Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can stimulate nitric oxide (NO•) production from the endothelium by transient activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). With continued or repeated exposure, NO• production is reduced, however. We investigated the early determinants of this decrease in NO• production. Following an initial H2O2 exposure, endothelial cells responded by increasing NO• production measured electrochemically. NO• concentrations peaked by 10 min with a slow reduction over 30 min. The decrease in NO• at 30 min was associated with a 2.7 fold increase O2•− production (p<0.05) and a 14 fold reduction of the eNOS cofactor, tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4, p<0.05). Used as a probe for endothelial dysfunction, the integrated NO• production over 30 min upon repeat H2O2 exposure was attenuated by 2.1 fold (p=0.03). Endothelial dysfunction could be prevented by BH4 cofactor supplementation, by scavenging O2•− or peroxynitrite (ONOO−), or by inhibiting the NADPH oxidase. Hydroxyl radical (•OH) scavenging did not have an effect. In summary, early H2O2-induced endothelial dysfunction was associated with a decreased BH4 level and increased O2•− production. Dysfunction required O2•−, ONOO−, or a functional NADPH oxidase. Repeated activation of the NADPH oxidase by ROS may act as a feed forward system to promote endothelial dysfunction.

Keywords: Nitric Oxide [D01.339.387], Hydrogen Peroxide [D01.248.497.158.685.750.424], Endothelium [A10.272.491], Nitric-Oxide Synthase [D08.811.682.135.772], Electrochemistry [H01.181.529.307]

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS: 1. BAECs - bovine aortic endothelial cells; 2. BH2 - 7, 8-dihydrobiopterin; 3. BH4 - tetrahydrobiopterin; 4. CMH - 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2, 2, 5, 5-tetramethylpyrrolidine; 5. ESR - electron spin resonance; 6. eNOS - endothelial nitric oxide synthase; 7. L-NAME - Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; 8. MAECs - mouse aortic endothelial cells; 9. PBS - phosphate buffered saline; 10. PEG-SOD - polyethelene glycol conjugated superoxide dismutase; 11. ROS - reactive oxygen species; 12. SOD - superoxide dismutase

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to contribute to cardiovascular disease, but some oxidative stress, such as that produced in moderate exercise, is associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease(1–3). One possible explanation for this apparent paradox is that small amounts or episodic exposures to ROS increase the oxidative buffering capacity of the body, while a larger amounts or repeated exposures overpower these compensatory mechanisms. The determinants of when compensatory mechanisms fail are unclear, however.

H2O2, most commonly produced when O2•− is dismutated by superoxide dismutase (SOD), is the most stable and long lasting of the ROS(4). It is likely to play a critical role in maintaining the balance between O2•− and NO•, since it has been shown to act as a signaling molecule for both NADPH oxidases and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). Presumably a compensatory response, exposure of endothelial cells to H2O2 causes upregulation of eNOS after several hours(5) and, on a shorter time scale (i.e., several minutes), activates eNOS through phosphorylation(6). On the other hand, continued exposure to H2O2 for an intermediate time period (30 min) results in reduced NO• bioavailibility(7). In addition, H2O2 activates the NADPH oxidases through phosphorylation of the NADPH oxidase subunit p47phox (4) to produce ROS, suggesting that continued or repeated ROS exposure may lead to reduced NO• by oxidation of BH4, an essential eNOS cofactor, resulting in dysfunctional, uncoupled eNOS(8). In these experiments, we tested the determinants of reduced NO• production upon continued H2O2 exposures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs; Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA) were cultured on 0.05% gelatin using M199 media (Cellgro, Herndon, VA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen-Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% of each of the following: penicillin/streptomycin (Cellgro), minimal essential media (MEM) vitamins (Cellgro), L-glutamine (Invitrogen-Gibco), and MEM Amino Acids (Invitrogen-Gibco). Experiments were performed at 37ºC on passage 4 or 5 cells that were 60–90% confluent. p47phox-knockout and wild type mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAECs) were isolated as described previously(9) and cultured on 0.1% gelatin in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Media (Invitrogen-Gibco) containing 1.25% MEM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen-Gibco), 12.5% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Norcross, GA), 2.5 U/mL heparin (Baxter, Deerfield, IL), and 2% endothelial cell growth serum (isolated from bovine brain extract). Experiments were performed at 37ºC on cells from passages 6–10 at 60–90% confluence.

NO• Measurement

NO• was measured using an NO•-specific carbon electrode. Nafion-coated carbon electrodes (100 μm exposed length x 30 μm diameter) were obtained commercially (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) and coated with o-phenylenediamine (o-PD) as described previously(6, 10–12). NO• was measured amperometrically against an AgCl reference electrode, with the voltage of the electrode held constant above the oxidation potential of NO• (+900 mV). Electrodes were calibrated with known concentrations of NO• (obtained by bubbling NO• through N2-degassed deionized H2O to saturation). To insure the faradic current represented only NO•, current seen in the presence of the eNOS inhibitor, L-NAME (Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester, 2 mM) was subtracted from the unprocessed current to give the L-NAME suppressible current used in all further analysis. In control experiments, the L-NAME suppressible current represented 79% of the total faradic current. All electrodes used showed linear calibration curves with R2 > 0.95.

Cell Treatments

Prior to experiments, cells were incubated in freshly made 60 μM BH4 for 10 min to compensate for variable cell culture-induced BH4 deficiencies(13–15). Experimental results in the absence of an initial BH4 supplementation were qualitatively identical but with lower NO• production, suggesting that pretreatment was not likely to affect the interpretation of the results. NO• measurements were made in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4, 37°C), with the electrode positioned with a micromanipulator 5 μm above the monolayer. With BH4 removed from the media to prevent any interaction with the electrode, cells were exposed to 50 μM H2O2, and the resulting increase in NO• production was measured for 30 min (“H2O2 exposure 1”). In order to probe the degree of endothelial dysfunction induced by this exposure, a second exposure was used. The same cells were then rinsed with PBS and again exposed to 50 μM H2O2 as the increase in NO• production was measured for 30 min (“H2O2 exposure 2”). The time between H2O2 exposures was limited to that necessary to change the media and was never more than 10 min.

To determine possible mediators of the reduced NO• production upon repeated H2O2 exposure, cells were pre-incubated for 30 min with apocynin (600 μM), O2•− scavenger polyethelene glycol conjugated superoxide dismutase (PEG-SOD) (450 U/mL), ONOO− scavenger uric acid (100 μM), or •OH scavenger mannitol (3 mM) prior to H2O2 exposure 1 or with 60 μM BH4 for 10 min prior to H2O2 exposure 2. While there is no specific scavenger of ONOO−, uric acid was chosen because it has minimal activity against O2•− and H2O2(16). To maximize the scavenger effects but prevent faradic contamination when measuring NO•, uric acid, mannitol, and apocynin treatments were extended into H2O2 exposure 1 but not into H2O2 exposure 2. All other treatments were terminated prior to H2O2 exposure 1 by washing the cells with PBS. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

Measurements of Biopterin Content

Measurements of biopterin content in BAECs were performed using HPLC analysis and a differential oxidation method as described previously(17). The amount of BH4 was determined from the difference between total (i.e., BH4, 7,8-dihydrobiopterin (BH2), and biopterin) and alkaline-stable oxidized biopterin (BH2 and biopterin). A Nucleosil C-18 column (4.6 x 250 mm, 5 μm) was used with 5% methanol/95% water as a solvent at a flow rate of 1.0 mL per min. The fluorescence detector was set at 350 nm for excitation and 450 nm for emission.

Measurements of Superoxide Production

All sample analyses were performed in pairs as previously described(18). The cell permeable spin probe 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine hydrochloride (CMH; Alexis Corp., San Diego, CA) was used to examine O2•− production using electron spin resonance spectroscopy (ESR). Cells treated as delineated above were washed twice with PBS, scraped from the plates, resuspended in 1 mL of PBS, and collected by centrifugation. Freshly isolated cells were allowed to equilibrate in deferoxamine-chelated Krebs-HEPES solution containing CMH (0.5 mM), deferoxamine (50 μM), and DETC (5 μM) for 90 min at 37°C. After the incubation period, a mixture containing 60% Krebs-HEPES buffer, 30% cell suspension, 10% CMH stock (2.4 mg/mL), with or without 2% SOD was transferred to a 100 μL capillary tube. Superoxide production by BAECs was detected by following the low-field peak of the nitroxide ESR spectra using a time scan with the following ESR settings: microwave frequency 9.78 GHz, modulation amplitude 2 G, microwave power 10 dB, conversion time 1.3 s, time constant 5.2 s. Analyses of the slopes of the time scans were used to quantify the amount of O2•− produced by the cells and compared to spectra in the presence of SOD. Superoxide production normalized for the total protein content was calculated as the difference in O2•− production in paired samples with and without SOD present.

Data Analysis

Current was obtained and analyzed using pClamp 8.0 (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Unprocessed currents were low-pass filtered using an 8-pole Bessel filter with 2 Hz cutoff frequency. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA), Graph pad Prism (Graph pad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA), or SPSS (Chicago, IL). NO• production as a function of time in response to H2O2 was compared using two-way ANOVAs. Multiple means were compared using one-way ANOVAs with post hoc testing for multiple comparisons or t tests with corrections for multiple comparisons as appropriate. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

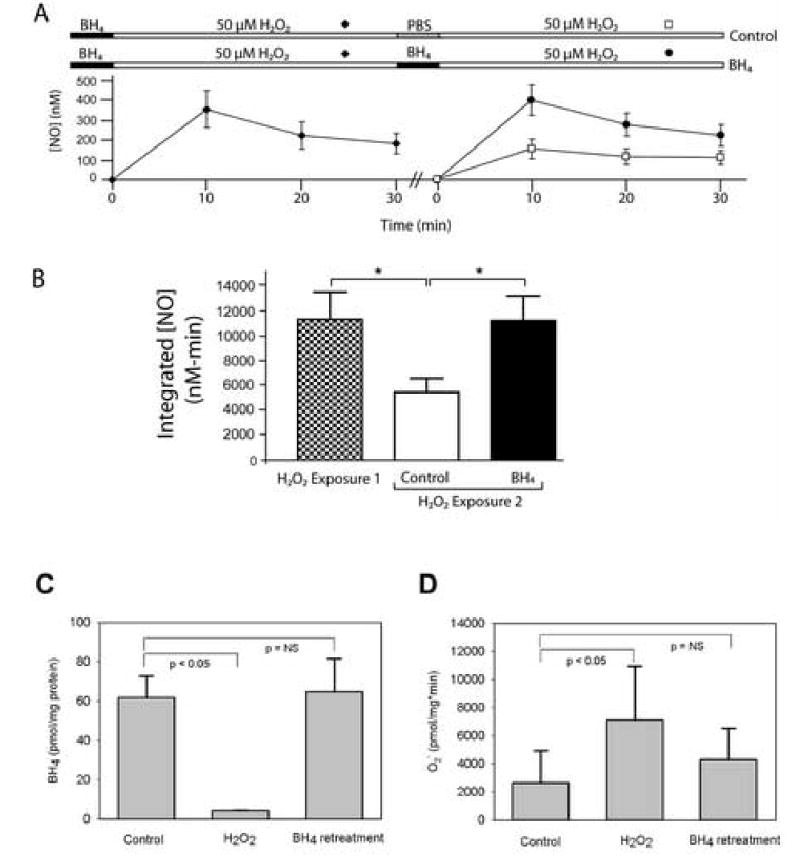

Previously, we have shown that exposure of endothelial cells to H2O2 results in a transient, immediate increase in eNOS-dependent NO• production(6, 12). Suggesting endothelial dysfunction, this presumably compensatory increase in NO• production began to decrease over 30 min of continued exposure (figure 1). After H2O2 exposure 1, the reduction in NO• production was associated with an increase in O2•− production and a decrease in cellular BH4 (figure 1, panels C and D). To quantify the degree of endothelial dysfunction induced, we used a second exposure to H2O2. After this second exposure, BAECs showed a reduction in peak and total NO• release when compared to the first exposure. Cells exposed to 50 μM H2O2 (H2O2 exposure 1) increased NO• production after 10 min to 356±94 nM (mean ± standard error mean, n=9). After 30 min, the NO• concentration decreased to 51.4% of the peak concentration. As an index of the total amount of NO• produced by cells, the integrated NO• signal over 30 min was 11261±2193 nM·min. After rinsing in PBS, the cells were again exposed to 50 μM H2O2 (H2O2 exposure 2). During H2O2 exposure 2, the peak NO• and the integrated NO• productions were reduced by 2.3- (p<0.05) and 2.0-fold (p<0.05) respectively when compared to that measured during H2O2 exposure 1.

Figure 1.

H2O2-induced endothelial dysfunction. Panel A: Following addition of H2O2 to BAECs, NO• production increases initial but then decreases over time (n=9). Demonstrating endothelial dysfunction, a second addition of H2O2 reveals a statistically smaller increase in NO• production (n=9; p<0.05). BH4 supplementation prior to rechallenging cells with H2O2 ameliorated the reduction in H2O2-induced NO• production (n=4). Panel B: BH4 supplementation prevents a reduction in NO• production between the first and second H2O2 exposures (p=0.7). Panel C: The reduction in NO• production after an initial 30 min H2O2 exposure was accompanied by a decrease in cell BH4 levels (p<0.05) that was completely corrected by BH4 supplementation. Panel D: The reduction in NO• production after an initial 30 min H2O2 exposure was accompanied also by an increase in O2•− production (p<0.05) that was corrected by BH4 supplementation.

The reduced NO• production was completely ameliorated by BH4 supplementation prior to the second H2O2 exposure. Comparing either the time courses of NO• production or the integrated NO• values indicated that NO• production from cells supplemented with BH4 just prior to H2O2 exposure 2 was not statistically different from the NO• production during H2O2 exposure 1 (p=0.4 and p=0.7, respectively). BH4 supplementation concomitantly reduced O2•− production and raised cellular BH4 levels to those seen before any H2O2 exposure (figure 1, panels C and D).

O2•− Scavenging and NADPH Oxidase Inhibition Prevented the Loss of NO• Production

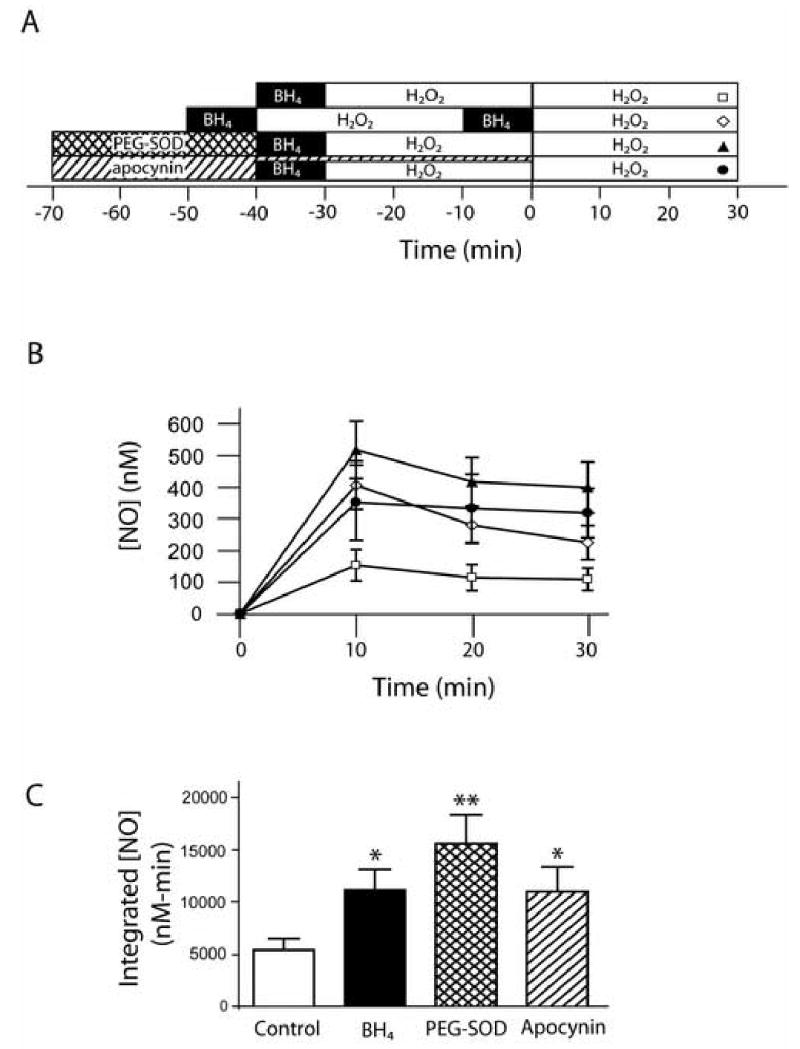

Because NADPH oxidases are activated by H2O2 and produce O2•− (19), we tested if H2O2-induced O2•− might contribute to the endothelial dysfunction observed. Treating cells with the cell permeable O2•− scavenger PEG-SOD prevented the decreased NO• production seen during the second H2O2 exposure (figure 2). This NO• production after a second exposure to H2O2 in PEG-SOD-treated cells was statistically improved when compared to a second exposure response in the absence of treatment (p<0.01) and was similar to that seen with a second BH4 supplementation treatment (p = 0.2). This result suggested that O2•− was causing the resultant dysfunction after repeat exposures to H2O2, possibly through BH4 oxidation.

Figure 2.

Superoxide scavenging and NADPH oxidase inhibition prevent the endothelial dysfunction. Panel A: Time courses of treatments. Panel B: Comparison of NO• production over time during the second H2O2 exposure with control (n=9, open squares), BH4 (n=4, open diamonds), PEG-SOD (n=4, filled triangles), and apocynin (n=4, filled circles) treatments. Panel C: Integrated NO• production over 30 min. BH4, PEG-SOD, and apocynin treatments were statistically different from control (* = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01) but not from each other (p=0.3).

Suggesting that the NADPH oxidase was required for the O2•−-mediated endothelial dysfunction seen, inhibiting NADPH oxidase assembly with apocynin (600 μM) prevented the dysfunction. A comparison of integrated NO• values indicated that the integrated NO• produced by apocynin was statistically different from the H2O2 control (p<0.05) and that apocynin, BH4, and PEG-SOD treatments resulted in indistinguishable salvage of NO• production as measured by a second H2O2 treatment (p=0.34 by one-way ANOVA).

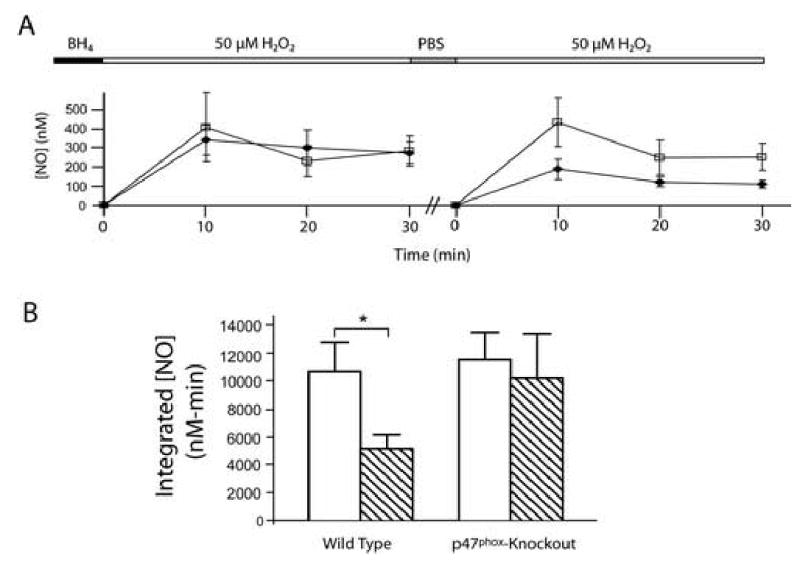

To support results seen with chemical inhibition of the NADPH oxidase, we repeated the experiments in aortic endothelial cells isolated from p47phox-knockout mice, which lack a critical subunit of the oxidase. Although there was a significant difference between the integrated H2O2 exposures 1 and 2 NO• productions in wild-type MAECs (p<0.05), NO• production was similar during both H2O2 exposures in p47phox-knockout cells (p=0.7). Integrated NO• production decreased 2.1 fold during the second exposure, an identical decease to that seen in BAECs. In p47phox-knockout cells, a second challenge with H2O2 caused a similar increase in NO• production (figure 3), eliminating the reduction seen in the wild-type cells.

Figure 3.

Endothelial dysfunction with H2O2 exposure is prevented in p47phox-knockout MAECs. Panel A: NO• production during subsequent H2O2 exposures was statistically different in wild-type cells (filled diamonds) but not in p47phox-knockout cells (open squares). Panel B: Integrated NO• production over 30 min in wild type and p47phox-knockout MAECs (H2O2 exposure 1, open bar, H2O2 exposure 2, diagonal stripes). Integrated NO• production was reduced with subsequent H2O2 exposures in wild type (* = p<0.05) but not in knockout cells (p=0.7).

ROS Scavengers Prevent the Loss of NO• Production with Repeated Exposures to H2O2

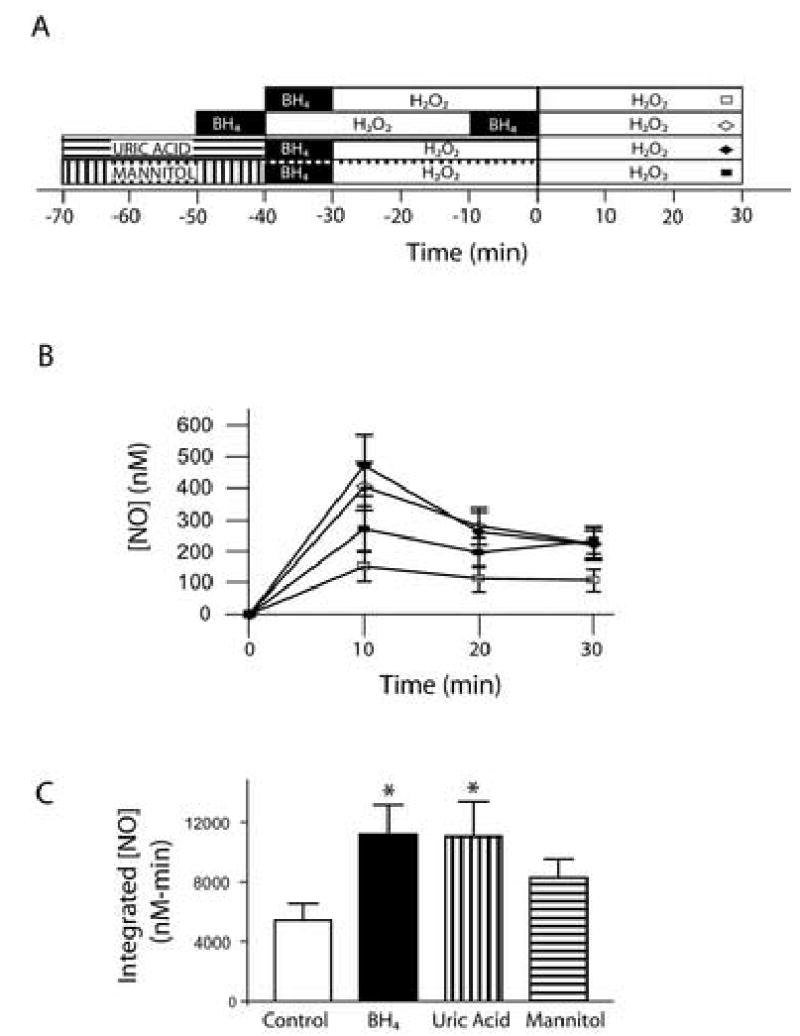

Production of O2•− also increases cellular levels of ONOO− and •OH, since ONOO− forms by reaction of O2•− with NO•, and •OH forms by degradation of protonated ONOO− or through the Haber-Weiss reaction(20, 21). BH4 is thought to be preferentially oxidized by these free radical species in comparison to O2•−(22). Therefore, we sought to determine whether these species were playing a role in the reduced NO• production seen with H2O2 exposure. Treating cells with the ONOO− scavenger, uric acid, prevented the endothelial dysfunction seen during the second exposure (figure 4). NO• production after uric acid was statistically indistinguishable from the effect of BH4 (p=0.96). Treating cells with the •OH scavenger, mannitol, did not have a significant effect (p>0.05), however.

Figure 4.

ONOO− but not •OH scavengers prevent endothelial dysfunction. Panel A: Time course of treatments with ONOO− scavenger uric acid (100 μM), •OH scavenger mannitol (3 mM), and H2O2 (50μM). Panel B: The time courses of NO• production during H2O2 exposure 2 for control (open squares, n=9), BH4 (open diamonds, n=4), uric acid (closed diamonds, n=4), and mannitol (closed squares, n=6) are shown. Panel C: Integrated NO• production over 30 min during H2O2 exposure 2 indicates that BH4, uric acid, and mannitol improve NO• bioavailability when compared to control cells. Uric acid treatment resulted in a statistically significant improvement from control (* = p<0.05) that was indistinguishable from that of BH4 (p=0.65). Mannitol did not improve statistically NO• bioavailability (p>0.05).

DISCUSSION

Many disease states are associated with decreased NO• and increased ROS, yet exposure to moderate levels of oxidative stress induces increased NO• production and production capacity(5, 6), presumably compensatory mechanisms. Therefore, it seems likely that some failure of these mechanisms is associated with the progression of disease. In this study, we explored early events leading to endothelial dysfunction during H2O2 exposure. We demonstrate that endothelial NO• production is increased acutely with exposure to H2O2 but that this production wanes with time and is reduced upon repeat exposure. This reduction in NO• is accompanied by decreased cellular BH4 and increased O2•− production, thought to be hallmarks of eNOS uncoupling. Supporting this possibility, the endothelial dysfunction observed during a second H2O2 exposure could be ameliorated with BH4 supplementation.

H2O2 activates not only eNOS but also the O2•−-producing NADPH oxidase(4). Furthermore, increased NADPH oxidase activity is associated with hypertension and progression of atherosclerosis, suggesting that this enzyme may be part of the pathogenic cascade that leads to uncompensated oxidative stress in these diseases(6). Therefore, we tested whether early H2O2-induced endothelial dysfunction could be mediated by the NADPH soxidase and its product, O2•−. Either genetic inhibition of the NADPH oxidase in p47phox-knockout cells or inhibition of the oxidase by apocynin resulted in a recovery of H2O2−induced NO• production to the level seen with BH4 supplementation, suggesting that the NADPH oxidase was an upstream mediator of the endothelial dysfunction seen.

Activation of the NADPH oxidase results in increased O2•−. Scavenging O2•− had effects on NO• production that were indistinguishable from apocynin or genetic inhibition of the oxidase. This implies that this ROS may be a downstream effector of NADPH oxidase activation. The trend toward increased NO• in PEG-SOD treated cells as compared to the cells with inhibited NADPH oxidase could be explained if additional protection from oxidative degradation of NO• was provided by scavenging oxygen radicals from other sources such as xanthine oxidase, cyclooxygenase, cytochrome P450, and mitochondria. Nevertheless, the majority of PEG-SOD effect could be attributed to dismutation of NADPH oxidase-produced O2•−.

Although O2•− can oxidize BH4, ONOO− and •OH are known to be more potent BH4 oxidizers(22–24). Because ONOO− is formed when O2• − and NO• react, scavenging of O2• − would indirectly prevent ONOO− formation. ONOO− scavenging with uric acid resulted in NO• production statistically similar to that if cells were supplemented a second time with BH4. Scavenging of •OH with mannitol did not result in recovery of NO• production, suggesting it is not important in the overall effect. Uric acid is not absolutely specific for ONOO−, however, but was chosen because of its minimal effects on O2• − and H2O2(16). The results with other ONOO agents such as Manganese (III) tetrakis (1-methyl-4-pyridyl)porphyrin pentachloride (MnTMPyP) would have been even more difficult to interpret in this case because of their effects on other ROS. Therefore, the most parsimonious interpretation of the scavenger data is that much of the endothelial dysfunction is mediated by the O2• − downstream product, ONOO−, but the involvement of other ROS cannot be rigorously excluded.

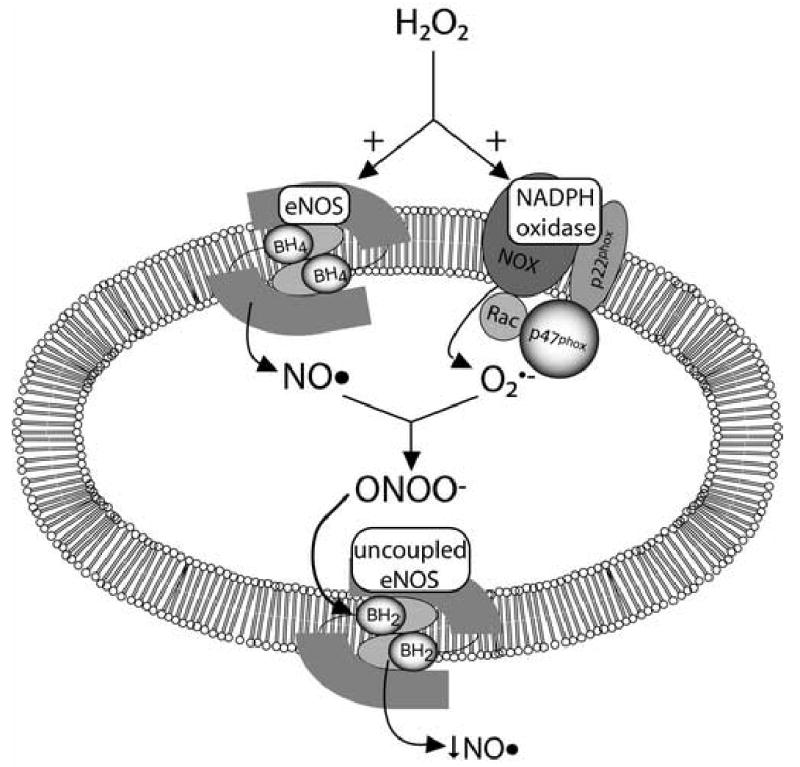

The simplest explanation for the NO• production profile seen upon H2O2 exposure involves activation of both eNOS and the NADPH oxidase. NADPH oxidase-derived O2• − reacts with NO• to form ONOO−. ONOO− reacts with BH4 to create uncoupled eNOS, resulting in a reduced NO• production in response to subsequent H2O2 exposures (figure 5). This hypothesis is supported by the similarity of BH4 supplementation with the effects of PEG-SOD, apocynin, and urate, suggesting that uncoupling of eNOS by BH4 oxidation is sufficient to explain the observed reduction in NO• produced with repeat H2O2 exposures. Alternatively, BH4 could be acting as a ROS scavenger. This possibility is less likely because BH4 has been shown to be an inefficient O2• − scavenger(25). Nevertheless, the possibility of ONOO− scavenging by BH4 cannot be eliminated.(15) In either case, the data support the fact that continued H2O2 exposure generates endothelial dysfunction and that this effect requires ROS production and NADPH oxidase activation.

Figure 5.

A unified hypothesis explaining the NO• production decrease in response to H2O2 exposure. Simultaneous activation of eNOS and the NADPH oxidase results in ONOO−. This species and possibly other ROS oxidize BH4 to BH2, causing uncoupling of eNOS. This reduces NO• measured on subsequent applications of H2O2.

BH4 oxidation in response to increased ROS may be part of the explanation for the failure of oxidative stress compensatory mechanisms during the time period studied. Moreover, this may explain the ability of BH4 to lower blood pressure in hypertensive mice,(26) if BH4 supplementation reduces uncoupled eNOS production and improves NO• bioavailability. Nevertheless, the effects of persistent oxidative stress are likely to be more complicated. Any effect of ROS to generate uncoupled eNOS may be exacerbated by dihydrofolate reductase downregulation(27), an enzyme that catalyzes reduction of oxidized dihydropterin to BH4, and counterbalanced by H2O2-induced BH4 production by GTP cyclohydrolase I (24).

In conclusion, although H2O2 caused an initial increase in NO• production, NO• levels declined over time with additional exposures to H2O2. The decline could be prevented by BH4 supplementation, scavengers of ROS, and NADPH oxidase inhibition. The similarity of these effects suggests that endothelial dysfunction with repeat H2O2 exposures could be explained by oxidation of BH4 by ONOO− produced when H2O2 activates both eNOS and NADPH oxidase. These findings may have implications for the progression of disease states associated with oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants, HL64828 and HL73753 (SCD), Department of Veterans Affairs Merit grant (SCD), and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award (SCD). Dr. Widder was supported by the Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina (BMBF-LPD 9901/8-97).

References

- 1.Kojda G, Cheng YC, Burchfield J, Harrison DG. Dysfunctional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression in response to exercise in mice lacking one eNOS gene. Circulation. 2001;103:2839–2844. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro A, Gomez C, Lopez-Cepero JM, Boveris A. Beneficial effects of moderate exercise on mice aging: survival, behavior, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial electron transfer. Am J Physiol. 2003;286:R505–R511. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00208.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Napoli C, Williams-Ignarro S, DeNigris F, Lerman LO, Rossi L, Guarino C, Mansueto G, DiTuoro F, Pignalosa O, DeRosa G, Sica V, Ignarro LJ. Long-term combined beneficial effects of physical training and metabolic treatment on atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8797–8802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402734101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai H, Griendling KK, Harrison DG. The vascular NAD(P)H oxidases as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:471–478. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drummond GR, Cai H, Davis ME, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression by hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res. 2000;86:347–354. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai H, Li Z, Davis ME, Kanner W, Harrison DG, Dudley SC., Jr Akt-dependent phosphorylation of serine 1179 and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 cooperatively mediate activation of the endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by hydrogen peroxide. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:325–331. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaimes EA, Sweeney C, Raij L. Effects of the reactive oxygen species hydrogen peroxide and hypochlorite on endothelial nitric oxide production. Hypertension. 2001;38:877–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: The role of oxidant stress. Circ Res. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang J, Saha A, Boo YC, Sorescu GP, McNally JS, Holland SM, Dikalov S, Giddens DP, Griendling KK, Harrison DG, Jo H. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates endothelial production of O2− from p47phox-dependent NAD(P)H oxidases, leading to monocyte adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47291–47298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedemann MN, Robinson SW, Gerhardt GA. o-Phenylenediamine-modified carbon fiber electrodes for the detection of nitric oxide. Anal Chem. 1996;68:2621–2628. doi: 10.1021/ac960093w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai H, Li Z, Goette A, Mera F, Honeycutt C, Feterik K, Wilcox JN, Dudley SC, Jr, Harrison DG, Langberg JJ. Downregulation of endocardial nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in atrial fibrillation: potential mechanisms for atrial thrombosis and stroke. Circulation. 2002;106:2854–2858. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039327.11661.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai H, Li Z, Dikalov S, Holland SM, Hwang J, Jo H, Dudley SC, Jr, Harrison DG. NAD(P)H oxidase-derived hydrogen peroxide mediates endothelial nitric oxide production in response to angiotensin II. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48311–48317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith AR, Visioli F, Hagen TM. Vitamin C matters: increased oxidative stress in cultured human aortic endothelial cells without supplemental ascorbic acid. FASEB J. 2002;16:1102–1104. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0825fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Channon KM. Tetrahydrobiopterin regulator of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:323–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzkaya N, Weissmann N, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22546–22554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuzkaya N, Weissmann N, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite with uric acid in the presence of ascorbate and thiols: implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukushima T, Nixon JC. Analysis of reduced forms of biopterin in biological tissues and fluids. Anal Biochem. 1980;102:176–188. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley SC, Jr, Hoch NE, McCann LA, Honeycutt C, Diamandopoulos L, Fukai T, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI, Langberg J. Atrial fibrillation increases production of superoxide by the left atrium and left atrial appendage: role of the NADPH and xanthine oxidases. Circulation. 2005;112:1266–1273. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.538108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Ushio-Fukai M. NAD(P)H oxidase: Role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res. 2000;86:494–501. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniyama Y, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species in the vasculature: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. Hypertension. 2003;42:1075–1081. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000100443.09293.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNaught AD, Wilkinson A, editors. Second Edition. Blackwell Science, Inc; Malden, MA: 1997. IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology: The Gold Book. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laursen JB, Somers M, Kurz S, McCann L, Warnholtz A, Freeman BA, Tarpey M, Fukai T, Harrison DG. Endothelial regulation of vasomotion in ApoE-deficient mice: Implications for interactions between peroxynitrite and tetrahydrobiopterin. Circulation. 2001;103:1282–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.9.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel KB, Stratford MRL, Wardman P, Everett SA. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin by biological radicals and scavenging of the trihydrobiopterin radical by ascorbate. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimizu S, Ishii M, Miyasaka Y, Wajima T, Negoro T, Hagiwara T, Kiuchi Y. Possible involvement of hydroxyl radical on the stimulation of tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis by hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite in vascular endothelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:864–875. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasquez-Vivar J, Whitsett J, Martasek P, Hogg N, Kalyanaraman B. Reaction of tetrahydrobiopterin with superoxide: EPR-kinetic analysis and characterization of the pteridine radical. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:975–985. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landmesser U, Dikalov S, Price SR, McCann L, Fukai T, Holland SM, Mitch WE, Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalupsky K, Cai H. Endothelial dihydrofolate reductase: Critical for nitric oxide bioavailability and role in angiotensin II uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:9056–9061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409594102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]