique may be a viable, less invasive alternative to CT arterial portography. The current study compares these two techniques in 50 consecutive patients who had resection of their hepatic colorectal metastases using pathological findings as the gold standard. This study seeks to determine if helical CT may be an adequate replacement for CT arterial portography. In addition, this study seeks to determine if there are subsets of patients for whom CT arterial portography would still be the preferred imaging modality.

Materials and Methods

Between April 1, 1999 and April 1, 2001, a prospective study was performed comparing helical CT and CT arterial portography (CTAP) in the preoperative detection of liver metastasis. This study was approved and performed under the auspices of the Institutional Review Board. Eighty-seven consecutive patients sent to a multidisciplinary liver team for evaluation of suspected liver metastases from colorectal carcinoma agreed to the study and underwent both imaging tests. All patients were imaged at a single institution in order to control for scanning technique and image quality. The purpose of the study was to evaluate and compare the results of both examinations in the preoperative staging of liver metastases. Patients were not excluded from either imaging study on the basis of findings on other imaging examinations.

Patient Characteristics

Eighty-seven patients were consented and enrolled in this study. Thirty-seven patients were not resected and therefore pathologic confirmation of surgical findings was not obtained. Therefore, they were excluded from the final analysis. These included 12 patients who were excluded from surgery because preoperative imaging disclosed extensive bilobar metastatic disease (n = 3) or extrahepatic disease (n = 9). In 25 cases, only bimanual surgical palpation and intraoperative sonography were performed because peritoneal spread of the tumor was detected at laparotomy. Imaging results in the remaining 50 patients was correlated with surgical and pathologic findings; these patients made up our final study group. This study group included 21 men and 29 women with an average age of 59. Six of the fifty patients had prior surgical resection and were found to have tumor recurrence, necessitating further hepatic resection.

Surgical procedures consisted of partial hepatectomy in 50 cases: (9 trisegmentectomies, 18 lobectomies, 22 segmentectomies, 1 non-anatomic wedge resections). The primary tumor originated in the colon in 39 cases and in the rectum in the remaining 11 cases.

Hepatic metastases were synchronous with the initial diagnosis of colonic cancer in 20 cases and metachronous in 30 cases. The interval between surgical resection of the primary tumor and detection of liver metastases ranged from 0 to 64 months (median: 5 months). Increased levels (>5 ng/ml) of carcinoembryonic antigen were detected in 35 patients (70%), with values ranging from 1 to 1272 ng/ml (median: 16.9 ng/ml).

Imaging Modalities

Helical CT

Helical CT was performed with GE Lightspeed (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) scanners capable of high resolution, wide dynamic range and rapid scanning. 600 – 800 ml of oral contrast was administered 45 to 60 minutes before scanning, with the last cup ingested 10 minutes before scan time. Imaging of the liver was performed with 5-mm collimation and a 1:1.5 pitch and was subsequently reconstructed at 5-mm intervals. Omnipaque (Amersham Health Inc., Princeton, NJ) was injected at a rate of 2.5 ml/sec (160 ml total) using an MCT power injector (MedRad, Pittsburgh, PA). The helical breath-hold acquisition was started 60–70 seconds following initiation of scanning. Evaluation was performed from the lung bases to the pubic symphysis.

CT Portography

CT Portography was performed immediately following SMA and celiac angiography. A selective catheter was placed in the proximal position of the SMA. In the case of accessory or replaced hepatic vessels arising from the SMA, a selective catheter was placed more distally, usually just proximal or into the ileocolic branch. For the portogram, non-ionic contrast was injected at 3 cc/sec for a total volume of 180 to 190 cc. A 60 to 63 second delay was utilized between start of injection and the image acquisition. 7mm contiguous axial images are acquired in a helical fashion (pitch =1.0), from the top of the liver through the bottom of the liver. After an additional 20 to 30 second delay, 10mm thick images are acquired helically in the reverse direction. The patient returned 4 hours later for follow-up scanning without additional contrast. 10mm thick images are obtained helically (pitch = 1.0) in a craniocaudad direction. Each set of helical images was obtained during a single breath-hold.

Image Review

Two radiologists, each with greater than 5 years experience in hepatobiliary imaging, prospectively assessed how well both imaging techniques revealed metastatic involvement of the liver and other abdominal and pelvic organs. The helical CT scans were interpreted in a blinded fashion by a single radiologist (L.S.) and the CTAP scans were read by a single interventional radiologist (L.B.) blinded to the results of the other scans. In all cases, the radiologist knew that the patient had colorectal carcinoma and suspected liver metastases but was unaware of the results of the other diagnostic procedure. The number, size, and location (according to the Couinaud numbering system) of each focal hepatic lesion were noted. Additional extra-hepatic foci of suspected metastatic disease was also noted on a standardized data form. On helical CT, lesions were considered metastatic if they were irregular low-attenuation lesions without characteristic findings of benign lesions (cysts or hemangiomas). Cysts were defined as water-density lesions with imperceptible walls and no contrast enhancement. Hemangiomas were defined as hypodense lesions with discontinuous peripheral nodular contrast enhancement. On CTAP, hypodense, round, well-defined space-occupying lesions were considered metastatic. Wedge-shaped perfusion defects peripherally located or in characteristic anatomic locations (segment IV or V, adjacent to the gallbladder or round ligament) were considered benign7.

A level of confidence that lesions seen were cancerous was graded by the reader on a five-point scale: 0-not cancerous; 1-unlikely to be cancer; 2-equivocal; 3 possibly cancer; 4-definitely cancer. The results were then compared with pathologic findings on a lesion-by-lesion basis.

All surgical liver procedures were performed by one of four experienced hepatic surgeons. During operation, the liver was carefully examined both by palpation and by intraoperative sonography to confirm the number and size of the metastases, and to define their relationship with vascular landmarks. The hepatic surgeon was aware of the results of both helical CT and CTAP and performed intraoperative sonography with a flexible system, SSD-1100 (Aloka, Tokyo, Japan), using a 5-and 7.5-MHz intraoperative probe.

The mean interval between helical CT and surgery was 21 days (range 1–55 days). The mean interval between CTAP and surgery was 16 days (range 4–47 days). The mean interval between helical CT and CTAP was 8 days (range 1–33 days).

Pathology

Pathologic specimens were obtained with 5-mm slice intervals, and subsequent direct radiologic-pathologic correlation was performed. Each detected lesion was measured and examined microscopically. The results of this radiologic-pathologic correlation and those of the surgical palpation and intraoperative sonographic examination of non-resected portions of the liver constituted the gold standard of reference for this study. The findings at pathologic examination were compared with the results of both imaging techniques and recorded on the data sheet. Each lesion was confirmed to be cancerous by histologic examination. Lesions that were thought to be non-cancerous, such as liver cysts or perfusion artifacts, were confirmed at pathology.

Statistical Analyses

Two by five matrices of disease status at pathology (Disease positive (D+) versus Disease negative (D−)) versus CT and CT Portography score using a 5-point ROC scale were examined to assess the characteristics of these two modalities in terms of sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV). The calculations were tabulated by varying the cutpoint used to determine which value of the observed variable will be considered abnormal.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were fitted assuming underlying distribution to be bi-normal (using code ‘ROCFIT.exe’ developed by Dr. C.E. Metz at University of Chicago) and plotting the estimated sensitivities against the corresponding false positive rates. The overall index of accuracy for each modality is estimated by the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and the nonparametric comparison of the two ROC curves was made according to Obuchowski et al adjusting for multiple lesions per patient and the fact that the data is paired8. ROC analysis was repeated for different subgroups of size (< 3cm and maximum lesion size < 3 cm) to explore the possibility that comparative accuracy of the two modalities could be different for the subgroups.

Results

In the 50 patients examined, 127 lesions were found positive at pathology. The average number of lesions per patient is 5 with a range of 1–13. The size of the metastases ranged from 0.5 cm to 15 cm (mean of 2.1 cm and median of 1.35 cm). Both suspected benign and malignant lesions were identified at surgery and pathology.

Table 1A–D illustrates the sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV and NPV for CT and CTAP using a cutoff value of 0 and 1 for benign and 2 through 4 for malignant as well as 0, 1, 2 for benign and 3 and 4 for malignant.

Table 1A–D.

Matrices describing the characteristics of CT and CT Portography

| A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT ROC SCORE | ||||||

| Disease State | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| D+ | 29 | 1 | 9 | 14 | 74 | 127 |

| D− | 66 | 13 | 38 | 17 | 8 | 142 |

| B | ||

|---|---|---|

| COMBINED CT SCORES | ||

| 0–1 / 2–4 | 0–2 / 3–4 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.76 | 0.69 |

| Specificity | 0.56 | 0.82 |

| Accuracy | 0.65 | 0.76 |

| PPV | 0.61 | 0.78 |

| NPV | 0.73 | 0.75 |

| C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAP ROC SCORE | ||||||

| Disease State | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| D+ | 22 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 89 | 127 |

| D− | 68 | 19 | 30 | 14 | 11 | 142 |

| D | ||

|---|---|---|

| COMBINED CTAP SCORES | ||

| 0–1 / 2–4 | 0–2 / 3–4 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.82 | 0.76 |

| Specificity | 0.61 | 0.82 |

| Accuracy | 0.71 | 0.79 |

| PPV | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| NPV | 0.79 | 0.79 |

D+ = Disease positive D− = Disease negative

Helical CT

Using a cutoff value of 0, 1, 2 for benign and 3 and 4 for malignant, helical CT detected 85 of 127 hepatic metastases for a sensitivity of 69%.

CTAP

Using a cutoff value of 0, 1, 2 for benign and 3 and 4 for malignant, CTAP detected 96 of 127 hepatic metastases for a sensitivity of 76%.

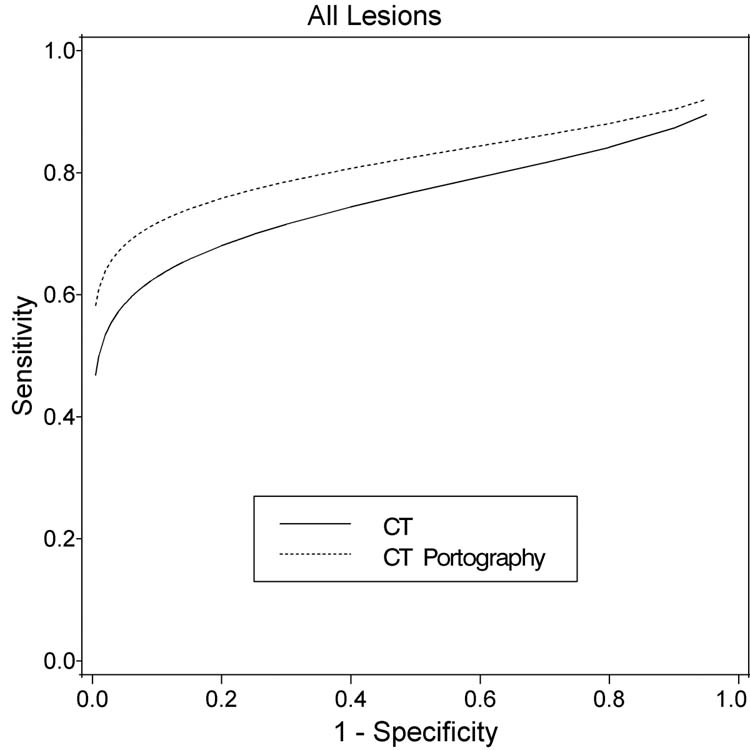

All lesions

Sensitivity for CT was 77%, 76%, 69%, and 58% compared to 83%, 82%, 76%, and 70%, respectively for varying the cutoff from 0 to 3 on the 5-point scale (Figure 1). However, when analyzed as paired data adjusting for multiple lesions, the accuracy in terms of area under the curve (AUC) for CT-AUC is 0.77 +/− 0.03 and for CT portography–AUC is 0.81 +/− 0.03 are not significantly different (p=0.19; Table 2). For CT, the sensitivity and specificity were 76% and 56% when the equivocal (category 2) lesions were considered malignant; when the category 2 were considered benign, the sensitivity fell to 69% while the specificity increased to 82%. The accuracy varied from 65% to 76% depending upon the classification of these equivocal lesions. In CTAP, the sensitivity and specificity were 82% and 61% and changed to 76% and 82% depending upon classification of the category 2 lesions.

Figure 1.

Fitted ROC curves for CT and CT-Portography for all patients (50 patients, 269 lesions); X-axis = False Positive Fraction (1 – Specificity); Y- axis = True Positive Fraction (Sensitivity).

Table 2.

Area under the curve comparison:

| Group | N (Patients) | N (Lesions at pathology) | N (Lesions by scan) | CT AUC (SE) | CT Port AUC (SE) | Diff. | p-value | CI on diff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All* | 50 | 127 | 269 | 0.77 (0.03) | 0.81 (0.03) | −0.04 | 0.19 | (−0.11, 0.02) |

| lesions <=3 | 48 | 89 | 226 | 0.56 (0.04) | 0.75 (0.04) | −0.19 | 0.002 | (−0.31, −0.07) |

| max lesion <=3 per pt | 18 | 49 | 108 | 0.77 (0.04) | 0.83 (0.03) | −0.06 | 0.18 | (−0.14, 0.03) |

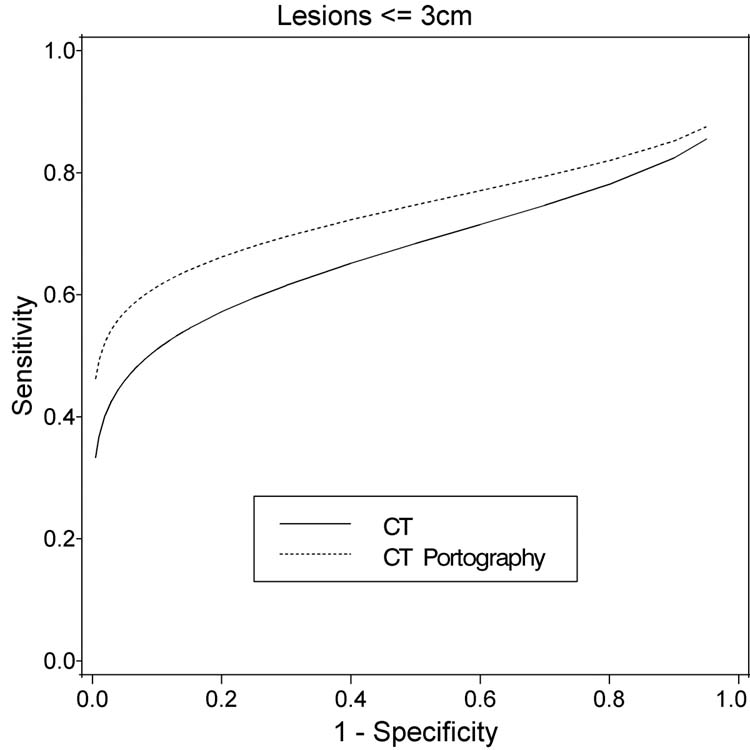

Small Lesions

When lesions < 3 cm in greatest diameter (48 patients) were considered, the accuracy of CT portography was significantly superior (CT-AUC: 0.56+/− 0.04 versus CT portography–AUC: 0.75+/− 0.03, p=0.002). There were 89 lesions < 3 cm confirmed to be cancer on pathologic analysis. Helical CT identified 52 of these lesions (using ROC 2 as the cutoff) with a sensitivity of 58% and a positive predictive value of 68%. CT portography detected 59 of these lesions with a sensitivity of 66% and a positive predictive value also of 76% (Table 3D and Figure 2).

Table 3A–D.

Matrices describing the characteristics of CT and CT Portography for Lesions <= 3 cm

| A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT ROC SCORE | ||||||

| Disease State | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| D+ | 28 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 40 | 89 |

| D− | 65 | 13 | 35 | 17 | 7 | 137 |

| B | ||

|---|---|---|

| COMBINED CT SCORES | ||

| 0–1 / 2–4 | 0–2 / 3–4 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.67 | 0.58 |

| Specificity | 0.57 | 0.83 |

| Accuracy | 0.61 | 0.73 |

| PPV | 0.50 | 0.68 |

| NPV | 0.73 | 0.75 |

| C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAP ROC SCORE | ||||||

| Disease State | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| D+ | 22 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 53 | 89 |

| D− | 63 | 19 | 30 | 14 | 11 | 137 |

| D | ||

|---|---|---|

| COMBINED CTAP SCORES | ||

| 0–1 / 2–4 | 0–2 / 3–4 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.74 | 0.66 |

| Specificity | 0.60 | 0.82 |

| Accuracy | 0.66 | 0.76 |

| PPV | 0.55 | 0.70 |

| NPV | 0.78 | 0.79 |

D+ = Disease positive D− = Disease negative

Figure 2.

Fitted ROC curves for CT and CT-Portography for lesion size <=3 cm (48 patients, 226 lesions)

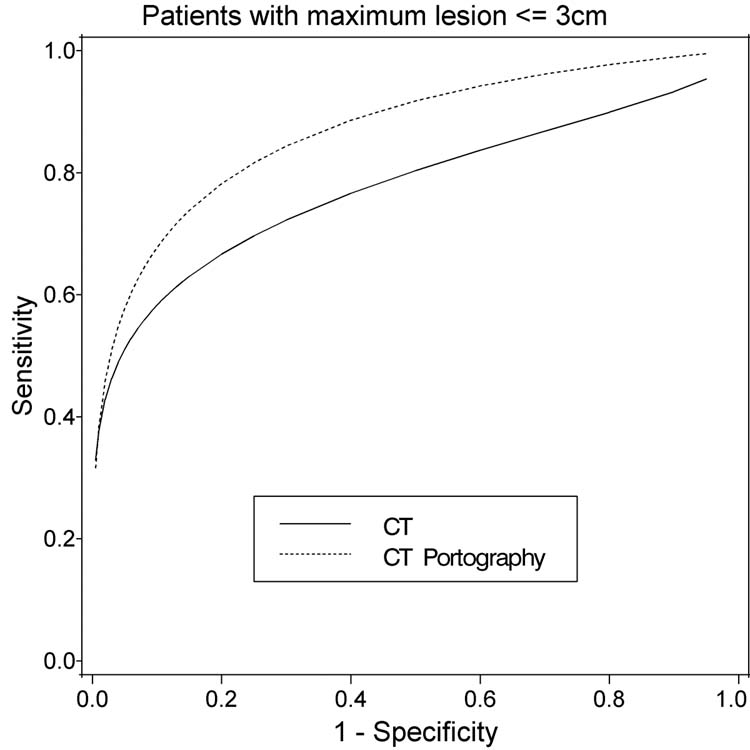

The trend of CT portography performing better than CT remains similar for subgroups of patients with maximum lesion size < 3 cm. However, there were only 18 patients in this analysis and the difference in accuracy of the two modalities were not significantly different (Table 4A–D and Figure 3).

Table 4A–D.

Matrices describing the characteristics of CT and CT Portography for patient with max lesion <= 3 cm

| A | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT ROC SCORE | ||||||

| Disease State | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| D+ | 8 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 26 | 49 |

| D− | 22 | 8 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 59 |

| B | ||

|---|---|---|

| COMBINED CT SCORES | ||

| 0–1 / 2–4 | 0–2 / 3–4 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.82 | 0.71 |

| Specificity | 0.51 | 0.75 |

| Accuracy | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| PPV | 0.58 | 0.70 |

| NPV | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| C | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTAP ROC SCORE | ||||||

| Disease State | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total |

| D+ | 4 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 37 | 49 |

| D− | 28 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 59 |

| D | ||

|---|---|---|

| COMBINED CTAP SCORES | ||

| 0–1 / 2–4 | 0–2 / 3–4 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| Specificity | 0.59 | 0.73 |

| Accuracy | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| PPV | 0.65 | 0.71 |

| NPV | 0.90 | 0.83 |

D+ = Disease positive D− = Disease negative

Figure 3.

Fitted ROC curves for CT and CT-Portography for greatest lesion size per person <=3 cm (18 patients, 108 lesions)

Clinical Significance

In eight patients, there was improved detection of subsequently documented liver metastases by CT portography compared with helical CT. In two of these, the additional lesions did not change the surgical procedure as the right lobectomy and right trisegmentectomy planned for these two cases encompassed the additional lesions. In the remaining six, the additional lesions dictated a change in planned resections. In three, the additional findings dictated a wedge resection contralateral to a lobectomy. In one, a caudate resection was performed in addition to a right lobectomy. In the remaining two, a right posterior sectorectomy was performed instead of a segment six resection. It is possible that these lesions would have been detected at surgery and surgical plans altered then. The only way to know how often the CT portography would have improved upon surgical exploration for detection of metastases is to blind the surgeon as to the CT portography findings until the surgical exploration had already been completed. We did not feel that study design to be ethical because of fear that patients with clearly unresectable disease by CT portography may be subjected to an unnecessary laparotomy. It is clear that detection of additional lesions by CT portography allows for surgical planning for complex resections for liver metastases.

Discussion

Data over the last two decades has demonstrated surgical treatment to be safe and effective for metastatic colorectal cancer. At major centers, resections are being performed with an operative mortality between 2–3% resulting in 5 year survival for patients at 30–50%2–4. A disease which 20 years ago was thought to be uniformly fatal within 12 months is now being treated with a possibility for cure. Much of the improvement in the surgical therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer has resulted from advancements in radiologic staging. CT portography is one of these innovations allowing sensitive detection of liver metastases for surgical planning9. Over the last decade, innovations in helical CT technology now allow another accurate and rapid method for evaluating patients with cancer10. This new scanning technique brings into question the need for the more invasive and costly CT portography. In the current study, we compare these two techniques in a prospective blinded fashion at a hepatobiliary tumor referral center to address this issue. The data demonstrates that with the imaging techniques employed in this study, CT portography remains more sensitive in detection of small lesions and is the test of choice for staging patients prior to surgical exploration.

Conventional CT has undergone significant changes in technology in the past few years. Helical CT is significantly faster than in the past and volumetric scanning may be done in a breath-hold6. More recently, enhanced helical CT with multi-detector capabilities has been developed which promises to enhance CT performance. Helical CT is the mainstay of imaging patients with colorectal cancer for both screening for metastases and staging patients for potential surgical resection11. The purpose of the current study was to determine if a standard helical CT is similar to CTAP for the detection of colorectal metastases to the liver. The advantage of helical CT is that it is obviously non-invasive.

One prior published report compared helical CT and CTAP and concluded that CT was superior (or at least equivalent) to CTAP in the detection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer12. The imaging methodology used in this previous paper was significantly different from our study’ principally in the utilization of non-helical CT acquisition for the CTAP examination. They also used different scanner manufacturers for the CT and CTAP. Finally, lesion selection differences between the two studies likely accounted in part for differences in sensitivity and specificity.

One of the limitations of CTAP has been a relatively high false positive rate. False positives are commonly seen at CTAP due to perfusion abnormalities. While the rate of false positives was higher with CTAP than CT in our study, it did not reach statistical significance. This is probably due to greater experience and confidence interpreting CTAP as well as the use of delayed scans with the acquisition of the complete CTAP study. A similar false positive rate was found with a helical CTAP paper5. There are a number of known causes of false positive findings on CTAP including focal fatty infiltration, regenerative nodules and other benign lesions5,7.

A rationale for the use of CTAP is not only a higher detection rate, but the ability to perform hepatic angiography to map the arterial vascular anatomy for the potential placement of hepatic arterial pumps and catheters. However, CT angiography and MR angiography is rapidly replacing conventional angiography in this role13–17.

Both CT and CTAP are limited in lesion characterization, therefore accounting for a relatively low specificity of both modalities. Certain lesion types are relatively characteristic on CTAP, including the wedge shaped perfusion defects, which are usually peripheral and almost always benign7. Rounded centrally located perfusion defects are seen both in benign and malignant processes. Similarly, CT provided only limited ability to characterize lesions such as cysts and hemangiomas.

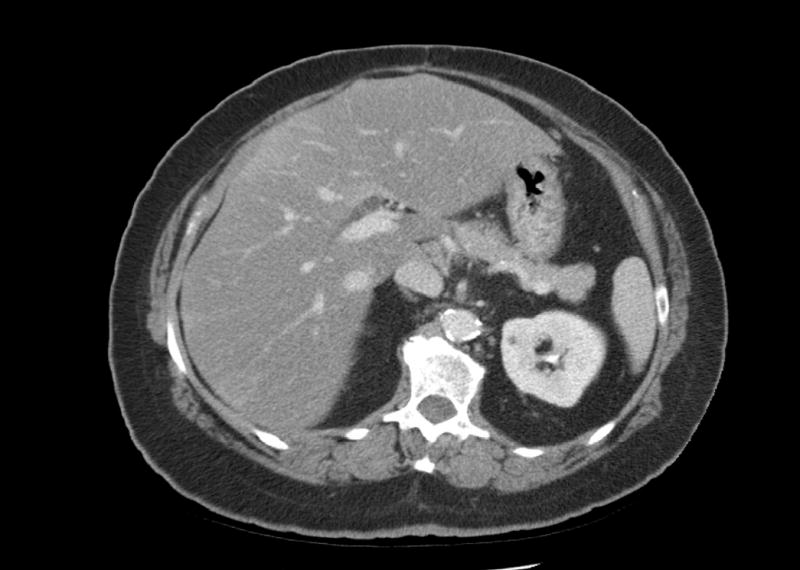

Our study used similar imaging protocols for both CT and CTAP, and concurred with earlier CTAP results demonstrating enhanced ability to visualize small lesions. In our study, CTAP had a sensitivity of 75% for these small lesions (Figure 4A and 4B). The identification of smaller lesions is not only important for surgical resection, but may also be important in the future use of ablative therapies for liver lesions. A number of ablative therapies, including cryoablation and radio frequency ablation are now being investigated and used for ablation of hepatic colorectal metastases18. These treatment modalities are much more effective in smaller lesions as there is a maximum area of ablation which may be achieved by any of these instruments. Finding smaller lesions may therefore allow use of these ablative therapies when they may indeed be not only palliative but curative as well. The size of lesions correlates with recurrence after ablation for obvious technical reasons. This raises the question of whether CT arterial portography should be considered prior to ablative therapy in these patients. A prospective study using CT arterial portography for staging prior to ablation with duration of response as an endpoint may address this question.

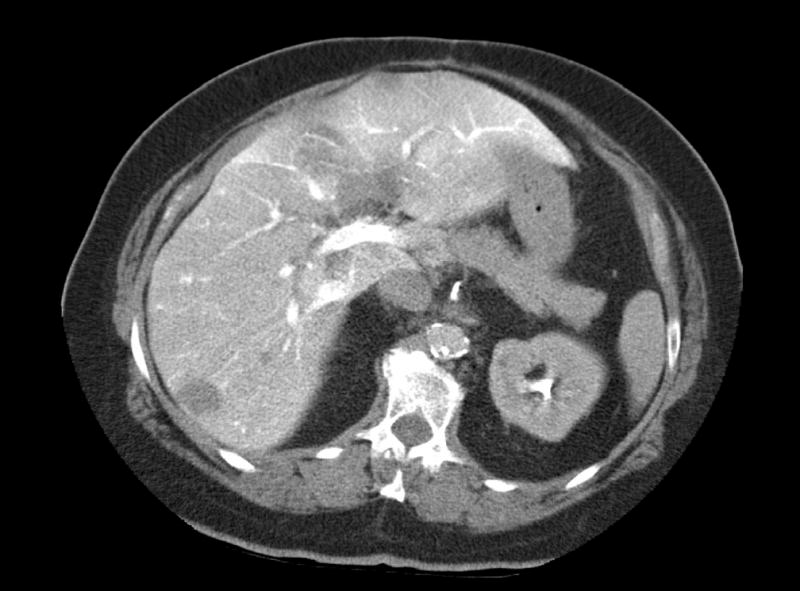

Figure 4A.

73 yo male with rising CEA. Helical CT did not definitively demonstrate tumor.

Figure 4B.

73 yo female demonstrated multiple tumors confirmed at surgery.

There are several limitations of our study. We utilized helical CT scanning technology rather than the newer multi detector technology19. Our study was started in 1999 prior to the introduction of the multi detector CT, and run in a prospective blinded fashion. Our results are still valid as multi detector CT is not universally available and a comparative imaging study which can only be accomplished by using standard protocols and technology until the study is complete. Another limitation is the lack of inclusion of other imaging modalities such as MRI. It was not the purpose to compare MRI in this study, though we anticipate follow up studies with other imaging modalities and in a multi-modality approach.

One issue that cannot be addressed by the current data is the cost-effectiveness of the increased sensitivity of CT arterial portography. Lesions visualized by helical CT that are more likely to be detected by CT portography are the smaller lesions. These are also the ones that are more likely to be missed at the time of surgery. Any missed lesions may lead to inappropriate use of a potentially morbid surgical procedure. Any missed lesions may also lead to the need for subsequent re-excision and with the morbidity and cost associated. We therefore feel that the most accurate test that allows for staging needs to be used prior to such resections. Our data demonstrates that CT portography with an imaging protocol as described is more sensitive for the detection of small hepatic metastases. In particular, CT portography should be considered in patients with multiple, small liver metastases. It should also be considered in the search for tumor in someone with a rising CEA and no visible lesions on conventional scanning.

Footnotes

Supported in part by grants RO1CA75416, RO1CA72632, and RO1CA61524 (Y.F.) from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Kemeny N, Fong Y. Treatment of liver metastases. In: Holland JF, Frei E, Bast RC et al, eds. Cancer Medicine 4 ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1997:1939–54.

- 2.Scheele J. Liver resection for colorectal metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00316981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de Chirurgie. Cancer. 1996;77:1254–1262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong Y, Fortner JG, Sun R, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–321. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soyer P, Levesque M, Elias D, Zeitoun G, Roche A. Preoperative assessment of resectability of hepatic metastases from colonic carcinoma: CT portography vs sonography and dynamic CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:741–744. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.4.1529835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeman RK, Fox SH, Silverman PM, et al. Helical (Spiral) Ct of the Abdomen. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:719–725. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.4.8456652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson MS, Baron RL, Dodd GD, III, et al. Hepatic parenchymal perfusion defects detected with CTAP: imaging- pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1992;185:149–155. doi: 10.1148/radiology.185.1.1326119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obuchowski NA. Nonparametric analysis of clustered ROC curve data. Biometrics. 1997;53:567–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soyer P, Bluemke DA, Hruban RH, Sitzmann JV, Fishman EK. Hepatic Metastases from Colorectal-Cancer - Detection and False-Positive Findings with Helical Ct During Arterial Portography. Radiology. 1994;193:71–74. doi: 10.1148/radiology.193.1.8090923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charny CK, Jarnagin WR, Schwartz LH, et al. Management of 155 patients with benign liver tumours. Br J Surg. 2001;88:808–813. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonaldi VM, Bret PM, Reinhold C, Atri M. Helical Ct of the Liver - Value of An Early Hepatic Arterial Phase. Radiology. 1995;197:357–363. doi: 10.1148/radiology.197.2.7480677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valls C, Lopez E, Guma A, et al. Helical CT versus CT arterial portography in the detection of hepatic metastasis of colorectal carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1341–1347. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.5.9574613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catalano C, Laghi A, Fraioli F, et al. High-resolution CT angiography of the abdomen. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:479–487. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahani D, Saini S, Pena C, et al. Using multidetector CT for preoperative vascular evaluation of liver neoplasms: technique and results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:53–59. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.1.1790053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sze DY, Razavi MK, So SK, Jeffrey RB., Jr Impact of multidetector CT hepatic arteriography on the planning of chemoembolization treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:1339–1345. doi: 10.2214/ajr.177.6.1771339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glockner JF. Three-dimensional gadolinium-enhanced MR angiography: applications for abdominal imaging. Radiographics. 2001;21:357–370. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr14357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choyke PL, Yim P, Marcos H, Ho VB, Mullick R, Summers RM. Hepatic MR angiography: a multiobserver comparison of visualization methods. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:465–470. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.2.1760465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Decadt B, Siriwardena AK. Radiofrequency ablation of liver tumours: systematic review. Lancet Oncology. 2004;5:550–560. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamel IR, Kruskal JB, Pomfret EA, Keogan MT, Warmbrand G, Raptopoulos V. Impact of multidetector CT on donor selection and surgical planning before living adult right lobe liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:193–200. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]