In 1943 the Russian virtuoso pianist, composer, and conductor Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninov (1873-1943) became ill in the middle of a concert tour and was admitted to a hospital in Los Angeles. When cancer was diagnosed, he looked at his hands and whispered, ‘My dear hands... Farewell, my poor hands.’ Were his hands the key to his suffering?

Rachmaninov is perhaps best known for his second, C minor, piano concerto, popularized in the films Brief Encounter (1945) and The Seven Year Itch (1955); the adagio sostenuto provided inspiration for Eric Carmen's 1976 pop song All By Myself, later covered by Celine Dion and mimed with passion by Renée Zellweger in the opening scenes of Bridget Jones's Diary in 2001. The third, D minor, piano concerto, already popular, was given further exposure by David Helfgott, as portrayed in Shine (1996). In his lifetime Rachmaninov's prelude in C sharp minor was so popular as a concert encore that he grew to hate it. And works such as the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini and the Symphonic Dances cemented his popularity. His technical perfection was legendary. It was said that his large hands were able to span a twelfth (an octave and a half or, for example, a stretch from middle C to high G).

The size of his hands may have been a manifestation of Marfan's syndrome, their size and slenderness typical of arachnodactyly.1,2 However, Rachmaninov did not clearly exhibit any of the other clinical characteristics typical of Marfan's, such as scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and eye or cardiac complications. Nor did he express any of the clinical effects of a Marfan-related syndrome, such as Beal's syndrome (congenital contractural arachnodactyly), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, homocystinuria, Stickler syndrome, or Sphrintzen-Goldberg syndrome. There is no indication that his immediate family had similar hand spans, ruling out familial arachnodactyly. Rachmaninov did not display any signs of digital clubbing or any obvious hypertrophic skin changes associated with pachydermoperiostitis.

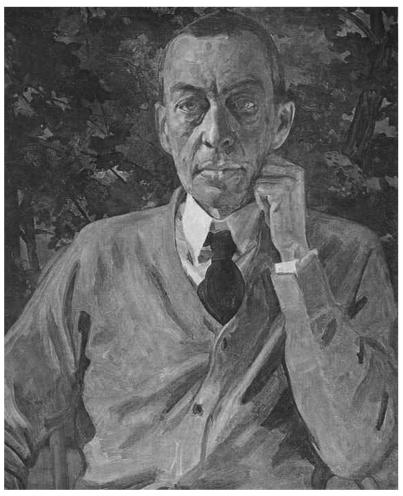

Acromegaly is an alternative diagnosis. From photographs of Rachmaninov in the 1920s and his portrait by Konstantin Somov in 1925 (Figure 1), at a time when he was recording his four piano concerti, the coarse facial features of acromegaly are not immediately apparent. However, a case can be made from later photographs.

Figure 1.

Portrait of Sergei Rachmaninov (1925) by Konstantin Somov; oil on canvas. The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Rachmaninov's repeated bouts of depression3 are also consistent with a diagnosis of acromegaly. On 27 March 1897, his First Symphony was poorly received in an under-rehearsed performance conducted by an inebriated Aleksandr Glazunov. This event, from which Rachmaninov fled in horror, is said to have triggered his first major episode of depression, which temporarily brought his composing career to a standstill: ‘all my hopes, all belief in myself, had been destroyed.’ It would not be until the latter half of 1900 that he returned to composition, with the help of a hypnotist, Dr Nikolai Dahl, to whom he dedicated his Second Piano Concerto, the second and third movements of which he brilliantly performed in December of that year. His second major bout of depression began during the Second World War, when he was living near Los Angeles, probably related to worries over the safety of one of his daughters and grief over the deaths of relatives and friends in the war.

During a heavy concert schedule in Russia in 1912, he interrupted his schedule because of stiffness in his hands. This may have been due to overuse, although carpal tunnel syndrome or simply swelling and puffiness of the hands associated with acromegaly may have been the cause. In 1942, Rachmaninov made a final revision of his troublesome Fourth Concerto but composed no more new music. A rapidly progressing melanoma forced him to break off his 1942-1943 concert tour after a recital in Knoxville, Tennessee. A little over five weeks later he died in the house he had bought the year before on Elm Drive in Beverly Hills. Melanoma is associated with acromegaly4,5 and may have been a final clue to Rachmaninov's diagnosis.

But then again, perhaps he just had big hands.

References

- 1.Wolf P. Creativity and chronic disease. Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943). West J Med 2001;175: 354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young DA. Rachmaninov and Marfan's syndrome. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293: 1624-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martyn B. Rachmaninov: Composer, Pianist, Conductor. Aldershot, England: Scholar Press, 1990

- 4.Popovic V, Damjanovic S, Micic D, et al. Increased incidence of neoplasia in patients with pituitary adenomas. The Pituitary Study Group. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1998;49: 441-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corcuff JB, Ogor C, Kerlan V, Rougier MB, Bercovichi M, Roger P. Ocular naevus and melanoma in acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;47: 119-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]