Abstract

Objectives. We examined whether self-reported racial discrimination was associated with mental health status and whether this association varied with race/ethnicity or immigration status.

Methods. We performed secondary analysis of a community intervention conducted in 2002 and 2003 for the New Hampshire Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health 2010 Initiative, surveying African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos. We assessed mental health status with the Mental Component Summary (MCS12) of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12, and measured discrimination with questions related to respondents’ ability to achieve goals, discomfort/anger at treatment by others, and access to quality health care.

Results. Self-reported discrimination was associated with a lower MCS12 score. Additionally, the strength of the association between self-reported health care discrimination and lower MCS12 score was strongest for African descendants, then Mexican Americans, then other Latinos. These patterns may be explained by differences in how long a respondent has lived in the United States. Furthermore, the association of health care discrimination with lower MCS12 was weaker for recent immigrants.

Conclusions. Discrimination may be an important predictor of poor mental health status among Black and Latino immigrants. Previous findings of decreasing mental health status as immigrants acculturate might partly be related to experiences with racial discrimination.

Recent reports argue that racial discrimination is not only a critical civil rights issue, but also an important topic of scientific inquiry.1–3 Self-reported discrimination, the recounting of one’s experiences with being unfairly treated because of one’s race/ethnicity, is associated with poor mental health status for Blacks,4–8 Latinos,9–11 Asian/Pacific Islanders,12–14 American Indians,15 and even for the general population.16 The mechanisms underlying this relation include stress, trauma, internalized oppression, health care barriers, and other socioeconomic and structural disadvantages.6,17–20

Although nearly all minority groups in the United States share the experience of facing racial/ethnic discrimination, there are clear historical and contextual differences between groups.21,22 One difference is the proportion of immigrants within each group. For example, few Blacks (6.1%) are immigrants compared with Latinos (40.2%).23 Although certainly not the only factor, being an immigrant may influence health and discrimination in important ways.

Immigrants of any race/ethnicity in the United States are often healthier than nonimmigrants.24 Generally, foreign-born Americans have lower rates of mental disorders than those born in the United States, and increasing time in the United States is associated with increasing rates of mental health problems among immigrants.25–33 Recent Mexican immigrants have psychiatric disorder rates lower than those of the general US population. However, US-born Mexican Americans have rates similar to those of the US population.34,35

Minority immigrants may experience discrimination differently than do their US-born counterparts. Immigrants report more discrimination with increasing time in the United States,11,36 perhaps because of the “acquisition of involuntary minority status as [immigrants] come to understand their relative position in the larger sociocultural environment of the US.”37(p454) That is, increasing length of residency may lead to more experiences with and recognition of discrimination.38 New Black immigrants may be treated better than their US-born peers, although these advantages may erode over time.39,40 Further, acculturation may moderate the association between discrimination and mental health for immigrants.11,12 In effect, new immigrants may be able to protect against the mental health effects of discrimination by perceiving their negative experiences as stemming from unfamiliarity with US culture, rather than their race/ethnicity.

Our study focused on Latinos, emphasizing Mexican Americans, and Blacks. Latinos are the fastest-growing segment of the US population, and Mexican Americans make up 59% of all US Latinos.41 Despite a growing literature on the effects of discrimination on health, only a few studies have examined immigrant Latinos and Blacks.42

On the basis of previous work, our first hypothesis was that self-reported discrimination would be negatively associated with mental health status. Our second hypothesis was that this association would be stronger for Blacks than for Latinos. We posed this hypothesis for 2 reasons. First, discrimination may be qualitatively different for Blacks than for other groups. For example, whereas Blacks tend to live segregated from Whites regardless of their socioeconomic status, as Latinos and Asians move up in socioeconomic status they are less likely to live segregated from Whites.43,44 Second, immigrants of any race/ethnicity may have a shorter “exposure period” to discrimination than their US-born counterparts simply by virtue of having spent less time in the United States. Hence, the association between discrimination and health might be weaker for Latinos than for Blacks because Latinos are more likely to be immigrants and have less opportunity to experience and accumulate experiences of discrimination.

This leads to our third hypothesis. If time in the United States reflects a longer period of exposure to discrimination, then the association between discrimination and mental health should be weaker for newer immigrants than for immigrants with a longer period of US residency, regardless of ethnicity.

To address health disparities, it is important to have full knowledge about the experience of racial/ethnic groups across the nation.45 However, most studies have focused either on national samples or on areas of high minority concentration;42 few have examined areas where minorities are less well represented. To address this gap, we examined a sample from New Hampshire, where 95.1% of the population in 2000 was non-Hispanic White, compared with 69.1% of the US population.46

METHODS

Sample

Data were from the New Hampshire Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (NH REACH) 2010 Initiative. Sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NH REACH 2010 was designed to implement culturally effective programs for addressing health disparities in diabetes and hypertension within the Black and Latino populations. We analyzed the 2002–2003 baseline survey data from this larger initiative.

New Hampshire is a challenging place to research racial/ethnic groups. In 2000, the state’s racial composition was 95.1% White, 0.7% Black, 1.1% multiple-race, and 3.1% Asian American, Pacific Islander, or American Indian.46 Latinos of any race constituted 1.7%.46 Over half of all Blacks and Latinos in the state lived in Hillsborough County, and over a quarter of those were concentrated in the cities of Manchester and Nashua. Despite this concentration, Blacks and Latinos constituted only 1.2% and 3.2%, respectively, of the 398 574 residents of Hillsborough County. In Hillsborough, 26% of Blacks and 33% of Latinos were foreign-born.47

Respondents were recruited through snowball sampling (the recruitment of participants from the networks of extant participants) for 2 reasons: (1) a random sample would not efficiently find racial/ethnic minority respondents in this area, and (2) trust from word-of-mouth referrals helped us recruit some participants who may have otherwise hesitated to participate. Trained peer educators administered the face-to-face surveys in English or Spanish. Additional details can be found at http://www.nhhealthequity.org.

Measures

Because discrimination is a stressor that may have multiple effects on health, focusing on specific disorders may underestimate the influence of discrimination on well-being.13,19,42 We examined a measure of overall psychological well-being, the Mental Component Summary (MCS12) subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12, a shortened version of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36. The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12 is designed to be a valid, reliable, cost-effective measure of health-related quality of life in both clinical and population-based studies.48,49 Questions focus on vitality, social functioning, role functioning, mental health, general health, physical functioning, and bodily pain. Higher scores indicate better mental health. Low MCS12 scores have been associated with clinical depression and more general measures of diminished mental health status.50,51 The scale has been used among disadvantaged and culturally diverse populations.52,53

We employed 3 indicators of discrimination. The term “discrimination” signifies the 3 measures collectively, and individual measures are referenced by their respective names.

For the first measure, goals discrimination, we asked, “Do you feel that racial discrimination diminishes your ability to achieve your goals fully?” Responses were “yes” or “no.” For the second item, discomfort/anger, we asked, “How often do you feel discomfort or anger by the way others treat you in your everyday life because of your race?” The Spanish version added the concept of ethnicity as a source of discrimination: “¿Cuántas veces se ha sentido incómodo o enojado por la forma en que es tratado en su vida diaría por su raza o etnicidad?” (“How often do you feel discomfort or anger by the way others treat you in your everyday life because of your race or ethnicity?”). Response categories ranged from “constantly” to “never” on a 6-point scale, but were collapsed to “never” versus all others to more parsimoniously test the interaction analyses. For the third measure, health care discrimination, we asked, “Do you feel that you have been receiving less than the best health care because of your race?” Responses were “none of the time,” “some of the time,” or “often.” We combined the latter 2 because few participants (n = 27) answered “often.”

Supplemental analyses (not shown) found that an index of all 3 measures predicted lower MCS12 scores. The association between global measures of discrimination and mental health has been documented, and interest exists in understanding specific types of discrimination.16,19,42 Accordingly, we report on the individual items rather than the summary scale, recognizing the limits of single-item indicators.54

“Immigrant” denotes whether the person was foreign-born. “Years of residency” indicates the length of time immigrants have lived in the United States. The NH REACH 2010 staff adopted the phrase “African descendant” to be inclusive of persons with ancestral roots in Africa, including African Americans and immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean.

Respondents were first asked whether they were Hispanic/Latino, then asked their race. One participant of both African and Latino descent chose to be classified as “African Descendant” by opting into that arm of the intervention part of the study. There were 202 Mexican Americans. Other Hispanics/Latinos (56 Puerto Ricans, 98 Dominicans, 120 South Americans) were collapsed into a category called “Other Latino” to achieve a more stable sample size. US-born Mexican Americans and other Latinos were dropped from the analyses because of small numbers (n = 14). African descendants were not disaggregated because of small subgroups (78 US-born, 26 Haitians, 20 Sudanese, 11 Jamaicans, 93 other).

Our focus was on African descendants and Mexican Americans. Other Latinos were too heterogeneous to make precise inferences, but were included to see if Mexican Americans were meaningfully distinct from the more general category of “Latino.” Other covariates included gender, income, education, medical insurance (present or not), current employment, and age.

Analysis

After data preparation, analyses began with simple bivariates between study measures. We then used multiple linear regression to adjust for covariates. Predictor variables were mean centered. We tested the main effects of each measure of discrimination independently to examine the first hypothesis—that self-reported discrimination would be negatively associated with mental health status. To evaluate the second hypothesis—that discrimination would be stronger for African descendants than for the other groups—we tested the interaction between ethnicity and discrimination. Simple slopes and graphs were used to clarify significant interactions.55

For the test of the third hypothesis—that length of residency would moderate the association between discrimination and MCS12 score—we omitted US-born African descendants (n = 78) because length of residency is collinear with age (r = 0.92) for nonimmigrants. We examined whether length of residency explained the main effects of discrimination and accounted for any significant interactions. We then tested interactions between each measure of discrimination and length of residency.

Because of the snowball sampling method, several respondents (41% of African descendants, 65% of Mexican Americans, and 58% of other Latinos) lived in the same household as another respondent. To correct for nonindependence of observations within households, we used robust cluster variance estimators to produce standard errors using Stata version 9.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Tex).

RESULTS

Table 1 ▶ displays characteristics of the study sample, stratified by ethnicity. There were no differences in mental health according to ethnicity. Compared with the other groups, African descendants were more likely to be male and had higher levels of education, rates of employment, income, and rates of being insured. Mexican Americans reported the shortest period of residency in the United States, and the lowest rates of insurance and levels of education. Compared to the other 2 groups, other Latinos were more likely to be female and older, and generally scored in-between the other groups in socioeconomic characteristics. All of the Mexican Americans and other Latinos and 58.9% of all African descendants were immigrants. Compared with the population of Black and Latino residents in Hillsborough County, NH REACH respondents were younger, more likely to be immigrants, and of lower socioeconomic position (county data not shown).

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Characteristics of NH REACH 2010 Sample, by Ethnicity

| African Descendant (n = 190), % | Mexican American (n = 202), % | Other Latino (n = 274), % | Total Sample (N = 666), % | |

| MCS12 score, mean ±SD | 48.99 ±9.92 | 48.61 ±8.78 | 47.73 ±10.70 | 48.36 ±9.93 |

| Years residency in United States, mean ±SD*** | 20.67 ±18.16 | 6.05 ±6.13 | 9.88 ±9.87 | 11.80 ±13.38 |

| Years of age, mean ±SD*** | 36.68 ±12.55 | 31.73 ±10.56 | 44.10 ±14.26 | 38.23 ±13.77 |

| Male* | 38.95 | 30.20 | 28.47 | 31.98 |

| Insured*** | 63.68 | 24.75 | 44.53 | 43.99 |

| Immigrant*** | 58.90 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 88.20 |

| Educational level | ||||

| < 9th grade*** | 1.58 | 50.99 | 34.31 | 30.03 |

| Some high school | 14.21 | 28.22 | 18.25 | 20.12 |

| High school graduate/general equivalency diploma | 28.95 | 13.37 | 19.71 | 20.42 |

| Any college | 55.26 | 7.43 | 27.74 | 29.43 |

| Employed* | 63.16 | 51.98 | 51.82 | 55.11 |

| Income, $ | ||||

| < 10 000*** | 22.63 | 23.76 | 23.36 | 23.27 |

| 10 000–24 999 | 27.89 | 40.10 | 38.32 | 35.89 |

| 25 000–49 999 | 25.26 | 13.86 | 14.23 | 17.27 |

| ≥ 50 000 | 14.74 | 4.46 | 7.30 | 8.56 |

| Data missing | 9.47 | 17.82 | 16.79 | 15.02 |

| Reported discrimination | ||||

| Goals*** | 32.43 | 63.27 | 54.31 | 50.77 |

| Discomfort/anger*** | 63.19 | 49.25 | 40.59 | 49.54 |

| Health care*** | 28.38 | 28.81 | 15.47 | 22.88 |

Note. NH REACH = New Hampshire Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health; MCS12 = Mental Component Summary subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001, for tests of significance between ethnic groups.

Reports of health care discrimination were similar between African descendants and Mexican Americans, but lower among other Latinos. Reports of goals discrimination were highest among Mexican Americans, then other Latinos. Reports of discomfort/anger discrimination were highest for African descendants, followed by Mexican Americans.

Table 2 ▶ shows mean MCS12 scores according to ethnicity and reports of discrimination. All 3 measures of discrimination were associated with lower MCS12 scores, but the differences were strongest for African descendants, then Mexican Americans and weakest among other Latinos. For example, the difference in MCS12 scores between those reporting goals discrimination and those not reporting was −4.25, −2.77, and −1.56 for African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos, respectively.

TABLE 2—

Mean MCS12 Score (±SD) and Self-Reported Discrimination, by Ethnicity (Unadjusted)

| African Descendant | Mexican American | Other Latino | Total Sample | |

| Goals discrimination | ||||

| Not reported | 50.20 ±8.88 | 50.32 ±7.97 | 48.89 ±10.53 | 49.72 ±9.36 |

| Reported | 45.95 ±11.35 | 47.55 ±8.98 | 47.33 ±10.44 | 47.16 ±10.08 |

| (Reported) – (Not reported) | −4.25*** ±1.53 | −2.77* ±1.30 | −1.56 ±1.29 | −2.56 ±0.78 |

| Discomfort/anger discrimination | ||||

| Not reported | 52.21 ±7.83 | 50.24 ±8.40 | 48.35 ±10.99 | 49.72 ±9.75 |

| Reported | 46.86 ±10.63 | 6.88 ±8.89 | 46.85 ±9.99 | 46.86 ±9.88 |

| (Reported) – (Not reported) | −5.35*** ±1.50 | −3.36** ±1.23 | −1.50 ±1.31 | −2.86 ±0.77 |

| Health care discrimination | ||||

| Not reported | 50.04 ±9.09 | 49.75 ±7.88 | 48.03 ±10.42 | 49.23 ±9.52 |

| Reported | 43.53 ±10.96 | 46.60 ±10.58 | 45.69 ±12.27 | 45.35 ±11.21 |

| (Reported) – (Not reported) | −6.51*** ±1.76 | −3.15* ±1.46 | −2.34 ±1.87 | −3.88 ±0.99 |

Note. MCS12 = Mental Component Summary subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001, for the difference in mean MSC12 score between those reporting and not reporting discrimination.

Table 3 ▶ shows the results of multivariate analyses that included discrimination, ethnicity, age, income, insurance, employment, education, gender, and nativity. Ethnicity and immigration were not significant predictors of MCS12 score (Model 1). Consistent with the first hypothesis, the main effects of all 3 measures of discrimination were associated with lower MCS12 scores (Models 2–4).

TABLE 3—

Relationship Between Self-Reported Discrimination and MCS12 Score

| Full Sample (N = 666), b (SE) | Immigrant Sample (N = 579), b (SE) | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| African Descendant | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Mexican American | 2.370 (1.369) | 3.169 (1.153) | 2.452 (1.302) | 2.551 (1.604) | 1.438 (1.524) | 1.858 (1.498) | 0.987 (1.499) | 2.020 (1.670) |

| Other Latino | 0.225 (0.926) | 1.261 (0.834) | 0.447 (0.909) | −0.237 (1.138) | −0.426 (1.172) | 0.205 (1.117) | −0.777 (1.111) | −0.503 (1.295) |

| Immigrant | 0.635 (1.053) | 0.952 (1.229) | 1.218 ( 1.030) | 0.285 (1.267) | −0.062 (0.051) | −0.080 (0.056) | −0.075 (0.052) | −0.050 (0.057) |

| Goals discrimination | … | −2.189***(0.665) | … | … | … | −1.869* (0.743) | … | … |

| Discomfort/anger discrimination | … | … | −3.575*** (0.725) | … | … | … | −3.224*** (0.765) | … |

| Health care discrimination | … | … | … | −4.379** (1.599) | … | … | … | −3.865* (1.557) |

| Constant | 44.922*** (1.425) | 45.329*** (1.406) | 46.371*** (1.358) | 46.328*** (1.523) | 45.751*** (1.665 | 46.206*** (1.708) | 47.523*** (1.576) | 47.037*** (1.835) |

Note. Models were adjusted for age, gender, insurance, income, and employment.

* P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

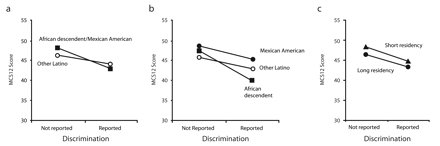

Our second hypothesis, that the slope of discrimination would be steeper for African descendants than for Mexican Americans and other Latinos, was partially supported. The interaction between discomfort/anger discrimination and other Latinos was significant. The slope of discrimination for Mexican Americans and African descendants (b = −5.29) was steeper than that for other Latinos (b = −2.01) (Figure 1a ▶). There was also a significant interaction between health care discrimination and ethnicity (Figure 1b ▶). The slope of discrimination was steepest for African descendants (b = −7.94), followed by Mexican Americans (b = −4.85), then other Latinos (b = −2.98). The interaction between goals discrimination and ethnicity was not statistically significant, but was in a similar direction as the other models. Nativity neither predicted MCS12 score nor changed the significance of the interaction.

FIGURE 1—

Associations between self-reported discrimination and MCS12 score for discomfort/anger discrimination, by ethnicity (a); health care discrimination, by ethnicity (b); and health care discrimination, by length of residency in the United States (c).

Note. MCS12 = Mental Component Summary subscale from the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 12. Age, gender, nativity, income, education, insurance, and employment were controlled. “Short residency” and “long residency” refer to 1 standard deviation below and above the mean, respectively, in terms of years in the United States. Figures 1a and 1b include both immigrants and US-born respondents; Figure 1c includes only immigrants.

We replicated these analyses with the immigrant subset and included length of residency. The main effects of ethnicity and length of residency were not associated with MCS12 score (Table 3 ▶, Model 5). However, the main effects of goals, discomfort/anger, and health care discrimination were still negatively associated with MCS12 score (Models 6–8).

When length of residency was excluded from the model, the interaction between health care discrimination and ethnicity remained significant (not shown). However, the interactions became nonsignificant when length of residency was included. Thus, length of residency appeared to explain the differences by ethnicity in the association between discrimination and health.

We found partial support for the hypothesis that length of residency moderated discrimination. There was a significant interaction between health care discrimination and length of residency (Figure 1c ▶). Those who had immigrated less recently had lower MCS12 scores than more recent immigrants regardless of the level of discrimination. However, the association between health care discrimination and MCS12 score was steeper for less recent than more recent immigrants (b = −2.83 vs. b = −2.31). That is, the relation between health care discrimination and mental health was stronger for immigrants with longer period of residency than for more recent arrivals. Length of residency did not significantly moderate the association between goals or discomfort/anger discrimination and MCS12 score, but the coefficients were of the same direction (not shown). There were no significant 3-way interactions between ethnicity, length of residency, and discrimination.

DISCUSSION

The data suggest 3 main findings. First, reports of discrimination were associated with lower ratings of mental health after controlling for age, gender, education, employment, income, insurance, nativity, and ethnicity. Second, the association between discrimination and mental health appeared stronger for African descendants than for Mexican Americans and other Latinos, but this may be explained by immigration factors. Third, the association between discrimination and mental health may be stronger for immigrants who have lived in the United States longer than for more recent arrivals.

Our study joins others in demonstrating a negative association between reports of discrimination and mental health status.4,12,14,16,18,56–59 We differentiated between discrimination associated with goals, discomfort/anger, and health care. As expected, all 3 measures were associated with poor mental health status. Racial discrimination may impede people’s ability to achieve their goals. The incongruity between one’s goals and one’s ability to actualize them has been associated with increased psychological distress60–63 and might explain the association found here. Discomfort/anger discrimination was also associated with poor mental health status. This is not surprising, given that many studies report strong associations between discrimination and measures of distress and anxiety.6,11,16 Discrimination in health care was also associated with poor mental health. A growing number of studies document disparities in health services by minorities.1,64–67 Alegria25,28 suggested that racism and mistrust contribute to reduced use of mental health services among Latinos. Klassen and colleagues68 reported that distrust with medical services accumulated over a lifetime led Black clients to be less willing to try new services. Further, many ethnic groups use traditional healing practices.3,24,69 Immigrants may be more likely to use traditional healing in lieu of formal medical practices when confronted with racial discrimination.70 Thus, the mere perception that the health care system is unjust may make some individuals decline to seek formal treatment and may lead to widening disparities.19,71,72

Further, our study found partial support for moderation by race/ethnicity. In adjusted models, race/ethnicity did not moderate goals discrimination. However, it did moderate discomfort/anger and health care discrimination. The association between discomfort/anger discrimination and MCS12 scores was similar between African descendants and Mexican Americans, but weaker for other Latinos. This might be partially explained by unmeasured heterogeneity within the other Latinos. Given limitations of sample size, we did not disaggregate the other Latinos, but future research should do so. Taken together, the results suggest that despite different patterns of reporting, the strength of the association for goals and discomfort/anger discrimination is similar between Mexican Americans and African descendants.

Race/ethnicity also moderated health care discrimination. Health care discrimination was associated with poor mental health status for all groups, but the association was strongest for African descendants, then Mexican Americans, and then other Latinos. There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, the moderation could occur because discrimination might be especially pernicious for Blacks. This is consistent with observations that, whereas all groups experience discrimination, Blacks may face a type of discrimination that is qualitatively different from that of other groups. A second interpretation might be qualitative differences in the types of discrimination reported. For example, the African descendants in our study may have been apt to report only the more hazardous types of health care discrimination, which would be more likely to affect mental health status. Future research should examine such potential qualitative differences.

However, our analyses suggest a third interpretation. Discrimination may be more strongly associated with the mental health status of African descendants than with that of Mexican Americans and other Latinos because the latter 2 groups are more likely to be immigrants. Immigrants might experience less initial exposure to discrimination and may have some resources that can temporarily buffer the effects of discrimination.12,73–76 These group differences may erode as immigrants encounter more discrimination and the deleterious effects of discrimination accumulate over time. This would be the immigrant variant of Geronimus’s “weathering hypothesis.”31,77,78 That is, increasing length of residency might “weather away” protective buffers and simultaneously allow disadvantage to accrue.

Consistent with these arguments, interactions between discrimination and race/ethnicity were no longer significant when we included length of residency in the models. Additionally, the negative association between health care and mental health status was stronger for immigrants with a longer period of residency than for more recent arrivals.

Period of residency in the United States is used more commonly as a proxy for acculturation than as a proxy for exposure to discrimination. The unidimensional view of acculturation suggests that “immigrants” adopt the cultures of the host country.79–82 Although we cannot rule out this interpretation because we did not directly measure culture, one might expect the sign of the interaction to be reversed. That is, as immigrants become more like host members, they may encounter less discrimination and the impact of discrimination may be attenuated. However, we did not find this to be the case, suggesting that length of residency may better represent the embodiment of discrimination than cultural adoption.

One other explanation cannot be ruled out. We found an interaction between length of residency in the United States and health care discrimination, but not between discomfort/anger or goals discrimination. It might be that our finding was because of chance. However, the other interactions were in a similar direction, suggesting that the null findings might have been because of low power. Additional studies are needed to confirm or disprove these explanations.

Other caveats should be mentioned. First, we cannot establish causal relationships because this study was cross-sectional. The few longitudinal studies that have been conducted do suggest that the causal direction is from discrimination to illness.57,83 However, we need more longitudinal studies to better understand these issues.

Second, participants were nonrandomly selected, leaving open questions as to generalizability and potential selection biases. By its very nature, snowball sampling draws respondents who are interrelated. Our sample overrepresented immigrants, and respondents were of lower socioeconomic status and age than Latinos and Blacks in Hillsborough County. We were unable, because of sample constraints, to examine US-born Latinos. These limitations were weighed against the desire to recruit participants into an intervention in a county where Latinos and Blacks represented 3.2% and 1.3% of the population, respectively. Within this community, the snowball technique allowed for more efficient identification of members of the target population. Additionally, because respondents were referred to the study by a known source, this method may have allowed for the inclusion of some participants who may not have otherwise participated in the study. Nonetheless, our findings must be interpreted with these limitations in mind.

Third, we were limited in the measures available in our secondary analysis. Discrimination was self-reported, leaving open potential response biases.54,84 Our measures consisted of reports that may not have represented objective experiences. However, perceptions have importance in their own right as they may represent how people see their position in society and may indicate the stressors present in their lives.19,42 Each domain of discrimination consisted of a single item, and future work should examine these domains with full scales.54 Single-item measures of discrimination tend to underestimate the prevalence of discrimination and are less reliable than full scales.13,54 We measured only 3 domains, leaving unexplored other types of discrimination, including interpersonal discrimination and implicit forms of discrimination (e.g., stereotype threat). There are no gold standard measures of discrimination, although several promising scales do exist and should be used in future research.19,54,57,64,85,86

With these caveats in mind, our findings show that racial/ethnic discrimination is associated with poor mental health status. At first glance, the association between health care discrimination and mental health may be stronger for African descendants than for Mexican Americans and other Latinos, but this relation might be explained by differences in immigration factors. The finding that the relation between health care discrimination and mental health is stronger for immigrants who have lived in the United States longer is troubling, as it implies that discrimination may erode not only mental health, but also the resources available to racial/ethnic minorities to buffer against discrimination. These findings suggest that policies designed to reduce discrimination are not only a moral imperative, but also a key tool in protecting public health.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement U50/CCU122162). The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC.

We thank Jorge Delva and Mellisa Valerio for helpful comments on drafts of this manuscript. We also thank Chris Smith and Jazmin Miranda-Smith for their gracious support and feedback on this study.

Human Participant Protection This protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Dartmouth–Hitchcock Medical Center.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors G. C. Gee led the writing and conceptualization of this analysis. A. Ryan participated in the analysis and writing. D. J. Laflamme participated in the writing and data preparation. J. Holt directed the NH REACH 2010 project and contributed to the preparation of this study.

References

- 1.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed]

- 2.Blank RM, Dabady M, Citro CF, eds. Measuring Racial Discrimination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

- 3.Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [PubMed]

- 4.Williams DR. Race, stress, and mental health: findings from the Commonwealth Minority Health Survey. In: Hogue CJR, Hargraves MA, Collins KS, eds. Minority Health in America: Findings and Policy Implications from the Commonwealth Fund Minority Health Survey. Baltimore, Md: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000:209–243.

- 5.Fischer AR, Shaw CM. African Americans’ mental health and perceptions of racist discrimination: the moderating effects of racial socialization experiences and self-esteem. J Couns Psychol. 1999;46:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DR, Willams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: the African American experience. Ethn Health. 2000;5:243–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz A, Williams D, Israel B, et al. Unfair treatment, neighborhood effects, and mental health in the Detroit metropolitan area. J Health Soc Behav. 2000; 41:314–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caughy MO, O’Campo PJ, Muntaner C. Experiences of racism among African American parents and the mental health of their preschool-aged children. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2118–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuber J, Galea S, Ahern J, Blaney S, Fuller C. The association between multiple domains of discrimination and self-assessed health: a multilevel analysis of latinos and blacks in four low-income New York City neighborhoods. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(6 pt 2): 1735–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finch B, Hummer RA, Kolody B, Vega WA. The role of discrimination and acculturative stress in Mexican-origin adults’ physical health. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2001;23:399–429. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93: 232–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional racial discrimination and health status. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:615–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhui K, Stansfeld S, McKenzie K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J, Weich S. Racial/ethnic discrimination and common mental disorders among workers: findings from the EMPIRIC Study of Ethnic Minority Groups in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health. 2005;95: 496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitbeck LB, McMorris BJ, Hoyt DR, Stubben JD, Lafromboise T. Perceived discrimination, traditional practices, and depressive symptoms among American Indians in the Upper Midwest. J Health Soc Behav. 2002; 43:400–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretical framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000; 90:1212–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger N. Embodying inequality: a review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int J Health Serv. 1999;29: 295–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a bio-psychosocial model. Am Psychologist. 1999;54: 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feagin JR. Racist America: Roots, Current Realities, and Future Reparations. New York, NY: Routledge; 2001.

- 22.Zhou M. Contemporary immigration and dynamics of race and ethnicity. In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, eds. America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences. Vol 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001:200–242.

- 23.Malone N, Baluja KF, Costanzo JM, Davis CJ. The Foreign-Born Population: 2000. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; December 2003. Census 2000 brief C2KBR-34.

- 24.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Anderson K. Immigration and lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1226–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino Whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1547–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takeuchi DT, Chun CA, Gong F, Shen H. Cultural expressions of distress. Health. 2002;6:221–236. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vega W, Kolody B, Valle R, Hough R. Depressive symptoms and their correlates among immigrant Mexican women in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 1986; 22:645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alegria M, Perez DJ, Williams S. The role of public policies in reducing mental health status disparities for people of color. Health Aff. 2003;22:51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Escobar JL, Hoyos NC, Gara MA. Immigration and mental health: Mexican Americans in the United States. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2000;8:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gee GC, Payne-Sturges DC. Environmental health disparities: a framework integrating psychosocial and environmental concepts. Environ Health Perspect. 2004; 112:1645–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geronimus AT. To mitigate, resist, or undo: addressing structural influences on the health of urban populations. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:867–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geronimus AT, Thompson JP. To denigrate, ignore, or disrupt: the health impact of policy-induced breakdown of urban African American communities of support. Du Bois Rev. 2004;1:247–279. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderte E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga H. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:771–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goto SG, Gee GC, Takeuchi DT. Strangers still? The experience of discrimination among Chinese Americans. J Community Psychol. 2002;30:211–224. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: longitudinal relations. J Community Psychol. 2000;28:443–458. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Portes A, Parker RN, Cobas JA. Assimilation or consciousness: perceptions of US society among recent Latin American immigrants to the United States. Soc Forces. 1980;59:200–224. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waters MC. Black Identities: West Indian Immigrant Dreams and American Realities. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 2000.

- 40.Read JG, Emerson MO. Racial context, black immigration and the US black/white health disparity. Soc Forces. 2005;84:181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2005.

- 42.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Massey DS, Denton NA. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1993.

- 44.Massey DS. Residential segregation and neighborhood conditions in US metropolitan areas. In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, eds. America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences. Vol 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001:391–434.

- 45.Healthy People 2010: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1991. DHHS publication PHS 91-50212.

- 46.US Census Bureau. The population profile of the United States: 2000 (Internet release). Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/profile2000.html. Accessed June 27, 2006.

- 47.Census 2000 Summary File 3 (SF 3). Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census.

- 48.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to Score the SF-12 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales. 3rd ed. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric; 1998.

- 49.Burdine JN, Felix MR, Abel AL, Wiltraut CJ, Musselman YJ. The SF-12 as a population health measure: an exploratory examination of potential for application. Health Serv Res. 2000;35:855–904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harpole LH, Williams JW Jr, Olsen MK, et al. Improving depression outcomes in older adults with co-morbid medical illness. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27: 4–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franks P, Lubetkin EI, Gold MR, Tancredi DJ, Jia H. Mapping the SF-12 to the EuroQol EQ-5D Index in a national US sample. Med Decis Making. 2004;24: 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Larson CO. Use of the SF-12 instrument for measuring the health of homeless persons. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:733–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franks P, Lubetkin EI, Gold MR, Tancredi DJ. Mapping the SF-12 to preference-based instruments: convergent validity in a low-income, minority population. Med Care. 2003;41:1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1576–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1991.

- 56.Jackson JS, Brown TN, Williams DR, Torres M, Sellers SL, Brown K. Racism and the physical and mental health status of African Americans: a thirteen year national panel study. Ethn Dis. 1996;6:132–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. Am J Health Psychol. 1997;2:335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ortega AN, Rosenheck R, Alegria M, Desai RA. Acculturation and the lifetime risk of psychiatric and substance use disorders among Hispanics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty, and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: findings from 3 US cities. Am J Public Health. 2001;91: 927–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dressler WW. Social consistency and psychological distress. J Health Soc Behav. 1988;29:79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.James SA. John Henryism and the health of African-Americans. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1994;18:163–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neighbors HW, Jackson JS, Broman C, Thompson E. Racism and the mental health of African Americans: the role of self and system blame. Ethn Dis. 1996;6: 167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sellers R, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:1079–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(suppl 1):146–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wade JC. Institutional racism: an analysis of the mental health system. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63: 536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Diala CC, Muntaner C, Walrath C, Nickerson K, LaVeist T, Leaf P. Racial/ethnic differences in attitudes toward seeking professional mental health services. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:805–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Catalano R. Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156: 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klassen AC, Hall AG, Saksvig B, Curbow B, Klassen DK. Relationship between patients’ perceptions of disadvantage and discrimination and listing for kidney transplantation. Am J Public Health. 2002;92: 811–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vega WA, Rumbaut RG. Ethnic minorities and mental health. Annu Rev Sociol. 1991;17:351–383. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spencer MS, Chen J. Effect of discrimination on mental health service utilization among Chinese Americans. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:809–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams DR. Racial variations in adult health status: patterns, paradoxes, and prospects. In: Smelser N, Wilson WJ, Mitchell F, eds. America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences. Vol 2. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001:371–410.

- 72.LaVeist TA, Rolley NC, Diala C. Prevalence and patterns of discrimination among US health care consumers. Int J Health Serv. 2003;33:331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodriguez MC, Morrobel D. A review of Latino youth development research and a call for an asset orientation. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2004;26:107–127. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: a study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gee GC, Chen J, Spencer MS, et al. Social support as a buffer for perceived unfair treatment among Filipino Americans: differences between San Francisco and Honolulu. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:677–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Denner J, Kirby D, Coyle K, Brindis C. The protective role of social capital and cultural norms in Latino communities: a study of adolescent births. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2001;23:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geronimus AT. Black/White differences in the relationship of maternal age to birthweight: a population-based test of the weathering hypothesis. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Geronimus AT. Understanding and eliminating racial inequalities in women’s health in the United States: the role of the weathering conceptual framework. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2001;56:133–136, 149–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arcia E, Skinner M, Bailey D, Correa V. Models of acculturation and health behaviors among Latino immigrants to the US. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Escobar JI, Vega WA. Mental health and immigration’s AAAs: where are we and where do we go from here? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hunt LM, Schneider S, Comer B. Should “acculturation” be a variable in health research? A critical review of research on US Hispanics. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:973–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burnam MA, Hough RL, Karno M, Escobar JI, Telles CA. Acculturation and lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28:89–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pavalko EK, Mossakowski KN, Hamilton VJ. Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between work discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44:18–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: conceptual and measurement problems. Am J Public Health. 2003;93: 262–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jones CP, Ogbara T, Braveman P. Disparities in infectious disease among women in developed countries. Emerg Infect Dis [online serial]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol10no11/04-0624_08.htm. Accessed June 27, 2006.

- 86.Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: a measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. J Black Psychol. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]