Abstract

Human 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole sensitivity-inducing factor (DSIF) and negative elongation factor (NELF) negatively regulate transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) in vitro. However, the physiological roles of this negative regulation are not well understood. Here, by using a number of approaches to identify protein-DNA interactions in vivo, we show that DSIF- and NELF-mediated transcriptional pausing has a dual function in regulating immediate-early expression of the human junB gene. Before induction by interleukin-6, RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF accumulate in the promoter-proximal region of junB, mainly at around position +50 from the transcription initiation site. After induction, the association of these proteins with the promoter-proximal region continues whereas RNAPII and DSIF are also found in the downstream regions. Depletion of a subunit of NELF by RNA interference enhances the junB mRNA level both before and after induction, indicating that DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing contributes to the negative regulation of junB expression, not only by inducing RNAPII pausing before induction but also by attenuating transcription after induction. These regulatory mechanisms appear to be conserved in other immediate-early genes as well.

In eukaryotic cells, the regulation of preinitiation complex (PIC) assembly is essential to control gene expression (26), yet recent studies indicate that post-PIC assembly processes are also critical (27). At the human α1-AT locus, transcription initiation is inhibited before induction, although RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) associates with the promoter (29). In contrast, at the human c-fos and c-myc loci and some Drosophila heat shock loci, elongating RNAPII pauses in the promoter-proximal region before induction (12, 23, 24). The latter example is referred to as “promoter-proximal pausing,” although the mechanism and function of this regulatory mode are not well understood (13). At the Drosophila hsp70 locus, promoter-proximal pausing is thought to be mediated by two transcription elongation factors, 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole sensitivity-inducing factor (DSIF) and negative elongation factor (NELF) (34).

DSIF is a heterodimeric protein complex consisting of the Spt4 and Spt5 subunits (31). Human Spt5 (hSpt5) has a repeat region called the CTR and multiple copies of the KOW motif, which is also found in bacterial elongation factor NusG (39). NELF is a DSIF cofactor that consists of four subunits (38). NELF-A, encoded by Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome candidate gene 2, has an N-terminal homology to hepatitis delta antigen, which binds to RNAPII and activates elongation (36). NELF-B, encoded by the COBRA1 gene, is known to interact with the BRCA1 protein (41). NELF-C and -D are translational variants of the TH1 gene products (17). NELF-E, also known as RD, has Arg-Asp dipeptide repeats and an RNA recognition motif (38). Biochemical analysis has revealed that DSIF and NELF cooperatively bind to elongating RNAPII and induce transcriptional pausing, possibly through an interaction between NELF-E and nascent RNA (37). Transcriptional pausing is alleviated when positive elongation factor b (P-TEFb) phosphorylates the heptapeptide repeats of the C-terminal domain of RNAPII, as well as the CTR in the hSpt5 subunit of DSIF (32, 35). After pausing is reversed, DSIF instead stimulates elongation by an as-yet-unknown mechanism. Interestingly, DSIF and NELF are not evolutionarily conserved to the same extent (17). Although DSIF is highly conserved among eukaryotes and is essential for viability in yeast, some species, including yeast, lack all of the NELF subunits (10, 17). Indeed, promoter-proximal pausing has not been observed in yeast (13). Thus, promoter-proximal pausing may be involved in transcriptional regulation only in some species.

Only a limited number of studies have been reported on DSIF- and NELF-mediated transcriptional pausing. At the Drosophila hsp70 locus, both DSIF and NELF associate with RNAPII paused at positions +20 to +40 before induction (34). After heat shock, NELF dissociates from RNAPII but DSIF translocates downstream with the polymerase. Another study showed that human estrogen receptor α recruits the NELF complex to target gene promoters by physically interacting with NELF-B (3). It is suggested that NELF acts as a transcriptional attenuator at these loci and is important for controlling the duration and magnitude of hormonal responses. In zebra fish, the mutant called foggy, which carries a point mutation in the Spt5 gene and lacks the repression activity of DSIF, shows specific defects in neuronal differentiation during development, suggesting that DSIF- and NELF-mediated transcriptional pausing may be involved in the expression of only a limited number of genes (9). However, its precise role in gene expression on a genome-wide basis remains unclear.

The goal of this study was to understand the physiological role of DSIF- and NELF-mediated transcriptional pausing. As a model, we used junB, an immediate-early gene (IEG) that is activated transiently and rapidly in response to a wide variety of extracellular stimuli, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6). junB encodes a basic leucine zipper protein, which functions as a component of the AP-1 transcriptional activator. Several studies indicate that the regulation of junB gene expression is important for cell growth and differentiation (11, 15, 20). Here we report that DSIF- and NELF-mediated transcriptional pausing has a dual role in the regulation of junB expression in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Our data indicate that pausing contributes to the negative regulation of junB expression not only by inducing transcriptional pausing before induction but also by attenuating the mRNA expression level after induction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Recombinant human IL-6 was from Peprotech, and restriction enzymes HaeIII and PvuII were from Toyobo. Antibodies against STAT3 (sc-7179), JunB (sc-805), TopoI (sc-10783), and normal-mouse immunoglobulin G (sc-2025) were from Santa Cruz. Anti-RNAPII (8WG16), anti-acetyl histone H4 (chromatin immunoprecipitation [ChIP] grade), and anti-histone H3 (ab1791) antibodies were from BABCO, Upstate, and Abcam, respectively. Antibodies against phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705 and Ser727) were from Cell Signaling. Anti-hSpt5 and anti-NELF-E antibodies have been described previously (31, 38).

Cell culture and IL-6 stimulation.

HepG2 cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The medium was replaced with 0.1% FBS-DMEM 24 h prior to IL-6 stimulation. IL-6 (0.5-mg/ml stock in 10 mM acetic acid) was added to the culture medium to a final concentration of 100 ng/ml.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was prepared by a guanidine thiocyanate extraction method using Sepasol I Super (Nacalai Tesque), followed by treatment with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega). The following primers were used: junB, 5′-CACCAAGTGCCGGAAGCGGA-3′ and 5′-AGGGGCAGGGGACGTTCAGA-3′; GAPDH, 5′-ATCCTGGGCTACACTGAGCA-3′ and 5′-GGTGGTCCAGGGGTCTTACT-3′; c-fos, 5′-CACTCCAAGCGGAGACAGAC-3′ and 5′-GAGCTGCCAGGATGAACTCT-3′; tis-11, 5′-GGGACTTGGGGGACAGTAAT-3′ and 5′-GAACCTCGGAAGACACTCCA-3′; 18S rRNA, 5′-TAGAGGGACAAGTGGCGTTC-3′ and 5′-TCCTCGTTCATGGGGAATAA-3′. RT-PCR was performed with the Titan One Tube RT-PCR system (Roche) as follows: 50°C for 30 min; 95°C for 15 min; and 20 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Real-time RT-PCR was performed with the iCycler iQ Detection System (Bio-Rad) and the QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (QIAGEN) as follows: 50°C for 30 min; 95°C 15 min; and 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The mRNA levels of junB shown in Fig. 5, as well as those of c-fos and tis-11 in Fig. 6, were normalized to the mRNA levels of GAPDH to allow comparisons among different experimental groups. The GAPDH expression level was measured and normalized to the level of 18S rRNA.

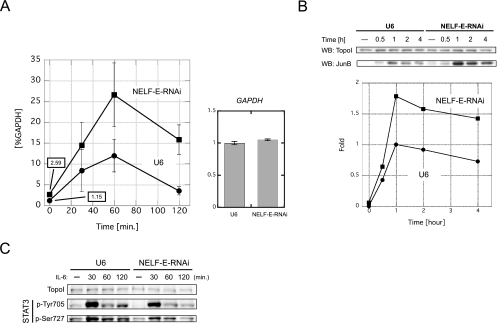

FIG. 5.

NELF-E knockdown upregulates junB gene expression at the mRNA level. (A, left) junB mRNA levels in NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells at various times after addition of IL-6. Total RNA was prepared and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. The mRNA level of each gene was normalized against the mRNA level of GAPDH. Numerical values of uninduced states are also presented on the graph. (A, right) GAPDH mRNA levels in NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells. Total RNA from unstimulated cells was subjected to real-time RT-PCR. The expression levels were normalized against the levels of 18S rRNA and are expressed in arbitrary units. Data obtained from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation. (B) JunB protein levels in NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells at various times after addition of IL-6. Whole-cell extracts were prepared and subjected to Western blot (WB) analysis with the indicated antibodies. The signal intensity of the blot was quantified with ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/) and is expressed as n-fold change. The intensity obtained from extracts of U6 cells stimulated for 1 h was set to 1. The result was confirmed to be reproducible (data not shown). (C) Phosphorylation status of STAT3 before and after induction. Western blot analysis was performed with the indicated antibodies.

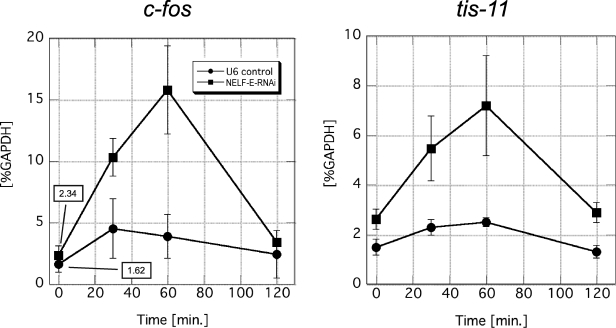

FIG. 6.

NELF-E knockdown upregulates the expression of other IEGs. The mRNA levels of c-fos and tis-11 in NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells at various times after addition of IL-6 are shown. Total RNA was prepared and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 5. The mRNA level of each gene was normalized against the mRNA level of GAPDH. Data obtained from three independent experiments, in which quantifications were done in triplicate, are shown as the mean ± the standard deviation. Numerical values of uninduced states are also presented in the graph on the left.

ChIP.

ChIP assays were performed essentially as previously described (18). About 600 μl of cross-linked lysate was prepared from a 15-cm dish, and a 50-μl aliquot was used per immunoprecipitation. Coprecipitated DNA was suspended in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA (TE), and 2-μl aliquots of each sample were used for real-time PCR with the iQ SYBR Green Supermix reagent (Bio-Rad). PCR was performed at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 50 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Threshold cycles (Ct) were measured, and with software provided by the manufacturer, the amounts of PCR products were calculated by using standard curves obtained from three different dilutions of input DNAs (10, 1, and 0.1%). The following primers were used: −450 to −298, 5′-CCCTCATTTCTGCTTTTTGG-3′ and 5′-TGGAGTCCACTGGGACAAAT-3′; −169 to −48, 5′-CCGCTGTTTACAAGGACACG-3′ and 5′-GGAAGTGCGCTCCGATTG-3′; −3 to +133, 5′-GGCTGGGACCTTGAGAGC-3′ and 5′-GTGCGCAAAAGCCCTGTC-3′; +284 to +403, 5′-CCGGATGTGCACTAAAATGG-3′ and 5′-AGGCTCGGTTTCAGGAGTTT-3′; +716 to +846, 5′-GGACGATCTGCACAAGATGA-3′ and 5′-TGCTGAGGTTGGTGTAAACG-3′; +1091 to +1198, 5′-CATCAAAGTGGAGCGCAAG-3′ and 5′-TTGAGCGTCTTCACCTTGTC-3′; +1485 to +1608, 5′-CCTTCCACCTCGACGTTTAC-3′ and 5′-CTCTTCCCCTCCCTGTTAAA-3′; +1895 to +2018, 5′-CCAGCTCAGTGCTGTTGGT-3′ and 5′-ATCCAACCCTGGAGATCTGG-3′; +2053 to +2177, 5′-AGCTGAAGGCAGGGTGCT-3′ and 5′-GGCAGAATCGGTCCTTGTAT-3′; +2256 to +2398, 5′-AAGGGGGCCGGGATTTT-3′ and 5′-CTAGGCGCCAGTGTCTTGAA-3′; +2644 to +2786, 5′-CAGCTGGGACACGTGGA-3′ and 5′-CCACTCACCCTACTGCCTGT-3′.

Modified ChIP with ligation-mediated PCR (LM-PCR).

ChIP assays were performed with some modifications. Cross-linked chromatin was suspended in modified sonication buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA). After a brief sonication, HaeIII (40 U) and PvuII (80 U) were added per 100 μl of cross-linked lysate. Partial digestion of chromatin was performed at 37°C for 30 min and terminated by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate to 1%. Following rotation for 1 h, samples were centrifuged and supernatants were used for immunoprecipitation. Coprecipitated DNAs and 1% of input DNAs in 5 μl of TE were subjected to LM-PCR as previously described (5). Briefly, DNA was blunt end ligated with the unidirectional linker consisting of two partially complementary oligonucleotides, LM-PCR.1 (5′-GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTGAATTC-3′) and LM-PCR.2 (5′-GAATTCAGATC-3′). Next, ligated DNA was subjected to a brief PCR amplification with LM-PCR.1 and the gene-specific primer ChIP.LM-PCR.GSP.2.upst (5′-AGCGCACTTCCGTGGCTGAC-3′). Lastly, the 32P-end-labeled primer ChIP.LM-PCR.GSP.3.upst (5′-TTCCGTGGCTGACTAGCGCGGTA-3′) was used for primer extension analysis of the PCR products.

Note that the first-strand synthesis step before linker ligation was omitted because HaeIII and PvuII both generate blunt-ended DNA fragments.

Potassium permanganate in vivo footprinting analysis.

Serum-starved HepG2 cells on a 10-cm dish were treated with 10 ml of 7.5 mM KMnO4 in phosphate-buffered saline for 45 s. After quick aspiration of the solution, reactions were quenched by adding 1 ml of TNESK (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1 mg/ml proteinase K) containing 0.4 M β-mercaptoethanol and incubated at 50°C for 1 h and then at 37°C overnight. Genomic DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, and DNA pellets were suspended in 200 μl of 1 M piperidine. After vigorous mixing for 15 min to suspend the pellets completely, samples were incubated at 90°C for 30 min, frozen quickly with liquid N2, and then dried for 90 min with a vacuum evaporator. Dried DNA pellets were suspended in 30 μl of distilled H2O and lyophilized again. This step was repeated. These steps were intended to remove residual piperidine completely. The samples were resuspended in TE to a final DNA concentration of 400 ng/μl and subjected to LM-PCR. Two primer sets were used to detect the promoter-proximal region of junB. The following gene-specific primers were used as primer set A for first-strand synthesis, PCR amplification, and primer extension labeling, respectively: LM-PCR.GSP.1, 5′-GTGCGCAAAAGCCCTGT-3′; LM-PCR.GSP.2, 5′-AAGCCCTGTCAGGCTTCCCGAG-3′; LM-PCR.GSP.3, 5′-TGTCAGGCTTCCCGAGCCCCCGT-3′. Likewise, the following primers were used as primer set B: LM-PCR.GSP.1.revB, 5′-CTGCGGTGACCGGACTG-3′; LM-PCR.GSP2.revB, 5′-TGGGTGCCTGGTCGCGCGT-3′; LM-PCR.GSP3.revB, TGGGTGCCTGGTCGCGCGTTCTC.

RNA interference (RNAi) analysis with lentiviral vectors.

For expression of short hairpin RNA against NELF-E, a double-stranded oligonucleotide was inserted downstream of the mouse U6 promoter (−315 to +1; GenBank accession number X06980) such that the following RNA sequence was expressed: 5′-GAUGGAGUCAGCAGAUCAGuucaagagaCUGAUCUGCUGACUCCAUCuu-3′ (the sequence in uppercase corresponds to positions 1020 to 1038 of the human NELF-E mRNA [accession no. NM_002904]). The expression cassette and a control U6 promoter sequence were subcloned into lentiviral vector pLenti6 (Invitrogen), and recombinant lentiviruses were produced according the manufacturer's instructions. For infection, HepG2 cells (9 × 105) were plated in 10-cm tissue culture dishes. On the following day (day 1), 1.5-ml aliquots of the lentiviral stock and Polybrene (final concentration, 6 μg/ml; Sigma) were added to dishes containing 4.5 ml of 10% FBS-DMEM, and on day 2, the medium was replaced with fresh medium. On day 3, the cells were passaged and divided into three 10-cm dishes, and on day 5, the cells were passaged again and divided into two six-well plates (5 × 105 cells in each well) and two 10-cm dishes (2 × 106 cells each). On day 6, the medium was replaced with 0.1% FBS-DMEM, and on day 7, the cells were stimulated with IL-6. The cells in six-well plates were used for real-time RT-PCR analysis or Western blot analysis, and the cells in 10-cm dishes were used for in vivo footprinting analysis. For ChIP assays, cells were plated on two 15-cm dishes (5 × 106 cells each) on day 5.

RESULTS

Spatiotemporal distribution of RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF over the junB gene.

To analyze the detailed mechanism by which DSIF and NELF function during IEG expression, we adopted the junB gene as a model because of its short length and high inducibility. In human hepatoma HepG2 cells, junB gene expression is rapidly and transiently induced following IL-6 stimulation. As shown in Fig. 1A, we observed that junB expression peaks 45 to 60 min after induction, which is consistent with a previous report (28). Expression was transient, and the junB mRNA level decreased 120 min after IL-6 stimulation.

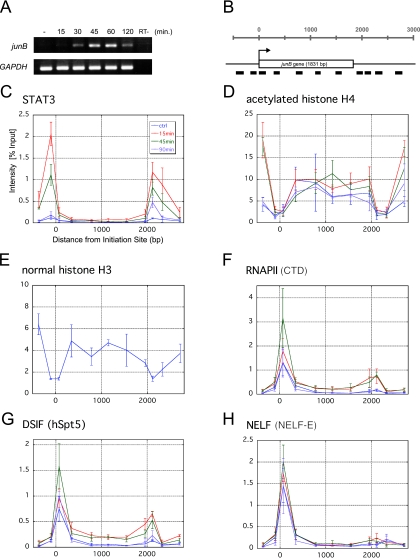

FIG. 1.

Spatiotemporal distribution of various factors over the junB gene. (A) RT-PCR analysis of junB gene expression. Total RNA was purified from serum-starved HepG2 cells, either left untreated or treated with 100 ng/ml IL-6 for the indicated times, and subjected to RT-PCR with two primer sets that amplify junB and GAPDH. As a control (RT−), the RT step was omitted. (B) Structure of the junB gene. Thick bars represent the positions of PCR amplicons used in ChIP assays. The transcribed region composed of a single exon is presented as an open box. (C to H) Quantification of the amount of DNA precipitated in the ChIP assay with various antibodies. HepG2 cells treated with 100 ng/ml IL-6 or left untreated were cross-linked with formaldehyde and immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. Note that the histone H3 ChIP in panel E was only done on the untreated sample. Real-time PCR was carried out with the primer sets that are shown in panel B. Percent recoveries are plotted against the distance from the transcription initiation site to the midpoint of each amplicon. Data are the mean ± the standard deviation from three independent experiments, each of which was performed in duplicate.

Before dissecting transcription elongation at the junB locus, we first analyzed two hallmarks of junB gene activation, STAT3 and histone H4 acetylation, by ChIP. STAT3 is a key transcriptional activator that, upon IL-6 stimulation, is phosphorylated, dimerizes, translocates into the nucleus, and binds to target gene promoters to induce IEG expression (6). A STAT3-binding site is located at −141 to −149 in the 5′-flanking region of junB. HepG2 cells were treated with IL-6 for various times or left untreated, and after cross-linking with 1% formaldehyde, chromatin extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-STAT3 and anti-acetylated histone H4 antibodies. Coprecipitated DNA was then purified and subjected to real-time PCR to quantify the amounts of 11 regions of the junB locus (Fig. 1B).

Whereas STAT3 was detected negligibly on the junB gene before induction, 15 min after IL-6 stimulation, STAT3 was specifically cross-linked to both the 5′- and 3′-flanking regions (Fig. 1C). The 3′ region was previously reported to be a putative downstream enhancer (7). STAT3 remained bound to the promoter and downstream enhancer regions for up to 45 min after induction and disappeared by 90 min. Concomitantly after induction, acetylation of histone H4 increased significantly in more distal 5′ and 3′ regions, while the transcribed region was modestly and constitutively acetylated (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, the levels of histone H4 acetylation, as well as those of histone H3, were quite low in the promoter and downstream enhancer regions (Fig. 1D and E). These findings, together with the previous report that these regions are hypersensitive to DNase I (21), suggest that the density of nucleosomes in these regions is constitutively low.

To investigate transcription elongation along the junB gene, we next mapped the distributions of RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF. ChIP with anti-RNAPII antibody (Fig. 1F) showed that RNAPII is efficiently recruited to the promoter region before induction. Fifteen minutes after IL-6 addition, RNAPII became cross-linked to the entire region of the gene, and maximal cross-linking was observed 45 min after induction. At 90 min, the distribution of RNAPII reverted to that of the uninduced state. These results are consistent with the idea that junB expression is controlled both before and after the PIC assembly step. We obtained very similar results with anti-hSpt5 antibody (Fig. 1G). A significant amount of hSpt5 was found associated with the promoter region before induction, and its cross-linking to the downstream regions was observed 15 min after induction. In contrast, the cross-linking pattern for NELF was different (Fig. 1H). Although NELF-E was cross-linked to the promoter region throughout the time course, it did not associate with the downstream regions appreciably, even after induction.

The above experiments revealed three important aspects of transcriptional regulation on the junB locus. First, RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF associate with the promoter region, but not with the downstream regions, before induction. Second, RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF accumulate in the promoter region after induction. Third, RNAPII and DSIF, but not NELF, associate with the downstream regions after induction. The first finding suggests that junB transcription is negatively regulated at the post-PIC assembly step before induction, and the second finding suggests that this negative regulation persists even after induction.

Association of RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF with the promoter-proximal transcribed region of junB.

Conventional ChIP analysis cannot distinguish between polymerases in the PIC and those paused in the promoter-proximal region. To obtain more precise information on the location of RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF, we performed a modified ChIP assay as previously described (4). Briefly, soluble chromatin was partially digested with HaeIII and PvuII, which cleave at positions +16 and +21 and at position +133 of the junB gene, respectively (Fig. 2A). After immunoprecipitation of the digested chromatin, coprecipitated DNAs and 1% of the input DNAs were subjected to LM-PCR analysis such that three digested genomic DNA fragments (fragments I, II, and III) were amplified. The three DNA fragments should be coimmunoprecipitated at different efficiencies, depending on the binding sites of the proteins of interest. For example, if RNAPII exclusively associates with the transcription initiation site, immunoprecipitation with anti-RNAPII antibody should lead to recovery of the three DNA fragments with equal efficiency. If RNAPII exclusively associates with the region between positions +21 and +133, only fragment III should be detected. Thus, a higher recovery of fragment III indicates the presence of RNAPII within the region between positions +21 and +133.

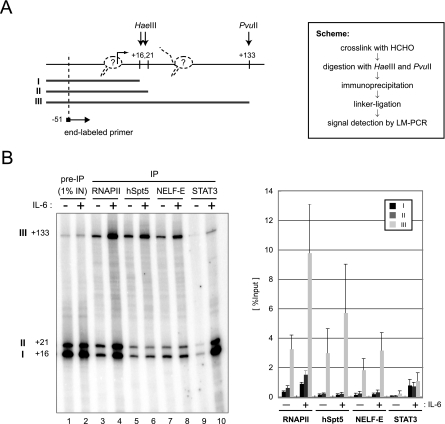

FIG. 2.

Association of RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF with the promoter-proximal transcribed region of junB. (A) Scheme of the assay. At the left, HaeIII and PvuII cleavage sites and the position of the end-labeled primer used to detect LM-PCR products are indicated by arrows. Numbers indicate relative positions from the transcription initiation site, based on the DataBase of Transcriptional Start Sites (http://dbtss.hgc.jp/). Possible positions of RNAPII are also shown (dotted line). At the right, the experimental scheme of the assay is shown. (B) After immunoprecipitation (IP) with the indicated antibodies, coprecipitated DNA was detected by LM-PCR. Numbers at left indicate the positions of cleavage by restriction enzymes. In the graph on the right, the recoveries of fragments I, II, and III are presented as percentages of the input. Signals were quantified with a Storm 860 image analyzer (Amersham Biosciences). Data are the mean ± the standard deviation from three independent experiments.

We compared untreated cells and cells stimulated with IL-6 for 45 min (Fig. 2B). As for RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF (lanes 3 to 8), fragment III was recovered at an efficiency severalfold higher than those of fragments I and II. Moreover, while the recovery of fragment III was clearly increased by IL-6 stimulation in all cases, the recovery of fragments I and II was increased significantly only in the case of RNAPII. As for STAT3 (lanes 9 and 10), which was used as a control, significantly more DNA fragments were recovered after induction. In contrast to the cases of RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF, the recoveries of the three DNA fragments were nearly identical. These results are fully consistent with the findings in Fig. 1 and suggest that the ChIP signals for RNAPII, DSIF, and NELF detected around the promoter region in Fig. 1 are largely attributable to their association with the transcribed region between positions +21 and +133, while STAT3 and some RNAPII also associate with regions upstream of position +16. It is likely that PICs, devoid of DSIF and NELF, and early elongation complexes containing DSIF and NELF are both present around the junB promoter region before induction and that the formation of PICs and early elongation complexes increases after induction.

RNAPII strongly accumulates at around position +50 of the junB gene.

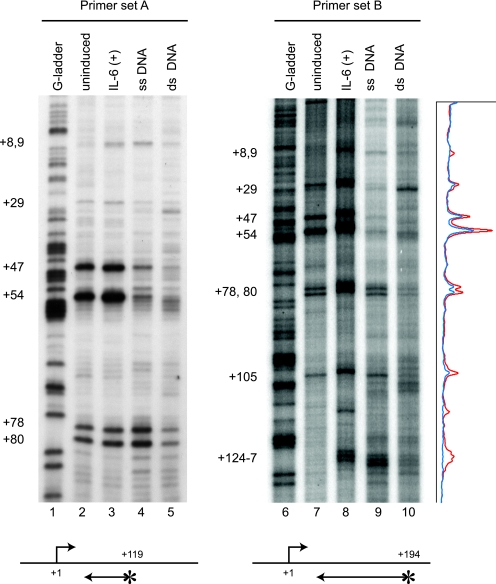

To determine the distribution of RNAPII over the junB promoter-proximal region at nucleotide resolution, we performed potassium permanganate (KMnO4) in vivo footprinting analysis. Because KMnO4 preferentially oxidizes thymidine residues in single-stranded DNA, transcription bubbles within elongating polymerases are detected by this analysis. Genomic DNA was prepared from KMnO4-treated cells and cleaved at oxidized sites with piperidine, and these sites were mapped by LM-PCR with two primer sets that are specific to the junB promoter-proximal region (Fig. 3). As a control, purified genomic DNA was treated with KMnO4 in vitro before and after heat denaturation in order to estimate the KMnO4 sensitivity of double-stranded and single-stranded DNAs, respectively (lanes 4, 5, 9, and 10). Consistent with the data in Fig. 1 and 2, transcription bubbles detected in the junB promoter-proximal region were similar in pattern before and after induction (lanes 2, 3, 7, and 8). Before induction, there were strong KMnO4-sensitive sites at positions +47 and +54 and minor sensitive sites at positions +29, +78, +80, and +105, the intensities of which were slightly increased by short-term (15 min) IL-6 treatment. T residues at positions +8, +9, and +124 to +127 were not sensitive to KMnO4 in unstimulated cells but became modestly sensitive after IL-6 stimulation. Similar results were obtained when IL-6 treatment was prolonged to 45 min (data not shown). These results indicate that a strong pause occurs at about position +50 of the junB gene before and after IL-6 induction.

FIG. 3.

RNAPII strongly accumulates at around position +50 of the junB gene. Control cells or cells stimulated by IL-6 for 15 min were treated with 7.5 mM KMnO4. Genomic DNA was purified, and unpaired thymine residues in transcription bubbles were mapped by in vivo footprinting with two primer sets. KMnO4 sensitivity in vivo was compared to the sensitivity of purified single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds) genomic DNA. Lanes 1 and 6 contain genomic DNA partially cleaved at guanine residues. Footprinting with primer set A (lanes 1 to 5) results in higher-resolution mapping of paused sites in a smaller region than that with primer set B (lanes 6 to 10). Signal intensity of the footprinting data for primer set B was obtained with a Storm 860 image analyzer and is presented on the right. The blue and red lines represent the results of uninduced and induced states, respectively. The positions of end-labeled primers are indicated by arrows with asterisks. The numbers on the left indicate the relative positions from the transcription initiation site.

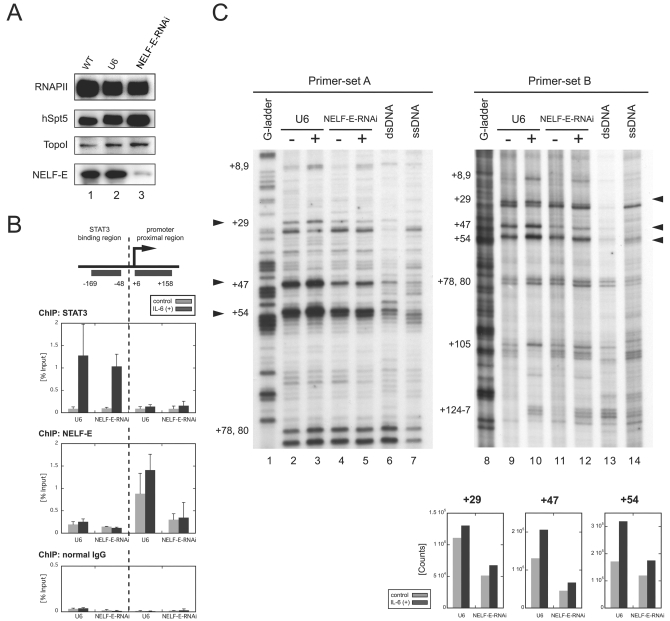

Transcriptional pausing is caused by NELF.

To investigate whether the polymerase pauses after IL-6 stimulation and whether pausing is indeed caused by NELF, we sought to reduce NELF activity in cells by RNAi. We chose to knock down NELF-E because its RNA recognition motif is essential for DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing in vitro (37). HepG2 cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing short hairpin RNA against NELF-E from the RNAPIII-driven U6 promoter (NELF-E-RNAi cells) or with a control vector bearing only the U6 promoter (U6 cells). Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A) indicated that the NELF-E protein level was dramatically reduced in NELF-E-RNAi cells 7 days after transduction compared to wild-type cells and U6 cells. The RNAPII, hSpt5, and TopoI protein levels were not affected significantly in NELF-E-RNAi cells.

FIG. 4.

Transcriptional pausing is caused by NELF. Cells were transduced with the NELF-E-knockdown RNAi construct (NELF-E-RNAi cells) or the control U6 promoter construct (U6 cells). All experiments were performed 7 days after transduction. (A) NELF-E knockdown selectively depletes NELF-E. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from wild-type (WT) HepG2 cells, U6 cells, and NELF-E-RNAi cells and blotted with the indicated antibodies. (B) Association of NELF-E with the junB promoter-proximal region is reduced in NELF-E-RNAi cells. NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells with or without IL-6 stimulation for 15 min were analyzed by ChIP with anti-STAT3 (top), anti-NELF-E (middle), and normal-mouse (bottom) antibodies. Recovery of the STAT3-binding region and the promoter-proximal region was quantified as for Fig. 1. Data are the mean ± the standard deviation from five (for U6) or three (NELF-E-RNAi) independent experiments. IgG, immunoglobulin G. (C) Promoter-proximal pausing is reduced in NELF-E-RNAi cells. NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells were analyzed before and after treatment with IL-6 for 15 min by in vivo footprinting as in Fig. 3. Signal counts of the footprint data on the right at positions +29, +47, and +54 were quantified by image analyzer and are shown at the bottom. dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA.

To confirm that NELF-E knockdown resulted in the reduction of its association with the junB promoter-proximal region, we examined NELF-E and STAT3, as a control, in NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells by ChIP. In U6 cells, NELF-E was detected in the promoter-proximal region at a higher occupancy after IL-6 induction, and NELF-E knockdown resulted in a significant reduction of the ChIP signals, as expected (Fig. 4B, middle). On the other hand, STAT3's association with the upstream STAT3-binding region was not significantly affected by NELF-E knockdown (Fig. 4B, top).

Next, we performed KMnO4 in vivo footprinting analysis with NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells (Fig. 4C). NELF-E knockdown resulted in a two- to threefold decrease in transcription bubbles at positions +29 and +47 both before and after induction, indicating that pausing was reduced at these sites. The signals at site +54 seemed to be less affected by the knockdown, possibly because of residual NELF (see Discussion). These results are consistent with the findings in Fig. 4B, and together they indicate that NELF activity is important for transcriptional pausing in the junB promoter-proximal region both before and after induction.

DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing attenuates expression of junB and other IEGs.

We then investigated the role of NELF in junB expression by quantifying the mRNA level by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 5A, left). Although the junB mRNA level reached its peak at 60 min after induction in both NELF-E-RNAi and U6 cells, NELF-E knockdown resulted in a reproducible twofold increase in the junB mRNA level both before and after induction. In contrast, the GAPDH mRNA level was not affected by NELF-E knockdown (Fig. 5A, right). The increase in junB expression was also observed at the protein level. Western blot analysis showed that NELF-E knockdown resulted in a twofold increase in the JunB protein level both before and after induction (Fig. 5B). Next, we examined whether or not NELF-E knockdown affects the IL-6-STAT3 signaling pathway. STAT3 is known to be activated by phosphorylation on Tyr705 and Ser727 (1, 43). As shown in Fig. 5C, STAT3 phosphorylation increased transiently after IL-6 treatment and was not appreciably affected by NELF-E knockdown. These results indicate that NELF directly downregulates both basal and activated levels of transcription of the junB gene. Moreover, the similar effects of NELF-E knockdown on both the mRNA and protein levels of junB suggest that NELF is not involved in processing, export, and translation of the mRNA.

Like junB, c-fos and tis-11 are IEGs that are controlled by STAT3 and are rapidly induced by IL-6 (16, 40). Moreover, c-fos is thought to be regulated in the transcription elongation phase (23). We therefore examined whether NELF is also involved in the regulation of these genes. As shown in Fig. 6, NELF-E knockdown resulted in a two- to threefold enhancement of the mRNA levels of c-fos and tis-11 both before and after IL-6 induction. These results indicate that c-fos and tis-11 are subject to negative regulation by NELF as well.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have provided insights into the mechanism that regulates IEG expression by transcription elongation factors DSIF and NELF. We provided evidence that DSIF and NELF downregulate junB gene expression before induction, by causing promoter-proximal pausing of RNAPII at around position +50. Moreover, DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing on junB persists after induction and acts to reduce the maximal level of its expression. Two other IEGs, c-fos and tis-11, but not the housekeeping gene GAPDH, are subject to a similar negative regulation, suggesting an important role for NELF in the regulation of a subset of inducible genes.

Paused polymerases have been identified at several loci, of which Drosophila hsp70 is the best studied. Pausing at hsp70 occurs between positions +20 and +40 of the transcribed region and is thought to involve DSIF and NELF (33, 34). In addition, the promoter region of hsp70 is known to be decondensed in the absence of heat shock (8). Several lines of evidence suggest that the junB promoter region has a similar chromatin structure. We have shown that the promoter and downstream enhancer regions are not immunoprecipitated efficiently by anti-acetylated histone H4 and anti-histone H3 antibodies (Fig. 1D and E). Moreover, both regions are hypersensitive to DNase I (21, 22). Such a decondensed chromatin structure probably makes the promoter region accessible to the basal transcription machinery and facilitates PIC assembly and transcription initiation, and then transcription is subject to negative regulation by DSIF and NELF.

Although DSIF and NELF were biochemically identified on the basis of the ability to stall RNAPII movement along a DNA template, it is not well understood when and where these proteins function on the genome of living cells. At the human junB locus, DSIF and NELF likely induce transcriptional pausing in the promoter-proximal region. It appears that DSIF also travels downstream with RNAPII following induction (Fig. 1), an observation that is consistent with another biochemical activity of DSIF, the promotion of elongation (32). We assume that pausing before induction acts to reduce unwanted “leaky” expression of junB. Our results showed, however, that depletion of NELF does not lead to full activation of junB in an uninduced state. Other processes occurring after induction, such as activator-dependent recruitment of more RNAPII to the promoter, may also be required to fully activate the gene. Alternatively, residual NELF activity after the knockdown may obscure true phenotypic effects. In this regard, it is noteworthy that a substantial amount of NELF-E remained associated with the junB promoter-proximal region after its knockdown in spite of a large overall decrease in the level of its protein (Fig. 4). This apparent discrepancy may be explained by possible preferential depletion of a free pool of NELF.

Importantly, our study shows that DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing on junB persists and attenuates junB expression even after induction. This finding contrasts with the observation that on Drosophila hsp70, heat shock causes dissociation of NELF and alleviation of promoter-proximal pausing (34). In the case of some human estrogen-responsive genes, it is reported that NELF attenuates the activated level of transcription (3), similar to what we observed for junB and other IEGs. Before induction, however, RNAPII and NELF are not appreciably associated with the estrogen-responsive genes (3). Thus, DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing at the junB locus is partly similar but not identical to those found on Drosophila hsp70 and human estrogen-responsive genes.

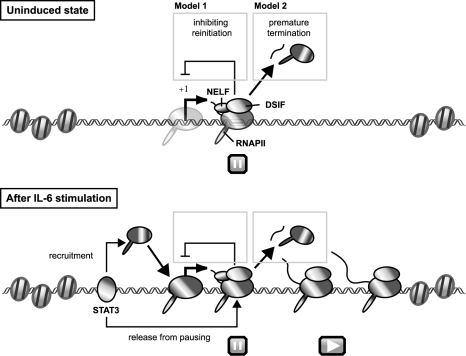

On the basis of these results, we propose the following model for transcriptional regulation of junB by DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing (Fig. 7). In an uninduced state, DSIF and NELF cause RNAPII pausing at around position +50 of the promoter-proximal region, where chromatin structure is decondensed and permissive for PIC assembly and transcription initiation. Immediately after IL-6 stimulation, the transcriptional activator STAT3 binds to both the promoter and 3′ enhancer regions and increases the efficiency of transcription elongation, allowing the polymerase to reach the 3′ end of the gene. STAT3 also recruits more RNAPII to the promoter region. The enhancement of transcription elongation by STAT3 may be mediated by P-TEFb or other proteins having elongation activation activity. From a number of in vitro and/or in vivo studies, it has been shown that P-TEFb, FACT, TFIIS, TFIIF, and the capping enzyme are capable of reversing transcriptional repression imposed by DSIF and NELF (2, 14, 19, 25, 30). However, DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing persists and continues to attenuate junB expression. We provide two possible explanations as to how transcriptional pausing attenuates the level of mRNA expression. First, RNAPII paused in the promoter-proximal region may prevent transcription reinitiation by posing an obstacle to progression of the second polymerase, which we detected in Fig. 2. Second, pausing may eventually lead to premature termination of transcription. DSIF and NELF induce slowdown or pausing but not termination of polymerases in vitro (25, 38). When DSIF and NELF cause a prolonged pausing of polymerases in living cells, however, other proteins, such as the transcription termination factor Pcf11 (42), may cause premature termination. In either case, pausing acts as a rate-limiting step to reduce the maximal level of target gene expression.

FIG. 7.

Model for transcriptional regulation of junB by DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing. Before induction, DSIF and NELF cause RNAPII pausing in the promoter-proximal region of junB, where chromatin structure is decondensed and permissive for PIC assembly (for details, see Discussion). After IL-6 stimulation, STAT3 binds to the promoter and 3′ enhancer regions and increases the efficiency of both PIC assembly and transcription elongation, allowing the polymerase to reach the 3′ end of the gene, possibly by recruiting P-TEFb or other proteins with elongation activation activity. However, DSIF- and NELF-mediated pausing persists in the promoter-proximal region and acts to reduce the maximal level of its expression. Two possible mechanisms for attenuation by NELF are presented.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sachiko Okabe, Michiko Tatsuno, Junko Kato, Sachiko Okamoto, and Tetsu Yung for technical assistance and manuscript preparation and members of the Handa lab for helpful suggestions. We also thank George Orphanides for providing a ChIP protocol.

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (to T.W. and H.H.) and a grant from NEDO (to H.H.). This study was also supported in part by the Tokyo Tech. Award for Challenging Research to T.W. and a grant from the 21st Century COE Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. M.A. is a research fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, K., M. Hirai, K. Mizuno, N. Higashi, T. Sekimoto, T. Miki, T. Hirano, and K. Nakajima. 2001. The YXXQ motif in gp130 is crucial for STAT3 phosphorylation at Ser727 through an H7-sensitive kinase pathway. Oncogene 20:3464-3474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adelman, K., M. T. Marr, J. Werner, A. Saunders, Z. Ni, E. D. Andrulis, and J. T. Lis. 2005. Efficient release from promoter-proximal stall sites requires transcript cleavage factor TFIIS. Mol. Cell 17:103-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiyar, S. E., J. L. Sun, A. L. Blair, C. A. Moskaluk, Y. Z. Lu, Q. N. Ye, Y. Yamaguchi, A. Mukherjee, D. M. Ren, H. Handa, and R. Li. 2004. Attenuation of estrogen receptor alpha-mediated transcription through estrogen-stimulated recruitment of a negative elongation factor. Genes Dev. 18:2134-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrulis, E. D., E. Guzman, P. Doring, J. Werner, and J. T. Lis. 2000. High-resolution localization of Drosophila Spt5 and Spt6 at heat shock genes in vivo: roles in promoter proximal pausing and transcription elongation. Genes Dev. 14:2635-2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 6.Bromberg, J., and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 2000. The role of STATs in transcriptional control and their impact on cellular function. Oncogene 19:2468-2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, R. T., I. Z. Ades, and R. P. Nordan. 1995. An acute phase response factor/NF-κB site downstream of the junB gene that mediates responsiveness to interleukin-6 in a murine plasmacytoma. J. Biol. Chem. 270:31129-31135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costlow, N., and J. T. Lis. 1984. High-resolution mapping of DNase I-hypersensitive sites of Drosophila heat shock genes in Drosophila melanogaster and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:1853-1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo, S., Y. Yamaguchi, S. Schilbach, T. Wada, J. Lee, A. Goddard, D. French, H. Handa, and A. Rosenthal. 2000. A regulator of transcriptional elongation controls vertebrate neuronal development. Nature 408:366-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartzog, G. A., T. Wada, H. Handa, and F. Winston. 1998. Evidence that Spt4, Spt5, and Spt6 control transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 12:357-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs-Helber, S. M., R. M. Abutin, C. Tian, M. Bondurant, A. Wickrema, and S. T. Sawyer. 2002. Role of JunB in erythroid differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:4859-4866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krumm, A., T. Meulia, M. Brunvand, and M. Groudine. 1992. The block to transcriptional elongation within the human c-myc gene is determined in the promoter-proximal region. Genes Dev. 6:2201-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lis, J. 1998. Promoter-associated pausing in promoter architecture and postinitiation transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:347-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandal, S. S., C. Chu, T. Wada, H. Handa, A. J. Shatkin, and D. Reinberg. 2004. Functional interactions of RNA-capping enzyme with factors that positively and negatively regulate promoter escape by RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:7572-7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathas, S., M. Hinz, I. Anagnostopoulos, D. Krappmann, A. Lietz, F. Jundt, K. Bommert, F. Mechta-Grigoriou, H. Stein, B. Dorken, and C. Scheidereit. 2002. Aberrantly expressed c-Jun and JunB are a hallmark of Hodgkin lymphoma cells, stimulate proliferation and synergize with NF-κB. EMBO J. 21:4104-4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima, K., and R. Wall. 1991. Interleukin-6 signals activating junB and TIS11 gene transcription in a B-cell hybridoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:1409-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narita, T., Y. Yamaguchi, K. Yano, S. Sugimoto, S. Chanarat, T. Wada, D. K. Kim, J. Hasegawa, M. Omori, N. Inukai, M. Endoh, T. Yamada, and H. Handa. 2003. Human transcription elongation factor NELF: identification of novel subunits and reconstitution of the functionally active complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1863-1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oshima, S., T. Nakamura, S. Namiki, E. Okada, K. Tsuchiya, R. Okamoto, M. Yamazaki, T. Yokota, M. Aida, Y. Yamaguchi, T. Kanai, H. Handa, and M. Watanabe. 2004. Interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2 distinctively up-regulate gene expression and production of interleukin-7 in human intestinal epithelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6298-6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palangat, M., D. B. Renner, D. H. Price, and R. Landick. 2005. A negative elongation factor for human RNA polymerase II inhibits the anti-arrest transcript-cleavage factor TFIIS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:15036-15041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Passegue, E., E. F. Wagner, and I. L. Weissman. 2004. JunB deficiency leads to a myeloproliferative disorder arising from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell 119:431-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phinney, D. G., C. L. Keiper, M. K. Francis, and K. Ryder. 1994. Quantitative analysis of the contribution made by 5′-flanking and 3′-flanking sequences to the transcriptional regulation of junB by growth factors. Oncogene 9:2353-2362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phinney, D. G., S. W. Tseng, and K. Ryder. 1995. Complex genetic organization of junB: multiple blocks of flanking evolutionarily conserved sequence at the murine and human junB loci. Genomics 28:228-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plet, A., D. Eick, and J. M. Blanchard. 1995. Elongation and premature termination of transcripts initiated from c-fos and c-myc promoters show dissimilar patterns. Oncogene 10:319-328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasmussen, E. B., and J. T. Lis. 1995. Short transcripts of the ternary complex provide insight into RNA polymerase II elongational pausing. J. Mol. Biol. 252:522-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renner, D. B., Y. Yamaguchi, T. Wada, H. Handa, and D. H. Price. 2001. A highly purified RNA polymerase II elongation control system. J. Biol. Chem. 276:42601-42609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roeder, R. G. 2005. Transcriptional regulation and the role of diverse coactivators in animal cells. FEBS Lett. 579:909-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sims, R. J., III, R. Belotserkovskaya, and D. Reinberg. 2004. Elongation by RNA polymerase II: the short and long of it. Genes Dev. 18:2437-2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sjin, R. M., K. A. Lord, A. Abdollahi, B. Hoffman, and D. A. Liebermann. 1999. Interleukin-6 and leukemia inhibitory factor induction of JunB is regulated by distinct cell type-specific cis-acting elements. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28697-28707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soutoglou, E., and I. Talianidis. 2002. Coordination of PIC assembly and chromatin remodeling during differentiation-induced gene activation. Science 295:1901-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wada, T., G. Orphanides, J. Hasegawa, D. K. Kim, D. Shima, Y. Yamaguchi, A. Fukuda, K. Hisatake, S. Oh, D. Reinberg, and H. Handa. 2000. FACT relieves DSIF/NELF-mediated inhibition of transcriptional elongation and reveals functional differences between P-TEFb and TFIIH. Mol. Cell 5:1067-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wada, T., T. Takagi, Y. Yamaguchi, A. Ferdous, T. Imai, S. Hirose, S. Sugimoto, K. Yano, G. A. Hartzog, F. Winston, S. Buratowski, and H. Handa. 1998. DSIF, a novel transcription elongation factor that regulates RNA polymerase II processivity, is composed of human Spt4 and Spt5 homologs. Genes Dev. 12:343-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wada, T., T. Takagi, Y. Yamaguchi, D. Watanabe, and H. Handa. 1998. Evidence that P-TEFb alleviates the negative effect of DSIF on RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription in vitro. EMBO J. 17:7395-7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu, C. H., C. Lee, R. Fan, M. J. Smith, Y. Yamaguchi, H. Handa, and D. S. Gilmour. 2005. Molecular characterization of Drosophila NELF. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:1269-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, C. H., Y. Yamaguchi, L. R. Benjamin, M. Horvat-Gordon, J. Washinsky, E. Enerly, J. Larsson, A. Lambertsson, H. Handa, and D. Gilmour. 2003. NELF and DSIF cause promoter proximal pausing on the hsp70 promoter in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 17:1402-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada, T., Y. Yamaguchi, N. Inukai, S. Okamoto, T. Mura, and H. Handa. 2006. P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of hSpt5 C-terminal repeats is critical for processive transcription elongation. Mol. Cell 21:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi, Y., J. Filipovska, K. Yano, A. Furuya, N. Inukai, T. Narita, T. Wada, S. Sugimoto, M. M. Konarska, and H. Handa. 2001. Stimulation of RNA polymerase II elongation by hepatitis delta antigen. Science 293:124-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaguchi, Y., N. Inukai, T. Narita, T. Wada, and H. Handa. 2002. Evidence that negative elongation factor represses transcription elongation through binding to a DRB sensitivity-inducing factor/RNA polymerase II complex and RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2918-2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamaguchi, Y., T. Takagi, T. Wada, K. Yano, A. Furuya, S. Sugimoto, J. Hasegawa, and H. Handa. 1999. NELF, a multisubunit complex containing RD, cooperates with DSIF to repress RNA polymerase II elongation. Cell 97:41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamaguchi, Y., T. Wada, D. Watanabe, T. Takagi, J. Hasegawa, and H. Handa. 1999. Structure and function of the human transcription elongation factor DSIF. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8085-8092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang, E., L. Lerner, D. Besser, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 2003. Independent and cooperative activation of chromosomal c-fos promoter by STAT3. J. Biol. Chem. 278:15794-15799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye, Q., Y. F. Hu, H. Zhong, A. C. Nye, A. S. Belmont, and R. Li. 2001. BRCA1-induced large-scale chromatin unfolding and allele-specific effects of cancer-predisposing mutations. J. Cell Biol. 155:911-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, Z., and D. S. Gilmour. 2006. Pcf11 is a termination factor in Drosophila that dismantles the elongation complex by bridging the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II to the nascent transcript. Mol. Cell 21:65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhong, Z., Z. Wen, and J. E. Darnell, Jr. 1994. Stat3: a STAT family member activated by tyrosine phosphorylation in response to epidermal growth factor and interleukin-6. Science 264:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]