Short abstract

The decision to trust a trainee to manage a critically ill patient is based on much more than tests of competence. How can these judgments be incorporated into assessments?

Competency based postgraduate medical programmes are spreading fairly rapidly in response to the new demands of health care. In the past 10 years, Canada, the United States, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom have introduced competency models and other countries are following.1-5 These frameworks are valuable, as they renew our thinking about the qualities of doctors that really matter.

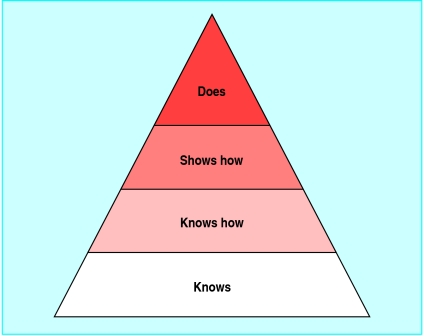

Paramount in these developments is the view that quality of training should be reflected in the quality of the outcome—that is, the performance of its graduates. As postgraduate training almost fully focuses on learning in practice, training and assessment moves around the top two levels of Miller's hierarchical framework for clinical assessment (figure).6 Knowledge and applied knowledge of residents may be interesting, but performance in practice is the real thing. The question is: How can we assess it?

Figure 1.

Miller's pyramid for clinical assessment

Competence does not necessarily predict performance

Competency based training suggests that competence and competencies are what we want trainees to attain. But is this the same as performance? If a doctor is competent, what happens if she does not perform according to her assessed competence? Most authors agree that performance involves more than competence.7 It clearly includes something that cannot easily be caught with traditional assessment methods. One component is willingness to apply your competence.8 But there is more.

Consider two residents, 1 and 2. Resident 1 scored A on the knowledge, applied knowledge, and objective skills examinations whereas resident 2 scored B. Both serve in a night shift in the hospital, and you are on call that week. Each of them faces a critical acute care problem. Resident 1 decides not to call you and manages according to the best of his ability. Resident 2 is hesitant and calls you to discuss the case. Management is then carried out in line with your advice. Which resident, in terms of the “does” level, should receive the highest mark? Who would you trust most to do night shifts? Resident B's behaviour may yield better care than resident A's.

Just as trainees' scores for “knows” and “knows how” do not necessarily predict scores for “shows how,” all these may not predict the “does.” The outcome of care may be more important than the trainee's attributes in terms of knowledge and skill. It is important to grasp this factor, as the movement towards competency based training asks for assessment of outcome at the “does” level.9,10

Different approach to assessment

Specialty associations, universities, and programme directors face the task of devising assessment models related to the new competency frameworks. This is difficult. Let's take the Canadian framework (CanMEDS) as an example. This model states that medical professionals should adequately execute the roles of medical expert, communicator, collaborator, scholar, health advocate, and professional.1 Clearly, these roles are so intertwined that assessing each of them separately would make little sense. Another problem is their broadness. The ability to collaborate in one situation may not predict it for another situation. The same problems hold for other roles and for underlying detailed key competencies formulated within each of these competency frameworks. Attempting to assess them separately may result in a trivialised set of attained abilities.

The sum of what professionals do is far greater than any parts that can be described in competence terms.11 Identifying a lack of competence may be possible, but confirming the attainment of a competency is difficult. To further develop educational technology and sophistication of assessment methods does not seem the right direction.12 This may atomise competencies, increase bureaucracy, and move away from expert opinion and from what really matters in day to day clinical practice. We need another direction.

Maybe we should not focus on competencies but on day to day activities and accomplishments of our trainees and infer the presence of competencies from adequately executed professional activities. These are what expert supervisors can assess. The question is primarily how to optimise expert judgment of clinical performance, given the competency frameworks.

Trust

Here is where trust enters our thinking. We want medical doctors whom we can trust to take care of us, our family and friends, and anyone else. We may distrust incompetent doctors, but we also distrust those who, for whatever reason, do not act according to their ability, those who take too big risks, and those who make mistakes because they work sloppily. If clinical supervisors think of their trainees, they would be able to identify those whom they would entrust with a complex medical task because they will either perform well and seek help if necessary or not accept the task if they don't feel confident. Supervisors often know who to pick, even if they can't tell exactly why.

This gut feeling does not always match with formally assessed knowledge or skill, but it may be more valid for its purpose. No external body or procedure can replace this type of expert judgment. One reason is that trust in the judgment of a supervisor implies a personal involvement in the outcome of the activity of the trainee. If this is your trainee, his or her accomplishments are part of your accomplishments. If it's not done well, you will have a problem.

Entrustable professional activities

Postgraduate training and assessment should not move away from the clinical supervisor in the ward but should instead scaffold the supervisor's role of appraising the execution of activities entrusted to residents. Entrusted, or rather, entrustable activities are not the same as competencies. It is easier to appraise a critical professional activity than a competency, such as health advocate, scholar, or professional. Competencies must be translated to professional activities. As competence is an attribute of a person and activities are part of daily work, they are different dimensions of performance (table). Most activities reflect several competencies and most competencies are applied in several activities.

Table 1.

Relation of professional activities to competencies

|

Competencies*(to be inferred)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entrustable professional activities (to be appraised) | Medical expert | Communicator | Collaborator | Scholar | Health advocate | Manager | Professional |

| Measuring blood pressure | + | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Performing venepuncture | — | + | — | — | — | — | — |

| Performing appendectomy | + | + | — | — | — | — | — |

| Giving morning report after night call | + | + | + | — | — | — | — |

| Designing treatment protocol | + | — | + | + | + | + | — |

| Chairing a multidisciplinary meeting | — | + | + | — | + | — | + |

| Requesting organ donation | — | — | — | + | — | + | + |

From Canadian competencies framework.1

The two questions that now arise are which critical professional activities cover the relevant competencies of the profession and how can supervisors learn when to entrust such activities to a trainee?

The box lists the criteria for entrustable professional activities.13 Identifying these activities for assessment purposes requires analysis of the profession. Procedures developed some decades ago, such as the critical incident technique and job or task analysis, are useful tools.14-16

The recent design of a two year part time postgraduate competency based curriculum for public heath doctors in the Netherlands was based on the analysis of the profession. Fifteen specialists attended two half day meetings and were asked mentally to go through a regular working routine and identify all entrustable professional activitites they could think of. This initially yielded around 40 critical activities, which after discussion were reformulated and led to a list of nine general and 33 specific activities covering the essentials of the specialty.17 The analysis subsequently helped to establish the framework of the curriculum as the activities were all described with matrix links to 28 predetermined competencies and with suggestions on how to observe the trainees' performance in these activities. The idea is that once a trainee has been entrusted to carry out all entrustable professional activities related to a specific competency, this competency is considered to be acquired.

Trust as a tool in assessment

The second question is how we know when we can entrust a critical professional activity to a trainee. In practice, it happens often. The attendant on call is an example. She knows the resident, hears the phrasing of the problem and the tone of a request on the phone, draws a conclusion, and must instantly decide whether to take over or leave the responsibility to the trainee.

Criteria for entrustable professional activities13

Part of essential professional work

Require specific knowledge, skill, and attitude

Generally be acquired through training

Lead to recognised output of professional labour

Usually be confined to qualified staff

Be independently executable within a time frame Be observable and measurable in their process and their outcome

Lead to a conclusion (done well or not well)

Reflect the competencies to be acquired

Summary points

Quality of training should be reflected in performance rather than in competence of graduates

Adequate performance includes the ability and inclination to apply competence in a way that optimises the outcome of professional activities

No external body or procedure can replace expert judgment of accomplishments

Trust by a supervisor reflects competence and reaches further than observed ability

Educators do not fully exploit these gut feelings about trustworthiness for assessment purposes. Yet they may be at variance with marks for a test or even for a clinical evaluation. We need to substantiate the factors that make us decide to trust a trainee to care for critically ill patients. Interestingly, doctors often make decisions in uncertainty. Here, medical decision making parallels educational decision making. Substantial evidence is available on methods that can help medical decision making.18 The same holds for decisions about staff planning, which has everything to do with entrustment of professional work.19 So, why not draw analogies between decision making in education and decision making in health care and human resource management and use similar methods?

Of course, decisions of entrustment have a practical side—if no alternative options are available, over-demanding responsibility is a risk. But probably in most cases, the judgments of supervisors can be justified. The pros and cons are balanced, including giving the trainee a chance to show his ability.

Decisions of entrustment also have a substantial element of subjectivity. Supervisors may differ greatly, and inevitably different decisions of entrustment will be made in similar situations. However, this is no reason to abandon expert judgment. As with clinical decision making, the experts need to do it, not the diagnostic assessment device. Of course, when evidence is available it should be used. And crucial decisions should be taken collectively among experts. In addition, we should develop assessment methods that include divergent expert judgment. The first steps on this path have been taken.20

Trust, competence, and qualification

In conclusion, the idea of trust reflects a dimension of competence that reaches further than observed ability. It includes the real outcome of training—that is, the quality of care. Supervisors who really trust a trainee to carry out a procedure that is critical for patient care involve themselves in the assessment process. Entrusting a critical activity should lead to the trainee being granted responsibility in all similar future circumstances. Once sound feedback has confirmed a critical number of times that all went well, the entrustment could be formalised and considered a qualification to act independently. It means that competence is present, as it is a prerequisite for the adequate execution of the activity.

The ideas I have elaborated need further investigation. But it is essential that innovation of postgraduate training should focus on expert appraisal of performance in practice and that trainees be qualified once they can be trusted to bear the responsibility for specific, entrustable, professional activities.

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors and sources: OtC was involved in the introduction of the CanMEDS model of competency based postgraduate training in 2004 in the Netherlands, as an adviser of the Dutch Central College of Medical Specialties. He currently advises specialty associations about reform of postgraduate medical training.

References

- 1.CanMEDS 2000 Project. Skills for the new millennium: report of the societal needs working group. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2005. www.healthcare.ubc.ca/residency/CanMEDS_2005_Framework.pdf (accessed 10 Apr 2006).

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Outcome project. www.acgme.org/Outcome (accessed 8 Aug 2006).

- 3.Bleker OP, Ten Cate ThJ, Holdrinet RSG. General competencies of the future medical specialist. Dutch J Med Educ 2004;23: 4-14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.General Medical Council. Principles of good medical education and training. London: GMC. www.gmc-uk.org/education/publications/gui_principles_final_1.0.pdf. (accessed 8 Aug 2006).

- 5.Australian Medical Association. AMA position statement prevocational medical education and training. www.ama.com.au/web.nsf/doc/WEEN-6JVTW2 (accessed 8 Aug 2006).

- 6.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990;65: 563-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rethans JJ, Norcini JJ, Baron-Maldonado M, Blackmore D, Jolly BC, LaDuca T, et al. The relationship between competence and performance: implications for assessing practice performance. Med Educ 2002; 36: 901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart A. Instructional design. In: Dent JA, Harden RM, eds. A practical guide for medical teachers. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2005: 186-93.

- 9.Carraccio C, Wolfsthal SD, Englander R, Ferentz K, Martin C. Shifting paradigms: from flexner to competencies. Acad Med 2002;77: 361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long DM. Competency-based residency training: the next advance in graduate medical education. Acad Med 2000;75: 1178-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant J. The incapacitating effects of competence: a critique. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 1999;4: 271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuwirth LWT, Van der Vleuten CPM. A plea for new psychometric models in educational assessment. Med Educ 2006;40: 296-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ 2005;39: 1176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flanagan JC. The critical incident technique. Psychol Bull 1954;51: 327-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey RJ. Job analysis. In: Dunnette MD, Hough L, eds. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Vol 2. 2nd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1991: 71-163. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonassen DH, Tessmer M, Hannum WH. Task analysis methods for instructional design. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999.

- 17.Wijnen-Meijer M, Ten Cate O, eds. A competency-based curriculum for society and health physicians. Utrecht: Collaborative Dutch Associations for Society and Health Physicians, 2006. [in Dutch].

- 18.Elstein AS, Shulman LS, Sprafk SA. Medical problem solving. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978.

- 19.Armstrong M. A handbook of human resource management practice. 10th ed. London: Kogan Page, 2006.

- 20.Charlin B, Roy L, Brailovsky C, Van der Vleuten C. From theory to clinical reasoning assessment. The script concordance test. Teach Learn Med 2000;12: 189-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]