Guus Rimmelzwaan and colleagues1 have contributed extremely valuable knowledge through their paper in this issue of the American Journal of Pathology regarding the ability of the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus to replicate in domestic cats.1 Using a traditional pathogenesis approach and relatively simple techniques from the pathologist’s armamentarium, they have made substantive contributions to understanding aspects of the disease in humans.

Through immunohistochemistry using a monoclonal antibody to influenza A nucleoprotein, Rimmelzwaan et al1 demonstrate that there is extensive extrarespiratory spread of the H5N1 virus in a mammalian (feline) host, with involvement of a number of tissues, including nervous, cardiovascular, urinary, digestive, lymphoid, and endocrine systems. They also demonstrated the ability of the cats to excrete H5N1 virus in feces. The authors postulate that spread from one animal to another could occur via three different potential excretory pathways—respiratory, digestive, or urinary tract. The finding of routes of excretion is particularly noteworthy and calls for vigilant biosecurity surrounding human cases.

Pathological investigations of disease due to H5N1 in humans have been limited. First, the available material is often not truly representative because it presents only an end-stage of the process and is usually altered by treatment and/or secondary invaders. Second, there are numerous cultural issues that preclude the performance of autopsies in some of those countries that have experienced the largest number of cases, and so the availability of postmortem material for investigation is limited.2 Consequently, this paper sheds considerable light on what might be happening in infected humans and should help clinicians as they strive to develop the most appropriate therapies.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza has become the “zoonosis” of the decade and hopefully will not become the pandemic of the century. The term “zoonosis” was coined by the German physician Rudolf Virchow exactly 150 years ago, while he was working on the public health issues of trichinosis and alveolar hydatid disease. On the subject of comparative medicine, Virchow stated, “Between animal and human medicine, there is no dividing line—nor should there be.”3 Virchow is a name familiar to all pathologists because he is widely regarded as the father of modern pathology and is heralded for elucidating the cellular nature of disease, which drastically changed the course of medicine. However, it may be his emphasis on considering diseases across species lines that will be his most lasting legacy.

Guus Rimmelzwaan and colleagues remind us that the call to one medicine is more relevant today than ever. Human health and animal health are inextricably intertwined, with a steady parade of emerging zoonotic problems over the last 25 years, beginning with human immunodeficiency virus moving from an African primate to humans, creating the most critical new infectious problem facing human health in our generation. Subsequently, there have been a myriad of microbial zoonotic agents surfacing in humans: prions in beef finding their way to neurons in human teenagers; West Nile virus from Israeli geese crossing continents to cause human and equine mortalities in North America; monkeypox virus in African giant rats infecting North American prairie dogs, which then carried the virus into living rooms and human beings in four U.S. states; and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus descending from bats to civet cats to a human super spreader who shared it with fellow travelers from four different continents at a hotel in Hong Kong.4 And now, avian influenza is making an inexorable march across Asia into Europe, infecting not only expected avian hosts but also potentially cats and people. The interface of human and animal health has become very blurred, and adequate public health measures for zoonotic disease control require an understanding of husbandry and ecology in the animal host.

Although most influenza pandemics in history are now known to have arisen through reassortment of avian and human viruses, the ability of avian viruses to directly infect humans was not regarded as a significant danger until recently.5 Within the past 8 years, there have been many detections of avian influenza virus in humans, with four different subtypes. Beginning with the death of a three-year-old boy in Hong Kong in May of 1997, there has been a steady string of incidents involving human illness and death due to various highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses contracted from poultry, first in Hong Kong and China, then in the Netherlands, subsequently in Canada, and now, most frighteningly, in Southeast Asia.

Background on Avian Influenza

Avian influenza (AI) viruses are very widespread in nature and have been isolated from more than 90 different species of free-living birds. Wild birds, especially shorebirds, ducks, and geese, are regarded as the natural reservoir of all AI viruses, with intestinal cells from these species displaying a receptor that is particularly attractive for AI viruses.6,7

Most strains of AI are of low pathogenicity and do not pose a significant problem for birds. These low virulence viruses have the type of hemagglutinin glycoprotein precursor that can be cleaved only by trypsin or trypsin-like enzymes. Consequently, replication is restricted to respiratory and intestinal tracts, where these enzymes can be found. Infection of poultry with these low virulent strains may be associated with mild respiratory signs, depression, and decrease in egg production. Occasionally secondary bacterial invaders will create a more critical disease situation. In contrast, the virulent viruses, termed “highly pathogenic avian influenza” (HPAI) have an hemagglutinin glycoprotein that can be cleaved by a ubiquitous protease, perhaps furin, that is found in virtually all organs.8 So, the virulent viruses are not restricted to replication in only the respiratory or intestinal tract but, once within the systemic circulation, have access to all tissues and organs. Pathogenesis studies in chickens have documented this phenomenon. Using immunohistochemistry, it has been shown that the HPAI viruses replicate in endothelial cells throughout the body, with spillover to adjacent parenchymal cells in numerous organs. Depending on the virulence of the strain, death can be peracute without clinical signs or may present with pulmonary, cardiac, or neurological involvement.9–11 Thus, it has been recognized for some time that the HPAI viruses are capable of extrapulmonary spread in chickens. Documenting similar distributions in a mammalian host, done by Rimmelzwaan et al1 in this issue of the American Journal of Pathology, extends the comparative pathology to what is most likely happening in humans.

Highly pathogenic avian influenza infections are often introduced into poultry operations through the presence of wild birds or their feces.12 Intermingling at outdoor ponds or inadequate biosecurity at poultry facilities has been responsible for outbreaks in many places. Consequently, control is most challenging in situations with limited biosecurity such as small farms and backyard flocks, exactly the type of husbandry situations most prevalent in developing countries, which are also the nations most challenged with maintaining sufficient animal health infrastructure to diagnose and contain the disease when it occurs.

Challenges of HPAI Control

Some of the issues surfacing as a result of HPAI involve agriculture, and both human and veterinary health scientists would benefit by increased awareness of changes and issues at the interface of agriculture and human health. Some of these issues are detailed below.

Globalization and Agriculture

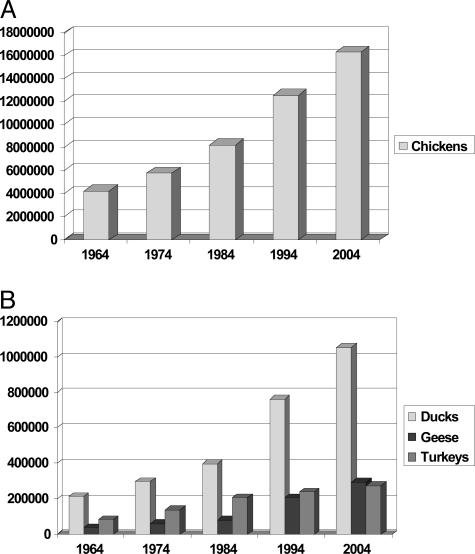

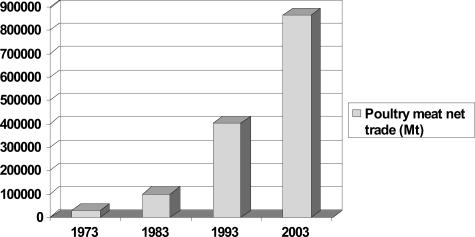

Globalization has radically altered the distribution and dissemination of trade products in the world. Agriculture is one of the most globalized industries, and poultry is the fastest growing segment of global agriculture. Of the 26 billion animals raised to feed the 6.2 billion people in the world last year, over 16 billion were chickens. Figure 1, A and B, demonstrates the dramatic increases in chicken and duck production over the last 40 years. Figure 2 demonstrates the 20-fold increase in chicken exports that has occurred over the last 30 years. In 2003, 868,000 metric tons of poultry meat was exported from one country to another, representing a 20-fold increase over the last 30 years. Who says chickens don’t fly?

Figure 1.

Numbers of poultry produced globally, in thousands, 1964–2004. Numbers of chicken (A) and non-chicken poultry (B). Source for numerical data: FAO Statistical Databases (http://faostat.fao.org/, accessed September 12, 2005).

Figure 2.

International trade in poultry meat, in metric tons, 1973–2003. Source for numerical data: FAO Statistical Databases (http://faostat.fao.org/, accessed September 12, 2005).

Concentration of Production in Agriculture

The necessity for efficiency to produce the animal protein needed to feed the world requires a concentration of animals. This move to agribusiness has been especially dramatic in the poultry sector, where it is now a reality that often as many as 10 million birds are raised within a few square kilometers.13,14 When disease enters, this concentration allows for tremendous amplification of the infectious agent, not to mention problems with control and eradication. If you consider the potential for amplification within the large facilities and the likelihood for introduction to or maintenance in the bio-insecure smallholder facility that may be nearby, the possibility for large-scale disaster has increased considerably.

International Transparency

Highly pathogenic avian influenza is a disease of significant economic importance to the poultry industry, because when HPAI enters a country, the poultry become worthless on the export market. For lesser developed countries that often rely heavily on revenue from agriculture, the temptation to deal with the disease without notifying international authorities is especially strong. Increasing transparency is paramount in controlling spread of this dangerous pathogen.

Public Health and Animal Health Need Common Understanding

Perhaps the brightest spot in the global HPAI situation has been the collaboration of all of the relevant scientists and regulatory entities involved in both agriculture and public health. The repeated gatherings of the World Organization for Animal Health, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the World Health Organization to discuss control and containment methodologies are reassuring, because it has become apparent that control of the disease in the human sector will require control of the disease in animals. Virchow’s admonition to consider disease in a comparative framework, “Between animal and human medicine there is no dividing line… ,” was prescient for his time. Today it is our reality, as Rimmelzwaan et al have demonstrated.1 Continued collaborations in realms beyond avian influenza could further ensure enhanced health protection for all species.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge very helpful suggestions from my valued colleague Dr. David Swayne.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Corrie Brown, Department of Veterinary Pathology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7388. E-mail: corbrown@vet.uga.edu.

This commentary relates to Rimmelzwaan et al, Am J Pathol 2005, 168:176–183, published in this issue.

Related article on page 176

References

- Rimmelzwaan GF, van Riel D, Baars M, Bestebroer TM, van Amerongen G, Fouchier RAM, Osterhaus ADME, Kuiken T. Influenza A virus (H5N1) infection in cats causes systemic disease with potential novel routes of virus spread within and between hosts. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:176–183. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normile D. Vietnam battles bird flu … and critics. Science. 2005;309:368–373. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5733.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauder JV. Interrelations of human and veterinary medicine. N Engl J Med. 1958;258:170–177. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195801232580405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Shi Z, Yu M, Ren W, Smith C, Epstein JH, Wang H, Crameri G, Hu Z, Zhang H, Zhang J, McEachern J, Field H, Daszak P, Eaton BT, Zhang W, Wang LF. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayne DE. Understanding the ecology and epidemiology of avian influenza viruses: implications for zoonotic potential. Brown C, Bolin C, editors. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology Press; Emerging Diseases of Animals. 2000:pp. 101–130. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DJ. A review of avian influenza. Proceedings of the European Society for Veterinary Virology (ESVV) Symposium on Influenza Viruses of Wild and Domestic Animals, Ghent, Belgium, 16–18 May 1999. Vet Microbiol. 2000;74:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford JS. Influenza A pandemics of the 20th century with special reference to 1918: virology, pathology and epidemiology. Rev Med Virol. 2000;10:119–113. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(200003/04)10:2<119::aid-rmv272>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinke-Grober A, Vey M, Angliker H, Shaw E, Thomas G, Roberts C, Klenk HD, Garten W. Influenza virus hemagglutinin with multibasic cleavage site is activated by furin, a subtilisin-like endoprotease. EMBO J. 1992;11:2407–2414. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CC, Olander HJ, Senne DA. A pathogenesis study of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N2 in chickens, using immunohistochemistry. J Comp Pathol. 1992;107:341–348. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(92)90009-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins LEL, Swayne DE. Varied pathogenicity of a Hong Kong-origin H5N1 avian influenza virus in four passerine species and budgerigars. Vet Pathol. 2003;40:14–24. doi: 10.1354/vp.40-1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins LEL, Swayne DE. Comparative susceptibility of selected avian and mammalian species to a Hong Kong origin H5N1 high-pathogenicity avian influenza virus. Avian Dis. 2003;47:956–957. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086-47.s3.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M, Crawford JM, Latimer JW, RiveraCruz E, Perdue ML. Heterogeneity in the haemagglutinin gene and emergence of the highly pathogenic phenotype among recent H5N2 avian influenza viruses from Mexico. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1493–1504. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-7-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatwright S, McKissick J: 2004 Georgia Farm Gate Value Report, University of Georgia. http://www.caed.uga.edu/staffreports_files/2004%20Farm%20Gate%20Value%20Report.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Capua I, Alexander DJ. Avian influenza: recent developments. Avian Pathol. 2004;33:393–404. doi: 10.1080/03079450410001724085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]