Abstract

PURPOSE This case study describes the findings of a physician workforce analysis and how an institution is using these findings to address the decreasing proportion of medical students choosing primary care careers.

METHODS A University of Washington School of Medicine committee commissioned an analysis of the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile. The analysis examined physician-to-population ratios, rural-urban geographic distribution, physician demographics, and physician graduation from the university or one of its affiliated residency programs for graduates of allopathic medical schools and residencies at the county level in the 5 states in the WWAMI partnership (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho).

RESULTS The analysis found that in 2005, the 5 WWAMI states ranked at the bottom of US states in the number of publicly supported medical school and residency slots per capita. Although physician-to-population ratios were comparable to those in the rest of the country, the 5 WWAMI states imported most of their physicians, including family physicians, approximately 70% of whom came from other medical schools or residency programs. Family physicians were the only specialty distributed across the population gradient from urban to isolated rural areas. The workforce analysis is informing planning for medical school expansion, admissions, support for primary care, curriculum, and research at an institution with a clear mission that includes training the health workforce for its region.

CONCLUSIONS The analysis has wide potential applicability, but it has special relevance for primary care and has been particularly useful in making the case for supporting primary care education in the WWAMI region.

Keywords: Medical education; medical schools; workforce planning; training; primary care; physicians, family

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the proportion of students choosing careers in primary care has declined precipitously in the United States. The pattern at the University of Washington (UW) has followed the national trend, but at a somewhat slower rate. In 1996, more than 60% of UW students chose careers in primary care (family medicine, general internal medicine, or general pediatrics), but in 2005, fewer than 30% of students did so. This trend has been followed with increasing alarm by the UW’s many educational partners in the 5 states in WWAMI (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho), a partnership between the UW School of Medicine and nearby states.

The UW has a dual mission to meet the health care needs of the 5-state WWAMI region, particularly by recognizing the importance of primary care, and to advance knowledge and assume leadership in the biomedical sciences and in academic medicine. The university is widely recognized for its success in both domains, with high rankings in both primary care and research.

METHODS

In the summer of 2003, UW School of Medicine Dean Paul Ramsey appointed an ad hoc committee to examine the decline in interest among graduating students in primary care, especially family medicine. In June 2004, the committee presented its report to the dean and the medical school’s executive committee (the deans and department chairs), which then approved 5 principles that are consistent with the mission of the UW School of Medicine (Table 1 ▶). Dean Ramsey appointed a primary care steering committee in the summer of 2004 with 4 tasks: assist in the review of admissions, assess support for specialty choices in primary care, assess the need and demand for residency positions in primary care, and develop a public policy agenda at the state level. The committee had members including key deans and department chairs, and was chaired by the chair of the Department of Family Medicine, Alfred Berg, MD, MPH.

Table 1.

Principles Approved at the University of Washington School of Medicine Executive Committee Meeting, June 4, 2004

|

WWAMI = a partnership between the University of Washington School of Medicine and the states of Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho.

The committee quickly realized that it had only fragmentary information regarding the WWAMI health workforce on which to build programs that might advance primary care. Accordingly, the committee commissioned Frederick M. Chen, MD, MPH, Meredith A. Fordyce, PhC, and L. Gary Hart, PhD, in the WWAMI Center for Health Workforce Studies in the Department of Family Medicine to conduct an analysis using existing databases. The investigators chose the current American Medical Association Physician Masterfile1 because it is comprehensive and its strengths and limitations are well known.

The investigators’ methods are fully described in the resulting report, WWAMI Physician Workforce 2005,2 which is available online (http://fammed.washington.edu/CHWS/). Briefly, the investigators identified all allopathic physicians practicing in the WWAMI states and determined their discipline, site of medical school and residency training, and current zip code. Rural-urban characteristics were analyzed using the RUCA (Rural-Urban Commuting Area) system.

RESULTS

Key Findings

Full results of the analysis are available on the aforementioned Web site. The analysis produced data regarding physician-to-population ratios, rural-urban geographic distribution, physician demographics, and physician graduation from the UW or one of its affiliated residency programs for all graduates of allopathic medical schools and residencies down to the county level in the 5 WWAMI states. These were the key findings:

Physician-to-population ratios in the 5 WWAMI states were comparable to those in the rest of the country for most specialties overall but were higher for family medicine.

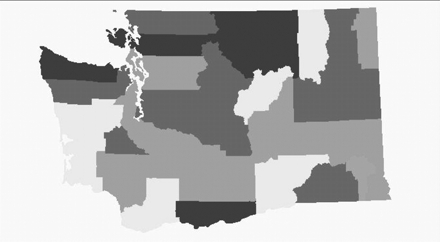

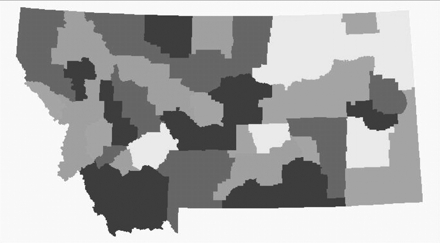

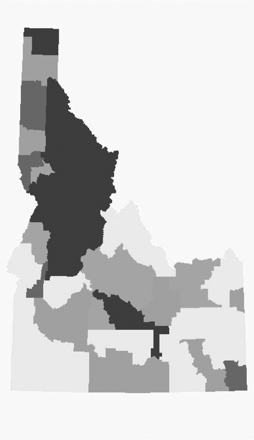

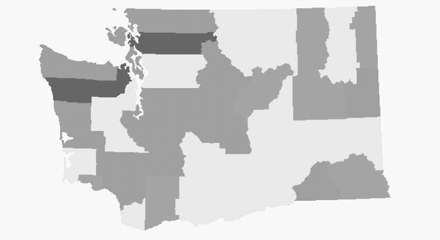

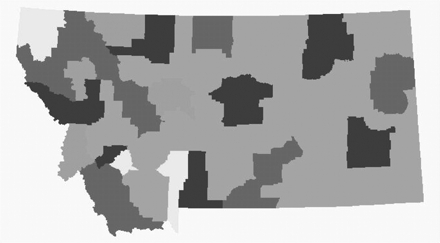

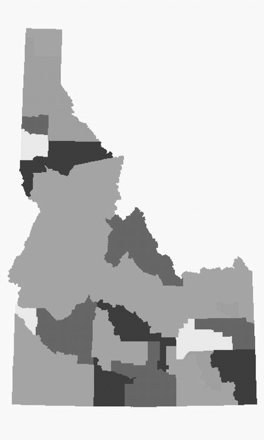

Family physicians were the only specialty distributed along the population gradient, from urban to isolated rural communities. Figures 1 ▶ and 2 ▶ display illustrative state maps for family physicians and general surgeons, respectively, illustrating differences in physician-to-population ratios and geographic distributions.

The WWAMI states imported most of their physicians (ie, most physicians neither graduated from UW nor did a residency in one of the states). Washington State imported nearly 60% of its physicians, and the other WWAMI states imported more than 90%. (The obvious implications of this finding for workforce planning in other regions and nationally are outside the scope of this report.) The “best” finding of the analysis was that 45% of family physicians in Washington State either went to medical school or did their residency in the state.

The 5 WWAMI states ranked near the bottom of all states in the number of publicly supported medical school and residency slots per capita.

Figure 1.

Number of family physicians per 10,000 population, by county, in the WWAMI states (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho).

Reprinted with permission from Chen et al.2

Figure 2.

Number of general surgeons per 10,000 population, by county, in the WWAMI states (Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho).

Reprinted with permission from Chen et al.2

Outcomes

The primary care steering committee viewed the analysis as a cross-sectional snapshot and could not make causal inferences. For example, the committee could not directly assess the need and demand for physicians of any specialty from the analysis. The better distribution of family physicians compared with other specialists by population gradient was interpreted as likely due to the strong historical emphasis of the UW on primary care and the rural nature of the 5 states.

The entire report was presented to the medical school’s executive committee (deans and department chairs). In addition to being used by the primary care steering committee, the findings are now informing several concurrent projects, described below.

Medical School Expansion

The UW School of Medicine annually admits 120 students from Washington, 10 from Wyoming, 10 from Alaska, 20 from Montana, and 18 from Idaho—numbers that have not much changed in many years. Discussions are now under way in all 5 states to substantially increase class size. Wyoming has already committed to a phase-in of 6 additional students per year over the next 3 years. Senior UW administrative officials estimate that class size could expand by as many as 50 students per year over the next decade. Although this would be a marked expansion, the 5 WWAMI states would still be well below national averages in terms of number of seats per capita. To reach the national average, we would need to more than double in size.

Medical School Admissions

The UW School of Medicine conducted a yearlong review of admissions policies and processes. A key recommendation, accepted by the dean and executive committee, is that the admitted class should reflect the school’s mission and goals with respect to workforce needs and population demographics. The outputs of the school by specialty and location will become criteria that the admissions committee will use to track its effectiveness.

Primary Care Pathway

The dean has approved a recommendation to develop a pathway in primary care, perhaps modeled on successful programs from the university’s past or on programs currently in operation elsewhere. Such a pathway would probably be integrated with a new admissions process, to maximize the likelihood that graduates will enter primary care specialties in areas of need. A detailed recommendation is expected by the spring of 2006.

Curriculum

The school completed a major review and restructuring of its curriculum within the last 5 years. One of the principal innovations is the division of the entering class into “colleges” staffed by an interdisciplinary group of 30 faculty (more than one third of whom are primary care physicians) committed to the early clinical education of students. This group of faculty has taken on development of a curriculum in professionalism that includes dealing with the problem of disrespect for specialty choice that especially disadvantages primary care.

Research

The completed WWAMI workforce analysis was a good beginning, but many issues must still be addressed. The analysis will be expanded to include other clinicians (eg, osteopathic physicians) and also to begin to examine the much more difficult questions surrounding physician need and demand. This process must occur in the midst of the national debate regarding workforce planning in which the older “need” model based on projections that assumed an integrated delivery system of generalists and specialists is being supplanted by a “demand” model that basically proposes that we should be training physicians to meet whatever the market demands.

DISCUSSION

The case presented in this article began with the premise that a publicly supported medical school should aim to meet the needs of its region in terms of physician workforce. The UW continues to embrace this mission with its partners in the 5 WWAMI states. A basic understanding of the health workforce in the region is critical before envisioning new programs or changing old ones to meet the needs. The cross-sectional data from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile have been extremely useful in planning the first steps. The total cost of the analysis, including the data files, investigator time, and report production and dissemination, was less than $50,000.

The UW is using WWAMI workforce data to inform decisions about medical school class size, admissions, a primary care pathway, curriculum, and research. This case presents a model for using readily available workforce data to inform the processes and outcomes of medical education in a large publicly supported medical school.

Conflicts of interest: none reported

REFERENCES

- 1.AMA Physician Masterfile. 2004. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2673.html. Accessed 10 April 2006.

- 2.Chen FM, Fordyce MA, Hart LG. WWAMI Physician Workforce 2005. Seattle, Wash: WWAMI Center for Health Workforce Studies; 2005. Working Paper 98. Available at: http://www.depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/CHWSWP98.pdf.