Abstract

Ebola virions contain a surface transmembrane glycoprotein (GP) that is responsible for binding to target cells and subsequent fusion of the viral and host-cell membranes. GP is expressed as a single-chain precursor that is posttranslationally processed into the disulfide-linked fragments GP1 and GP2. The GP2 subunit is thought to mediate membrane fusion. A soluble fragment of the GP2 ectodomain, lacking the fusion-peptide region and the transmembrane helix, folds into a stable, highly helical structure in aqueous solution. Limited proteolysis studies identify a stable core of the GP2 ectodomain. This 74-residue core, denoted Ebo-74, was crystallized, and its x-ray structure was determined at 1.9-Å resolution. Ebo-74 forms a trimer in which a long, central three-stranded coiled coil is surrounded by shorter C-terminal helices that are packed in an antiparallel orientation into hydrophobic grooves on the surface of the coiled coil. Our results confirm the previously anticipated structural similarity between the Ebola GP2 ectodomain and the core of the transmembrane subunit from oncogenic retroviruses. The Ebo-74 structure likely represents the fusion-active conformation of the protein, and its overall architecture resembles several other viral membrane-fusion proteins, including those from HIV and influenza.

Keywords: x-ray crystallography, membrane fusion, filovirus, oncogenic retroviruses

Ebola viruses are nonsegmented, negative-strand RNA viruses, which, together with Marburg viruses, constitute the family Filoviridae (1). The most pathogenic subtype (Zaire) of Ebola virus causes a severe form of hemorrhagic fever in humans and nonhuman primates (2–4). Recent work suggests that infection of endothelial cells by Ebola virus contributes to the hemorrhagic components of the disease (5). However, the natural hosts for Ebola viruses have not yet been identified, and thus the factors that influence the evolution and ecology of these viruses, and lead to human infections, remain largely unknown.

Ebola virions possess a single surface transmembrane glycoprotein (GP) that plays a central role in entry into target cells by binding to as yet unidentified receptors, and then mediating fusion between the viral and the host cell membranes. The four known subtypes of Ebola virus (Zaire, Sudan, Reston, and Ivory Coast) demonstrate 51–63% sequence identity between GPs and 45% identity with Marburg virus (6). GP is expressed as a single chain precursor of 676 aa that is posttranslationally processed into the disulfide-linked fragments GP1 and GP2 (Fig. 1) by a cellular convertase, furin (7).

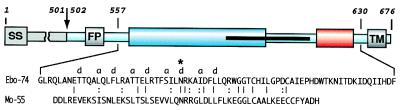

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of Ebola GP. The residues are numbered according to their position in the Ebola GP sequence (Zaire subtype; Genbank accession no. U23187). The sequence of Ebo-74 is indicated. Ebola GP is proteolytically processed into the receptor binding domain GP1 (residues 33–501; gray), and the transmembrane domain GP2 (residues 502–676; light blue). Close to the N terminus, GP2 contains the fusion peptide (FP, residues 524–539). Two regions predicted to form amphipatic helical regions are indicated (blue and red). GP2 is presumed to be disulfide-linked to GP1 through Cys-609. The C-terminal part of the first helical region and most of the loop correspond to an immunosupressive motif in oncogenic retroviruses (residues 584–610; black stripe). The transmembrane anchor (TM, residues 651–672) attaches GP2 to the viral membrane. Identical residues between the sequences of Ebo-74 and Mo-55 from Mo-MLV (10, 12) are indicated with lines, and similar residues are indicated with dots. The chloride-binding residue, Asn-586, is marked by ∗. SS; signal sequence.

Ebola GP shares general features with many other viral membrane fusion proteins. Analogous to the Ebola GP1 and GP2 subunits, respectively, are the HA1 and HA2 subunits from influenza, and the surface subunit and transmembrane subunit (TM) from retroviruses, including gp120 and gp41 from HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). In each instance, the first subunit is responsible for binding to cell-surface receptors, whereas the second subunit is responsible for mediating membrane fusion (8).

The GP2 subunit of Ebola contains several characteristic features (Fig. 1). Toward its N terminus is the “fusion-peptide” region, which is thought to insert directly into the target membrane at an early stage in the membrane-fusion process. After the fusion peptide is a region containing 4,3 hydrophobic (heptad) repeats, a sequence motif suggestive of coiled-coil structures. Next is a disulfide-bonded loop region that is homologous to the conserved “immunosuppressive” motif found in oncogenic retroviruses (9), followed by another region predicted to form an amphipathic helix. A transmembrane helix is found at the C terminus of GP2, but there is no substantial intra-viral domain. Several of these features of the Ebola GP2 subunit also can be found in the TM of the envelope proteins of oncogenic retroviruses, such as Moloney murine leukemia virus (Mo-MLV) and Rous sarcoma virus (10, 11).

Previously, we used a protein-dissection strategy to identify and determine the x-ray structures of protease-resistant cores for viral proteins involved in membrane fusion, including those from Mo-MLV (10, 12), HIV-1 (13, 14), and SIV (15, 16). In this approach, we first construct a recombinant model for the ectodomain (i.e., the extra-viral region). The hydrophobic fusion peptide is not included, as this region is expected to interfere with biophysical and structural characterization. Next, limited proteolysis experiments are used to identify a soluble core of the ectodomain that then can be characterized by structural methods.

Here, we used the same approach to investigate the structure of the GP2 ectodomain from Ebola virus. We produced a 95-aa residue fragment of GP2, corresponding to the ectodomain without the amino-terminal fusion-peptide region. After establishing the correct disulfide connectivity in the region of the fragment that corresponds to the retroviral immunosuppressive motif (by characterizing disulfide variants of the ectodomain), limited proteolysis experiments were used to identify a proteolytically resistant core of the ectodomain. This 74-aa core (referred to as Ebo-74) was crystallized, and the x-ray crystal structure was determined at 1.9-Å resolution.

While our crystal structure was being refined, the structure of a similar fragment of Ebola GP2, fused to a trimeric coiled coil, was reported at 3.0-Å resolution (17). Our results are in overall agreement with the structure of this fusion protein (17), and they confirm the remarkable structural similarity between the core of the Ebola GP2 protein and the x-ray crystal structure of the corresponding core from the Mo-MLV TM protein that had been anticipated earlier (10).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene Construction and Protein Purification.

By using optimal codons for Escherichia coli expression (18), a synthetic gene was constructed that encodes residues 549–643 (i.e., Ebo-95) of the Ebola virus GP (Zaire subtype; Genbank accession no. U23187) (6). To avoid nonspecific disulfide bond formation, Cys-556 was changed to an alanine residue. The constructed gene was inserted into the HindIII–BamHI restriction site of pMMHb (19). The resulting plasmid, denoted pMMHb-Ebo95, expresses a fusion protein containing a modified TrpLE leader sequence and a 9-histidine tag. Plasmids encoding additional single cysteine-to-alanine mutations, denoted pMMHb-Ebo95.1, pMMHb-Ebo95.2, and pMMHb-Ebo95.3, were generated by site-directed mutagenesis at Cys-601, Cys-608, and Cys-609, respectively. A truncated version of Ebo-95, denoted Ebo-74, was created by amplifying the nucleotides corresponding to residues 557–630 from the pMMHb-Ebo95.3 plasmid by using PCR. The amplified region was inserted into the HindIII–BamHI restriction site of pMMHb to generate a plasmid denoted pMMHb-Ebo74. The recombinant proteins were expressed and purified as described (19), except that the BL21 (DE3) pLysE strain of E. coli was used. Disulfide bonds were formed by air oxidation before CNBr cleavage. For purification on the Ni2+ column, the sample was applied in denaturing buffer containing 10 mM imidazole, as described (19), then washed with buffer containing 100 mM imidazole, and eluted with buffer containing 250 mM imidazole. Final purification was by reverse-phase HPLC using a Vydac C18 preparative column with a water/acetonitrile gradient of 0.1%/min in the presence of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The mass of each purified protein was verified by mass spectrometry on a Voyager Elite matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA), and in each case the observed mass was within 3 Da of the expected value.

Proteolysis.

All proteolysis reactions were performed with 1 mg/ml Ebo-95.3 and 0.1 mg/ml protease at room temperature and were quenched with 5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (final concentration). Subtilisin reactions were carried out in the presence of 20 mM Tris, 10 mM CaCl2, pH 8.0, while protease K reactions were performed in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.7. Proteolysis samples were analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC connected to a Finnigan-MAT (San Jose, CA) LCQ electrospray mass spectrometer. Fragments were assigned by matching observed masses with a list of possible fragment masses predicted by the computer program fragment mass (E. Wolf and P.S.K., http://www.wi.mit.edu/kim/computing.html). All assigned fragments were within 1 Da of their predicted values. In addition, the next closest predicted mass was never closer than 3 Da to the assigned mass and most differed by more than 5 Da.

CD Spectroscopy.

All CD spectroscopy was performed by using an Aviv 62 DS spectrometer (Aviv Associates, Lakewood, NJ) as described (13). All reported data were collected at a dynode voltage of less than 450 V. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Edelhoch (20). Thermal unfolding studies of the Ebo-95 variants were carried out with 5 μM protein in 100 mM NaPO4, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2. Thermal unfolding studies with Ebo-74 were carried out with 2.5 μM protein in 10 mM acetate, pH 4.5 with either no salt or 5 mM added salt (NaF, NaCl, or NaBr).

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Stocks of HPLC-purified Ebo-95.3 and Ebo-74 were dissolved in water, and their final protein concentrations were adjusted to 10 mg/ml. Although attempts to grow diffraction-quality crystals of Ebo-95.3 were unsuccessful, Ebo-74 crystallized under several conditions using crystallization kits I and II (Hampton Research, Riverside, CA) to produce similar-looking hexagonal bipyramids. These original crystals, however, possessed internal disorder as indicated by an uneven shape and poor diffraction. Well-diffracting crystals of Ebo-74 were grown via the hanging drop method by equilibrating 2-μl drops (protein solution mixed 1:1 with reservoir solution) against a reservoir solution containing 16–18% isopropanol, 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.6, and 100–200 mM CaCl2. Crystals grew as hexagonal bipyramids to a maximum size of 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.2 mm3 within 1–2 weeks. The crystals belong to the space group P62 (or P64, a = b = 75.66 Å, c = 67.94 Å, α = β = 90o, γ = 120o). Self-rotation function calculations and a 44% solvent content (21) in the crystals suggested one trimer in the asymmetric unit, wherein monomers are related by an approximate noncrystallographic three-fold axis.

For data collection, crystals were transferred to a drop containing reservoir solution plus 30–40% glycerol, harvested, and flash-frozen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K by using a Quantum-4 charge-coupled device detector and the 5.0.2 beam line at the Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA). The Ebo-74 crystal diffraction limits were improved, and the mosaicity was decreased significantly by a cryo-annealing technique in which the crystal was repeatedly thawed for about 30 sec by blocking the cryostream and then frozen again. An elevated concentration of cryoprotectant to prevent ice formation was essential with this technique. Diffraction intensities were integrated by using denzo and scalepack software (22) and reduced to structure factors with the program truncate from the CCP4 program suite (23). The structure of Ebo-74 was solved by molecular replacement by using the program amore (24). Solvent flattening, histogram matching, and three-fold noncrystallographic averaging with the program dm (25) improved phasing. Density interpretation and model building were done with the program o (26). Crystallographic refinement of the structure (Table 1) was done with the cns (27) and refmac (23) programs. Noncrystallographic symmetry restraints were not used in the final refinement.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Resolution, Å | 20.0–1.90 |

| Observed reflections | 86,630 |

| Unique reflections | 17,326 |

| Completeness, % | 98.9 (99.1)* |

| Rmerge† | 0.037 (0.309)* |

| Refinement | |

| Protein nonhydrogen atoms | 1,806 |

| Water molecules | 214 |

| Heteroatoms (Cl−) | 1 |

| Rcryst‡ | 0.205 (0.239)* |

| Rfree‡ | 0.269 (0.319)* |

| rms deviation from ideal geometry | |

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.009 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.3 |

| Dihedral angles, ° | 19.8 |

| Average B factor, Å2 | 40.6 |

Values in parentheses correspond to highest resolution shell 1.93 to 1.90 Å.

Rmerge = ΣΣj|Ij(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/Σ|〈I(hkl)〉|, where Ij is the intensity measurement for reflection j and 〈I〉 is the mean intensity over j reflections.

Rcryst (Rfree) = Σ∥Fobs(hkl)| − |Fcalc(hkl)∥/Σ|Fobs(hkl)|, where Fobs and Fcalc are observed and calculated structure factors, respectively. No σ-cutoff was applied. Ten percent of the reflections were excluded from refinement and used to calculate Rfree.

RESULTS

Stability of Ebo-95 Disulfide Bond Variants.

A 95-residue fragment, denoted Ebo-95, of the Ebola GP2 ectodomain was produced with a plasmid containing a synthetic gene encoding residues 549–643 from the Ebola Zaire GP (6). Cys-556 was changed to Ala in Ebo-95 to avoid nonspecific disulfide bond formation. Within the region of the protein with sequence similarity to the immunosuppressive-loop region of retroviral TM proteins, there are three other cysteine residues (Cys-601, Cys-608, and Cys-609). The disulfide connectivity for the analogous region in Mo-MLV, established previously by biochemical methods, is from the first to the second Cys residue in this region (12).

Although it seemed likely that the same disulfide connectivity exists in Ebola GP2, we sought to experimentally verify this similarity between the filovirus and retrovirus proteins. To generate proteins representing the three possible disulfide variants, each of the three cysteines was individually changed to alanine. Each variant was air-oxidized in the presence of 6 M GuHCl to ensure intramolecular disulfide bond formation. All three variants folded to form stable, highly helical structures (data not shown). The thermal stability of each variant was measured by CD studies. Comparable to the results of analogous experiments on Mo-MLV peptides (12), the Ebo-95 variant with a Cys-601 to Cys-608 disulfide bond (Ebo-95.3) is indeed the most stable (apparent Tm of 88°C, as compared with 78°C and 84°C for the variants with the Cys-608 to Cys-609, and Cys-601 to Cys-609 disulfide bonds, respectively; data not shown).

Identification of the Ebo-74 Core.

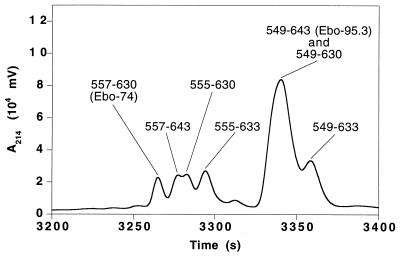

Ebo-95.3, the most stable disulfide variant, was subjected to proteolysis by subtilisin and protease K. Each protease removes residues from both the N and C termini of Ebo-95.3 molecules. Digestion with subtilisin results in two predominant fragments, corresponding to residues 555–633 (79 residues) or residues 555–630 (76 residues) from the full-length Ebola GP (data not shown). These fragments represent a seven-residue truncation from the N terminus and either a 10- or 13-residue truncation from the C terminus. Digestion with protease K (Fig. 2) results in these same fragments, but it also generates a slightly shorter 74-residue fragment corresponding to residues 557–630 of Ebola GP. This fragment, denoted Ebo-74, was chosen for detailed study as the core of the Ebola GP2 ectodomain.

Figure 2.

Protein dissection of the Ebola GP2 ectodomain. Shown is a portion of a reverse-phase HPLC chromatogram of a sample of Ebo-95.3 digested with protease K for 2 hr in 20 mM Tris, pH 8.7. The HPLC eluant was analyzed directly with an on-line mass spectrometer (Finnigan-MAT LCQ), and the fragments (indicated with residue numbers) were assigned by matching observed masses with a list of all possible predicted fragment masses (see text). Fragments corresponding to peptides described in this paper are labeled with parentheses.

Solution Properties of Ebo-74.

CD spectroscopy indicates that Ebo-74 (with the 601–608 disulfide bond) folds into a stable helical structure ([θ]222 = −23, 200 deg·cm2⋅dmol−1, or ≈50 helical residues; data not shown). These properties are similar to those of the 92-residue Mo-92 ectodomain from Mo-MLV, which also folds as a stable helical structure ([θ]222 = −21,000 deg·cm2⋅dmol−1, or ≈54 helical residues; ref. 12).

The coiled coil in the Mo-MLV TM protein core contains a buried Asn residue that coordinates a chloride ion, as judged by both biochemical and x-ray crystallographic evidence (10). A similar Asn residue also is conserved in the Ebola GP2 core (Asn-586). To investigate the ion-binding properties of Ebo-74, thermal unfolding experiments were performed in the presence of different monovalent anions. Chloride and bromide ions result in substantial stabilization of Ebo-74, whereas fluoride has very little effect (apparent Tm = 84°C, 84°C, 79°C, or 77°C in the presence of 5 mM NaCl, 5 mM NaBr, 5 mM NaF, or no added salt, respectively; data not shown). These results, very similar to those obtained earlier with Mo-55 (10), suggest that the anion binding site is conserved in Ebo-74.

Ebo-74 Structure Determination.

Although Ebo-74 contains significantly more residues than Mo-55, and there is only 22% sequence identity between Ebo-74 and Mo-55, the overall similarities of these cores prompted us to attempt to solve the Ebo-74 crystal structure with a molecular replacement approach. A solution was found by using a trimeric polyserine model of Mo-55 (10), with the loop regions omitted and a chloride ion retained in the core (i.e., the model contained only 36% of the atoms in the target structure). This solution became apparent after the fitting procedure in amore (final correlation coefficient = 0.431 and R factor = 0.484 in the resolution shell 10.0 to 4.0 Å), and it also resolved the ambiguity in space group determination in favor of P62. Initial phases, calculated from the correctly positioned model, were dramatically improved by using 3-fold averaging with dm (25). The initial dm-phased electron density map clearly revealed the structures of the omitted loops and the C-terminal helices absent from the trial model. The quality of the map was further improved through noncrystallographic symmetry matrix refinement (25) and solvent mask redefinition with the program ncsmask (23). An initial model of Ebo-74 was built based on this map and then refined to convergence. The final 2Fo − Fc electron density map is of good quality (see Fig. 4) and reveals the positions of all of the amino acid residues except for a few disordered side chains at the chain termini and on the protein surface.

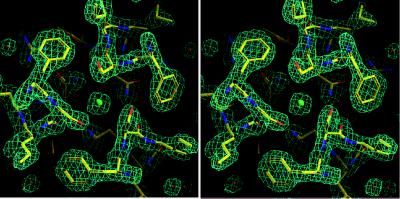

Figure 4.

Chloride-binding site within the central coiled coil of Ebo-74 as visualized in a stereo view of the final 2Fo − Fc electron density map. A chloride ion and water molecules are shown as green and red spheres, respectively. The map was contoured at 1.5 σ. Figure was generated by using o (26).

Overall Architecture of Ebo-74.

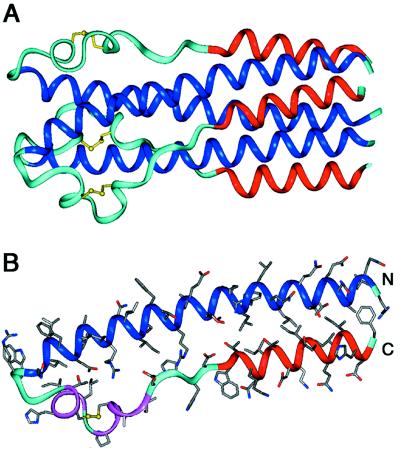

As expected, Ebo-74 forms a homotrimer. Each of the three polypeptide chains folds into a helical-hairpin conformation, in which two antiparallel helices are connected by a loop region (Fig. 3). The N-terminal helices from each monomer form a central, three-stranded coiled coil. This coiled-coil core includes approximately 35 residues (561–595) from each chain (the two most N-terminal residues are not well defined in the electron density maps and next two are in a random-coil conformation). Shorter C-terminal helices (residues 615–629) pack in an antiparallel manner into hydrophobic grooves on the surface of the coiled-coil core (the C-terminal Phe-630 residue is disordered in all chains). In the loop region connecting the N- and C-terminal helices, a disulfide between Cys-601 and Cys-608 links a short α-helix (residues 600–604) and a short 310-helix (residues 606–610). Additionally, the loop region between the 310-helix and C helix (residues 611–614) are in an extended conformation. Because of asymmetric crystal contacts, the three individual chains in the Ebo-74 structure have slight differences in conformation and degree of order, with the B chain having a higher overall B factor (43.1 Å2) than the A and C chains (37.7 and 37.1 Å2, respectively). The rms deviation between the individual chains in the Ebo-74 noncrystallographic trimer vary from 0.74 Å (chains A and C) to 1.31 Å (chains B and C).

Figure 3.

Ebo-74 forms a trimer-of-hairpins structure. (A) A side view of the Ebo-74 structure. N helices (dark blue) constitute a central coiled coil and C helices (red) pack into hydrophobic grooves on the surface of the coiled coil. Disulfides within the loop regions (light blue) are depicted in yellow. (B) Each monomer has an α-helical hairpin conformation. The last three turns of the N helix, followed by the short α- and 310-helices (magenta), correspond to the immunosuppressive motif region in oncogenic retroviruses. Figure was generated by using insight ii (64).

Chloride-Binding Site of Ebo-74.

Asn and Gln residues in the cores of some three- or five-stranded coiled coils bind chloride ions (10, 28–30), although other three-stranded coiled coils with buried Asn or Gln residues, including those in the core structures of HIV-1 and SIV gp41, apparently do not bind ions (14, 16, 31–34). In the Ebo-74 structure, a strong x-ray scatterer binds between the adjacent rings of Ser-583 and Asn-586 residues (Fig. 4). This density was identified as a chloride ion based on several lines of evidence. First, solution studies described above indicate that chloride and bromide ions can bind Ebo-74. Second, chloride is present in the crystallization solution. Third, the individual B factor refinement of a modeled chloride ion converges at 24.1 Å2; the same value is obtained for the average B factor of the interacting amide nitrogens of the Asn-586 residues. Finally, the average distance between the ion and the interacting nitrogen atoms is 3.28 Å, similar to the distances observed for chloride binding in other coiled coils (10, 28–30) and close to the sum of the van der Waals radii for NH4+ and Cl− (3.24 Å; ref. 35). If a chloride-binding site is common in other fusion glycoproteins with analogous architectures and can be substituted by bromide, the bromide complex would be an attractive target for multiple-wavelength anomalous dispersion phasing experiments when molecular replacement methods fail to permit x-ray structure determination.

Irregularities in the Ebo-74 Coiled Coil.

Visual analysis and superposition of the Ebo-74 coiled-coil structure with the structures of regular three-stranded coiled coils (e.g., GCN4-pIQI, ref. 29; or Mo-55, ref. 10) reveal clear irregularities at the N-terminal end of the Ebo-74 coiled coil (Fig. 5). In terms of superhelix parameters (36–38), this deviation can be described as an unwinding of the superhelix (decrease in ωo) and an increase in the a-position orientation angle (φ), with a decrease in the superhelix crossing angle (χ). Indeed, in the first three helical turns of the Ebo-74 coiled coil, the helices are almost straight. As a result, the helices are further apart than in the regular coiled-coil region of Ebo-74 (supercoil radius Ro = 7.0 Å vs. 6.3 Å), and knobs-into-holes packing interactions, a hallmark of coiled coils, are lost.

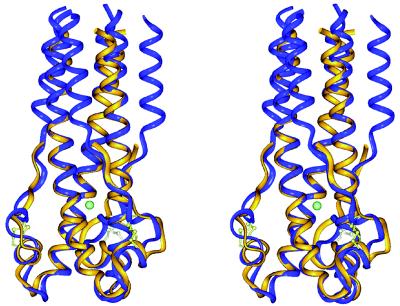

Figure 5.

Remarkable similarity between filovirus and retrovirus membrane-fusion proteins. A stereo view of the superposition of the Ebo-74 (blue) and the Mo-55 (yellow) structures is shown. The location of the chloride ion is almost identical in the superposition. The largest deviations occur at the N termini and in the loop regions of the Ebo-74 and Mo-55 structures. The rms deviation values for the Cα atoms of Ebo-74 and Mo-55 monomers (and values for trimers in parentheses) are as follows: entire structure 1.56 Å (1.84 Å); coiled-coil cores 0.49 Å (0.94 Å); loop regions 1.91 Å (2.33 Å). Figure was generated by using insight ii (64).

An irregularity at the N-terminal end of the Ebola GP2 coiled coil also exists in the crystal structure of the GP2 fragment fused to an N-terminal GCN4 trimeric coiled coil (17). Our results indicate that this irregularity is not imposed by the GCN4 coiled coil. The N-terminal ends, however, are where the most significant differences exist between the structures of the Ebola-GCN4 fusion protein (17) and Ebo-74. Specifically, the Ebola-GCN4 fusion protein (17) has nine additional helical residues in an α-helical conformation at the N terminus, as compared with Ebo-74 structure. (Four of those nine are present in Ebo-74 as disordered or nonhelical residues, and the remaining five are not present.) It is possible that the GCN4 coiled coil has forced these residues into an α-helical conformation in the Ebola-GCN4 fusion, or alternatively, it could be that end-effects in the Ebo-74 construct cause these residues to unfold. In addition, the irregularity at the N-terminal end of the coiled coil has been described as a “stutter” in the Ebola-GCN4 fusion protein (17, 39), but the lack of knobs-into-holes packing at the N-terminal end of Ebo-74 makes the definition of the heptad-repeat position irrelevant in this case.

Interestingly, the otherwise quite similar Mo-55 structure has a very regular structure throughout its coiled coil (10). The irregularity in the Ebo-74 coiled coil might be determined by the sequence of the coiled-coil region or may result from interactions of the C-terminal helices with the N-terminal coiled coil, because the C-terminal helices are not present in the Mo-55 fragment. However, as is demonstrated by the HIV-1 and SIV gp41 core structures, C-terminal helices can pack against a central N-terminal coiled coil without distorting the coiled-coil structure (14, 16, 31, 32).

DISCUSSION

Although there is only 22% sequence identity between residues in Ebo-74 from Ebola virus and Mo-55 from Mo-MLV, the location of these identical residues suggested very similar structures (ref. 10; see also ref. 11). The similarity between the Ebo-74 and Mo-55 structures is striking (Fig. 5), because no obvious evolutionary relationship exists between the filoviruses and the retroviruses. In addition, the corresponding receptor-binding domains [GP1 from Ebola or surface subunit (SU) from Mo-MLV] show no sequence similarity.

Ebo-74 contains C-terminal residues not present in Mo-55; they form C-terminal helices that pack against the central N-terminal coiled coil. Thus, the overall architecture of Ebo-74 is a trimer of helical hairpins. The core of the Mo-MLV TM protein likely also forms a trimer of helical hairpins, because CD studies indicate that Mo-92, a longer fragment of the Mo-MLV protein that includes Mo-55 as well as an additional 37 C-terminal residues, contains additional helical residues (12).

A trimer-of-hairpins structure is emerging as a general feature of many viral membrane-fusion proteins (Fig. 6). Besides the filovirus Ebola and the oncoretroviruses Mo-MLV and HTLV-1 (10, 17, 40), trimer-of-hairpins structures are found in membrane-fusion proteins from the orthomyxovirus influenza (41), the lentiviruses HIV-1 and SIV (14, 16, 31–33), and the paramxyovirus SV5 (42, 43). In addition, a recently developed computer program, learncoil-vmf, detects coiled coil-like regions with the potential to form trimer-of-hairpins structures in a large number of viral membrane-fusion proteins (ref. 44; M. Singh, B. Berger, and P.S.K., unpublished work). There is substantial variation in the size of the loop in these hairpin structures. Nonetheless, in each case the N-terminal region of the protein, which contains the fusion peptide, is brought close to the C-terminal region of the ectodomain, which connects to the transmembrane helix of the protein. Thus, given that the fusion peptide inserts into the cell membrane and the transmembrane helix is anchored in the viral membrane, the likely role of the hairpin structure is to facilitate the apposition of the viral and cellular membranes (31, 45–47). How membrane apposition leads to complete membrane fusion is unclear, but the mechanism likely involves membrane distortion and/or clustering of trimers to form fusion pores (see e.g., refs. 48–50). Interestingly, it recently became apparent that cellular membrane-fusion processes mediated by the SNARE proteins also use coiled-coil structures as a means to generate apposition of membranes for fusion (51–54).

Figure 6.

Trimer-of-hairpins structures in viral membrane-fusion proteins. Side and top views of the fusion proteins from three different groups of viruses are shown. (Top) Ebola (this work and ref. 17) and Mo-MLV (10). (Middle) SIV (16, 33) and HIV-1 (14, 31, 32). (Bottom) Influenza (41). The N-terminal coiled-coil cores are depicted in dark blue. In all structures, the trimer-of-hairpins conformation brings the N and C termini, and therefore the fusion peptides and transmembrane helices, into close proximity. Figure was generated by using insight ii (64).

In viral membrane-fusion proteins, the trimer-of-hairpins structure presumably corresponds to the fusion-active state, distinct from the native (nonfusogenic) state. In the best-studied cases, a conformational change activates the native membrane-fusion protein. In the dramatic “spring-loaded” mechanism, a long loop in the native HA1/HA2 complex of influenza forms a three-stranded coiled coil in the fusogenic state on exposure to low pH (41, 55). For HIV, a substantial conformational change in the gp120/gp41 complex that activates gp41 is triggered by binding to cell-surface receptors, although the details of this change are only starting to be understood (see ref. 47 and references therein). For Ebola, relatively little is known about the native GP1/GP2 complex, but the transition to the fusogenic state likely also involves a substantial conformational change (see discussion in ref. 56).

Finally, the Ebo-74 structure may assist in the discovery of agents that prevent infection by Ebola virus. Synthetic peptides corresponding to the C-terminal helices of the trimer-of-hairpin structures in HIV-1 (13, 16, 57–59) or in paramyxoviruses (42, 60–62) are inhibitors of entry by those viruses. The C-peptide inhibitors of HIV-1 have been particularly well characterized, and likely act in a dominant-negative manner by binding to a transient “pre-hairpin” intermediate of gp41 (refs. 47, 59, and 63, and references therein). In an analogous manner, peptides corresponding to regions of Ebo-74 that pack against the central three-stranded coiled coil may inhibit Ebola infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David C. Chan for numerous helpful discussions, Jodi M. Harris for assistance in preparation of the manuscript and figures, Dr. Deborah Fass and the Kim lab for comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Thomas Earnest for beamtime allocation and help at the 5.0.2 beamline at the Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA). This research used the W. M. Keck Foundation X-ray Crystallography Facility at the Whitehead Institute and was funded by the National Institutes of Health (PO1 GM56552).

ABBREVIATIONS

- TM

transmembrane subunit

- GP

glycoprotein

- Mo-MLV

Moloney murine leukemia virus

- HIV-1

HIV type 1

- SIV

simian immunodeficiency virus

- Ebo-74

Ebola GP2 fragment, residues 557-630

- Ebo-95

Ebola GP2 fragment, residues 549-643

- Mo-55

Mo-MLV fragment, residues 44-98

Footnotes

Data deposition: The coordinates reported in this paper have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Biology Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973 (PDB ID code 2ebo) and are available immediately at http://www.wi.mit.edu/kim/home.html.

References

- 1.Jahring, P. B., Kiley, M. P., Klenk, H.-D., Peters, C. J., Sanchez, A. & Swanepoel, R. (1995) Arch. Virol.10, Suppl., 289–292.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbid Mortal Week Rep. 1995;44:381–382. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldmann H, Klenk H-D. Adv Virus Res. 1996;47:1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez A, Ksiazek T G, Rollin P E, Peters C J, Nicol S T, Khan A S, Mahy B W J. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1:96–97. doi: 10.3201/eid0103.950307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Z, Delgado R, Xu L, Todd R F, Nabel E G, Sanchez A, Nabel G J. Science. 1998;279:1034–1037. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez A, Trappier S G, Mahy B W J, Peters C J, Nichol S T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3602–3607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volchkov V E, Feldmann H, Volchkova V A, Klenk H-D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5762–5767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Strauss S E, editors. Fields Virology. 3rd Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volchkov V E, Blinov V M, Netesov S V. FEBS Lett. 1992;305:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80662-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fass D, Harrison S C, Kim P S. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:465–469. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallaher W R. Cell. 1996;85:477–478. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fass D, Kim P S. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu M, Blacklow S C, Kim P S. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/nsb1295-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan D C, Fass D, Berger J M, Kim P S. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blacklow S C, Lu M, Kim P S. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14955–14962. doi: 10.1021/bi00046a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malashkevich V N, Chan D C, Chutkowski C T, Kim P S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9134–9139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissenhorn W, Carfi A, Lee K-H, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Mol Cell. 1998;2:605–616. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen G Q, Choi I, Ramachandran B, Gouaux J E. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:8799–8800. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schumacher T N M, Mayr L M, Minor D L, Jr, Milhollen M A, Burgess M W, Kim P S. Science. 1996;271:1854–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelhoch H. Biochemistry. 1967;6:1948–1954. doi: 10.1021/bi00859a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthews B W. J Mol Biol. 1968;33:491–497. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otwinowski Z. In: Data Collection and Processing. Sawer L, Isaacs N, Bailey S, editors. Daresbury Laboratory, Warrington, U.K.: SERC; 1993. pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.CCP4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navaza J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowtan K D. Joint CCP 4 ESF-EACBM Newslett Protein Crystallogr. 1994;31:43–38. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones T A, Zou J Y, Cowan S W, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr D. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brünger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, DeLano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malashkevich V N, Kammerer R A, Efimov V P, Schulthess T, Engel J. Science. 1996;274:761–765. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckert D M, Malashkevich V N, Kim P S. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:859–865. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nautiyal S, Alber T. Protein Sci. 1999;8:84–90. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.1.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Nature (London) 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12303–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caffrey M, Cai M, Kaufman J, Stahl S J, Wingfield P T, Covell D G, Gronenborn A M, Clore G M. EMBO J. 1998;17:4572–4584. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez L, Jr, Woolfson D N, Alber T. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:1011–1018. doi: 10.1038/nsb1296-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weast R C. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crick F H C. Acta Crystallogr. 1953;6:685–689. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harbury P B, Kim P S, Alber T. Nature (London) 1994;371:80–83. doi: 10.1038/371080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harbury P B, Tidor B, Kim P S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8408–8412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown J H, Cohen C, Parry D A. Proteins. 1996;26:134–145. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199610)26:2<134::AID-PROT3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobe, B., Center, R. J., Kemp, B. E & Poumbouris, P. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Bullough P A, Hughson F M, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Nature (London) 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joshi S B, Dutch R E, Lamb R A. Virology. 1998;248:20–34. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker, K. A., Dutch, R. E., Lamb, R. A. & Jardetzky, T. S. (1999) Mol. Cell, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Berger B, Singh M. J Comput Biol. 1997;4:261–273. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1997.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughson F M. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R565–R569. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furuta R A, Wild C T, Weng Y, Weiss C D. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:276–279. doi: 10.1038/nsb0498-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan D C, Kim P S. Cell. 1998;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chernomordic L V, Frolov V A, Leikina E, Bronk P, Zimmerberg J. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1369–1382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanaseki T, Kawasaki K, Murata M, Ikeuchi Y, Ohnishi S. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1041–1056. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danieli T, Pelletier S L, Henis Y I, White J M. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:559–569. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.3.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sutton R B, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brünger A T. Nature (London) 1998;395:347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weber T, Zemelman B V, McNew J A, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Sollner T H, Rothman J E. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin R C, Scheller R H. Neuron. 1997;19:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanson P I, Roth R, Morisaki H, Jahn R, Heuser J E. Cell. 1997;90:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carr C M, Kim P S. Cell. 1993;73:823–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90260-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carr C M, Chaudhry C, Kim P S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14306–14313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang S, Lin K, Strick N, Neurath A R. Nature (London) 1993;365:113. doi: 10.1038/365113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wild C T, Shugars D C, Greenwell T K, McDanal C B, Matthews T J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9770–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan D C, Chutkowski C T, Kim P S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15613–15617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rapaport D, Ovadia M, Shai Y. EMBO J. 1995;14:5524–5531. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lambert D M, Barney S, Lambert A L, Guthrie K, Medinas R, Davis D E, Bucy T, Erickson J, Merutka G, Petteway S R., Jr Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2186–2191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao Q, Compans R W. Virology. 1996;223:103–112. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kilby J M, Hopkins S, Venetta T M, DiMassimo B, Cloud G A, Lee J Y, Alldredge L, Hunter E, Lambert D, Bolognesi D, et al. Nat Med. 1998;4:1302–1307. doi: 10.1038/3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Molecular Simulations. insight ii, Molecular Modeling System User Guide. San Diego, CA: Molecular Simulations; 1997. [Google Scholar]