Abstract

The receptor subtype and mechanisms underlying relaxation to adenosine were examined in human isolated small coronary arteries contracted with the thromboxane A2 mimetic, 1,5,5-hydroxy-11α, 9α-(epoxymethano)prosta-5Z, 13E-dienoic acid (U46619) to approximately 50% of their maximum contraction to K+ (125 mM) depolarization (Fmax). Relaxations were normalized as percentages of the 50% Fmax contraction.

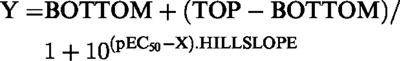

Adenosine caused concentration-dependent relaxations (pEC50, 5.95±0.20; maximum relaxation (Rmax), 96.7±1.4%) that were unaffected by either combined treatment with the nitric oxide inhibitors, NG-nitro-L-arginine (L-NOARG; 100 μM) and oxyhaemoglobin (HbO; 20 μM) or the ATP-dependent K+ channel (KATP) inhibitor, glibenclamide (10 μM). The pEC50 but not Rmax to adenosine was significantly reduced by high extracellular K+ (30 mM). Relaxations to the adenylate cyclase activator, forskolin, however, were unaffected by high K+ (30 mM).

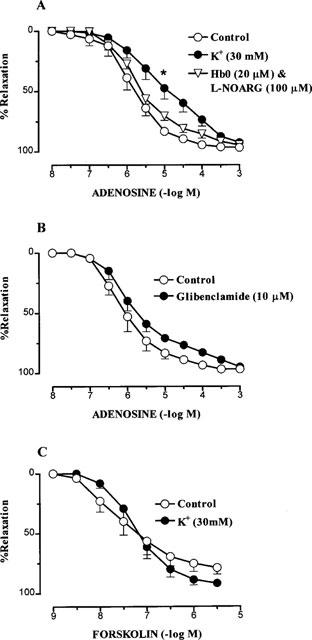

Adenosine and a range of adenosine analogues, adenosine, 2-chloroadenosine (2-CADO), 5′-N-ethyl-carboxamidoadenosine (NECA), R(−)-N6-(2-phenylisopropyl)-adenosine (R-PIA), S(+)-N6-(2-phenylisopropyl)-adenosine (S-PIA), N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), 1-deoxy-1-[6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamide (IB-MECA), 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine hydrochloride (CGS 21680), relaxed arteries with a rank order of potency of NECA=2-CADO>adenosine=IB-MECA=R-PIA= CPA>S-PIA)>CGS 21680.

Sensitivity but not Rmax to adenosine was significantly reduced approximately 80 and 20 fold by the non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist, 8-(p-sulphophenyl)theophylline (8-SPT) and the A2 receptor antagonist, 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX). By contrast, the A1-selective antagonist, 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX) had no effect on pEC50 or Rmax to adenosine.

These results suggest that A2B receptors mediate relaxation to adenosine in human small coronary arteries which is independent of NO but dependent in part on a K+-sensitive mechanism.

Keywords: Adenosine, A2B-purinoceptors, human coronary artery

Introduction

Adenosine is an endogenous vasodilator and is believed to play important roles in the regulation of coronary blood flow under normal physiological conditions and also during hypoxia and reperfusion after ischaemia (Berne, 1980; Collis & Hourani, 1993; Bouchard & Lamontagne, 1996; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997; Minamino et al., 1998). Whilst it is established that adenosine A2A receptors mediate vasodilatation to adenosine throughout the vasculature (Hussain et al., 1996; Belardinelli et al., 1996; Ongini & Fredholm, 1996; Conti et al., 1997; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997), less is known of the roles of A2B receptors. Thus, from limited functional studies, it remains controversial as to whether any vasodilator effects of A2B receptors are endothelium-dependent or -independent and mediated by nitric oxide (NO) or hyperpolarization, particularly via the opening of ATP-dependent K+ channels (KATP) (Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997). Furthermore, there is no information as to the identity of receptor subtypes underlying vasodilatation to adenosine in the human coronary vasculature, although both A2A and A2B receptors have been found on isolated human endothelial cells (Iwamoto et al., 1994; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997). Therefore, we investigated both the receptor type and the mechanisms involved in relaxation of human, resistance-like coronary arteries to adenosine in vitro. Our data demonstrate that A2B receptors mediate relaxation to adenosine in these clinically relevant arteries independent of nitric oxide (NO) and the endothelium but partly dependent upon the activation of non-KATP K+ channels.

Methods

Tissue source

Small coronary arteries were obtained from the discarded tip of the right atrial appendage from patients (64.4±1.7 years; 31 male, 12 female) undergoing mitral valve (one patient), aortic valve (four patients) or coronary bypass graft surgery (38 patients). Immediately following surgical removal, the atrial appendages were placed in cold, carboxygenated Krebs' solution and transported back to the laboratory. The segments of atrial appendage were viewed with a dissecting-light microscope under which the small coronary arteries were carefully freed of surrounding tissue.

Mounting of vessels in myograph

Coronary arteries were cut into 2 mm lengths and mounted horizontally on two parallel stainless steel wires (40 μm) in small vessel Mulvany-Halpern myographs (JP Trading, Denmark) to record changes in isometric force as previously described (Kemp & Cocks, 1997). Vessels were maintained in physiological Krebs' solution at 37°C and continuously gassed with carbogen (95% 02, 5% CO2). The Krebs' solution was composed of (in mM): Na+ 143.1, K+ 5.9, Ca2+ 2.5, Mg2+ 1.2, Cl− 128.7, HCO3− 25, SO42− 1.2, H2PO4− 1.2 and glucose 11, pH 7.4.

Normalization

After a 30 min equilibration period, vessel rings were maximally relaxed with sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10 μM), and then set to passive tensions equivalent to that required to produce 90% of their internal circumference when exposed to a transmural pressure of 100 mmHg (Kemp & Cocks, 1997). In brief, a passive length-tension curve was constructed for each vessel. From this curve, the effective transmural pressure was calculated and the vessel set at a tension equivalent to that generated at 0.9 times the diameter of the vessel at 100 mmHg (D100).

Experimental protocol

Following normalization, arteries were contracted with isotonic, high K+ Krebs' solution (124 mM KCl; KPSS) to determine their maximum levels of active force (Fmax; Kemp & Cocks, 1997). When the tissues reached Fmax, the bathing solution was replaced with normal Krebs' and the tissues allowed to return to their resting levels of passive force. Regardless of treatment, all arteries were then contracted to ∼50% Fmax with titrated concentrations of the thromboxane A2 mimetic, 1,5,5-hydroxy-11α, 9α-(epoxymethano)prosta-5Z, 13E-dienoic acid (U46619; 1–30 nM) and in some cases acetylcholine (ACh; 1–3 μM), which in this tissue only causes endothelium-independent contractions (Angus et al., 1991). Once these contractions reached steady plateaus, cumulative concentration-relaxation curves to adenosine, adenosine analogues or forskolin were constructed. All concentration-response curves were obtained in the presence of indomethacin (3 μM) to inhibit prostanoid synthesis and SNP (10 μM) to inhibit characteristic spontaneous contraction of these arteries since in preliminary studies we found relaxation to adenosine to be independent of NO. Furthermore, any masking of the vasodilator effects of endothelial adenosine receptors by SNP was unlikely since both endothelial A2A and A2B receptors are coupled via Gs to increase levels of cyclic AMP (Iwamoto et al., 1994). In a previous study examining endothelium- and NO-dependent relaxations to bradykinin in similar tissue, however, we used isoprenaline to control spontaneous activity and thus avoid such functional block of responses to endothelial NO (Kemp & Cocks, 1997). Thus, isoprenaline was substituted for SNP in the three experiments in which we examined the response to bradykinin in adjacent rings of artery used for the adenosine studies.

Responses to adenosine were obtained in the absence and presence of the NO inhibitors, NG-nitro-L-arginine (L-NOARG, 100 μM) and oxyhaemoglobin (HbO, 20 μM), high K+ (30 mM) isotonic Krebs' solution, the ATP-sensitive potassium channel (KATP) antagonist, glibenclamide (10 μM), and the adenosine receptor antagonist, 8-(p-sulphophenyl)theophylline (8-SPT, 100 μM), 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX, 100 μM) and 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentyl-xanthine (DPCPX, 10 nM). These antagonists were added 30 min prior to precontraction with U46619 and ACh. Forskolin relaxations were obtained in the absence and presence of high extracellular K+ (30 mM).

Drugs

U46619 ([1,5,5-hydroxy-11α, 9α-(epoxymethano)prosta-5Z, 13E-dienoic acid], Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI, U.S.A.); ACh, indomethacin, NG-nitro-L-arginine (L-NOARG), adenosine, bovine haemoglobin (Sigma, U.S.A.); 5′-N-ethyl-carboxamidoadenosine (NECA), 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl)phenethylamino-5′ N-ethylcarboxamido adenosine hydrochloride (CGS 21680), 2-chloroadenosine (2-CADO), 1-deoxy-1-[6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino] -9H -purin-9-yl]-N-methyl-β-D-ribofuranuronamide (IB-MECA), R(−)-N6-(2-phenylisopropyl)-adenosine (R-PIA), S(+)-N6-(2-phenylisopropyl)-adenosine (S-PIA), N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), 8-(p-sulphophenyl)theophylline (8-SPT), 3,7-dimethyl-1-propargylxanthine (DMPX), 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX), forskolin (RBI, U.S.A.); bradykinin triacetate (Fluka, U.K.); sodium nitroprusside (DBL., Australia). Stock solutions of U46619 (1 mM) were made up in absolute ethanol, L-NOARG (100 mM) in 1 M NaHCO3, and indomethacin (100 mM) in 1 M Na2CO3. Adenosine, S-PIA, R-PIA, NECA, 2-CADO, CGS 21680, CPA and DPCPX were made up as stock solutions (100 mM) in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). Haemoglobin was dissolved in 0.9% NaCl to make up a 1 mM stock solution. The stock solution was subsequently reduced to oxyhaemoglobin (HbO) by the addition of a small amount (<0.1 g) of sodium dithionite. Excess sodium dithionite was extracted by running the solution through a sephadex (PD-10) column equilibrated with 0.9% NaCl. All subsequent dilutions of stock solutions were in distilled water and all other drugs were made up in distilled water.

Statistical analysis

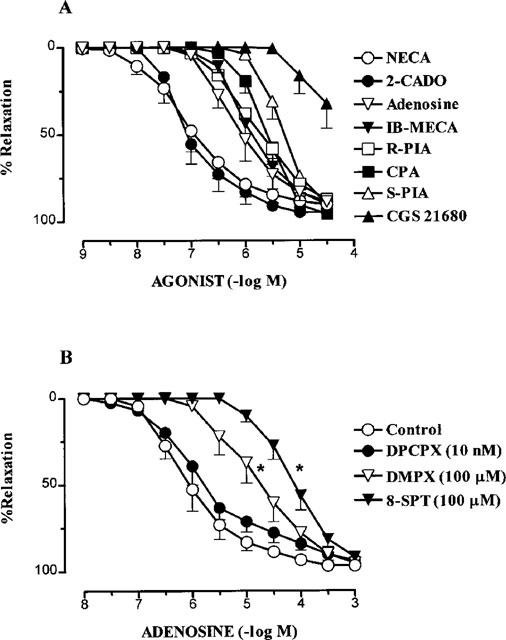

Responses were expressed as percentage reversal of the U46619 and ACh contraction (Kemp & Cocks, 1997). Contractile responses were measured as a percentage of the maximum contraction to KPSS (Fmax). The individual relaxation curves were fitted (Graphpad Prism, version 1.00) to the sigmoidal logistic equation,

|

where X=the logarithm of the agonist concentration and Y=the response. BOTTOM=the lower response plateau, TOP=the upper response plateau and pEC50 is the X value when the response is halfway between BOTTOM and TOP. The variable HILLSLOPE controls the slope of the curve. From this relationship, computer estimates of pEC50 values were determined and expressed as −log M.

Differences between mean pEC50 and maximum relaxation (Rmax) values were tested either with a two-tailed Student's unpaired t-test or one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with comparisons to control or between all experimental groups made via Dunnett's and Tukey's modified t-tests, respectively. Results are expressed as mean±s.e.mean and statistical significance was accepted at the P<0.05 level. n values refer to number of rings from separate patients.

Results

The effect of L-NOARG, HbO and high K+ on responses to adenosine

Adenosine caused concentration-dependent relaxations (Rmax; 96.7±1.4%, pEC50; 5.95±0.20) in small coronary arteries with diameters (D100) of 207.3±6.2 μm (n=20). The response to adenosine was unaffected by a combination of HbO (20 μM) and L-NOARG (100 μM) (Figure 1). By contrast, in separate arteries from the same patients, endothelium-dependent relaxation to bradykinin, as we previously reported (Kemp & Cocks, 1997), was markedly attenuated by this treatment (n=3, data not shown). Raising the extracellular concentration of K+ to 30 mM, however, caused a significant 12 fold (P<0.05) decrease in the sensitivity (pEC50; 4.88±0.32, n=4) to adenosine with no change in Rmax (92.5±2.1%, n=4) (Figure 1). Glibenclamide (10 μM) had no effect on either the sensitivity (pEC50, 6.07±0.21, n=5) or Rmax; (92.5±2.1%, n=5) to adenosine (Figure 1) and relaxations to forskolin (pEC50; 7.43±0.22, Rmax, 79.7±5.1%, n=4) were unchanged in the presence of high K+ (30 mM; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relaxations in human isolated small coronary arteries to (A) adenosine in normal Krebs' (control), high K+ (30 mM KCl) and a combination of oxyhaemoglobin (HbO) and L-NOARG (n=4–5), (B) adenosine in the presence of normal Krebs' (control, n=5) or glibenclamide (n=5) and (C) forskolin in normal Krebs' (control, n=4) and high K+ (n=4). Values are mean±s.e.mean. (*) indicates pEC50 value significantly different from control (P<0.05, Dunnett's modified t-statistic).

Responses to adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists

All the adenosine analogues used caused concentration-dependent relaxation in human small coronary arteries with a rank order of potency (pEC50 values in parentheses; n=4–5) of NECA (6.98±0.20)=2-CADO (6.98±0.20)>adenosine (6.07±0.21)=IB-MECA (5.93±0.09)=R-PIA (5.72±0.10) =CPA (5.63±0.09)>S-PIA (5.27±0.09)>CGS 21680 (<5.00) (Figure 2). All analogues caused near maximal relaxation except CGS 21680 (30 μM) which reversed the level of contraction by 32.3±14.3%.

Figure 2.

Relaxations to (A) the adenosine agonists; NECA, 2-CADO, adenosine, IB-MECA, R-PIA, CPA, S-PIA and CGS 21680 (n=4–5) and (B) adenosine in the absence (control) and presence of the adenosine antagonists, DPCPX, DMPX and 8-SPT (n=4–5) in human isolated small coronary arteries. Values are mean±s.e.mean. (*) indicates pEC50 value significantly different from control (P<0.01, Dunnett's modified t-statistic).

The response to adenosine was unchanged in the presence of the selective A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, DPCPX (10 nM) (pEC50, 5.89±0.21; Rmax; 94.0±1.9%, n=4; Figure 2). By contrast, the A2 adenosine receptor antagonist, DMPX (100 μM), and the non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist, 8-SPT (100 μM), caused significant 20 (P<0.01) and 80 fold (P<0.01) decreases respectively in the sensitivity to adenosine, with no change in Rmax (Figure 2).

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate that adenosine mediates relaxation of human small isolated coronary arteries via A2B receptors. Furthermore, the response to adenosine in these clinically important arteries appeared to be independent of NO and thus the endothelium, but partly mediated by a K+-sensitive mechanism.

Four subtypes of adenosine receptors, A1, A2A, A2B and A3 have been cloned (Collis & Hourani, 1993; Tucker & Linden, 1993; Burnstock, 1995; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997) and adenosine and its analogues display characteristic orders of potencies at each of these receptors. In the present study, the adenosine analogue, NECA, was significantly more potent than both CPA and R-PIA suggesting that A2 rather than A1 receptors were involved (Collis & Hourani, 1993). Also, the >100 fold higher potency of NECA compared with CGS 21680 indicated the presence of A2B rather than A2A receptors since these agonists are equipotent at A2A receptors (Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997). Thus, the rank order of potency of adenosine and its analogues in the present study was NECA=2-CADO>adenosine=IB-MECA=R-PIA= CPA>S-PIA>CGS 21680, which is characteristic of A2B receptors (Collis & Hourani, 1993; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997). Furthermore, the potency ratios relative to NECA for NECA, adenosine, CPA, R-PIA, S-PIA and CGS21680 observed here were 1, 0.15, 0.06, 0.07, 0.02 and <0.01 respectively. These compare favourably with values from two separate studies with similar adenosine analogues at A2B receptors in the guinea-pig aorta. Thus, Martin (1992) found values of 1, 0.16, 0.03, and <0.001 for NECA, adenosine, R-PIA and CGS21860 respectively, whilst in the same tissue, Gurden et al. (1993) reported values of 1, 0.03, 0.03, 0.003 and 0.002 for NECA, CPA, R-PIA, S-PIA and CGS21860 respectively.

It is unlikely that A3 receptors mediated the response to adenosine (Hannon et al., 1995) in the human small coronary artery given the low potency of the A3-selective agonist, IB-MECA, compared with its affinity of 1 nM at rat A3 receptors (Jacobson et al., 1995) and A3 receptors are resistant to inhibition by the A1, A2 non-selective antagonist, 8-SPT (10 μM; Hannon et al., 1995). 8-SPT, however, antagonized the response to adenosine with an estimated affinity of 5.9 which is similar to that reported for 8-SPT at A2B receptors in the guinea-pig aorta (pKB=5.3; Hargreaves et al., 1991). Furthermore, the A2 antagonist, DMPX, inhibited the relaxation curve to adenosine in an apparent competitive manner yet in contrast the selective A1 antagonist, DPCPX, failed to have any effect. Therefore, our findings indicate that A2B receptors mediate relaxation to adenosine in human small coronary arteries. This is in contrast to substantial published literature which demonstrates that adenosine mediates most of its vasodilator responses via A2A receptors (Ongini & Fredholm, 1996; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997; Shryock & Belardinelli, 1997). For example, A2A receptors appear to mediate relaxation to adenosine in large coronary arteries of the pig (Conti et al., 1997), cow (Conti et al., 1993) and vasodilation in the isolated perfused guinea-pig heart (Vials & Burnstock, 1993; Poucher et al., 1995; Belardinelli et al., 1996, 1998; Shryock et al., 1998). Also, although an undefined A2 receptor has been reported in human large coronary arteries, it was not further subtyped as either A2A or A2B (Ramagopal et al., 1988).

In the present study, we confirmed our earlier finding in similar human small coronary arteries that endothelium-dependent relaxation to bradykinin was largely blocked by combined L-NOARG and HbO treatment (Kemp & Cocks, 1997). Therefore, the inability of the same NO inhibitors to block relaxation to adenosine in adjacent, similar-sized arteries suggests that adenosine did not mediate its effect via either NO or the endothelium. Also, it was unlikely that any endothelial A2A-mediated responses were masked by functional antagonism caused by the presence of SNP to inhibit spontaneous activity since CGS 21680 was still virtually inactive in tissues treated with isoprenaline instead of SNP to control spontaneous activity (Kemp & Cocks, unpublished data). Similar endothelium-independent vasodilator responses to adenosine in the rat mesenteric bed as those described here have also been reported to be mediated by A2B receptors (Rubino et al., 1995). The direct smooth muscle relaxing effect of adenosine, however, appeared to involve K+ channels and thus a hyperpolarization-dependent mechanism given that it was partially inhibited by high extracellular K+. In coronary vascular preparations where KATP have been implicated in relaxation to adenosine via hyperpolarization (Randall, 1995; Bouchard & Lamontagne, 1996; Nakae et al., 1996; Mutafovayambolieva & Keef, 1997), the opening of these channels is thought to be regulated by changes in intracellular levels of cyclic AMP (Miyoshi & Nakaya, 1993; Kleppisch & Nelson, 1995; Feoktistov & Biaggioni, 1997). Our data, however, indicate that cyclic AMP-regulated KATP do not underlie relaxation to adenosine in the human small coronary arteries since the response was refractory to glibenclamide and relaxation to forskolin was unaffected by high extracellular K+. A role for other K+ channels such as inward rectifying (KIV), voltage-dependent (KV) and Ca2+-activated K+ channels (KCa), however, cannot be excluded since Cabell et al. (1994) found that tetraethylammonium (TEA) and the more selective inhibitor of large-conductance KCa, iberiotoxin, blocked adenosine-induced relaxation in canine coronary arteries. Thus, adenosine may cause smooth muscle relaxation, in part, via the opening of KCa channels as has been reported in large coronary arteries of the pig and human (Olanrewaju et al., 1995) and small coronary arteries of the dog (Cabell et al., 1994).

In conclusion, the present study provides strong circumstantial evidence that relaxation of human small resistance-like coronary arteries by adenosine is mediated by A2B receptors which are coupled to K+ channels to mediate part of the response. A more definitive demonstration that A2B receptors mediate coronary vasodilatation to adenosine in humans, however, awaits the development of selective A2B receptor antagonists.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by project grants from the NMHRC and National Heart Foundation of Australia. We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Mrs Janet Rogers and the cooperation and assistance of all members of the Alfred Hospital Cardiothoracic Surgical Unit.

Abbreviations

- ACh

- A1

- A2A

- A2B

- A3

- ANOVA

- 2-CADO

- CGS 21680

- CPA

- D100 DMPX

- DMSO

- DPCPX

- Fmax

- Hb0

- IB-MECA

- KATP

- KCa

- KIV

- KV

- KPSS

- L-NOARG

- NECA

- pEC50

- pKB

- Rmax

- R-PIA

- SNP

- S-PIA

- 8-SPT

- TEA

- U46619

References

- ANGUS J.A., COCKS T.M., MCPHERSON G.A., BROUGHTON A. The acetylcholine paradox: a constrictor in human small coronary arteries even in the presence of endothelium. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1991;18:33–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1991.tb01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELARDINELLI L., SHRYOCK J.C., RUBLE J., MONOPOLI A., DIONISOTTI S., ONGINI E., DENNIS D.M., BAKER S.P. Binding of the novel nonxanthine A2A adenosine receptor antagonist H3- SCH58261 to coronary artery membranes. Circ. Res. 1996;79:1153–1160. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELARDINELLI L., SHRYOCK J.C., SNOWDY S., ZHANG Y., MONOPOLI A., LOZZA G., ONGINI E., OLSSON R.A., DENNIS D.M. The A2A adenosine receptor mediates coronary vasodilatation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;284:1066–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNE R.M. The role of adenosine in the regulation of coronary blood flow. Circ. Res. 1980;47:807–813. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOUCHARD J.F., LAMONTAGNE D. Mechanisms of protection afforded by preconditioning to endothelial function against ischemic injury. Am. J. Physiol., - Heart Circ. Physiol. 1996;40:H1801–H1806. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.5.H1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNSTOCK G. Current state of purinoceptor research. Pharmaceutica Acta Helvetiae. 1995;69:231–242. doi: 10.1016/0031-6865(94)00043-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CABELL F., WEISS D.S., PRICE J.M. Inhibition of adenosine-induced coronary vasodilation by block of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Am. J. Physiol - Heart Circ. Physiol. 1994;36:H1455–H1460. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLIS M.G., HOURANI S.M.O. Adenosine receptor subtypes. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;14:360–366. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONTI A., LOZZA G., MONOPOLI A. Prolonged exposure to 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA) does not affect the adenosine A2A-mediated vasodilation in porcine coronary arteries. Pharmacol. Res. 1997;35:123–128. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1996.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONTI A., MONOPOLI A., GAMBA M., BOREA P.A., ONGINI E. Effects of selective A1 and A2 adenosine receptor agonists on cardiovascular tissues. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1993;348:108–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00168545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEOKTISTOV I., BIAGGIONI I. Adenosine A2B receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 1997;49:381–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GURDEN M.F., COATES J., ELLIS F., EVANS B., FOSTER M., HORNBY E., KENNEDY I., MARTIN D.P., SRONG P., VARDEY C.J., WHEELDON A. Functional Characterisation of three adenosine receptor types. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:693–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNON J.P., PFANNKUCHE H.J., FOZARD J.R. A role for mast cells in adenosine A3 receptor-mediated hypotension in the rat. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:945–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARGREAVES M.B., STOGGALL S.M., COLLIS M.G. Evidence that the adenosine receptor mediating relaxation in dog lateral saphenous vein and guinea-pig aorta is of the A2B subtype. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1991;102:198P. [Google Scholar]

- HUSSAIN T., LINDEN J., MUSTAFA S.J. I125-APE binding to adenosine receptors in coronary artery - photoaffinity labelling with I125-azidoAPE. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;276:284–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IWAMOTO T., UMEMURA S., TOYA Y., UCHIBORI T., KOGI K., TAKAGI N., ISHII M. Identification of adenosine A2 receptor cAMP system in human aortic endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;199:905–910. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JACOBSON K.A., KIM H.O., SIDDIQI S.M., OLAH M.E., STILES G.L., VON LUBITZ D.K.J.E. A3-adenosine receptors: design of selective ligands and therapeutic prospects. Drugs of the Future. 1995;20:689–699. doi: 10.1358/dof.1995.020.07.531583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEMP B.K., COCKS T.M. Evidence that mechanisms dependent and independent of nitric oxide mediate endothelium-dependent relaxation to bradykinin in human small resistance-like coronary artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:757–762. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEEPISCH T., NELSON M.T. Adenosine activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in arterial myocytes via A2 receptors and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:12441–12445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN P.L. Relative agonist potencies of C2-substituted analogues of adenosine; evidence for adenosine A2B receptors in the guinea-pig aorta. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;216:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90365-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINAMINO T., KITAKAZE M., MATSUMURA Y., NISHIDA K., KATO Y., HASHIMURA K., MATSUURA Y., FUNAYA H., SATO H., KUZUYA T., HORI M. Impact of coronary risk factors on contribution of nitric oxide and adenosine to metabolic coronary vasodilation in humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1998;31:1274–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYOSHI H., NAKAYA Y. Activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase in cultured smooth muscle cells of porcine coronary artery. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;193:240–247. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUTAFOVAYAMBOLIEVA V.N., KEEF K.D. Adenosine-induced hyperpolarization in guinea-pig coronary artery involves A2B receptors and KATP channels. Am. J. Physiol. - Heart Circulatory Physiol. 1997;42:H2687–H2695. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.6.H2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAE I., TAKAHASHI M., TAKAOKA A., LIU Q., MATSUMOTO T., AMANO M., SEKINE A., NAKAJIMA H., KINOSHITA M. Coronary effects of diadenosine tetraphosphate resemble those of adenosine in anesthetized pigs - involvement of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. J. Cardiovascular Pharmacol. 1996;28:124–133. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199607000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLANREWAJU H.A., HARGITTAI P.T., LIEBERMAN E.A., MUSTAFA S.J. Role of endothelium in hyperpolarization of coronary smooth muscle by adenosine and its analogues. J. Cardiovasc. Pharm. 1995;25:234–239. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONGINI E., FREDHOLM B.B. Pharmacology of adenosine A2A receptors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996;17:364–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POUCHER S.M., KEDDIE J.R., SINGH P., STOGGALL S.M., CAULKETT P.W.R., JONES G., COLLIS M.G. The in vitro pharmacology of ZM 241385, a potent, non-xanthine, A2A selective adenosine receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:1096–1102. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAMAGOPAL M.V., CHITWOOD R.W., MUSTAFA S.J. Evidence for an A2 adenosine receptor in human coronary arteries. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1988;151:483–486. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANDALL M.D. The involvement of ATP-sensitive potassium channels and adenosine in the regulation of coronary flow in the isolated perfused rat heart. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:3068–3074. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBINO A., RALEVIC V., BURNSTOCK G. Contribution of P1-(A2b subtype) and P2-purinoceptors to the control of vascular tone in the rat isolated mesenteric arterial bed. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:648–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHRYOCK J.C., BELARDINELLI L. Adenosine and adenosine receptors in the cardiovascular system - biochemistry, physiology and pharmacology. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997;79:2–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHRYOCK J.C., SNOWDY S., BARALDI P.G., CACCIARCI B., SPALLUTO G., MONOPOLI A., ONGINI E., BAKER S.P., BELARDINELLI L. A2A-adenosine receptor reserve for coronary vasodilatation. Circulation. 1988;98:711–718. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TUCKER A.L., LINDEN J. Cloned receptors and cardiovascular responses to adenosine. Cardiovasc. Res. 1993;27:62–67. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VIALS S., BURNSTOCK G. A2-purinoceptor-mediated relaxation in the guinea-pig coronary vasculature: a role for nitric oxide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;109:424–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]