Abstract

We have generated transgenic mice containing hybrid llama/human antibody loci that contain two llama variable regions and the human D, J, and Cμ and/or Cγ constant regions. Such loci rearrange productively and rescue B cell development efficiently without LC rearrangement. Heavy-chain-only antibodies (HCAb) are expressed at high levels, provided that the CH1 domain is deleted from the constant regions. HCAb production does not require an IgM stage for effective pre-B cell signaling. Antigen-specific heavy-chain-only IgM or IgGs are produced upon immunization. The IgG is dimeric, whereas IgM is multimeric. The chimeric HCAb loci are subject to allelic exclusion, but several copies of the transgenic locus can be rearranged and expressed successfully on the same allele in the same cell. Such cells are not subject to negative selection. The mice produce a full antibody repertoire and provide a previously undescribed avenue to produce specific human HCAb in the future.

Keywords: immunoglobulin rearrangement, transgenic

Conventional antibodies contain two heavy and light chains (LC) coded for by heavy and LC loci. B cell development and antibody production starts in the bone marrow (BM) by heavy chain (HC) VDJ recombination and expression of IgM associated with a surrogate LC on the cell surface. In a second round of recombination, one of the LC rearranges in pre-B cells. If successful, the B cells undergo selection, affinity maturation, and switching to different HC constant regions to result in B cells, which express tetrameric antibodies of different isotypes (IgA, IgG, and IgE). Normally absence of HC or LC expression leads to arrest of B cell development. However, some species produce HC-only antibodies (HCAb) as part of their normal B cell development and repertoire. The best-known HCAb (i.e., no LC) are IgG2 and IgG3 in camelids (1). They undergo antigen-mediated selection and affinity maturation, and their variable domains are subject to somatic hypermutation (2, 3). HCAb are thought to recognize unusual epitopes, such as clefts on the antigen surface (4). The first domain of the constant region, CH1, is spliced out because of the loss of a consensus splice signal (5, 6). CH1 exon loss also has been described in other mammals, albeit associated with disease, e.g., in mouse myelomas (7) and human HC disease (HCD) (8–10).

Camelid HCAbs contain a complete VDJ region. Its size, stability, specificity, and solubility have generated considerable biotechnological interest. The antigen-binding site, a single-variable domain (VHH), resembles VH of conventional Abs. However, differences in FR2 and CDR3 prevent VHH to pair with a variable LC, whereas hydrophilic amino acids provide solubility (11). HCAb of the IgM class have not been found in camelids, suggesting that the IgM+ stage of HCAb formation is very transient and/or circumvented.

Murine NSO myeloma cells can express a rearranged camelid VHH-γ2a gene (12) and, recently, the same gene was expressed in transgenic mice (13). Here, we describe transgenic mice containing various nonrearranged chimeric HCAb loci and show they rearrange properly, result in allelic exclusion, efficiently rescue B cell development, and undergo class switch recombination and affinity maturation. They generate functional HCAbs after antigenic challenge, providing a previously undescribed way of producing human HCAb when the llama VHH regions are replaced with soluble human VH.

Results

The CH1 Splice Mutation Is Insufficient for Exon Skipping in the Human HC Locus.

It is not known whether the generation of HCAb (IgG2 and 3) in camelids needs an IgM+ stage. Hence, we made two hybrid chimeric loci, one locus (MGS) with human Cμ, Cδ, Cγ2, and Cγ3 constant regions and one with only Cγ2 and Cγ3 (GS; Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) in a μMT background (14). μMT animals do not produce surface IgM and have a block in B cell development at the pre-B cell stage. The Cγ regions first were mutagenized to contain the camelid CH1 splice mutation (5). GS was generated because of later reports showing that μMT mice produce some IgG, IgA, and IgE in the absence of membrane IgM (15–17), suggesting some B cells develop without IgM surface expression. Instead of mutating human VH domains to improve solubility (18, 19), two llama VHHs were introduced. Camelid VHH contain characteristic amino acids at positions 42, 49, 50, and 52 (20, 21). VHH1 contained these four, but VHH2 had a Q instead of an E at 49. The locus contained all of the human HC D and J regions and the locus control region (LCR) (Fig. 7). Surprisingly, the splice mutation gave incorrect CH1 exon skipping in mice and no chimeric Ig expression (Fig. 7).

Chimeric Loci Lacking a Human CH1 Region.

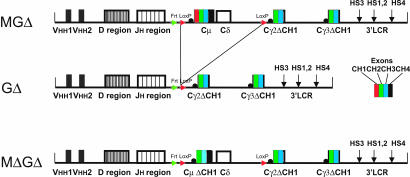

The CH1 splice problem was solved by generating three new constructs (Fig. 1), all containing Cγ2 and Cγ3 with CH1 deleted, one with Cμ and Cδ (MGΔ), one without Cμ and Cδ (GΔ), and one with CH1 deleted Cμ (MΔGΔ). Three MGΔ, six GΔ, and four MΔGΔ transgenic mouse lines with one to five copies were obtained in a μMT background. Mice with different copy numbers gave the same results.

Fig. 1.

The transgenic loci. Two llama VHH exons are linked to the human HC diversity (D) and joining (J) regions, followed by the Cμ, Cδ, Cγ2, and Cγ3 human genes and human HC Ig 3′ LCR. The different constant region exons are shown in different colors (see Middle Right Inset). CH1 (red) was deleted from Cγ2 and Cγ3 genes in constructs MGΔ and GΔ and also from Cμ in construct MΔGΔ. LoxP sites (in red) enable removal of Cμ and Cδ genes by cre recombination. The Frt site (in green) enables the generation of a single copy from a multicopy array by Flp recombination.

GΔ and MΔGΔ rescue B cell development.

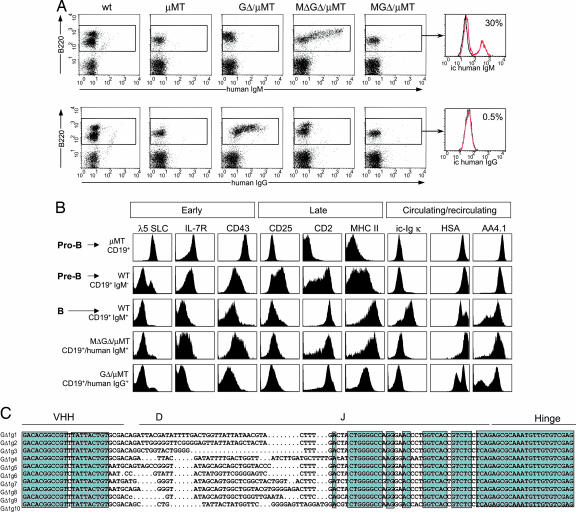

GΔ and MΔGΔ, but not MGΔ, rescued B cell development in a μMT background. The rescue of B220/CD19 cells was between 30% and 100% in different lymphoid compartments independent of copy number (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The MΔGΔ mice contain human IgM-producing cells in the BM absent in WT or μMT mice. Appropriately, they have not switched class because chimeric IgG is absent. The GΔ mice contain only chimeric IgG+ B cells. The MGΔ mice contain very few B cells expressing cell-surface chimeric Ig, but interestingly, 30% of the BM B220 cells express intracellular IgM, but not IgG (Fig. 2A). The MGΔ, but not the MΔGΔ and GΔ (data not shown), express mouse Ig LC (see Fig. 5G). Thus, the Cμ and Cγ genes are expressed, and absence of CH1 is crucial for surface-expressed HCAb.

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of B cells of wt, μMT, MGΔ/μMT, MΔGΔ/μMT, and GΔ/μMT mice in BM. (A) Lymphoid cells were gated on forward and side scatter. Surface expression of B220 and chimeric IgM or IgG is shown as dot plots. For MGΔ/μMT, the B220+ fraction was gated and analyzed for the expression of intracellular (ic) chimeric Ig μ and γ H chains, displayed as histogram overlays (red lines), with background stainings of B220+ cells from μMT mice (black lines) as controls. The % of positive cells is indicated. (B) MΔGΔ or GΔ transgenes rescue pre-BCR and BCR function. Shown are the expression profiles of the indicated markers in total CD19+ fractions from μMT mice (pro-B cells), in CD19+ surface IgM− fractions (pro-B/pre-B cells), and CD19+ surface IgM+ fractions (B cells) from WT, MΔ-GΔ μMT, and GΔ μMT mice. ic-Ig κ, intracellular Ig κ LC. Flow cytometric data are displayed as histograms representative of 3–8 animals examined in each group. (C) Sequence alignment of BM cDNA showing VDJ recombination. Sequences are from GΔ. Green shows sequence identity.

Table 1.

Percent of B220+/CD19+ cells in total population of nucleated cells

| Cell type | WT | GΔ (−5 copies) | GΔ (single copy) | MΔGΔ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 10.80 ± 2.09 | 5.94 ± 1.44 | 4.93 ± 1.79 | 6.06 ± 1.53 |

| Spleen | 41.80 ± 6.05 | 32.14 ± 9.46 | 28.70 ± 8.70 | 33.95 ± 3.24 |

| Blood | 43.72 ± 7.50 | 16.00 ± 5.68 | 16.01 ± 3.76 | 9.25 ± 3.24 |

| Peritoneum | 21.92 ± 9.90 | 22.85 ± 6.71* | 22.30 ± 7.29* | 21.21 ± 14.42 |

Mice were 14–20 weeks old. Numbers of mice analyzed are 5–11 per mouse line with the exception of two peritoneal cell measurements, where calculations are based on two samples (marked by asterisks).

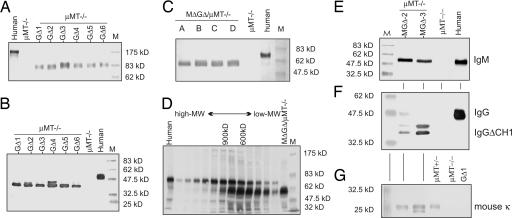

Fig. 5.

Prot G or concanavalin purified serum samples of six different GΔ lines (A and B), four MΔGΔ lines (C), and two MGΔ lines (E–G) in the μMT background run under nonreducing (A) and reducing conditions (B–G). The size of the chimeric IgG (B and F) and IgM (C and D) is consistent with a CH1 deletion and absence of LC. Mouse κ LC were normal size (G). Human serum was used as a positive control. (D) Superose 6 size fractionation of MΔ GΔ serum after mixing in a human IgM control under nonreducing conditions. Each fraction was analyzed by gel electrophoresis under reducing conditions. Fractions collected of the column are from left (high MW) to right (low MW). Controls are human serum alone (first lane) and mouse serum before mixing in the human IgM control serum (lane MΔGΔ serum). Size markers are indicated.

HCAb replace mouse (pre-)BCR in the BM.

During progression of large cycling into small resting pre-B cells, specific surface markers are down-regulated in a pre-BCR-dependent manner (22). To test whether chimeric HCAbs functionally replace the pre-BCR, various markers were analyzed. Pro-B cells express high cytoplasmic SLC, IL-7R and CD43, which are down-regulated upon pre-BCR expression and absent in mature B cells (Fig. 2B).

MΔGΔ/μMT or GΔ/μMT chimeric Ig+ B cells are SLC- and IL-7R-low, indicating that the chimeric HC IgG and IgM receptors function as a pre-BCR in down-regulating SLC and IL-7R. CD43 persists in MΔGΔ (not in GΔ) mice, perhaps due to increased B-1 B cell differentiation. CD2 and MHC class II are induced normally. The levels of the IL-2R/CD25, transiently present in pre-B cells, are very low on mature MΔGΔ or GΔ/μMT B cells as in WT (Fig. 2B). ic Igκ was absent in mature MΔGΔ or GΔ/μMT B cells (Fig. 2B) and was not induced in BM cultures upon IL-7 withdrawal after IL-7+ culture (data not shown). Finally, the chimeric HCAb+ B cell populations in MΔGΔ or GΔ mice consisted of cells generated in the BM (HSAhigh and AA4.1/CD93high) and cells matured in the periphery that are recirculating (HSAlow and CD93low) as in wild type.

Thus, chimeric HCAb IgG and IgM function as (pre-)BCR with respect to developmentally regulated markers. IgL chain is not induced (see below). Both VHHs are used for VDJ recombination, CH1 is absent and, importantly, CDR3 shows a large diversity (Fig. 2C).

Multiple Rearrangements and Allelic Exclusion.

MΔGΔ and GΔ hybridomas were made after immunization. Particularly, the five-copy GΔ line1 could have more than one rearrangement. Of the five different five-copy hybridomas, one rearranged one in frame copy; two hybridomas had two rearrangements, each with one out of frame; one hybridoma had two in-frame rearrangements; and one hybridoma had four rearrangements, with two in frame.

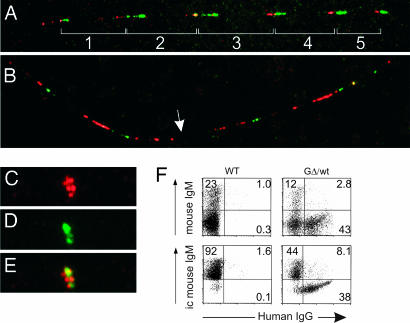

Two express two productive mRNAs (mass spectrometry confirmed the secreted HCAbs matching the cDNA; data not shown). We also carried out DNA fiber FISH on a hybridoma with one rearrangement and normal FISH on one with four rearrangements by using an LCR probe detecting each copy and a probe between VHH and D detecting only nonrearranged copies (Fig. 3A–E). Control cells showed five copies plus half a copy at each end (Fig. 3A), in agreement with Southern blots (data not shown), whereas the hybridomas show one and four rearranged copies, respectively (Fig. 3 B–E). Thus, multiple copies can rearrange successfully on the same allele.

Fig. 3.

DNA FISH and allelic exclusion of a five-copy chimeric GΔ locus. (A) Stretched chromatin fiber from lung cells of GΔ line1 carrying five intact copies (1–5) of the GΔ locus, flanked by half of a locus containing the LCR (red) and half of a locus containing VHH to J region (green). (B) Stretched chromatin fiber FISH of a hybridoma (G20) derived from GΔ line1 B cells where one copy has rearranged (white arrow). (C) Nonstretched DNA FISH of hybridoma T1 with the LCR probe (red). (D) Same as C with a probe between VHH and D (green). (E) Overlay of C and D. Note that T1 has four rearrangements visible because of the loss of four green signals with no loss of red signals. (F) Allelic exclusion in GΔ mice. Flow cytometric analysis of murine surface or intracellular (ic)μ H chain and chimeric IgG on total BM CD19+ cells from GΔ transgenic mice in a WT background and a nontransgenic WT control mouse displayed as dot plots. The % of cells within the quadrants is indicated. The average extracellular and intracellular double expressors after subtraction of the background were 1.5% and 5.8%, respectively (n = 9).

Moreover B220/CD19-positive BM cells of GΔ line1 transgenic mice in a WT background were analyzed for the expression of transgenic IgG and mouse IgM. Clearly, the GΔ B cells express either mouse Ig or chimeric Ig (Fig. 3F), showing allelic exclusion.

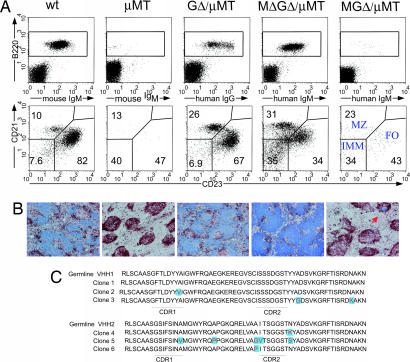

Splenic B cells.

Splenic B cell subpopulations were analyzed by using CD21/CD23 (Fig. 4A). GΔ CD21lowCD23low immature B cells were in normal ranges, and chimeric HC-IgG+ cells differentiated into follicular (FO; CD21+CD23+) and marginal zone (MZ; CD21highCD23low) B cells. In MΔGΔ, the immature B cells were increased, i.e., differentiation of HC-IgM expressing cells into FO and MZ B cells appear somewhat impaired. CD23 reduction was accompanied by increased CD43 and CD5 (data not shown), indicative of differentiation into B-1 B cells. The few chimeric IgM expressing B cells (also expressing mouse LC, see Fig. 5) in MGΔ mice had a FO/MZ distribution similar to MΔGΔ mice.

Fig. 4.

B cell populations in the spleen of WT, μMT, GΔ, MΔGΔ, and MGΔ mice. Data shown are representative of 4–8 mice examined in each group. (A Upper) FACS data of spleen cells, stained for mouse IgM, chimeric IgG, chimeric IgM versus B220. (A Lower) Flow cytometric analysis of B cell populations in spleen. Lymphoid cells were gated on forward and side scatter. Surface expression of B220 and the indicated Ig (A Upper) or the CD21/CD23 profile is displayed as dot plots and the % of cells within the indicated gates are given. CD21lowCD23low, immature B cells; CD21+CD23+, follicular B cells; CD21highCD23low, marginal zone B cells. (B) Histology of the spleen of WT, μMT, GΔ/μMT, MΔGΔ/μMT, and MGΔ/μMT mice. Immunohistochemical analysis is shown after 5-μm frozen sections were stained with αB220 (blue) for B cells and αCD11c/N418 (brown) for dendritic cells. Arrow indicates a small cluster of B cells in MGΔ spleen. (C) Sequence alignment of Peyer's patches cDNA showing that the transgenic locus undergoes hypermutation in the CDR1 and 2 regions. Sequences are from the transgenic locus GΔ with a CH1 deletion.

Spleen architecture in MΔGΔ and GΔ, but not MGΔ mice, is normal (Fig. 4B). As in wild type, germinal centers in B cell follicles are formed (data not shown) during T cell-dependent responses that in GΔ mice contain chimeric IgG+ cells. We confirmed hypermutation of the HCAb by cDNA analysis from B cells present in Peyer's patches. (Fig. 4C). Both VHHs are used. Thus, in GΔ and MΔGΔ mice, immature B cells migrating from BM differentiate into spleen FO and MZ B cells and undergo somatic hypermutation upon antigen challenge.

Single-copy loci rescue efficiently and CH1 absence is essential.

The GΔ line1 mice (Table 1) had five copies and, hence, the efficient rescue was related possibly to the copy number of the locus. A single-copy line generated from the GΔ line1 through breeding with a FlpeR line (23) gave the same B cell rescue (Table 1; Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Confirmation that a single copy of the locus is sufficient for rescue and that a CH1 region is inhibitory was obtained by cre-mediated deletion of the Cμ and Cδ from MGΔ line 3, resulting in a single-copy GΔ line (Fig. 8). This locus now rescues B cell development like the other GΔ lines. Thus, a CH1 region in Cμ inhibits B cell rescue, and copy number is not important.

Mouse Light Chains Do Not Rearrange in MΔGΔ and GΔ Mice.

Murine LC were absent in the MΔGΔ and GΔ mice by Western blots (data not shown, but see Fig. 2B and 5A) or FACS, suggesting that the LC genes do not rearrange as confirmed by comparing the Igκ locus germ-line signals in sorted splenic B220+ cells and liver DNA by Southern blots (Fig. 9, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Mouse LC remain in a germ-line configuration. In contrast, LC are present in the few chimeric Ig+ cells in the MGΔ/μMT mice (see Fig. 5G).

Thus, the chimeric HCAb expression in early B cell development in BM fails to signal for LC rearrangement. In this respect, HCAb lacking CH1 mimic a BCR rather than a pre-BCR, probably because of a failure to bind pseudo-LC (24).

Serum analysis.

Chimeric IgM was present in MΔGΔ and chimeric IgG in both MΔGΔ and GΔ serum. In nonimmunized adults, the chimeric IgM (≈50 μg/ml) and IgG (200–1,000 μg/ml) are present at levels comparable with those seen in WT or mice with a normal human IgH locus (25). All six GΔ mice had HCAb IgGs with a molecular mass of ≈80 kDa under nonreducing and ≈40 kDa under reducing conditions, consistent with HC dimers lacking a LC and each HC lacking CH1 (11 kDa shorter than the control human IgG; Fig. 5 A and B).

The MΔGΔ serum had multimeric HC-IgM. Under reducing conditions (Fig. 5C), all four lines had IgM with the molecular mass of a human IgM after subtraction of CH1. Serum also was fractionated (Fig. 5D, horizontal fractions) under nonreducing conditions, and each fraction was analyzed under reducing conditions (Fig. 5D, vertical lanes). When compared with the human pentameric 900-kDa IgM, the transgenic IgM is 600 kDa, consistent with a multimer lacking LC and CH1. Thus, MΔGΔ or GΔ mice produce multimeric IgM and/or dimeric IgG.

MGΔ Mice.

Some clustered B220-positive cells (<1% of the WT) are seen in MGΔ/μMT spleens (Fig. 4B), and serum chimeric IgM and IgGs were detected only after purification (Fig. 5 E and F). The IgM in these mice was normal size, whereas the IgGs are shorter because of CH1 deletion. Interestingly mouse κLC, presumably associated with the chimeric IgM, also were detected (Fig. 5G).

Immunization.

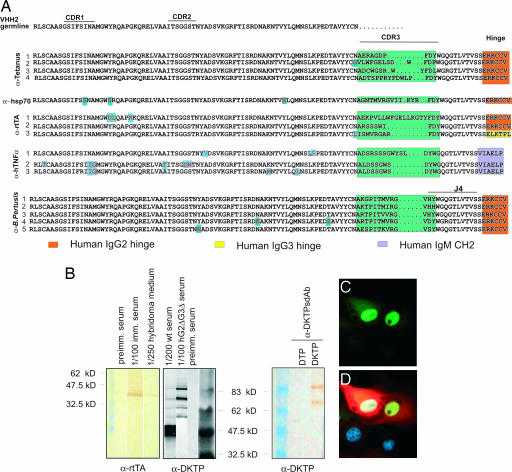

The GΔ/μMT mice were immunized with Escherichia coli hsp70, DKTP (Diphteria toxoid, whole cell lysate of Bordetella pertussis, Tetanus toxoid, and inactivated poliovirus types 1–3), and rtTA (26), the MΔGΔ mice with human TNFα. Antibodies were isolated from hybridomas or single-domain Ab (sdAb) phage display libraries.

Sequencing (Fig. 6A) showed that both IgG2 (seven of eight) and IgG3 [one of eight) were produced (the sdAb were isolated from a IgG2 library]. Different D and J regions were used. When comparing all 14 antibodies, it was evident that all J regions are used, but as in humans, JH4 is used most frequently. Surprisingly, all antibodies had VHH2 (with a Q rather than E at position 49; ref. 20). Clearly CDR3 provides most diversity (27). It varies between 10 and 20 aa (average of 13.6 aa), as in llamas and humans (28, 29). Although not at high frequency, the VHH were hypermutated. The 3α-hTNFα antibodies (Fig. 5) had different hypermutations in the CDR2 region.

Fig. 6.

Antibody properties. (A) Sequences of monoclonal antibody cDNAs specific for tetanus toxoid; HSP70, rtTA, and human TNFα. The top sequence is the germ-line VHH2 sequence. The CDR 1, 2, and 3 and hinge regions are indicated above the sequence. Different isotypes and classes are indicated by different colors on the right. The J regions that are used are indicated on the right. (B) Examples of Western blots by using the different HCAb (hybridomas, sera, and sdAb). (B Left) αrtTA serum and hybridoma medium, diluted 1/100 and 1/250. (B Center) αDKTP serum from WT and GΔ mice diluted 1/200 and 1/100. (B Right) α B. pertussis sdAb against vaccine containing B. pertussis antigen (DKTP) or lacking it (DTP, because we were unable to purchase purified B. pertussis antigen). (C and D) Immunostaining of a Tet− on cell line with a marker plasmid responding to rtTA by expressing a marker in cytoplasm (44). (C) Nuclei expressing rtTA (green). (D) Doxycycline-induced expression of the marker (red) in response to rtTA and DAPI nuclear staining (blue).

The HCAb are functional in regular assays as hybridoma supernatants and bacterial periplasmic fractions of sdAbs (Fig. 6). All were positive in ELISAs and in antigen detection on Western blots (Fig. 6B). We also tested the α-rtTA IgG in immunocytochemistry in a rtTA+ cell line (Fig. 6 C and D). The avidity of a number of the antibodies was high, although some were low. For example, binding studies of the α-rtTA antibody used in the immunocytochemistry (Fig. 6 C and D) by surface plasmon resonance analysis showed an association rate kon of (2.1 ± 0.002) × 105 (M−1s−1) and a dissociation rate koff of (4.1 ± 0.02) × 10−4 (s−1) resulting in a dissociation constant KD of 1.9 nM for anti-rtTA.

Discussion

Here, we reported that modified HCAb loci produce HCAb and rescue B cell development in μMT mice. Lack of CH1 is crucial for HCAb secretion, but the camelid splice mutation at the 3′ CH1 border (30) is insufficient for CH1 removal, thus more than this point mutation is required, at least in the human-type locus. VHH-IgM with CH1 blocks B cell development, probably because of ineffective assembly of surface IgM as a pre-BCR. In contrast, mice expressing a HC disease-like human μ protein develop normal CD43− pre-B cells in a SCID background independent of λ5 (9). Truncated IgM expressed on the B cell surface without L chains mimics pre-BCR signaling through self-aggregation (10).

Normally BiP chaperones the folding and assembly of antibodies by binding CH1 until it is replaced by (surrogate) LC (31). Although VpreB1 and 2 can bind normal IgM in the absence of λ5 (32), our results suggest that transgenic μ HC pairing with the Vpre protein does not take place when a CH1-containing μ HC is linked to a VHH, which would lead to a failure of B cell development (33). The MGS and MGΔ transgenic mice containing a CH1 would be able to form some pre-BCR-like complex that may lead to signaling, causing some expansion and developmental progression and explain why 30% of the B220-positive cells in BM have intracellular IgM (Fig. 2A). The few matured B cells in spleen of these mice may be explained by the recently described novel receptor complex lacking any SLC or LC (34).

When IgM is removed and Cγ 2 and 3 lack CH1, there is rescue of B cell development, showing that IgG can functionally replace IgM. IgG1 expression from the pro-B cell stage onwards, was shown to substitute for IgM in Rag2−/− B cell development (35). Recently, it also was shown that a prerearranged camelid IgG2a partially rescues B cell development in one transgenic line in a μMT (and a CΔ−/−) background (13). In our case, IgM or IgG lacking CH1 rescue B cell development in 10 of 10 independent lines. Moreover, we see no LC rearrangement and conclude that LC are not required for further B cell differentiation. The difference in our results and those of Zou et al. (13) may be explained by the level of expression of the locus (and, thus, signaling) because of the LCR on our constructs. Our results confirm that truncated μ HCAb lacking CH1 (24) or VH and CH1 (36) cannot associate with SLCs and fail to activate κ gene rearrangement.

Interestingly, one or more HC rearrangements occur in multicopy loci (Fig. 3). Two of the hybridomas, originating from two separate splenocytes gave two productive HCAb, confirming that expression of two antibodies in one B cell is not toxic (37). However, the prediction (37) that they would loose in competition with single antibody-producing cells under antigen challenge is not borne out by finding two double antibody-expressing cells of five hybridomas.

The (multicopy) locus is subject to and exerts allelic exclusion in WT background, because BM cells express either mouse or chimeric cell surface Ig. Few BM cells expressed both on the surface (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, a five-copy GΔ WT mouse has two mouse alleles with one Ig locus each and one allele with five chimeric HCAb loci. If alleles are chosen, there should be more mouse than chimeric Ig expression, and if genes are chosen, there should be more chimeric than mouse Ig expression. In fact, mouse Ig is expressed more often (44/38; Fig. 3F). Ignoring possible deviations from the random V use and a possible position effect on the transgenic locus, suggesting that the first choice is one of alleles.

Normally, a productive rearrangement down-regulates recombination to prevent rearrangement of the other allele. However, the multiple transgenic copies, when rearranged, exclude the mouse endogenous locus, but fail to exclude further rearrangement on the same open locus before RAG down-regulation. This process may involve a spatial component (“compartment”), in that the time before the RAGs are down-regulated would be sufficient to rearrange another gene in the locus because it would be in close proximity. The observation that other species with multiple loci on the same chromosome have more cells expressing two Abs (38) supports this argument. Alternatively multiple rearrangements may take place at the same time.

Importantly, we show that HCAb loci can be expressed successfully in mice. Antigen challenge results in antigen-specific chimeric HCAb of different classes (dependent on locus composition) expressed at levels comparable with WT or conventional human IgH transgenic mice (25). Only two VHHs were used, yet antibodies with diverse specificity were isolated successfully to almost all of the totally unrelated proteins we tested, demonstrating the efficiency and efficacy of diversity generated by CDR3 (27). Thus, having V(D)J recombination and in vivo selection provides an advantage over antibodies of fragments thereof from synthetic libraries. Hybridomas containing HCAb with a human effector function are generated easily. They can be used also for direct cloning and expression of sdAb, which can alternatively also be derived by phage display.

Thus, these mice open up new possibilities to produce human HCAb for clinical or other purposes, particularly in light of the evidence (4) that HCAbs may recognize “difficult” epitopes such as enzyme active sites. The restricted number of VH may explain why not all antigens were recognized; the polio and Diphteria proteins gave no response in GΔ mice, whereas WT control mice did (data not shown). Surprisingly, all antibodies had VHH2 lacking a conserved amino acid (39) at position 49 in contrast to VHH1 that has one and should be more soluble. Perhaps, VHH1 expression results in negative selection.

The addition of more VHs should lead to an even broader repertoire. Whilst it is preferable to avoid multiple copies on a single allele, it would be advantageous to have multiple alleles with a single copy of different VH regions to increase diversity. In such new loci, one can use either normally occurring (human) VH or VH engineered for increased solubility (18).

In conclusion, we show that antigen-specific HCAb of potentially any class can be produced in mice. By introducing soluble human VH domains in the locus, this technology allows the production of fully human HCAb of any class or fragments thereof in response to antigen challenge for use as therapeutic agents in man. By using different vertebrate loci, our technology also allows for production of antibodies from any vertebrate for use as reagents, diagnostics, or for the treatment of animals.

Materials and Methods

A standard genomic cosmid library was made from Lama glama blood. Two germ-line VHHs were chosen with hydrophilic amino acid codons at positions 42, 50, and 52 according to ImMunoGeneTics numbering (40), one with and one without a hydrophilic amino acid at 49. One is identical to IGHV1S1 (GenBank accession no. AF305944), and the other has 94% identity with IGHV1S3 (GenBank accession no. AF305946). PAC clone 1065 N8 contained human HC D and J regions, Cμ and Cδ, and clone 1115 N15 contained C γ3 (BACPAC Resource Center, Oakland, CA). Bac clone 11771 (Incyte Genomics, Palo Alto, CA) was used to obtain Cγ2 and the HC-LCR (41). Cγ3 and Cγ2 were subcloned separately into pFastBac (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The point mutation (G to A) (5) or deletion of CH1 was done by recombination (42). Similarly, frt and lox P sites were introduced 5′ to the Cμ switch region, and a second lox P site was placed 5′ to the Cγ2 switch region, resulting in MGS or MGΔ.

GS or GΔ were generated from MGS or MGΔ (Figs. 1 and 7) by cre recombination (43). MΔGΔ was obtained from MGΔ by deletion of the Cμ CH1 region through homologous recombination. The generation of transgenic mice, breeding, and genotyping, RT-PCR, flow cytometry, Ig gene arrangement, DNA FISH analysis, immunization and hybridoma production, sdAB library production and screening, immunocytochemistry, Western blots, gel filtration, and BIAcore measurements are described in Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Lede, K. Bezstarosti, J. Demmers, T. Nikolic, G. Dingjan, R. van Haperen, P. Rodriguez, and M. van de Corput (all from ErasmusMC) for materials and technical help during various stages of the project.

Abbreviations

- BM

bone marrow

- HC

heavy chain

- HCAb

HC-only antibody

- LC

light chain

- sdAb

single-domain antibody

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hamers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, Songa EB, Bendhman N, Hamers R. Nature. 1993;363:446–448. doi: 10.1038/363446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen VK, Hamers R, Wyns L, Muyldermans S. EMBO J. 2000;19:921–930. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen VK, Desmyter A, Muyldermans S. Adv Immunol. 2001;79:261–296. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(01)79006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauwereys M, Arbabi Ghahroudi M, Desmiter A, Kinne J, Holzar W, De Genst E, Wyns L, Muyldermans S. EMBO J. 1998;17:3512–3520. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.13.3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen VK, Hamers R, Wyns L, Muyldermans S. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:515–524. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolven BP, Frenken LG, van der Logt P, Nicholls PJ. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:98–101. doi: 10.1007/s002510050694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandt CR, Morrison SL, Birshtein BK, Milcarec C. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1270–1277. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.7.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fermand JP, Brouet JC. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:1281–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corcos D, Iglesias A, Dunda O, Bucchini D, Jami J. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2711–2716. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corcos D, Dunda O, Butor C, Cesbron JY, Lores P, Bucchini D, Jami J. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1140–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muyldermans S, Cambillau C, Wyns L. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:230–235. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01790-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen V, Zou X, Lauwereys M, Brys L, Bruggemann M, Muyldermans S. Immunology. 2003;109:93–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou X, Smith JA, Nguyen VK, Ren L, Luyten K, Muylderman S, Bruggeman M. J Immunol. 2005;175:3769–3779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitamura D, Roes J, Kuhn R, Rajewsky K. Nature. 1991;350:423–426. doi: 10.1038/350423a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macpherson AJ, Lamarre A, McCoy K, Harriman GR, Odermatt B, Dougan G, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:625–631. doi: 10.1038/89775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orinska Z, Osiak A, Lohler J, Bulanova E, Budagian V, Horak I, Bulfone-Paus S. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3472–3480. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3472::AID-IMMU3472>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasan M, Polic B, Bralic M, Jonjic S, Rajewsky K. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3463–3471. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3463::AID-IMMU3463>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies J, Riechmann L. Protein Eng. 1996;9:531–537. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riechmann L, Muyldermans S. J Immunol Methods. 1999;231:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Genst E, Silence K, Ghahroudi M, Decanniere K, Loris R, Kinne J, Wyns L, Muyldermans S. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14114–14121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conrath K, Vincke C, Stijlemans B, Schymkowitz J, Decanniere K, Wyns L, Muyldermans S, Loris R. J Mol Biol. 2005;350:112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Middendorp S, Dingjan GM, Hendriks RW. J Immunol. 2002;168:2695–2703. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farley FW, Soriano P, Steffen LS, Dymecki SM. Genesis. 2000;28:106–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iglesias A, Kopf M, Williams GS, Buhler B, Kohler G. EMBO J. 1991;10:2147–2155. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagner SD, Gross G, Cook GP, Davies SL, Neuberger MS. Genomics. 1996;35:405–414. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urlinger S, Baron U, Thellmann M, Hasan MT, Bujard H, Hillen W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7963–7968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130192197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu JL, Davis MM. Immunity. 2000;13:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vu KB, Ghahroudi MA, Wyns L, Muyldermans S. Mol Immunol. 1997;34:1121–1131. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(97)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zemlin M, Klinger M, Link J, Zemlin C, Bauer K, Engler JA, Schroeder HW, Jr, Kirkham PM. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:733–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conrath KE, Wernery U, Muyldermans S, Nguyen VK. Dev Comp Immunol. 2003;27:87–103. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(02)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knarr G, Modrow S, Todd A, Gething MJ, Buchner J. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29850–29857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seidl T, Rolink A, Melchers F. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1999–2006. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<1999::aid-immu1999>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mundt C, Licence S, Shimizu T, Melchers F, Martensson IL. J Exp Med. 2001;193:435–445. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.4.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su YW, Flemming A, Wossning T, Hobeika E, Reth M, Jumaa H. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1699–1706. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pogue SL, Goodnow CC. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1031–1044. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaffer AL, Schlissel MS. J Immunol. 1997;159:1265–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonoda E, Pewzner-Jung Y, Schwers S, Taki S, Jung S, Eolat D, Rajewsky K. Immunity. 1997;6:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eason DD, Litman RT, Luer CA, Kerr W, Litman GW. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2551–2558. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Genst E, Saerens D, Muyldermans S, Conrath K. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006;30:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lefranc M, Giudicelli V, Ginestoux C, Bodmer J, Muller W, Bontrop R, Lemaitre M, Malik A, Barbie V, Chaume D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;127:209–212. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mills F, Harindranath N, Mitchell M, Max E. J Exp Med. 1997;186:845–858. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imam A, Patrinos G, de Krom M, Bottardi S, Janssens R, Katsantoni E, Wai A, Sherratt D, Grosveld F. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;15:E65. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buchholz F, Angrand PO, Stuart AF. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3118–3119. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.15.3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dekker S, Toussaint W, Panayotou G, de Wit T, Visser P, Grosveld F, Drabek D. J Virol. 2003;77:12132–12139. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12132-12139.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.