Abstract

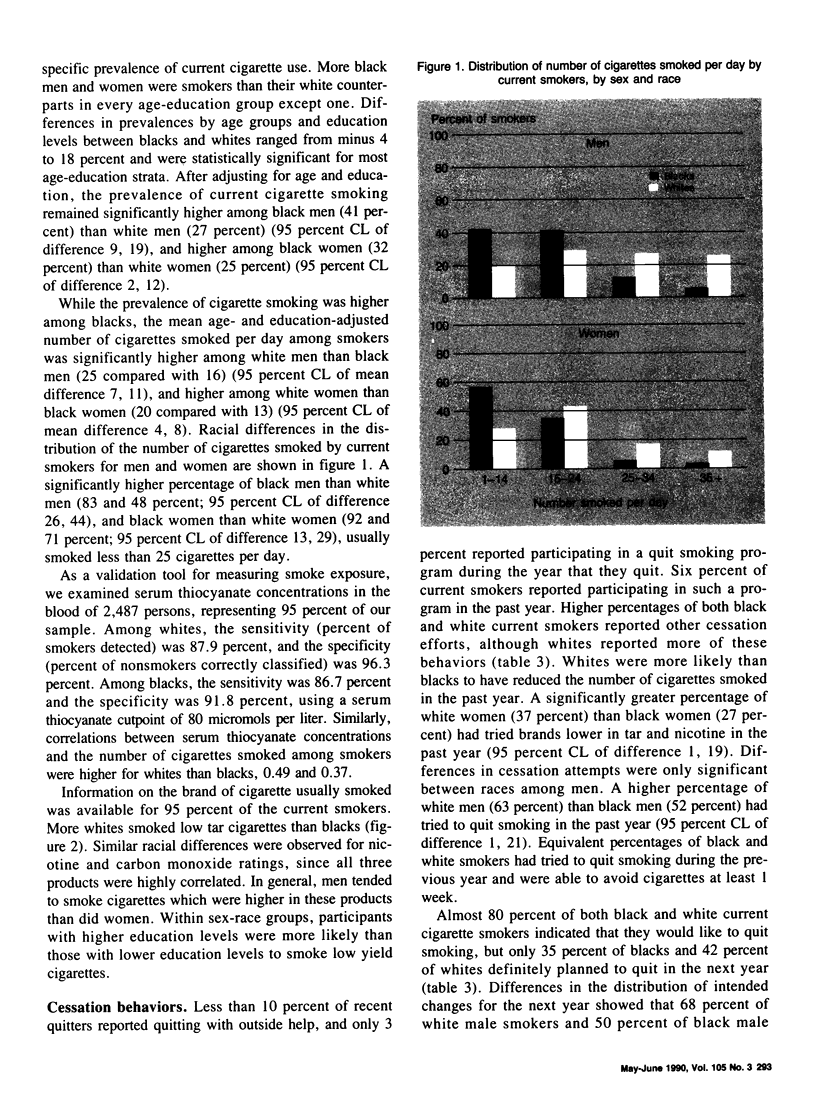

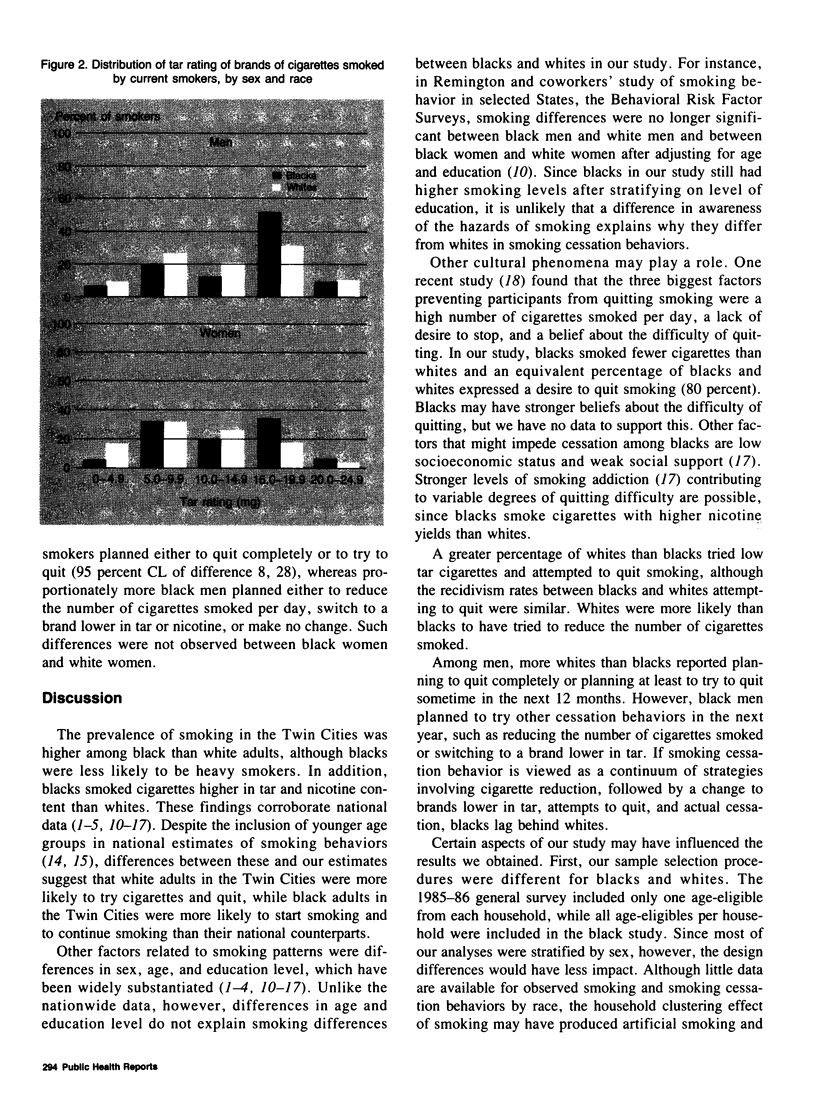

Smoking behaviors among blacks and whites were studied in a population-based sample of 2,626 residents of Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN. More blacks than whites were found to be smokers, before and after adjusting for age and education differences. More whites than blacks were former smokers, but the prevalence of those who had never smoked was comparable for whites and blacks. Among smokers, the mean number of cigarettes smoked per day was lower among blacks than whites, but more blacks were found to smoke cigarettes with high "tar" (dry particulate matter) and nicotine content. Men smokers were found to smoke more than women smokers, young people smoked more than older people, and those with a high school education or less smoked more than those with more than a high school education. Smoking cessation behavior consisted mostly of a variety of strategies that began with reducing cigarette consumption, followed by changing to lower tar brands, attempting to quit, and actually quitting. In general, a higher percentage of whites than blacks reported smoking cessation behaviors. A greater percentage of white than black women had tried cigarette brands lower in tar and nicotine within the previous year. Among men, a lower percentage of black than white smokers had tried quitting, and fewer black men planned to quit in the future. Blacks appeared to lag behind whites in their efforts to quit smoking. Smoking behavior continues to be problematic for both blacks and whites. Studies are needed to explain better the racial differences in smoking and smoking cessation behaviors, and to facilitate programs to encourage cessation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Butts W. C., Kueheman M., Widdowson G. M. Automated method for determining serum thiocyanate, to distinguish smokers from nonsmokers. Clin Chem. 1974 Oct;20(10):1344–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. C., Novotny T. E., Pierce J. P., Hatziandreu E. J., Patel K. M., Davis R. M. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. The changing influence of gender and race. JAMA. 1989 Jan 6;261(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartside P. S., Khoury P., Glueck C. J. Determinants of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in blacks and whites: the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am Heart J. 1984 Sep;108(3 Pt 2):641–653. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90649-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum R. F., Grant C. T. Coronary heart disease in black populations. II. Risk factors. Am Heart J. 1982 Oct;104(4 Pt 1):852–864. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatziandreu E. J., Pierce J. P., Fiore M. C., Grise V., Novotny T. E., Davis R. M. The reliability of self-reported cigarette consumption in the United States. Am J Public Health. 1989 Aug;79(8):1020–1023. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.8.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirscht J. P., Brock B. M., Hawthorne V. M. Cigarette smoking and changes in smoking among a cohort of Michigan adults, 1980-82. Am J Public Health. 1987 Apr;77(4):501–502. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti D. B., Friedman G. D., Kahn W. Accuracy of information on smoking habits provided on self-administered research questionnaires. Am J Public Health. 1981 Mar;71(3):308–311. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.3.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J. P., Fiore M. C., Novotny T. E., Hatziandreu E. J., Davis R. M. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. Educational differences are increasing. JAMA. 1989 Jan 6;261(1):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce J. P., Fiore M. C., Novotny T. E., Hatziandreu E. J., Davis R. M. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. Projections to the year 2000. JAMA. 1989 Jan 6;261(1):61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington P. L., Forman M. R., Gentry E. M., Marks J. S., Hogelin G. C., Trowbridge F. L. Current smoking trends in the United States. The 1981-1983 behavioral risk factor surveys. JAMA. 1985 May 24;253(20):2975–2978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland M. L., Fulwood R. Coronary heart disease risk factor trends in blacks between the first and second National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, United States, 1971-1980. Am Heart J. 1984 Sep;108(3 Pt 2):771–779. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn C. A. Health habits of U.S. adults, 1985: the "Alameda 7" revisited. Public Health Rep. 1986 Nov-Dec;101(6):571–580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprafka J. M., Folsom A. R., Burke G. L., Edlavitch S. A. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in blacks and whites: the Minnesota Heart Survey. Am J Public Health. 1988 Dec;78(12):1546–1549. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.12.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]