Introduction

One of the animating beliefs of British health service reformers in the first half of the twentieth century was that delivery would improve if greater co-ordination was imposed over disparate providers. The fundamental divisions were between the voluntary, public and private sectors. Voluntary provision predominantly meant acute care hospitals, but also included a range of other therapeutic and clinical services. The public sector delivered general practitioner (GP) services to insured workers through the state national health insurance (NHI) scheme, while the remit of local government covered environmental health, isolation and general hospitals and a wide range of personal services addressing tuberculosis, venereal diseases, mental illness, and maternity and child welfare. Finally, the private sector provided nursing homes and GP attendance at commercial rates.1 Within each area there were tendencies towards independent rather than co-operative working. Voluntary hospitals often lacked any mechanism for conferring with neighbouring institutions and the competitive logic of fund-raising enforced an individualistic ethic.2 In the public sector health responsibilities were dispersed across various agencies: local authority health committees, advised by the county or borough Medical Officer of Health (MOH), oversaw sanitation, hospitals and personal health services; education committees were responsible for the School Medical Service (SMS), whose remit was the compulsory medical inspection and treatment of elementary schoolchildren;3 the Poor Law provided institutional care either in workhouses or separate infirmaries, although after the 1929 Local Government Act the boards of guardians were broken up; their powers were then transferred to the public assistance committees of local authorities, however these remained distinct from health committees. GP services accessed through the state NHI system were overseen by local insurance committees separate from local government. Private practice co-existed with NHI and doctors tended to prioritize fee-paying rather than panel patients.4

A concern to rationalize this situation ran through policy documents from 1900, starting with the Minority Report of the Poor Law Commission (1909), which sought “unity of administration” to replace “wasteful and demoralising overlapping”.5 The Dawson Report of 1920 responded to its remit from government to consider “the systematical provision of … medical and allied services”, by proposing a scheme for primary health centres affiliated to secondary centres, which in turn were attached to teaching hospitals.6 The Cave Committee of 1921 also attacked the “lack of organisation and co-operation among the voluntary hospitals”, recommending local committees which would liaise with the Poor Law infirmaries to relieve waiting lists.7 Co-ordination within the public sector was central to the Local Government Act which sought to bring erstwhile Poor Law medical facilities under the control of health committees, while Section 13 of the Act called for joint voluntary/municipal hospital committees, giving statutory sanction to the collaboration which had failed to occur spontaneously. Shortly afterwards the non-governmental Sankey Report (1937) proposed regional co-ordination of voluntary hospitals “to bring their services into harmonious relationship” through joint fund-raising and planning.8

Despite all this exhortation, the prevailing wisdom at the outset of debates about creating a national health service was that little progress had been made. The PEP report (1937) described Britain's health services as “a mass of separate expedients … a bewildering variety of agencies, official and unofficial … created during the past two or three generations”, whose “general co-ordination … is still fragmentary”.9 The Cave and Sankey recommendations had not been met and the wartime hospital surveys of the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust concluded bluntly: “there is no hospital system now”.10 And the 1944 White Paper on the planned National Health Service (NHS), commenced with the observation that:

Many services are rendered by local authorities and others in special clinics and similar organisations … These are, for the most part, thoroughly good in themselves … But, owing to the way in which they have grown up piecemeal at different stages of history and under different statutory powers, they are usually conducted as quite separate and independent services…. [T]here has to be somewhere a new responsibility to relate them, if a service for health is to be given in future which will be not only comprehensive and reliable but also easy to obtain.11

Two questions arise from this. Why did the concern with an integrated service emerge, and why could this not be achieved within the mixed economy of inter-war medicine? Perhaps the most compelling theoretical framework for the impetus to co-ordination is that which foregrounds the impact of medical science. The period saw the advance of expertise closely linked to academic medicine, for example specialization in fields such as eyes, orthopaedics, skin, ear, nose and throat, facilities for laboratory analysis, departments of public health medicine and so on. Given the tendency for geographical concentration of such expertise in large university towns it was in the interests of both practitioners and public to ensure that an area's health services worked together to establish referral mechanisms and rationalize patient flows to appropriate institutions: “hierarchical regionalism” in Fox's phrase.12 Case studies of towns such as Sheffield, Manchester, Glasgow and Aberdeen have amplified this, identifying influential networks of members of public health departments, voluntary hospitals and medical schools who advanced integration through joint hospital committees.13 Work on individual cities and particular services has illustrated the joint activities of local government and voluntary sector in developing specialist work: contracting of laboratory and maternity services and of VD and infant welfare clinics, providing consultants in municipal hospitals, funding charities for the welfare of the blind and so on.14 A complementary reading stresses also the influence of the business model on health service organization.15 This period saw the advance of vertical integration of the firm, as mergers achieved economies of scale and fostered research and development. A “rationalization” movement championed “scientific management”, the school of thought derived from Taylorism, which encouraged systematic planning, managerial restructuring and the elimination of wasteful practices.16 Ernest Bevin summarized the implications thus: “In industry today … we are asked to rationalize. I would like to see the benefits of rationalization applied to the treatment of disease”.17 Finally, a cross-party enthusiasm for economic planning was discernible in the ideologically diverse advocacy groups which emerged in the 1930s, whether inspired by the Soviet command economy, or by the desire to avert recession.18

However the dynamic of integration cannot be understood solely as a value-neutral expression of technocratic advance. Instead the banner of “co-ordination” was raised by different interest groups seeking to advance their positions. Rather than regarding the NHS as the product of a consensus for reorganization, it may also be understood as the outcome of struggle which pitched the labour movement and progressive civil servants against the medical establishment.19 Resistance to change was expressed in the British Medical Association's (BMA) hostility to doctors coming under the authority of local government, and also by the limited advance of co-operative working between municipal and voluntary hospitals, while the left's growing enthusiasm for a state medical service, particularly as articulated by the Socialist Medical Association, represented a more radical vision.20 In this reading “co-ordination” to achieve a comprehensive and universal service was not just more efficient, it was profoundly ideological.

A Case Study: The Gloucestershire Extension of Medical Services Scheme

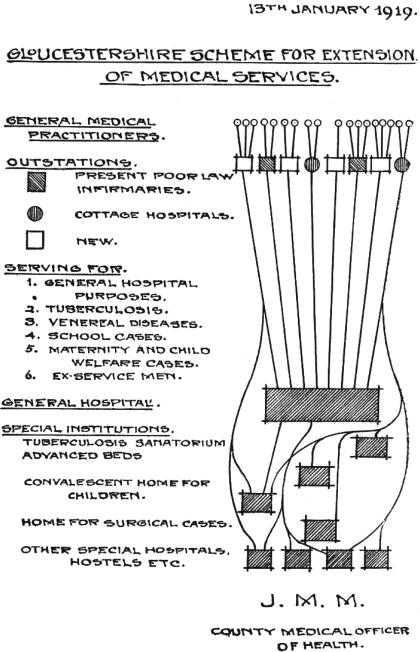

Thus far consideration of these issues has been at the level of national policy discourse, supported by a limited number of urban case studies. By contrast, the subject of this article is an initiative directed at the health of the rural population. This was a local experiment in service organization begun by Gloucestershire County Council in 1920, which sought in a novel way to integrate the work of GPs, the tax-funded public health services and the voluntary hospitals. Known as the Gloucestershire Extension of Medical Services Scheme (GEMSS), it was the brainchild of the County MOH, John Middleton Martin, and its innovative feature was the provision of “out-stations” in the rural parts of the county (Figure 1). These were small-scale health centres, either purpose built or situated in existing cottage hospitals, Poor Law institutions or tuberculosis dispensaries, and staffed by GPs paid on a contractual basis. Gloucestershire was divided into administrative areas (Bristol, Gloucester and Cheltenham), each with its general hospital, to which the out-stations were affiliated for patient referrals, and with its specialist institutions such as tuberculosis sanatoria.

Figure 1.

The scheme depicted as a referral network. (Source: Gloucestershire Archives, CM/R6, J Middleton Martin, Gloucestershire Scheme for the Extension of Medical Services (Gloucester, 1920); reproduced by kind permission of Gloucestershire Archives.)

The GEMSS differed from other municipal health services in several ways. First, it utilized independent GPs and consultants rather than local government medical officers. Second, its out-stations were all-purpose treatment centres, as opposed to clinics targeted at a particular population or ailment. Third, it imposed a referral network upon existing institutions—public and voluntary—to fulfil public health duties, rather than building a separate municipal network. Finally, it was managed, at least at its inception, by a committee consisting of local authority and voluntary hospital representatives.21 Here, apparently, was a concrete expression of the reformers' vision of service co-ordination, both between the municipal, private and voluntary sectors, and within the municipal sector, which proved so elusive nationally.

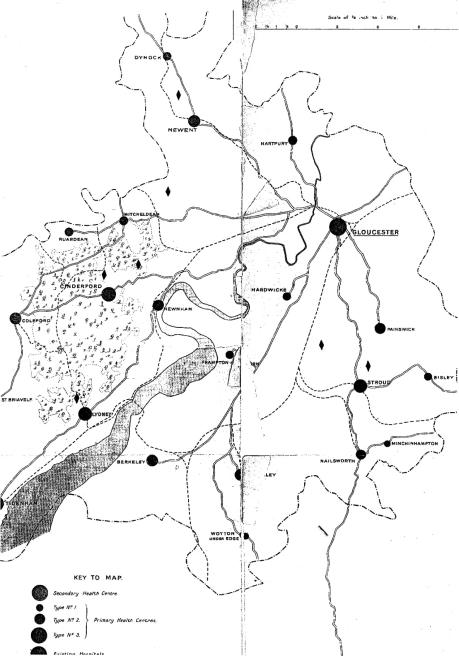

Indeed, the scheme was recognized both nationally and internationally, periodically attracting praise as a template that might be more widely applied. The Dawson Report reproduced a map of one of its regions (Figure 2), and argued that its own proposals for the integration of “primary” and “secondary” care “may be usefully illustrated by taking the actual example of Gloucestershire”.22 Arthur Newsholme's Milbank-sponsored study of European health systems accorded Gloucestershire a full chapter, suggesting that the scheme “furnishes valuable indications for other communities”.23 When the Ministry of Health conducted its public health surveys of local government in the early 1930s it too lauded the GEMSS's innovatory features, observing that it “deserves to be considered as a serious contribution to the theory and practice of public health in rural counties”.24 There was also American interest, in the visit of Professor Winslow of Yale University to study the out-stations, and the GEMSS's inclusion in a major study of British health insurance.25 The PEP report also detailed the arrangements, arguing that it demonstrated how “to bridge the gulf between official and unofficial health services which is so frequent and so unsatisfactory a feature of the present situation”.26 This then was an arrangement with more than just local interest, though as yet one which has attracted only passing mention from historians.27

Figure 2.

The scheme depicted in the Dawson Report. (Source: Consultative Council on Medical and Allied Services, Interim report on the future provision of medical and allied services, Cmd. 693, London, HMSO, 1920.)

The aim of this article is to treat the GEMSS as a case study which can illuminate two key questions about inter-war health services. First, by exploring the origin of the scheme, it seeks to identify the factors tending towards the regional co-ordination of inter-war health services. Second, in showing why the scheme remained of local and indeed diminishing significance, it will offer insight into the forces acting against the development of an organized health system based on a mixed economy, prior to the more far-reaching reforms of 1946–8. The principal methodology is a qualitative study of administrative documents generated by various committees of Gloucestershire County Council, along with the annual reports and publications of the Gloucestershire MOH. The reports also provide statistical details of the GEMSS which are used in conjunction with local tax data to survey its utilization and finances. Official responses to the GEMSS have been traced through consideration of the Dawson Report, of the Ministry of Health survey reports and correspondence, and the other documents noted above.

The Gloucestershire Extension of Medical Services Scheme: A History

Origin and Early Phase, 1918–1923

The Gloucestershire scheme had its formal inception in the county council's plans for the medical care of discharged servicemen. The idea of out-stations affiliated to general hospitals was mooted in April 1918, the context being a discussion of post-war treatment of disabled veterans prompted by the Ministry of Pensions.28 In early 1919 Middleton Martin secured approval from the Gloucestershire branch of the British Medical Association (BMA) and from one of the key voluntary hospitals, the Cheltenham General; the county council adopted the scheme in July 1919.29 A board of management, consisting of representatives of the local authority, the voluntary hospitals and the Red Cross, first met in October to plan the regional structure and submit formal proposals to the Ministry of Health; these were approved, initially for one year, in April 1920, at which point the scheme began.30

What were its main features at the time of conception? Middleton Martin's plan was to open out-stations throughout the county which would act as “a series of ‘forward’ out-patient departments for each hospital”.31 The ultimate goal was to provide fifty-six out-stations to cover the entire county: one within every three square miles.32 They were to be staffed by local medical practitioners who would attend at given times in the week, aided by district nurses, who would provide intermediate treatment in the doctor's absence. Specialist treatment would be delivered by consultants from the affiliated general hospitals, who would periodically visit out-stations to treat patients grouped according to a particular complaint. Payment for the doctors and nurses was at hourly rates, and the consultancy work contracted through a fixed annual sum paid to the designated hospitals.33 In addition to the management board, a medical advisory committee was organized, with GP, BMA and voluntary hospital representatives. This resolved questions over which doctors should serve at the out-stations and organized rotas where there was competition, so all shared in the benefits.34

With respect to finance, running costs were initially to be divided between the public health, education, and maternity and child welfare (MCW) committees of the council, and the local war pensions committee. A significant proportion of this would come not from the rates alone but from the Treasury grants which supported local authority tuberculosis, MCW and VD work. It was expected that the Exchequer would also finance much of the capital cost of the out-stations, subject to Ministry of Health approval. This was confidently anticipated, especially since the Red Cross had offered to grant £7,000 towards building costs if this was matched by government, leaving the council to find only £2,000 itself.35

The graphic (Figure 1) which accompanied a pamphlet written by Middleton Martin illustrates the expected chain relationship between out-stations, general hospitals and other specialist hospitals and services.36 The over-arching goal was to knit together the different health providers—voluntary, public and private—in a coherent hierarchical network for referrals and treatment. Health services would therefore reach groups in rural areas where distance, or, for children, parental commitments, meant that even where early diagnosis was made, follow-up treatment was lacking. Middleton Martin also stressed that this framework could be easily adapted to further co-ordination of existing services. In particular, he anticipated that the scope of NHI would be widened, and that the scheme's formalized referral system would replace the existing ad hoc arrangements, which relied upon the individual panel doctor's expertise and connections. In addition, he envisaged the removal from the Poor Law of the sick and infirm, who would also come under the scheme.37 Finally, he argued that the incipient hospital and medical insurance schemes for the middle class could also “readily be grafted on” to the GEMSS.38

The Intellectual Origins of the GEMSS

Where did the idea for the GEMSS come from? Given their apparently simultaneous gestation, it might be supposed that the Dawson Report provided the inspiration. However, according to Middleton Martin, his initiative predated Dawson's first public discussion of primary and secondary health centres. This was propounded in the Cavendish lectures of July 1918, three months after initial proposals in Gloucestershire.39 The Gloucestershire MOH subsequently corresponded with Dawson, whose biographer asserts that his support was instrumental in gaining approval for the scheme from the Ministry of Health, and in securing a pledge of financial aid from the Red Cross and the Order of St John.40 Dawson's significance may be overdrawn, since a prominent manager of GEMSS, Francis Colchester-Wemyss, was also a member of the Joint War Committee of the Red Cross.41 After publication of the Report, Middleton Martin initially distanced himself from Dawson's proposals when he perceived a negative response from the profession. The GEMSS out-stations, he stressed, were much more modest affairs than the primary centres proposed by Dawson, which conjured alarming images of salaried doctors in state polyclinics.42 However, he invoked Dawson in his support when addressing the BMA's Medical Sociology Section in 1921: the health services, he said, were “truly … at the parting of the ways”, and his scheme demonstrated how “to build up a constructive policy for the future”.43 Although he retained this rhetoric in later reviews of the scheme, he subsequently abandoned reference to Dawson.44 The evidence therefore suggests the Gloucestershire scheme was conceived independently of Dawson.

Despite the absence of direct influence, might Middleton Martin's thinking, like Dawson's, have been shaped by his wartime experiences?45 Certainly the proximate cause of the GEMSS's foundation was the anticipated need of the local war pensions committee. Such committees were empowered to provide appropriate care for veterans, with costs met by the Ministry of Pensions, and after the closure of the military hospitals in 1918 it was necessary to fund orthopaedic hospitals linked to out-patient facilities.46 Wartime structures also provided the model for the GEMSS's Medical Advisory Committee, whose constitutional procedures copied those of the Cheltenham War Hospital's advisory committee.47 In addition, the description of the out-stations as “ ‘forward’ out-patient departments for each hospital” is evocative of military language.48 That said, Middleton Martin, unlike Dawson, had remained on the home front, and reference to military medicine does not feature in any of the justifications proffered for his experiment.

Instead he presented the GEMSS essentially as a rational solution to the practical problems of meeting statutory health obligations in a rural locale.49 The choice, he asserted, was twofold. Either the council could employ specialist health officers and develop dedicated institutions to treat particular diseases or groups of patients, or it could build a service around private practitioners and existing institutions. The former method was appropriate in the county boroughs, but the counties had the problem of providing access to specialist care for patients in rural areas, for whom the distances involved in reaching municipal dispensaries and institutions were prohibitive. The archipelago of out-stations therefore promised to bring state medicine within easy proximity of all.

Did this apparently technocratic solution have an ideological foundation? Middleton Martin (Figure 3) certainly appears to have been a politically mainstream thinker. Born in Exeter in 1870 he took a first in natural sciences at Peterhouse, Cambridge, and gained his medical qualifications in London at University College Hospital. His career began as resident at Brighton's Hospital for Women, and he then studied for his Diploma in Public Health (1899) and MD (1903).50 His first public appointment (1901) was as MOH to the urban and rural district councils of Stroud and Nailsworth, areas of small-town textile industry and rural Cotswold parishes. He then became county MOH in 1903. After early research on the health of schoolchildren, he began to publish epidemiological studies, utilizing the relatively novel technique of correlating adjusted death rates from various diseases with environmental and economic variables.51 He was not afraid to adopt a maverick position on tuberculosis policy, arguing against the use of sanatoria on the grounds that the rate of decline in TB mortality was unrelated to trends in institutionalization. Instead his remedy was to improve early diagnosis, milk safety and nutrition to strengthen resistance; the Ministry of Health suspected that he used sanatorium admissions principally as a means of feeding underweight children.52 All this indicates that a first-hand experience of the needs of the rural poor underpinned the GEMSS project.

Figure 3.

John Middleton Martin. (Source: British Medical Journal, 13 Jan. 1940, i: 74, photograph by Elliot and Fry Ltd, reproduced with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group.)

Glimpses of his political perspective appear in his post-war publications on the organization of health services. He did not favour a more extensive state medical service, and was explicitly conservative in his preference for structures built around existing voluntary and private provision; one article invoked Polonius's advice to his son to make this point: “The friends thou hast and their adoption tried, grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel”.53 He was an active member of the local BMA, and also sat on several of its national bodies, including the Private Practice Committee.54 The problem of reconciling the interests of private practice and an expanding state medical sector was therefore a central concern. Indeed his thinking at the inception of the GEMSS may have been shaped by a salient national debate of 1917–18, over plans to extend the School Medical Service to include children in nursery and secondary schools. The BMA had objected that this foreshadowed the creation of a local authority medical service which would undermine private practice; hence the eventual legislation limited the right of local government to establish domiciliary services to undertake SMS work, and urged contracting from GPs instead.55 The out-stations concept, therefore, not only solved problems of rural isolation, but also systematized the co-existence of state and private medicine at a time when this relationship was controversial.

However, the real intellectual antecedents of the plan probably lay with the Majority and Minority Reports of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws (1909). The Commission embodied a new consensus over the need to reform Poor Law medicine, arising from the growing acceptance that disease was a cause of poverty, and that the stigmatizing and deterrent aspects of the Poor Law were harmful.56 Alternative remedies were proposed. The Minority Report strongly advocated the break-up of the Poor Law and the removal of its medical functions to council public health committees, providing services to which all would be entitled.57 Such a major advance of state medicine was rejected by the Majority Report, which recommended instead that medical care for the poor should remain with the remit of public assistance committees (who would replace boards of guardians). But, recognizing the need to strengthen the service, it called for a system of provident dispensaries which would serve both ordinary subscribers and Poor Law applicants, and be the nexus of integration with voluntary medical institution and private practice.58

Middleton Martin's proposals straddled these two positions. He explicitly cited the Majority Report's aspiration that its dispensary proposals would lead to the replacement of Poor Law medical officers by contracting from local practitioners.59 However his writings also invoke a sense of inexorable progress towards a health service which no longer discriminated against Poor Law patients. He identified a “gradual change in the social outlook, progressing with extraordinary rapidity” and a “general agreement … that the responsibility for the care of the poor should now be spread over a much wider area”.60 His conception of an escalating pace of change was expressed through narrative accounts of the Poor Law and public health statutes issued since the sixteenth century, viewed as “natural lines of progress” towards non-discriminatory public medical care.61 In this “gradual evolution of the problem of the care of the necessitous … the next stage would naturally be to provide care and treatment … avoiding the class distinction which is rightly regarded as very unfortunate”.62 To some extent social justice informed this thought, in the conviction that the divisiveness of the Poor Law and its accompanying stigma were anachronistic, and in the concern to provide rural dwellers with the “opportunities for which all pay”.63 However, rather than foreshadowing the expansive state medical service advocated by elements of the inter-war left—the health centre model of the Socialist Medical Association, for example—it looked back to New Liberalism, with its faith in organizational improvement to combat structural causes of social need.64

The Functioning of the Scheme 1920–48

Middleton Martin's bold plans were thwarted almost immediately. The Ministry of Health delayed its deliberations on the scheme, and approved the initial year only in early 1920, following lobbying by local MPs and by W F Hicks Beach, chair of both the county's public health committee and of the GEMSS, who also enlisted the support of George Newman, the Chief Medical Officer.65 This allowed an attenuated version of the scheme to commence, based on only eight out-stations. Then, in November 1921 the Ministry decided that it could not sanction further expansion. Nationally, the context was the post-war curb on expenditure for social reform, which has been variously explained in terms of bureaucratic failings, Conservative hostility and Treasury pressure.66 Further lobbying on behalf of the GEMSS ensued, but to no avail. By May 1922 the Ministry had confirmed its decision and the matching Red Cross funds were withdrawn.67 This financial blow coincided with a weakening of local support. One casualty was the plan for a comprehensive arrangement with the University of Bristol for pathological and bacteriological analysis, to be available for all practitioners. The county council voted instead to continue with its existing, and considerably cheaper, practice of limiting laboratory contracting to the council's own analytical requirements for specific diseases.68 Next it undermined Middleton Martin's own position, removing the £250 supplement to his annual salary for duties as the GEMSS's Executive Medical Officer.69

Worse was to follow when a hostile survey from the Board of Education criticized the administration of the scheme.70 The Board was the government department which oversaw the School Medical Service, and its sanction was required for the county education committee's expenditure on the GEMSS.71 Although the correspondence with the Board appears not to have survived, committee discussions reveal that its concern was with the GEMSS's costs, which had in practice fallen most heavily upon the education committee.72 Under the initial financing proposals, education was to provide one-third of the cost, commensurate with the anticipated proportion of the GEMSS's work which would be devoted to schoolchildren.73 In practice though, the education budget met 62 per cent of the cost in the first year (see Figure 6 below), rising to 77 per cent in the financial year 1922–23.74 The Board therefore demanded a restructuring of the management committee to allow the education committee nine of the eighteen seats, with the medical advisory committee (the doctors) reduced to consultative status.75 In addition to the reduction in Middleton Martin's salary, cuts were then made to consultants' fees and clerical support.76 In sum, the Ministry of Health's failure to back the scheme as it was originally conceived meant that it was a considerably scaled down version that was put into operation.

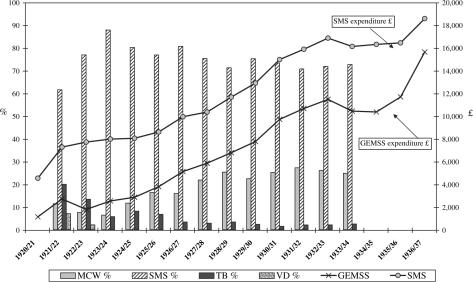

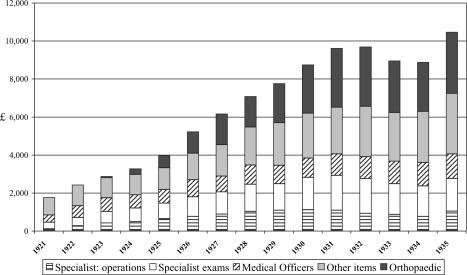

Figure 6.

Composition of the Gloucestershire Extension of Medical Services Scheme income and expenditure trends, 1920–37.

Following this inauspicious start, how did the scheme develop? Given the lack of capital the planned network of out-stations was drastically cut back and, despite gradual development, never reached the “ideal” coverage originally envisaged. In 1921, the first year for which statistical records appear in the annual report of Gloucestershire's MOH, eight out-stations were operational, and 911 attendances at these were recorded. By 1930 sixteen were in use, with just over 16,000 attendances, and by the time of Middleton Martin's retirement in 1937, the number had risen to eighteen.77 A map produced in 1932 shows seventeen operational out-stations, mostly in cottage hospitals but with a few purpose built in isolated districts (Bourton-on-the-Water, Chipping Campden).78 The standard design included waiting, consulting and dressing rooms, and lavatories; equipment was limited to cabinets for medicines and filing, weighing machines and eye test posters.79 In the mid-1930s some additional coverage was achieved by subsidiary out-stations, based in a room in the house of the district nurse.80 Two types of session were run. First, there were regular weekly openings at which the medical officer and district nurse examined and treated patients for minor ailments, typically referrals from the nurse or the School Medical Service. Second, hospital consultants attended for intermediate sessions to treat patients for ophthalmic, ENT, orthopaedic and tuberculosis complaints and rheumatic heart disease; surgical work performed at the out-stations was principally tonsils and adenoids operations.81 Two orthopaedic nurses also visited the stations as necessary to offer treatment such as massage, and oversee more routine work conducted by district nurses.82

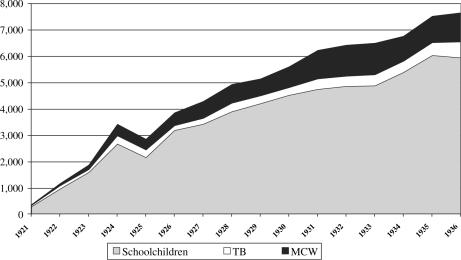

Figure 4 shows the main categories of cases treated. This demonstrates that the original aim of addressing a broad clientele ranging from war veterans to Poor Law patients was never fulfilled. Instead the main activity from the outset was dealing with schoolchildren. The fundamental achievement of the GEMSS was therefore the provision of a systematic referral system which ensured that the diagnostic work of school medical inspections was followed up by treatment, a situation which did not obtain in many areas.83 Tuberculosis work remained a fairly minor aspect of the scheme, and continued to be dealt with principally through the county's public health administration, overseen by the deputy MOH.84 In practice the scheme supplemented existing machinery by ensuring that country patients without easy access to urban dispensaries were seen regularly by the TB Officer.85 The same was true of maternity and child welfare work, where doctors acting as out-station medical officers were often also contracted by the MCW committee to run ante-natal and infant welfare clinics in isolated areas.86 Referrals were made where necessary to voluntary hospital consultants who made home visits in cases of puerperal pyrexia and difficult obstetrical cases, in 1932 five out-stations were equipped for dental work for expectant and nursing mothers.87 Finally, venereal disease work was a key area of growth in the 1930s, with some out-stations used as “VD sub-centres” at which the medical officer gave drug treatment, supervised by a Bristol VD specialist.88 This category of case was not counted in the annual statistics, so presumably numbers were small.

Figure 4.

Categories of cases treated under the Gloucestershire Extension of Medical Services Scheme, 1921–1936.

Figure 5 presents the main components of expenditure. About half of the costs went on medical personnel, to GPs for acting as out-station officers and to hospital consultants for attendances and surgical procedures. The “other items” category is not defined in the source material (the MOH annual reports) but presumably covers the rental costs for the out-stations, the maintenance fees of patients referred to hospital, and miscellanea such as clerical assistance and X-ray costs.89 Like the staff costs, these increased at a fairly stable rate as the activities of the scheme and the number of out-stations grew. The only component that markedly increased its share of spending was orthopaedics, which by 1931 accounted for about one-third of total expenditure. Prior to 1922 the only orthopaedic work done at public expense addressed “defects” due to tuberculosis, so this was a key innovation.90 In addition to the two nurses noted above, orthopaedic cases were grouped quarterly for examination at the out-stations and general hospital clinics, and where necessary home visits were organized following referrals by district nurses.91 Their work focused particularly on diseases of the foot (flat feet, club feet, claw feet), rickets (knock knees, bow legs), infantile paralysis and scoliosis.92 Orthopaedics costs were divided fairly evenly between the education and MCW committees, so again this was an aspect of the GEMSS's key function of advancing child health.93

Figure 5.

Composition of expenditure, Gloucestershire Extension of Medical Services Scheme, 1921–1935, current prices.

Turning finally to the financing of the scheme, Figure 6 shows the composition of its income (first y-axis, bars), which was drawn from four committees of the council.94 The education committee had a dominant role, providing on average 75 per cent of annual costs throughout the sequence. A growing proportion came from the MCW budget, illustrating the increasing focus on the pre-school child alongside the SMS work. The VD committee contributed only a minute sum after the first two years, and the amounts given by the TB committee also quickly declined as the GEMSS's tuberculosis work was predominantly aimed at schoolchildren. Total expenditure on the GEMSS (second y-axis, lines) is also shown, adjusted to constant prices to illustrate real trends; this is set against the total expenditure on public health from the School Medical Service budget (GEMSS, medical inspections, dental care). This shows, unsurprisingly, that the scope for the scheme's expansion was closely tied to the state of the education budget.

It is also important to stress that funding came from committees whose health work was heavily subsidized by central government. Under the percentage grant arrangement which obtained prior to 1930, MCW and TB work was supported at 50 per cent of approved expenditure, and VD treatment at 75 per cent.95 After 1930 councils received a block grant in support of rate and grant-borne expenditure, and, although this was not allocated to specific services, it may be assumed that it too underwrote health spending.96 Local education also received a Treasury grant, of at least 50 per cent, based on expenditure, average attendance and rateable values; the national mean was 55 per cent, while in Gloucestershire this averaged 60 per cent.97 It took the form of a block grant from which SMS costs were paid, although up until 1918–19 there had been a specific medical grant, which in its final year had covered 52 per cent of the school health budget.98 Thus, although the precise proportion of the GEMSS which was indirectly financed by the state is uncertain, it was at most only half funded from local rates. In part then its muted growth was due to the unwillingness of council members to authorize spending which would place any excess burden on the rates. To some extent this reflects the atmosphere of retrenchment which characterized inter-war municipal health services.99 However, in comparative perspective Gloucestershire seems to have been “a frugal minded body where public health is concerned”; the Ministry of Health noted disapprovingly in 1932 that the proportion of expenditure it committed to public health was lower than that of other southern agricultural counties.100

Muted Growth in the 1930s and 1940s

These statistical indicators of the GEMSS's performance confirm that, despite its achievements, Middleton Martin's vision was not fulfilled. Indeed the disappointments which followed the withdrawal of Ministry of Health support were accompanied by others. Public take-up was slow and initially capacity far exceeded demand.101 By 1922 the out-stations attached to the Stroud, Gloucester and Cheltenham hospitals were closed.102 The Ministry continued to be tight-fisted in its treatment, seeking to claw back the limited grants which it had made between 1920 and 1922 by offsetting these against the Red Cross grants.103 Growth was then restrained by financial retrenchment in the mid-1920s and the early 1930s: for example, plans in the 1931–2 estimates to increase the number of out-stations by seven were reduced to only two new buildings.104 The hoped for “grafting on” of NHI patients never occurred, and nor did the anticipated expansion of middle-class provident insurance take place.

None the less, the GEMSS did act as a modest integrating force. Joint working with Poor Law services progressed slightly, in the arrangement for Bristol surgeons to use Thornbury institution for tonsils and adenoids operations, and the opening of an out-station in Northleach Institution.105 The GEMSS also provided a channel for public funds to underpin voluntary hospital work, both through payments for services (initially through the generous block grant arrangement) and capital projects (architects' fees, building loans, etc.).106 Agreement was also reached to knit the GEMSS into the local hospitals’ contributory schemes, whereby contributors were excused user charges at municipal hospitals and paid reduced charges for their children.107 Another area of partial achievement was research. First, experimental treatment of parenchymatous goitre by iodine administration was trialled at various out-stations, though with inconclusive results. Second, there was a collaborative arrangement with Bristol University Centre of Cardiac Research, whereby children identified at the out-stations with signs of rheumatic heart disease were examined by specialists.108 Finally, there was a minor advance in joint working between cottage and general hospitals, with nurses from Lydney receiving training at Bristol Royal Infirmary.109

Perhaps the best opportunity to develop the scheme in a more substantial way was that presented by the Local Government Act. This provided for the transfer of the Poor Law from the boards of guardians to the council, and one aim was that the existing Poor Law medical services should be brought under health committees, rather than the public assistance committees, which now oversaw poor relief. In addition it was hoped that many of the old workhouse infirmaries would be “appropriated” by health committees and developed as municipal hospitals, free of the stigma of pauperism. None of this was mandatory, but was strongly desired by the Ministry of Health, in the interest of bringing all public medical services under the control of the MOHs. In the early 1930s Middleton Martin therefore hoped to realize his original vision of out-stations which provided “more general consultation services for insured persons, Public Assistance patients and the general public at modified fees”.110 In the event he was frustrated. He failed to assert the dominance of the MOH over county health services, and the public assistance committee continued to organize its medical services separately. Nor did he push strongly for transfer of the county's main public assistance institutions at Cheltenham, Tetbury and Thornbury to the control of the health committee. Instead he concentrated on a plan “to introduce … a system analogous to that under which the National Health Insurance service is worked”, whereby public assistance patients would be treated at out-stations “by any doctor willing to undertake the work on a capitation basis”.111 However, to his chagrin the council did not immediately decide to use the “machinery of the Treatment Scheme” for this purpose.112 After much delay and negotiation with the Ministry of Health, a small pilot scheme for Poor Law domiciliary relief in the Forest of Dean was finally put forward for ministerial approval.113 This however was turned down “on its administrative shortcomings” and, with his retirement now imminent, Middleton Martin abandoned the project.114

Under the new MOH, Kenneth Cowan, the scheme's history becomes more difficult to trace.115 From 1937 the annual MOH reports make no mention of the GEMSS, nor do they furnish statistics on its operation. Also, the management committee was downgraded to become a sub-committee of public health and housing, although the dominance of the education committee was ended by this restructuring.116 However, it continued to function much as before, achieving further internal rationalization when it took over the MCW committee's responsibilities for hospital treatment of under-fives.117 The out-stations and the orthopaedic schemes continued to operate, and a new orthoptic clinic was established at Bristol Eye Hospital. In 1939 Filton Health Centre in North Bristol was approved, to provide orthopaedic, dental, ante-natal and minor ailments clinics, a TB dispensary and a child welfare centre, though in the event the new centre was co-opted for war service as a first-aid post.118 By the 1940s then, the functions of the GEMSS were continuing, albeit disrupted by war, but it had effectively ceased to exist in name, disappearing with its progenitor, Middleton Martin.

Conclusion

The GEMSS was an imaginative plan which illustrates the scope for innovation afforded by the devolved health system of inter-war Britain. It was genuinely distinctive in four respects: the concept of general purpose out-stations went against the more typical practice of single-service clinics; its systematic outreach arrangements for rural areas were unusual; its reliance on private sector contracting contrasted with the standard municipal preference for public medical officers; and it offered a coherent and unique model of joint working premised on a hierarchical referral network. However, its ambitious conception was never realized. Despite the publicity which it generated, its practical achievement was very modest, and limited principally to the effective integration of the School Medical Service into the health system.

What light does this local example shed on the growth of support for regional integration? The explanation has stressed the importance of individual agency at the sub-national level, and Middleton Martin should be understood as one of the coterie of inter-war MOHs, such as John Buchan in Bradford, John Parlane Kinloch in Aberdeen and Robert Veitch Clark in Manchester, who attempted to innovate within the permissive framework of local government.119 Their efforts illustrate the capacity of mid-level civil servants to exploit existing legislation to develop new structures of social welfare. While there may have been a tendency towards self-interested “maximizing” of rewards in this (Middleton Martin's own salary proposals for instance), the motivation seems to have been largely pragmatic. The statistical and epidemiological analyses which were by now a requisite part of the MOH's toolkit exposed the dimensions of the problem, and practical experience suggested solutions.

However, there was also an ideological component, and here Middleton Martin represents different currents of contemporary thought. First, there was an implicit faith in the inexorability and rightness of the advance of state medicine: this was, as Arthur Newsholme later put it, “an essential condition … in a civilised community”.120 Second there were the conflicting visions of public medical provision articulated in the 1909 Majority and Minority Reports of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws. On the one hand there was the Minority Report's enthusiasm for medical relief provided through a unified local authority service, and on the other the Majority Report's belief that co-ordination through provident dispensaries and GP contracting was the optimal solution.121 It was the contradictions in these two routes to integration which the Gloucestershire scheme sought to reconcile, by establishing a publicly-funded, non-discriminatory service, yet at the same time circumscribing the growth of the state by employing private practitioners.

Finally, what does the relative failure of the GEMSS experiment reveal of the barriers to service integration within the mixed economy of inter-war medicine? First, the doctors themselves were not resistant to this model. State contracting of GP services was viewed favourably by the BMA, whose 1928 report on “encroachment” on private practice by local authorities had recommended acceptance of the growth of public specialist clinics, though staffed by part-time GPs; the advantages of this over full-time public health doctors were deemed to be the GPs' greater local knowledge and experience, their need to maintain reputation, and the benefits of drawing them into preventive and public health work.122 Gloucestershire doctors reached a similar conclusion in 1932 when a review of the GEMSS decided that there was no abuse of the system on financial or medical grounds; it found that since out-station medical officers were local GPs with a knowledge of their patients' circumstances there was little scope for better-off families to exploit the service.123

If the doctors were no barrier, the same could not be said for local or central government. Gloucestershire's reluctance to approve additional rate-borne expenditure to fund the GEMSS as initially envisaged is a reminder of the resource constraints affecting inter-war municipal medicine. Moreover, joint working between council committees did not prove straightforward, as departmental autonomy militated against the vision of co-ordinated services. When Middleton Martin complained that the education committee did not have “an instinctive alliance” with the health committee's goals, he was voicing a common complaint.124 Indeed similar turf wars had raged in Whitehall since 1914, when the Board of Education and the Local Government Board argued over responsibility for maternal education and infant welfare, then again in 1919 when the Board avoided surrendering its powers to the newly created Ministry of Health.125 The unwillingness of Gloucestershire's public assistance committee to bring the Poor Law medical service under the MOH's empire was also not untypical. Elsewhere too, the aspiration of unifying local services was thwarted by the permissive nature of the Local Government Act, as public assistance bodies (many of which included ex-guardians) proved reluctant to surrender their powers. This might be because they wished to retain the discriminatory ethos of the Poor Law, because they found the medical work satisfying, or because they worried about cost.126 Gloucestershire is illustrative of both ideological and temperamental impediments: the committee's policy had a “carry-on character”, due to its continuing “to view the situation through Poor Law spectacles”, while “the less the Medical Officer of Health and the Public Assistance Officer see of each other the better each is pleased”.127

Conceivably these difficulties might have been overcome with a strong lead from the centre, but government had been lukewarm from the first, when “owing to the sudden economy panic … the scheme was cut down by the Ministry of Health”.128 Why, though, was grant aid not forthcoming later, and the integration of public assistance work with the out-stations unsupported? Internal ministry correspondence suggests that civil servants had little enthusiasm for the GEMSS model, believing that the “general practitioner seldom makes a really satisfactory official”.129 Instead they preferred the gradual development of specialist services staffed by full-time public health officials answerable to the MOH. While it is arguable that this represented a consistent and justifiable policy, the failure even to explore alternative service delivery options is surely illustrative of the “insipid aspirations” of the inter-war Ministry of Health.130

The Gloucestershire scheme was an innovative project akin to the joint hospitals councils founded in major provincial cities. Such initiatives showed that a more comprehensive and equitable service might have been achievable through contracting mechanisms within the existing mix of public, voluntary and private provision. However, financial constraint, the permissive nature of central/local relations, and the lack of dynamic leadership from the Ministry of Health meant that best practice was not supported, nor extended. This left open the space for Aneurin Bevan's solution of a free and universal service established through a major advance of state medicine.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was funded by the Wellcome Trust. Earlier versions were presented at the ‘Municipal Medicine’ workshop, St Edmund's Hall, Oxford, 1–2 July 2004, and the Health History South West seminar, University of the West of England, 15 December 2004. I am grateful to participants and to this journal's anonymous referees for their helpful criticisms.

Footnotes

1 C Webster, The health services since the war. Volume I: Problems of health care, the National Health Service before 1957, London, HMSO, 1988, ch.1.

2 J Mohan, Planning, markets and hospitals, London, 2002, ch.3.

3 Political and Economic Planning (PEP), Report on the British health services, London, PEP, 1937, pp. 119–20. In theory co-ordination was effected through the MOH's role as titular head of both the health and school medical services, although relations were not always harmonious, see B Harris, The health of the schoolchild: a history of the school medical service in England and Wales, Buckingham, Open University Press, 1995, pp. 98–104; National Archives: Public Record Office (NA:PRO), ED 50/35, ‘Coordination between SMS and Public Health Staff’.

4 J Welshman, Municipal medicine: public health in twentieth-century Britain, Oxford, Peter Lang, 2000; M Powell, ‘An expanding service: municipal acute medicine in the 1930s’, Twentieth Century Br. Hist., 1997, 8 (3): 334–57; A Digby and N Bosanquet, ‘Doctors and patients in an era of national health insurance and private practice, 1913–1938’, Econ. Hist. Rev., n.s., 1998, 41 (1): 74–94, pp. 81–2, 90–1.

5 B Webb and S Webb (eds), The break-up of the Poor Law: being part one of the minority report of the Poor Law Commission, London, Longmans, Green, 1909, p. 584, paras 29, 30.

6 Consultative Council on Medical and Allied Services, Interim report on the future provision of medical and allied services (hereafter Dawson Report), Cmd. 693, London, HMSO, 1920, pp. 5–6.

7 Ministry of Health, Voluntary Hospitals Committee, final report, London, HMSO, 1921, Cmd. 1335, pp. 12–16.

8 British Hospitals Association, Report of the Voluntary Hospitals Commission, London, British Hospitals Association, 1937, pp. 9, 63–5.

9 PEP, op. cit., note 3 above, pp. 397, 413.

10 Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, The hospital surveys: the Domesday Book of the hospital services, Oxford, Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, 1946, p. 4.

11 Ministry of Health, Department of Health for Scotland, A national health service, Cmd. 6502, London, HMSO, 1944, pp. 7–8.

12 D Fox, Health policies, health politics: the British and American experience, 1911–1965, Princeton University Press, 1986, p. ix.

13 S Sturdy, ‘The political economy of scientific medicine: science, education and the transformation of medical practice in Sheffield, 1890–1922’, Med. Hist., 1992, 36: 125–59; J Pickstone, Medicine and industrial society, Manchester University Press, 1985, pp. 279–93; A Hull, ‘Hector's house: Sir Hector Hetherington and the academicization of Glasgow hospital medicine before the NHS’, Med. Hist., 2001, 45: 207–42; M Gorsky, ‘ “Threshold of a new era”: the development of an integrated hospital system in northeast Scotland, 1900–39’, Soc. Hist. Med., 2004, 17 (2): 247–67.

14 Welshman, op. cit., note 4 above, pp. 264–73; B Doyle, A history of hospitals in Middlesbrough, Gazette Media Company for South Tees Hospitals NHS Trust, 2003, pp. 13–14; G Phillips The blind in British society: charity, state, and community, c.1780–1930, Aldershot, Ashgate 2004, pp. 381–92, 400–5; L V Marks, Metropolitan maternity: maternal and infant welfare services in early twentieth century London, Amsterdam, Rodopi, 1996, pp. 177–91, 208–9, 214–23, 252–6.

15 S Sturdy and R Cooter, ‘Science, scientific management, and the transformation of medicine in Britain c.1870–1950’, Hist. Sci., 1998, 36: 421–66, pp. 425–30.

16 L Hannah, The rise of the corporate economy, London, Methuen, 1976, pp. 123–30, 139–40.

17 Hospital Saving Association, Annual report, 1929.

18 D Ritschel, The politics of planning: the debate on economic planning in Britain in the 1930s, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1997.

19 C Webster, ‘Conflict and consensus: explaining the British Health Service’, Twentieth Century Br. Hist., 1990, 1 (2): 115–51.

20 F Honigsbaum, The division in British medicine: a history of the separation of general practice from hospital care, 1911–1968, London, Kogan Page, 1979, ch.19; M Gorsky and J Mohan, ‘London's voluntary hospitals in the inter-war period: growth, transformation or crisis?’, Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 2001, 30 (2): 247–75, pp. 264–7; J Stewart, ‘The battle for health’: a political history of the Socialist Medical Association, 1930–51, Aldershot, Ashgate, 1999.

21 Gloucestershire County Council, Annual report of the Medical Officer of Health, 1936 (hereafter GCC MOH), Gloucester, 1937, p. 40.

22 Dawson Report, op. cit., note 6 above, p. 7.

23 A Newsholme, International studies on the relation between the private and official practice of medicine, 3 vols, London, Allen & Unwin, 1931–1932, vol. 3, ch. 16, p. 282; Newsholme was MOH for Brighton (1888–1908), then Medical Officer to the Local Government Board (1908–19), and was a strong advocate of comprehensive municipal medical services, see J M Eyler, Sir Arthur Newsholme and state medicine, 1885–1935, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 214.

24 NA:PRO MH66/90, A C Parsons, ‘Administrative County of Gloucestershire: report on a survey of health services’, p. 97.

25 Ibid., p. 90; D Orr and J Orr, Health insurance with medical care: the British experience, New York, Macmillan, 1938, pp. 140–2. Charles-Edward Amory Winslow was the chair of Yale's Department of Public Health (1915–45); around the time of the visit he was a member of the Committee on the Costs of Medical Care (1927–32), which examined international experience in its consideration of health services reform in the United States, and an expert health assessor (1927–30) of the League of Nations Health Organisation. See A J Viseltear, ‘C.-E. A. Winslow: his era and his contribution to medical care’, inC Rosenberg (ed.), Healing and history: essays for George Rosen, Folkestone, Dawson Science History Publications, 1979, pp. 205–28; I V Hiscock, ‘Charles-Edward Amory Winslow, February 4, 1877–January 8, 1957’, J. Bacteriol., 1957, 73 (3): pp. 295–6.

26 PEP, Report, op. cit., note 3 above, pp. 165, 256, 367–8, quote on p. 398.

27 Fox, op. cit., note 12 above, p. 60.

28 J Middleton Martin, Gloucestershire scheme for the extension of medical services, Gloucester, 1920, pp. 4, 6.

29 Ibid., p. 6.

30 Gloucestershire Archives (hereafter GA), CM/M/16/1 ‘Extension of Medical Services Board of Management Minute Book’ (hereafter GEMSS MB), 25 Oct. 1919, 24 April 1920.

31 ‘Extension of institutional medical services’, Br. med. J., 22 Feb. 1919, i: 218–19, p. 218.

32 J Middleton Martin, ‘The problem of medical services’, Contemp. Rev., 1922: 364–72, on p. 369; Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, p. 94.

33 Middleton Martin, ibid., p. 371.

34 GA, CJ/M/16/1 GEMSS MB, 14 July 1920; NA:PRO MH/66/ 91 ‘Appendix 6’, pp. 3, 5.

35 GA, CM/M/16/1/ GEMSS MB, 21 June 1919.

36 Middleton Martin, Gloucestershire scheme, op. cit., note 28 above, p. 7.

37 GCC MOH 1924, p. 33.

38 Middleton Martin, ‘The problem of medical services’, op. cit., note 32 above, p. 369; idem, ‘The medical profession and rate-provided hospitals’, Br. med. J., 6 Aug. 1921, ii: 191–2.

39 Middleton Martin, Gloucestershire scheme, op. cit, note 28 above, p. 6; Br. med. J., 1918, ii: 23–6, 56–9; intriguingly Dawson and Middleton Martin both trained at University College London, though Dawson was six years the elder: C Webster, ‘The metamorphosis of Dawson of Penn’, in Dorothy Porter and Roy Porter (eds), Doctors, politics and society: historical essays, Amsterdam, Rodopi, 1993, pp. 212–28.

40 F Watson, Dawson of Penn, London, Chatto and Windus, 1950, pp. 155–6.

41 Who was who 1951–60, London, Adam & Charles Black, 1967, p. 227.

42 ‘Correspondence’, Br. med. J., 27 Nov. 1920, ii: 842; 11 Dec. 1920, p. 916; 18 Dec. 1920, p. 952; Honigsbaum, op. cit., note 20 above, pp. 64–133.

43 Br. med. J., 6 Aug. 1921, ii: 191–2, on p. 191.

44 GCC MOH, passim.

45 Webster, op. cit., note 39 above, pp. 213–16; Sturdy and Cooter, op. cit., note 15 above, pp. 433–4.

46 Ministry of Pensions, First annual report of the Minister of Pensions to 31st March 1918, London, HMSO, 1919, pp. 4–11, 30–1, 36–7; Second annual report of the Minister of Pensions from 31st March 1918 to 31st May 1919, London, HMSO, 1920, pp. 26–7.

47 Newsholme, op. cit., note 23 above, pp. 311–12.

48 ‘Extension of institutional medical services’, Br. med. J., 22 Feb. 1919, i: 218.

49 Middleton Martin, ‘The problem of medical services’, op. cit., note 32 above, pp. 367–8.

50 The Medical Directory 1934, London, J & A Churchill, 1934, p. 975.

51 J Middleton Martin, ‘An analysis of Gloucestershire statistics, 1901–10’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, Section of Epidemiology and State Medicine, 1915–16, 9: 1–32; idem, ‘Scarlet fever outbreak at Stroud due to milk’, Public Health, Dec. 1901, 14: 138–42; idem, ‘Schools and infectious disease’, Public Health, July 1902, 14: 608–11; idem, ‘An inquiry into the distribution of certain diseases (cancer, phthisis, and pneumonia) on the western slopes of the Cotteswold Hills’, Public Health, Oct. 1904, 17: 4–31; Eyler, op. cit., note 23 above, pp. 27–41.

52 J Middleton Martin, ‘Tuberculosis—dogmas and doubts of sixty years’, Br. med. J., Feb. 1939, i: 204–9; Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, pp. 71–3.

53 Middleton Martin, ‘The problem of medical services’, op. cit., note 32 above, p. 372.

54 ‘Obituary’, Lancet, 20 Jan. 1940, i: 149; ‘Obituary’, Br. med. J., 13 Jan. 1940, i: 74.

55 Harris, op. cit., note 3 above, pp. 81–2.

56 J Middleton Martin, ‘Poor law reform and public health’, Br. med. J., 28 Aug. 1926, ii: 376–80, on pp. 378–9; Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress (hereafter Majority Report), 5 vols, Cd. 4499, 1909, vol. 1, pp. 371–2, 380–1.

57 Webb and Webb (eds), op. cit., note 5 above, pp. 585–7; though authored by Beatrice Webb, these recommendations were informed by Arthur Newsholme, whose pioneering organizational work as MOH for Brighton must have been familiar to Middleton Martin from his contemporaneous stint in the city, Eyler, op. cit., note 23 above, pp. 165, 195–219; A M McBriar, An Edwardian mixed doubles, the Bosanquets versus the Webbs, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1987, pp. 231–6, 297–8.

58 Majority Report, pp. 384–8; S Sturdy, ‘Alternative publics: the development of government policy on personal health care, 1905–11’, in S Sturdy (ed.), Medicine, health and the public sphere in Britain, 1600–2000, London, Routledge, 2002, pp. 241–59.

59 Majority Report, pp. 358–9; Middleton Martin, ‘Poor Law reform’, op. cit., note 56 above, pp. 378–9.

60 Middleton Martin, ibid., p. 377.

61 Middleton Martin, ‘The problem of medical services’, op. cit., note 32 above, pp. 364–7; idem, ‘Poor Law reform’, op. cit., note 56 above, pp. 376–8.

62 Middleton Martin, ‘Poor Law reform’, op. cit., note 56 above, p. 380.

63 J Middleton Martin, ‘The medical profession and rate-provided hospitals’, Br. med. J., 6 Aug. 1921, ii: 191–2, on p. 191.

64 Stewart, op. cit., note 20 above; J Harris, Private lives, public spirit: Britain 1870–1914, Oxford University Press, 1993; Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1994, pp. 237–41.

65 GA, CM/M/16/1 GEMSS MB, 20 Dec. 1919, 27 March 1920, 24 April 1920.

66 B Harris, The origins of the British welfare state: society, state and social welfare in England and Wales, 1800–1945, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2004, pp. 180–1.

67 GA, CM/M/16/1 GEMSS MB, 10 Oct. 1921, 1 May 1922; CM/M1/4 ‘Public Health and Housing Committee’, 26 Nov. 1921.

68 GA, CM/M/16/1 GEMSS MB, 21 June 1920, 11 Dec. 1920, 12 March 1921; GCC MOH 1936, Gloucester, 1937, p. 56.

69 GA, CM/M/16/1 GEMSS MB, 26 Nov. 1921, 24 June 1922.

70 GA, CM/M/16/1 GEMSS MB, 13 Oct. 1922.

71 Gloucestershire County Council report of the Education Committee for 1922–23 (hereafter GCC EC), p. 32.

72 GA, CM/1 Gloucestershire Education Committee, signed copies of Minutes, May 1921 to March 1923, inclusive, vol. lxv, 25 Nov. 1922.

73 GCC EC, 1921–22, p. 33.

74 Gloucestershire County Council, Abstract of accounts, 1921–22, 1922–23 (hereafter GCC Abstract).

75 GA, CJ/M/8/1 GEMSS MB, 21 April 1923; CM/M1/4, ‘Public Health and Housing Committee’, 24 March 1923; CC/MS Gloucestershire County Council, minutes of proceeding, xxxv, 10th April, 1923 to 18th February 1924, 9 July 1923.

76 GA, CJ/M/8/1 GEMSS MB, 21 April, 7 July, 5 Aug. 1923.

77 GCC MOH, 1921, 1930, 1936.

78 Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, insert after p. 93.

79 NA:PRO MH/66/ 91, ‘Appendix 6’, p. 7.

80 Ibid., p. 9; GCC MOH 1933, p. 28.

81 NA:PRO MH/66/ 91, ‘Appendix 6’, pp. 10–11.

82 Ibid., p. 5; GCC MOH 1933, p. 32.

83 Harris, The health of the schoolchild, op. cit., note 3 above, pp. 110–13.

84 U.K. Local Government Financial Statistics, 1935–36.

85 Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, p. 91.

86 Ibid., p. 96.

87 NA:PRO MH/66/ 91, ‘Appendix 6’, p. 14; GCC MOH 1932, p. 32.

88 NA:PRO MH/66/92, L Harrison, ‘Gloucestershire VD Scheme’, 9 July 1934.

89 NA:PRO MH/66/ 91, ‘Appendix 6’, p. 4.

90 GCC MOH 1932, p. 32; this was a national trend, see Harris, Health of the schoolchild, op. cit., note 3 above, pp. 110–11.

91 GCC MOH 1932, p. 31.

92 GCC MOH 1934, p. 35.

93 GA, CJ/M/8/7 GEMSS MB, 2 Dec. 1929.

94 GCC, Abstract, passim; composition of income was reported only for the years shown; from 1934–5 the GEMSS element was not disaggregated from the total school medical service contribution to public health.

95 H Finer, English local government, London, Methuen, 1946, pp. 464–5.

96 City and county of Bristol: epitome and general statistics of the city accounts for the year ended 31st March 1932, Bristol, 1932, pp. 6–7.

97 Finer, op. cit., note 95 above, p. 462; Harris, Health of the schoolchild, op. cit., note 3 above, p. 92.

98 GCC, Abstract, 1918–19.

99 Welshman, op. cit., note 4 above, pp. 135, 176, 181, 258–9.

100 Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, pp. 5, 8; the comparison was made with Cornwall, Shropshire, Berkshire, West Sussex, Bedford, Dorset, Devon, Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire.

101 GCC MOH 1921, p. 41.

102 GA, CM/M/16/1 GEMSS MB, 1 May 1922.

103 GA, CJ/M/8/1 GEMSS MB, 6 Oct. 1923.

104 NA:PRO MH/66/ 91, ‘Appendix 6’, p. 9.

105 GA, CJ/M/8/1GEMSS MB, 8 Sept. 1923; CJ/M/8/8 GEMSS MB, 5 Oct. 1931.

106 GA, CJ/M/8/4 GEMSS MB, 4 Sept., 4 Dec. 1926; CJ/M/8/8 GEMSS MB, 5 Dec. 1932; CJ/M/8/12 GEMSS MB, 7 June 1934, 4 March 1935.

107 GA, CJ/M/8/11 GEMSS MB, 6 Nov. 1933.

108 Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, p. 91; GCC MOH 1929, p. 31.

109 GCC MOH 1933, p. 27.

110 Ibid., p. 27.

111 Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, pp.189, 191–2.

112 GCC MOH 1932, p. 30.

113 NA:PRO MH 66/92 ‘Gloucestershire CC Post survey’, ‘Annex to 664/4201/2’, 2 Feb. 1934; ‘Previous history of the services transferred from the Guardians’, n.d. 1936.

114 Ibid., ‘Previous history’; and ‘Post survey’, ‘Gloucestershire County Council’ 2 March 1937, typescript of meeting.

115 Cowan went on to be MOH for Essex County Council, 1949–54, then Chief Medical Officer to the Scottish Department of Health, 1954–64, Who was who, 1971–1980, London, Adam & Charles Black, 1981, p. 177.

116 GA, CJ/M/8/15 GEMSS MB.

117 GA, CJ/M/8/15 GEMSS MB, 3 Jan. 1938.

118 Ibid., 5 July 1937; GA, CJ/M8/17 GEMSS MB, 4 Sept. 1939, 29 April 1940.

119 T Willis, ‘The Bradford Municipal Hospital experiment of 1920: the emergence of the mixed economy in hospital provision in inter-war Britain’, in M Gorsky and S Sheard (eds), Financing medicine: the British experience since 1750, London, Routledge, 2006; Gorsky, op. cit., note 13 above; Pickstone, op. cit., note 13 above, pp. 276–83.

120 Sir A Newsholme, Medicine and the state: the relation between the private and official practice of medicine with special reference to public health, London, 1932, p. 29; for Newsholme, see notes 23 and 57 above.

121 Sturdy (ed.), op. cit., note 58 above, pp. 242–9.

122 ‘Interim report on encroachments on the sphere of private practice by the activities of local authorities’, Br. med. J., Supplement, Nov. 1928, pp. 185–95, esp. paras 16, 17.

123 GA, CJ/M/8/10 GEMSS MB, 7 Nov. 1932.

124 Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, p. 27.

125 Eyler, op. cit., note 23 above, pp. 324–33; Harris, Health of the schoolchild, op. cit., note 3 above, pp. 98–102.

126 Fifteenth annual report of the Ministry of Health, Cmd. 4664, PP 1933–34, XII 265, pp. 45–54.

127 Parsons, op. cit., note 24 above, pp. 127, 189–90, 200.

128 GCC MOH 1929, p. 30.

129 NA:PRO MH 66/90 Minute Sheet, 24 Dec. 1932, H MacEwen to Wrigley.

130 W A Robson, The development of local government, London, Allen & Unwin, 1954, pp. 194–5, cited in Welshman, op. cit., note 4 above, p. 253; Eyler, op. cit., note 23 above, pp. 387–8.