Abstract

Enterococcus faecalis is an important agent of endocarditis and urinary tract infections, which occur frequently in hospitals. Antimicrobial therapy is complicated by the emergence of drug-resistant strains, which contribute significantly to mortality associated with E. faecalis infection. In this issue of the JCI, Nallapareddy and colleagues report that E. faecalis produces pili on its surface and that these proteinaceous fibers are used for bacterial adherence to host tissues and for the establishment of biofilms and endocarditis (see the related article beginning on page 2799). This information may enable new vaccine strategies for the prevention of E. faecalis infections.

Enterococcus faecalis — snapshots of the pathogen

Enterococcus faecalis, a commensal bacterium of human biliary and gastrointestinal tracts, is a leading cause of surgical site, bloodstream, and urinary tract infections (1). Furthermore, E. faecalis is also a causal agent of bacterial endocarditis, whose complications — including congestive heart failure, septic emboli, and glomerulonephritis —result in mortality (2). Current management of enterococcal endocarditis involves administration of a combination of antimicrobials; however, the emergence of strains with multiple antibiotic resistance, including vancomycin resistance (e.g., vancomycin-resistant enterococci), present continuously increasing problems (3). Epidemiological studies show that more than 20% of enterococci isolated from infections of intensive care unit patients display vancomycin resistance (4). Thus, research that has the potential to unveil new therapies or preventive measures that disrupt the pathogenesis of enterococcal endocarditis is urgently needed.

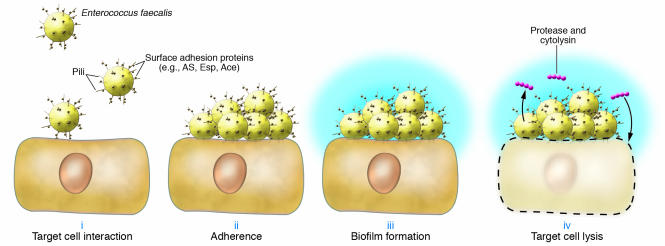

What makes E. faecalis a pathogen? Unlike group A streptococci or Staphylococcus aureus, which are virulent microbes that secrete a plethora of hemolysins and toxins to battle innate immune responses (5, 6), E. faecalis pathogenesis relies on fewer virulence factors (7). Two protein adhesins, enterococcal surface protein (Esp) and adhesion to collagen from E. faecalis (Ace), are thought to mediate enterococcal attachment to host tissues (8, 9), while aggregation substance (AS) promotes aggregation of replicating microbes (10). Enterococci regulate protease expression (a secreted virulence factor involved in tissue degradation) via the E. faecalis regulator (fsr) quorum-sensing locus, including fsrC sensory kinase, fsrA response regulator, and fsrB-derived autoinducer (11). Once an infectious nidus harbors threshold numbers of enterococci, Fsr signaling activates protease secretion (11). Esp, Ace, Fsr, and protease are involved in the formation of a biofilm, a surface-attached bacterial community enclosed in extracellular matrix where enterococci assume a slower growth rate, increased antibiotic resistance, and elevated frequency of lateral gene transfer (11). Finally, cytolysin, a toxin secreted by enterococci, derives its cytolytic activity from 2 peptides that possess modifications characteristic of lantibiotics (compounds with thioether amino acids that are derived by posttranslational modification from ribosomally synthesized precursors) (12, 13). Together these peptides lyse different host cells including polymorphonuclear leukocytes, a critical immune defense against E. faecalis infection (Figure 1) (14).

Figure 1. Role for pili in the establishment of E. faecalis infection.

Enterococci may use pili (surface fibrils) for microbial attachment to host tissues (i). Surface proteins (e.g., AS, Esp, and Ace) are involved in establishing tight bacterial adherence to host cells (ii). Enterococcal aggregation induces biofilm formation (iii) and elaboration of exopolysaccharide matrix (blue surface layer). Quorum-sensing–controlled expression of protease and cytolysin mediate host cell death and spread of infection (iv). Schematic modified with permission from ASM Press (1).

Pili occur even in gram-positive bacteria

The presence of pili on the surface of gram-positive bacteria has only recently been reported for several strains of Corynebacterium spp., Actinomyces spp., and Streptococcus spp. (15–17). By using antibodies as reagents for detection, adhesins at the pilus tip as well as major and minor pilin subunits were discovered (18). Structural genes encoding pilin subunits in C. diphtheriae and A. naeslundii are located in close proximity to genes encoding sortase-like enzymes (18–20). Sortases are transpeptidases that cleave sorting signals of surface proteins to immobilize their C-terminal carboxyl group via amide bond formation in the cell wall envelope of gram-positive bacteria such as staphylococci, listeria, or bacilli (21, 22). Mutations that abrogate sortase or pilin subunit gene expression abolish the formation of pili (18). A pilin motif sequence with a conserved lysine residue is found in all major pilin subunit genes, and this lysine residue is also essential for the formation of pili (18). Biochemical experiments demonstrated that gram-positive pili cannot be dissolved with SDS or organic solvents, but are cleaved by protease (23). Together these data suggest a model whereby sortases promote pilus assembly via the formation of transpeptide bonds between the C-terminal carboxyl group of cleaved pilin precursors and the side chain amino group of lysine residues in pilin motif sequences (24).

Several predictions can be derived from this model. First, gram-positive microbes whose genome sequences harbor clusters of genes that encode sortases as well as surface proteins with sorting signals and pilin motif sequences must produce pili (24). This prediction is fulfilled for enterococci in this issue of the JCI by Nallapareddy et al. (25) but also in other recent publications identifying pili on the surface of group B streptococci or pneumococci (26, 27).

Enterococcal pili

In a previous study, Sillanpää and colleagues queried enterococcal genome sequences for LPXTG motif–containing sorting signals (where X is any amino acid) and structural features of surface proteins such as 160- to 500-aa segments containing Ig-like folds (28). Three open reading frames, ef1091–ef1093, displayed such features, and antibodies against these proteins were found more often in sera of individuals infected with E. faecalis than in the sera of noninfected control patients (28). In this issue of the JCI, Nallapareddy et al. (25) further characterize ef1091–ef1093 and their associated sortase C (srtC), thereby revealing that these 3 open reading frames and srtC are part of an operon encoding endocarditis and biofilm–associated pili (ebp). The authors used immunogold electron microscopy to demonstrate the presence of pili composed of EbpA, EbpB, and EbpC on the surface of E. faecalis. Biofilm assays were used to show that a nonpiliated mutant was unable to form biofilms. When recovering microbes from aortic vegetations in a rat endovascular infection model, pilus mutants could not adequately compete with wild-type enterococci, suggesting that pili are required for the establishment of enterococcal infections. Using specific probes, the genes ebpA, ebpB, and ebpC were detected in 408 E. faecalis isolates from 4 continents, leading the authors to conclude that the formation of pili may be a ubiquitous trait of E. faecalis. Independent of this work, Tendolkar and colleagues recently identified a cluster of sortase and surface protein genes involved in biofilm formation (including biofilm enhancer in Enterococcus [bee]), although this study does not unveil the ability of enterococci to form pili (29).

If one assumes that pili — fibrous tools for bacterial adhesion to host tissues — are important for virulence, one could also speculate that immunization of animals or humans with pilin subunits may prevent microbial adhesion or the pathogenesis of infection. Two recent reports corroborate this contention, demonstrating that immunization of animals with pilin subunits prevent group B streptococcal neonatal meningitis or group A streptococcal infection (30, 31). Thus, the discovery of pili and pilus assembly in gram-positive bacteria not only promises new technology but may also generate public health measures that affect humans.

Conclusion

Sortase-anchored pili have been found in Corynebacterium spp., Actinomyces spp., group A and group B streptococci, pneumococci, and now in enterococci. In the current study (25), E. faecalis pili were found to play a major role in biofilm formation and appear to be important in mediating endovascular infection. As these ubiquitously encoded surface proteins are antigenic in humans during endocarditis infection, this study raises the possibility of potential new preventive measures that may disrupt the pathogenesis of enterococcal endocarditis.

Acknowledgments

Work on gram-positive pili in the laboratory of O. Schneewind is supported by United States Public Health Service Grant AI38897 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

Footnotes

Nonstandard abbreviations used: Ace, adhesion to collagen from E. faecalis; AS, aggregation substance; ebp, endocarditis and biofilm-associated pili; Esp, enterococcal surface protein; fsr, E. faecalis regulator; SrtC, sortase C.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J. Clin. Invest. 116:2582–2584 (2006). doi:10.1172/JCI30088.

See the related article beginning on page 2799.

References

- 1. Gilmore, M.S. 2002. The Enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. ASM Press. Washington, DC, USA. 439 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Megran D.W. Enterococcal endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1992;15:63–71. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giessel B.E., Koenig C.J., Blake R.L. Management of bacterial endocarditis. Am. Fam. Physician. 2000;61:1725–1732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fridkin S.K., Gaynes R.P. Antimicrobial resistance in intensive care units. Clin. Chest Med. 1999;20:303–316. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novick R.P. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:1429–1449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham M.W. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000;13:470–511. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.3.470-511.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillar C.M., Gilmore M.S. Enterococcal virulence--pathogenicity island of E. faecalis. . Front. Biosci. 2004;9:2335–2346. doi: 10.2741/1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rich R.L., et al. Ace is a collagen-binding MSCRAMM from Enterococcus faecalis. . J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26939–26945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shankar V., Baghdayan A.S., Huycke M.M., Lindahl G., Gilmore M.S. Infection-derived Enterococcus faecalis strains are enriched in esp, a gene encoding a novel surface protein. . Infect. Immun. 1999;67:193–200. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.193-200.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galli D., Wirth R. Comparative analysis of Enterococcus faecalis sex pheromone plasmids identifies a single homologous DNA region which codes for aggregation substance. . J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3029–3033. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3029-3033.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carniol K., Gilmore M.S. Signal transduction, quorum-sensing, and extracellular protease activity in Enterococcus faecalis biofilm formation. . J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:8161–8163. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8161-8163.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coburn P.S., Gilmore M.S. The Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin: a novel toxin active against eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. . Cell. Microbiol. 2003;5:661–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahl H.G., Bierbaum G. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis and biological activities of uniquely modified peptides from gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. . 1998;52:41–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coburn P.S., Pillar C.M., Jett B.D., Haas W., Gilmore M.S. Enterococcus faecalis senses target cells and in response expresses cytolysin. . Science. 2004;306:2270–2272. doi: 10.1126/science.1103996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanagawa R., Honda E. Presence of pili in species of human and animal parasites and pathogens of the genus Corynebacterium. . Infect. Immun. 1976;13:1293–1295. doi: 10.1128/iai.13.4.1293-1295.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yeung, M.K. 2000. Actinomyces: surface macromolecules and bacteria–host interactions. In Gram-positive pathogens. V.A. Fischetti, R.P. Novick, J.J. Ferretti, D.A. Portnoy, and J.I. Rood, editors. American Society for Microbiology. Washington, DC, USA. 583–593. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu H., Fives-Taylor P.M. Molecular strategies for fimbrial expression and assembly. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2001;12:101–115. doi: 10.1177/10454411010120020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ton-That H., Schneewind O. Assembly of pili on the surface of C. diphtheriae. . Mol. Microbiol. 2003;50:1429–1438. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeung M.K., Donkersloot J.A., Cisar J.O., Ragsdale P.A. Identification of a gene involved in assembly of Actinomyces naeslundii T14V type 2 fimbriae. . J. Bacteriol. 1998;66:1482–1491. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1482-1491.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li T., Khah M.K., Slavnic S., Johansson I., Stromberg N. Different type I fimbrial genes and tropisms of commensal and potentially pathogenic Actinomyces spp. with different salivary acidic proline-rich protein and statherin ligand specificities. . Infect. Immun. 2001;69:7224–7233. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7224-7233.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazmanian S.K., Liu G., Ton-That H., Schneewind O. Staphylococcus aureus sortase, an enzyme that anchors surface proteins to the cell wall. . Science. 1999;285:760–763. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ton-That H., Liu G., Mazmanian S.K., Faull K.F., Schneewind O. Purification and characterization of sortase, the transpeptidase that cleaves surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus at the LPXTG motif. . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:12424–12429. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ton-That H., Marraffini L., Schneewind O. Sortases and pilin elements involved in pilus assembly of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. . Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:1147–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ton-That H., Schneewind O. Assembly of pili in gram-positive bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2004;12:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nallapareddy S.R., et al. Endocarditis and biofilm-associated pili of Enterococcus faecalis. . J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2799–2807. doi: 10.1172/JCI29021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauer P., et al. Genome analysis reveals pili in Group B Streptococcus. Science. 2005;309:105. doi: 10.1126/science.1111563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barocchi M.A., et al. A pneumococcal pilus influences virulence and host inflammatory responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:2857–2862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511017103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sillanpaa J., Xu Y., Nallapareddy S.R., Murray B.E., Höök M. A family of putative MSCRAMMs from Enterococcus faecalis. . Microbiology. 2004;150:2069–2078. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27074-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tendolkar P.M., Baghdayan A.S., Shankar N. Putative surface proteins encoded within a novel transferable locus confer a high-biofilm phenotype to Enterococcus faecalis. . J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2063–2072. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.6.2063-2072.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maione D., et al. Identification of a universal group B streptococcus vaccine by multiple genome screen. Science. 2005;309:148–150. doi: 10.1126/science.1109869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mora M., et al. Group A Streptococcus produce pilus-like structures containing protective antigens and Lancefield T antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:15641–15646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507808102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]