Abstract

We are investigating a novel pretargeting approach involving an initial IV injection of antitumor antibody conjugated with a phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer (MORF, a DNA analog) and the subsequent IV injection of the radiolabeled complement oligomer (cMORF). In this paper, the cMORF was labeled with 188Re using MAG3 as chelator for therapeutic applications. Since (c)MORFs are unstable in acidic condition, an optimal labeling pH was first selected and the other labeling factors were then examined. A labeling efficiency of greater than 90% can be achieved even at a concentration of MAG3–cMORF as low as 0.8 μM. The labeled cMORF is stable and capable of hybridizing to its complement.

Keywords: Rhenium-188, Radiolabeling, DNA analog, Pretargeting

1. Introduction

The objective of this investigation was to develop a method of labeling phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (MORFs) with 188Re for tumor pretargeting investigations. Rhenium-188 is often the radiotherapeutic nuclide of choice especially for biomolecules already capable of being labeled with technetium-99 m (99mTc). We reported earlier on method (Liu et al., 2003) for the labeling of MORFs with 188Re using MAG3 as chelator, which was modified only slightly from methods used to radiolabel with 99mTc (Mang’era et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2002a). However, in vivo instability leading to 188Re-perrhenate was at level that would be unacceptable for radiotherapy. As an alternative, labeling via 188Re-tricarbonyl [188Re(CO)3 +] was considered (He et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2004a), to take advantage of the reported chemical inertness against re-oxidation. However, while in vivo stability was improved, it was not possible to achieve the high specific radioactivity levels required for radiotherapeutic applications (Liu et al., 2004a). This paper describes the results obtained in a revisit of the MAG3 approach for 188Re labeling of the cMORF useful in pretargeting studies.

The N3S chelators with a coordinating site consisting of one thiol sulfur and three amide nitrogens have been widely employed for 188Re and 186Re labeling. For antibodies and other carriers that are sensitive to heating, a common strategy is to adopt pre-conjugation labeling. In this strategy, the 188Re- or 186Re-MAG3 active ester is first prepared and then conjugated to biomolecule carriers. Radiolabeled in this fashion, a 186Re-MAG3-antibody was shown to be stable in plasma for up to 30 h (Kievit et al., 1997). Different N3S chelators have been used in this way, such as MAG2-GABA (S-ethoxyethyl mercaptoacetyl-glycylglycyl aminobutyrate) (Vanderheyden et al., 1989; Goldrosen et al., 1990), S-benzoyl-MAG3 (Visser et al., 1993; Gerretsen et al., 1993), and MAGIPG (N-(S-acetylmercaptoacetyl)(p-NCS)phenylalanylglycine ethyl ester) (Ram et al., 1997). The disadvantages of pre-conjugation labeling include the extensive manipulations with highly radiotoxic therapeutic nuclides and the need for post-labeling purification. In the case of carriers that can withstand harsh environments, post-conjugation labeling should be possible and more practical. However, although a few post-conjugation 188Re labeling have been reported (Guhlke et al., 1998; Pearson et al., 1996; Zinn et al., 2000; Polyakov et al., 2000; Gestin et al., 2001), to our knowledge, none describes 188Re labeling of a biomolecule at high labeling efficiency and high specific radioactivity.

This laboratory has been using S-acetyl protected and N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated MAG3 ester for 99mTc labeling. It is in routine use for post-conjugation labeling with 99mTc of proteins, peptide and oligomers at slightly basic pH and at room temperature (Winnard et al., 1997; Hnatowich et al., 1997, 1998; Rusckowski et al., 2000). However, the labeling efficiency is usually not quantitative and therefore post-labeling purification is often necessary. In recent investigations of the 99mTc labeling of MAG3-cMORF, heating was found to increase the labeling efficiency to about 80% but with the appearance of radiolabeled impurities (Mang’era et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2002a). Further investigations showed that the impurities were not due to incomplete purification of the MAG3- cMORF after conjugation but were generated during 99mTc labeling (Liu et al., 2002b) and led to the conclusion that these impurities could be removed by introducing the preliminary purification procedure described below. As a result, labeling efficiency of MAG3-cMORF with 99mTc now routinely exceeds 95% (unpublished observations). A MAG3-cMORF preparation has now been stored for more than 1 year at −20 ° C and still provides labeling efficiencies with 99mTc exceeding 95%.

In the previous method from this laboratory on 188Re labeling of MAG3-cMORF (Liu et al., 2003), the MAG3-cMORF was prepared without this preliminary purification procedure and the labeling method was not optimized. In this present study, the preliminary purification procedure has been included.

2. Material and methods

The MORF (MW 6164) and its complement (cMORF, MW 6331) of this investigation were each purchased with a primary amine on the 3′ equivalent end linked via a 6-member linker. As defined for the purposes of this report, the base sequences of MORF and cMORF were respectively 5′ -TCTTCTACTTCACAACTA and 5′ -TAGTTGT-GAAGTAGAAGA (Gene Tools, Philomath, OR). The S-acetyl NHS-MAG3 was synthesized in house (Winnard et al., 1997) and the structure was confirmed by elemental analysis, proton NMR and mass spectroscopy. The anti CEA antibody MN14 (MW 160,000) was a gift from Immunomedics (Morris Plains, NJ). The 188Re perrhenate eluate was obtained from an 188W/188Re generator (Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN) and the 99mTc pertechnetate was from a 99Mo/99mTc generator (Perkin Elmer Life Science Inc, Boston, MA). The Bio-Gel P4 Gel (medium, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and all other chemicals were reagent grade and were used as received.

2.1. HPLC analysis

Both the reverse phase (RP) and size exclusion (SE) high-performance liquid chromatographs (HPLC) were equipped with an in-line radioactivity detector and an inline Waters 2487 dual wavelength absorbance detector (Milford, MA). Recovery of radioactivity was routinely measured with co-injection of about 10 μg unlabeled cMORF and was always over 85%. Both perrhenate and pertechnetate are retained on SE column but not RP C-18 column.

The RP HPLC was used to evaluate the labeling of cMORF and the stability of 188Re-cMORF in phosphate buffer and was performed on a C-18 column (5 μ, 250 × 4.6 mm, Vydac, The Nest Group, Inc, Southboro, MA) with 0.05 M TEAP (triethylamine phosphate, pH 4.6) as solvent A and methanol/acetonitrile (v/v = 80/20) as solvent B at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Gradient table: 0–3 min, 100% A; 3–6 min, 100–75% A; 6–9 min, 75–66% A; 9–20 min, 66–0% A; 20–37 min, 0% A; 37–40 min, 0–100% A; 40–50 min, 100% A.

The SE HPLC was used along with paper chromatography to investigate the integrity of 188Re-cMORF and its stability in serum and was performed on a Superose-12 HR10/30 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscat-away, NJ) with an optimal separation range between 1 × 103–3 × 105 Da. The 0.10 M pH 7.2 phosphate buffer was used as eluant at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. In addition, paper chromatography was performed on Whatman No. 1 paper with acetone as the mobile phase to detect 188Re perrhenate. In this system, perrhenate migrates to the solvent front (Rf = 0.9 − 1.0) while labeled cMORF and other labeled impurities stay at the application point (Rf = 0.0−0.1).

2.2. Preparations of 99mTc MAG3-cMORF and MORF-MN14

The MAG3-cMORF conjugate was prepared as follows: 1.5 mg of cMORF was dissolved in 0.2 M, pH 8.0 HEPES to a concentration of 0.5 mg/100 μL and the solution was added to a vial containing S-acetyl NHS-MAG3 at a MAG3/amine molar ratio of 10–25. After 2 h incubation at room temperature, the reaction mixture was purified over a P4 column (0.7 × 20 cm) using 0.25 M, pH 5.2 NH4OAc buffer as eluant. The peak fractions at 265 nm with an OD greater than 1.5 were pooled. A preliminary purification procedure was performed by mixing the pooled cMORF solution with a pH 9.2 tartrate buffer (50 μg/μL Na2tartrate × 2H2O, 0.5 M Na2HCO3, 0.25 M NH4OAc, 0.175 M NH3) and a fresh tin solution (10 μg/μL SnCl2 · 2H2O, 1 μg/μL Na ascorbate, 10 mM HCl) at a volume ratio of cMORF solution/tartrate buffer/tin solution of 15/5/1, followed by heating for 20 min and then a final purification over a P4 column (1.0 × 50 cm). The peak fractions with OD values greater than 1.5 were pooled again and were stored at −20 ° C. This preparation has now been used for 99mTc labeling for over 1 year with minimal loss in labeling efficiency and is now in use for 188Re labeling.

Radiolabeling with 99mTc of the MAG3-cMORF was as follows: 50 μL of 99mTc-pertechnetate eluant was introduced into a combined solution consisting of 30 μL (preferably no less than 0.5 μg) of MAG3-cMORF in pH 5.2 NH4OAc buffer, 10 μL of 50 μg/μL Na2tartrate ·2 H2O in the pH 9.2 buffer and 3 μL of 4 μg/μL SnCl2 ·2 H2O in ascorbate-HCl solution (1 μg/μL Na ascorbate in 10 mM HCl), followed by heating at 100 ° C for 20 min. The final pH was 7.8 and the labeling efficiency was routinely greater than 95%.

The antiCEA IgG antibody MN14 was conjugated with MORF and used to confirm the hybridization property of cMORF after labeling with 188Re. The conjugation was achieved using a commercial Hydralink method (Solulink, San Diego, California).

2.3. Initial labeling of MAG3-cMORF with 188Re

Initially, 50 μL of 188Re perrhenate was added to a combined solution of 30 μL of MAG3-cMORF (0.4 μg/μL) in pH 5.2, 0.25 M NH4OAc buffer, 10 μL Na2 tartrate ·2H2O (50 μg/μL) in 0.5 N HCl, and 20 μL of SnCl2 · 2H2O (10 μg/μL) in 20 mM HCl containing 1 μg/μL of Na ascorbate, followed by heating in a boiling water bath for 1 h. The pH was 3.3 as suggested (Guhlke et al., 1998).

The influence of additional heating for 0, 1, 2 and 3 h on the formation of radiolabeled impurities during the preparation of 188Re-cMORF was examined by RP HPLC. To help establish whether the observed radiolabeled impurities were due to instability of the 188Re label or the cMORF itself, the study was repeated with 99mTc as label. The 99mTc-cMORF was labeled at pH 7.8 and was adjusted to pH 3.4 before heating for an additional 0, 1, 2, or 3 h.

2.4. Optimization of the labeling procedure

The optimization procedure was as follows: 30 μL of MAG3-cMORF at various concentrations in the pH 5.2, 0.25 M NH4OAc buffer was added to a combined solution of 10 μL of Na2 tartrate ·2H2O (50 μg/μL) in either HCl (0.0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 or 0.4 M), NaOH (0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 M), or the above pH 9.2 buffer and 20 μL of SnCl2 ·2H2O at various concentrations in 20 mM HCl containing 1 μg/μL of Na ascorbate. Subsequently, 50 μL of 188Re perrhenate generator eluant was added and the solution with a total volume of 110 μL was heated in a boiling water bath.

The conditions of the optimization studies are summarized in Table 1. In brief, the influence of labeling pH on labeling efficiency in the range from 3.3 to 8.2 was first examined by changing the composition of the tartrate solution. Once the optimum pH was established, the influence of heating time at that pH value (4.6) was evaluated followed by the influence of the concentration of MAG3-cMORF and finally the influence of stannous ion concentration.

Table 1.

Parameter values during optimization of labeling conditions

| Optimization of: | Labeling pH | Heating time (h) | MAG3-cMORF (μg) | SnCl2 · 2H2O (μg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 3.3–8.2 | 1 | 12 | 200 |

| Heating time | 4.6 | 1–1.2 | 12 | 200 |

| Concentration of MAG3-cMORF | 4.6 | 1 | 0.2–12 | 200 |

| Concentration of Tin (II) | 4.6 | 1 | 1.6 | 0–400 |

2.5. In vitro stability and integrity of 188Re-MAG3-cMORF

Since excess stannous ion will prevent perrhenate formation and therefore provide an unrealistic assessment of stability against oxidation, the 188Re-labeled cMORF solution was purified from excess stannous ion on a P4 column with 0.1 M, pH 7.0 phosphate buffer as eluant and analyzed by RP HPLC over 24 h. The stability in serum was also examined by incubating 100 μL of the purified labeled preparation with 400 μL fresh human serum at 37 ° C over 24 h followed by analysis for protein binding by SE HPLC and for perrhenate by paper chromatography.

The hybridization property of MAG3-cMORF after labeling was evaluated by a SE HPLC shift assay in which 15 μ Ci (about 0.1 μg) of 188Re-labeled cMORF was analyzed with or without the addition of MN14-MORF in excess (20 μg, 0.53 MORF groups per antibody). Hybridization is evident by a shift in the radioactivity profile to earlier retention time.

2.6. Biodistribution in normal mice

Four normal CD-1 mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) each received 10 μCi (4.0 μg) of 188Re-labeled cMORF via a tail vein. The mice were sacrificed 3 h later by exsanguination following cardiac puncture under halothane anesthesia. Blood and other organs were removed, weighed, and counted in a Cobra II automatic gamma counter (Packard Instrument Company, CT) along with a standard of the injectate.

3. Results

3.1. Radiolabeling of MAG3-cMORF

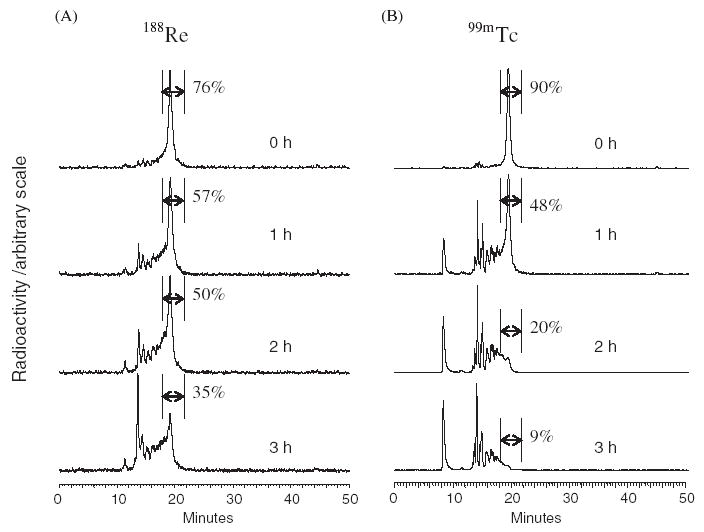

Radioimpurities were observed in the RP HPLC radio-chromatograms of 188Re-MAG3-cMORF labeled at pH 3.3 as shown in Fig. 1A (top panel). The labeling efficiency was less than 80% instead of over 90% as expected. The 188Re-MAG3-cMORF elutes in one main peak at 19 min with the impurities at 13–18 min. As shown (remaining panels of Fig. 1A), these impurities increase with increasing post-labeling heating time. Because cMORFs are unstable at pH 1 [Yongfu Li, GeneTools, private communication, 2005], these impurities were suspected to result from morpholino oligomer backbone fracture at acidic pH rather than from loss of the radiolabel. Since it is known that 99mTc-MAG3 is stable to heating at acid pH (unpublished observations), this instability of cMORF was further confirmed by heating 99mTc-MAG3-cMORF. When the pH was immediately adjusted to 3.3 from 7.8 (Fig. 1B, top panel), 99mTc-cMORF shows no impurity peaks. However, with increasing time of heating, radiochemical impurity peaks appear (remaining panels of Fig. 1B) in a similar manner to that observed for 188Re-cMORF. These results indicate that the formation of these radioactive impurities is not a consequence of 188Re label instability but rather a decomposition or hydrolysis of cMORF at low pH especially upon heating.

Fig. 1.

RP HPLC radiochromatograms showing the influence of heating time on the profile of cMORF radiolabeled at pH 3.3 with 188Re (column A) and with 99mTc (column B). Radiochemical purity is indicated.

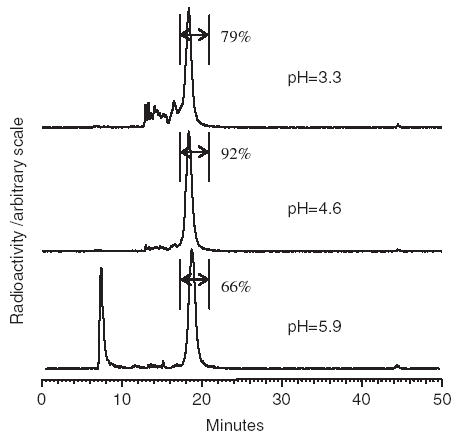

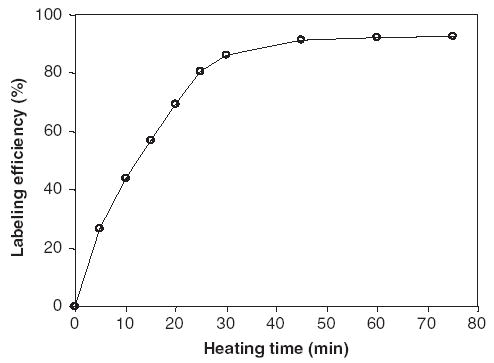

The radiochemical purity determined by RP HPLC reached a maximum of greater than 90% at pH 4.6. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 2, labeling at this pH also provides the cleanest RP HPLC radiochromatograph. At lower pH, hydrolysis of the cMORF backbone becomes more pronounced, while at higher pH perrhenate becomes evident by the peak at 8 min. As shown in Fig. 3, 1 h of heating is sufficient, in agreement with the literature (Guhlke et al., 1998).

Fig. 2.

RP HPLC radiochromatograms of 188Re-cMORF prepared at pH 3.3, 4.6, and 5.9. Radiochemical purity is indicated.

Fig. 3.

Influence of heating time on the efficiency of labeling 188Re-cMORF at pH 4.6.

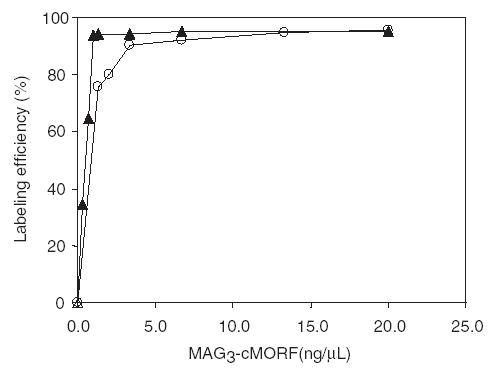

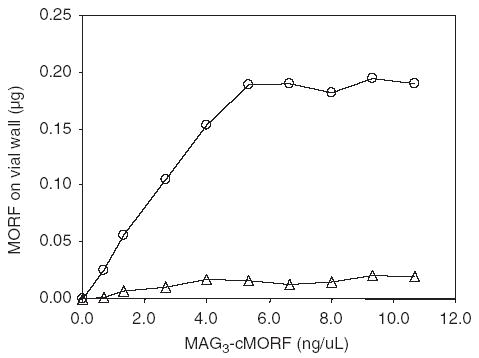

Fig. 4 shows the influence of MAG3-cMORF concentration on labeling efficiency. As show (open circles), labeling efficiency exceeds 90% at concentrations above 5.0 ng/μL of MAG3-cMORF (about 0.5 μg, 0.8 μM). However this concentration limit is misleading since at low concentration a significant fraction of MAG3-cMORF is lost from solution by adsorption to the vial wall. Fig. 5 presents the weight of MAG3-cMORF adsorbed to the vial wall of 0.5 mL micro-centrifuge tube (VWR, Bridgeport, NJ) when added in 60 μL at different MAG3-cMORF concentrations. As shown (open circles), the adsorption is saturated at about 5 ng/μL. However, after two washes with 1% human serum albumin, the MAG3-cMORF left on the wall drops to insignificance (open triangles). Unfortunately, the addition of HSA during labeling is impractical because HSA cannot withstand boiling water temperature, but its addition after labeling is useful to minimize adsorption during dose preparation and analysis. If the adsorption of MAG3-cMORF is avoided by adding native cMORF, as shown in Fig. 4, a labeling efficiency of greater than 90% may be achieved at even lower concentrations of MAG3-cMORF (closed triangles), as a reflection of the robust chelating ability of MAG3.

Fig. 4.

Labeling efficiency of 188Re-MAG3-cMORF with increasing weight of MAG3-cMORF with (○) and without (▴) the loss from solution of MAG3-cMORF to the vessel wall.

Fig. 5.

Adsorption behavior of 60 μL-radiolabeled cMORF on the vessel wall.

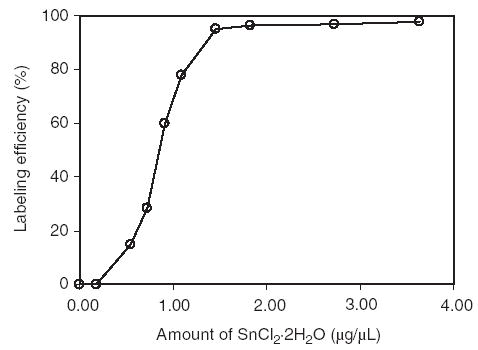

Fig. 6 shows that at least 1.5 μg/μL (160μg) of SnCl2 ·2H2O is necessary to achieve a labeling efficiency of greater than 90%, but concentrations of SnCl2 ·2H2O in excess of 2.8μg/μL (300μg) resulted in precipitation of stannous hydroxide.

Fig. 6.

Influence of stannous ion on the labeling efficiency of 188Re-cMORF after 1 h of heating at pH 4.6.

Upon optimization of all labeling conditions, a 188Re labeling efficiency of greater than 90% can be achieved with the following procedure: 50 μL of 188Re perrhenate was added to a combined solution of 30 μL of pH 5.2, 0.25 M NH4OAc buffer containing more than 0.2 μg but preferably 0.5 μg MAG3-cMORF, 10 μL Na2 tartrate ·2H2O (50 μg/μL) in H2O and 20 μL of SnCl2 ·2H2O (10 μg/μL) in 20 mM HCl containing 1 μg/μL of Na ascorbate, followed by heating in a boiling water bath for 1 h.

3.2. In vitro stability and integrity of 188Re-MAG3-cMORF

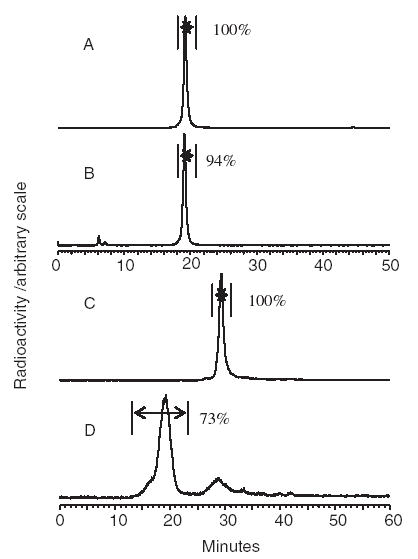

The RP HPLC radiochromatograms of Fig. 7 show a single peak (panel A) that remains essentially unchanged at least over 24 h at room temperature (panel B), serving as evidence of in vitro stability against oxidation. The 188Re-cMORF was prepared according to the above-optimized procedure and the stannous ion was removed as earlier mentioned. As shown by SE HPLC (panel C), the label is also stable in 37 ° C human serum for at least 24 h. The recovery in these analyses was over 90%. No evidence for perrhenate in these samples was found by paper chromatography (data not presented). Finally, almost the entire 188Re-labeled cMORF peak was shifted to the position of the antibody by the addition of MN14-MORF (panel D), indicating that the hybridization property of cMORF was unchanged after conjugation and labeling.

Fig. 7.

RP HPLC radiochromatograms of 188Re-cMORF purified from excess stannous ion analyzed immediately (panel A) and 24 h post-labeling (panel B) and the SE HPLC radiochromatograms of the same 188Re-cMORF preparation after incubation in 37 ° C human serum for 24 h before (panel C) and after (panel D) the addition of MN14-MORF. Radiochemical purity is indicated.

3.3. Biodistribution of 188Re-cMORF

The biodistribution data in normal mice obtained at 3 h post intravenous administration of 188Re-cMORF are listed in Table 2. Historical results in an identical study of 99mTc-cMORF (Liu et al., 2004b) are also included for comparison. Statistical analysis shows significant differences only for salivary gland and gastrointestinal tract with values for 188Re lower in both cases (Student’s t test P < 0.05). The low accumulations of 188Re labeled cMORF in salivary gland and stomach indicate the 188Re-cMORF is stable to oxidation in vivo since perrhenate strongly accumulates in these two organs (Zuckier et al., 2004). The stomach, large and small intestines were weighed and counted with contents, therefore values for these organs are reported only as %ID/organ.

Table 2.

Biodistribution of 188Re- and 99mTc-labeled cMORF in normal mice 3 h post IV administration

| %ID/g

|

%ID/organ

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ | 188Re-cMORF | 99mTc-cMORF | 188Re-cMORF | 99mTc-cMORF |

| Liver | 0.1470.04 | 0.1270.06 | 0.1970.06 | 0.2170.09 |

| Heart | 0.0370.01 | 0.0470.00 | 0.0070.00 | 0.0170.00 |

| Kidneys | 4.1170.75 | 3.2370.48 | 1.5970.43 | 2.0470.24 |

| Lungs | 0.0770.01 | 0.1170.02 | 0.0170.00 | 0.0370.00 |

| Spleen | 0.0670.03 | 0.0670.00 | 0.0170.00 | 0.0170.00 |

| Stomach | — | — | 0.2770.09 | 0.4270.08 |

| Sm. Int. | — | — | 0.1170.05 | 0.1370.03 |

| Lg. Int. | — | — | 0.1370.04 | 0.6170.05 |

| Muscle | 0.0270.01 | 0.0170.01 | 0.2170.06 | 0.2570.09 |

| Salivary gland | 0.3470.04 | 0.9070.30 | 0.0670.00 | 0.2770.10 |

| Blood | 0.0470.01 | 0.0670.01 | 0.0970.01 | 0.2070.02 |

Mean ± SD (n = 4).

The 99mTc values taken from (Liu et al., 2004b).

Biodistribution of 188Re-cMORF in normal mice after an additional P4 purification to remove the radioimpurities was also performed but showed no obvious differences (data not presented). This indicates that the impurities clear rapidly through the kidneys along with the labeled cMORF. Most probably the impurities are labeled and truncated cMORF and/or labeled tartrate. Therefore, to avoid unnecessary radiation exposure to personnel, the additional purification step was eliminated.

4. Discussion

Radiotherapy by MORF pretargeting will require that cMORF be radiolabeled with a therapeutic radionuclide. The choice of 188Re was dictated in part by the successful radiolabeling of cMORF with 99mTc and the chemical similarities between technetium and rhenium. However, while technetium and rhenium share similar chemical properties, there are important differences. For example, much more stannous ion and/or much lower pH values are needed to reduce perrhenate compared to pertechnetate. Furthermore, the radioactivity concentration of 188Re perrhenate in the eluant of the 188W/188Re generator is usually lower than that of 99mTc pertechnetate from the 99Mo/99mTc generator. Because of the higher oxidation potential of rhenium and the lower radioactivity concentration of 188Re, a higher concentration of both stannous ion and chelator concentration are often required for efficient 188Re labeling compared to 99mTc labeling.

Because of certain perceived advantages of technetium and rhenium tricarbonyl complexes, such as the expected chemical inertness, these complexes were previously considered by us as a method of labeling (c)MORFs (He et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2004a). Though high labeling efficiency with 99mTc was achieved, the specific activity was two orders of magnitude lower than that achievable using MAG3 as chelator. For example, a labeling efficiency in excess of 90% was achievable at chelator concentration no lower than about 10−4 M with the tricarbonyl approach while comparable labeling using MAG3 as chelator can be obtained at a chelator concentration as low as 0.8 × 10−6 M. In this regard, our experience with the tricarbonyl labeling is consistent with the literature (Egli et al., 1999; Schibli et al., 2000).

As mentioned above in connection with Fig. 4, adsorption has raised the concentration required to achieve a particular labeling efficiency. The decreased labeling efficiency with decreasing concentration is not due to the chelating ability of MAG3 on cMORF but to the loss of MAG3-cMORF from solution such that the cMORF concentration is lower than indicated therein. By adding unconjugated native cMORF to keep the total cMORF concentration constant, the concentration limit to achieve a labeling efficiency of over 90% is reduced to 2 ng/μL or 0.3 μM, as indicated in Fig. 4 (triangles). Late in this investigation, it was found that the use of non-stick surface micro-centrifuge tube (VWR, Bridgeport, NJ) could minimize the degree of adsorption during labeling.

In this present study, the MAG3 strategy for 188Re labeling of cMORF used unsuccessfully in the past (Liu et al., 2003) has been revisited. Reconsideration of this approach was driven by three factors: (1) the recent development of a labeling protocol for MAG3-cMORF which results in a 99mTc labeling efficiency of greater than 95% without postlabeling purification; (2) the failure to reach a high specific radioactivity with tricarbonyl approaches using histidine and dipicolylamine (Liu et al., 2004a); and (3) a literature survey suggesting that 188Re or 186Re-labeled MAG3 conjugate is stable against reoxidation.

For radiotherapeutic application of 188Re-labeled cMORF, besides the requirements that the radiolabel be stable both in vitro and in vivo and that the specific radioactivity be sufficiently high, the hybridization property of cMORF must be preserved. By using SE HPLC in a shift assay, we have demonstrated that the 188Re-radiolabeled cMORF of this investigation maintained hybridization affinity for its complement.

This investigation was performed with an aged 188W–188Re generator providing 188Re perrhenate at a concentration of only about 0.5 mCi/mL compared to about 10–100 mCi/mL for a new of 250–1000 mCi generator. Because of the no-carrier nature of 188Re, the labeling efficiency should not be influenced by the practical amount of radioactivity. Since radiolysis has not been found to be a problem with morpholino oligomer, a specific radioactivity of 2–25 mCi/μg cMORF should be achievable.

5. Conclusion

The MAG3 chelator for post-conjugation labeling of morpholino oligomers with 188Re has been shown to provide a stable label with specific radioactivity sufficiently high for radiotherapeutic applications without the need for postlabeling purification.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Gary Griffiths (Immunomedics, Morris Plains, NJ.) for providing the MN14 antibody for this investigation. Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health (CA94994 and CA107360).

References

- Egli A, Alberto R, Tannahill L, et al. Organometallic 99mTc-aquaion labels peptide to an unprecedented high specific activity. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1913–1917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerretsen M, Visser GW, van Walsum M, et al. 186Re-labeled monoclonal antibody E48 immunoglobulin G-mediated therapy of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3524–3529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestin JF, Loussouarn A, Bardies M, et al. Two-step targeting of xenografted colon carcinoma using a bispecific antibody and 188Re-labeled bivalent hapten: biodistribution and dosimetry studies. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:146–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldrosen MH, Biddle WC, Pancook J, et al. Biodistribution, pharmacokinetic, and imaging studies with 186Re-labeled NR-LU-10 whole antibody in LS174 T colonic tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7973–7978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhlke S, Schaffland A, Zamora PO, et al. 188Re- and 99mTc-MAG3 as prosthetic groups for labeling amines and peptides: approaches with pre- and postconjugate labeling. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;25:621–631. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(98)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Liu C, Vanderheyden JL, et al. Radiolabelling morpholinos with 188Re tricarbonyl provides improved in vitro and in vivo stability to re-oxidation. Nucl Med Commun. 2004;25:731–736. doi: 10.1097/01.mnm.0000130237.91573.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnatowich DJ, Chang F, Lei K, et al. The influence of temperature and alkaline pH on the labeling of free and conjugated MAG3 with technetium-99 m. Appl Radiat Isot. 1997;48:587–594. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(96)00331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnatowich DJ, Qu T, Chang F, et al. Labeling peptides with technetium-99 m using a bifunctional chelator of a N-hydroxysuccinimide ester of mercaptoacetyltriglycine. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kievit E, van Gog FB, Schluper HM, et al. Comparison of the biodistribution and the efficacy of monoclonal antibody 323/A3 labeled with either 131I or 186Re in human ovarian cancer xenografts. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:813–823. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Mang’era K, Liu N, et al. Tumor pretargeting in mice using 99mTc-labeled morpholino, a DNA analog. J Nucl Med. 2002a;43:384–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Zhang S, He J, et al. Improving the labeling of S-acetyl NHS-MAG3-conjugated morpholino oligomers. Bioconjug Chem. 2002b;13:893–897. doi: 10.1021/bc0255384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CB, Liu GZ, Liu N, et al. Radiolabeling morpholinos with 90Y, 111In, 188Re and 99mTc. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Dou S, He J, et al. Preparation and properties of 99mTc(CO)+3 -labeled N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-4-aminobutyric acid. Bioconjug Chem. 2004a;15:1441–1446. doi: 10.1021/bc049866a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, He J, Dou S, et al. Pretargeting in tumored mice with radiolabeled morpholino oligomer showing low kidney uptake. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2004b;31:417–424. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mang’era KO, Liu G, Yi W, et al. Initial investigations of 99mTc-labeled morpholinos for radiopharmaceutical applications. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1682–1689. doi: 10.1007/s002590100637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson DA, Lister-James J, McBride WJ, et al. Somatostatin receptor-binding peptides labeled with technetium-99m: chemistry and initial biological studies. J Med Chem. 1996;39:1361–1371. doi: 10.1021/jm950111m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyakov V, Sharma V, Dahlheimer JL, et al. Novel Tat-peptide chelates for direct transduction of technetium-99m and rhenium into human cells for imaging and radiotherapy. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:762–771. doi: 10.1021/bc000008y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram S, Merriwether W, Buchsbaum DJ. Synthesis and biodistribution of peptide based 99mTc/186Re-MAGIPG-D612 monoclonal antibody in nude mice bearing colon cancer xenografts. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 1997;12:55–62. doi: 10.1089/cbr.1997.12.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusckowski M, Qu T, Pullman J, et al. Inflammation and infection imaging with a 99mTc-neutrophil elastase inhibitor in monkeys. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:363–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schibli R, La Bella R, Alberto R, et al. Influence of the denticity of ligand systems on the in vitro and in vivo behavior of 99mTc(I)-tricarbonyl complexes: a hint for the future functionalization of biomolecules. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:345–351. doi: 10.1021/bc990127h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderheyden JL, Gofinch S, Srinvasan A, et al. Preparation and characteriztion of Re-186 labeled NR-CO-02 F(ab)2: a new anti-CEA antibody fragment for radioimmunotherapy (abstract) J Nucl Med. 1989;30:793. [Google Scholar]

- Visser GW, Gerretsen M, Herscheid JD, et al. Labeling of monoclonal antibodies with rhenium-186 using the MAG3 chelate for radioimmunotherapy of cancer: a technical protocol. J Nucl Med. 1993;34:1953–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnard P, Jr, Chang F, Rusckowski M, et al. Preparation and use of NHS-MAG3 for technetium-99m labeling of DNA. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:425–432. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn KR, Buchsbaum DJ, Chaudhuri TR, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of gene transfer using a reporter receptor imaged with a high-affinity peptide radiolabeled with 99mTc or 188Re. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:887–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckier LS, Dohan O, Li Y, et al. Kinetics of perrhenate uptake and comparative biodistribution of perrhenate, pertechnetate, and iodide by NaI symporter-expressing tissues in vivo. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:500–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]