Abstract

Context

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers face exposure to combat during wars across the globe. The health impact of traumatic war experiences has not been adequately assessed across the lifetime of these veterans.

Objective

Identify the role of traumatic war experiences in predicting post-war nervous and physical disease and mortality using archival data from military and medical records of veterans from the Civil War.

Design

An archival examination of military and medical records of Civil War veterans was conducted. Degree of trauma experienced (POW experience, percentage of company killed, being wounded, early age at enlistment), signs of lifetime physician-diagnosed disease, and age at death were recorded.

Setting and Participants

US Pension board surgeons conducted standardized medical examinations of Civil War veterans over their post-war lifetimes. Military records of 17,700 Civil War veterans were matched to post-war medical records.

Main Outcome Measures

Signs of physician-diagnosed disease including cardiac, gastrointestinal (GI), and nervous disease, and number of unique ailments within each disease; mortality.

Results

Military trauma was related to signs of disease and mortality. Greater percentage of company killed was associated with signs of post-war cardiac and GI disease (IRR=1.34, p<.02), co-morbid nervous and physical disease (IRR=1.51, p<.005), and greater number of unique ailments within each disease (IRR=1.14, p<.01). Younger soldiers (≤18 years old), compared to older enlistees (> 30 years old), showed higher mortality risk (HR=1.52, p<.005), signs of co-morbid nervous and physical disease (IRR=1.93, p<.005), and a greater number of unique ailments within each disease (IRR=1.32, p<.005), controlling for length of time lived and other covariates.

Conclusions

Greater exposure to death of military comrades and younger exposure to war trauma was related to signs of physician-diagnosed cardiac, GI and nervous disease, and a greater number of unique disease ailments across the life of Civil War veterans. Physiological mechanisms by which trauma might result in disease are discussed.

Keywords: combat exposure, Civil War Veterans, war trauma, physical health, mental health

War is particularly traumatic for soldiers because it often involves intimate violence, including witnessing death through direct combat, viewing the enemy before or after killing them, and watching friends and comrades die.1 Heavy combat exposure, seeing comrades injured, witnessing death, and Prisoner of War (POW) experience are traumatic above and beyond the amount of time spent in military service or other military events.2, 3 Young adults exposed to military combat may also be at greater risk than their older peers. Vietnam Veterans who were 19 years of age or younger during the war were significantly more likely to have substance abuse problems, criminal activity, employment difficulties, and problems with social relationships after discharge,4 and long-term distress and symptomatology is higher among Vietnam veterans who entered military service at a younger age. 5

Many investigators have examined the mental health consequences of exposure to war trauma and found substantial post-war psychiatric difficulties among veterans.6–10 Research has also linked war trauma and physical health outcomes,11 including an increase in negative physical symptom reporting,12–15 chronic illness, and death.12,16 Traumatic war exposure has also been linked to specific self-reported and objective health problems such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension6, 17–20 and gastrointestinal (GI) disorders.8, 21, 22 Nonetheless, although literature detailing patterns of physical health problems among aging veterans has grown,23 it has suffered from a heavy reliance on self-report measures of either military trauma 8, 12, 14, 22, 24–26 or health.6, 12–15, 18–21, 24–26 While some researchers have examined military and medical records on a small sample of servicemen,27 their aim has been to examine clusters of post-war syndromes rather than link multiple traumas with specific physical disease states. Up to this point there has been no examination of the health effects of multiple war traumas using both well-documented military service records and objective health data over veterans’ lifetimes.

Outlining specific combat experiences (e.g., being wounded, taken as a POW, witnessing death) is critical in determining what part of the traumatic experience is particularly detrimental to health. Some have theorized, based on self-reports of intense or prolonged combat, that intimate violence may be the most devastating mentally and physically,28–30 and that exposure to war atrocities may be more traumatic than the threat of personal death that accompanies combat.31

During the Civil War, soldiers were particularly vulnerable to intimate violence. Family members and friends were often assigned to the same company of around 100 men, who were not replaced as they died. When companies suffered substantial losses, survivors were left with few remaining friends or male family members.32 Soldiers readily identified with the enemy (who were sometimes from the same state or county), making the sight of mutilated corpses even more gruesome.1 Although guns and cannons were used, frontal assault was common, and hand-to-hand combat, with no trenches or barriers, resulted in row after row of dead bodies and the sight of comrades blown apart.32 Unlike in other documented wars, young adolescents and older men were allowed entry into military service (ranging from under 10 to over 70 years).32 Overall, the Civil War qualifies as one of the bloodiest in American history, exposing thousands to incomparable traumatic experiences.32, 33 If intimate violence is particularly detrimental, increased exposure to such violence should consistently predict negative health outcomes.

There is great interest in the Civil War. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., which house the original military and medical records, report that the Civil War is the most researched and written about war in all of history. The current study examines the relationship between traumatic war exposure and health outcomes directly using objective health and trauma data collected from a sample of Union Army Civil War veterans with the goal of parsing the effects of various war experiences on health. We hypothesized that severity of traumatic war exposure (e.g., greater exposure to death, younger age at entry) would predict signs of three physician-documented diseases that have been linked theoretically and empirically to traumatic life experiences: cardiac, GI, and mental health disorders,11 and a greater number of unique ailments across a veteran’s post-war lifetime.

METHODS

Sample Selection and Data Sources

Data were collected as part of an effort to amass the largest, most comprehensive collection of electronic Civil War data files transcribed from their original written records. This project, Early Indicators of Later Work Levels, Disease, and Death (EI), is sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.34 Out of 20,000 possible companies from the Descriptive Roll books at the National Archives, 303 companies of Union Army recruits were randomly selected. Military service records and pension file information was sought on every recruit in each company, resulting in a final sample of 35,730. The government went to great lengths to ensure the validity and precision of military records.35 Pension files contain post-war medical records and standardized physical examinations until the recruit’s death (called Surgeon’s Certificates) completed by government physicians certifying the veteran’s health and disability status.36 Those recruits who died during the war or deserted did not generate a Surgeon’s Certificate.36 Thus, not all recruits’ military files could be linked to their medical records. Of the sample of 35,730 recruits, 17,700 participants were linked, and among these, veterans with complete data on key study variables were selected for analyses (n=16,200). The majority of excluded cases (n=1,442) were missing age at death, a crucial study variable that necessitated their exclusion. Consistent with pension law, the sample is further restricted to the 15,027 recruits who lived until 1890 or later, when physicians could diagnose non-service connected disease. Prior to 1890, physicians only diagnosed service-connected illness and wounds to avoid paying pensions for conditions unrelated to military service. Recruits who died before 1890 were slightly older at enlistment (phi2=.024, p<.005). Effect sizes (phi2) for the remaining study variables, although statistically significant, were extremely small, ranging from .03% for POW status to .8% for enlistment year. Statistical models fit to the full (16,200) and reduced (15,027) samples were comparable, and inferential conclusions remain unchanged.

All recruits were examined by physicians and screened for health problems before entering military service. A substantial number of volunteer servicemen were rejected from military duty due to illness, physical disabilities, body size, and other unclassified problems, suggesting a healthy baseline sample.37 One might hypothesize that recruits who enlisted early in the war were healthier, more robust volunteers than later in the war effort. Also, early volunteers may have faced more rigorous health screening than recruits who entered during later years, when the draft made service unavoidable. An indicator variable reflecting early (1860–1861) versus later (1862–1864) enlistment was created as a rough proxy for baseline health status and to control for the possibility of differential health screening over time.

Data Collection

The EI project developed its own data collection software designed for entering information available from data sources housed at the National Archives. The sources of data included Military records, which contained detailed accounts of military service, including enlistment and discharge dates, age at enlistment, geographic location of company, and many other variables, and Pension files, which contained birth information, number of self-reported disease claims, and health records (i.e., Surgeon’s Certificates) after the recruit’s military service was complete, among other variables. These datasets were transcribed, cleaned and cross-referenced with each other so that the accuracy and completeness of a recruit’s file would be at the highest possible level. Careful data standardization and controls were instituted to insure quality information. Trained researchers transferred written records into a standardized computer database utilizing automated controls, such as upper and lower bounds on fields, acceptable coded values for fields with a list of possible predetermined values, two-field checks, and dates had to make sense (i.e., no death before birth year). Medical and occupational dictionaries from the 19th and 20th centuries were available for reference by the data coders. De novo sampling was used as a quality control technique. A random sample of 5–10% of recruits were drawn from each company and re-entered. Differences calculated between the original and de novo sample were classified as follows: incorrect entries (misread word, data entered in the wrong screen; 2.3%), omission errors (random inadvertent skipping of information; 4.0%), numerical errors (0.2%), and rating errors (skipped or misread rating when coding disease categories; 0.3%).

Predictor Variables

Age at Enlistment

Age at first enlistment was obtained from military records and ranged from 9 years – 71 years old. Because younger age at first enlistment was predicted to be more stressful and lead to more negative health outcomes over the lifespan, this variable was categorized into five age-ranged groups of approximately equal size to highlight the effect of younger ages: 9–17 years old (n=3013); 18–20 years old (n=3694); 21–25 years old (n=3435); 26–30 years old (n=2225); and over 31 years (n=2660). The oldest group of recruits (≥31 years) was used as the reference group in all analyses.

Age at Death

Age at death was obtained primarily from death certificates in the veteran’s file. If no death certificate was present, death date was gleaned from pension records, military notice of death records, or other correspondence. Age at death was used in continuous form as a covariate in some analyses and as an outcome in other analyses. Additionally, it was stratified (9–49 years=1; 50–64 years=2; 65–74 years=3; 75–104 years=4) in order to compare signs of disease across individuals in the same age cohort.

Socioeconomic Status

The profession a recruit claimed gives a rough estimate of his socioeconomic status (SES) during the Civil War era. Six categories of professions were identified: farmers, professionals, artisans, service workers, laborers and unproductive persons (e.g., those involved in scholarly activities). SES was represented as a series of five indicator variables with “farmer” serving as the reference group.

Trauma History

History of traumatic events experienced by each recruit was gathered from military records. Traumatic exposure was operationalized as POW experience, being wounded, early age at enlistment, and the percentage of soldiers who died in a recruit’s company (i.e., percentage of company killed). Percentage of company killed was divided into quartiles; the lowest quartile served as the reference group. POW experience was originally cast as a 3 level variable (never, prior to 1864, 1864 or later) due to more severe conditions in POW camps later in the war effort. However, results in the latter two groups were the same, so they were combined for the sake of parsimony.

Health Outcomes

Health history was gathered from the Pension files. In order to receive a military pension, veterans were required to attend a physical examination for each illness or disease claim. Thus, medical exams were not conducted annually but only when a new claim was presented or an adjustment in an existing claim was necessary. Every veteran had at least 1 exam, with a maximum of 30 exams and a median of 4 exams (79% of the veterans had 7 or fewer exams). The government Pension Board required that each exam be conducted by three physicians who were required to come to a consensus before a diagnosis was made.36 The original medical diagnoses were entered into the EI data collection software system within “disease screens.” These screens were divided by organ systems and provided non-medical data inputters a framework with which to transfer the medical data into a database. Medical doctors on the EI project carefully re-coded the data into a classification system that corresponds to current medical diagnoses so the data can be equated to modern-day ailments. Diagnoses that were recorded include only medically-reliable data. At no time in the process of data entry did the data inputters or cleaners make medical judgments. Only diagnoses representing signs of disease were examined in this study, and were selected based on indicators of abnormal, chronic conditions.

Post-war Signs of Disease

A veteran was classified as having signs of cardiovascular, GI, or nervous disease if he was ever diagnosed with one or more ailments from the categories below in his post-war lifetime. Signs of physical or nervous disease, alone or in combination, diagnosed in any exam over the recruit’s post-war lifetime, were coded into one six-level categorical variable: no disease, cardiac only, GI only, both cardiac and GI, nervous only, and nervous disease with cardiac and/or GI disease.

Cardiac disease ailments included irregular pulse, regurgitant or stenotic murmurs, heart enlargement, arteriosclerosis, edema, cyanosis, dyspnoea, and impaired circulation. Further coding of these disease symptoms according to the International Classification of Diseases Version 9 (ICD-9) places them within the general category of circulatory disorders.38

GI disease ailments included diarrhea, dyspepsia, pain, ulcer, vomiting food or blood, abdominal tenderness, dysphagia, and malassimiliation, among others. Further coding of these disease symptoms according to the ICD-9 places them within the general category of digestive disorders.38

Nervous disease ailments included paranoia, psychosis, hallucinations, illusions, insomnia, confusion, hysteria, memory problems, delusions, and violent behavior. In addition, many symptoms that fit within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV)39 criteria B, C, and D classification of PTSD were diagnosed as “nervous disease” during the Civil War era. Nervous ailments also included other mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, neurosis, suicidal ideation, antisocial behavior, attention deficits, hysteria, insanity, and mania, as well as physical ailments of the nervous system including trouble with balance, incoordination, aphasia, paralysis, tremor, hyperaesthesia, vertigo, headaches, epilepsy and memory loss.

Number of Unique Disease Ailments

The number of disease ailments is a count of the number of unique cardiac, GI and nervous ailments across all medical exams over the veteran’s post-war lifetime. Each unique disease ailment was counted only once, when the veteran was first diagnosed with the condition.

Data Analysis

Although companies were randomly sampled, individual-level data were used in this report. As such, men were considered to be clustered within companies and regression models were estimated using methods allowing for dependence among observations within clusters.40,41 The post-war lifetime presence of disease (a six-level categorical variable) was analyzed using a maximum likelihood multinomial logistic regression; the number of unique disease ailments was analyzed using a negative binomial regression (a Poisson with overdispersion), and mortality risk was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model. This analysis provides estimates of the risk of mortality for veterans with and without traumatic war exposure. Effect sizes (and 95% confidence intervals) are estimated using incidence risk ratios (IRR) for the post-war signs of disease and the number of unique disease ailments, and hazard ratios for mortality risk. All analyses were performed using STATA, version 8.0 (Stata Corp).

Regression models include indicator variables representing SES, year of enlistment, and age at death to ensure the key study variables (trauma exposure and age at enlistment) were adjusted for these covariates. For the sake of parsimony, we use age of death as a continuous covariate in the analyses in order to insure that greater health problems were not simply a result of living longer (and thus having a greater chance of developing health problems).

Theoretically relevant interactions were screened for inclusion in the multivariable models. Specifically, interactions among key study variables were evaluated to determine whether the effect of trauma on signs of disease depended on other exposures (e.g., the effect of age at enlistment might be magnified by exposure to trauma as measured by POW status, percentage of company killed, or being wounded). Interaction terms reaching the p=.05 level of significance are reported.

RESULTS

Analysis of Nonparticipants

Nonparticipants were defined as recruits who were in the total military sample and had data on predictor variables (e.g., POW experience) but whose medical records could not be linked during data collection (n=18,027). Previous analyses utilizing this data set has established that nonparticipants were significantly more likely to be dead or deserters so that a link between their military service and medical records after the war could not be established.34 Table 1 provides a description of participants and nonparticipants using all study variables. Although there were statistically significant differences between participants and nonparticipants, we note that standardized effect sizes (Phi2) were small, ranging from .002% for POW status to 5.7% for occupation. One exception was age at death, where only 8,623 of the nonparticipants had this information available and this group died quite young (M=37.1 years) when compared to participants (M=72.5 years), p<.005.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for all Study Variables by Participant Status

| Participantsa | Nonparticipants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariatesb | M | SD | % | M | SD | % |

| SES: Profession upon entry** | ||||||

| Farmer | 64.7 | 43.9 | ||||

| Professional | 10.3 | 10.1 | ||||

| Artisan | 15.0 | 20.9 | ||||

| Service | 2.9 | 5.5 | ||||

| Laborer | 6.7 | 18.9 | ||||

| Unproductive | 0.2 | 0.5 | ||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 (n=17,633) | ||||

| Age at death (years)*** | 72.5 | 10.13 | 37.1 | 18.6 | (n=8,623) | |

| Categorical Age at death** | ||||||

| 9–49 years | 1.7 | 78.0 | ||||

| 50–64 years | 20.1 | 9.6 | ||||

| 65–74 years | 32.9 | 5.9 | ||||

| 75–104 years | 45.2 | 6.5 | ||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 (n=8,623) | ||||

| Year of Enlistment*** | ||||||

| 1860–1861 | 62.3 | 58.1 | ||||

| 1862–1865 | 37.7 | 42.0 | ||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 (n=17,978) | ||||

| Participantsa | Nonparticipants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure Variables | M | SD | % | M | SD | % |

| Age at enlistment (years)** | 23.6 | 7.3 | 25.1 | 8.1 | (n=17,978) | |

| Categorical Age at enlistment*** | ||||||

| 9–17 years | 20.1 | 15.7 | ||||

| 18–20 years | 24.6 | 22.0 | ||||

| 21–25 years | 22.7 | 24.6 | ||||

| 25–30 years | 14.8 | 14.5 | ||||

| 31 years & older | 17.7 | 23.3 | ||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 (n=17, 978) | ||||

| Company Killed (percent)*** | 9.8 | 6.7 | 10.3 | 6.9 | (n=18,027) | |

| Quartiles of Company Killed** | ||||||

| 0 – 4.16% | 25.5 | 23.6 | ||||

| 4.17% – 9.19% | 25.0 | 23.9 | ||||

| 9.20% – 14.10% | 24.7 | 25.0 | ||||

| 14.20% – 30.96% | 24.9 | 27.4 | ||||

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 (n=18,027) | ||||

| Length of Service (months)** | 26.2 | 18.5 | 27.4 | 15.2 | (n=17,828) | |

| % POW** | 8.7 | 9.5 (n=18,027) | ||||

| % Wounded** * | 33.2 | 20.0 (n=18,027) | ||||

| Participantsa | Nonparticipants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | M | SD | % | M | SD | % |

| Postwar Lifetime Signs of Disease | ||||||

| No Disease | 15.0 | |||||

| Signs of Physical Disease | ||||||

| GI ailments only | 5.79 | |||||

| Cardiac ailments only | 18.0 | |||||

| Cardiac and GI ailments | 17.4 | |||||

| Signs of Mental Disease | ||||||

| Nervous ailments only | 5.1 | |||||

| Co-Morbid Physical and Mental Ailments | 38.8 | |||||

| Number of Unique Ailmentsc | Median | Min | Max | |||

| 4.3 | 0 | 28 | ||||

Note: M=Mean; SD=Standard Deviation; Percent (%) = column percent

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

n= 15,027; the number of nonparticipants with data is indicated for each variable.

Chi Square analyses conducted on dichotomous and categorical variables; unpaired t-test performed on age at enlistment, age at death, length of service, and percentage of company killed. Effect size estimates ranged from .0013%–.6880% for the Point Biserial2 correlations and ranged from .0002%–.0569% for the Phi2 Coefficients.

The total number of unique cardiac, GI, and nervous ailments that a veteran was diagnosed with over his post-war lifetime.

Signs of Post-war Disease

Table 2 describes the association between disease outcomes and the key study variables. Relative to the oldest enlistees, the youngest were more likely to be diagnosed with signs of cardiovascular disease alone and in combination with signs of GI disease and were at greater risk of presenting with signs of co-morbid physical and nervous disease. There was no association between age at enlistment and the presence of nervous disease alone.

Table 2.

Relationship between Age at Enlistment, Traumatic War Exposure, and Signs of Cardiac, GI or Nervous Disease.

| Relative to No Signs of Disease Conditiona | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variablesb | GI Only (n=870) | Cardio Only (n=2,699) | Cardio and GI (n=2,615) | Nervous Only (n=762) | Nervous & Cardio/GI (n=5,835) | |||||

| Age at Enlistment | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI |

| Age 9–17 years | 1.07 | 0.82, 1.39 | 1.44*** | 1.18, 1.77 | 1.60*** | 1.29, 1.98 | 0.95 | 0.72, 1.25 | 1.93*** | 1.61, 2.30 |

| Age 18–20 years | 1.21 | 0.95, 1.54 | 1.38** | 1.15, 1.67 | 1.63*** | 1.33, 2.01 | 1.00 | 0.77, 1.32 | 1.90*** | 1.61, 2.24 |

| Age 21–25 years | 1.23 | 0.95, 1.59 | 1.35** | 1.13, 1.60 | 1.55*** | 1.27, 1,89 | 0.99 | 0.78, 1.26 | 1.77*** | 1.50, 2.09 |

| Age 26–30 years | 1.42** | 1.09, 1.86 | 1.43*** | 1.18, 1.73 | 1.47*** | 1.21, 1.78 | 1.04 | 0.77, 1.40 | 1.71*** | 1.43, 2.04 |

| Age ≥ 31 years | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | |||||

| POW (1=yes) | 0.92 | 0.67, 1.27 | 1.04 | 0.83, 1.32 | 1.06 | 0.85, 1.33 | 0.96 | 0.73, 1.27 | 1.23* | 1.01, 1.51 |

| Ever wounded (1=yes) | 0.45*** | 0.37, 0.54 | 0.63*** | 0.56, 0.72 | 0.46*** | 0.40, 0.52 | 1.64*** | 1.39, 1.93 | 0.67*** | 0.60, 0.75 |

| % Company Killed | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI | IRR | 95% CI |

| 1st quartile | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | ----- | |||||

| 2nd quartile | 1.30* | 1.02, 1.64 | 1.31** | 1.08, 1.59 | 1.34* | 1.07, 1.68 | 0.99 | 0.78, 1.26 | 1.51*** | 1.25, 1.84 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.20 | 0.94, 1.53 | 1.18† | 0.98, 1.43 | 1.32** | 1.07, 1.63 | 1.15 | 0.92, 1.44 | 1.39*** | 1.16, 1.67 |

| 4th quartile | 1.13 | 0.88, 1.43 | 1.04 | 0.87, 1.25 | 1.32* | 1.05, 1.65 | 1.05 | 0.84, 1.30 | 1.33** | 1.09, 1.62 |

-- reference group N=15,027

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.005

IRR for one or more lifetime disease sign relative to No Disease Signs (n=2,246)

Effect sizes for predictor variables are adjusted for effects of listed predictors, SES, age at death, and year of enlistment.

Relative to the lowest quartile of the percentage of company killed, veterans in the second quartile were at increased risk of signs of GI and cardiac disease alone. Veterans in all quartiles of company killed, relative to the lowest, were at greater risk of developing signs of co-morbid GI and cardiac disease. Veterans in all quartiles of company killed, relative to the lowest, were at greater risk of developing signs of co-morbid physical and nervous disease. There was no association between percentage of company killed and signs of nervous disease alone.

POW experience was not associated with signs of physical or nervous disease alone, but was associated with an increased risk of co-morbid physical and nervous disease. Being wounded was associated with an increased risk of nervous disease alone, a decreased risk of physical disease, and signs of co-morbid physical and nervous disease.

There was an interaction between percentage of company killed (highest quartile relative to the lowest) and being wounded for signs of physical disease (p<.05) and for signs of co-morbid physical and nervous disease (p<.05). Among recruits who were wounded during the war, there was no association between percentage of company killed and signs of disease. In contrast, among recruits who were not wounded in the war, those in the highest quartile of company killed were at increased risk of physical disease diagnosis (IRR=1.33, p<.05) and were at increased risk of signs of co-morbid physical and nervous disease (IRR=1.36, p<.05).

Number of Post-war Unique Ailments

The youngest veterans at enlistment were at risk of developing a greater number of unique post-war ailments than their older peers. This pattern continues through age 30 years with younger enlistees at greatest risk of being diagnosed with more unique disease ailments when compared to older enlistees (Table 3). Relative to the lowest quartile of company killed, recruits in the upper quartiles were diagnosed with more ailments. POW experience was not associated with the number of unique disease ailments and being wounded was associated with fewer unique disease ailments.

Table 3.

Relationship between Age at Enlistment, Traumatic War Exposure, and Development of Unique Cardiovascular, GI, and Nervous Ailments.

| Predictor Variablesb | ||

| Age at Enlistment | IRRa | 95% CI |

| 9–17 years | 1.32*** | 1.25, 1.38 |

| 18–20 years | 1.28*** | 1.22, 1.35 |

| 21–25 years | 1.28*** | 1.22, 1.34 |

| 26–30 years | 1.23*** | 1.17, 1.38 |

| ≥ 31 years | ----- | |

| POW (1=yes) | 1.02 | 0.96, 1.09 |

| Ever wounded (1=yes) | 0.87*** | 0.84, 0.89 |

| % Company killed | ||

| 1st quartile | ----- | |

| 2nd quartile | 1.11** | 1.04, 1.19 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.12** | 1.04, 1.20 |

| 4th quartile | 1.14*** | 1.06, 1.23 |

-- reference group n=15027

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.005

Incidence rate ratio predicting number of unique cardiac, GI and nervous ailments that a veteran developed over his post-war lifetime.

Effect sizes for predictor variables are adjusted for effects of listed predictors, SES, age at death, and year of enlistment.

Mortality

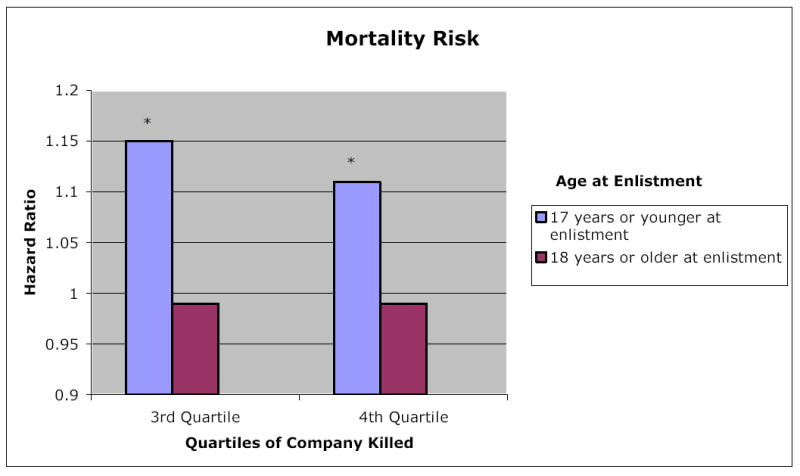

Mortality risk was significantly associated with age at entry into service (Table 4). Recruits who were youngest at enlistment (<18 years old) had the greatest risk for early death (hazards ratio [HR]=1.52, p<.005). This pattern continued across each age category, with younger enlistees at greater risk of early death compared to older enlistees. POW experience was associated with an increased risk of early death (HR=1.07, p<.005). There were two significant interactions involving age at enlistment and the percentage of company killed for both the third (p<.03) and fourth (p<.05) quartiles relative to the first. Among recruits who were less than 18 years old at first enlistment, having a higher percentage of one’s company killed was associated with an increased risk of early death (3rd quartile: HR=1.15, p<.05; 4th quartile: HR=1.11, p<.05; see Figure 1). Among recruits who were 18 years or older at first enlistment, there was no association between the percentage of company killed and mortality.

Table 4.

Relationship between Traumatic War Exposure and Mortality

| Predictor Variablesb | ||

| Age at Enlistment | Relative Hazarda | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Age 9–17 years | 1.52*** | 1.44, 1.60 |

| Age 18–20 years | 1.31*** | 1.26, 1.37 |

| Age 21–25 years | 1.29*** | 1.23, 1.35 |

| Age 26–30 years | 1.20*** | 1.44, 1.26 |

| Age ≥ 31 years | ----- | |

| POW (1=yes; 0=no) | 1.07* | 1.01, 1.12 |

| Ever wounded (1=yes; 0=no) | 1.03† | 0.99, 1.07 |

| % Company killed | ||

| 1st quartile | ----- | |

| 2nd quartile | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.07 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.07 |

| 4th quartile | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.06 |

-- reference group (n=15,027)

p<.08;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.005

Hazard Ratios.

Effect sizes for predictor variables are adjusted for effects of listed predictors, SES, age at death, and year of enlistment.

Figure 1.

Mortality Risk: Interaction Between Age at Enlistment and Percentage of Company Killed

(n=15,027) *p<.05

Confidence Intervals: 3rd quartile for 17 years and younger 1.06 ≤ 1.15 ≤ 1.24;

3rd quartile for 18 years and older .94 ≤ .99 ≤ 1.05;

4th quartile for 17 years and younger 1.04 ≤ 1.11 ≤ 1.18

4th quartile for 18 years and older .95 ≤ .99 ≤ 1.05

COMMENT

We demonstrate substantial long-term health effects of traumatic war experiences among Civil War soldiers. While war trauma was moderately associated with developing signs of GI, cardiac, or nervous disease alone, it was strongly associated with developing signs of nervous and physical disease in combination. One objective measure of intimate violence, percentage of company killed, predicted a 51% increased incidence in signs of physician-diagnosed cardiac, GI and nervous disease, and a 14% increased incidence of unique disease ailments. Percentage of company killed is likely a powerful variable because it serves as a proxy for a variety of traumatic stressors such as witnessing death or dismemberment, handling dead bodies, traumatic loss of comrades, one’s own imminent death, killing others, and being helpless to prevent others’ deaths. In addition, veterans who were younger at enlistment had a 93% increased risk of developing signs of co-morbid physical and nervous disease and experienced a 32% increased incidence of unique disease ailments. Young veterans (under 18 years at enlistment) were at increased risk of early death if they witnessed more death during the war. In all analyses, we controlled for age at death, ensuring that these results were not simply due to the fact that younger men lived longer and thus had more opportunity to develop disease. We did not find any interactions between age at enlistment and most war trauma variables, suggesting that the effect of age at enlistment on health outcomes was not exacerbated by being taken POW or being wounded. In addition, younger recruits were at greater risk of contracting unique disease ailments than older men. It is also possible that those healthy enough to enlist in the Civil War at an older age may have been hardier individuals, leading to their decreased morbidity and mortality.42

Before entering military service, all recruits in this sample were screened for health problems and deemed unfit for service if they were ill or disabled.37 This initial screening suggests that it was the military experience, rather than some pre-existing medical condition, that accounted for the health effects observed. The possibility of differential health screening over the course of the war was also accounted for in our analyses. When examining both mental and physical health outcomes after exposure to war trauma, we found different trauma profiles predicted each. For example, while being wounded increased the incidence of developing signs of nervous disease by 64%, wounded soldiers were significantly less likely to develop signs of GI or cardiac disease alone. The pattern of findings suggest that those veterans who survived being wounded may have been particularly hardy given the unsanitary conditions of the war.43

POW experience predicted signs of co-morbid physical and nervous disease and mortality. This likely reflects the traumatic psychological impact that spending time in war camps may have had on soldiers, and bolsters our conclusion that although physical hardiness may have acted as a buffer for physical disease, it did not protect against the ill effects of war on mental health.

Although self-reported disease is not the focus of this paper, it is noteworthy that veterans who experienced more traumatic wartime experiences were significantly more likely to report an increased number of disease ailments. For example, POW experience, being wounded, increased percentage of company killed, and younger age at enlistment were associated with greater numbers of self-reported disease ailments.

Many studies link emotional stress, such as combat, to mental health problems.1–3,7–10, 13, 14, 24–31, 44 Recent literature on the impact of trauma on health has suggested that psychological response, specifically PTSD, mediates the relationship between trauma exposure and physical health outcomes.11 Unfortunately we are unable to examine this relationship in this archival dataset because we do not have clear temporal information on the development of nervous, GI or cardiac ailments (e.g., veterans may have presented with all ailments simultaneously rather than sequentially). In addition, the Civil War era preceded the recognition of a PTSD diagnosis.

Researchers have also hypothesized mechanisms by which emotional stress is linked to physical disease.6,12,13,16–21,24,25, 45–50 Allostatic load theory47 postulates a neurochemical response via the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in response to acute stress. Although this may be adaptive when stressors are met and resolved quickly, over periods of chronic stress, these body systems can become either unable to mount an appropriate response or become overly sensitive,44 overloaded by the normal cascade of stress hormones. For example, over periods of chronic stress (i.e., battlefield events or witnessing death), there may be chronic cardiovascular activation that leads to elevated blood pressure and atherosclerotic development. Permanent changes in the structure and function of the stress regulatory systems are a likely mechanism leading to increased morbidity and mortality in individuals exposed to intimate violence.

Individuals who experience severe, prolonged stress may engage in compensatory negative health behaviors such as overeating, smoking, drug abuse or other harmful habits that may, in turn, lead to subsequent physical disease. Unfortunately, reliable information about drug use, smoking, and obesity is not available for the men in this study. However, Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as a predictor of mortality in a subsample of 377 Civil War veterans from this data set and BMI appears not to be as significant a predictor of cardiac disease during the Civil War era as in modern time.42

This study has some limitations. While these data have been carefully accumulated, coded and analyzed, it is recognized that archival medical data, by definition, is not interchangeable with modern medical diagnoses. Due to the lack of sophistication and medical equipment during the Civil War era, diagnoses of ailments cannot be assumed to coincide with modern diagnoses of physical and mental disease. Because not all signs and symptoms of cardiovascular heart disease or PTSD were assessed, veterans are not assumed to have had these diagnoses. Nonetheless, although we are unable construct current medical diagnoses as outcome variables using this dataset, Civil War era physicians were able to recognize and record signs of physical and mental disease that are indicative of modern diagnoses. Similar to recent studies that have found evidence of cardiovascular 6, 17–20 and GI disease 21,22 and PTSD 6–10 post-war, we found that combat exposure was related to increased self-reports of negative physical symptoms, and physician-diagnosed signs of cardiac (e.g., arteriosclerosis), GI disease (e.g., ulcer) and mental health problems (e.g., depression).

Conclusion

The current study brings us a step closer to understanding the long-term health consequences of traumatic war experiences. Not only was the Civil War the beginning of a recognition of mental health problems caused by war, labeled “irritable heart syndrome”, but many recognize the Civil War as laying the roots of modern cardiology.51

Our analysis is the first to use objective military and medical records to demonstrate the development of post-war disease ailments over the life course among veterans of any war. We found strong relations between traumatic exposure (e.g., witnessing a larger percentage of company death), co-morbid disease, mental health ailments, and early death. Despite the age of the dataset, there have been few other opportunities to examine standardized medical exams over a post-war period until all soldiers have died. In fact, modern data sets could not provide this kind of information. Unfortunately, it is likely that the deleterious health effects seen in a war conducted over 130 years ago are applicable to the health and well-being of soldiers fighting wars in the 21st century, as recent studies have suggested.9,15, 52

Acknowledgments

Project funding provided by grant P01 AG10120 from the National Institutes on Aging as a subgrant from the Center for Population Economics (CPE) at the University of Chicago and the National Bureau of Economics. We thank Joey Burton, Dora Costa, Louis Nguyen, Sven Wilson, Werner Troesken, and Chulhee Lee for providing assistance with the Union Army archival data system.

References

- 1.Hendin H, Haas A. Posttraumatic Stress Disorders in veterans of early American wars. Psychohistory Review. 1984;12(4):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escobar JI, Randolph ET, Puente G, Spiwak F, Asamen JK, Hill M, Hough RL. Post-traumatic stress disorder in Hispanic Vietnam veterans: clinical phenomenology and sociocultural characteristics. J Nervous & Mental Disease. 1983;171:585–596. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1990. Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harmless A. Developmental impact of combat exposure: comparison of adolescent and adult Vietnam veterans. Smith College Studies in Social Work. 1990 Mar;60(2):185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver RC, Holman EA, Hawkins NA, Butler JM. Unpublished Manuscript, UC Irvine. 2005. Long-term effects of combat exposure on young soldiers. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falger PR, Op den Velde W, Hovens JE, et al. Current posttraumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Dutch Resistance veterans from World War II. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics. 1992;57(4):164–171. doi: 10.1159/000288594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ursano RJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jan 10;346(2):130–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200201103460213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford JD, Campbell KA, Storzbach D, Binder LM, Anger WK, Rohlman DS. Posttraumatic stress symptomatology is associated with unexplained illness attributed to Persian Gulf War military service. . Psychosomatic Med. 2001;63(5):842–849. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200109000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan: mental health problems, and barriers to care. NEJM. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koren D, Norman D, Cohen A, Berman J, Klein EM. Increased PTSD risk with combat-related injury: a matched comparison study of injured and uninjured soldiers experiencing the same combat events. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:276–282. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnurr PP, Green BL. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. Trauma and health: Physical health consequences of exposure to extreme stress. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elder GH, Jr, Shanahan MJ, Clipp EC. Linking combat and physical health: the legacy of World War II in men’s lives. Am J Psychiatry Mar. 1997;154(3):330–336. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner AW, Wolfe J, Rotnitsky A, Proctor SP, Erickson DJ. An investigation of the impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on physical health. J Trauma Stress Jan. 2000;13(1):41–55. doi: 10.1023/A:1007716813407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King DW, King LA, Foy DW, Keane JM, Fairbank JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of female and male Vietnam Veterans: risk factors, war-zone stressors, and resilience-recovery variables. J Abnormal Psychol. 1999;108:164–170. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmons RK, Maconochie N, Doyle P. Self-reported ill health in male UK Gulf War veterans: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creasey H, Sulway MR, Dent O, Broe GA, Jorm A, Tennant C. Is experience as a prisoner of war a risk factor for accelerated age-related illness and disability? J Am Geriatrics Society Jan. 1999;47(1):60–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchard EB. Elevated basal levels of cardiovascular responses in Vietnam veterans with PTSD: a health problem in the making? J Anxiety Disorders. 1990;4:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ullman SE, Siegel JM. Traumatic events and physical health in a community sample. J Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:703–720. doi: 10.1007/BF02104098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkow B. Psychosocial and central nervous influences in primary hypertension. Circulation. 1987;76(Suppl 1):110–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Litz BT, Keane TM, Fisher L, Marx B, Monaco V. Physical complaints in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5:131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goulston KJ, Dent OF, Chapuis PH, et al. Gastrointestinal morbidity among World-War-2 Prisoners of War - 40 years on. Med J Australia. 1985;143(1):6–10. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1985.tb122757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnurr PP, Spiro A, III, Paris AH. Physician-diagnosed medical disorders in relation to PTSD symptoms in older military veterans. Health Psychol. 2000;19(1):91–97. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyams KC, Wignall S, Roswell R. War syndromes and their evaluations: from the U.S. Civil War to the Persian Gulf War. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1996;125:398–405. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-5-199609010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnurr PP, Spiro A. Combat exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and health behaviors as predictors of self-reported physical health in older veterans. J Nervous & Mental Disease. 1999;187:353–359. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boscarino JA. Diseases among men 20 years after exposure to severe stress: implications for clinical research and medical care. Psychosomatic Med. 1997;59:605–614. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199711000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Sengupta A, Jankowski MK, Holmes T. PTSD and utilization of medical treatment services among male Vietnam veterans. J Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188:496–504. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones E, Hodgins-Vermaas R, McCartney H, Everitt B, Beech C, Poynter D, Palmer I, Hyams K, Wessely S. Post-combat syndromes from the Boer war to the Gulf war: a cluster analysis of their nature and attribution. BMJ. 2002;324:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7333.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elder GH, Clipp EC. Combat experience and emotional health: impairment and resilience in later life. J Personality. Special Issue: Long-term stability and change in personality. 1989 Jun;57(2):311–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler AB, Vaitkus MA, Martin JA. Combat exposure and posttraumatic stress symptomatology among US soldiers deployed to the Gulf war. Military Psychol. 1996;8:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontana A, Rosenheck R. A model of war zone stressors and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12:111–126. doi: 10.1023/A:1024750417154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yehuda R, Southwick SM, Giller EL. Exposure to atrocities and severity of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam combat veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(3):333–336. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bailey RH, Clark C, Dunbar D, Goolrick W, Walker BS, Wiencek H. New York, New York: Prentice Hall Press; 1990. Brother Against Brother. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dean ET. “We Will All Be Lost and Destroyed”: Post-traumatic stress disorder and the Civil War”. Civil War History. 1991;38(2):138–153. doi: 10.1353/cwh.1991.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fogel RW. Center for Population Economics, University of Chicago Graduate School of Business, and Department of Economics; Brigham Young University: 2000. Public use tape on the aging of veterans of the Union Army: Military, pension, and medical records, 1860–1940, version M-5. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deutrich M. Public Affairs Press; 1962. Struggle for supremacy: The career of General Fred C. Ainsworth. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fogel RW. Center for Population Economics, University of Chicago Graduate School of Business, and Department of Economics, Brigham Young University; 2001. Public use tape on the aging of veterans of the Union Army: Surgeon’s certificates, 1862–1940, version S-1 standardized. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson SE. Unpublished Manuscript. Center for Population Economics, University of Chicago.; 1993. Notes on the rejection sample. [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization. 5th edition. Los Angeles, CA: Practice Management Information Corporation; 1999. International classification of diseases 9th revision: Clinical modification. [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis CS. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. Statistical methods for the analysis of repeated measurements. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. Logistic regression: A self-learning test. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa DL. Height, weight, wartime stress, and older age mortality: evidence from the Union Army records. Explorations in Economic History. 1993;30:424–449. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rutkow IM. New York: Random House; 2005. Bleeding Blue and Gray: Civil War surgery and the evolution of American medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McEwen BS. The neurobiology and neuroendocrinology of stress: implications for post-traumatic stress disorder from a basic science perspective. Psychiatric Clin of North Am. 2002;25(2):469–494. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(01)00009-0. Special Issue: Recent advances in the study of biological alterations in posttraumatic stress disorder. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henry JP, Wang S. Effects of early stress on adult affiliative behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:863–875. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavlides C, Nivon LG, McEwen BS. Effects of chronic stress on hippocampal long-term potentiation. Hippocampus. 2002;21(2):245–257. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krantz DS, Sheps D, Carney RM, Natelson BH. Effects of mental stress in patients with coronary artery disease: evidence and clinical implications. JAMA. 2000;283:1800–1802. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Handbook of stress, medicine and health. CRC Press; 1996. Stress, endocrine manifestations, and diseases; pp. 61–83. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psych Bulletin. 2004;130:601–630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wooley CF. The History of Medicine in Context. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate; 2002. The irritable heart of soldiers and the origins of Anglo-American cardiology: The U.S. Civil War (1861) to World War I (1918) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang HK, Hyams KC. Mental health care needs among recent war veterans. NEJM. 2005;352:1289. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]