In the United Kingdom over 22% of the adult population is now obese, with multiple health problems related to a body mass index—weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in metres) squared—of 30 or higher. In England the national service frameworks for diabetes and coronary heart disease highlight the importance of helping patients who are obese. People continue to gain weight until their 50s and 60s, so 30-40% of older people will be obese, with chronic disease, mobility problems, and depression aggravated by obesity.

Figure 1.

Obesity needs to be managed like any other chronic disease—with empathy and a non-judgmental professional attitude. Helping people to manage their weight is difficult and can be discouraging and time consuming for health professionals.

Table 1.

Resources for health professionals

| • www.nationalobesityforum.org.uk (National Obesity Forum) |

| • www.domuk.org (Dietitians in Obesity Management UK) |

| • www.aso.org.uk (Association for the Study of Obesity) |

| • www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=296567 (draft guidance from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) (accessed 1 Aug 2006) |

High relapse rates, apparent lack of effectiveness, and lack of training and resources are major obstacles. However, an increasing evidence base exists for the effective management of obesity. And resources for health professionals are also now available.

Table 2.

Achievable weight change (95% confidence intervals) from meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials in adults

|

Weight change (kg) at 1-3 years |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trials | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|

Lifestyle interventions v control |

|||

| Deficit of 600 kcal/day,* or low fat diet |

−5.3 (−5.9 to −4.8) |

−2.4 (−3.6 to −1.2) |

−3.6 (−4.5 to −2.6) |

| Diet and exercise |

−4.8 (−5.4 to −4.2) |

−2.7 (−3.6 to −1.8) |

Not studied |

| Diet and behaviour therapy |

−7.2 (−8.7 to −5.8) |

−1.8 (−4.8 to 1.2) |

Not studied |

| Diet, exercise, and behaviour therapy |

−4.0 (−4.5 to −3.5) |

−3.0 (−3.6 to −2.4) |

−2.0 (−2.7 to −1.3) |

|

Effect of adding exercise |

|||

| Adding exercise to diet |

−2.0 (−3.2 to −0.7) |

Not studied |

−8.2 (−15.3 to −1.2) |

| Adding exercise to diet, plus behaviour therapy |

−3.0 (−4.9 to −1.1) |

−2.2 (−4.2 to −0.1) |

Not studied |

|

Effect of adding behaviour therapy |

|||

| Adding behaviour therapy to diet | −7.7 (−12.0 to −3.4) | Not studied | −2.9 (−8.6 to 2.8) |

Data from Avenell et al (see Further Reading box).

1 kcal = 4.18 kJ.

For people who are obese, long term low fat diets—together with increased physical activity and strategies to help modify their lifestyle—may prevent type 2 diabetes in those with impaired glucose tolerance and improve the control of hypertension and type 2 diabetes. These health benefits are seen with surprisingly small weight losses—5-10% sustained over a year or more, well within achievable goals for weight loss and despite some weight regain over subsequent years.

Table 3.

Important factors to evaluate in patient's history

| • Is the weight problem recent or longstanding (for example, since childhood)? |

| • Consider the patient's successful and unsuccessful attempts at losing weight and establish what he or she thinks about them |

| • What is the patient's attitude to smoking? For example, he or she may not be interested in stopping smoking because they may feel they will gain weight |

| • How does the patient feel about illness and medication? For example, he or she may relate weight gain to inadequate thyroxine replacement, that weight gain is associated with depression |

| • Is there a family history of weight problems? Does the patient's partner have weight problems? |

| • Does the patient believe that their medical, social, or psychological problems are related to their obesity? |

| • What is the patient's motivation for weight loss or stability? |

General strategies for helping a patient with a weight problem include agreeing an individual, realistic, weight loss goal, such as 5-10% over three to six months. Achieving this goal can help motivate success. Aim for weight loss initially, followed by a distinct strategy for weight maintenance. Provide ongoing support and positive feedback; this can be provided in a group setting.

A careful history can provide useful information for weight management. Weight, height, body mass index, and waist circumference (plus cardiovascular risk factors if indicated) should be documented regularly—changes in strategy can be used to help to motivate the patient.

This is the third article in the series

Aims and success criteria

The emphasis for “obesity treatment” used to be on weight loss. But, as identified in the 1996 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network guideline, weight loss is only one element in weight management. Management encompasses:

Weight loss (short term, three to six months)

Weight maintenance (long term, more than six months)

Priority reduction of risk factors.

Successful weight management does not necessarily have to mean weight loss. It can also reflect weight maintenance in somebody who in the past has gained weight.

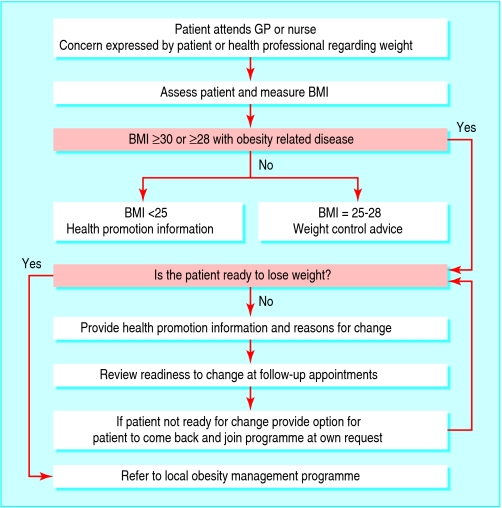

Figure 2.

A possible pathway for starting weight management to provide support appropriate to the stage. Adapted from Counterweight programme (see Further Reading box)

In general, the diet and lifestyle strategies to achieve weight loss, weight maintenance, and improved risk factors are the same. There may be individual variations in responses to individual components—for example, lower fat or lower carbohydrate diets, or for physical activity.

Table 4.

Web based resources for patients to help with weight control

| • www.realslimmers.com (online food retailer and diet club) |

| • www.eating4health.co.uk (organisation of state registered dietitians offering dietary advice and programmes) |

| • www.fatmanslim.com |

| • www.whi.org.uk (Walking the Way to Health Initiative—aims to get more people walking in their own communities) |

| • www.weightlossresources.co.uk (gives tips and programmes for losing weight) |

| • www.toast-uk.org (The Obesity Awareness and Solutions Trust—campaigning charity offering a help and information line via phone or email; online chat rooms and forum facilities) |

Behavioural change

The key elements to successful behavioural change are frequent contact and support. Group counselling does not seem less effective than individual counselling for long term weight change. Weight loss clubs may be helpful, but evidence is limited. For some people, however, initial individual counselling may be needed, and groups may not be beneficial—for example, for men needing support but whose local group comprises mainly women. If possible, immediate family or key friends should be involved. Beneficial behavioural changes may have knock-on effects for other members of the family.

Table 5.

Examples of commonly used behaviour modification techniques

| Behavioural approach | Techniques |

|---|---|

| Self monitoring |

Daily diary (time of eating, type and amount of food, thoughts and feelings, physical activity); personalised 5-10% weight loss targets; weight monitoring charts |

| Stimulus control |

Patient to identify and record external and internal triggers for eating; negotiate goals (for example, if eats when worried or stressed, to make list of alternative, relaxing activities) |

| Eating behaviour |

Negotiate goals (such as avoid watching television or reading while eating) |

| Cognitive restructuring |

Realistic weight loss expectations of 5-10% discussed at first appointment; achievable dietary and activity goals set in collaboration with patient; patient encouraged to challenge self defeating thoughts with positive thoughts; patient discouraged from using words such as “always” and “never” |

| Nutrition education |

Patient learns how to read food labels; patient learns about dietary goals |

| Relapse management | Patient encouraged to plan in advance how to prevent lapses; management of cravings discussed; patient encouraged to generate list of coping strategies for high risk situations |

Weight loss plans move through various stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and often relapse. Patients need help to make plans with achievable goals—unrealistically high goals for weight loss lead to disappointment. The goals can be reviewed over time, with a graded approach to changing habits.

Commonly used techniques, such as self monitoring, identifying internal triggers for eating, and creation of coping strategies, can help with behaviour change. There is evidence that these techniques aid weight loss and maintenance. They have been incorporated into a successful model for weight management in primary care in the UK—the Counterweight programme. This programme achieved weight loss results similar to those achieved by the Diabetes Prevention Program Group (see Further Reading box) for those who completed the programme.

Prompts or reminders can be used to help to build better habits. A lapse presents an important opportunity to plan how to deal with the experience next time. Rewards should be planned, and evidence of benefit—in terms of reduction in cardiovascular risk factors or in changes in clothing size—can be helpful. It is important to help to build self esteem and avoid criticism. A diary of food intake and physical activity can prompt discussion about situations that led to a particular behaviour, so that strategies can be planned.

Web based resources are available for patients, and a Haynes manual (Banks I. HGV man manual. Yeovil: Haynes, 2005) has been produced specifically to help men to lose weight.

For effective weight loss, energy intake must be reduced and physical activity increased

For weight maintenance, physical activity is possibly the most important element, but evidence from, for example, the national weight control register, shows that the best results come from continued, cognitive, restriction of energy (especially fat) together with increased physical activity

Diets

Dietitians with skills in weight management can give advice and support to general practices, including information for patients. Diets partly work by imposing a regular regimen. Regular meal times, and the need for breakfast, are important. People who skip meals early in the day often more than make up for this later in the day. Shift workers have particular problems, so it is important to help the patient make his or her own plan.

Figure 3.

Some patients may find that alcohol accounts for a much larger energy intake than they expected. Alcohol can also encourage some people to eat more

Snacking or grazing is best discouraged, but low energy snacks must be available when snacking is unavoidable. Reducing portion sizes, using portion controlled foods (including meal replacements) and limiting the size of plates used may all be helpful. Patients should be advised to avoid having tempting, high energy foods at home, to shop when they are not hungry, and to use a shopping list.

Figure 4.

Concerns have been raised that diets focusing long term on eating mostly protein with small amounts of carbohydrate may increase the risk of osteoporosis and kidney stones (above)

A diary of food intake is a useful starting point for making changes. This may be particularly useful for patients who claim to be unable to lose weight despite eating virtually nothing. A diary may help them to see that they eat more than they thought and is useful for looking at triggers to overeating.

Table 6.

Key principles for a successful diet

| • Include a variety of foods from the main food groups |

| • Limit portion size |

| • Reduce the proportion of fat, particularly saturated fat |

| • Partially replace saturated fat with monounsaturated fat (such as olive oil) or omega 3 polyunsaturated fats |

| • Increase intake of fruit and vegetables to at least five portions a day |

| • Ensure that meals include wholegrain and high fibre foods, and foods with a low glycaemic index |

| • Reduce sugar intake |

| • Limit salt intake |

| • Follow a structured meal plan that starts with breakfast |

New diets appear in the media and on the bookshelves all the time and it can be difficult to counter this barrage. Consistent evidence shows that a long term, low fat diet produces long term weight loss and beneficial changes in lipids, blood glucose, glycaemic control, and blood pressure. Typically, such a diet would have a deficit of 500-600 kcal/day below the current requirement for energy balance, leading to a weight reduction of 0.5 kg a week. A low fat diet can be consistent with providing low glycaemic index foods, as in diets that focus on eating foods with a low glycaemic index. Such a diet provides the best chance for a long term change to healthy eating habits, with protection against chronic diseases such as cancer and heart disease. Low energy meal replacements may be helpful for some patients, but palatability can be a problem.

Very low energy diets may produce better initial weight loss—which might improve motivation—but long term, the weight loss achieved in this way is rarely any greater than the loss achieved with low fat diets. Rapid weight loss may occasionally be required, however (for example, to allow surgery to proceed).

Low carbohydrate, Atkins-type diets (diets that focus on eating mostly protein, with small amounts of carbohydrate) are effective in the short term but less so after a few months. Short term side effects include headache, constipation, halitosis from ketosis, and fatigue. Longer term effects on disease risks have been little studied for these diets. Low carbohydrate diets lead to deterioration of some parts of the lipid profile—for example, low density lipoprotein cholesterol—but improvements in high density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and glycaemic control. Short term use is unlikely to be harmful and can be a starting point for the otherwise poorly motivated patient.

Physical activity

Patients should be encouraged to reduce their inactivity rather than “do more exercise,” which for some people may have negative connotations of team sports and “going to the gym.” Weight loss and long term weight maintenance will be improved if activity levels can be increased. Step counters may be useful to set daily targets, but their value is unclear. As well as its effect on weight loss, increased physical activity has additional benefits for cardiovascular risk factors, insulin resistance, and depression and also limits the loss of lean tissue and contributes to bone health.

Beans on toast, fruit, and porridge are all useful standbys for low energy meal replacements—and they are all easily available and tasty

Keeping physically active helps people to curb excess appetite and avoid situations that prompt eating

Patients who have previously been inactive must decide and plan for themselves how to incorporate more physical activity into their current lifestyle—for example, less sitting and more standing, less television, walking some of the way to work, gardening, and cycling. Walking initiatives in the patient's area may be useful (www.whi.org.uk). Patients may think that they have to go to exercise classes, but this may be unrealistic for their current activity levels and lifestyle. Other people may enjoy attending organised classes and the peer support this provides. Recording physical activity in a diary can be used in much the same way as a diet diary. Patients may find it difficult to attain the levels of moderate activity recommended initially, but this should be the long term goal. Although the Department of Health's recommended goals for physical activity clearly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease for people who are overweight and obese, they are not sufficient to counteract all the ill effects of obesity.

Table 7.

Department of Health recommendations on physical activity for adults*

| • Thirty minutes of at least moderate activity on at least five days a week |

| • For many people, 45-60 minutes of moderate activity a day may be necessary to prevent obesity |

| • People who have been obese and have managed to lose weight may need to do 60-90 minutes of activity daily to maintain weight loss |

| • Recommended levels of activity may be obtained in one session or as bouts of activity of 10 minutes or more |

| • The activity can be “lifestyle” activity (such as walking, cycling, climbing stairs, hoovering, mowing lawn), structured exercise, or sport |

www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/09/88/04080988.pdf (accessed 1 Aug 2006)

Helping someone to change their behaviour to prevent or reduce obesity requires a flexible approach tailored to that individual, with encouragement when, inevitably, setbacks occur.

The ABC of Obesity is edited by Naveed Sattar (nsattar@clinmed.gla.ac.uk), professor of metabolic medicine, and Mike Lean, professor of nutrition, University of Glasgow. The series will be published as a book by Blackwell Publishing in early 2007.

The authors thank Karen Allan for reviewing a previous draft of the article. The cycling photograph is published with permission from Dennis MacDonald/Alamy. The illustration of a drinking party is Heurigen Party, Vienna by Rudolf Klingsbogl, published with permission from Vienna's Musical Sites (1927). The photograph of the kidney stone is published with permission from Stephen J Kraemer/SPL.

Competing interests: In the past five years, Alison Avenell has received one fee for speaking from Roche Products UK, the manufacturer of orlistat. For series editors' competing interests, see the first article in this series.

References

- • Avenell A, Broom J, Brown TJ, Poobalan A, Aucott L, Stearns SC, et al. Systematic review of the long-term effects and economic consequences of treatments for obesity and implications for health improvement. Health Technol Assess 2004;8(21). [DOI] [PubMed]

- • Costain L, Croker H. Helping individuals to help themselves. Proc Nutr Soc 2005;64: 89-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Diabetes Prevention Program Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346: 393-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • National Obesity Forum. Managing obesity in primary care [CD-Rom]. Nottingham: NOF, 2004.

- • Obesity training courses for primary care (from www.domuk.org)

- • Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviours. Am Psychol 1992;47: 1102-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Obesity in Scotland: integrating prevention with weight management. www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign8.pdf (accessed 12 Jul 2006).

- • Counterweight Project Team. A new evidence-based model for weight management in primary care: the Counterweight programme. J Hum Nutr Diet 2004;17: 191-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]