Abstract

The objective of the study was to develop a culturally relevant video and a pamphlet for use as a cervical cancer screening educational intervention among North-American Chinese women. The project conducted 87 qualitative interviews and nine focus groups to develop a culturally tailored intervention to improve Pap testing rates. The intervention consisted of an educational/motivational video, a pamphlet, and home visits. Less acculturated Chinese women draw on a rich tradition of herbal knowledge and folk practices historically based on Chinese medical theory, now mixed with new information from the media and popular culture. The video, the pamphlet, and the outreach workers knowledge base were designed using these results and combined with biomedical information to address potential obstacles to Pap testing. Culturally relevant information for reproductive health promotion was easily retrieved through qualitative interviews and used to create educational materials modeling the integration of Pap testing into Chinese women’s health practices.

Keywords: Pap testing, cervical cancer, cross-cultural medicine, Chinese, health education

INTRODUCTION

The United States (U.S.) 2000 Census counted ethnic Chinese at 2.4 million, and the Chinese are now the largest Asian subgroup in both Canada and the United States (1, 2). The Chinese are also the oldest Asian community in the Americas, arriving in the mid-1800s. There have been at least three waves of Chinese immigration. In the 1800s early immigrants were drawn by economic opportunity and made substantial contributions to pivotal economic and historic developments in Canada and the United States, such as mining gold and building the transcontinental railroads. Eventually the Chinese established communities in many principal North American cities. From the mid-1800s until the early part of the century periods of isolation or peaceful coexistence, punctuated by outbreaks of intolerance and “scapegoating,” characterized the relationship of the dominant culture to Chinese settlers, especially in the west (3). It is safe to say that in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the unique medical and diverse cultural traditions of this ethnic minority were not valued. Hostility toward the Chinese culminated in legislation in California officially denigrating the Chinese race and specifically excluding Asians from immigration quotas in 1880 (3, 4). In the United States, Asian healing systems such as acupuncture were not of much interest to the dominant culture until the 1970s following the renewal of relations with China (5).

Over the last four decades there have been subsequent waves of Chinese immigration (2, 4). Chinese immigration increased dramatically when in 1965 immigration policies toward Asians were liberalized. Separate immigration quotas were introduced for mainland China and Taiwan enabling a 10-fold increase in specific immigration from each country. During the Southeast Asian wars large numbers of ethnic Chinese fled Southeast Asia as refugees. In the 1990s events such as Tiananmen Square provoked an exodus from mainland China. Finally, in 1997 Hong Kong’s return to China stimulated a unique movement of families from both Hong Kong and Taiwan (6, 7). This increased rate of immigration has resulted in a twenty-first century North American ethnic Chinese population that is heterogeneous and largely foreign-born (1, 2). While the early Chinese arrivals have acculturated to western language and lifestyle, recent arrivals have been identified as an underserved group that require special attention from public health professionals because of low acculturation levels, low English proficiency, and relative cultural isolation in the new and historic “Chinatowns,” of many urban centers (8).

Cervical cancer rates are higher among Chinese women in California and British Columbia than among non-Latina white women because of poor compliance with cervical cancer screening guidelines. According to Los Angeles data, the rates of invasive cervical cancer among Chinese and non-Latina white women are 12.3 and 7.2 per 100,000, respectively (9). Similarly, Chinese in British Columbia have twice the invasive cervical cancer risk of whites (10). Moreover, data from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program show that Asian-born Chinese women have higher cervical cancer incidence rates than do Asian women born in North America (13.3 versus 9.8 per 100,000 women) (Personal communication, Stephen Schwartz, FHCRC). Few reports have addressed Papanicolaou (Pap) testing levels among women of Chinese origin. However, nearly one half (45%) of Chinese women who participated in an ethnically focused Behavioral Risk Factor Survey conducted in Oakland during 1989–90 had never been screened for cervical cancer, and only 37% of respondents to a 1994 San Francisco survey were routinely obtaining Pap smears (11, 12). Additionally, Archibald et al. showed that Chinese residents of British Columbia are about 25% less likely to complete routine Pap testing than the Province’s general population (10).

To be effective, cancer control interventions targeting less acculturated immigrant groups should be based on a thorough understanding of culturally based knowledge, beliefs, and practices (13, 14). To address lack of familiarity with minority health concepts and practices, health educators are increasingly integrating qualitative approaches into the development of diverse types of intervention programs (e.g., AIDS and smoking prevention interventions) as well as screening programs targeting immigrant groups (e.g., Latina women) (13, 15). The qualitative paradigm applies anthropologic research methods to elicit the “insider’s” point of view, and provides a contextual understanding of cultural values and their relationships (15–17). Because qualitative data collection methods allow participants to discuss a wide range of topics, unencumbered by a rigid format, they facilitate the identification of new and unanticipated information (16, 17).

Our project, Cervical Cancer Control in North American Chinese Women, had three primary objectives: 1) obtain information about reproductive health beliefs and practices relevant to cervical cancer screening among ethnic Chinese women, 2) design culturally and linguistically appropriate interventions to increase Pap testing completion rates among less acculturated women, and 3) conduct a randomized trial to evaluate the effectiveness of intervention approaches. As part of this effort, we completed a qualitative study focusing on concepts and practices that define reproductive health and illness, and cervical cancer screening in particular among Chinese Americans and Canadians. This paper summarizes how we obtained cultural information and developed educational materials and interventions informed by these findings.

BACKGROUND

Study Setting

Our study sites are two west coast cities: Seattle, Washington, and Vancouver, British Columbia. While these metropolitan areas are only 150 miles apart, they vary with respect to their Chinese populations. First, the two cities differ in regard to countries of origin. Both have ethnic Chinese populations from mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia. However, most Seattle migrants are from mainland China, while the majority of Vancouver migrants are from Hong Kong (18, 19). Second, the size and density of the Chinese communities are quite different. While Seattle has individual census tracts with a relatively high proportion of Chinese, they comprise only a small percentage of the total population (18). In contrast, 1991 Canadian Census data show that one in four Vancouver residents are of Chinese descent (20). Additionally, Canada and the United States have different systems for the provision of medical care and preventive services such as Pap smears (21).

Community Involvement

Active community involvement and reciprocal participation are crucial components of successful programs targeting minority populations (22, 23). This project formed a coalition of Chinese women in each study city to help develop educational materials and implement project activities. Coalition members include representatives from Asian service organizations as well as Chinese health care providers. Community advisors who live in the project’s target neighborhoods were also recruited with the assistance of our coalitions. These advisors are less acculturated with respect to Western society and have previous community organization experience at the “grass-roots” level.

QUALITATIVE DATA COLLECTION

Methods

We completed 87 unstructured interviews (43 in Seattle and 44 in Vancouver) with Chinese women. To verify information collected during one-to-one interactions, nine focus groups were conducted (four in Seattle and five in Vancouver), the focus groups comprised 30 women some who had been previously interviewed individually, joined by others who had not. The qualitative data participants were recruited by community advisors, coalition members, and clinic medical interpreters as well as Chinese women’s social networks. Many of the interviewees had received Pap tests. All the interviews and focus group sessions were conducted in a Chinese dialect by bicultural Chinese-American or Chinese-Canadian female interviewers who were fluent in Cantonese and/or Mandarin as well as English. Focus groups were grouped according to language preference. Participants received a small stipend payment as a token of appreciation for their time. The qualitative data were systematically audio-taped, translated, transcribed, edited, and coded by five individuals (four of whom are of Chinese or other Asian descent) for thematic content. Inconsistent coding was reviewed by the team of coders and mutually agreed upon thematic codes were applied.

Anthropologic approaches to data collection follow an iterative process. This means that each interview and focus group introduces new information to be validated and then applied during subsequent data collection. While the parameters of sampling and data retrieval that allow for statistical inference and analysis are not met, this approach allows questions to be reframed as the data are collected, according to the linguistic and cultural framework of the target group (24). By this we mean that subsequent interviews build on information retrieved and validated during previous interviews so each interview increases in specificity and detail. Since cervical cancer is an unfamiliar concept for some Chinese women, our earlier interviews focused on the more familiar aspects of gynecologic health (e.g., knowledge of female anatomy) (7). Women’s health issues of importance to Chinese were identified and each mentioned issue was discussed in terms of causation, prevention, biomedical and traditional treatments, and implications (25, 26). This approach also allowed us to identify relevant words and phrases commonly used by Chinese women (15). The understanding of biomedical and traditional models of gynecologic health was also explored. Later interviews were less exploratory, with an increasing focus on specific issues related to cervical cancer such as knowledge of risk factors, beliefs about Pap testing, and logistic barriers to screening participation.

Results

The average age of the qualitative interview participants was 54 years (range 29–72). Over two thirds (68%) of the women reported their primary language was Cantonese and the remainder were Mandarin speakers. All were Asian born; 34% were from mainland China, 37% from Hong Kong, 17% from Southeast Asia, and 11% from Taiwan. The mean educational level was 11 years (range 0–16) and length of time in North America 11 years (range 1–40). Fifty-seven percent spoke English “poorly” or not at all. The interviews identified many sociocultural factors relevant to Pap testing programs targeting Chinese women. A complete reporting of the qualitative data is in preparation; here we report only those findings pertinent to the video development. These included a traditional orientation to the etiology, prevention, and treatment of gynecologic disease. The central importance of Chinese cosmology in medical theory and its expression in a traditional woman’s daily life is reflected in many small ways. Diet, physical activity, herbal preparations, and attention to the presence of “wind,” “cold,” or “dampness” are references to underlying principles of Chinese medical theory and qi circulation, the balance of yin and yang, and connection between the individual, lifestyle, and environment. The professional terminology and complexities of Chinese medical practice are unknown to most lay women. However, their choice of herbal soups, cautionary tales about risk behaviors, and a preoccupation with balancing forces of yin and yang in nature speak to cultural inclusion of many Chinese medical principles, even as women acculturate to modern life.

For example, many respondents mention that one of the most vulnerable stages of a woman’s life is a period of 1–3 months (depending on region of origin) immediately after childbirth, known as the “sitting month.” During this period of time a woman is depleted of blood and heat through the birth of her baby. She is “blood deficient” and particularly vulnerable to blood loss, as well as invasion by “wind and cold.” Women are therefore advised to avoid taking baths, eating “cold” foods (e.g., acidic fruits), and exposing themselves to “wind.” In addition, women are encouraged to rest, minimize physical activity, and build their blood through diet and herbs known to encourage the circulation of blood and qi (e.g., vinegar–ginger pork soup). If a woman observes these dietary and behavioral recommendations, she protects herself from future problems related to blood deficient, cold states such as headache, arthritis, and many other symptoms. These traditional practices were felt to have more relevance to reproductive health than routine gynecological exams.

The cervix is an anatomic part not often identified in lay Chinese, whereas the uterus as a whole is more commonly discussed. Problems with the uterus are related to the postpartum period if there were specific violations of postpartum practices. Uterine problems may also be related to exposure to “toxins” through poor hygiene, sexual promiscuity, a spouse’s promiscuity, diet, or environmental factors. For example, many participants reported that women are only at risk for cervical cancer if they (or their partners) have had multiple sexual contacts and/or a sexually transmitted disease in the past, are currently sexually active, or are premenopausal. Cancer itself is considered to be a later stage of the blockage of circulating blood and stagnant qi, a process which takes years and which, if unresolved, results in a tumor. Once formed the tumor can progress to cancer.

Treatment was traditionally focused on activities and herbs that would treat exposures to “cold” and “wind,” the symptoms of STDs, or dissolve the tumors through improved blood and qi circulation. As a corollary of this, some women are concerned that cancers are life threatening, and very difficult to treat. Dietary changes are made to treat cancers, and herbal soups are used for treatment. It is understood that the treatment process will be slow and perhaps ineffective since the disease has often progressed for too long. The idea that simple technologies can find cancers early, before they are life threatening is new and unfamiliar, to many less acculturated Chinese women.

Western medicine’s focus on a particular anatomic location fails to recognize an acknowledgment of the traditional Chinese emphasis on balance. From the perspective of less acculturated Chinese women a discussion of cancer is a focus on a problem at a late stage of development, and addresses the dreaded consequences of a process that should have been attended to earlier, rather than focusing on treatable abnormal tissue. The idea of sampling cervical cells by Pap testing and later removing diseased tissue requires an understanding of cellular processes and technology unknown by many less acculturated Chinese women. Consequently, Pap testing, which is widely available, is unknown by some, and considered unnecessary by others who feel the root of the issue is stagnant qi which results in retained blood and cold and wind. These deficiencies and accumulations must be treated or more problems will ensue.

Many participants believed that a person’s health is in constant flux, and so a physician can always find “something that may turn out to be nothing,” and “if you look for trouble, you will find it.” Therefore, Pap testing in the absence of symptoms (e.g., vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, or pelvic pain) takes the unnecessary risk of finding a problem that will self-correct. There is also a deeply embedded cultural predisposition for elegant inaction according to Confucian and Taoist principles. Without being articulated specifically, this approach reflects a general admonition to allow things to be true to their own nature.

The possibility that early detection might result in surgery is a concern for some Chinese women. Experience with surgery in Asia influences women’s view of surgery in North America. Surgery is performed in China infrequently and only for severe problems. Participants reported they perceive the mortality rate from surgery and subsequent infections to be high. Many women do not appreciate that surgical technology and medical care is substantially different in industrialized nations. Surgery is believed to distort the appropriate flow of qi and blood through the body. A fear of surgery and its avoidance at all costs persists. Screening activities that may reveal a need for surgery is yet another example of “looking for trouble” unnecessarily. In addition, Chinese culture values fertility highly, and a woman who has had a hysterectomy before having a child may feel that she is a disappointment to her in-laws and her own family.

In addition to cultural models of illness, logistic issues also were mentioned by interviewees. During our interviews women consistently cited the following logistic issues as barriers to preventive care: problems with appointment scheduling (because of language issues), difficulties finding transportation to health care facilities and childcare during clinic visits, a lack of female providers and medical interpreters, and a paucity of health education materials that are culturally and linguistically appropriate for Chinese women. Another barrier is the lack of access to providers that many women perceive as the only appropriate person to do the test. In countries such as mainland China and Hong Kong, gynecologists routinely provide all women’s health care including Pap tests. Older physicians trained in Asia often continue to encourage referral to gynecologists. Therefore, some of the Vancouver participants were not comfortable seeing a general or family practitioner for cervical cancer screening (a primary care provider referral is necessary for specialist care in British Columbia). In Seattle, lack of health insurance and concerns about cost deterred women from completing cancer screening tests (Canada has a universal access health care system and Pap testing is free). Pap testing facilitators included previous family planning and obstetric services in North America as well as physician recommendations.

INTERVENTION DEVELOPMENT

Video

Video is increasingly being used as a medium for health promotion, and is particularly useful for cancer education in immigrant communities because of low literacy levels and high rates of VCR ownership (27, 28). Additionally, culturally sensitive audiovisual presentations allow recommended behaviors to be modeled in appropriate and supportive contexts, incorporating both cognitive and affective influences (28, 29). They also allow for cultural context to be displayed in a manner that assumes those sending the message understand the daily lives of the target audience; cultural barriers can be acknowledged and addressed quickly. Four versions of the video were produced. A Cantonese version and a Mandarin version, as well as both versions with English subtitles. An increasing body of information supports an entertainment context for the delivery of health education messages (27, 30). Therefore, the video is in an education–entertainment (“soap opera”) format which has been successfully used in health promotion efforts targeting ethnic minority groups in North America as well as audiences in developing countries (30, 31).

The video script was developed with two working groups to review content, the community coalition described earlier, and Fairchild Television. These were not the same people that were interviewed, but a separate group of 28 Mandarin and Cantonese speaking Chinese individuals. Fairchild Television is a corporation operating the only two trans-Canadian all Mandarin and all Cantonese television and radio stations. Their expertise in developing materials for the North American Chinese-speaking market is considerable. Once the general ideas were approved by a focus group, these two groups worked interactively until a final script and eventually a final product was produced that was acceptable to lay, professional, and media sectors of the community.

The video story line focuses on an older, less acculturated Chinese woman’s discomfort and anxieties about persistent pelvic symptoms, and how she was encouraged to get gynecologic care by family and friends. Cultural attitudes, approaches, and barriers to timely care are identified and addressed through interactions with her daughter, friends, a Chinese herbalist, and health care providers at a Western clinic. The video provides cultural context so the audience knows that their traditional values are accepted and understood. For example, references are made to “the sitting month” and the process of replenishing qi and blood using herbal soups common to Chinese medical therapeutics. The significance of milestone birthdays, references to modesty, and the tension between generations over traditional practices are incorporated into the story. In this way the fabric of every day life for Chinese women is recognized. In turn, this is intended to send the message to our target audience that the video producers and outreach workers understand the routine issues of their lives and feel that Pap testing is relevant. The qualitative work identified the central themes to be included. More examples of how we used the qualitative data to develop the video are given in Table I.

Table I.

Use of Qualitative Data to Develop Video Content

| Qualitative finding | Video content |

|---|---|

| Many Chinese immigrants believe traditional remedies should be used to prevent and treat gynecologic disease | Traditional practices such as avoiding hair washing and eating certain soups in the early postpartum period are recognized in multiple scenes

A young, bicultural Chinese woman urges her less acculturated mother to see a Western doctor as well as a Chinese herbalist for her gynecologic symptoms A Chinese herbalist asks the Chinese mother to see a Western doctor when traditional remedies fail to cure her gynecologic symptoms |

| Chinese women often think that Pap testing is only necessary for women who are symptomatic, sexually active, have multiple partners, or are premenopausal | Two women watch a Chinese language news segment on the television; the presenter discusses high rates of cervical cancer among Chinese women, the importance of detecting asymptomatic disease, and the necessity of Pap testing for all women |

| Women are frequently unfamiliar with early detection concepts and Pap testing | The Chinese news presenter discusses early detection and provides a simple description of the Pap smear procedure

A Chinese woman tells a friend that her sister died of cervical cancer, and discusses how her death could have been avoided by early detection |

| Pap tests are perceived as painful and uncomfortable | A clinic nurse reassures a Chinese woman that Pap testing is not painful |

| Women are embarrassed by pelvic exams, especially if they have to see male providers | A Chinese woman tells a friend that although she found her first pelvic exam embarrassing, she got used to the procedure very quickly

The Chinese herbalist provides the Chinese mother with information about a clinic that has female Chinese doctors and nurses The clinic nurse offers a Chinese woman an appointment with a female provider for her gynecologic checkup |

Written Materials

Culturally and linguistically appropriate print materials have been successfully used in disease prevention programs targeting minority groups, and can enhance Pap testing and smoking cessation (32, 33). A motivational pamphlet, featuring drawings of women by a Chinese artist as well as Chinese and English text, was developed for this project. Multiple barriers to screening are addressed through testimonials from Chinese women together with relevant facts (Table II). In addition, a question and answer section is used to address other barriers including lack of physician recommendation, perceptions that Pap testing should be done only by gynecologists, and concerns about embarrassment as well as pain and discomfort. We also used a simple, factual pamphlet about cervical cancer and Pap testing that was recently developed by the Federation of Chinese-American and Chinese-Canadian Medical Societies. Finally, the project developed fact sheets for use in each of the study cities. The Seattle fact sheet provides information about clinics that offer Chinese dialect interpreter services and health insurance coverage for Pap testing. Similarly, the Vancouver fact sheet provides information about Chinese-Canadian physicians as well as a local Pap testing clinic specifically for Asian women, and a statement indicating the medical services plan of British Columbia pays for cervical cancer screening.

Table II.

Examples of Pamphlet Content

| Testimonials | Facts |

|---|---|

| I am 56 years old and spend most of my time doing housework and taking care of children. I have been blessed with good health all my life. My husband, my children, and grandchildren are all healthy. I cook “bou” (replenishing) soups, take anticancer herbs, and do light exercise whenever possible. I observed the sitting month rituals and practice women’s health hygiene. I heard my friends and daughters talk about Pap testing but I don’t think women like me need one. | Women can develop cervical cancer at any age. All women, healthy or not, rich or poor are at risk of developing cervical cancer. Getting a Pap test is a smart thing you can do to take care of your health. The test is like a pair of eyes that can see things your own eyes cannot see. It can tell you whether you have a cervical problem or not. The Pap test gives you a jump-start on taking care of yourself before any problem becomes too big.

Cervical cancer is a preventable disease. Getting a Pap test regularly can detect cancer early and prevent cancer from becoming worse. A Pap test can help you stay healthy. |

| My mom never gets a Pap test. She keeps saying that she does not need one because she is old, no longer has periods, and has stopped having a sex life since her husband died. She feels too embarrassed to let a doctor examine her “down there.” Also, she is scared of hearing bad news about the Pap test result. I believe my mom should have a Pap test. In fact, I will go so she can go with me. | Many cervical cancers occur in women who are postmenopausal and who are no longer sexually active.

Herbal medicine and traditional health promotion practices go hand in hand with Pap testing. One does not keep you from using the other. |

Barrier-Specific Counseling

Cultural attitudes to problem solving, family life, female fertility, and concepts of health and illness are in themselves the fabric of a Chinese woman’s life; to call them “barriers” reduces them to a single dimension, specifically the view of the health care system. Yet, it is true that complexity of life can make Pap testing tangential to more pressing domestic issues. Outreach workers were middle-aged women who have been married, some have children of their own. They were selected after a careful interview process involving project staff and members of the Chinese community. They were ethnic Chinese women for whom English is a second language. They had either high school or college education. They grew to adulthood in Hong Kong, Taiwan, or China, before immigrating to the United States. They were trained by project staff for 3 days about the specifics of cervical cancer, Pap tests, common objections to having examinations and how to address them, and community resources needed by low-income women. By virtue of age, motherhood, cultural knowledge, and training, the project staff felt they had credibility with less acculturated Chinese women. Through training and review of the qualitative material they have been familiarized with details of Chinese culture they may not have known first hand. They have also been encouraged not to discount traditional practices of Chinese women, but to work with women to explain the relevance of Pap testing as a simple technology that can complement traditional approaches to health promotion.

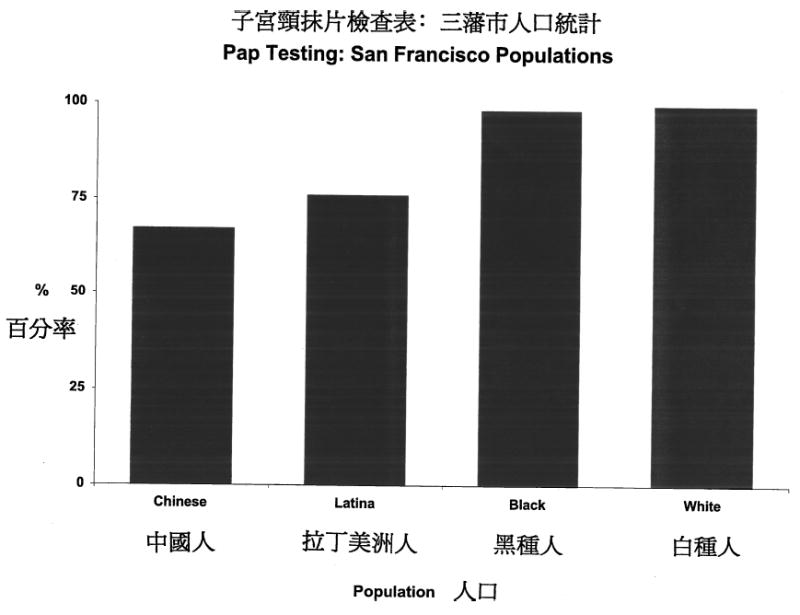

The qualitative data findings were the basis of barrier-specific counseling information for the outreach workers (34). In practice the scripts are modified by the outreach worker to be appropriate for the age, educational level, and concerns of the individual. However, the script can be relied upon as a backup measure in the event that an outreach worker is at a loss for what to say. The information summarizes the barriers to Pap testing that may be raised by Chinese women, and provides scripted responses. Specifically, 12 potential barriers are addressed: Table III summarizes the barriers that were mentioned in our interviews and the frequency with they arose. It is important to remember that the interviews were not structured so that topics emerging in one interview may not have emerged in others. Nevertheless, the table summarizes the number of interviews in which the topic was discussed. Table IV provides an example of the barrier-specific counseling summary for transportation problems. During Pap testing discussions, the outreach workers show diagrams of female anatomy, specula and Pap testing kits, black and white photographs of a Chinese woman physician taking a Pap smear from an Asian patient, and graphs demonstrating high cervical cancer rates as well as low Pap testing levels among Chinese women (Fig. 1).

Table III.

Principle Barriers

| Barrier | % of interviews |

|---|---|

| Embarrassment | 36.6 |

| Lack of knowledge | 25.9 |

| Not necessary | 25.1 |

| Costly | 20.9 |

| Can’t communicate/need interpreter | 15.9 |

| Fear of pain | 15.6 |

| Fear of finding bad news | 11.8 |

| Transportation | 8.2 |

| Inconvenient | 2.4 |

| Need childcare | 2.4 |

| Waste of government resources | 2.4 |

| No good physicians available | 2.4 |

Note. N = 87. These are the most commonly discussed barriers, but not all barriers were given an equal opportunity to be discussed. Not every interview attempted to touch on these subjects. Some interviews may have spent the entire hour and a half discussing nonbarrier-related topics at length.

Table IV.

Barrier-Specific Counseling Example: Transportation Barriers

| Counseling guidelines | Suggested responses |

|---|---|

| Find out what transportation problems the woman has | Do you have a way of getting to the clinic?

How do you usually get to shops and other places? Do you have any relatives that could drive you to the clinic? |

| If she has no relatives that can help, suggest asking a friend or neighbor to drive her? | Our community has a long tradition of helping one another

Do you have any friends or neighbors that could drive you to the clinic? Maybe you could help with childcare sometime in return? |

| If she is used to taking the bus, provide bus route information. Offer two bus passes | There is a good bus service to your clinic. I can tell you which bus to take

I could give you a couple of bus passes if that would help |

| If there is no support available and she is not comfortable taking the bus, offer to arrange taxicab transportation | We could arrange for a taxi to take you to the clinic and bring you home again if that would help |

Fig. 1.

Example of visual aid.

Intervention Efficacy

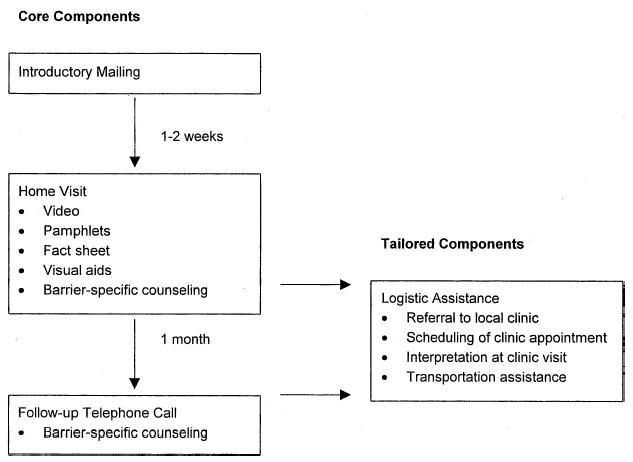

The intervention materials have been evaluated in a randomized controlled trial. Two cervical cancer control intervention approaches for women who do not utilize Pap testing were implemented. Women randomized to the “high intensity” intervention were visited by a female Chinese outreach worker and received a subsequent follow-up telephone call (Fig. 2). During home visits, women were given a video as well as written educational materials. In addition, outreach workers provide barrier-specific counseling, using various visual aids to reinforce educational messages, and offering tailored logistic assistance (e.g., medical interpretation during a clinic visit). The “low intensity” intervention was a direct mailing of the video and written materials. Women in the control arm of the evaluation received the services that are currently available to the community (35).

Fig. 2.

Summary of outreach worker intervention.

Using self-reported Pap testing in the past 2 years as the outcome of interest, 61% of women randomized to the “high intensity” outreach worker arm received Pap testing. Forty-seven percent of the women randomized to the mail only, “low intensity” arm reported having received a Pap test, while 34% of the controls reported having been screened within the preceding 24 months. All three of the possible pairwise comparisons were significant (p < 0.05). Thus, the intervention materials were most effective when explained by a bilingual–bicultural outreach worker who assisted with logistical barriers, but the pamphlet and video alone were successful and influential when mailed to women when compared to a control group of Chinese women (35).

DISCUSSION

Hubbell et al. have previously described their anthropologic approach to developing a breast cancer control program for Latina women in California (13). They found that many Latinas did not embrace medically accepted risk factors (e.g., a family history of breast cancer), but did believe that other factors (e.g., breast trauma) increase the risk of contracting breast cancer. Additionally, this group reported that fatalistic attitudes (e.g., believing breast cancer is a “punishment from God”) were a barrier to the use of screening procedures among Latina women. Similarly, we have previously found that Cambodian refugees believe that traditional practices help to protect women from uterine disease, and perceive that karma plays a substantial role in determining the course of one’s life, including their health (27). These are examples of unique culture-specific barriers to care.

To overcome the objections of Chinese women to obtaining Pap testing requires that the health educator understand the nature of the objection within the community and cultural context. Only then can plausible problem solving be explored with women by educators. By interviewing community women and incorporating their practices and common concerns and beliefs into our materials, the project staff began the conversation with women about Pap testing in a knowledgeable, empathetic, and meaningful way. By encouraging the outreach workers to respectfully raise these issues and address them together with women, outreach workers validated Chinese culture and practices and negotiated Pap testing in that context.

Coyne and colleagues conducted a literature review of factors associated with cervical cancer screening (36). This review found that individual barriers to screening as well as their relative importance differ markedly between population subgroups. For example, Spanish-speaking Latinas are more likely to report that they find Pap smears embarrassing and frightening than do English-speaking Latina women. As might be expected logistic issues such as transportation, childcare, and concern about using scarce resources for unnecessary tests are more important among socially disadvantaged and minority women, than among middle class white women. Such barriers are shared by low income women of diverse ethnic backgrounds. For the female population as a whole, these authors concluded that the most important barriers to Pap testing are perceptions that it is unnecessary, fear of embarrassment, and lack of physician recommendation.

The most cost-effective approach to health promotion may involve tailoring interventions by culture as necessary, and reaching across cultures when possible (31, 37). The effectiveness of this intervention among Chinese women provides an example of how a programmatic approach might be implemented among several immigrant populations (35, 38). Specifically, the use of bicultural outreach workers for program delivery, the provision of logistic assistance accessing health care, and the use of linguistically appropriate materials would be relevant to multiple immigrant groups. However, the specific content of educational messages would need to be tailored to each community. In addition, the impact of the materials alone, without logistical assistance, among the mail only arm suggests that culturally relevant materials alone can motivate women to get Pap testing. Logistic assistance has an additive effect, and improves self-reported Pap testing rates even more.

Our work to tailor materials for Chinese women provides an example of the unpredictable beliefs and practices that can be revealed by using qualitative methods during the design of health education programs targeting immigrant communities. Many educational programs for minority groups may have been ineffective because a health problem was not addressed within the context of their ethnic history, cultural values, community politics, and contemporary lives (39). Redress of historical inequities and exclusionary legislation directed against the Chinese immigrant community may never be adequate. In our opinion ignoring the significance of this history for this community is unconscionable. The National Institutes of Health have lately prioritized funding to include minority cultural perspectives in scientific initiatives (40, 41). Prioritization of minority health research may reflect a tacit recognition of current and past inequities. Our intervention program is an effort to respond to these priorities and contextualize available medical technology for one of the many minority communities that have contributed to North American society for over a century.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant Nos. CA74326 and U01 CA86322 from the National Cancer Institute. Our project works closely with coalition members from Seattle, Washington, and Vancouver, British Columbia’s Chinese community. We acknowledge the coalitions, community advisors, and project staff for their support and dedication. Furthermore, we thank the Chinese interviewers for their outstanding work and the Chinese women for sharing their stories with us.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau: Census 2000 Profile

- 2.Costa R, Renaud V. The Chinese in Canada. Can Soc Trends. Winter 1995;39:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hull El. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 1985. Without Justice for All. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waddell B. United States immigration: A historical perspective. In: Loue S, editor. Handbook of Immigrant Health. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leslie C, Young A. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1992. Introduction: In Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasky EM, Martz CH. The Asian/Pacific Islander population in the Unites States: Cultural perspectives and their relationship to cancer prevention and early detection. In: Frank-Stromberg M, Olsen SJ, editors. Cancer Prevention in Minority Populations—Cultural Perspectives for Health Care Professionals. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mo B. Modesty, sexuality, and breast health in Chinese women. West J Med. 1992;157:260–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gould-Martin K, Ngin C. Chinese Americans. In: Harwood A, editor. Ethnicity and Medical Care. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkin DM, Muir CS, Whelan SL, Gao YT, Ferlay J, Powell J. Vol. 6. Lyon, France: International Agency Cancer Research; 1993. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archibald CP, Coldman AJ, Wong FL, Band PR, Gallagher RP. The incidence of cervical cancer among Chinese and Caucasians in British Columbia. Can J Public Health. 1993;84:283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control. Behavioral risk factor survey of Chinese—California, 1989. MMWR. 1992;41:266–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M, Lee F, Stewart S. Pathways to early beast and cervical cancer detection for Chinese American women. Health Educ Q. 1996;23(Suppl):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubbell FA, Chavez LR, Mishra SI, Magana JR, Valdez RB. From ethnography to intervention: Developing a breast cancer control program for Latinas. Monogr Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;18:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen SJ, Frank-Stromberg M. Cancer prevention and early detection in ethnically diverse populations. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1993;9:198–209. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(05)80036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steckler A, McLeroy KR, Goodman RM, Bird TL, McCormick L. Toward integrating qualitative and quantitative data for health education planning, implementation, and evaluation. Health Educ Q. 1992;19:101–115. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gittelsohn J, Pelto PJ, Bentley ME, Pertti J, Pelto J, Nag M, Ooman N. Qualitative methodological approaches for investigating women’s health in India. In: Gittelsohn J, Pelto PJ, Bentley ME, Nag M, Ooman N, editors. Listening to Women Talk About Their Health—Issues and Evidence from India. New Delhi, India: Har-Arand Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sensky T. Eliciting lay beliefs across cultures: Principles and methodology. Br J Cancer. 1996;74(Suppl):63–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Commerce. Washington, DC: Department of Commerce; 1993. 1990 Census of Population and Housing: Population and Housing Characteristics for Census Tracts and Block Numbering Areas—Seattle, WA PMSA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Con H, Con RJ, Johnson G, Wickberg E, Wilmott WE. Toronto, Canada: McLelland and Stewart; 1992. From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chard J. Vancouver’s diverse and growing population. Can Soc Trends. 1995 Autumn;:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson GH, Boyes DA, Benedet JL. Organization and results of the cervical cytology screening program in British Columbia, 1955–1985. BMJ. 1988;296:975–978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6627.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montes JH, Eng E, Braithwaite RL. A commentary on minority health as a paradigm shift in the United States. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9:247–250. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1992. Health Behavior Research in Minority Populations: Access, Design, and Implementation. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spradley JP. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1979. The Ethnographic Interview. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanani S, Latha K, Shah M. Applications of qualitative methodologies to investigate perceptions of women and health practitioners regarding health disorders in Baroda slums. In: Gittelsohn J, Bentley ME, Pelto PJ, Nag M, Ooman N, editors. Listening to Women Talk About Their Health—Issues and Evidence From India. New Delhi, India: Har-Arand Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chavez LR, Hubbell FA, McMullen JM, Martinez RG, Misha SI. Structure and meaning in models of breast and cervical cancer risk: A comparison of perceptions among Latinas, Anglo women, and physicians. Med Anthropol Q. 1995;9:40–76. doi: 10.1525/maq.1995.9.1.02a00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahloch J, Jackson JC, Chitnarong K, Sam R, Ngo LS, Taylor VM. Bridging cultures through the development of a Cambodian cervical cancer screening video. J Cancer Educ. 1999;14:109–114. doi: 10.1080/08858199909528591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gagliano ME. A literature review of the efficacy of video in patient education. J Med Educ. 1988;63:785–793. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yancey AK, Walden L. Stimulating cancer screening among Latinas and African American women: A community case study. J Cancer Educ. 1994;9:46–52. doi: 10.1080/08858199409528265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogers EM. The field of health communication today: An up-to-date report. J Health Commun. 1996;1:15–23. doi: 10.1080/108107396128202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane SD. Television and mini-dramas: Social marketing and evaluation in Egypt. Med Anthropol Q. 1997;11:164–182. doi: 10.1525/maq.1997.11.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen MS, Zaharlick A, Kuun P, Li WL, Guthrie R. Implemention of the indigenous model for health education programming among Asian minorities: Beyond theory and into practice. J Health Educ. 1992;23:400–403. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor V, Hislop G, Jackson JC, Tu SP, Yasui Y, Schwartz S, Teh C, Kuniyuki A, Acorda E, Marchand A. An evaluation of two cervical cancer screening interventions for Chinese women in North America. In APHA 2001 Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcus AC, Crane LA, Kaplan CP, et al. Improving adherence to screening followup among women with abnormal Pap smears. Med Care. 1992;30:216–230. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King ES, Rimer BK, Seay J, Balshem A, Engstrom PF. Promoting mammography use through progressive interventions: Is it effective? Am J Public Health. 1994;84:104–106. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coyne CA, Hohman K, Levinson A. Reaching special populations with breast and cervical cancer public education. J Cancer Educ. 1992;7:293–303. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasick RJ, D’Onofrio CN, Otero-Sabogal R. Similarities and differences across cultures: Questions to inform a third generation for health promotion research. Health Educ Q. 1996;23(Suppl):142–161. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson JC, Taylor VM, Chitnarong K, Mahloch J, Fischer M, Sam R, Seng P. Development of a cervical cancer control intervention program targeting Cambodian American women. J Commun Health. 2000;25:359–377. doi: 10.1023/a:1005123700284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michielutte R, Sharp PC, Dignan MB, Blinson K. Cultural issues in the development of cancer control programs for American Indian populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1994;5:280–296. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu E, Liu WT. US national health data on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders: A research agenda for the 1990s. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1645–1652. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.12.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The National Human Genome Research Institute. Research supplements for underrepresented minorities. [Retrieved Feb 9, 1996];25(3) http://www.nhgri.nih.gov/Grantinfo/Funding.