Abstract

The Stt4 phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase has been shown to generate a pool of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P) at the plasma membrane, critical for actin cytoskeleton organization and cell viability. To further understand the essential role of Stt4-mediated PI4P production, we performed a genetic screen using the stt4ts mutation to identify candidate regulators and effectors of PI4P. From this analysis, we identified several genes that have been previously implicated in lipid metabolism. In particular, we observed synthetic lethality when both sphingolipid and PI4P synthesis were modestly diminished. Consistent with these data, we show that the previously characterized phosphoinositide effectors, Slm1 and Slm2, which regulate actin organization, are also necessary for normal sphingolipid metabolism, at least in part through regulation of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin, which binds directly to both proteins. Additionally, we identify Isc1, an inositol phosphosphingolipid phospholipase C, as an additional target of Slm1 and Slm2 negative regulation. Together, our data suggest that Slm1 and Slm2 define a molecular link between phosphoinositide and sphingolipid signaling and thereby regulate actin cytoskeleton organization.

Cellular membranes consist of lipid bilayers that typically contain a complex set of different phospholipids. In addition to providing structural support and functioning in membrane fluidity, phospholipids also play a role in cellular signaling through their ability to recruit various effector proteins. The inositol-containing phospholipids, known as phosphoinositides, are exceptionally well suited for this function, since modification of their inositol headgroup can serve to promote membrane targeting of specific effector molecules. These recruited proteins often contain domains (i.e., PH, PX, FYVE, or ENTH, etc.) that bind with high affinity to a particular phosphorylated derivative of phosphatidylinositol (PI) (22). Therefore, changes in phosphorylation of the inositol headgroup, through the action of kinases and phosphatases, can serve to activate or terminate signaling pathways initiated by different effectors. Importantly, phosphoinositides have been implicated in a number of different cellular processes, including actin organization, vesicle trafficking, and cell proliferation, demonstrating their fundamental significance in diverse areas of cell biology (33).

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been a useful system for studying the roles for phosphoinositides, since several of the PI kinases, PI phosphatases, and effectors are well conserved (28). For example, PI 3-phosphate (PI3P), whose production in yeast is mediated by the Vps34 PI 3-kinase, functions in membrane trafficking in multiple species. Similarly the role of PI 4,5-biphosphate (PI4,5P2), generated by the yeast Mss4 PI4P 5-kinase, in actin organization and endocytosis is well characterized in multiple cell types (33). However, the function of PI4P is less well understood. In yeast, two essential PI 4-kinases, Stt4 and Pik1, function to generate independent pools of PI4P that are each required for cell viability (2, 11, 41). Recently studies have indicated a role for Pik1-generated PI4P at the Golgi in secretion, while Stt4 generated PI4P at the plasma membrane appears to function in actin organization and cell integrity (1, 2, 16, 38). However, genetic studies have also suggested roles for Stt4 in phospholipid metabolism (36), a yeast cell cycle checkpoint, and mitotic exit (40). Additionally, it remains unclear whether the role for Stt4-generated PI4P in actin organization is direct or through its role as a precursor to PI4,5P2 production.

In addition to phosphoinositides, sphingolipids and their precursors, sphingoid bases and ceramide, have also been shown to function in actin cytoskeleton organization and endocytosis (9). Specifically, loss of the serine palmitoyltransferase Lcb1, which catalyzes the first step in sphingolipid synthesis, results in a defect in actin polarization (43). Further study identified the sphingoid base phytosphingosine as a direct activator of Pkh1 and Pkh2, homologs of mammalian phosphoinositide dependent kinase PDK1, which are also required for actin organization (13). Additionally, overexpression of Pkc1, an effector of Pkh1 and Pkh2 that regulates actin organization, could rescue the phenotypes exhibited by loss of Lcb1 function (14). However, it remains to be shown how sphingoid base-dependent activation of Pkc1 ultimately controls actin organization.

Interestingly, previous work has suggested a role for phosphoinositides in sphingolipid metabolism, suggesting that these distinct lipids may function together (4). Using cells lacking Csg2, an enzyme normally required for production of the sphingolipid mannosylinositolphosphoceramide (MIPC), a screen was performed to isolate mutations that allowed cells to grow on media containing excess calcium (4). Unlike wild-type cells, csg2Δ cells fail to grow in the presence of 100 mM calcium (5). Several suppressors were isolated and further characterized, including a mutant form of Mss4. However, the mechanism behind this suppression has not been examined further.

In this study, we used synthetic genetic array (SGA) analysis to further investigate the role of Stt4, combining the stt4ts mutation with the set of 4,700 viable yeast deletion mutations. Surprisingly, we found that stt4ts cells could not tolerate perturbations in long chain fatty acid elongation, which is important for normal sphingolipid biosynthesis. Moreover, we show that the Stt4- and Mss4-mediated phosphoinositide production is required for heat shock-induced sphingolipid synthesis and that the PI4,5P2 binding proteins, Slm1 and Slm2, also function in this pathway. Loss of Slm1 and Slm2 function has been shown to result in a defect in actin organization (3), which we now demonstrate can be suppressed either through the inactivation of calcineurin, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase, or loss of the inositol phosphosphingolipid phospholipase C Isc1, both of which alter inositolphosphoceramide (IPC) metabolism. Together, these data suggest that Slm1 and Slm2 mediate cross talk between two major lipid signaling pathways that both respond to cellular stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

Enzymes used for recombinant DNA techniques were used as recommended by the manufacturer. Standard recombinant DNA techniques and yeast genetic methods were performed, and the growth media used have been described elsewhere (15, 25). Transformation into yeast was performed by a standard lithium acetate method (17). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are described in Table 1. All gene disruptions and temperature-sensitive mutant strains were generated similarly, as described previously (1). Integrated epitope tagging was performed as described previously (24). SGA analysis was performed as described previously (35). The strain expressing the temperature-conditional allele, aur1-19, was generated similar to that described using error-prone PCR (1).

TABLE 1.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| SEY6210 | MATα leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 | 29a |

| SEY6210.1 | MATaleu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-Δ200 trp1-Δ901 lys2-801 suc2-Δ9 | 29a |

| AAY102 | SEY6210 str4Δ::HIS3 carrying pRS415str4-4 (LEU2 CEN6 str4-4) | 2 |

| AAY202 | SEY6210 mss4Δ::HIS3MX6 carrying Ycplacmss4-102 (LEU2 CEN6 mss4-102) | 32a |

| AAY608 | SEY6210 rho1Δ::URA3 carrying pRS316rhoI | 1 |

| AAY603 | SEY6210 pkc1Δ::LEU2 carrying Ycp50pkc1-2 | 1 |

| AAY2007 | SEY6210 tor2Δ::HIS3 carrying pRS415tor2-1 (LEU2 CEN6 tor2-1) | This study |

| AAY1191 | SEY6210 fen1Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| AAY1192 | SEY6210 sur4Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| AAY1208 | SEY6210 csg2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| AAY1602 | SEY6210 slm1Δ::HIS3 | 3 |

| AAY1610 | SEY6210 slm2Δ::HIS3 | 3 |

| AAY1622 | SEY6120 slm1Δ::HIS3 slm2Δ::HIS3 carrying pRS415slm1-1 (LEU2 CEN6 slm1-1) | 3 |

| MTY203 | SEY6210 cnb1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| MTY155 | SEY6210 aur1Δ::HIS3MX6 carrying pRS415aur1-19 | This study |

| AAY1212 | AAY102 csg2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| AAY1213 | AAY202 csg2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MTY111 | AAY603 csg2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MTY174 | MTY155 csg2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MTY369 | AAY1602 csg2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MTY379 | AAY1610 csg2Δ::HIS3 | This study |

| MTY236 | SEY6210 isc1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| MTY365 | AAY1622 cnb1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| MTY248 | AAY1622 isc1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| MTY261 | AAY1622 cnb1Δ::HIS3MX6 isc1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| MTY256 | MTY369 isc1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| MTY387 | MTY369 cnb1Δ::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| MTY200 | AAY102 aur1Δ::HIS3MX6 carrying pRS414aur1-19 | This study |

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation.

Cell labeling and immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (1, 2, 15). For phosphorylation analysis of Slm1, cells were grown in YNB medium with the appropriate amino acids to log phase, harvested, and labeled with 20 μl Tran 35S label (per unit of optical density at 600 nm; DuPont New England Nuclear) for 10 min. Cells were chased with an excess of unlabeled methionine/cysteine for the indicated times, and proteins were precipitated with 9% trichloroacetic acid on ice. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with antisera against green fluorescent protein (GFP; a kind gift from C. Zuker, UCSD). Immunoprecipitated proteins were resuspended in sample buffer, resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and subjected to autoradiography. Treatment with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and immunoprecipitation with antiserum against GFP have been described previously (3).

Sphingolipid analysis.

Before labeling, cells were grown in YNB medium with the appropriate amino acids. For short pulse-chase labeling experiments, log-phase cells were harvested and then shifted to the appropriate temperature for 10 min, followed by the addition of 20 μCi of [3H]serine (Nycomed Amersham, Princeton, NJ). After 80 min, cells were lysed in 4.5% perchloric acid with glass beads to generate extracts. The extracts were subjected to centrifugation for 20 min, and the pellets were washed once with 100 mM EDTA. The perchloric acid-precipitable material was subjected to mild alkaline methanolysis for 50 min at 50°C. After mild alkaline methanolysis, the extracts were dried and samples were resuspended in water by sonication to measure total incorporated [3H]serine. The alkali-stable [3H]serine-labeled lipids were extracted with water-saturated butanol twice and dried, and samples were resuspended in chloroform/methanol/water (10:10:3) and normalized by total incorporated [3H]serine. Normalized samples were applied to Whatman Linear K6D silica gel thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates and resolved in CHCl3/methanol/4.2 N NH4OH (9:7:2) for 75 min. This condition could discriminate the band of ceramide from the band of unknown lipid “X” (top band observed on all TLC plates). For long pulse-labeling experiments, cells from early-log-phase cultures were labeled with 30 μCi of [3H]serine for 6 h. After labeling, sphingolipids were extracted as described above and separated by TLC. Radioactive bands were visualized by X-ray film after treatment with En3Hance (NEN Life Science Products). For quantitative analysis of sphingolipid synthesis, radioactive lipid bands were scraped with a razor blade from TLC plates and measured by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Identification of each sphingolipid was done using treatment with several known inhibitors of sphingolipid biosynthesis and by [3H]inositol labeling. We always detect the band labeled “X,” which appears at the top of each TLC plate, even under conditions where sphingolipid synthesis was completely blocked by treatment with myriocin, indicating that this lipid is likely not a sphingolipid.

Fluorescence microscopy.

All fluorescence images were observed using a Zeiss Axiovert S1002TV fluorescence microscope and subsequently processed using a DeltaVision deconvolution system. For actin localization, cells were grown to early log phase, shifted to 38°C for 90 min, fixed, and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin (Molecular Probes) as described previously (2).

Yeast two-hybrid analysis.

The sequences encoding SLM1, SLM2, CNA2, and CNB1 were PCR amplified from yeast genomic DNA with Pfu Ultra polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) or KOD polymerase (EMD Bioscience, San Diego, CA). The amplified fragments were cloned into two-hybrid vectors, pGADGH or pGBT9 (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.), via SmaI-SalI sites. All fusions constructs were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. Yeast strain HF7c (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.) was cotransformed with pGADGH expressing a Gal4 activation domain (ADGal4) fusion protein and pGBT9 expressing a Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBDGal4) fusion protein. The resultant transformants were spotted onto selective agar media and incubated at 30°C for 4 days. Interactions were scored by assessing growth on media lacking histidine.

GST affinity binding assays.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-SLM2436-656 and GST-SLM2436-640 constructs were made by cloning residues 436 to 656 and 436 to 640, respectively, of SLM2 into the SmaI-XhoI sites of the pGEX-6P-1 vector (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). GST or GST fusion constructs were transformed into JM101 Escherichia coli, and batch purification was performed using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham). Yeast cells expressing C-terminal myc13-tagged Cna2 were cultured in YNB media, converted to spheroplasts, and lysed in lysis buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors) for 30 min on ice. Unlysed cells were removed by centrifugation, and lysates were incubated with the appropriate GST fusion protein bound to glutathione beads for 2 h at 4°C. After 2 h, beads were washed with lysis buffer and bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer at 65°C for 5 min. The presence of Cna2 was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-myc monoclonal antibody (9E10).

RESULTS

SGA analysis uncovers a network of STT4 genetic interactions.

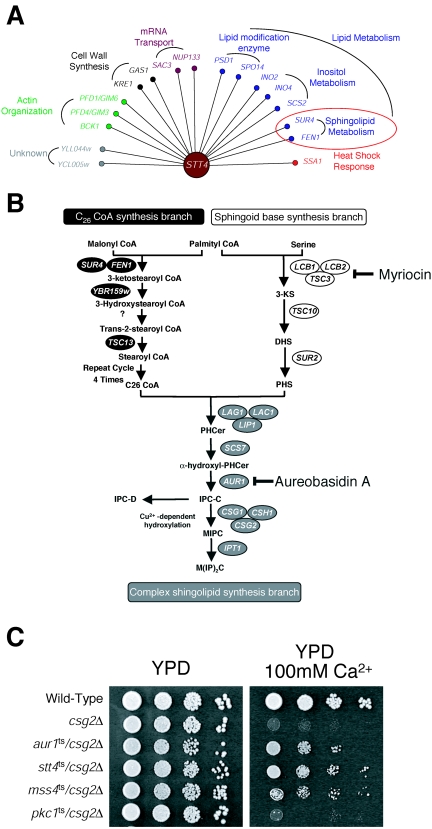

Genetic and biochemical evidence indicate the existence of two distinct yet essential pools of PI4P in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (2, 11, 41). The Stt4 PI 4-kinase generates PI4P at the plasma membrane, required for maintaining actin cytoskeleton organization (2), while Pik1 mediates the production of PI4P at the Golgi complex, necessary for normal protein secretion (2, 16, 38). A recent study using SGA analysis identified a set of genetic interactions specific to PIK1 (31). Here, we use a similar approach to identify potential regulators or effectors of Stt4-generated PI4P. Briefly, deletion mutations in the stt4ts background that resulted in synthetic growth defects or inviability at a temperature normally permissive to stt4ts single-mutant cells were systematically isolated. In total, 17 genes were identified, many of which are known to function in lipid biosynthetic pathways or regulate actin cytoskeleton organization (Fig. 1A). Importantly, the SGA analysis identified two genes, PSD1 and BCK1, previously shown to be required for the viability of stt4ts mutant cells (1, 36), validating the screen. In addition, several genes whose products function in phospholipid metabolism (SPO14, INO2, INO4, and SCS2) (23) and in sphingolipid biosynthesis (FEN1 and SUR4) (29) were found. Together, these data suggest alternative roles for Stt4-generated PI4P, independent of its previously characterized function in regulating actin organization.

FIG. 1.

SGA analysis using the stt4ts mutation identifies a genetic interaction between sphingolipid and phosphoinositide biosynthesis. (A) The genes required for normal growth of stt4ts cells are represented as nodes. Each node is color coded based on its functional classification as defined by published literature. All interactions were confirmed using direct tetrad analysis. (B) A diagram illustrating the sphingolipid biosynthetic pathway in yeast. (C) Wild-type, csg2Δ, aur1ts/csg2Δ, stt4ts/csg2Δ, mss4ts/csg2Δ, and pkc1ts/csg2Δ mutant cells were grown on YPD media with or without 100 mM CaCl2 at 26°C for 2 days.

Stt4 genetically interacts with multiple components of the sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway.

Identification of both FEN1 and SUR4, two genes encoding enzymes that function in a common fatty acid elongation pathway required for sphingolipid production (29) (Fig. 1B), in the stt4ts SGA analysis prompted us to further investigate a role for phosphoinositides in sphingolipid metabolism. It should be noted that essential genes required for sphingolipid synthesis could not be tested using SGA analysis, and FEN1 and SUR4 represent two of the very few nonessential genes that function in this pathway. Interestingly, previous studies implicated the PI4P 5-kinase Mss4, which functions downstream of Stt4, in the regulation of IPC (4), one of the three major sphingolipids in yeast (9). Specifically, a mutation in MSS4 suppressed the calcium sensitivity of csg2Δ mutant cells, which fail to efficiently mannosylate IPC and therefore accumulate high levels of this sphingolipid. The calcium sensitivity of csg2Δ mutant cells has been attributed to elevated levels of IPC, and mutations that decrease IPC levels restore growth in the presence of calcium (4). Consistent with this idea, deletion of either FEN1 or SUR4 rescued the growth of csg2Δ mutant cells on media containing calcium (20). To test whether mutation of Stt4 also restores normal calcium sensitivity to csg2Δ mutant cells, we generated stt4ts/csg2Δ double-mutant cells and scored their growth on calcium-containing media. Strikingly, stt4ts/csg2Δ double-mutant cells grew well in the presence of 100 mM calcium, similar to the growth of mss4ts/csg2Δ double-mutant cells (Fig. 1C). These data argue that Stt4-generated PI4P may be required for IPC synthesis. Furthermore, mutations in the Rho1/Pkc1 pathway, which functions downstream of Stt4, did not rescue the calcium sensitivity of csg2Δ mutant cells (Fig. 1C and data not shown), indicating that Stt4 functions in sphingolipid metabolism independently of its role in activating Rho1/Pkc1.

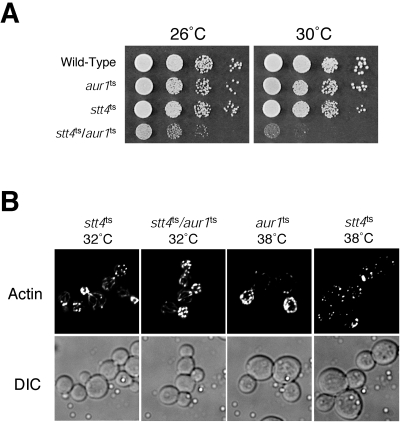

To further explore the role of Stt4 in IPC synthesis, we examined the growth of stt4ts cells in the presence of aureobasidin A, a compound which specifically inhibits Aur1, an essential enzyme required for the final step of IPC synthesis (27). Consistent with our data implicating Stt4 in IPC synthesis, stt4ts cells were hypersensitive to aureobasidin A (data not shown). Moreover, we found that the stt4ts mutation was synthetically lethal with an aur1ts mutation (Fig. 2A), isolated using error-prone PCR mutagenesis, at a temperature normally permissive to each single mutant. Importantly, stt4ts/aur1ts double-mutant cells did not show a synthetic defect in actin cytoskeleton organization at 32°C, exhibiting actin patches mostly restricted to the bud and actin cables extending through the mother cells, similar to wild-type cells (Fig. 2B). These data again argue for a direct role for Stt4 in IPC synthesis, independent of its previously characterized function in Rho1/Pkc1-mediated actin remodeling.

FIG. 2.

Both Aur1 and Stt4 function in sphingolipid metabolism. (A) Tenfold serial dilutions of the indicated cells were spotted on YPD at 26°C or 30°C for 2 days. (B) stt4ts, stt4ts/aur1ts, and aur1ts cells were incubated for 90 min at the indicated temperatures. Cells were fixed and stained with rhodamine-phalloidin and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. DIC, differential interference contrast.

Normal sphingolipid biosynthesis requires Stt4/Mss4-mediated phosphoinositide production.

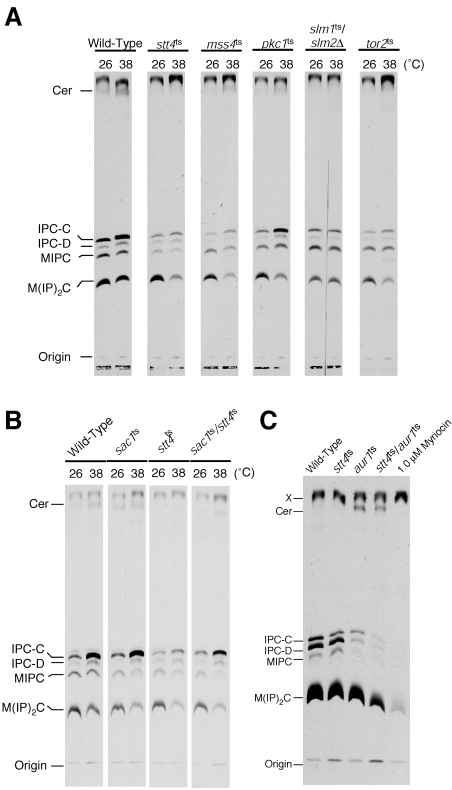

To examine directly whether sphingolipid (and/or sphingolipid precursor) levels are altered in cells impaired for Stt4 activity, sphingolipids were extracted from wild-type or stt4ts cells that had been labeled with [3H]serine at 26°C or 38°C and analyzed by TLC. Previous studies have shown that de novo sphingolipid synthesis is transiently elevated during heat shock (39). Consistent with this observation, wild-type cells showed a two- to threefold increase in ceramide and IPC levels at 38°C compared to levels observed at 26°C (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, the heat shock-induced elevation in sphingolipid and ceramide levels was significantly reduced in stt4ts cells (Fig. 3A). To determine whether this was due to a specific defect in PI4P synthesis, we also measured sphingolipid and ceramide levels in stt4ts cells harboring a temperature-sensitive form of Sac1, a phosphoinositide phosphatase that dephosphorylates Stt4-generated PI4P (12). Consistent with a direct role for PI4P in maintaining normal cellular IPC and ceramide levels, simultaneous inactivation of Stt4 and Sac1 partially rescued the defect in heat-induced elevation of ceramide and IPC observed in stt4ts cells (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

stt4ts and mss4ts cells exhibit a defect in heat shock-induced IPC-C synthesis. (A) Wild-type, stt4ts, mss4ts, slm1ts/slm2Δ, tor2ts, and pkc1ts cells were preincubated at the appropriate temperature for 10 min and labeled with [3H]serine for 80 min. Sphingolipids were extracted after mild alkaline methanolysis, normalized using total incorporated [3H]serine, and analyzed by TLC. Experiments were repeated at least 5 times, with each showing results similar to those presented. (B) Wild-type, stt4ts, sac1ts, and sac1ts/stt4ts cells were preincubated at the appropriate temperature for 10 min and labeled with [3H]serine for 80 min. Sphingolipids were then extracted and analyzed by TLC as described above. Experiments were repeated at least two times, yielding very similar results. (C) Wild-type, stt4ts, aur1ts, stt4ts/aur1ts, and 1.0 μM myriocin-treated wild-type cells were labeled with [3H]serine for 6 h at 30°C. Sphingolipids were then extracted and analyzed by TLC as described above.

To further understand the role for Stt4 in IPC and ceramide synthesis, we also examined sphingolipid levels in stt4ts/aur1ts cells, which show a potent growth defect compared to either single mutant alone. Cells were labeled with [3H]serine for 6 h at 30°C, and extracted sphingolipids were analyzed by TLC. While stt4ts and aur1ts single-mutant cells exhibited slightly decreased levels of IPC compared to wild-type cells, stt4ts/aur1ts double-mutant cells exhibited a severe reduction in cellular IPC (Fig. 3C). However, abnormal ceramide accumulation observed in aur1ts cells at 30°C was not significantly affected by the stt4ts mutation. These data suggest that the growth defect observed in stt4ts/aur1ts double-mutant cells results from reduced levels of IPC due to either insufficient IPC synthesis or increased IPC turnover.

To determine whether Mss4-mediated conversion of PI4P to PI4,5P2 was also important for heat-induced sphingolipid elevation, mss4ts cells were labeled at 26°C and 38°C with [3H]serine, and sphingolipids were extracted and resolved by TLC. Similar to results observed in stt4ts cells, mss4ts mutant cells also exhibited a significant reduction in IPC levels at the nonpermissive temperature (Fig. 3A). However, elevation of PI4,5P2 levels (either by overexpression of Mss4 or deletion of two synpatojanin-like PI 5-phosphatases, SJL1 and SJL2, failed to significantly alter sphingolipid levels (data not shown), suggesting that phosphoinositides do not likely act in a rate-limiting manner during sphingolipid synthesis. It should also be noted that pik1ts mutant cells did not exhibit a defect in heat shock-induced IPC elevation (data not shown). Importantly, mutations in components of the Rho1/Pkc1 pathway known to function downstream of Stt4 and Mss4 failed to affect heat-induced elevation of ceramide or IPC (Fig. 3A and data not shown). Together, these data confirm that Stt4 and Mss4 regulate IPC levels independently of their previously characterized roles in activation of Rho1/Pkc1.

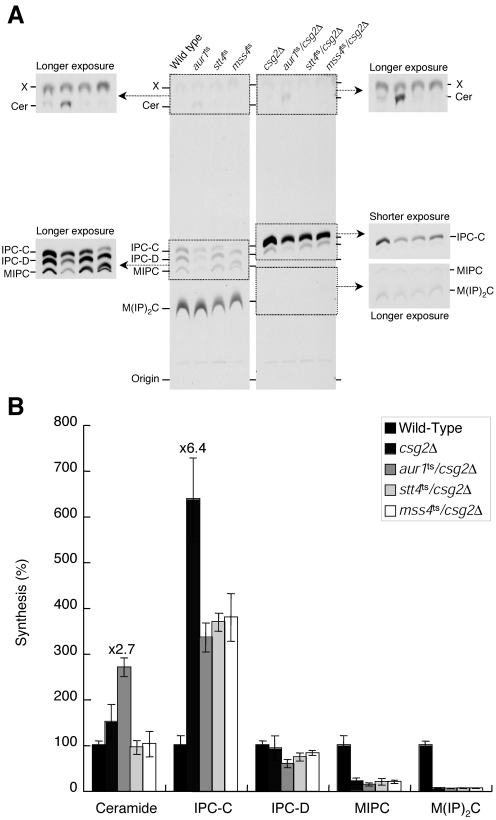

Since mutations in either STT4 or MSS4 were able to restore normal growth to csg2Δ mutant cells in the presence of calcium, we also wanted to directly examine whether partial defects in PI4P and PI4,5P2 production were sufficient to lower IPC levels in the absence of heat shock. Wild-type and mutant cells were labeled with [3H]serine for 6 h at 30°C, and sphingolipids were extracted for analysis by TLC. IPC levels (specifically IPC-C) in csg2Δ cells were approximately 6.4-fold higher than those observed in wild-type cells, while mannosylated sphingolipid levels were more than 10-fold reduced relative to wild-type cells (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, IPC-C levels in aur1ts/csg2Δ double-mutant cells were significantly reduced compared to csg2Δ single-mutant cells (Fig. 4A and B). Importantly, although IPC-C levels in aur1ts/csg2Δ cells were still approximately 3.4-fold higher than that in wild-type cells, this reduction appeared to be sufficient for restoring growth of csg2Δ mutant cells on calcium-containing media (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, IPC-C levels in stt4ts/csg2Δ and mss4ts/csg2Δ double-mutant cells were also decreased to levels similar to those found in aur1ts/csg2Δ cells. These results suggest that the increased calcium sensitivity exhibited by csg2Δ mutant cells is a consequence of elevated IPC-C levels, which depend at least in part on Stt4- and Mss4-mediated phosphoinositide production.

FIG. 4.

The Stt4-Mss4 phosphoinositide synthesis pathway is necessary for elevated IPC levels observed in csg2Δ cells. (A) Wild-type, aur1ts, stt4ts, mss4ts, csg2Δ, aur1ts/csg2Δ, stt4ts/csg2Δ, and mss4ts/csg2Δ cells were preincubated at 30°C for 10 min and labeled with [3H]serine for 6 h. Sphingolipids were extracted and analyzed by TLC as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (B) Quantification of sphingolipid levels in wild-type, csg2Δ, aur1ts/csg2Δ, stt4ts/csg2Δ, and mss4ts/csg2Δcells that were labeled in panel A. Lipids were recovered from TLC plates by scraping and measured using a scintillation counter. The relative amount of each species was determined as a percentage of that observed in wild-type cells. The data represent the means ± standard errors of the means of results from three independent experiments.

PI4,5P2 effectors Slm1 and Slm2 participate in sphingolipid metabolism and are required for viability of csg2Δ cells.

Recent studies have identified two new effectors of phosphoinositide signaling at the plasma membrane, Slm1 and Slm2 (3, 10). Interestingly, Slm1 and Slm2 have also been found to function downstream of TORC2, a protein kinase complex required for actin cytoskeleton organization. To determine whether these proteins may function in sphingolipid metabolism, slm1ts/slm2Δ and tor2ts cells were labeled at 26°C and 38°C with [3H]serine, and sphingolipids were extracted and resolved by TLC. Similar to stt4ts and mss4ts cells, slm1ts/slm2Δ and tor2ts cells also exhibited a defect in heat-induced IPC levels (Fig. 3A). Consistent with these data, two components of TORC2, Tor2 and Avo3, have previously been shown to rescue the calcium sensitivity of csg2Δ mutant cells (4).

To further explore the role of Slm1 and Slm2 in sphingolipid metabolism, we analyzed the effect of deleting CSG2 in the slm1ts/slm2Δ background. Surprisingly, deletion of CSG2 in slm1ts/slm2Δ mutant cells was lethal (Fig. 5A). Previous studies indicated that Slm1 is expressed at approximately 10-fold higher levels than Slm2 (3). Consistent with this observation, slm1Δ/csg2Δ double-mutant cells showed a temperature-sensitive growth defect, while slm2Δ/csg2Δ double-mutant cells grew similarly to csg2Δ single-mutant cells (Fig. 5B). Strikingly, deletion of SLM1 failed to rescue the growth defect exhibited by csg2Δ cells on calcium-containing media (data not shown). These data suggest that Slm1 and Csg2 may functionally interact.

FIG. 5.

Cells lacking both Slm1 and Csg2 exhibit synthetic defects in growth and actin cytoskeleton organization. (A) SLM1/slm2Δ/csg2Δ, slm1Δ/slm2Δ/csg2Δ, slm1ts/slm2Δ/csg2Δ, and slm1ts/slm2Δ/CSG2 cells carrying a URA3-marked SLM1 plasmid were incubated on media containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) at 26°C for 3 days. (B) Wild-type, csg2Δ, slm1Δ, slm2Δ, slm1Δ/csg2Δ, and slm2Δ/csg2Δ cells were grown at 26°C or 38°C for 2 days. (C) Wild-type, csg2Δ, slm1Δ, and slm1Δ/csg2Δ cells were shifted to 38°C for 90 min, fixed, stained with rhodamine-phalloidin, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. DIC, differential interference contrast.

Previous work has shown that slm1ts/slm2Δ cells exhibit a defect in actin organization (3, 10). However, the specific role for Slm1 and Slm2 in regulating actin has yet to be elucidated. To determine if deletion of CSG2 in slm1Δ mutant cells affected actin organization, we stained slm1Δ/csg2Δ cells with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin following a 90-min shift to the nonpermissive temperature. Unlike slm1Δ or csg2Δ single-mutant cells, slm1Δ/csg2Δ double-mutant cells exhibited a complete depolarization of the actin cytoskeleton at 38°C (Fig. 5C), suggesting that Csg2 functions with Slm1 to regulate actin organization.

Deletion of CSG2 perturbs Slm1 phosphorylation and elevates calcineurin activity.

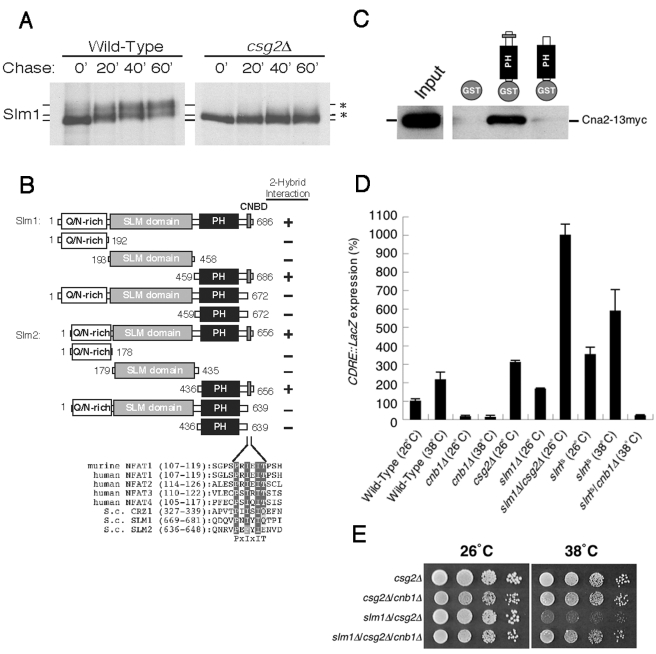

To gain further insight into the functional relationship between Slm1 and Csg2, we next examined the phosphorylation state of Slm1 in csg2Δ cells. We have previously shown that Slm1 is phosphorylated by TORC2, which can be observed as a gel mobility shift in Slm1 following SDS-PAGE analysis (3). Wild-type and csg2Δ cells expressing Slm1-GFP were pulse-labeled with [35S]cysteine and methionine for 10 min at 26°C and chased with unlabeled cysteine and methionine, followed by immunoprecipitation using GFP antibodies and analysis by SDS-PAGE. Strikingly, the shift in Slm1 gel mobility normally seen in wild-type cells was absent in csg2Δ mutant cells (Fig. 6A). This defect in Slm1 phosphorylation was not a result of mislocalization, as determined by fluorescence microscopy, and in contrast to previous work (19), Mss4 localization appeared unaffected by loss of Csg2 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Together, these data suggest that csg2Δ mutant cells exhibit decreased/mislocalized TORC2 kinase activity or hyperactivation of protein phosphatases. Interestingly, genome-wide two-hybrid analysis has shown that Slm2 interacts with both Cna1 and Cna2, α-subunits of calcineurin, and a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase (18, 37). Moreover, both Slm1 and Slm2 contain a putative calcineurin-binding motif in their C-terminal regions, P673NIYIQ678 and P640EFYIE646, respectively (Fig. 6B) (6). To test whether these putative calcineurin-binding domains in Slm1 and Slm2 are functional, we performed a directed yeast two-hybrid analysis. We found that both Slm1 and Slm2 could interact with Cna2, but deletion of the C-terminal putative calcineurin-binding domains from either protein eliminated binding (Fig. 6B). The specificity of this interaction was further confirmed using a GST pull-down assay in which a GST fusion to the C terminus of Slm2, but not GST alone, bound full-length myc-tagged Cna2 (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

Calcineurin directly binds to Slm1 and Slm2 through their C-terminal calcineurin binding motifs. (A) Wild-type or csg2Δ cells expressing SLM1-GFP were metabolically labeled for 10 min with [35S]cysteine and methionine and chased for the indicated time at 26°C. Extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibodies and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis followed by autoradiography. (B) Yeast two-hybrid analysis was used to assay the interaction of Slm1 and Slm2 with calcineurin, based on histidine-independent growth. (C) GST, GST-Slm2, and GST-Slm2 lacking its C-terminal calcineurin binding motif were bound to glutathione beads, which were incubated with yeast cell lysates containing myc-tagged Cna2. Bound Cna2 was detected by Western blot analysis using anti-myc antibodies. (D) Wild-type, cnb1Δ, csg2Δ, slm1Δ, slm1Δ/csg2Δ, slmts, and slmts/cnb1Δ cells carrying the 4× CDRE-lacZ reporter plasmid (AMS366) were grown to log phase at 26°C and shifted to the indicated temperatures for 2 h, and β-galactosidase activity was determined. The data represent the means ± standard errors of the means of results from three independent experiments. (E) csg2Δ, csg2Δ/cnb1Δ, slm1Δ/csg2Δ, and slm1Δ/csg2Δ/cnb1Δ cells were grown on YPD at 26 or 38°C for 2 days.

To determine whether elevated calcineurin activity may have been responsible for Slm1 dephosphorylation in csg2Δ mutant cells, csg2Δ mutant cells were treated with the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 and Slm1 phosphorylation was monitored. Consistent with a role for calcineurin in Slm1 dephosphorylation, FK506 partially restored Slm1 phosphorylation in csg2Δ mutant cells (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Moreover, we confirmed that calcineurin activity was elevated in csg2Δ mutant cells using the CDRE::lacZ reporter element, whose expression is dependent on both calcineurin and its substrate, the Crz1/Tcn1 transcription factor (26, 32). The expression of CDRE::lacZ in csg2Δ cells was increased 3.1-fold higher than that in wild-type cells (Fig. 6D). Surprisingly, the CDRE::lacZ expression was slightly increased in slm1Δ cells, and slm1Δ/csg2Δ double-mutant cells exhibited 10-fold higher CDRE::lacZ expression (Fig. 6D). We also found that CDRE::lacZ expression was increased in slm1ts/slm2Δ cells at both 26°C and 38°C (Fig. 6D) as well as in mss4ts and tor2ts cells (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that Slm1, Slm2, and Csg2 cooperate to negatively regulate cellular calcineurin activity. Consistent with these data, deletion of calcineurin rescued the temperature-sensitive growth defect of slm1Δ/csg2Δ double-mutant cells (Fig. 6E).

Calcineurin alters sphingolipid metabolism.

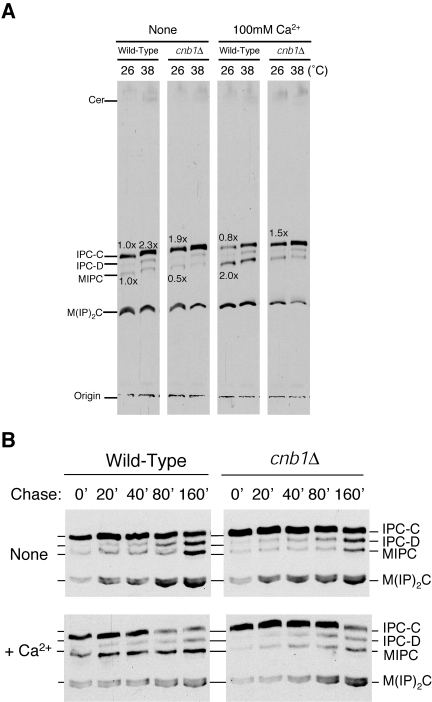

Loss of Slm1 and Slm2 function results in hyperactivation of calcineurin and defects in sphingolipid biosynthesis. To determine if activated calcineurin affects sphingolipid levels, we treated cells with 100 mM Ca2+ to activate calcineurin, labeled them with [3H]serine at 26 and 38°C, and analyzed extracted sphingolipids by TLC. As a control, we labeled cnb1Δ cells, which lack calcineurin activity (8, 21). Following a 20-min pretreatment with 100 mM Ca2+, we observed altered levels of both IPC and MIPC in wild-type cells but not in cnb1Δ cells (Fig. 7A). By extracting sphingolipids following different periods of chase, we found that elevated calcineurin activity altered sphingolipid metabolism, accelerating the conversion of IPC to MIPC and causing a net decrease in IPC levels within cells (Fig. 7B). These data suggest that elevated calcineurin activity may at least in part be responsible for the defects in sphingolipid metabolism observed in slm1ts/slm2Δ mutant cells. Consistent with this idea, deletion of calcineurin in slm1ts/slm2Δ cells partially suppressed its temperature sensitivity (Fig. 8A). Moreover, deletion of calcineurin restored levels of IPC in slm1ts/slm2Δ cells to those observed in wild-type cells (Fig. 8B). Together, these data suggest that misregulation/hyperactivation of calcineurin is likely one of the most significant defects directly associated with loss of Slm1 and Slm2 function. Interestingly, deletion of calcineurin in csg2Δ mutant cells failed to suppress their calcium sensitivity. In fact, calcium sensitivity was heightened in csg2Δ/cnb1Δ double-mutant cells compared to either single mutant, suggesting additional, yet to be determined roles for calcineurin under conditions where IPC is elevated (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

FIG. 7.

Calcineurin activity is required for the Ca2+-induced acceleration conversion of IPC to MIPC. (A) Cells were preincubated at 26°C for 10 min with or without 100 mM Ca2+, shifted to the appropriate temperature for 10 min, labeled with [3H]serine for 20 min, and chased for 60 min. Sphingolipids were extracted after mild alkaline methanolysis and analyzed by TLC as described in the legend to Fig. 3A. (B) Cells were metabolically labeled with [3H]serine for 20 min and chased for the indicated time. Sphingolipids were extracted and analyzed by TLC as described in the legend to Fig. 3A.

FIG. 8.

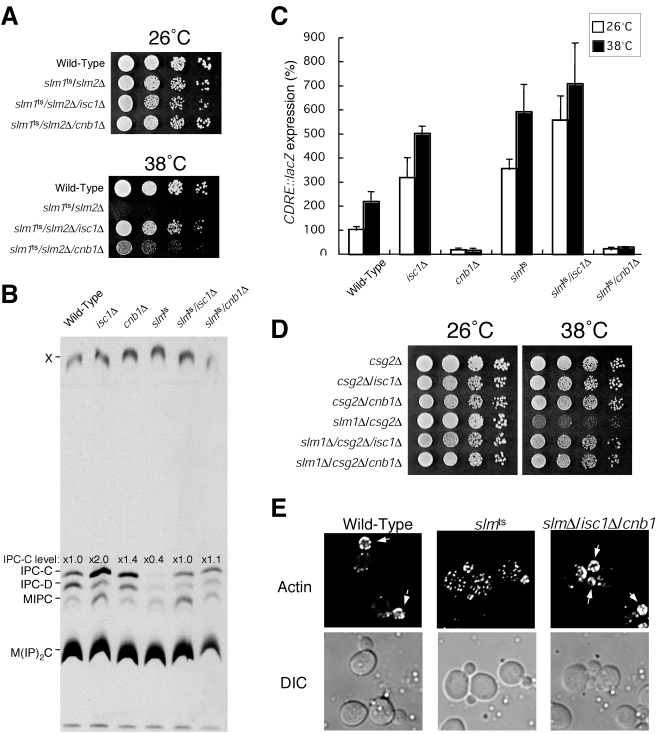

Deletion of ISC1 or CNB1 suppresses the phenotypes associated with loss of Slm1 and Slm2 function. (A) Wild-type and slm1ts/slm2Δ, slm1ts/slm2Δ/isc1Δ, and slm1ts/slm2Δ/cnb1Δ mutant cells were grown on YPD at 26°C or 38°C for 2 days. (B) Wild-type, isc1Δ, cnb1Δ, and slm1ts/slm2Δ, slm1ts/slm2Δ/isc1Δ and slm1ts/slm2Δ/cnb1Δ′ cells were metabolically labeled with [3H]serine for 6 h. Sphingolipids were analyzed by TLC. (C) Wild-type, isc1Δ, cnb1Δ, slm1ts/slm2Δ, slm1ts/slm2Δ/isc1Δ and slm1ts/slm2Δ/cnb1Δ cells carrying the 4× CDRE-lacZ reporter plasmid (AMS366) were grown to log phase at 26°C and shifted to 38°C for 2 h, and β-galactosidase activity was determined. The data shown represent the means ± standard errors of the means of results from three independent experiments. (D) csg2Δ, csg2Δ/isc1Δ, csg2Δ/cnb1Δ, slm1Δ/csg2Δ, slm1Δ/csg2Δ/isc1Δ, and slm1Δ/csg2Δ/cnb1Δ cells were grown on YPD at 26 or 38°C for 2 days. (E) Wild-type, slm1ts/slm2Δ and slm1Δ/slm2Δ/isc1Δ/cnb1Δ cells were shifted to 38°C for 2 h, fixed, stained with rhodamine-phalloidin, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. DIC, differential interference contrast.

Decreased IPC levels in slm1ts/slm2Δ cells is in part due to elevated Isc1 activity.

Although calcineurin activity was elevated in slm1ts/slm2Δ, mss4ts, and tor2ts mutant cells, mannosylated IPC levels were not significantly altered compared to control cells (Fig. 3C). Therefore, another factor(s) likely contributes to the decreased levels of IPC observed in these mutant cells. Isc1, an inositol phosphosphingolipid phospholipase C homologous to mammalian sphingomyelinase (30), was an attractive candidate, since enhanced degradation of IPC may be a direct cause of changes in sphingolipid metabolism. Consistent with a role for Isc1 in sphingolipid degradation, cells lacking Isc1 showed a twofold increase in IPC levels (Fig. 8B). Interestingly, deletion of ISC1, like deletion of calcineurin, restored IPC levels observed in slm1ts/slm2Δ mutant cells to those seen in wild-type cells (Fig. 8B), and unlike slm1ts/slm2Δ cells, slm1ts/slm2Δ/isc1Δ triple-mutant cells were not temperature sensitive for growth, even though calcineurin activity in these cells was significantly elevated (Fig. 8A and C). Additionally, deletion of ISC1 was sufficient to rescue the synthetic growth defect exhibited by slm1Δ/csg2Δ double-mutant cells, similar to that observed following loss of calcineurin (Fig. 8D).

Together, these data suggest that misregulation/hyperactivation of Isc1 and calcineurin are likely the major defects directly associated with loss of Slm1 and Slm2 function. Consistent with this idea, deletion of both ISC1 and calcineurin in slm1Δ/slm2Δ cells completely rescued the actin organization and cell viability defects associated with complete loss of Slm1 and Slm2 function (Fig. 8E), while deletion of either ISC1 or calcineurin alone could only partially rescue these phenotypes (data not shown). In contrast, deletion of ISC1 or calcineurin failed to have a significant impact on the growth of stt4ts cells, indicating roles for PI4P beyond that of Slm1 and Slm2 regulation (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

SGA analysis implicates Stt4-dependent PI4P in sphingolipid homeostasis.

We have previously performed SGA analysis to identify components of phosphoinositide signaling at both the Golgi, using an allele of the PI 4-kinase Pik1 (31), and the plasma membrane, using an allele of the PI4P 5-kinase Mss4 (3). In this study, we identify a unique set of genes that are essential under conditions where Stt4-generated PI4P is modestly reduced, likely corresponding to regulators or effectors of PI4P. Consistent with previous work indicating independent roles for the Stt4 and Pik1 PI 4-kinases (2), we found no overlap between genes identified here and those identified in the Pik1 SGA analysis. However, we were surprised to find only a few genes in common between the Stt4 and Mss4 SGA screens, since Stt4 and Mss4 have been previously shown to function in a common pathway to control actin organization (1). Instead, SGA analysis of Stt4 uncovered several genes whose products have been implicated in lipid metabolism. In particular, we found that deletion of either FEN1 or SUR4, whose gene products are required for long chain fatty acid synthesis (29), in the stt4ts background resulted in lethality. Since long chain fatty acids are required for sphingolipid biosynthesis, these data suggested that, in addition to its role in actin organization and cell wall integrity, Stt4 may also function upstream of sphingolipid production. Consistent with this idea, we showed that stt4ts cells exhibit a defect in heat shock-induced production of IPC. Furthermore, we found that two downstream effectors of phosphoinositide signaling, Slm1 and Slm2, are also required to maintain normal cellular IPC levels, at least in part through their role in regulating calcineurin. Together, these data argue that phosphoinositides interface with other lipid synthesis pathways to direct changes in membrane composition and/or architecture.

Role of phosphoinositides in the regulation of sphingolipid metabolism and actin organization.

Previous work has suggested a link between phosphoinositides and sphingolipid synthesis (4). In particular, a temperature-sensitive allele of MSS4 was isolated in a genetic screen for mutants that could restore normal calcium sensitivity to cells lacking Csg2, an enzyme that normally converts IPC to MIPC. csg2Δ cells accumulate elevated levels of IPC-C, which is thought to underlie their sensitivity to calcium, and mutations that perturb IPC-C synthesis suppress this phenotype (4). These data implicated Mss4 in sphingolipid metabolism. Similarly, we found that mutations in STT4 could also suppress the calcium sensitivity of csg2Δ cells, supporting a role for phosphoinositides in regulating sphingolipid production, and both stt4ts and mss4ts cells exhibited a defect in heat shock-induced IPC-C levels. Surprisingly, SGA analysis of Mss4 failed to identify components of the sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway (3). One potential explanation is that the allele of STT4 used here perturbs phosphoinositide levels at permissive temperature more severely than the allele of MSS4 examined previously. Alternatively, Stt4 and PI4P may play additional and more direct roles in sphingolipid metabolism, independent of their function upstream of Mss4, Slm1, Slm2, and calcineurin. Consistent with this idea, unlike slm1ts/slm2Δ and mss4ts cells, calcineurin was not hyperactivated in stt4ts cells compared to wild-type cells (data not shown). Further study will be necessary to determine the relative contributions of Stt4 and Mss4 activities to sphingolipid metabolism.

Through the regulation of several effector molecules, phosphoinositides dependent on Stt4 and Mss4 have been shown to function upstream of the Rho1/Pkc1 pathway, which regulates actin organization and cell wall integrity (1). Importantly, the role(s) for phosphoinositides in sphingolipid metabolism are independent of this cell integrity signaling cascade, since mutations in both RHO1 and PKC1 fail to perturb sphingolipid levels. In contrast, the essential PI4,5P2 binding proteins, Slm1 and Slm2, which have been suggested to function upstream of Rho1/Pkc1, also appear to function in sphingolipid metabolism. Both Slm1 and Slm2 are also regulated by phosphorylation, which is dependent on the TORC2 protein kinase complex (3). Like PI4,5P2, TORC2 has been shown to function upstream of Rho1, and loss of TORC2 function causes a disruption of actin organization. Interestingly, mutations in two components of TORC2, TOR2 and AVO3, were identified as suppressors of calcium sensitivity following deletion of CSG2 (4), suggesting that TORC2 also functions to regulate sphingolipid metabolism. Consistent with this idea, tor2ts cells exhibited a defect in heat shock-induced IPC-C levels. Together, these data suggest that both phosphoinositide levels and TORC2 protein kinase activity coordinately modulate Slm1 and Slm2 function to alter both sphingolipid synthesis and Rho1/Pkc1-mediated actin organization. Such a relationship between sphingolipid synthesis and actin organization would not be unprecedented. In addition to abrogating sphingolipid production, mutations in the serine palmitoyltransferase Lcb1 also result in a defect in actin organization (43) that can be suppressed by overexpression of Pkc1 (14).

Phosphoinositide effectors, Slm1 and Slm2, negatively regulate calcineurin to maintain sphingolipid levels.

Tandem affinity purification of Slm1 previously identified Slm2 as its only interacting partner (3). However, the stringent conditions used during purification resulted in the loss of other lower affinity Slm1/2-binding proteins (3). Interestingly, genome-wide two-hybrid screening identified calcineurin as a potential Slm2-interacting protein (18, 37). Calcineurin is a calcium/calmodulin-activated protein phosphatase that couples calcium signals to cellular responses (7). We confirmed the interaction between calcineurin and Slm2 and also identified a calcineurin-binding motif within Slm2 (and Slm1). Surprisingly, deletion of the calcineurin binding domains found in Slm1 and Slm2 failed to have any effect on cell viability or calcineurin activity (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). However, deletion of calcineurin partially rescued the temperature-sensitive growth defect of slm1ts/slm2Δ cells, suggesting that Slm1 and Slm2 negatively regulate calcineurin, likely in an indirect manner. Additionally, calcineurin appears to negatively regulate Slm1 and Slm2 through dephosphorylation, suggesting the existence of a negative feedback loop (Fig. 9).

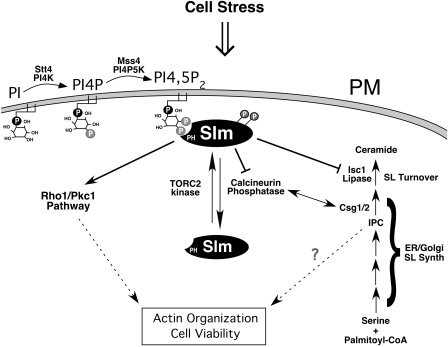

FIG. 9.

The phosphoinositide effectors Slm1 and Slm2 function in the regulation of sphingolipid metabolism and actin cytoskeleton organization. We speculate that Slm1 and Slm2 play multiple roles downstream of Stt4, Mss4, and the TORC2 protein kinase complex to regulate actin cytoskeleton organization, including the negative regulation of calcineurin and Isc1. Abbreviations: SL, sphingolipid; PM, plasma membrane; IPC, inositolphosphoceramide.

Previous work has also suggested a role for calcineurin in lipid and sterol metabolism (42). In particular, calcineurin has been shown to regulate the expression of CSG1, which functions together with Csg2 in the production of MIPC. Conversely, deletion of CSG2 has been shown to elevate intracellular levels of calcium, presumably leading to the activation of calcineurin (34). Interestingly, we found that elevated calcium altered sphingolipid metabolism, resulting in lower levels of cellular IPC. Therefore, we speculate that increased calcineurin activity in the absence of Slm1 and Slm2 contributes to the altered levels of sphingolipids observed. Consistent with this idea, deletion of calcineurin rescued the defect in sphingolipid levels observed in slm1ts/slm2Δ mutant cells.

In a similar fashion, the yeast inositol phosphosphingolipid phospholipase C Isc1 mediates conversion of IPC to ceramide (30). Dramatically, loss of this pathway strongly rescued phenotypes exhibited by slm1ts/slm2Δ double-mutant cells, suggesting the Slm1 and Slm2 also negatively regulate Isc1 activity. Together, these data argue that the major role of Slm1 and Slm2 is to preserve IPC levels through the inhibition of pathways that metabolize this sphingolipid. However, elevation of cellular IPC levels through the deletion of CSG2 is insufficient to rescue slm1ts/slm2Δ cells. One potential explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that Slm1 and Slm2 modulate a specific pool of IPC, which fails to be preserved in csg2Δ cells. Further studies will be necessary to determine the site of action of IPC that functions downstream of Slm1, Slm2, calcineurin, and Isc1 and to identify the set of IPC effectors that may function in this pathway to regulate actin cytoskeleton organization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Howard Riezman, Martha Cyert, and Kyle Cunningham for providing strains and plasmids and for useful discussions. We are grateful to Perla Arcaira, Joshua Kaufman, and Ngon Kim Vu for their helpful technical assistance. We thank members of the Emr lab, especially Chris Stefan, Simon Rudge, William Parrish, Joerg Urban, and Ji Sun, for their useful discussions.

M.T. was supported as an associate of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. A.A. is currently supported by a Helen Hay Whitney postdoctoral fellowship. S.D.E. is an established investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Audhya, A., and S. D. Emr. 2002. Stt4 PI 4-kinase localizes to the plasma membrane and functions in the Pkc1-mediated MAP kinase cascade. Dev. Cell 2:593-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audhya, A., M. Foti, and S. D. Emr. 2000. Distinct roles for the yeast phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases, Stt4p and Pik1p, in secretion, cell growth, and organelle membrane dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:2673-2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audhya, A., R. Loewith, A. B. Parsons, L. Gao, M. Tabuchi, H. Zhou, C. Boone, M. N. Hall, and S. D. Emr. 2004. Genome-wide lethality screen identifies new PI4,5P(2) effectors that regulate the actin cytoskeleton. EMBO J. 23:3747-3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beeler, T., D. Bacikova, K. Gable, L. Hopkins, C. Johnson, H. Slife, and T. Dunn. 1998. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae TSC10/YBR265w gene encoding 3-ketosphinganine reductase is identified in a screen for temperature-sensitive suppressors of the Ca2+-sensitive csg2Delta mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30688-30694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeler, T., K. Gable, C. Zhao, and T. Dunn. 1994. A novel protein, CSG2p, is required for Ca2+ regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 269:7279-7284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boustany, L. M., and M. S. Cyert. 2002. Calcineurin-dependent regulation of Crz1p nuclear export requires Msn5p and a conserved calcineurin docking site. Genes Dev. 16:608-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cyert, M. S. 2003. Calcineurin signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: how yeast go crazy in response to stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311:1143-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cyert, M. S., and J. Thorner. 1992. Regulatory subunit (CNB1 gene product) of yeast Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphoprotein phosphatases is required for adaptation to pheromone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3460-3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickson, R. C., and R. L. Lester. 2002. Sphingolipid functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1583:13-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fadri, M., A. Daquinag, S. Wang, T. Xue, and J. Kunz. 2005. The pleckstrin homology domain proteins Slm1 and Slm2 are required for actin cytoskeleton organization in yeast and bind phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate and TORC2. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:1883-1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flanagan, C. A., E. A. Schnieders, A. W. Emerick, R. Kunisawa, A. Admon, and J. Thorner. 1993. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase: gene structure and requirement for yeast cell viability. Science 262:1444-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foti, M., A. Audhya, and S. D. Emr. 2001. Sac1 lipid phosphatase and Stt4 phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase regulate a pool of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate that functions in the control of the actin cytoskeleton and vacuole morphology. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2396-2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friant, S., R. Lombardi, T. Schmelzle, M. N. Hall, and H. Riezman. 2001. Sphingoid base signaling via Pkh kinases is required for endocytosis in yeast. EMBO J. 20:6783-6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friant, S., B. Zanolari, and H. Riezman. 2000. Increased protein kinase or decreased PP2A activity bypasses sphingoid base requirement in endocytosis. EMBO J. 19:2834-2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaynor, E. C., S. te Heesen, T. R. Graham, M. Aebi, and S. D. Emr. 1994. Signal-mediated retrieval of a membrane protein from the Golgi to the ER in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 127:653-665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hama, H., E. A. Schnieders, J. Thorner, J. Y. Takemoto, and D. B. DeWald. 1999. Direct involvement of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate in secretion in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 274:34294-34300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito, H., Y. Fukuda, K. Murata, and A. Kimura. 1983. Transformation of intact yeast cells treated with alkali cations. J. Bacteriol. 153:163-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito, T., T. Chiba, R. Ozawa, M. Yoshida, M. Hattori, and Y. Sakaki. 2001. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4569-4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi, T., H. Takematsu, T. Yamaji, S. Hiramoto, and Y. Kozutsumi. 2005. Disturbance of sphingolipid biosynthesis abrogates the signaling of Mss4, phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 280:18087-18094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohlwein, S. D., S. Eder, C. S. Oh, C. E. Martin, K. Gable, D. Bacikova, and T. Dunn. 2001. Tsc13p is required for fatty acid elongation and localizes to a novel structure at the nuclear-vacuolar interface in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:109-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuno, T., H. Tanaka, H. Mukai, C. D. Chang, K. Hiraga, T. Miyakawa, and C. Tanaka. 1991. cDNA cloning of a calcineurin B homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 180:1159-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemmon, M. A. 2003. Phosphoinositide recognition domains. Traffic 4:201-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loewen, C. J., M. L. Gaspar, S. A. Jesch, C. Delon, N. T. Ktistakis, S. A. Henry, and T. P. Levine. 2004. Phospholipid metabolism regulated by a transcription factor sensing phosphatidic acid. Science 304:1644-1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Matheos, D. P., T. J. Kingsbury, U. S. Ahsan, and K. W. Cunningham. 1997. Tcn1p/Crz1p, a calcineurin-dependent transcription factor that differentially regulates gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 11:3445-3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagiec, M. M., E. E. Nagiec, J. A. Baltisberger, G. B. Wells, R. L. Lester, and R. C. Dickson. 1997. Sphingolipid synthesis as a target for antifungal drugs. Complementation of the inositol phosphorylceramide synthase defect in a mutant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the AUR1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 272:9809-9817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Odorizzi, G., M. Babst, and S. D. Emr. 2000. Phosphoinositide signaling and the regulation of membrane trafficking in yeast. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:229-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh, C. S., D. A. Toke, S. Mandala, and C. E. Martin. 1997. ELO2 and ELO3, homologues of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ELO1 gene, function in fatty acid elongation and are required for sphingolipid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17376-17384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Robinson, J. S., D. J. Klionsky, L. M. Banta, and S. D. Emr. 1988. Protein sorting in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: isolation of mutants defective in the delivery and processing of multiple vacuolar hydrolases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:4936-4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawai, H., Y. Okamoto, C. Luberto, C. Mao, A. Bielawska, N. Domae, and Y. A. Hannun. 2000. Identification of ISC1 (YER019w) as inositol phosphosphingolipid phospholipase C in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275:39793-39798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sciorra, V. A., A. Audhya, A. B. Parsons, N. Segev, C. Boone, and S. D. Emr. 2005. Synthetic genetic array analysis of the PtdIns 4-kinase Pik1p identifies components in a Golgi-specific Ypt31/rab-GTPase signaling pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:776-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stathopoulos, A. M., and M. S. Cyert. 1997. Calcineurin acts through the CRZ1/TCN1-encoded transcription factor to regulate gene expression in yeast. Genes Dev. 11:3432-3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Stefan C. J., A. Audhya, and S. D. Emr. 2002. The yeast synaptojanin-like proteins control the cellular distribution of phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:542-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takenawa, T., and T. Itoh. 2001. Phosphoinositides, key molecules for regulation of actin cytoskeletal organization and membrane traffic from the plasma membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1533:190-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanida, I., Y. Takita, A. Hasegawa, Y. Ohya, and Y. Anraku. 1996. Yeast Cls2p/Csg2p localized on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane regulates a non-exchangeable intracellular Ca2+ pool cooperatively with calcineurin. FEBS Lett. 379:38-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong, A. H., M. Evangelista, A. B. Parsons, H. Xu, G. D. Bader, N. Page, M. Robinson, S. Raghibizadeh, C. W. Hogue, H. Bussey, B. Andrews, M. Tyers, and C. Boone. 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294:2364-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trotter, P. J., W. I. Wu, J. Pedretti, R. Yates, and D. R. Voelker. 1998. A genetic screen for aminophospholipid transport mutants identifies the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, STT4p, as an essential component in phosphatidylserine metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13189-13196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uetz, P., L. Giot, G. Cagney, T. A. Mansfield, R. S. Judson, J. R. Knight, D. Lockshon, V. Narayan, M. Srinivasan, P. Pochart, A. Qureshi-Emili, Y. Li, B. Godwin, D. Conover, T. Kalbfleisch, G. Vijayadamodar, M. Yang, M. Johnston, S. Fields, and J. M. Rothberg. 2000. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403:623-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walch-Solimena, C., and P. Novick. 1999. The yeast phosphatidylinositol-4-OH kinase pik1 regulates secretion at the Golgi. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:523-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells, G. B., R. C. Dickson, and R. L. Lester. 1998. Heat-induced elevation of ceramide in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via de novo synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7235-7243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wild, A. C., J. W. Yu, M. A. Lemmon, and K. J. Blumer. 2004. The p21-activated protein kinase-related kinase Cla4 is a coincidence detector of signaling by Cdc42 and phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 279:17101-17110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida, S., Y. Ohya, M. Goebl, A. Nakano, and Y. Anraku. 1994. A novel gene, STT4, encodes a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase in the PKC1 protein kinase pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 269:1166-1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshimoto, H., K. Saltsman, A. P. Gasch, H. X. Li, N. Ogawa, D. Botstein, P. O. Brown, and M. S. Cyert. 2002. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression regulated by the calcineurin/Crz1p signaling pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 277:31079-31088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zanolari, B., S. Friant, K. Funato, C. Sutterlin, B. J. Stevenson, and H. Riezman. 2000. Sphingoid base synthesis requirement for endocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 19:2824-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.