Abstract

Membrane-impermeant quaternary derivatives of lidocaine (QX222 and QX314) block cardiac Na+ channels when applied from either side of the membrane, but they block neuronal and skeletal muscle channels poorly from the outside. To find the molecular determinants of the cardiac external QX access path, mutations of adult rat skeletal muscle (μ1) and rat heart (rH1) Na+ channels were studied by two-electrode voltage clamp in Xenopus oocytes. Mutating the μ1 domain I P-loop Y401, which is the critical residue for isoform differences in tetrodotoxin block, to the heart sequence (Y401C) allowed outside QX222 block, but its mutation to brain type (Y401F) showed little block. μ1-Y401C accelerated recovery from block by internal QX222. Block by external QX222 in μ1-Y401C was diminished by chemical modification with methanethiosulfonate ethylammonium (MTSEA) to the outer vestibule or by a double mutant (μ1-Y401C/F1579A), which altered the putative local anesthetic binding site. The reverse mutation in heart rH1-C374Y reduced outside QX314 block and slowed dissociation of internal QX222. Mutation of μ1-C1572 in IVS6 to Thr, the cardiac isoform residue (C1572T), allowed external QX222 block, and accelerated recovery from internal QX222 block, as reported. Blocking efficacy of outside QX222 in μ1-Y401C was more than that in μ1-C1572T, and the double mutant (μ1-Y401C/C1572T) accelerated internal QX recovery more than μ1-Y401C or μ1-C1572T alone. We conclude that the isoform-specific residue (Tyr/Phe/Cys) in the P-loop of domain I plays an important role in drug access as well as in tetrodotoxin binding. Isoform-specific residues in the IP-loop and IVS6 determine outside drug access to an internal binding site.

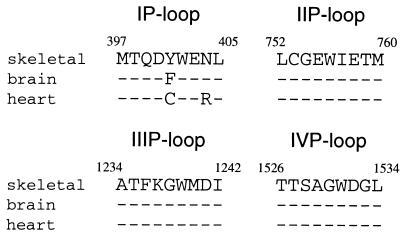

Voltage-gated Na+ channels are membrane proteins responsible for generation of action potentials in nerve, skeletal muscle, and heart. The Na+ channel α-subunit consists of four homologous domains (I–IV), each containing six transmembrane segments (S1–S6) (1, 2). P-loops connecting S5 and S6 in each domain form the Na+ channel outer vestibule (3–7). Na+ channel isoforms from various tissues are highly homologous (2, 8). However, cardiac channels are relatively insensitive to tetrodotoxin (TTX) compared with brain and skeletal muscle channels (9, 10). This isoform difference is explained by an isoform-specific residue (Tyr/Phe/Cys) in the P-loop of domain I (IP-loop) (11–14) (Fig. 1). An aromatic residue at this position renders the channel TTX sensitive.

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of pore-forming regions (P-loops) of four domains of different Na+ channel isoforms. Amino acid sequences are from μ1, rat brain IIA, and rH1. Nine residues are assigned to P-loop from each domain and numbers indicate the amino acid position of μ1. Identical amino acids are indicated with dashes.

The Na+ channel is also the site of action of local anesthetic antiarrhythmic drugs. Two conserved aromatic residues (Phe and Tyr) in IVS6 are involved in the local anesthetic binding site (15–17), and isoform differences in local anesthetic affinity are much less than in toxin affinity (18). In contrast, access of local anesthetic drugs differs markedly between Na+ channel isoforms. Quaternary membrane-impermeant derivatives of lidocaine such as QX314 and QX222 do not block nerve channels when applied to the outside (19, 20), but outside QX314 blocks the cardiac channel (21). This block can be reduced by prior treatment with TTX, suggesting that QX may travel through the pore to reach an internal binding site (16). Qu et al. (16) found that Thr, a cardiac isoform-specific residue near the extracellular end of IVS6, is a determinant of QX314 access from the outside. Access through the pore is not expected because the size of the channel selectivity filter is much smaller than the dimensions of the QX molecules (22), and the two channel isoforms are equally selective for Na+ and for organic cations.

The P-loops between S5 and S6 of each domain that form the outer vestibule and selectivity filter are highly conserved among isoforms (2, 8) (Fig. 1). Only two residues in the four P-loop SS2 segments are different, Tyr-401 (numbering of μ1, the adult rat skeletal muscle Na+ channel) in place of Phe (brain) or Cys (heart), and Asn-404 (skeletal muscle and brain) in place of Arg (heart). If QX access is through the pore, Tyr/Phe/Cys would be more likely to influence QX access than Asn/Asn/Arg because Tyr/Phe/Cys is one residue C-terminal to the selectivity filter (23, 24). The residue at this position is thought to be located within the water-filled vestibule, rather than buried in the protein because it interacts strongly with the charged guanidinium toxins (11–14). The site is also accessible to Cd2+ and Zn2+ (11–13, 25), and it can form disulfide bridges with Cys introduced in other P-loops (26). We report here that Tyr/Phe/Cys, in addition to controlling isoform TTX sensitivity, is a critical structural feature determining QX access to its inside site of action.

Materials and Methods

The μ1 cDNA flanked by the Xenopus globulin 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (provided by J. R. Moorman, Univ. of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA) and the rat heart Na+ channel (rH1) cDNA preceded by the 5′ untranslated region (provided by R. Kallen, Univ. of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) were both subcloned into the Bluescript SK vector (Promega). Oligonucleotide-directed point mutations were introduced by using the following methods. The Y401C and Y401D mutations in μ1 were made by using the Unique Site Elimination Mutagenesis Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Pharmacia). The Y401A, Y401F, C1572T, and F1579A mutations in μ1 and the C374Y mutation in rH1 were made by using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Stratagene). Mutagenic oligonucleotide primers included the desired mutations as well as changes in silent restriction sites. Mutations identified as positive through qualitative restriction mapping were confirmed by DNA sequencing of regions containing the mutation between unique restriction sites. These regions were subsequently used in reconstruction of the full-length μ1 and rH1 cDNA in Bluescript SK. Double mutants were made by subcloning the region of the μ1-Y401C containing the mutation between unique restriction sites into the μ1-C1572T or μ1-F1579A construct. The μ1 and rH1 vectors were both linearized by NotI. All templates were transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase by using the T7 Message Machine Kit according to the manufacturer's protocols (Ambion, Austin, TX).

Stage V and VI Xenopus oocytes were isolated, and approximately 50–100 ng of cRNA was injected into each oocyte. Oocytes were incubated at 16°C for 1 to 6 days before examination. Recordings were made in the two-electrode voltage clamp configuration by using a CA-1 voltage clamp (Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, MN), as reported (27). All recordings were made at room temperature (20–22°C) in a bathing solution that consisted of 90 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.2). QX314 and QX222 were obtained from Alomone (Jerusalem). QX222 was used in most of the experiments because of its faster kinetics of block and unblock, but otherwise it was not different from QX314. Methanethiosulfonate ethylammonium (MTSEA) was obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals (North York, ON, Canada). Pooled data are presented as the means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made by using Student's t test, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Cardiac, But Not Skeletal Muscle Na+ Channels Are Sensitive to External QX.

We first compared the sensitivity of μ1 and rH1 to external QX in the oocyte expression system. Because μ1 α-subunits display a much slower time course of inactivation and recovery than that of rH1 α-subunits when expressed in Xenopus oocytes (28–30), we coexpressed these α-subunits and human brain β1-subunits (provided by G. S. Tonkovich and J. W. Kyle, Univ. of Chicago, Chicago, IL). When currents were elicited by 35-ms pulses to −20 mV from a holding potential of −110 mV at 5-s intervals, μ1-β1 showed no block (1.0 ± 0.9% block, n = 4) 12 min after external application of 500 μM QX314, but rH1–β1 showed 30.6 ± 2.8% block (n = 5) (not shown). The effectiveness of external QX block in cardiac channels is consistent with the reported effects on native Na+ channels of cardiac Purkinje fibers (21) and rH1 expressed in tsA-201 cells (16). Because skeletal muscle channels were much less sensitive to external QX than cardiac channels were under similar conditions in the oocyte expression system, we used mutants of the μ1 α-subunit to see if the isoform-specific residue of the IP-loop contributes to isoform differences of QX block.

Mutation of the Isoform-Specific Residue of μ1 IP-Loop to Heart Sequence (μ1-Y401C) Allows External QX to Reach the Internal Binding Site.

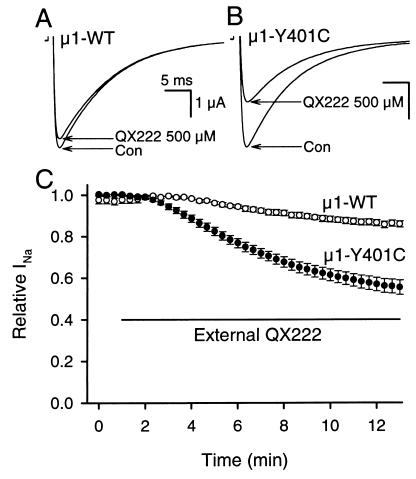

We examined the effects of externally applied 500 μM QX222 on μ1 wild type (μ1-WT) and its mutant of IP-loop to the heart sequence, μ1-Y401C (Fig. 2). When stimulated at 20-s intervals with 35-ms pulses to −10 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV, μ1-WT showed little block (Fig. 2A), but μ1-Y401C allowed obvious block during exposure to 500 μM QX222 in the bath solution (Fig. 2B). Twelve minutes after external application of 500 μM QX222, μ1-Y401C resulted in a significant block compared with μ1-WT (WT, 14.2 ± 1.6% block, n = 8; Y401C, 45.2 ± 3.6% block, n = 9; P < 0.001) (Fig. 2C). The μ1-Y401C mutation did not change the time course or voltage-dependence of the current (not shown).

Figure 2.

Mutation of the isoform-specific residue of μ1 IP-loop to heart sequence (μ1-Y401C) allows block by external QX222. (A and B) Typical current traces before (con) and 12 min after external application of 500 μM QX222 recorded from (A) μ1-WT and (B) μ1-Y401C. (C) Effects of externally applied 500 μM QX222 on μ1-WT (○) and μ1-Y401C (●). The bar indicates the period of exposure to 500 μM QX222 in the bath solution. Data represent the means ± SEM from eight oocytes for μ1-WT and nine for μ1-Y401C. Currents were elicited by 35-ms pulses to −10 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV at 20-s intervals (A–C), and peak currents were normalized to peak current in control and plotted as relative Na+ currents (relative INa) (C).

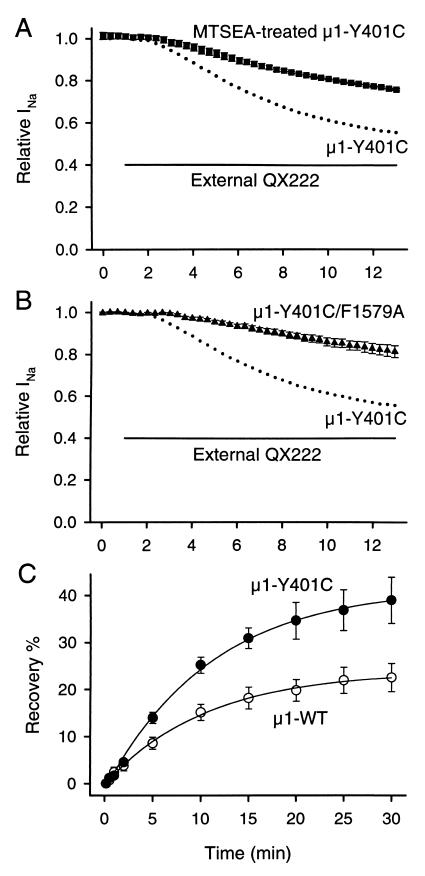

If μ1-Y401C creates an access pathway from the outside through the pore, specific chemical modification by MTSEA to Cys-401 might inhibit access of QX222. To test this prediction, we first applied 2.5 mM MTSEA to the bath solution before exposing to external QX222; 2.5 mM MTSEA blocked 73.5 ± 1.9% (n = 5) of the μ1-Y401C current during 3- to 5-min perfusion when stimulations were applied at 20-s intervals. After washout of MTSEA for at least 5 min, the residual currents were further examined for external QX222 block. After a 12-min perfusion with 500 μM QX222, the MTSEA-modified μ1-Y401C channel showed 24.7 ± 0.4% block (n = 4), significantly less than that of μ1-Y401C (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). Also, MTSEA modification significantly reduced the rate of onset of QX222 block (Y401C, τ = 371 ± 22 s, n = 9; MTSEA-modified Y401C, τ = 656 ± 104 s, n = 4; P < 0.01). This result implied that MTSEA modification in the outer vestibule interfered with access of QX222. The Na+ channel pore can also be blocked by μ-conotoxin, a 22-amino acid peptide toxin that binds superficially to the outer vestibule (31, 32). The toxin mutant R13Q blocks the channel with a small residual current. Block with a saturating concentration of R13Q also significantly reduced QX222 block of the μ1-Y401C current (not shown). These results are similar to the reports stating that TTX (16, 27) and neo-saxitoxin (27) protected the channels from outside QX314 block.

Figure 3.

μ1-Y401C creates an access pathway for external QX222 to reach the internal binding site. (A) Effects of MTSEA modification in the outer vestibule on block by external QX222 in μ1-Y401C. MTSEA modification was done by bath application of 2.5 mM MTSEA for 3–5 min and verified by irreversibility of current reduction after washout for at least 5 min before external application of QX222. (B) Effects of mutation of the putative local anesthetic binding site (μ1-F1579) on block by externally applied QX222 in μ1-Y401C. For this, actions of externally applied QX222 were studied for the double mutant, μ1-Y401C/F1579A. In A and B, the protocol was the same as that in Fig. 2, and peak currents were normalized to that in the control. Data represent the means ± SEM from four oocytes for MTSEA-bound μ1-Y401C (■) and five for μ1-Y401C/F1579A (▴). In each panel, the mean values (●) of block for μ1-Y401C shown in Fig. 2C were represented to compare the block development. The bar indicates the period during exposure to 500 μM QX222 in the bath solution. (C) Effects of μ1-Y401C on recovery from internally applied QX222 block. QX222 was internally applied by microinjecting 50 nl of a 3 mM QX222 solution into oocytes. Twenty to thirty minutes after microinjection, a 1-Hz train of 20 pulses with 35-ms duration was applied to −10 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV to produce use-dependent block by QX222. Then, recovery from the QX222 block was monitored at the indicated intervals after the end of a train for μ1-WT (○) and μ1-Y401C (●). Peak currents during recovery were normalized by the difference between the peak current during the first pulse of a train and the 10-s recovery test pulse, and plotted as recovery %. The 10-s recovery was assumed to allow recovery from inactivation of unblocked channels but be short enough to prevent QX222 dissociation from blocked channels. The smooth lines are single exponential fits, and data represent the means ± SEM from six oocytes for μ1-WT and five to seven for μ1-Y401C.

An important part of the local anesthetic binding site is thought to include Phe-1764 in the midportion of rat brain IIA IVS6 (15–17). To confirm that μ1-Y401C is creating an access path to this putative inside binding site rather than creating a new outside site, the double mutant composed of Y401C and F1579A in IVS6 (μ1-Y401C/F1579A) was constructed and tested. μ1-F1579 is equivalent to F1764 of rat brain. When 500 μM QX222 was applied to the bath solution for 12 min, the double mutant μ1-Y401C/F1579A showed significantly less external block (18.8 ± 2.8%, n = 5, P < 0.001) with reduction of onset rate (τ = 4,067 ± 1,371 s, n = 5, P < 0.01) compared with the single mutant, μ1-Y401C (Fig. 3B). This finding supported the idea that μ1-Y401C created an access pathway for external QX222 to reach its internal binding site.

If there is indeed an access pathway to the internal site, it would also provide an alternative path for dissociation of the bound drug (15, 16, 27). To compare recovery from QX222 block in μ1-WT and μ1-Y401C, QX222 was microinjected into oocytes by using the same procedure as before (27). Consistent with our previous report on recovery of the μ1 channels from QX314 block (27), recovery of QX222 in μ1-WT was also slow, with 22.5 ± 3.0% (n = 6) of the current recovering during a 30-min period (Fig. 3C). On the other hand, μ1-Y401C significantly accelerated recovery and 38.9 ± 4.9% (n = 5) of the current recovered during a 30-min period (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3C). This result further supports the proposal that μ1-Y401C allows external QX block by creating an access pathway to the internal binding site and this pathway also provides an escape route for QX to the outside.

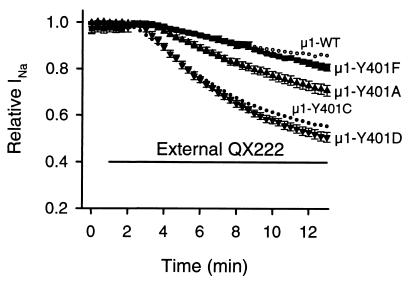

Effects of Other μ1-Y401 Mutations on External QX Block.

Because the Cys mutant at position 401 allowed block by externally applied QX222, we studied the effects of replacement of μ1-Y401 with other amino acids. Substitution of Tyr with a smaller residue, Ala (μ1-Y401A) showed a significant block (29.8 ± 2.1%, n = 7) during 12-min exposure to external 500 μM QX222 compared with μ1-WT (P < 0.001), smaller than that of μ1-Y401C (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4). Substitution of Tyr with a smaller and negatively charged residue, Asp (μ1-Y401D) significantly increased block (49.6 ± 2.2%, n = 5, P < 0.001). In contrast, mutation of Tyr to a similar sized residue, Phe as in the brain channel (μ1-Y401F) resulted in block not different from μ1-WT (19.4 ± 1.5%, n = 4, P > 0.05) (Fig. 4). These results and the fact that Cys is smaller than Tyr suggest that bulky residues at position 401 impede QX222 access.

Figure 4.

Effects of substitution of μ1-Y401 with other amino acids on external QX222 block. Actions of externally applied 500 μM QX222 were studied for μ1-Y401F (▪), μ1-Y401A (▴), and μ1-Y401D (▾). For comparison, the mean values of block for μ1-WT (○) and μ1-Y401C (•) shown in Fig. 2C were represented. The bar indicates the period of exposure to 500 μM QX222 in the bath solution. The protocol was the same as that in Fig. 2, and peak currents were normalized to that in control. Data represent the means ± SEM from four oocytes for μ1-Y401F, seven for μ1-Y401A, and five for μ1-Y401D.

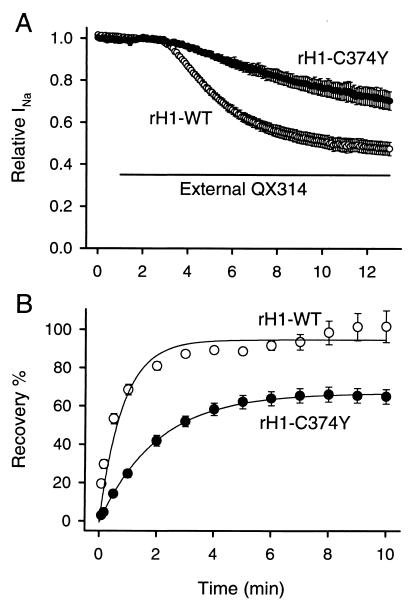

Reverse Mutation of Heart to μ1 Sequence (rH1-C374Y) Inhibits External QX Block.

Consistent results were also observed in the rat heart analogous mutation. Tyr-401 in μ1 is equivalent to Cys-374 in rH1. When 500 μM QX314 was applied to the bath solution for 12 min, rH1-WT showed 52.5 ± 3.1% block (n = 7) in response to a train of 35-ms pulses to −20 mV from a holding potential of −110 mV at 5-s intervals (Fig. 5A). rH1-C374Y significantly slowed the onset rate of QX314 block (rH1-WT, τ = 170 ± 5 s, n = 7; rH1-C374Y, τ = 672 ± 100 s, n = 5; P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). When comparing the recovery from internally applied QX222 block, rH1-WT showed a recovery time constant of 49 s and recovery was complete (101.7 ± 8.3%, n = 4) during a 10-min period (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, rH1-C374Y showed slower recovery (time constant of recovery was 120 s) and recovery amount was significantly decreased (65.0 ± 3.8%, n = 4, P < 0.01) (Fig. 5B). There was no effect of the rH1-C374Y mutation on time course or voltage dependence of the current (not shown). These findings suggest that Cys in the cardiac IP-loop is a critical structural feature determining QX access.

Figure 5.

Reverse mutation of rH1 to μ1 sequence (rH1-C374Y) inhibits block by external QX and slows down dissociation of internally applied QX. (A) Effects of externally applied QX314 on rH1-WT (○) and rH1-C374Y (●). The bar indicates the period during exposure to 500 μM QX314 in the bath solution. Currents were elicited by 35-ms pulses to −20 mV from a holding potential of −110 mV at 5-s intervals, and peak currents were normalized to peak current in control. Data represent the means ± SEM from seven oocytes for rH1-WT and five for rH1-C374Y. (B) Effects of rH1-C374Y on recovery from internally applied QX222 block. QX222 was internally applied by microinjecting 50 nl of a 3 mM QX222 solution into oocytes. Twenty to thirty min after microinjection, a 1-Hz train of 20 pulses with 35-ms duration was applied to −20 mV from a holding potential of −110 mV to produce use-dependent block by QX222. Then, recovery from QX222 block was monitored at the indicated intervals after the end of a train for rH1-WT (○) and rH1-C374Y (●). Peak currents during recovery were normalized by the difference between the peak current during the 1st and 20th pulses of a train, and plotted as recovery %. The smooth lines are single exponential fits, and data represent the means ± SEM from four to eight oocytes for rH1-WT and three to four for rH1-C374Y.

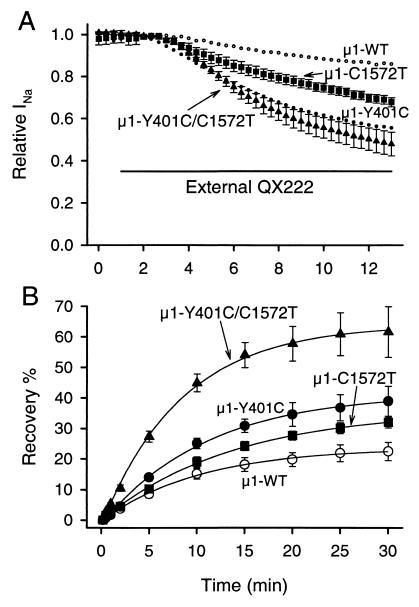

Isoform-Specific Residues of IP-Loop and IVS6 Are Involved in the Access Pathway of External QX.

Mutation of T1755 of rH1 IVS6 to the residue found in the brain sequence (T1755V) reduces block by external QX314 and slows recovery from drug block (16). Because the corresponding residue in μ1 is C1572, we examined the effects of its mutation to heart sequence (μ1-C1572T) to determine whether this residue in μ1 also prevents QX access from the outside. Consistent with the previous report with the rH1 isoform (16), μ1-C1572T allowed significant block (32.3 ± 2.1%, n = 6, P < 0.001) compared with μ1-WT 12 min after perfusion of 500 μM QX222 (Fig. 6A). Also, μ1-C1572T significantly increased the amount of recovery from internal QX222 block (32.0 ± 1.8%, n = 4, P < 0.05 vs. WT) during a 30-min period (Fig. 6B). In comparison, external QX222 block of μ1-Y401C was significantly greater than that of μ1-C1572T (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). μ1-Y401C also showed more recovery than μ1-C1572T, but this was not significant (P = 0.277) (Fig. 6B). Because in the μ1 channel both Y401 in the IP-loop and C1572 in IVS6 appeared to reduce access of outside QX, we constructed the double mutant composed of Y401C and C1572T (μ1-Y401C/C1572T). In μ1-Y401C/C1572T, 500 μM QX222 blocked 52.1 ± 5.6% (n = 5) of the current during 12-min perfusion, which is significantly greater than that in μ1-C1572T (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, μ1-Y401C/C1572T showed faster recovery than that of μ1-Y401C or μ1-C1572T alone (time constants of recovery were 498 s for Y401C/C1572T, 657 s for Y401C, and 818 s for C1572T) and significantly increased the extent of recovery (61.6 ± 8.3%, n = 3, P < 0.05 vs. Y401C, P < 0.01 vs. C1572T) (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that Y401 in the IP-loop and C1572 in IVS6 are both key residues to render the μ1 channel insensitive to external QX, and conversely that C374 and T1755 in the rH1 channel contribute to the QX access path to the internal binding site.

Figure 6.

Isoform-specific residues of IP-loop and IVS6 determine external QX access. (A) Effects of IVS6 mutant and double mutant of IP-loop and IVS6 on block by externally applied QX222. Actions of externally applied 500 μM QX222 were studied for μ1-C1572T (▪) and μ1-Y401C/C1572T (▴). The mean values of block for μ1-WT (○) and μ1-Y401C (•) are from Fig. 2C. The bar indicates the period of exposure to 500 μM QX222 in the bath solution. The protocol was the same as that in Fig. 2, and peak currents were normalized to that in control. Data represent the means ± SEM from six oocytes for μ1-C1572T and five for μ1-Y401C/C1572T. (B) Effects of μ1-C1572T and μ1-Y401C/C1572T on recovery from internally applied QX222 block. Recovery from QX222 block was monitored at the indicated intervals after use-dependent block by 1-Hz stimulation for μ1-C1572T (■) and μ1-Y401C/C1572T (▴). Recovery data for μ1-WT (○) and μ1-Y401C (●) are from Fig. 3C. The smooth lines are single exponential fits, and data represent the means ± SEM from four to five oocytes for μ1-C1572T and three for μ1-Y401C/C1572T. For others, see Fig. 3C.

Discussion

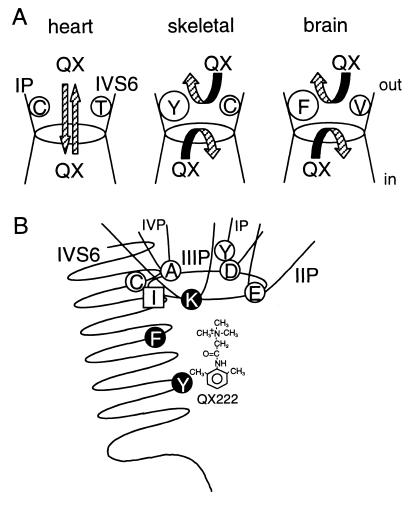

Extensive studies have shown that local anesthetic drugs typically access their binding site within the Na+ channel pore from the inside (22), and consequently, membrane-impermeant quaternary analogs fail to block nerve and skeletal muscle Na+ channels from the outside (16, 19, 20, 27, and this report) (Fig. 7A). However, the native cardiac channel and the rH1 α-subunit expressed in oocytes or mammalian cells can be blocked from the outside by the QX analogs (refs. 16 and 21, and this report). Does QX access its inside binding site via the normal ion permeation path or through some other region of the protein? Charged molecules can permeate slowly through proteins, so the QX pathway could bypass the vestibule and selectivity filter in transit to the internal binding site. Mutations made in the vicinity of the selectivity filter of the channel could alter the structure in unexpected and subtle ways, enhancing a path like the “hydrophobic” pathway for local anesthetic unbinding suggested by Hille (22). The evidence from previous studies (16, 27) and this report favor QX transit through the pore itself because the guanidinium toxins and μ-conotoxin and MTSEA modification of Cys in the vestibule all protect from outside QX block, and because mutations of the selectivity filter itself create an access path (27). In addition to being produced by mutation (15, 27), the path is found in unmodified cardiac channels (16, 21). This proposed mechanism is illustrated in Fig. 7. However, our experiments do not exclude a protein path.

Figure 7.

(A) A model for isoform differences of QX permeation in the Na+ channels. In the heart channel, QX can access to the internal binding site from the outside, and escape to the outside from the cytoplasmic side (16, 21). In skeletal muscle and brain channels, access and escape of QX are limited because of their aromatic residues on the IP-loop (present study), and Cys and Val on IVS6 (16, the present study). (B) Hypothetical pore structure of the Na+ channel composed of four P-loops and IVS6 with respect to access and binding of local anesthetics. Residues shown by open circles (D400, Y401, E755, A1529, and C1572; numbering of μ1) represent the amino acids affecting QX access from the outside (refs. 16 and 27, and the present study) and closed circles (K1237, F1579, and Y1586) affecting local anesthetic binding (15, 17, 27). Ile in square (I1575) appears to affect both access and binding of local anesthetics (15). The DEKA locus (Asp-Glu-Lys-Ala) forms the selectivity ring, shown here as an oval (23).

We find that the effects of both the IP-loop and IVS6 residues are additive, so both residues are important in defining the isoform difference in QX permeation. The additive effects of these two residues raise the question if these two residues in the IP-loop and IVS6 helix are adjacent in the three-dimensional structure of the Na+ channel vestibule, thereby contributing to a single-drug access path, or if they create separate paths. The crystal structure of the KcsA channel, a possible evolutionary ancestor of the Na+ channel, has revealed a close relationship between the P-loop and M2 in formation of the K+ channel pore (33). It is interesting to note that, except for the bulky aromatic residues, the efficacy of a QX block of μ1-Y401 substitutions was Asp > Cys > Ala, suggesting that a more hydrophilic residue favors QX access. This is a similar pattern to the efficacy of the QX block of Thr > Cys > Val for the IVS6 isoform-specific residues.

External Na+ can alter local anesthetic block (34). The cardiac isoform appears to have a somewhat lower single-channel conductance (12, 35, 36), and this might alter the local Na+ concentration near the site where it affects the QX block, making the cardiac channel more sensitive to the QX block than the higher conductance μ1 or nerve channels. This also seems unlikely because the rates of recovery from inside block, presumably by egress of drug to the outside, are also increased in the cardiac isoform and by the mutations allowing outside QX block.

The phenomenon of access of outside local anesthetic to its site of action could have important implications for the pharmacokinetics of these drugs, which is a key factor in their clinically valuable use-dependent property. Although our studies have been made with QX, it is likely that clinically useful drugs also share this access path (21). The results also suggest a possible structural basis for isoform differences in local anesthetic state dependence and efficacy, particularly enhancement of drug off-rates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. G. M. Lipkind, J. W. Kyle, and D. A. Hanck for advice and support, and A. Michels, G. Tonkovich, and R. Harris for technical assistance. Dr. R. J. French (Univ. of Calgary, Calgary, Canada) generously provided μ-conotoxin R13Q. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01-HL20592.

Abbreviations

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- WT

wild type

- μ1

adult rat skeletal muscle Na+ channel α-subunit

- rH1

rat cardiac Na+ channel α-subunit

- MTSEA

methanethiosulfonate ethylammonium

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.030438797.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.030438797

References

- 1.Catterall W A. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:S15–S48. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fozzard H A, Hanck D A. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:887–926. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terlau H, Heinemann S H, Stühmer W, Pusch M, Conti F, Imoto K, Numa S. FEBS Lett. 1991;293:93–96. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lipkind G M, Fozzard H A. Biophys J. 1994;66:1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80746-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiamvimonvat N, Pérez-García M T, Ranjan R, Marban E, Tomaselli G F. Neuron. 1996;16:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pérez-García M T, Chiamvimonvat N, Marban E, Tomaselli G F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guy H R, Seetharamulu P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:508–512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldin A L. In: Handbook of Receptors and Channels. Ligand- and Voltage-Gated Ion Channels. North R A, editor. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1995. pp. 73–112. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen C J, Bean B P, Colatsky T J, Tsien R W. J Gen Physiol. 1981;78:383–411. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.4.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frelin C, Cognard C, Vigne P, Lazdunski M. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986;122:245–250. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satin J, Kyle J W, Chen M, Bell P, Cribbs L L, Fozzard H A, Rogart R B. Science. 1992;256:1202–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backx P H, Yue D T, Lawrence J H, Marban E, Tomaselli G F. Science. 1992;257:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1321496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heinemann S H, Terlau H, Imoto K. Pflügers Arch. 1992;422:90–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00381519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L-Q, Chahine M, Kallen R G, Barchi R L, Horn R. FEBS Lett. 1992;309:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80783-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ragsdale D S, McPhee J C, Scheuer T, Catterall W A. Science. 1994;265:1724–1728. doi: 10.1126/science.8085162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qu Y, Rogers J, Tanada T, Scheuer T, Catterall W A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11839–11843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ragsdale D S, McPhee J C, Scheuer T, Catterall W A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9270–9275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright S N, Wang S Y, Kallen R G, Wang G K. Biophys J. 1997;73:779–788. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78110-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frazier D T, Narahashi T, Yamada M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;171:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strichartz G R. J Gen Physiol. 1973;62:37–57. doi: 10.1085/jgp.62.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alpert L A, Fozzard H A, Hanck D A, Makielski J C. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H79–H84. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2nd Ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1992. pp. 337–422. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinemann S H, Terlau H, Stühmer W, Imoto K, Numa S. Nature (London) 1992;356:441–443. doi: 10.1038/356441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Favre I, Moczydlowski E, Schild L. Biophys J. 1996;71:3110–3125. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79505-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schild L, Moczydlowski E. Biophys J. 1991;59:523–537. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82269-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bénitah J-P, Ranjan R, Yamagishi T, Janecki M, Tomaselli G F, Marban E. Biophys J. 1997;73:603–613. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sunami A, Dudley S C, Fozzard H A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14126–14131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trimmer J S, Cooperman S S, Tomiko S A, Zhou J Y, Crean S M, Boyle M B, Kallen R G, Sheng Z H, Barchi R L, Sigworth F J, et al. Neuron. 1989;3:33–49. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cribbs L L, Satin J, Fozzard H A, Rogart R B. FEBS Lett. 1990;275:195–200. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81470-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White M M, Chen L Q, Kleinfield R, Kallen R G, Barchi R L. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dudley S C, Todt H, Lipkind G, Fozzard H A. Biophys J. 1995;69:1657–1665. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chang N S, French R J, Lipkind G M, Fozzard H A, Dudley S. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4407–4419. doi: 10.1021/bi9724927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle D A, Cabral J M, Pfuetzner R A, Kuo A, Gulbis J M, Cohen S L, Chait B T, MacKinnon R. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cahalan M D, Almers W. Biophys J. 1979;27:39–56. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gellens M E, George A L, Chen L, Chahine M, Horn R, Barchi R L, Kallen R G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:554–558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumgarten C M, Dudley S C, Rogart R B, Fozzard H A. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C1356–C1363. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.6.C1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]