Abstract

Objectives To determine whether any particular intervention or combination of interventions is effective in the treatment, management and rehabilitation of adults and children with a diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome / myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME).

Design Substantive update of a systematic review published in 2002. Randomized (RCTs) and non-randomized controlled trials of any intervention or combination of interventions were eligible for inclusion. Study participants could be adults or children with a diagnosis of CFS/ME based on any criteria. We searched eleven electronic databases, reference lists of articles and reviews, and textbooks on CFS/ME. Additional references were sought by contact with experts.

Results Seventy studies met the inclusion criteria. Studies on behavioural, immunological, pharmacological and complementary therapies, nutritional supplements and miscellaneous other interventions were identified. Graded exercise therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy appeared to reduce symptoms and improve function based on evidence from RCTs. For most other interventions, evidence of effectiveness was inconclusive and some interventions were associated with significant adverse effects.

Conclusions Over the last five years, there has been a marked increase in the size and quality of the evidence base on interventions for CFS/ME. Some behavioural interventions have shown promising results in reducing the symptoms of CFS/ME and improving physical functioning. There is a need for research to define the characteristics of patients who would benefit from specific interventions and to develop clinically relevant objective outcome measures.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a debilitating condition characterized by fatigue on minimal exertion accompanied by a range of other symptoms such as headaches, sleep disturbance, cognitive difficulties and muscle pain.1,2 The severity of the symptoms varies widely both between patients and over time; in severe cases patients may be confined to bed or to a wheelchair. CFS affects both adults and children. The nomenclature of the condition and the overlap between CFS and myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) has been much debated. For this review we have used the term CFS/ME and included studies of people with a diagnosis of CFS/ME by any criteria.

The aetiology of CFS/ME remains uncertain and diagnosis is based on symptoms as reported by the patients. Case definitions developed for research purposes tend to be used to aid diagnosis, the most widely used being the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)2 and the UK (Oxford)1 criteria. Estimates of the prevalence of CFS/ME vary depending on the case definition used. In a study of 2376 primary care patients in England, 2.6% met criteria for CFS/ME but the prevalence fell to 0.5% when those with co-morbid psychological disorders were excluded.3 The UK Department of Health Working Party on CFS/ME4 estimated that a typical general practice with 10 000 patients is likely to have 30-40 patients with CFS/ME and that about half of these would require specialist services.

A variety of interventions have been used for the treatment and management of patients with CFS/ME and a number of groups have performed systematic reviews to assess the effectiveness of these interventions. Price and Couper5 assessed the effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) in adults and concluded that CBT appears to be an effective and acceptable treatment, although only three relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were found. Edmonds and colleagues reviewed RCTs of exercise therapy.6 Based on five RCTs they concluded that exercise therapy is a promising intervention, although they recommended more rigorous studies involving different patient groups and settings and a wider range of outcomes. A systematic review by Ross and colleagues examined how best to measure, monitor and treat disability in patients with CFS/ME.7 Disability was considered primarily in terms of ability to work. Although the authors found some small studies of interventions (including rehabilitation, CBT and graded exercise therapy [GET]) that reported improved employment outcomes, they concluded that no intervention has been proved to be effective in restoring the ability to work

More broadly, Mulrow and colleagues examined the definition and management of CFS/ME,8 while a review of all available interventions for the treatment and management of CFS/ME in both adults and children was carried out at the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD).9 These two reviews only covered the period up to 2001, and many studies of CFS/ME have been published since then. We recently carried out a number of systematic and scoping reviews on CFS/ME to inform the process of guideline development by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). In this paper we present an updated systematic review of the literature on interventions for the treatment and management of CFS/ME in adults and children.

METHODS

Literature search

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (1966 to May 2005), EMBASE (1980 to May 2005), PsycINFO (1872 to April 2005), CENTRAL (May 2005), Social Science Citation Index (1945 to 2005), Science Citation Index (1945 to 2005), Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings (1982 to 2005), PASCAL (May 2005), Inside Conferences (May 2005), AMED (1985 to January 2005), and HEED (June 2005). Individual search strategies were developed for each electronic database and details of these can be obtained from the authors. The search was broad, with the objective of identifying all studies of CFS/ME and related synonyms and covering several research questions. No language restrictions were applied. Additional references were sought by screening reference lists of retrieved articles, textbooks on CFS/ME, and stakeholder submissions from the NICE Guideline Development Group on diagnosis and management of CFS/ME.

Inclusion criteria and study selection

Two reviewers independently assessed all titles and abstracts identified from the searches for potential relevance to the review questions, and potentially relevant papers were retrieved in full. Two reviewers independently assessed these studies for possible inclusion, using the specified inclusion criteria. A third reviewer resolved differences.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were:

Intervention—any intervention or combination of interventions used in the treatment, management or rehabilitation of people with CFS/ME.

Population—adults and/or children aged five years or more with a diagnosis of CFS/ME based on any criteria.

Outcomes—all outcomes reported in included studies were considered.

Study design—only randomized or controlled clinical trials were eligible for inclusion.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from study reports by one reviewer and the results were checked by a second reviewer. Any discrepancies were resolved by reference to the original study, with a third reviewer being consulted if necessary. Only between-group comparisons were considered.

Validity assessment

The criteria for validity assessment described by Bagnall et al.9 and based on the CRD recommendations10 were used to allocate a validity score, ranging from 0 to 20, to each study. Assessment of validity was based on method of randomization and allocation concealment (randomized studies only); baseline comparability of groups; adjustment for confounding factors and appropriateness of the control group (controlled studies only); blinding; completeness of follow-up; handling of drop-outs and missing data; objectivity of outcome assessment; appropriateness of statistical analysis; whether the groups were treated identically apart from the named intervention; and sample size/statistical power. Validity was assessed by one reviewer and checked by another. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and reference to a third reviewer if necessary.

Data synthesis

Data were grouped by intervention into pre-specified broad categories and synthesized qualitatively. In evaluating the effects of interventions, a study was classified as showing some effect (positive or negative) of treatment if any of the outcomes measured showed a significant (P<50.05) difference between the treatment and control groups. Studies were classified as showing an overall effect of treatment if there was a significant difference between the treatment and control groups for more than one clinical outcome. Studies of pre-specified subgroups of patients (children and those with severe CFS/ME) were considered separately.

RESULTS

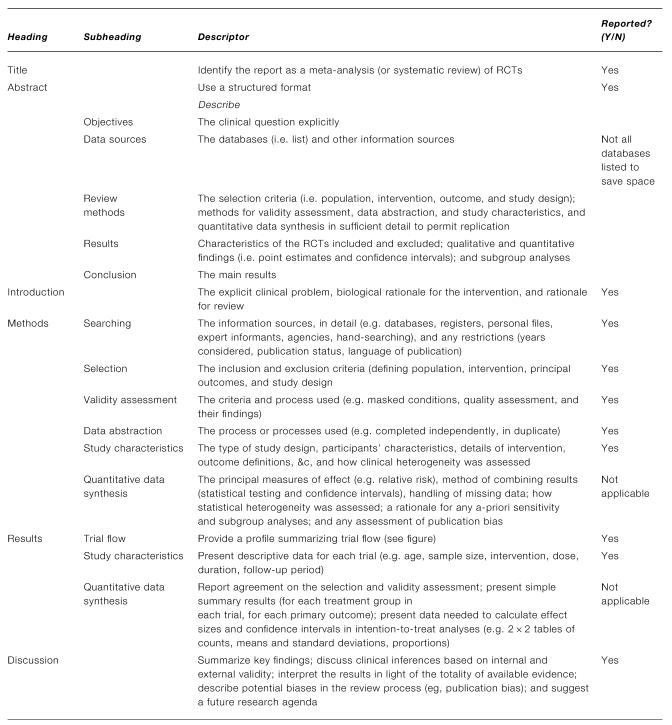

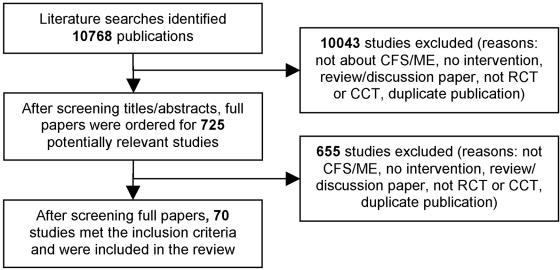

The overall literature search identified 10,768 items, of which 70 met the inclusion criteria for the review (Figure 1). Two studies included in the review by Bagnall et al. were excluded from the updated review, one because it included patients with chronic mononucleosis11 and one because a full report was subsequently published.12 Fifteen papers that were ordered as potentially meeting inclusion criteria had not arrived at the time of writing.13-27 One paper in the Russian language was identified as potentially meeting inclusion criteria but has not been translated.28 The paper is about a yeast extract supplement but it is unclear whether patients all had CFS.

Figure 1.

(A) QUORUM statement checklist of the systematic review. (B) QUORUM statement flow diagram of the systematic review. RCT, randomized controlled trial; CCT, controlled clinical trial

Of the studies included in the review, 59 were RCTs and the remainder non-randomized controlled trials (Table 1). Of the newly included studies (Table 2), 15 showed some beneficial effect of the intervention and eight showed an overall beneficial effect. Validity scores ranged from 2 to 19 for the included RCTs and from 0 to 14 for the controlled trials. Controlled trials generally scored less well than RCTs on all validity criteria. A high degree of heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes was evident.

Table 1.

Summary of results of studies included in the review. Controlled studies are shaded in the table, all other studies are RCTs

| Treatment | Number of patients | Outcomes investigated | Any effect | Overall effect | Validity score (Maximum 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioural | |||||

| CBT60 | 60 | PH; PS; QOL | + | + | 18 |

| CBT48 | 270 | PH; PS; QOL | + | + | 16 |

| CBT47 | 60 | PH; PS; QOL | + | + | 15 |

| CBT29 | 69 | PH; QOL | + | + | 16 |

| CBT + DLE61 | 90 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | + | = | 13 |

| Rehab62 | 47 | PH; QOL | + | + | 9 |

| Rehab63 | 130 | PH; PS; QOL | + | + | 8 |

| Rehab64 | 97 | PH; PS; QOL | + | = | 7 |

| CBT54 | 65 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 3 |

| CBT/rehab49 | 56 | PH; QOL | + | = | 2 |

| CBT65 | 44 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 1 |

| GET & Fluoxetine34 | 136 | PH; PS; QOL | + | = | 17 |

| GET32 | 66 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | + | + | 17 |

| GET33,53 | 148 | PH; PS; QOL | + | + | 17 |

| GET31 | 61 | PS; PH; LAB | + | + | 9 |

| GET30 | 49 | PH | + | + | 9 |

| Immunological | |||||

| Immunoglobulin50 | 71 | PH | + | + | 16 |

| Immunoglobulin66 | 30 | PH; LAB; QOL | = | = | 15 |

| Immunoglobulin67 | 49 | PS; QOL | + | = | 13 |

| Immunoglobulin68 | 99 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | = | = | 13 |

| Staphylococcus toxoid36 | 98 | PH | + | + | 14 |

| Staphylococcus toxoid69 | 28 | PS; QOL | + | = | 9 |

| Alpha interferon70 | 30 | LAB; QOL | + | = | 11 |

| Interferon71 | 20 | PH | = | = | 6 |

| Acyclovir51 | 27 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | − | = | 15 |

| Ampligen72 | 92 | RU; PH; PS | + | + | 12 |

| Terfenadine73 | 30 | PH; QOL | = | = | 12 |

| Gancyclovir74 | 11 | PH | = | = | 4 |

| Inosine pranobex35 | 16 | PH; LAB; QOL | + | = | 6 |

| Pharmacological | |||||

| Hydrocortisone75 | 32 | PH; QOL | + | = | 18 |

| Hydrocortisone76 | 70 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 14 |

| Hydrocortisone38 | 120 | PH; LAB | + | = | 2 |

| Hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone39 | 80 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | = | = | 14 |

| Fludrocortisone77 | 100 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | = | = | 18 |

| Fludrocortisone78 | 25 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 16 |

| Topical nasal corticosteroids40 | 28 | PH | = | = | 3 |

| Moclobemide79 | 90 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | = | = | 19 |

| Fluoxetine80 | 107 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 12 |

| Selegiline81 | 25 | PH; PS; QOL | + | = | 11 |

| Galantamine hydrobromide37 | 434 | PH; PS | = | = | 15 |

| Galanthamine hydrobromide82 | 49 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 9 |

| Oral NADH83 | 26 | QOL | + | + | 12 |

| Pharmacological | |||||

| Oral NADH84 | 20 | PH | = | = | 3 |

| Clonidine85 | 10 | PS | = | = | 12 |

| Phenelzine86 | 24 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 10 |

| Sulbutiamine87 | 326 | PH; QOL | = | = | 10 |

| Dexamphetamine88 | 20 | PH; QOL | + | = | 8 |

| Growth hormone89 | 20 | PH | = | = | 5 |

| Melatonin90 | 30 | PH; PS | + | + | 5 |

| Complementary / Alternative | |||||

| Homeopathy41 | 103 | PH | + | = | 17 |

| Any homeopathic remedy42 | 64 | QOL | = | = | 6 |

| Massage therapy91 | 20 | PH; PS; LAB | + | + | 9 |

| Osteopathy92 | 58 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 0 |

| Supplements | |||||

| General supplements93 | 53 | PH | = | = | 10 |

| General supplements94 | 42 | PH; QOL | = | = | 10 |

| General supplements95 | 12 | PH | = | = | 6 |

| Essential fatty acids*44 | 63 | LAB; QOL | + | + | 17 |

| Essential fatty acids*46 | 50 | PS; QOL | = | = | 16 |

| Magnesium45 | 34 | PH; PS; LAB; QOL | + | + | 15 |

| Liver extract96 | 15 | PH; PS; QOL | = | = | 10 |

| Acetyl-L-carnitine and propionyl-L-carnitine43 | 90 | PH; PS | + | + | 10 |

| Pollen extract97 | 22 | PH; PS; QOL; LAB | = | = | 9 |

| Acclydine and amino acids98 | 90 | PH; LAB | + | = | 3 |

| Medicinal mushrooms99 | 70 | PH | = | = | 3 |

| Other interventions | |||||

| Combination100 | 72 | PH | + | + | 19 |

| Combination101 | 71 | QOL | = | = | 3 |

| Combination102 | 52 | PS; QOL | + | = | 2 |

| Low sugar, low yeast diet | 57 | PH; PS | = | = | 11 |

| (Hobday et al., unpublished data) | |||||

| Buddy/mentor103 | 12 | PH; PS; QOL | + | = | 4 |

| Group therapy104 | 14 | PH; QOL | = | = | 1 |

+, positive effect of treatment; −, negative effect of treatment; =, no effect of treatment; rehab, rehabilitation; DLE, dialyzable leukocyte extract

Outcome codes: PH, physical; PS, psychological; LAB, laboratory and physiological; QOL, quality of life and general health; RU, resource use. Outcomes which showed a significant difference between intervention and control groups are highlighted in bold

Essential fatty acids (both studies) were 36mg gamma-linoleic acid (GLA), 17mg eicosapentanoic acid (EPA), 11mg docosahexanoic acid (DHA), 255mg linoleic acid (LA), plus 10 IU vitamin E

Table 2.

Results of new studies included in the updated review

|

Results

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Author (Year), number of participants | Physical | Psychological | Physiological | Quality of life and general health | Drop-outs/Adverse effects | Validity score |

| Behavioural | |||||||

| CBT | Whitehead (2002)54n=65 | Fatigue: no significant difference between groups | Anxiety and Depression: no significant differences between groups | Disability: no significant differences between groups | At 6 months, 8 in treatment group and 11 in control group were lost to follow-up | 3 | |

| Rehabilitation | Cox (2002)64n=97 | Physical functioning and fatigue: no significant differences between groups | Emotional distress: no significant differences between groups | Maintaining activity and accommodating to illness: significant difference in favour of treatment group (P<0.03) | 6 months after discharge, 14 in treatment group and 16 in control group did not return questionnaires | 7 (NB controlled trial) | |

| Rehabilitation | Cox (1999)63n=130 | Physical/functional status, fatigue, pain, symptoms: significant difference between groups for fatigue symptoms (P<0.02) and pain (P<0.05) | Perceived ability, anxiety, depression, emotional distress: significant difference between groups for emotional distress (P<0.03) | Illness management: significant difference in favour of treatment group (P<0.03) | 5 withdrew from experimental group, 18 from control group | 8 (NB controlled trial) | |

| Rehabilitation | Taylor (2004)62n=47 | Symptoms: significant interaction (P<0.05) | Quality of life: significant interaction (P<0.05) | No withdrawals | 9 | ||

| CBT | Stulemeijer (2005)29n=69 | Physical functioning, fatigue, symptoms: significant difference in favour of CBT group (P<0.003) | School attendance: significant difference in favour of treatment group (P=0.04) | 6 patients dropped out during treatment. 7 were missing from CBT group and 2 from control group at final assessment | 16 | ||

| Modified CBT | Viner (2004)49n=56 | CFS severity: better result in intervention group, significance not reported | Global wellness, school attendance: significantly better in treatment group (P<0.05) | No withdrawals | 2 (NB controlled trial) | ||

| GET | Moss-Morris (2005)30n=49 | CGI, fatigue: significant difference in favour of treatment group (P<0.03) | 3/25 dropped out of treatment and 3/24 did not return questionnaires at 12 weeks | 9 | |||

| GET | Wallman (2004)31n=61 | Fatigue: significantly better in treatment group (P=0.027) | Depression, anxiety: significantly better in treatment group (P=0.027) | Resting and target heart rate and blood pressure, exercise test values: comparisons not made between groups | One excluded after randomization because BMI too high to participate in exercise test. None reported during the study | 9 | |

| Immunological | |||||||

| Inosine pranobex | Diaz-Mitoma (2003)35n=16 | Symptoms, fibromyalgia tender points: no significant difference between groups | Cognitive function: no significant differences between groups | Immune function: significant improvements in treatment group (P<0.03) | Global severity, activities of daily living, Karnofsky Performance Scale: no significant differences between groups | 1 withdrawal in each group. Transient elevation of serum uric acid (presumably in treatment group) | 6 |

| Staphylococcus toxoid | Zachrisson (2002)36n=98 | Global impression, symptoms, pain: statistically significant difference in favour of treatment group for CGI (P<0.001) and ‘feeling good’ item on fibromyalgia impact questionnaire | 10 dropouts during study. 13 patients in the treatment group and 7 in the placebo group experienced side effects. | 14 | |||

| Pharmacological | |||||||

| Galantamine hydrobromide | Blacker (2004)37n=434 | Global impression, fatigue, symptoms: no significant differences between groups | Cognitive function: no significant difference between groups | 130 patients withdrew. 389 patients reported adverse events, of which 88 withdrew | 15 | ||

| Hydrocortisone | Cleare (2002)38n=120? | Fatigue: ‘significantly’ greater improvement in treatment group (P not reported) | Hormone levels: greater increase in cortisol response to HCRH in treatment group (significance not reported) | 2 | |||

| Hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone | Blockmans (2003)39n=80 | Fatigue: no significant differences between groups | Anxiety and depression: no significant differences between groups | Blood pressure: no significant differences between groups | SF-36, wellbeing: no significant differences between groups | 9 in treatment group and 11 in placebo group dropped out. Only one dropped out due to adverse events | 14 |

| Topical nasal corticosteroids | Kakumanu (2001)40n=28 | Fatigue, daytime sleepiness, muscle pain: no significant improvement with treatment | Daily activity: no significant improvement with treatment | 3 | |||

| Oral NADH | Santaella (2004)84n=20 | Symptoms: no significant difference between groups | 11 dropped out of 31 initially randomized. No adverse events were reported in treatment group | 3 | |||

| Dexamphetamine | Olson (2003)88n=20 | Fatigue, sleep: significant difference in favour of treatment group for fatigue (P<0.02) | SF36 scores: no significant difference between groups | Reduced food consumption reported by 5 patients in treatment group, one in placebo group | 8 | ||

| Clonidine | Morriss (2002)85n=10 | Cognitive function: no significant effects | One patient withdrew after GP prescribed fluoxetine | 12 | |||

| Melatonin vs phototherapy | Williams (2002)90n=30 | Symptoms, fatigue: improved sleep (P=0.03), vitality (P=0.016) and mental health (P=0.046) with melatonin, worsening of bodily pain (P=0.044) | Anxiety, depression: no significant effects of treatment | 12 of initial 42 patients withdrew, 10 due to time and social demands of the study | 5 | ||

| Complementary/Alternative | |||||||

| Homeopathy | Weatherley-Jones (2004)41n=103 | Fatigue, functional limitations: significant differences in favour of treatment group for fatigue (P=0.04) and some physical dimensions of the Functional Limitations Profile (P value not reported) | 11 withdrew from treatment arm (5 did not complete treatment) and 8 from placebo arm (6 did not complete treatment) | 17 | |||

| Supplements | |||||||

| Acetyl-L-carnitine and propionyl-L-carnitine | Vermeulen (2004)43n=90 | Global improvement, fatigue, pain: significant improvement in general fatigue in PLC (P=0.004) and combined group (P<0.001); significant improvement in mental fatigue in ALC group (P=0.015) | Attention, concentration: ‘significant’ improvements in all groups | 8 patients withdrew due to side effects and 8 withdrew due to lack of efficacy. | 10 | ||

| Acclydine and amino acids | De Becker (2001)98n=90 | Global improvement, symptoms: improvements seen in intervention group above control group but groups were not compared statistically | IGF-1 levels: significantly more improvement in intervention than placebo group (P<0.0002) | 3 (NB controlled trial) | |||

| Pollen extract | Ockerman (2000)97n=22 | Fatigue, sleep, symptoms: comparisons were not made between groups | Depression: comparisons were not made between groups | Erythrocyte fragility: comparisons were not made between groups | 1 withdrawal due to moving away. ‘Slight intestinal inconvenience’ was the only side effect for a few days in 1 or 2 patients | 9 | |

| RM-10: medicinal mushrooms | Rothschild (2002)99n=70 | Symptoms: improved more in the treatment group (measure of significance not presented) | 2 dropped out of treatment group, not reported for placebo group. | 3 | |||

| General supplements | Brouwers (2002)93n=53 | Fatigue, symptoms, improvement, functional impairment, activity: no significant differences between groups | 3 dropped out from the supplement group due to nausea, and one in each group for other reasons | 10 | |||

| Other interventions | |||||||

| Group therapy | Soderberg (2001)104n=14 | Fatigue: results not reported | Quality of life: comparisons were not made between groups | One withdrawal in control group | 1 | ||

| Low sugar low yeast diet | Hobday (2005, unpublished) n=57 | Fatigue: no significant differences between groups | Anxiety, depression: no significant differences between groups | General health: no significant differences between groups | 8 in the LSLY arm and 9 in the control arm were lost to follow-up | 11 | |

The evidence supporting the effectiveness of CBT has been strengthened by one recent good quality RCT in children and adolescents29 which found an overall positive effect of the intervention. CBT was associated with a significant positive effect on fatigue, symptoms, physical functioning and school attendance. Most other new studies of CBT and modified CBT have also favoured the treatment for one or more outcomes but these were either lower quality RCTs or non-randomized studies. GET has recently been studied in two moderate quality RCTs.30,31 These studies have broadened the evidence base for GET because, unlike earlier studies, they involved non-UK settings and patients who met the 1994 CDC case definition criteria for CFS/ME. As with CBT, the overall results of studies to date suggest that this intervention may have positive effects on the symptoms of CFS/ME. Improvements in measures of physical function were also found in all five RCTs of GET published to date.30-34 No severely affected patients were included in the studies of GET.

Two new studies of immunological therapies (a controlled trial of inosine pranobex35 and a relatively low quality RCT of staphylococcus toxoid36) were added to the updated review. Both of these treatments showed benefits for some outcomes but were also associated with relatively high levels of adverse events. Overall there is still insufficient evidence about the effectiveness of therapies of this type.

Treatment of CFS/ME with pharmacological therapies has given disappointing results in most cases. A recent large RCT of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galantamine hydrobromide37 found no significant differences between groups and 120 of 434 patients (27.6%) withdrew from the trial. An RCT of hydrocortisone published in 200238 found a significant difference between groups for fatigue, but this study scored poorly for validity. Two other recent studies of steroid treatment39,40 found no significant effect, in line with the mixed results reported in 2002.

The only new study of complementary/alternative therapies was an RCT of homeopathic treatment41 that showed significant differences favouring the treatment group for one of five measures of fatigue and one of five measures of functional limitations. This trial used rigorous methodology but there is also a published study showing no effect of homeopathic treatment42 and further studies are clearly required. A supplement of acetyl-l-carnitine and propionyl-l-carnitine showed an overall positive effect in one moderate quality RCT published in 2004.43 Other supplements (essential fatty acids44 and magnesium45) have also given promising results in single studies, although a later study of essential fatty acids failed to replicate the results of the first study.46 The trial of magnesium supplementation has apparently not been replicated. The evidence base for supplements and miscellaneous interventions for CFS/ME remains very limited.

There is limited evidence about adverse effects associated with behavioural interventions. Withdrawals from treatment in RCTs suggest that there may be an issue but the evidence is often difficult to interpret because of poor reporting. In one RCT of CBT,47 two patients attributed a deterioration in their symptoms to the effects of the treatment. Another RCT of CBT reported high withdrawal rates in all three intervention groups, but the reasons for withdrawal were not reported.48 In the study of GET by Fulcher and White,32 one patient in each group withdrew because of worsening symptoms. In the RCT of patient education to encourage GET,33 21 of 148 patients (14.1%) entering the trial withdrew; 19 of these were in the groups randomized to GET, but the reasons for withdrawal were not reported clearly enough to be sure how many were attributable to adverse events. Eleven patients withdrew because of adverse events in a RCT of GET with or without fluoxetine,34 but it is not clear which intervention group they were in. New studies of behavioural interventions included in the update (Table 2) did not report any withdrawals caused by adverse events, although again the reasons for withdrawal were often not reported.

Several studies of immunological/antiviral, pharmacological and nutritional interventions have reported withdrawals because of adverse effects, including recent studies of Staphylococcus toxoid,36 galanthamine hydrobromide37 and hydrocortisone/fludrocortisone.39

Recent studies of CBT29 and modified CBT49 in children and young people both reported that school attendance was significantly better in the treatment group compared with controls. One study supported the effectiveness of immunoglobulin treatment in children50 but this intervention may also have harmful effects.

DISCUSSION

Statement of principal findings

A number of RCTs suggest that behavioural interventions, including elements of CBT, GET and rehabilitation, may reduce symptoms and improve physical functioning of people with CFS/ME. Immunological and anti-viral treatments may have beneficial effects but are also associated with harmful side-effects. Most pharmacological treatments have not shown beneficial effects.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Review methodology

Our review was supported by a search of the literature that was designed to be as comprehensive as possible, with the objective of identifying all published studies of interventions for CFS/ME and related conditions that met pre-specified inclusion criteria. We searched for conference abstracts and dissertations as well as standard journal articles, and we attempted to locate unpublished reports and ongoing clinical trials.

Publication bias needs to be considered in any systematic review; studies with statistically significant or unexpected results are more likely to be published than those showing non-significant results. Various statistical tests to assess publication bias are available, notably funnel plots, but the reliability of these is questionable and they are no longer recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. We decided not to assess publication bias statistically for this reason and because of the wide range of interventions and outcomes included in the review. However, the fact that only one included study51 reported a negative effect of the intervention suggests that a degree of publication bias may be present in the CFS/ME literature.

A fundamental problem in evaluating interventions for CFS/ME is that the wide variety of outcome measures used in the included studies makes it difficult to compare the effects of interventions across studies. Even when studies evaluated the same outcome, they used a variety of scales and measures to do so. This heterogeneity made it impossible to combine studies by meta-analysis. Standardized measures of treatment effect (effect sizes) can be calculated when studies measure the same outcome in different ways but the data required for this (sample size, mean treatment effect and standard deviation in each group) were not reported in many included studies. We have summarized our results (Table 1) in a way designed to convey as much information as possible in a relatively small space, but this presentation has limitations. Achievement of statistically significant differences between groups may be influenced by sample size in the study and results may be statistically but not clinically significant. Our measure of ‘overall effect’ represents an attempt to deal with this issue by showing which studies reported a statistically significant treatment effect on two or more clinical outcomes. A summary of the results of all included studies showing the magnitude of treatment effects is available from the authors and will be included in an updated version of the report by Bagnall and colleagues9 that will be available from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/index.htm).

Included studies

As noted above, development of standardized and objective outcome measures and agreement on their use in studies remain largely unmet goals. There is also a lack of longterm follow-up data for most interventions, although a five-year follow-up of the RCT of CBT by Deale and colleagues showed maintained benefit of the intervention for several outcomes52 and a two-year follow-up of one RCT of GET was published in 2004.53 The studies included in our review also show a lack of uniformity in terms of case definitions for CFS/ME, study inclusion and exclusion criteria and the basic information provided about the participants. For example, baseline functional status and duration of illness are not always reported. It is therefore difficult to assess the generalizability of the findings of many of these studies.

Although we have discussed all the studies evaluating a particular intervention together, the treatment offered to patients receiving a particular type of therapy in practice may vary considerably, particularly for behavioural interventions. For example, in the CBT study by Stulemeijer et al.,29 participants in the intervention group received ten individual therapy sessions over five months in a hospital child psychology department, whereas in the study by Whitehead et al.54 the intervention was a form of ‘brief CBT’ delivered by general practitioners. Further standardization of methods for delivering behavioural interventions in research and practice would be desirable.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

This updated systematic review confirms and extends the conclusions of previous reviews in this area.5,6,8,9 Evidence reviews also informed guidelines for the treatment or management of CFS/ME published in Australia55 and the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) guidelines covering children and young people.56 The Australian guidelines concluded that CBT and GET ‘may be effective for some people with CFS’ (based on level 1 and 2 evidence, respectively). This is similar to the conclusions of our review. The recommendations for children and young people were largely developed by consensus because of a lack of specific evidence for this age group. GET and CBT were recommended for consideration based on extrapolation from studies in adults. The effectiveness of CBT for adolescents is supported by a recent high-quality RCT,29 although this had only 69 participants.

Meaning of the study and implications for clinicians/policy makers

Our results demonstrate that there are a considerable number of studies evaluating interventions for the treatment and management of CFS/ME and that many of them have used robust research methods; the majority of the included studies were RCTs and many of these were of high methodological quality (Table 1). However, RCTs generally scored poorly for concealment of treatment allocation and many failed to use an intention-to-treat analysis. These issues should be addressed in designing future clinical trials of interventions for CFS/ME. In view of the chronic nature of CFS/ME, future trials should be designed, as far as practicable, to collect long-term data on effectiveness and adverse events.

A number of issues may limit the uptake and availability of effective interventions for CFS/ME. Behavioural interventions require the participation of trained therapists and this may raise issues both of cost and the availability of personnel. This is particularly true for CBT, which is regarded as a valid therapy option for a range of conditions. Improving the organization and delivery of psychological therapies has been identified as a priority for the UK National Health Service.57

Unanswered questions/further research

Homeopathy and supplements (essential fatty acids and magnesium) have shown beneficial effects but only in one or two trials and further rigorous trials of these interventions would be helpful. Similarly, very few studies have assessed the effectiveness of interventions for children and young people and for severely affected patients. No rigorous evaluations of pacing were identified. A large trial known as PACE (Pacing, Activity and Cognitive behaviour therapy: a randomized Evaluation), involving patients attending specialist CFS/ME clinics across the UK, is underway and is due for completion in 2009. This trial is designed to compare specialist medical care against specialist medical care with the addition of adaptive pacing therapy, CBT or GET.

Patient perceptions and preferences regarding interventions have been investigated but are not generally reported in studies of effectiveness. Some studies of behavioural interventions have reported significant rates of withdrawal from treatment or loss to follow-up, as high as 20-40% in some studies.48,54 Withdrawals not related to adverse events may reflect patient dissatisfaction with treatment. Our review did not find any new evidence of adverse effects (sufficient to cause withdrawal from treatment) associated with GET or CBT. However, reasons for withdrawals were often poorly reported and should be investigated in more detail in future studies.

The protocols for many clinical studies require patients to attend a clinic for treatment and/or assessment. These conditions may exclude people severely affected with CFS/ME from taking part and hence bias the sample towards those with less severe symptoms. Surveys by patient organizations highlight the fact that those with the worst symptoms often receive the least support from health and social services.58 The balance between effectiveness and adverse effects of interventions may be different in more severely affected compared with less severely affected patients and methods of delivery/doses may need to be different. Research to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for severely affected patients should be considered a priority. The FINE (Fatigue Intervention by Nurses Evaluation) trial is designed to evaluate a pragmatic rehabilitation therapy delivered by nurses in patients' homes, and hence accessible to severely affected patients.59 This trial is expected to end in 2008.

Acknowledgments We thank Vickie Orton for carrying out the literature searches and Paul Wilson for helpful comments.

Authors' contributions Carol Forbes prepared the project proposal and managed the project. All authors participated in designing the study, selection of studies for the review, data extraction, data analysis and interpretation, and writing the paper, and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor Duncan Chambers is guarantor for this paper.

Ethical approval Was not required.

Funding/Support This project was funded by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence who commissioned the National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care (part of the Royal College of General Practitioners) to produce guidelines for ‘The Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or Encephalopathy) in Adults and Children’. The work forms part of the independent synthesis of research evidence to support the development of these guidelines. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NCC-PC, RCGP or the Institute. The funding source had no influence on study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests None declared.

References

- 1.Sharpe MC, Archard LC, Banatvala JE, et al. A report—chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research. J R Soc Med 1991;84: 118-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG, Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1994;121: 953-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, Wallace P, Wright D. The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: A prospective primary care study. Am J Public Health 1997;87: 1449-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CFS/ME Working Group. A report of the CFS/ME Working Group: Report to the Chief Medical Officer of an Independent Working Group. London: Department of Health, 2002

- 5.Price JR, Couper J. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1998: CD001

- 6.Edmonds M, McGuire H, Price J. Exercise therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2004:CD003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ross SD, Estok RP, Frame D, Stone LR, Ludensky V, Levine CB. Disability and chronic fatigue syndrome: a focus on function. Arch Intern Med 2004;164: 1098-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mulrow CD, Ramirez G, Cornell JE, Allsup K. Defining and managing chronic fatigue syndrome. Evidence Report: Technology Assessment (Summary) 2001: 1-4 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Bagnall A-M, Whiting P, Wright K, Sowden AJ. The Effectiveness of Interventions Used in the Treatment/Management of chronic Fatigue Syndrome and/or Myalgic Encephalomyelitis in Adults and Children. York, UK: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2002: Report No 22

- 10.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: CRD's Guidance For Those Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews. 2nd edn. York: NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2001: Report No 4

- 11.DuBois RE. Gamma globulin therapy for chronic mononucleosis syndrome. AIDS Res 1986;2(Suppl 1): S191-5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weatherley-Jones E, Thomas K. A randomised, controlled trial of homeopathic treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome [abstract]. 17th Annual Meeting of the International Society of Technology Assessment in Health Care: Building Bridges Between Policy, Providers, Patients and Industry. June 3-6 2001: 67

- 13.Siddiqui M, Kadri NN, Hee TT, et al. Clonazepam: an effective treatment of neurally mediated symptoms in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Chest 2000;118: 219S [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoni MH, Weiss D. Do stressors and stress management intervention affect physical symptoms and physiological functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome? Psychosom Med 2002;64: 5A [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antoni M, Chadler T. Symposium synopsis: The effects and underlying mechanisms of cognitive behavioral interventions in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Psychosom Med 2002;64: 5 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bazelmans E, Prins J, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive behavior therapy for active and for passive CFS patients/Cognitieve gedragstherapie bij relatief actieve en bij passieve CVS-patienten. Gedragstherapie 2002;35: 191-204 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleichhardt G, Timmer B, Rief W. Predictors for short- and long-term outcome in patients with somatoform disorders after cognitive-behavioral therapy. Zeitschrift Fur Klinische Psychologie Psychiatrie Und Psychotherapie 2005;53: 40-58 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janu L. The effect of care on patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. The open randomized comparison of three antidepressants. J Psychosom Res 2002;52: 328-28 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurek JN. Treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome with methylphenidate. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2001;61: 5 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberman S. Antiviral intervention for chronic fatigue syndrome. Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients 2004;248: 74-6 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schollmann C. Sage flower extract against fatigue syndrome and iron deficiency. Arztezeitschrift fur Naturheilverfahren 2001;42: 700+02 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strang JM. Treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome: a cognitive-behavioral approach to enhance personal mastery. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences 2002;63: 1 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Surawy C, Roberts J, Silver A. The effect of mindfulness training on mood and measures of fatigue, activity, and quality of life in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome on a hospital waiting list: a series of exploratory studies. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 2005;33: 103-09 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Hoof E, Coomans D, De Becker R, De Meirleir K, Cluydts R. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic systemic infections in chronic fatigue syndrome. Int J Psychophysiol 2002;45: 82-83 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Hoof E, Coomans D, De Becker P, Meeusen R, Cluydts R, De Meirleir K. Hyperbaric Therapy in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2003;11: 37-49 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldman PN. Vitamin therapy in the treatment of depression associated with chronic fatigue syndrome. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2001;61: 5 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright B, Ashby B, Beverley D, et al. A feasibility study comparing two treatment approaches for chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents. Arch Dis Child 2005;90: 369-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dotsenko VA, Mosiichuk LV, Paramonov AE. [Biologically active food additives for correction of the chronic fatigue syndrome]. Vopr Pitan 2004;73: 17-21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stulemeijer M, de Jong LW, Fiselier TJ, Hoogveld SW, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;330: 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss-Morris R, Sharon C, Tobin R, Baldi JC. A randomized controlled graded exercise trial for chronic fatigue syndrome: outcomes and mechanisms of change. J Health Psychol 2005;10: 245-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallman KE, Morton AR, Goodman C, Grove R, Guilfoyle AM. Randomised controlled trial of graded exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. Med J Aust 2004;180: 444-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fulcher KY, White PD. Randomised controlled trial of graded exercise in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ 1997;314: 1647-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell P, Bentall RP, Nye FJ, Edwards RH. Randomised controlled trial of patient education to encourage graded exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ 2001;322: 387-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wearden AJ, Morriss RK, Mullis R, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment trial of fluoxetine and graded exercise for chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172: 485-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diaz-Mitoma F, Turgonyi E, Kumar A, Lim W, Larocque L, Hyde BM. Clinical improvement in chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with enhanced natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity: the results of a pilot study with Isoprinosine. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2003;11: 71-93 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zachrisson O, Regland B, Jahreskog M, Jonsson M, Kron M, Gottfries CG. Treatment with staphylococcus toxoid in fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome-a randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Pain: EJP 2002;6: 455-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blacker CVR, Greenwood DT, Wesnes KA, et al. Effect of galantamine hydrobromide in chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292: 1195- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleare A. Hydrocortisone treatment in CFS. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2002;5(Suppl 1): S35 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blockmans D, Persoons P, Van Houdenhove B, Lejeune M, Bobbaers H. Combination therapy with hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone does not improve symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Am J Med 2003;114: 736-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kakumanu S, Mende C, Lehman E, Yeageer M, Craig T. The effect of topical nasal corticosteroids in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107: S153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weatherley-Jones E, Nicholl JP, Thomas KJ, et al. A randomised, controlled, triple-blind trial of the efficacy of homeopathic treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res 2004;56: 189-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Awdry R. Homeopathy may help ME. Int J Alternat Complement Med 1996;14: 12-6 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vermeulen RC, Scholte HR. Exploratory open label, randomized study of acetyl- and propionylcarnitine in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom Med 2004;66: 276-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Behan PO, Behan WM, Horrobin D. Effect of high doses of essential fatty acids on the postviral fatigue syndrome. Acta Neurol Scand 1990;82: 209-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox IM, Campbell MJ, Dowson D, Davies S, Walden RJ. Magnesium and chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet 1991;337: 1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warren G, McKendrick M, Peet M. The role of essential fatty acids in chronic fatigue syndrome. A case-controlled study of red-cell membrane essential fatty acids (EFA) and a placebo-controlled treatment study with high dose of EFA. Acta Neurol Scand 1999;99: 112-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharpe M, Hawton K, Simkin S, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for the chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ 1996;312: 22-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prins JB, Bleijenberg G, Bazelmans E, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001;357: 841-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Viner R, Gregorowski A, Wine C, et al. Outpatient rehabilitative treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME). Arch Dis Child 2004;89: 615-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowe KS. Double-blind randomized controlled trial to assess the efficacy of intravenous gammaglobulin for the management of chronic fatigue syndrome in adolescents. J Psychiatr Res 1997;31: 133-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Straus SE, Dale JK, Tobi M, et al. Acyclovir treatment of the chronic fatigue syndrome. Lack of efficacy in a placebo-controlled trial. N Engl J Med 1988;319: 1692-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deale A, Husain K, Chalder T, Wessely S. Long-term outcome of cognitive behavior therapy versus relaxation therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158: 2038-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Powell P, Bentall RP, Nye FJ, Edwards RH. Patient education to encourage graded exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome. 2-year followup of randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2004;184: 142-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whitehead L, Campion P. Can general practitioners manage Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? A controlled trial. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2002;10: 55-64 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical practice guidelines -2002. Med J Aust 2002;176: S19-55 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Evidence Based Guideline for the Management of CFS/ME (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalopathy) in Children and Young People. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 2004

- 57.Department of Health. Organising and Delivering Psychological Therapies. London: Department of Health; 2004

- 58.Action for M.E. Severely Neglected: M.E. in the UK—Membership Survey. London: Action for M.E.; 2001

- 59.Wearden AJ, Riste L, Dowrick C, et al. Fatigue Intervention by Nurses Evaluation - the FINE trial. A randomised controlled trial of nurse led self-help treatment for patients in primary care with chronic fatigue syndrome: study protocol. BMC Medicine 2006;4: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deale A, Chalder T, Marks I, Wessely S. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154: 408-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lloyd AR, Hickie I, Brockman A, et al. Immunologic and psychologic therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Med 1993;94: 197-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taylor RR, Braveman B, Hammel J. Developing and evaluating community-based services through participatory action research: two case examples. Am J Occup Ther 2004;58: 73-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cox DL. An Evaluation of an Occupational Therapy Inpatient Intervention for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome [Ph.D]. London: King's College London, 1999

- 64.Cox DL. Chronic fatigue syndrome: An evaluation of an occupational therapy inpatient intervention. Br J Occup Ther 2002;65: 461-68 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Friedberg F, Krupp LB. A comparison of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome and primary depression. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18(Suppl 1): S105-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peterson PK, Shepard J, Macres M, et al. A controlled trial of intravenous immunoglobulin G in chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med 1990;89: 554-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lloyd A, Hickie I, Wakefield D, Boughton C, Dwyer J. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med 1990;89: 561-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vollmer-Conna U, Hickie I, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin is ineffective in the treatment of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Am J Med 1997;103: 38-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andersson M, Bagby JR, Dyrehag LE, Gottfries CG. Effects of staphylococcus toxoid vaccine on pain and fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome. European Journal of Pain: EJP 1998;2: 133-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.See DM, Tilles JG. a-Interferon treatment of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Immunol Invest 1996;25: 153-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brook MG, Bannister BA, Weir WR. Interferon-alpha therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Infect Dis 1993;168: 791-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strayer DR, Carter WA, Brodsky I, et al. A controlled clinical trial with a specifically configured RNA drug, poly(I).poly(C12U), in chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 1994;18(Suppl 1): S88-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steinberg P, McNutt BE, Marshall P, et al. Double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of oral terfenadine in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1996;97: 119-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lerner AM, Zervos M, Chang CH, et al. A small, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the use of antiviral therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome [comment]. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32: 1657-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cleare AJ, Heap E, Malhi GS, Wessely S, O'Keane V, Miell J. Lowdose hydrocortisone in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomised crossover trial. Lancet 1999;353: 455-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McKenzie R, O'Fallon A, Dale J, et al. Low-dose hydrocortisone for treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280: 1061-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rowe PC, Calkins H, DeBusk K, et al. Fludrocortisone acetate to treat neurally mediated hypotension in chronic fatigue syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285: 52-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peterson PK, Pheley A, Schroeppel J, et al. A preliminary placebo-controlled crossover trial of fludrocortisone for chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med 1998;158: 908-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hickie IB, Wilson AJ, Wright J, Bennett BK, Wakefield D, Lloyd AR. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of moclobemide in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61: 643-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vercoulen J, Swanink CMA, Zitman FG, et al. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in chronic fatigue syndrome. Lancet 1996;347: 858-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Natelson BH, Cheu J, Hill N, et al. Single-blind, placebo phase-in trial of two escalating doses of selegiline in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuropsychobiology 1998;37: 150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Snorrason E, Geirsson A, Stefansson K. Trial of a selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, galanthamine hydrobromide, in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 1996;2: 35-54 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Forsyth LM, Preuss HG, MacDowell AL, Chiazze L Jr, Birkmayer GD, Bellanti JA. Therapeutic effects of oral NADH on the symptoms of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1999;82: 185-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Santaella ML, Font I, Disdier OM. Comparison of oral nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) versus conventional therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome. P R Health Sci J. 2004;23: 89-93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Morriss RK, Robson MJ, Deakin J. Neuropsychological performance and noradrenaline function in chronic fatigue syndrome under conditions of high arousal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163: 166-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Natelson BH, Cheu J, Pareja J, Ellis P, Policastro T, Findley TW. Randomized, double-blind, controlled placebo phase in trial of low dose phenelzine in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124: 226-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tiev KP, Cabane J, Imbert JC. Treatment of chronic postinfectious fatigue: randomized double-blind study of two doses of sulbutiamine (400-600 mg/day) versus placebo. Rev Med Interne 1999;20: 912-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Olson LG, Ambrogetti A, Sutherland DC. A pilot randomized controlled trial of dexamphetamine in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosomatics 2003;44: 38-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moorkens G, Wynants H, Abs R. Effect of growth hormone treatment in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: A preliminary study. Growth Horm IGF Res 1998;8: 131-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williams G, Waterhouse J, Mugarza J, Minors D, Hayden K. Therapy of circadian rhythm disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome: no symptomatic improvement with melatonin or phototherapy. Eur J Clin Invest 2002;32: 831-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Field TM, Sunshine W, Hernandez-Reif M, et al. Massage therapy effects on depression and somatic symptoms in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 1997;3: 43-51 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Perrin RN, Edwards J, Hartley P. An evaluation of the effectiveness of osteopathic treatment on symptoms associated with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis. A preliminary report. J Med Eng Technol 1998;22: 1-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brouwers FM, Van Der Werf S, Bleijenberg G, Van Der Zee L, Van Der Meer JW. The effect of a polynutrient supplement on fatigue and physical activity of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. QJM 2002;95: 677-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martin RWY, Ogston SA, Evans JR. Effects of vitamin and mineral supplementation on symptoms associated with chronic fatigue syndrome with Coxsackie B antibodies. J Nutr Med 1994;4: 11-23 [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stewart W, Rowse C. Supplements help ME says Kiwi study. J Altern Complement Med 1987;5: 19-20 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kaslow JE, Rucker L, Onishi R. Liver extract-folic acid-cyanocobalamin vs placebo for chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med 1989;149: 2501-3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ockerman PA. Antioxidant treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Clinical Practice of Alternative Medicine 2000;1: 88-91 [Google Scholar]

- 98.De Becker P, Nijs J, Van HE, McGregor N, De MK. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of acclydine in combination with amino acids in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. AHMF Proceedings, “Myalgic Encephalopathy/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome The Medical Practitioners' Challenge in 2001”. 2001

- 99.Rothschild PR, Huertas JG. Ambulatory naturopathic treatment of chronic fatigue immune deficiency syndrome (CFIDS) with RM-10 caplets. Progress in Nutrition 2002;4: 77-96 [Google Scholar]

- 100.Teitelbaum JE, Bird B, Greenfield RM, Weiss A, Muenz L, Gould L. Effective treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia - A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, intent-to-treat study. J Chronic Fatigue Syndr 2001;8: 3-28 [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marlin RG, Anchel H, Gibson JC, Goldberg WM, Swinton M. An evaluation of multidisciplinary intervention for chronic fatigue syndrome with long-term follow-up, and a comparison with untreated controls. Am J Med 1998;105: 110S-14S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goudsmit E. Learning to Cope with Post-Infectious Fatigue Syndrome, a Follow-up Study. Brunel, 1996

- 103.Schlaes J, Jason L. A buddy/mentor program for PWCs. CFIDS Chronicle 1996: 21-5

- 104.Söderberg S, Evengård B. Short-term group therapy for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychother Psychosom 2001;70: 108-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]