Abstract

Background

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant disease characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas in many internal organs. Mutations in either one of 2 genes, TSC1 and TSC2, have been attributed to the development of TSC. More than two-thirds of TSC patients are sporadic cases, and a wide variety of mutations in the coding region of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes have been reported.

Methods

Mutational analysis of TSC1 and TSC2 genes was performed in 84 Taiwanese TSC families using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) and direct sequencing.

Results

Mutations were identified in a total of 64 (76 %) cases, including 9 TSC1 mutations (7 sporadic and 2 familial cases) and 55 TSC2 mutations (47 sporadic and 8 familial cases). Thirty-one of the 64 mutations found have not been described previously. The phenotype association is consistent with findings from other large studies, showing that disease resulting from mutations to TSC1 is less severe than disease due to TSC2 mutation.

Conclusion

This study provides a representative picture of the distribution of mutations of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in clinically ascertained TSC cases in the Taiwanese population. Although nearly half of the mutations identified were novel, the kinds and distribution of mutation were not different in this population compared to that seen in larger European and American studies.

Background

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant disorder having an incidence of 1 in 6,000 to 1 in 10,000 live births [1]. The severity of TSC and its impact on the quality of life are extremely variable among patients [2]. Common clinical manifestations of this disease include intellectual handicap, autistic disorders, and epilepsy due to the frequent, widespread occurrence of cortical tubers, which are focal disruptions of the cortical architecture due to undifferentiated giant cells. Hamartomas are also found in multiple other organ systems, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, and skin [3].

Patients often seek medical attention for dermal lesions or frequent seizures. The clinical diagnostic guidelines on TSC were prepared based on clinical features, radiographic findings, and histopathological findings [3]. Accurate clinical diagnoses are relatively easy in patients with classic multisystem involvement, but are often difficult due to the diversity of clinical findings in TSC patients.

The genetic basis of TSC has been determined to be due to mutation in either one of two unlinked genes, TSC1 and TSC2 [4]. The human TSC1 gene on chromosome 9q34 consists of 23 exons giving an 8.6-kb mRNA transcript, which has a coding region of 3.5-kb and encodes a 130-kDa protein spanning 1164 amino acids [5]. The TSC2 gene, which is located on chromosome 16p13.3, contains 41 exons and encodes a 200-kDa protein with 1807 amino acid [4,6]. Both TSC1 and TSC2 are tumor suppressor genes and their protein products, hamartin and tuberin, respectively, form a complex that regulates the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3-kinase)/AKT pathway to control cellular proliferation, adhesion, growth, differentiation or migration [7,8]. Furthermore, both genes play a role in cortical differentiation and growth control.

The mutation spectra of the TSC genes are very heterogeneous and no hotspots for mutations have been reported. There are many mutations in each gene that are seen recurrently, but no single mutation accounts for more than about 1% of all TSC patients. TSC2 mutations are about five times more common than TSC1 mutations [9] and new mutations are typically found in the two-thirds of TSC cases that are sporadic [10]. Despite complete penetrance of the disease in TSC patients, phenotypic variability can make the determination of disease status difficult among family members of affected individuals.

In this study, we analyzed both TSC1 and TSC2 genes in 84 independent Taiwanese TSC probands for whom detailed information on clinical manifestations and phenotype were available. Furthermore, we also assessed the mutational distribution and possible genotype-phenotype correlations between and within the two genes.

Methods

Patient Population

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Division of Obstetrics and Gynecology, National Taiwan University Hospital. Eighty-four unrelated patients with confirmed clinical diagnoses of TSC and their family members were tested for mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 genes.

The general clinical features of TSC patients were determined by clinicians in accordance with the TSC diagnosis criteria set forth by the Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Conference [3]. All patients' symptoms were investigated by a person blind to mutational status. High-resolution brain magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) was performed on most patients.

The extent of facial angiofibroma or forehead plaques, non-traumatic ungal or periungal fibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, multiple retinal nodular hamartomas, cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, cardiac rhabdomyomas, lymphangiomyomatoses, renal angiomyolipomas and confetti-like lesions were all assessed. Moreover, most patients' medical histories of mental development were assessed by a certified psychologist.

Sample Preparation

After genetic counseling and obtaining informed consent, 5–10 mL of peripheral blood were collected from the participants. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral whole blood using the Puregene DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Mutational Analysis of TSC Genes

PCR primers and running conditions for each exon were available from previous studies [11-13]. The PCR reaction was run on each exon with a total sample volume of 25 μL containing 100 ng of genomic DNA, 0.12 μM of each respective primer, 100 μM dNTPs, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 units of AmpliTaq Gold enzyme (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplification was performed in a multiblock system thermocycler (ThermoHybaid, Ashford, UK). The PCR amplification started with a denaturing step at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at melting temperature (Tm) for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 45 seconds, and ends with a final extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes.

The screening of mutations was performed using the Transgenomic Wave Nucleic Acid Fragment Analysis System (Transgenomic Inc, San Jose, CA) with a C18 reversed-phase column containing 2-μm nonporous poly (styrene/divinylbenzene) particles (DNASep Column, Transgenomic Inc). PCR products were analyzed using linear acetonitrile gradients and triethylammonium acetate acting as mobile phases with the provision of buffer A (0.1 M TEAA) and buffer B (0.1 M TEAA with 25% acetonitrile) (WAVE Optimized, Transgenomic Inc). Heteroduplex analyses were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol and of previous studies [14,15].

Statistical method

The χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used to examine the differences in clinical manifestations, phenotypes, and mutation distributions in independent Taiwanese probands between patients with TSC1 and TSC2 genes.

Direct Sequence Analysis

PCR products were purified by solid-phase extraction and bidirectionally sequenced using Applied Biosystems' Taq DyeDeoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing reactions were separated on a PE Biosystems 373A/3100 sequencer.

Results and Discussion

Identification and Characterization of Mutations

In the current study, we performed mutational analysis on the coding exons and the exon/intron junctions of both TSC1 and TSC2 in a total of 84 individuals with TSC and their family members. The determination of mutation vs. polymorphism was done by: 1) checking the mutation tables at the Chromium site (http://chromium.liacs.nl/); 2) comparison of findings to those of 100 healthy Taiwanese controls; and 3) checking the families similarly.

Nine mutations were identified in the TSC1 gene while 55 were identified in the TSC2 gene. Mutations in the TSC1 gene included five nonsense mutations with early termination codons and four insertions/deletions which caused frameshifts and resulted in premature truncation of the protein. Three of these mutations were novel, while six were previously reported (Table 1).

Table 1.

Status of TSC1 mutations in Taiwanese patients with TSC

| No. | Gene | Exon | Nucleotide change | Codon change | Mutation type | Inheritance | Reported | Reference |

| 62 | TSC1 | 7 | c.602_604del CCT | In-frame deletion | S | N | This study | |

| 61 | TSC1 | 15 | c.1525C>T | p.R509X | Nonsense | F | R | [5] |

| 72 | TSC1 | 15 | c.1791_1792dupAA | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 2 | TSC1 | 15 | c.1884_1887delAAAG | Frameshift | F | R | [5] | |

| 36 | TSC1 | 15 | c.1959dupA | Frameshift | S | R | LOVD* | |

| 54 | TSC1 | 17 | c.2074C>T | p.R692X | Nonsense | S | R | [5] |

| 31 | TSC1 | 18 | c.2283C>A | p.Y761X | Nonsense | S | R | [24] |

| 3 | TSC1 | 18 | c.2332C>T | p.Q778X | Nonsense | S | N | This study |

| 41 | TSC1 | 18 | c.2356C>T | p.R786X | Nonsense | S | R | [5] |

| Total: 9, F:2, S:7, N:3, R:6 MM:0, NM:5, FM:4, SM:0. | ||||||||

F: familial case, S:sporadic case.

N: non-reported, R: reported.

MM: missense mutations, NM: nonsense mutations, FM: frameshift/in-frame mutations, SM: splicing site mutations.

* The the Leiden Open (source) Variation Database which was available at http://chromium.liacs.nl/lovd/.

The 55 mutations in the TSC2 gene included 12 missense, 15 nonsense, 21 frameshifts due to insertions and deletions and 7 putative splice-site mutations. Twenty-seven of these mutations were previously reported while 28 were novel (Table 2). Of the familial TSC2 missense mutations, A1141T and R1793Q may be rare polymorphic variants co-segregating with TSC. There was no direct evidence that these familial TSC2 missense mutational changes were pathogenic.

Table 2.

Status of TSC2 mutations in Taiwanese patients with TSC

| No. | Gene | Exon | Nucleotide change | Codon change | Mutation type | Inheritance | Reported | Reference |

| 21 | TSC2 | 1 | c.109dupG | Frameshift | F | N | This study | |

| 30 | TSC2 | 1 | c.133_136delCTGA | Frameshift | S | R | DK* | |

| 35 | TSC2 | 3 | c.268C>T | p.Q90X | Nonsense | S | R | [25] |

| 47 | TSC2 | 6 | c.632delC | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 8 | TSC2 | intron 8 | c.848+3delG | Splicing | S | N | This study | |

| 37 | TSC2 | 9 | c.856A>G | p.M286V | Missense | F | R | [10] |

| 78 | TSC2 | 10 | c.1060C>T | p.Q354X | Nonsense | S | N | This study |

| 75 | TSC2 | 10 | c.1117C>T | p.Q373X | Nonsense | S | R | DK* |

| 48 | TSC2 | 11 | c.1226_1230delAACTG | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 12 | TSC2 | 12 | c.1336C>T | p.Q446X | Nonsense | S | R | [25] |

| 20 | TSC2 | 14 | c.1513C>T | p.R505X | Nonsense | S | R | [10] |

| 57 | TSC2 | 14 | c.1513C>T | p.R505X | Nonsense | S | R | [10] |

| 65 | TSC2 | intron 14 | c.1599+2T>C | Splicing | S | N | This study | |

| 76 | TSC2 | 16 | c.1794C>G | p.Y598X | Nonsense | S | R | [10] |

| 29 | TSC2 | 16 | c.1832G>A | R611Q | Missense | S | R | [10] |

| 59 | TSC2 | intron 16 | c.1840-2A>T | Spilicing | S | N | This study | |

| 82 | TSC2 | 17 | c.1939G>A | p.D647N | Missense | S | R | [26] |

| 7 | TSC2 | 18 | c.2086T>C | p.C696R | Missense | S | R | [27] |

| 53 | TSC2 | 19 | c.2103_2105dupTGA | In-frame insertion | S | N | This study | |

| 5 | TSC2 | 19 | c.2210T>C | p.L737P | Missense | S | N | This study |

| 23 | TSC2 | 20 | c.2251C>T | p.R751X | Nonsense | S | R | [10] |

| 70 | TSC2 | 20 | c.2251C>T | p.R751X | Nonsense | S | R | [10] |

| 39 | TSC2 | 21 | c.2404dupA | Frameshift | F | N | This study | |

| 32 | TSC2 | 21 | c.2461A>T | p.K821X | Nonsense | S | N | This study |

| 11 | TSC2 | 21 | c.2538delC | Frameshift | F | N | This study | |

| 67 | TSC2 | intron 21 | c.2546-2A>T | Splicing | S | N | This study | |

| 73 | TSC2 | intron 22 | c.2639+1G>C | Splicing | S | R | [9] | |

| 22 | TSC2 | 23 | c.2641delT | Frameshift | F | N | This study | |

| 27 | TSC2 | 24 | c.2824G>T | p.Q942X | Nonsense | S | N | This study |

| 64 | TSC2 | 26 | c.2974C>T | p.Q992X | Nonsense | S | R | [28] |

| 80 | TSC2 | 26 | c.3076dupT | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 33 | TSC2 | 28 | c.3389delC | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 19 | TSC2 | 29 | c.3412C>T | p.R1138X | Nonsense | S | R | [9] |

| 42 | TSC2 | 29 | c.3421G>A | p.A1141T | Missense | F | N | This study |

| 13 | TSC2 | 30 | c.3693_3696delGTCT | Frameshift | S | R | DK* | |

| 51 | TSC2 | 30 | c.3696dupT | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 9 | TSC2 | 33 | c.4175_4176delAG | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 26 | TSC2 | 33 | c.4440dupA | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 77 | TSC2 | 34 | c.4541_4544delCAAA | Frameshift | S | R | [12] | |

| 18 | TSC2 | 35 | c.4603_4605delGAC | In-frame deletion | S | N | This study | |

| 34 | TSC2 | 35 | c.4603G>T | p.D1535Y | Missense | S | N | This study |

| 83 | TSC2 | 36 | c.4830G>A | p.W1610X | Nonsense | S | R | DK* |

| 28 | TSC2 | 36 | c.4846C>T | p.Q1616X | Nonsense | S | N | This study |

| 16 | TSC2 | 37 | c.4909_4910delAA | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 81 | TSC2 | 38 | c.5032dupT | Frameshift | S | N | This study | |

| 60 | TSC2 | 39 | c.5150T>C | p.L1717P | Missense | S | R | [29] |

| 55 | TSC2 | intron 39 | c.5160+3G>C | Splicing | S | N | This study | |

| 43 | TSC2 | intron 39 | c.5160+4A>G | Splicing | S | R | [29] | |

| 4 | TSC2 | 40 | c.5227C>T | p.R1743W | Missense | S | R | DK * |

| 50 | TSC2 | 40 | c.5227C>T | p.R1743W | Missense | S | R | DK* |

| 56 | TSC2 | 40 | c.5228G>A | p.R1743Q | Missense | F | R | [30] |

| 10 | TSC2 | 40 | c.5238_5255del18 | Frameshift | S | R | [31] | |

| 25 | TSC2 | 40 | c.5238_5255del18 | Frameshift | S | R | [31] | |

| 6 | TSC2 | 40 | c.5252_5259+19del27 | Frameshift | S | R | [9] | |

| 15 | TSC2 | 41 | c.5378G>A | p.R1793Q | Missense | F | N | This study |

| Total: 55, F:8, S:47, N:28, R:27 MM:12, NM:15, FM:21, SM:7. | ||||||||

F: familial case, S:sporadic case.

N: non-reported, R: reported.

MM: missense mutations, NM: nonsense mutations, FM: frameshift/in-frame mutations, SM: splicing site mutations.

* The database of Dr David Kwiatkowski which was available at http://tsc-project.partners.org/.

For both genes, sequence variants that were possible mutations were tested in all other family members, including the parents and both the affected and the unaffected family members. In total, 31 of the 64 mutations (48%) had not been reported elsewhere. Moreover, no mutational hotspots were identified in either gene, with only four different mutations being found twice in TSC2.

Compared with those of European and American counterparts [9,10,16], the distribution of the TSC1 and TSC2 mutations among Taiwanese population is similar. Therefore, the spectrum of mutations seen among the Taiwanese is no different in comparison to those already reported thus far for these two genes, based on the genetic analyses of European and American TSC patients using the Fisher exact test (P = 0.85, 0.46, and 0.14, respectively).

Identification and Characterization of Polymorphism

In order to identify whether the observed changes were mutations or polymorphisms, samples from 100 normal individuals serving as controls were analyzed. Changes that were not found in more than 200 control alleles were considered pathogenic. Therefore, unique or less frequent changes such as missense and splicing site mutations (Table 2) were considered likely pathogenic mutations. The nonpathogenic TSC1 and TSC2 mutations identified in the Taiwanese TSC patients are described in Table 3. We identified nine nonpathogenic polymorphisms in the TSC1 gene and 12 in the TSC2 gene. The nonpathogenic sequence variants were identified in both the TSC patients and the normal controls. Fourteen of these polymorphisms had not been reported previously (4 at the TSC1 locus and 10 at the TSC2 locus) that included one missense variant within the TSC1 coding region.

Table 3.

Polymorphisms identified for TSC1 and TSC2 in Taiwanese TSC population.

| TSC1 | ||||||

| Exon | Nucleotide change | Codon change | Polymorphism type | Frequency | Reported | Reference |

| Intron 3 | c.106+15 | Intron | 13 (16 %) | N | This study | |

| 10 | c.965 T>C | p.M322T | Missense | 9 (11%) | R | [24] |

| Intron 11 | c.1142-33 A>G | Intron | 9 (11%) | R | LOVDa | |

| Intron 12 | c.1264-12 T>C | Intron | 3 (4 %) | N | This study | |

| Intron 14 | c.1437-37 C>T | Intron | 9 (11%) | R | LOVDa | |

| 15 | c.1726 T>C | p.L576L | Silent | 11 (13 %) | N | This study |

| 15 | c.1960 C>G | p.Q654E | Missense | 3 (4 %) | N | This study |

| Intron 18 | c.2392-35 T>C | Intron | 9 (11%) | R | [24] | |

| 22 | c.2829 C>T | p.A943A | Silent | 3 (4 %) | R | [24] |

| TSC2 | ||||||

| Exon | Nucleotide change | Codon change | Polymorphism type | Frequency | Reported | Reference |

| 14 | c.1593 C>T | p.I531I | Silent | 3 (4 %) | R | [26] |

| Intron 15 | c.1717-30 G>A | Intron | 2 (2 %) | N | This study | |

| Intron 15 | c.1717-27 G>A | Intron | 1 (1 %) | N | This study | |

| Intron 21 | c.2545+45 T>A | Intron | 11 (13 %) | N | This study | |

| 23 | c.2652 C>T | p.Y884Y | Silent | 1 (1 %) | N | This study |

| 26 | c.3126 G>T | p.P1042P | Silent | 1 (1 %) | R | DKb |

| Intron 27 | c.3285-19 C>T | Intron | 1 (1 %) | N | This study | |

| 29 | c.3475 C>T | p.R1159R | Silent | 1 (1 %) | N | This study |

| 33 | c.4047 G>A | p.A1349A | Silent | 2 (2 %) | N | This study |

| Intron 33 | c.4493+18 G>A | Intron | 1 (1 %) | N | This study | |

| Intron 38 | c.5069-21 G>A | Intron | 1 (1 %) | N | This study | |

| Intron 39 | c.5161-9 C>T | Intron | 7 (8 %) | N | This study | |

* Frequence means the number of cases in 84 Taiwanese TSC patients.

a The the Leiden Open (source) Variation Database which was available at http://chromium.liacs.nl/lovd/.

b The database of Dr David Kwiatkowski which was available at http://tsc-project.partners.org/.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlation: Familial or Sporadic TSC mutations

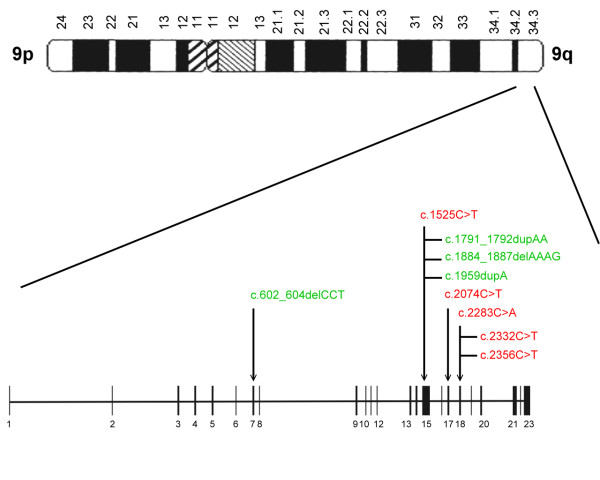

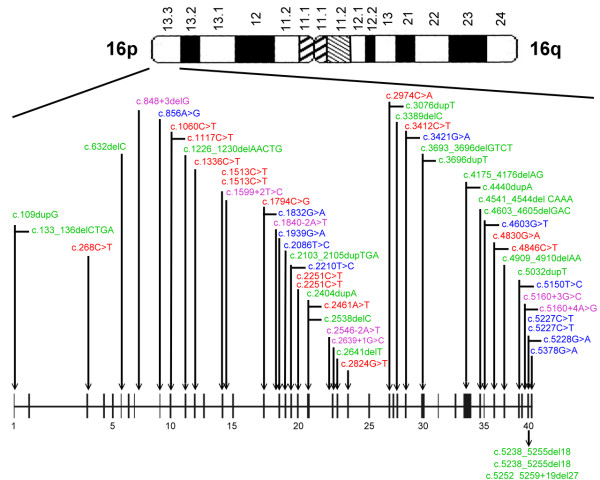

Mutations were identified and located in exons of both TSC1 and TSC2 genes (see Figure 1 and 2). Of the 64 mutations found, nine and 55 were associated with TSC1 (14%) and TSC2 (86%), respectively, as shown in Table 4. Of the 10 familial cases, 2 (20%) and 8 (80%) were TSC1and TSC2 mutations, respectively. Among the 54 sporadic cases, 7 TSC1 (13%) and 47 TSC2 (87%) mutations were found. Accordingly, there was no significant difference between sporadic and familial TSC cases with respect to the frequency of TSC1 vs TSC2 mutation (P = 0.62).

Figure 1.

Diagram depicting the locations of mutations in the TSC1 gene. Nonsense (red), missense (blue), frameshift/in-frame (green) and splicing site (purple) mutations were identified.

Figure 2.

Diagram depicting the locations of mutations in the TSC2 gene. Nonsense (red), missense (blue), frameshift/in-frame (green) and splicing site (purple) mutations were identified.

Table 4.

Distribution of TSC1 and TSC2 mutations.

| N | MM | NM | FM | SM | Total | |

| TSC1 mutaions | ||||||

| Familial | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 (3 %) |

| Sporadic | 7 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 (11 %) |

| Total | 9 | 0 (0 %) | 5 (8 %) | 4 (6 %) | 0 (0 %) | 9 (14 %) |

| TSC2 mutations | ||||||

| Familial | 8 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 8 (13 %) |

| Sporadic | 47 | 8 | 15 | 17 | 7 | 47 (73 %) |

| Total | 55 | 12 (19 %) | 15 (23 %) | 21 (33 %) | 7 (11 %) | 55 (86 %) |

N: screening numbers.

MM: missense mutations.

NM: nonsense mutations.

FM: frameshift/in-frame mutations.

SM: splicing site mutations.

Genotype-Phenotype Correlation: Clinical Manifestations

The clinical characteristics associated with each mutation in the proband are shown in Tables 5 (eight TSC1 mutations) and Table 6 (43 TSC2 mutations). Most patients with TSC1 and TSC2 mutations had seizures, brain lesions (subependymal nodules and/or cortical tubers detected by MRI), and dermal manifestations. Our criteria for intellectual disability included any degree of mental retardation and learning disorder. The incidence of intellectual disability appeared lower in patients with TSC1 mutations (3/8 = 38%) compared to that of patients with TSC2 mutations (27/43 = 63%). However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.25), but this would be expected because of such small sample sizes. Similarly, the incidence of mental retardation in patients with TSC1 mutations (1/8 = 13%) appeared to be less than that of patients with TSC2 mutations (17/43 = 40%), but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.23). Similarly, the frequencies of renal findings, cortical tubers, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, liver tumors, cardiac tumors, or skin manifestations, including hypomelanotic macules, facial angiofibromas, shagreen patches, and ungual fibromas did not significantly differ between the patients with TSC1 and TSC2 mutations. However, all of these comparisons are under-powered due to the relatively small number of patients with TSC1 mutations that were studied. For nearly all of the clinical features studied, the frequencies were less for those bearing TSC1 mutations than for those bearing TSC2 mutations. This is consistent with findings from other large studies, showing that TSC1 disease is less severe than TSC2 disease [9,10,16].

Table 5.

Clinical data of patients with TSC1 mutations

| Family no. | Familial/Sporadic | Mutation type | Sex | Onset age of seizure | Intellectual performance | Brain tubers | Renal tumors | Hepatic tumors | Cardiac rhabdomyoma | Hypomelanotic macules | Facial angiofibroma | Shagreen patch | Ungual fibroma |

| 2 | F | FS | F | 2 y | N | + | 0 | NA | NA | 0 | + | 0 | + |

| 3 | S | NM | M | 8 y 3 m | N | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 41 | S | NM | F | 1 y | N | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 31 | S | NM | F | 6 m | LD | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 36 | S | FS | M | 2 y | N | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 61 | F | NM | M | 3 y 6 m | LD | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 62 | S | FS | M | 1 m | LD | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + |

| 72 | S | FS | M | 3 y | N | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 |

N: normal or no seizure, LD: learning disorder, MR: metal retardation, NA: not available.

Table 6.

Clinical data of patients with TSC2 mutations

| Family no. | Familial/Sporadic | Mutation type | Sex | Onset age of seizure | Intellectual performance | Brain tubers | Renal tumors | Hepatic tumors | Cardiac rhabdomyoma | Hypomelanotic macules | Facial angiofibroma | Shagreen patch | Ungual fibroma |

| 4 | S | MM | M | 10 m | N | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 5 | S | MM | F | 1 y | N | + | NA | NA | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | S | FS | M | 1 m | LD | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | S | MM | M | 6 m | MR | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | S | S | F | 3 m | LD | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 9 | S | FS | M | 5 y | LD | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 10 | S | FS | F | 6 m | LD | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | F | FS | F | 4 m | LD | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| 12 | S | NM | M | 10 m | N | + | + | 0 | NA | + | + | + | 0 |

| 13 | S | FS | F | 4 m | MR | + | NA | NA | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | F | MM | F | 7 m | MR | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | S | FS | M | 1 y | N | + | + | 3 | NA | + | + | + | + |

| 18 | S | FS | F | 5 m | LD | + | NA | NA | NA | + | + | + | 0 |

| 19 | S | NM | M | 3 m | MR | + | + | 0 | NA | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | S | NM | M | 1 y 6 m | N | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | F | FS | F | 9 y | N | + | + | 1 | 0 | + | + | + | + |

| 22 | F | FS | M | 1 y | LD | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | + | + | 0 |

| 23 | S | NM | F | 7 m | MR | + | NA | NA | NA | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | S | FS | M | 6 m | LD | + | 0 | NA | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 26 | S | FS | F | 8 m | LD | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 27 | S | NM | M | 1 y | MR | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | S | NM | M | 3 m | LD | + | NA | NA | NA | + | + | + | 0 |

| 29 | S | MM | F | 6 m | MR | + | 0 | NA | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| 30 | S | FS | F | 1 y | MR | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 32 | S | NM | M | 3 m | N | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 33 | S | FS | F | 1 m | N | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + |

| 34 | S | MM | F | 7 y | N | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| 35 | S | NM | M | 1 y | MR | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| 37 | F | MM | M | 9 m | MR | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 |

| 39 | F | FS | F | 3 m | MR | + | NA | NA | NA | + | + | + | 0 |

| 42 | F | MM | M | 7 y | N | 0 | + | + | NA | + | + | + | + |

| 47 | S | FS | F | 2 m | N | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 48 | S | FS | F | 3 m | MR | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 50 | S | MM | M | 3 m | MR | + | NA | NA | NA | + | + | + | 0 |

| 53 | S | FS | M | 3 y | MR | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 56 | F | MM | F | 2 y | N | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + |

| 57 | S | NM | F | 6 m | MR | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| 59 | S | S | F | 1 m | MR | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 64 | S | NM | M | 2 m | N | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 67 | S | S | F | 3 m | MR | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 73 | S | S | F | 21 y | N | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + |

| 75 | S | NM | F | 1 y | N | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 82 | S | MM | M | 1 m | N | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

N: normal or no seizure, LD: learning disorder, MR: metal retardation, NA: not available.

Conclusion

This study is the first analysis of TSC1 and TSC2 genes in the Taiwanese population. We identified 64 mutations among a total of 84 patients (76%); 9 were TSC1 mutations (14%) and 55 were TSC2 mutations (86%). These numbers are similar to other studies with larger cohorts [9,10,16-18] and would be expected if the germ line mutation rate at the TSC2 locus were higher than that at the TSC1 locus. The failure to detect mutations in the remaining 24% of the patients may be due to a combination of lack of screening for large genomic deletion and rearrangement mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2. The occurrence of mosaic mutations [19,20] in some of these patients that may be difficult to detect. Another reason is mutation detection failure.

According to previous reports, somatic and general mosaicism are seen in 6%-10% of all TSC patients [20,21]. In addition, large deletions have been identified in about 2%-4% of TSC2 mutations [6] and less commonly in the TSC1 gene [22,23]. Thus, both of these situations likely contributed to patients in which mutations were not identified.

In summary, sixty-four different mutations were identified and characterized for the Taiwanese population. Of those, 31 were not previously described. The diverse mutation spectrum of TSC was also seen in different families and different populations.

Abbreviations

DHPLC: Denaturing high performance liquid chromatography

TSC: Tuberous sclerosis complex

CT: Computed tomography

MRI: Magnetic-resonance imaging

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

Tm: Melting temperature

Competing interests

We received financial support in the form of a grant from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 92-2314-B-002-319). We have no other competing interests to declare.

Authors' contributions

CCH and YNS performed the molecular genetics studies and drafted the manuscript. SCC participated in the molecular genetics studies. HHL and CCC performed the clinical characterization of the patients. PCC and CJH performed the statistical analyses. CPC, WTL and WLL participated in the design of the study. CNL conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully extend their gratitude to the families and patients affected by TSC for their participation and cooperation in this study. We thank Prof. David Kwiatkowski, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School for deeply review and rewrite the manuscript. We thank Dr. Fon-Jou Hsieh for his expertise and assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 92-2314-B-002-319).

Contributor Information

Chia-Cheng Hung, Email: r91548020@ntu.edu.tw.

Yi-Ning Su, Email: ynsu@ntumc.org.

Shu-Chin Chien, Email: chien-sc@yahoo.com.tw.

Horng-Huei Liou, Email: liou@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw.

Chih-Chuan Chen, Email: chihch@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw.

Pau-Chung Chen, Email: pchen@ntu.edu.tw.

Chia-Jung Hsieh, Email: r92841014@ntu.edu.tw.

Chih-Ping Chen, Email: cpc_mmh@yahoo.com.

Wang-Tso Lee, Email: leeped@hotmail.com.

Win-Li Lin, Email: winli@ntu.edu.tw.

Chien-Nan Lee, Email: leecn@ntumc.org.

References

- Osborne JP, Fryer A, Webb D. Epidemiology of tuberous sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;615:125–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MR SJRHWV. Tuberous sclerosis complex. 3rd edn New York: Oxford University Press. 1999.

- Roach ES, Gomez MR, Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference: revised clinical diagnostic criteria. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:624–628. doi: 10.1177/088307389801301206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povey S, Burley MW, Attwood J, Benham F, Hunt D, Jeremiah SJ, Franklin D, Gillett G, Malas S, Robson EB, et al. Two loci for tuberous sclerosis: one on 9q34 and one on 16p13. Ann Hum Genet. 1994;58 (Pt 2):107–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1994.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, Nellist M, Janssen B, Verhoef S, Lindhout D, van den Ouweland A, Halley D, Young J, Burley M, Jeremiah S, Woodward K, Nahmias J, Fox M, Ekong R, Osborne J, Wolfe J, Povey S, Snell RG, Cheadle JP, Jones AC, Tachataki M, Ravine D, Sampson JR, Reeve MP, Richardson P, Wilmer F, Munro C, Hawkins TL, Sepp T, Ali JB, Ward S, Green AJ, Yates JR, Kwiatkowska J, Henske EP, Short MP, Haines JH, Jozwiak S, Kwiatkowski DJ. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science. 1997;277:805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. The European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. Cell. 1993;75:1305–1315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Tuberous sclerosis complex: linking growth and energy signaling pathways with human disease. Oncogene. 2005;24:7475–7481. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Manning BD. Tuberous sclerosis: a GAP at the crossroads of multiple signaling pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14 Spec No. 2:R251–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabora SL, Jozwiak S, Franz DN, Roberts PS, Nieto A, Chung J, Choy YS, Reeve MP, Thiele E, Egelhoff JC, Kasprzyk-Obara J, Domanska-Pakiela D, Kwiatkowski DJ. Mutational analysis in a cohort of 224 tuberous sclerosis patients indicates increased severity of TSC2, compared with TSC1, disease in multiple organs. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:64–80. doi: 10.1086/316951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AC, Shyamsundar MM, Thomas MW, Maynard J, Idziaszczyk S, Tomkins S, Sampson JR, Cheadle JP. Comprehensive mutation analysis of TSC1 and TSC2-and phenotypic correlations in 150 families with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1305–1315. doi: 10.1086/302381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AC, Daniells CE, Snell RG, Tachataki M, Idziaszczyk SA, Krawczak M, Sampson JR, Cheadle JP. Molecular genetic and phenotypic analysis reveals differences between TSC1 and TSC2 associated familial and sporadic tuberous sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2155–2161. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwar MM, Cheadle JP, Jones AC, Myring J, Fryer AE, Harris PC, Sampson JR. The GAP-related domain of tuberin, the product of the TSC2 gene, is a target for missense mutations in tuberous sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1991–1996. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwar MM, Sandford R, Nellist M, Cheadle JP, Sgotto B, Vaudin M, Sampson JR. Comparative analysis and genomic structure of the tuberous sclerosis 2 (TSC2) gene in human and pufferfish. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:131–137. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YN, Lee CN, Hung CC, Chen CA, Cheng WF, Tsao PN, Yu CL, Hsieh FJ. Rapid detection of beta-globin gene (HBB) mutations coupling heteroduplex and primer-extension analysis by DHPLC. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:326–336. doi: 10.1002/humu.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao W, Oefner PJ. Denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography: A review. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:439–474. doi: 10.1002/humu.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancak O, Nellist M, Goedbloed M, Elfferich P, Wouters C, Maat-Kievit A, Zonnenberg B, Verhoef S, Halley D, van den Ouweland A. Mutational analysis of the TSC1 and TSC2 genes in a diagnostic setting: genotype--phenotype correlations and comparison of diagnostic DNA techniques in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13:731–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JC, Thomas HV, Murphy KC, Sampson JR. Genotype and psychological phenotype in tuberous sclerosis. J Med Genet. 2004;41:203–207. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.012757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AC, Sampson JR, Hoogendoorn B, Cohen D, Cheadle JP. Application and evaluation of denaturing HPLC for molecular genetic analysis in tuberous sclerosis. Hum Genet. 2000;106:663–668. doi: 10.1007/s004390050040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska J, Wigowska-Sowinska J, Napierala D, Slomski R, Kwiatkowski DJ. Mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis as a potential cause of the failure of molecular diagnosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:703–707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson JR, Maheshwar MM, Aspinwall R, Thompson P, Cheadle JP, Ravine D, Roy S, Haan E, Bernstein J, Harris PC. Renal cystic disease in tuberous sclerosis: role of the polycystic kidney disease 1 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:843–851. doi: 10.1086/514888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef S, Bakker L, Tempelaars AM, Hesseling-Janssen AL, Mazurczak T, Jozwiak S, Fois A, Bartalini G, Zonnenberg BA, van Essen AJ, Lindhout D, Halley DJ, van den Ouweland AM. High rate of mosaicism in tuberous sclerosis complex. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1632–1637. doi: 10.1086/302412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellist M, Sancak O, Goedbloed MA, van Veghel-Plandsoen M, Maat-Kievit A, Lindhout D, Eussen BH, de Klein A, Halley DJ, van den Ouweland AM. Large deletion at the TSC1 locus in a family with tuberous sclerosis complex. Genet Test. 2005;9:226–230. doi: 10.1089/gte.2005.9.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longa L, Saluto A, Brusco A, Polidoro S, Padovan S, Allavena A, Carbonara C, Grosso E, Migone N. TSC1 and TSC2 deletions differ in size, preference for recombinatorial sequences, and location within the gene. Hum Genet. 2001;108:156–166. doi: 10.1007/s004390100460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabora SL, Sigalas I, Hall F, Eng C, Vijg J, Kwiatkowski DJ. Comprehensive mutation analysis of TSC1 using two-dimensional DNA electrophoresis with DGGE. Ann Hum Genet. 1998;62 ( Pt 6):491–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1998.6260491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy YS, Dabora SL, Hall F, Ramesh V, Niida Y, Franz D, Kasprzyk-Obara J, Reeve MP, Kwiatkowski DJ. Superiority of denaturing high performance liquid chromatography over single-stranded conformation and conformation-sensitive gel electrophoresis for mutation detection in TSC2. Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63 ( Pt 5):383–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1999.6350383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Nanba E, Yamamoto T, Ninomiya H, Ohno K, Mizuguchi M, Takeshita K. Mutational analysis of TSC1 and TSC2 genes in Japanese patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. J Hum Genet. 1999;44:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s100380050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PS, Ramesh V, Dabora S, Kwiatkowski DJ. A 34 bp deletion within TSC2 is a rare polymorphism, not a pathogenic mutation. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:495–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp RL, Banwell A, McNamara P, Jacobsen M, Higgins E, Northrup H, Short P, Sims K, Ozelius L, Ramesh V. Exon scanning of the entire TSC2 gene for germline mutations in 40 unrelated patients with tuberous sclerosis. Hum Mutat. 1998;12:408–416. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:6<408::AID-HUMU7>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Su YN, Hung CC, Lee CN, Hsieh FJ, Chang TY, Chen MR, Wang W. Molecular genetic analysis of the TSC genes in two families with prenatally diagnosed rhabdomyomas. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:176–178. doi: 10.1002/pd.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa T, Wakisaka A, Daido S, Takao S, Tamiya T, Date I, Koizumi S, Niida Y. A case of solitary subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: two somatic hits of TSC2 in the tumor, without evidence of somatic mosaicism. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:544–549. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60586-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niida Y, Lawrence-Smith N, Banwell A, Hammer E, Lewis J, Beauchamp RL, Sims K, Ramesh V, Ozelius L. Analysis of both TSC1 and TSC2 for germline mutations in 126 unrelated patients with tuberous sclerosis. Hum Mutat. 1999;14:412–422. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(199911)14:5<412::AID-HUMU7>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]