Abstract

The purpose of this study was to compare the anesthetic efficacy of 2 bupivacaine solutions. Twenty-two volunteers randomly received in a crossover, double-blinded manner 2 inferior alveolar nerve blocks with 1.8 mL of racemic bupivacaine and a mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine, both 0.5% and with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine. Before and after the injection, the first mandibular pre-molar was evaluated every 2 minutes until no response to the maximal output (80 reading) of the pulp tester and then again every 20 minutes. Data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon paired test and the paired t test. No differences were found between the solutions for onset and duration of pulpal anesthesia and duration of soft tissue anesthesia (P > .05). It was concluded that the solutions have similar anesthetic efficacy.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, Levobupivacaine, Inferior alveolar nerve block, Anesthetic efficacy, Pulpal anesthesia

Racemic bupivacaine has been used as a local anesthetic in medicine and dentistry for many years. The 2 main indications for its use in dentistry are lengthy procedures and management of postoperative pain, as in endodontic, surgical, and periodontal procedures, among others.1 Although no case of toxicity has been documented in dentistry, a number of authors have reported its potent cardiac toxic effects, even in small doses.2 Studies that compared racemic bupivacaine and levobupivacaine have shown less toxicity for the latter.3,4

Since 2000, a new local anesthetic solution (0.5% mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine with and without epinephrine) has become commercially available in Brazil for medical use, according to the results obtained by Ferreira5, which showed faster onset of action and prolonged analgesia with this solution than with other mixtures of bupivacaine enantiomers. Considering the lower toxicity of levobupivacaine, the purpose of this study was to compare the anesthetic efficacy of racemic bupivacaine and the mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine, both in the concentration of 0.5% with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine.

METHODS

The Ethical Committee in Human Research at the Piracicaba Dentistry School, State University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil, approved this study; written consent was obtained from each subject. The sample size was based on a previous6 study and confirmed by using the software nQuery Advisor 4.0 for Windows. Twenty-two subjects (9 men and 13 women) who ranged in age from 21 to 51 years (average age, 25 years) participated in this study. All the subjects were in good health, and none were taking any medication that would alter pain perception, as determined by oral questioning and written health history. At clinical examination, the subjects presented the right first mandibular premolar free of caries, large restorations, periodontal disease, endodontic treatment, and history of trauma or sensitivity.7 A crossover, double-blinded study was conducted; the solutions were injected by the same clinician in 2 appointments at least 2 weeks apart.

Each subject was randomly assigned to receive inferior alveolar nerve blocks in the right side of the mandible with 0.5% racemic bupivacaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine (Neocaina, Cristália Produtos Químicos e Farmacêuticos Limitada, Itapira, São Paulo, Brazil) and 0.5% mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine (Novabupi, Cristália Prod. Quim. Farm. Ltda).

At the beginning of each appointment and before the injection, the right first mandibular premolar was tested 6 times with a pulp tester (Vitality Scanner model 2006, Analytic Technology, Redmond, Wash) to record baseline vitality. The mean value of the 6 readings was considered the baseline threshold. According to the manufacturer, a small portion of fluoride gel was applied to the probe tip, which was placed on the buccal side, midway between the gingival margin and the occlusal edge of the tooth to be tested. One trained person, blinded to the solutions administered, performed all the tests.

Because the solution of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine is not available in dental cartridges, 20-mL vials of both solutions tested were used. Under sterile conditions, 1.8 mL of the 0.5% mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine was drawn from a 20-mL vial into a sterile 5-mL Luer-Lok syringe. The same was done with the solution of 0.5% bupivacaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine. A conventional inferior alveolar nerve block (direct technique)1 was administered with a 27-gauge 1 1/4-in needle (Becton, Dickinson, and Co, Franklin Lakes, NJ) attached to a 5-mL Luer-Lok syringe (Becton, Dickinson Indústrias Cirúrgicas Limitada, Paraná, Brazil). The pH of the solutions was 2.81 for racemic bupivacaine and 2.78 for the mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextro-bupivacaine.

Every 2 minutes after the injection, the right first mandibular premolar was tested until no response from the subject to the maximum output (80 reading) of the pulp tester. After 2 readings of 80 without response, the tooth was tested every 20 minutes until return to baseline threshold. The response to the pulp test is characterized as a subjective sensation, such as pulsation, tingling, or pain.

The parameters evaluated were as follows. The first parameter was the onset of pulpal anesthesia, which is defined as the period between the end of the injection and the first of 2 consecutive 80 readings without response. The second parameter was the duration of pulpal anesthesia, which is defined as the period in which the subject had no response to the maximal output of the pulp tester (80 reading). Anesthesia was considered a failure if the subject never achieved 2 consecutive 80 readings without response.8 The third parameter was the duration of lip anesthesia, which is defined as the period from onset of anesthesia until return to normal sensation of the lip. The same person who performed the pulpal tests checked the beginning of lip anesthesia; the time to recover to normal sensation was recorded by the subjects.

The onset of pulpal anesthesia and duration of lip anesthesia data were analyzed nonparametrically through use of the Wilcoxon paired test. Duration of pulpal anesthesia data were analyzed using the paired t test. Comparisons were considered statistically significant at P < .05.

RESULTS

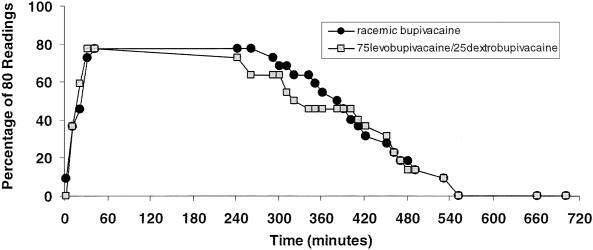

Five of the subjects did not achieve pulpal anesthesia (2 consecutive 80 readings), with the same incidence of failure of anesthesia with the 2 tested solutions. In 14 injections (7 for each solution), the onset of pulpal anesthesia was reached after 17 minutes. No statistically significant differences were found between the solutions with respect to onset of pulpal anesthesia (P = .92), duration of pulpal anesthesia (P = .48), and duration of lip anesthesia (P = .41). The onset and duration of pulpal anesthesia and the duration of lip anesthesia are listed in the Table. The incidence of pulpal anesthesia as determined by lack of response to the electrical pulp testing at maximal output (percentage of 80 readings) is shown in the Figure.

Duration of Lip Anesthesia and Onset and Duration of Pulpal Anesthesia (in Minutes) in the First Mandibular Premolar After Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block With the Local Anesthetic Solutions Tested*

Incidence of first mandibular premolar anesthesia (pulpal anesthesia) as determined by lack of response to electrical pulp testing (percentage of 80 readings without response) versus time for the 2 local anesthetic solutions tested.

DISCUSSION

The onset of anesthesia observed for racemic bupivacaine in this study was longer than that reported by others who studied the same solution for inferior alveolar nerve blocks (1.13 ± 0.83 minutes in the study by Laskin et al,9 1.44 ± 0.58 minutes in the study by Pricco,10 and 2.6 ± 2.4 minutes in the study by Dunsky and Moore11). When considering the “onset of surgical anesthesia,” the figures are higher (6.24 ± 1.69 minutes in the study by Pricco,10 8.1 ± 2.7 minutes in the study by Trieger and Gillen,12 and 12.6 ± 6.53 minutes in the study by Stolf Filho and Ranali13). Studies with the same experimental design used here have reported pulpal anesthesia onset times similar to those in this study, even when using anesthetics other than the long-acting ones.14,15 McLean et al14 and Hinkley et al15 have reported pulpal anesthesia onset times in the first mandibular premolar ranging from 10.0 to 13.7 minutes.

The results obtained for onset of pulpal anesthesia in this experiment, 14 minutes (median) for both solutions, could be explained due to the low pH of the solutions: 2.81 for racemic bupivacaine and 2.78 for the mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine. It is known that a solution with low pH will require more time to be buffered by the tissues, with sufficient molecules in the lipophilic freebase form able to diffuse across the nerve sheath.1

The duration of pulpal anesthesia observed for racemic bupivacaine in this study is similar to that related by Teplitsky et al16 (389.2 ± 144.1 minutes). Although the coefficient of variation may seem to be high (24.2% and 28.4% for racemic bupivacaine and the mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine solutions, respectively), the figures obtained in this study are within the range observed in the literature for this type of nerve block (19.2% to 71.4%).16,17

With respect to the duration of lip anesthesia, the studies with 0.5% bupivacaine show figures between 319 and 570 minutes, the latter closer to that obtained in this study for racemic bupivacaine (612 minutes) and the mixture of 75% levobupivacaine and 25% dextrobupivacaine solution (590 minutes).9,18 In vivo studies in animals19,20 for sciatic nerve block and in humans for epidural anesthesia and infiltration in medicine21–23 have not found any difference with respect to onset and duration of anesthesia between racemic bupivacaine and levobupivacaine.

The similarity of anesthesia efficacy obtained in this study for both solutions shows that the solution with a higher proportion of levobupivacaine could be used with efficacy and probably with less toxicity, since many authors have found levobupivacaine to be less toxic than racemic bupivacaine.3,4 More studies are necessary to compare racemic bupivacaine to levobupivacaine (as pure isomer) solutions for use in dentistry.

REFERENCES

- Malamed SF. St Louis, Mo: CV Mosby; 1997. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 4th ed. [Google Scholar]

- Bacsik CJ, Swift JQ, Hargreaves KM. Toxic systemic reactions of bupivacaine and etidocaine. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1995;79:18–23. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YF, Pryor ME, Mather LE, Veering BT. Cardiovascular and central nervous system effects of intravenous levobupivacaine and bupivacaine in sheep. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:797–804. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SG, Dominguez JJ, Frascarolo P, Reiz S. A comparison of the electrocardiographic cardiotoxic effects of racemic bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine in anesthetized swine. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:1308–1314. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira FMC. São Paulo, Brazil: Tese de Mestrado em Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo; 1999. Importância da Estereoisomeria na Atividade Bloqueadora Neuronal: Estudo Experimental com Anestésicos Locais em Nervo Ciático de Rato. [Google Scholar]

- Tofoli GR, Ramacciato JC, Oliveira PC, Volpato MC, Groppo FC, Ranali J. Comparison of effectiveness of 4% articaine associated with 1: 100,000 or 1: 200,000 epinephrine in inferior alveolar nerve block. Anesth Prog. 2003;50:164–168. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreven LJ, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ, Weaver J. An evaluation of an electric pulp tester as a measure of analgesia in human vital teeth. J Endod. 1987;13:233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(87)80097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeland DL, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ, Weaver J. An evaluation of volumes and concentrations of lidocaine in human inferior alveolar nerve block. J Endod. 1989;15:6–12. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(89)80091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin JL, Wallace WR, Deleo B. Use of bupivacaine hydrochloride in oral surgery: a clinical study. J Oral Surg. 1977;35:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pricco DF. An evaluation of bupivacaine for regional nerve block in oral surgery. J Oral Surg. 1977;35:126–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsky JL, Moore PA. Long acting local anesthetics: a comparison of bupivacaine and etidocaine in endodontics. J Endod. 1984;10:457–460. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(84)80270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trieger N, Gillen GH. Bupivacaine anesthesia and postoperative analgesia in oral surgery. Anesth Prog. 1979;26:20–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolf Filho N, Ranali J. Avaliação comparativa da bupivacaina e lidocaina em anestesia de pacientes submetidos a cirurgias de terceiros molares inferiores inclusos. Rev Assoc Paul Cir Dent. 1990;44:145–148. [Google Scholar]

- McLean C, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ. An evaluation of 4% prilocaine and 3% mepivacaine compared with 2% lidocaine (1:100.000 epinephrine) for inferior alveolar nerve block. J Endod. 1993;19:146–150. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)80510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkley AS, Reader A, Beck M, Meyers WJ. An evaluation of 4% prilocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine and 2% mepivacaine with 1:20,000 levonordefrin compared with 2% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine for inferior alveolar nerve block. Anesth Prog. 1991;38:84–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplitsky PE, Hablichek CA, Kushneriuk JS. A comparison of bupivacaine to lidocaine with respect to duration in the maxilla and mandible. J Can Dent Assoc. 1987;53:475–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keesling GR, Hinds EC. Optimal concentration of epinephrine in lidocaine solutions. J Am Dent Assoc. 1963;66:337–340. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1963.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman AG, Nordenram A. Marcaine in oral surgery: a clinical comparative study with Carbocaine®. Sven Tandlak Tidskr. 1966;59:745–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyhre H, Lang M, Wallin R, Renck H. The duration of action of bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, ropivacaine and pethidine in peripheral nerve block in the rat. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:1346–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirov M, Nau C, Mok WM, Strichartz G. Potency of bupivacaine stereoisomers tested in vitro and in vivo. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:744–755. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons G, Columb M, Wilson RC, Johnson RV. Epidural pain relief in labour: potencies of levobupivacaine and racemic bupivacaine. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:899–901. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Nielsen M, Klarskov B, Bech K, Andersen J, Kehlet H. Levobupivacaine vs bupivacaine as infiltration anaesthesia in inguinal herniorrhaphy. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:280–282. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader AM, Tsen LC, Camann WR, Nephew E, Datta S. Clinical effects and maternal and fetal concentrations of 0.5% epidural levobupivacaine versus bupivacaine for cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1596–1601. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]