Abstract

Purpose

Pretargeting has been attracting increasing attention as a drug delivery approach. We recently proposed Watson-Crick pairing of phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (MORF) for the recognition system in tumor pretargeting. MORF pretargeting involves the initial i.v. injection of a MORF-conjugated antitumor antibody and the subsequent i.v. injection of the radiolabeled complement. Our laboratory has reported on MORF pretargeting for diagnosis using 99mTc as radiolabel. We now report on the use of MORF pretargeting for radiotherapy in a mouse tumor model using 188Re as the therapeutic radiolabel.

Experimental Design

An initial tracer study was done to estimate radiation dose, and was followed by the radiotherapy study at 400 μCi per mouse with three control groups (untreated, MORF antibody alone, and 188Re complementary MORF alone).

Results

Tracer study indicated rapid tumor localization of 188Re and rapid clearance from normal tissues with a tumor area under the curve (AUC) about four times that of kidney and blood (the normal organs with highest radioactivity). Tumor growth in the study group ceased 1 day after radioactivity injection, whereas tumors continued to grow at the same rate among the three control groups. At sacrifice on day 5, the average net tumor weight in the study group was significantly lower at 0.68 ± 0.29 g compared with the three control groups (1 24 ± 0.31g, 1 25 ± 0.39 g, and 1 35 ± 0.41g; Ps <0.05), confirming the therapeutic benefit observed by tumor size measurement.

Conclusions

MORF pretargeting has now been shown to be a promising approach for tumor radiotherapy as well as diagnosis.

Pretargeting of tumor is often considered an improvement over the conventional targeting with radiolabeled antitumor antibodies. It involves the initial administration of a nonradioactive antibody with affinity both for a tumor antigen and for a small radiolabeled ‘‘effector’’ injected separately and later (1–4). Because the pretargeted antibody is not radioactive, sufficient time can be provided for the antibody to localize in tumor and clear elsewhere before being targeted by the radioactive effector in the second administration. Not only can a scintigraphic image of diagnostic quality be obtained within 1 to 3 hours after injection of the radioactivity compared with 1 to 3 days for conventional targeting with radiolabeled antibodies but, when pretargeting is considered for radiotherapy, the rapid clearance can translate into greatly reduced radiation exposure to normal organs (5, 6).

The recognition pairs that have been investigated for pretargeting applications include (strept)avidin/biotin (7), bispecific antibody/hapten (8), and oligomer/complementary oligomer (9). The latter is the most recent and has received the least attention thus far (10–12). Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (MORF) are a family of synthetic oligomers that are water soluble and reported to be stable both in vitro and in vivo (13, 14). They have been given to mice, rats, rabbits, and primates, and clinical trials of antisense MORFs are currently under way (AVI Bio Pharma, Inc., Corvallis, OR). Mutagenicity and teratogenicity studies have been done in vitro (13, 15) and toxicity studies have been conducted in rats and primates as well as in patients (13, 15, 16). The available evidence suggests that MORFs are nontoxic at the modest dosages considered herein. In this investigation, the antitumor antibody was conjugated with an 18-mer MORF and given first as the pretargeting agent followed at an appropriate time by the administration of the radiolabeled complementary MORF (cMORF) as the effector.

We have reported previously on the successful use of the MORF/cMORF recognition system for imaging with the diagnostic radionuclide technetium-99m (99mTc; refs. 17–19). Rhenium-188 (188Re) was selected as the therapeutic radionuclide for this investigation not only because of its attractive properties for radiotherapy but also because of its similar chemical properties to 99mTc, the nuclide often used for rhenium pretherapy studies. This similarity permits the use of the same labeling method and, more importantly, results in radiolabeled agents with similar, if not identical, properties. In particular, the stability of the 188Re radiolabel in the MAG3 chelator has been extensively investigated and found to be equally stable to that of 99mTc and, more importantly, suitably stable for radiotherapy trials (17, 20). We now report on tumor pretargeting with the therapeutic radionuclide 188Re and the first therapeutic trial in tumored mice.

Materials and Methods

The anti–carcinoembryonic antigen IgG antibody MN14 was a gift from Immunomedics (Morris Plains, NJ). The amine-derivatized MORF and its complement cMORF were purchased from Gene Tools (Philomath, OR). Their base sequences and molecular weights are as follows: MORF, 5′-TCTTCTACTTCACAACTA-C(O)-(CH2)2-amine (6,060 Da) and cMORF, 5′-TAGTTGTGAAGTAGAAGA-C(O)-(CH2)2-amine (6,318 Da). The C6-SANH [N-(6′-succinimidyl hexanoyl) 6-hydrazinonicotinamide acetone hydrazone; molecular weight, 403 Da] and C6-SFB [N-(6′-succinimidyl hexanoyl) 4-formylbenzamide; molecular weight, 360 Da] were from Solulink (San Diego, CA). NHS-MAG3 was synthesized in house (21). Commercial 9-mL Sephadex G25 columns were from NeoRx Corp. (Seattle, WA), whereas P4 Gel (medium) was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Float-A-Lyzers (molecular weight cutoff, 100,000 Da) for dialysis were from Spectrum Laboratories (Rancho Dominguez, CA). The 188W/188Re generator was purchased from Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Oak Ridge, TN).

Preparation of MORF-MN14 and labeling of cMORF with 188Re

Using the commercial Hydralink method, MORF-MN14 was prepared according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedure (22). The purity of the products in each step was monitored by size exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography with a Superose 12 column. The average number of MORFs per antibody was determined by adding a known excess of 99mTc-labeled cMORF to a known amount of MORF-MN14 as described previously (18).

The 188Re labeling of cMORF was scaled up from that previously described (20). Increasing the scale lowered the labeling efficiency somewhat to ~85%. The radiolabeled cMORF was used without purification because the impurity has been shown to clear from the whole body rapidly as the labeled cMORF (20).

Tracer study of 188Re-cMORF in pretargeted tumored mice

All animal studies were approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Worcester, MA). About 106 LS174T colon cancer cells were inoculated in the left thigh of each Swiss NIH nude mouse (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY). On day 13, when tumors were ~0.4 g, each mouse received via a tail vein 12.5 μg MORF-MN14 (1.15 MORF groups per antibody molecule) and 48 hours later 1.12 μg (25 μCi) of 188Re-labeled cMORF. These dosages were chosen to achieve the highest tumor accumulations based on earlier experiences (19). The kinetics of radioactivity distribution in normal organs and tumor was followed by sacrificing two animals at 1 and 3 hours and then one animal every 3 hours until 73 hours after radioactivity injection. At sacrifice by exsanguination following cardiac puncture under halothane anesthesia, blood and other organs were removed, weighed, and counted in a NaI(Tl) well counter (Cobra II automatic gamma counter, Packard Instrument Co., Meriden, CT). Blood and muscle were assumed to constitute 7% and 40% of body weight, respectively. The tumored thigh was also excised for counting but after the skin and as much as possible of the muscle and bone was removed. The radioactivity was attributed to the tumor because bone and muscle radioactivity was negligible. After the tumor thigh was counted, the tumor was dissected away and the remaining bone and muscle were weighed. This weight was subtracted to provide the net tumor weight.

Dosimetry study

Using the SAAM II simulation analysis and modeling program (23), the percentage of injected dosage per gram of organ (% ID/g) for each tissue was fitted to a three-component exponential function. The blood data were fitted first, and then the data for other organs were fitted by keeping the three exponents the same and adjusting only the coefficients of the three exponential terms. Figures 1 and 2D show some biodistribution data along with their produced best fit. For a unit administered radioactivity dosage, time-radioactivity curves were obtained by taking physical decay into account (half-life of 17.0 hours for 188Re). Analytic integrations of the time-radioactivity curves yielded the cumulated activity concentration per unit administered activity [area under the curve (AUC)] for each tissue.

Fig. 1.

Radioactivity accumulation in some normal organs over time after administration of 188Re-labeled cMORF in LS174T tumor-bearing mice that received MORF-MN14 2 days earlier. Values are presented individually for each animal. Solid line are the best fit by SAAM II simulation analysis.

Fig. 2.

A, radioactivity accumulation in tumor plotted against the time of sacrifice after administration of 188Re-labeled cMORF in LS174T tumor-bearing mice that received MORF-MN14 2 days earlier. B, tumor weights of pretargeted mice receiving tracer levels of 188Re-cMORF plotted against the time of sacrifice. C, tumor accumulations plotted against tumor weight corrected for tumor growth between administration of 188Re-cMORF and sacrifice. D, tumor accumulations corrected to the average tumor size of 0.36 g at T = 0.

The fundamental equation to calculate absorbed radiation doses was as follows (24):

where Dt is the radiation dose of the target organ, K is a unit conversion factor, Eβ is the mean β energy of 188Re, φβ (t←i) is the absorbed fraction of radiation from source organ i to the target organ t, AUC is in units of μCi h/g, and (mt/mi) is the mass ratio of target organ t to source organ i.

To facilitate comparison with reports in the literature, the radiation dose per unit injected activity was calculated using three models. (a) ‘‘Self-absorbed’’ model (25, 26): only radiation dose from the β particle was considered and 100% of its energy was assumed to be deposited in the source organ. The absorbed radiation dose per unit administered radioactivity in an organ was simply the product of the AUC, the mean energy of the β particle, and the unit conversion factor. (b) ‘‘MIRDOSE sphere’’ model (24): S values for spheres of various sizes were obtained from MIRDOSE 3.1 (Oak Ridge Associated Universities) with electron-photon contribution for sphere sizes larger than 0.5 g and only electron contribution to smaller tissues. For a unit of administered activity, the absorbed radiation dose to each organ was the product of the unit administered activity, residence time, and the S-value. (c) ‘‘Miller cross-organ’’ model (27): the absorbed dose per unit administered radioactivity was calculated based on a geometric nude mouse model. All organs were modeled as ellipsoids, and uniform radioactivity distribution was assumed in each organ. The self-organ absorbed fractions as well as the cross-organ absorbed fractions were based on Monte Carlo calculations. The cross-organ absorbed fractions were determined using as an approximation that the energy of β particles that escaped the source organ and deposited in the adjacent target organ was approximately proportional to the ratios of surface area that overlapped with the source organ. The tumor geometry was simulated as a sphere in the thigh, half-embedded in the carcass of the mouse and half-protruded above the carcass skin surface.

Therapy study of 188Re-cMORF in pretargeted tumored mice

Twenty-two Swiss NIH nude mice bearing carcinoembryonic antigen expressing LS174T tumor in the left thigh were divided into four groups. The ‘‘pretargeting therapy’’ group of six mice received both the MORF-MN14 and the 188Re-cMORF, the ‘‘MORF-MN14’’ control group of five mice received only the MORF-MN14, the ‘‘labeled cMORF’’ group of six mice received only the 188Re-cMORF, and the ‘‘untreated’’ group of five mice was untreated. Thus, at day 12 after tumor inoculation, the mice in both the pretargeting therapy and the MORF-MN14 control groups each received 55 μg MORF-MN14 (0.53 MORF groups per antibody), whereas the animals in the labeled cMORF group and the untreated group received nothing. At day 14, mice in the pretargeting therapy group and the labeled cMORF group each received 2.2 μg (380 μCi) of 188Re-labeled cMORF, whereas the other groups received nothing. All administrations were i.v. via a tail vein. At 17 hours after radioactivity injection, one mouse from the pretargeting therapy group and another from the labeled cMORF group were imaged simultaneously on a large field of view γ camera under ketamine-xylazine anesthesia. A 22-mm Lucite plastic sheet was placed between the mice and the detector to help minimize the Bremsstrahlung radiation emanating from the β rays of 188Re. Starting from day 10 and until sacrifice, the tumor thigh of each mouse was also measured for width, thickness, and length. At day 19, when some animals began to display discomfort due to tumor bulk, all mice were sacrificed and net tumor weights were obtained.

Results

Tracer study of 188Re-cMORF in pretargeted tumored mice

Table 1 lists the tumor weight and biodistribution of 188Re-cMORF in the tracer level pretargeting study for all mice in the order of increasing sacrifice time from 1 to 73 hours. Figure 1 presents the radioactivity accumulation over time in some of the normal organs. The solid line represents the best fit by SAAM II simulation analysis for all tissues, except tumor. Figure 2A shows the radioactivity accumulation over time in tumor, and a regression fit is not attempted because of the considerable fluctuation in values resulting from tumor growth during the study and from the animal to animal variation in tumor weight at the time of 188Re-cMORF administration.

Table 1.

Tumor size and biodistribution of labeled cMORF at different time in tumored mice pretargeted by MORF-MN14

|

% ID/g |

% ID |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse no. | Time (h) | Tumor size (g) | Tumor | Blood | Kidney | Liver | Spleen | Lung | Heart | Muscle | Salivary | Stomach | Small intestine | Large intestine |

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 7.27 | 5.43 | 5.11 | 1.95 | 1.04 | 2.06 | 1.32 | 0.70 | 2.13 | 1.28 | 2.32 | 0.35 |

| 2 | 3.00 | 0.55 | 7.64 | 3.04 | 4.51 | 1.42 | 0.69 | 1.23 | 0.73 | 0.33 | 2.95 | 1.57 | 0.56 | 1.66 |

| 3 | 6.15 | 0.35 | 8.22 | 2.97 | 3.53 | 1.27 | 0.77 | 1.26 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 1.93 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 1.78 |

| 4 | 9.08 | 0.44 | 8.04 | 2.34 | 2.34 | 1.17 | 0.80 | 1.11 | 0.89 | 0.31 | 1.15 | 2.36 | 1.36 | 5.65 |

| 5 | 12.22 | 0.56 | 6.20 | 1.87 | 2.04 | 1.12 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 0.86 |

| 6 | 15.12 | 0.40 | 8.12 | 1.74 | 2.39 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.97 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 1.66 |

| 7 | 18.25 | 0.53 | 8.30 | 1.36 | 2.53 | 1.04 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.81 |

| 8 | 21.00 | 0.15 | 13.44 | 2.04 | 1.79 | 0.94 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 0.60 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 1.56 |

| 9 | 23.83 | 0.44 | 9.11 | 1.31 | 1.42 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.34 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 1.80 |

| 10 | 27.08 | 0.35 | 11.11 | 1.41 | 1.68 | 1.15 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.41 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.21 |

| 11 | 30.27 | 0.30 | 12.55 | 2.12 | 1.80 | 1.27 | 0.87 | 1.13 | 0.49 | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.74 |

| 12 | 32.97 | 0.46 | 6.99 | 1.44 | 1.66 | — | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.46 | 0.19 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.41 |

| 13 | 36.08 | 1.09 | 4.74 | 0.68 | 1.43 | 1.30 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| 14 | 38.93 | 0.48 | 9.06 | 1.14 | 1.35 | 1.13 | 0.70 | 1.12 | 0.36 | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.49 |

| 15 | 42.00 | 0.63 | 7.73 | 1.02 | 1.31 | 1.46 | 0.99 | 0.69 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.31 |

| 16 | 45.93 | 0.74 | 7.51 | 0.78 | 1.52 | 1.34 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.27 |

| 17 | 48.00 | 0.69 | 7.66 | 0.67 | 0.98 | 1.33 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.21 |

| 18 | 51.02 | 0.55 | 10.59 | 1.04 | 1.33 | 1.23 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

| 19 | 54.77 | 0.72 | 9.55 | 0.81 | 1.04 | 1.26 | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| 20 | 57.00 | 0.65 | 10.21 | 0.86 | 1.33 | 1.36 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.11 |

| 21 | 60.30 | 0.99 | 5.04 | 0.56 | 1.14 | 1.29 | 0.59 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| 22 | 63.08 | 1.08 | 4.51 | 0.30 | 0.94 | 1.74 | 0.61 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| 23 | 66.00 | 0.48 | 9.77 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 1.32 | 0.90 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| 24 | 68.43 | 0.52 | 5.08 | 0.62 | 0.75 | — | 0.71 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| 25 | 72.50 | 0.64 | 2.92 | 0.59 | 1.01 | 1.21 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

To provide an accurate tumor AUC, corrections for tumor growth and size were applied to the tumor data of Fig. 2A. Figure 2B presents the measured tumor weights for all 25 animals plotted against their time of sacrifice. The positive slope of the regression line is a result of tumor growth during the 3-day tracer study. Because in a successful therapeutic study tumor does not grow and assuming that all tumors in this tracer study grew at the rate represented by the regression line, each tumor weight is extrapolated to T = 0 to provide an estimated value at the time of radioactivity administration. The average of all estimated weights at T = 0 is 0.36 g. The individual tumor accumulations plotted against these estimated tumor weights at T = 0 are shown in Fig. 2C. The decreasing tumor accumulation with increasing tumor size is a common observation (28–30). Finally, each individual tumor accumulation in % ID/g is corrected to 0.36 g and plotted against time of sacrifice as shown in Fig. 2D. The data points cluster around a value of ~8% ID/g now with diminished fluctuations, especially if the two data points at 68 and 73 hours are excluded. The latter two values probably reflect loss of radioactivity from tumor after ~60 hours.

Dosimetry calculations

The AUCs for animals receiving 1 μCi of 188Re-cMORF calculated from the results of the tracer study in pretargeted tumored animals are listed in Table 2. Absorbed doses obtained with each of the three models (self-absorbed, MIRDOSE sphere, and Miller cross-organ) are also listed in the table. As shown, only small difference in absorbed doses was observed among these models. The tumor-absorbed dose obtained from the ‘‘self-absorbed’’ model is 3.35 rad/μCi and higher than the 2.24 rad/μCi obtained using the Miller cross-organ model but similar to the 3.57 rad/μCi obtained using the MIRDOSE sphere model.

Table 2.

AUC and absorbed dose (rad) obtained with different method for 1 μCi (37 kBq) 188Re-cMORF injected into LS174T tumored mice pretargeted by MORF-MN14

| Organs | Tumor | Blood | Kidney | Liver | Spleen | Lung | Heart | Muscle | Salivary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (μCi h/g) | 2.03 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Self-absorbed | 3.35 | 0.77 | 0.95 | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.32 |

| MIRDOSE sphere | 3.57 | — | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.13 | — | 0.33 |

| Miller cross-organ | 2.24 | — | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 1.01 | 0.54 | — | 0.94 |

Because of important differences in tumor models, our values cannot be reliably compared with most reports from other laboratories investigating tumor radiotherapy by pretargeting. To our knowledge, only one investigation has been reported using the same radioisotope and the same LS174T tumor at a similar size (50–500 mm3; ref. 25). In that study, the absorbed dose was estimated only with the self-absorbed model as 1.73 rad/μCi for tumor, about half the 3.35 rad/μCi obtained with the same dosimetry model in this work. However, the absorbed dose ratios of tumor to normal tissues are generally in agreement.

Therapy study of 188Re-cMORF in pretargeted tumored mice

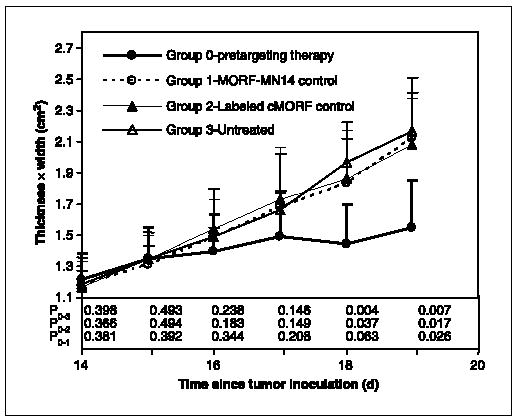

Of the three measurements of tumor size, tumor length was considered the least reliable. Figure 3 presents the average tumor size defined as the product of width and thickness of the tumor thigh starting on the 14th day after tumor implantation when radioactivity was administered. As shown, tumor growth was retarded only for the study animals starting 1 day after administration of radioactivity, whereas tumors for the three control groups continued to grow. The P values of the product of tumor width and thickness between study group and each of the three control groups are also included in the figure and show the decrease along with the time after radioactivity injection and the significant difference after 4 days (18 days since tumor inoculation). Figure 4 shows that the tumor weights in the study group at sacrifice on day 19 are approximately half that of the three control groups. Tumor weight differences between the study group and all the three control groups are statistically significant (P = 0.019, 0.019, and 0.032, Student’s t test) in contrast to the differences among the control groups (P = 0.664, 0.772, and 0.965). Clearly, tumor growth inhibition was the result of pretargeting with MORF-MN14 and 188Re-cMORF.

Fig. 3.

Average product of width and thickness of tumor thigh over time after radioactivity administration for mice from the pretargeting group and the three control groups. Points, mean (n = 5); bars, SD. Ps between study group and each of the three control groups. P0−1, for example, is the P value between the study group (group 0) and the control group receiving only MORF-MN14 (group 1).

Fig. 4.

A, histograms showing the average tumor weight at sacrifice for mice from the pretargeting group and the three control groups. Bars, SD. B, Ps are also presented.

Obtained simultaneously at 17 hours after radioactivity administration, the γ camera images of one mouse from the pretargeting therapy group and another from the radiolabeled cMORF control group with a similar tumor size are shown in Fig. 5. The strong radioactivity accumulations in tumor and in the regions of kidneys/liver in the study animal suggested in image were confirmed by animal sacrifice and dissection (data not presented).

Fig. 5.

Whole-body scintigraphic images of two nude mice with LS174T tumors in the left thigh at 17 hours after administration of 188Re-cMORF. Right, animal received MORF-MN14 2 days previously (pretargeting animal); left, animal did not receive the MORF-MN14 (labeled cMORF control).

Discussion

Conventional imaging of tumor-associated antigens with radiolabeled antitumor IgG antibodies suffers from slow localization and clearance and therefore can suffer from poor target/nontarget ratios. Reducing the molecular size of the radiolabeled antibody by, for example, substituting the F(ab′)2 fragment or even smaller single chain sFv fragments can improve on the slow localization and clearance but generally at the expense of lower target affinity. As an alternative to conventional tumor imaging, pretargeting restores the use of the high-affinity IgG antibodies by placing the radiolabel elsewhere. Pretargeting is under investigation using either streptavidin/biotin, bispecific antibody/hapten, or, as in our laboratory, MORF/cMORF oligomers with one member of the pair conjugated to the targeting antibody and the other radiolabeled as the effector. Each of these approaches has unique advantages and disadvantages. However, oligomers seem to be particularly well adaptable to pretargeting because of the high affinity of hybridization (31), the freedom to vary the chain length and base sequence as well as the oligomer type (DNAs, peptide nucleic acids, MORFs, etc.) to improve pharmacokinetics (10, 32, 33) and, in particular, the potential to improve pretargeting with amplification and with affinity enhancement, two extensions of conventional pretargeting still in early stages of investigation (10, 31, 34).

Ideally, the results presented in this report on the radiotherapy of tumored mice by MORF pretargeting should be compared with results obtained elsewhere with the two alternative popular pretargeting approaches, (strept)avidin/ biotin and bispecific antibody/hapten. The comparison should at least consider three important factors related to the therapeutic efficacy of a pretargeting approach (i.e., initial tumor accumulation, tumor retention, and normal organ background of the radioactivity).

The tumor accumulations of radioactivity in mouse models reported in the literature for different pretargeting approaches vary considerably, either less than (25, 26), comparable with (6), or much greater than (35–39) that reported herein. Unfortunately, because tumor accumulations are strongly dependent on tumor model, these values cannot in themselves be used to compare pretargeting approaches. Nevertheless, this large range in tumor accumulations by pretargeting requires comment. It may be commonly perceived that pretargeting should be capable of achieving tumor radioactivity accumulations superior to that achievable by the conventional targeting with radiolabeled antitumor antibodies. However, this is not true in most cases for reasons apart from the more rapid clearance of the effector from circulation. The absolute tumor accumulation (i.e., moles of radiolabeled agent per gram of tumor) for conventional antibody targeting is determined by targeting of the tumor antigenic sites with the radiolabeled antibody, whereas the absolute tumor accumulation by pretargeting is not only governed by the targeting of the tumor antigenic sites with the antibody but now is also limited by the targeting of the antibody with the radiolabeled effector. Thus, assuming one to one binding between antibody and effector, the best absolute accumulation that may be expected by pretargeting is equal to that of conventional radiolabeled antibody targeting. Nevertheless, because of the rapid targeting and rapid clearance of the effector, the advantage of pretargeting over radiolabeled antibody targeting is the potential for high target/normal tissue ratios achieved rapidly after radioactivity administration, a particular advantage in radiotherapy applications and/or when short radionuclide half-lives are involved. Moreover, by increasing the molar ratio of binding between effector and antibody by amplification, the tumor accumulation by pretargeting in principle can greatly exceed that of conventional targeting (34).

Retention of radioactivity in tumor is another factor that will greatly contribute to therapeutic efficacy. As shown in Figs. 1 and 2D, the 188Re radiolabel was retained for ~3 days, a period during which 95% of the 188Re radioactivity will have decayed. This retention is generally longer than that reported elsewhere (25, 26, 40, 41) and is probably due to both the stability of the radiolabel used herein and the high hybridization affinity between MORF and cMORF. Depending on chain length and base sequence, the hybridization affinity of MORFs may be comparable with that of streptavidin for biotin (1015/mol/L; ref. 42), whereas both pairs are superior to that of the bispecific antibodies for their haptens. Although lower affinity can encourage dissociation of the recognition complex in circulation with a resulting decrease in normal tissue background radioactivity levels, too low an affinity will also result in increased radioactivity clearance from tumor. Chmura et al. (43) have recently proposed a bispecific antibody pretargeting approach involving a covalent recognition mechanism with infinite affinity.

Finally, excessive background radioactivity in normal organs will interfere with imaging and, for radiotherapy, will determine the maximum tolerable dose. Ideally, these levels should decrease as rapidly as possible. An advantage of pretargeting lies in placing the radiolabel on a small effector designed to clear rapidly through the kidneys. In this respect, all three pretargeting approaches are comparable except for the streptavidin/biotin approach when the radiolabel is placed on streptavidin (44, 45). Therefore, background radioactivity levels in pretargeting approaches are basically influenced by residual targeting antibody in normal organs and in blood. Fortunately, at least for MORF pretargeting, the antibody deposited in normal organs, such as liver and spleen, rapidly becomes ‘‘invisible’’ to the effector (46, 47).

Conclusion

Under the conditions of the tracer level pretargeting study, the administration of 188Re-labeled cMORF in animals previously given MORF-MN14 resulted in tumor accumulations of ~8% ID/g in LS174T xenografts of ~0.4 g. Dosimetric estimates showed at least a 4-fold higher radiation dose to tumor than to normal tissues. In the subsequent therapy trial, the administration of ~400 μCi of 188Re provided definitive evidence of tumor growth inhibition. We conclude that, just as the MORF/cMORF pretargeting method is providing encouraging results when applied to tumor imaging with 99mTc as label, this MORF/cMORF approach holds promise for radiotherapeutic applications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gary L. Griffiths (Immunomedics) for providing the MN14 and the University of Massachusetts Medical School Tissue Culture Center for maintaining the LS174T tumor cells.

Footnotes

Grant support: NIH grants CA94994 and CA107360.

References

- 1.Goodwin DA. Tumor pretargeting: almost the bottom line. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:876–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbet J, Kraeber-Bodere F, Vuillez JP, et al. Pretargeting with the affinity enhancement system for radioimmunotherapy. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 1999;14:153–66. doi: 10.1089/cbr.1999.14.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boerman OC, van Schaijk FG, Oyen WJ, Corstens FH. Pretargeted radioimmunotherapy of cancer: progress step by step. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:400–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharkey RM. The direct route may not be the best way to home. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:391–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karacay H, Brard PY, Sharkey RM, et al. Therapeutic advantage of pretargeted radioimmunotherapy using a recombinant bispecific antibody in a human colon cancer xenograft. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7879–85. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharkey RM, Cardillo TM, Rossi EA, et al. Signal amplification in molecular imaging by pretargeting a multivalent, bispecific antibody. Nat Med. 2005;11:1250–5. doi: 10.1038/nm1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hnatowich DJ, Virzi F, Rusckowski M. Investigations of avidin and biotin for imaging applications. J Nucl Med. 1987;28:1294–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodwin DA, Meares CF, McTigue M, et al. Rapid localization of haptens in sites containing previously administrated antibody for immunoscintigraphy with short half-life tracers [abstract] J Nucl Med. 1986;27:959. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuijpers WH, Bos ES, Kaspersen FM, Veeneman GH, van Boeckel CA. Specific recognition of antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates by radiolabeled antisense nucleotides: a novel approach for two-step radioimmunotherapy of cancer. Bioconjug Chem. 1993;4:94–102. doi: 10.1021/bc00019a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Chang F, Zhang Y, et al. Pretargeting with amplification using polymeric peptide nucleic acid. Bioconjug Chem. 2001;12:807–16. doi: 10.1021/bc0100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rusckowski M, Qu T, Chang F, Hnatowich DJ. Pretargeting using peptide nucleic acid. Cancer. 1997;80:2699–705. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971215)80:12+<2699::aid-cncr48>3.3.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bos ES, Kuijpers WH, Meesters-Winters M, et al. In vitro evaluation of DNA-DNA hybridization as a two-step approach in radioimmunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3479–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Summerton J, Weller D. Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation, and properties. Anti-sense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:187–95. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mang’era KO, Liu G, Wang Y, et al. Initial investigation of 99mTc-labeled morpholinos for radiopharmaceutical applications. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1682–9. doi: 10.1007/s002590100637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iversen P. Phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers. In: Crooke ST, editor. Antisense drug technology. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2001. pp. 375–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iversen PL, Arora V, Acker AJ, Mason DH, Devi GR. Efficacy of antisense morpholino oligomer targeted to c-myc in prostate cancer xenograft murine model and a phase I safety study in humans. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2510–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu G, Mang’era K, Liu N, Gupta S, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Tumor pretargeting in mice using 99mTc-labeled morpholino, a DNA analog. J Nucl Med. 2002;43:384–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu G, He J, Dou S, et al. Pretargeting in tumored mice with radiolabeled morpholino oligomer showing low kidney uptake. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:417–24. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu G, He J, Dou S, Gupta S, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Further investigations of morpholino pretargeting in mice-establishing quantitative relations in tumor. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:1115–23. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1853-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu G, Dou S, He J, et al. Radiolabeling of MAG3-morpholino oligomers with 188Re at high labeling efficiency and specific radioactivity. Appl Radiat Isot. 2006 May 25; doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2006.04.005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winnard P, Jr, Chang F, Rusckowski M, Mardirossian G, Hnatowich DJ. Preparation and use of NHS-MAG3 for technetium-99m labeling of DNA. Nucl Med Biol. 1997;24:425–32. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He J, Liu G, Dou S, Gupta S, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. An improved method for covalently conjugating morpholino oligomers to antitumor antibodies [abstract] J Nucl Med. 2005;46:350P. doi: 10.1021/bc060208v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boston RC, Greif PC, Berman M. Conversational SAAM–an interactive program for kinetic analysis of biological systems. Comput Programs Biomed. 1981;13:111–9. doi: 10.1016/0010-468x(81)90089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stabin MG. MIRDOSE: personal computer software for internal dose assessment on nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:538–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gestin JF, Loussouarn A, Bardies M, et al. Two-step targeting of xenografted colon carcinoma using a bispecific antibody and 188Re-labeled bivalent hapten: biodistribution and dosimetry studies. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:146–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lubic SP, Goodwin DA, Meares CF, Song C, Osen M, Hays M. Biodistribution and dosimetry of pretargeted monoclonal antibody 2D12.5 and Y-Janus-DOTA in BALB/c mice with KHJJ mouse adenocarcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:670–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller WH, Hartmann-Siantar C, Fisher D, et al. Evaluation of β-absorbed fractions in a mouse model for 90Y, 188Re, 166Ho, 149Pm, 64Cu, and 177Lu radionuclides. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2005;20:436–49. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2005.20.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel JA, Pawlyk DA, Lee RE, Sharkey RM, Horowitz J, Goldenberg DM. Tumor, red marrow, and organ dosimetry for 131I-labeled anti-carcinoembryonic antigen monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1990;50:1039–42s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moshakis V, McIlhinney RAJ, Raghaven D, Neville AM. Localization of human tumour xenografts after i.v. administration of radiolabelled monoclonal antibodies. Br J Cancer. 1981;44:91–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1981.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchegger F, Haskell CM, Schreyer M, et al. Radio-labeled fragments of monoclonal antibodies against carcinoembryonic antigen for localization of human colon carcinoma grafted into nude mice. J Exp Med. 1983;158:413–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He J, Liu X, Zhang S, Liu G, Hnatowich DJ. Affinity enhancement bivalent morpholinos for pretargeting: surface plasmon resonance studies of molecular dimensions. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:1098–104. doi: 10.1021/bc050061s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu G, He J, Zhang S, Liu C, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Cytosine residues influence kidney accumulations of 99mTc-labeled morpholino oligomers. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 2002;12:393–8. doi: 10.1089/108729002321082465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu G, Zhang S, He J, et al. The influence of chain length and base sequence on the pharmacokinetic behavior of 99mTc-morpholinos in mice. Q J Nucl Med. 2002;46:233–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He J, Liu G, Gupta S, Zhang Y, Rusckowski M, Hnatowich DJ. Amplification targeting: a modified pretargeting approach with potential for signal amplification-proof of a concept. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1087–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Schaijk FG, Broekema M, Oosterwijk E, et al. Residualizing iodine markedly improved tumor targeting using bispecific antibody-based pretargeting. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1016–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Schaijk FG, Oosterwijk E, Soede AC, et al. Pre-targeting with labeled bivalent peptides allowing the use of four radionuclides: 111In, 131I, 99mTc, and 188Re. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3880–5S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Schaijk FG, Boerman OC, Soede AC, et al. Comparison of IgG and F(ab′)(2) fragments of bispecific anti-RCCxanti-DTIn-1 antibody for pretargeting purposes. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:1089–95. doi: 10.1007/s00259-005-1796-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Schaijk FG, Oosterwijk E, Molkenboer-Kuenen JD, et al. Pretargeting with bispecific anti-renal cell carcinoma × anti-DTPA(In) antibody in 3 RCC models. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Axworthy DB, Reno JM, Hylarides MD, et al. Cure of human carcinoma xenografts by a single dose of pretargeted yttrium-90 with negligible toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1802–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karacay H, McBride WJ, Griffiths GL, et al. Experimental pretargeting studies of cancer with a humanized anti-CEA × murine anti-[In-DTPA] bispecific antibody construct and a 99mTc-/188Re-labeled peptide. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:842–54. doi: 10.1021/bc0000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao Z, Zhang M, Axworthy DB, et al. Radioimmunotherapy of A431 xenografted mice with pretargeted B3 antibody-streptavidin and 90Y-labeled 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-N, N′, N″, N‴-tetraacetic acid (DOTA)-biotin. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5755–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chilkoti A, Tan PH, Stayton PS. Site-directed mutagenesis studies of the high-affinity streptavidin-biotin complex: contributions of tryptophan residues 79, 108, and 120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1754–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chmura AJ, Orton MS, Meares CF. Antibodies with infinite affinity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8480–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151260298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rusckowski M, Fritz B, Hnatowich DJ. Localization of infection using streptavidin and biotin: an alternative to nonspecific polyclonal immunoglobulin. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1810–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao Z, Zhang M, Kobayashi H, et al. Improved targeting of radiolabeled streptavidin in tumors pre-targeted with biotinylated monoclonal antibodies through an avidin chase. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:837–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodwin DA, Meares CF, Watanabe N, et al. Pharmacokinetics of pretargeted monoclonal antibody 2D12.5 and 88Y-Janus-2-(p-nitrobenzyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecanetetraacetic acid (DOTA) in BALB/c mice with KHJJ mouse adenocarcinoma: a model for 90Y radioimmunotherapy. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5937–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu G, Liu C, Zhang S, et al. Investigations of 99mTc morpholino pretargeting in mice. Nucl Med Commun. 2003;24:697–705. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200306000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]