Abstract

The Ntr1 and Ntr2 proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been reported to interact with proteins involved in pre-mRNA splicing, but their roles in the splicing process are unknown. We show here that they associate with a postsplicing complex containing the excised intron and the spliceosomal U2, U5, and U6 snRNAs, supporting a link with a late stage in the pre-mRNA splicing process. Extract from cells that had been metabolically depleted of Ntr1 has low splicing activity and accumulates the excised intron. Also, the level of U4/U6 di-snRNP is increased but those of the free U5 and U6 snRNPs are decreased in Ntr1-depleted extract, and increased levels of U2 and decreased levels of U4 are found associated with the U5 snRNP protein Prp8. These results suggest a requirement for Ntr1 for turnover of the excised intron complex and recycling of snRNPs. Ntr1 interacts directly or indirectly with the intron release factor Prp43 and is required for its association with the excised intron. We propose that Ntr1 promotes release of excised introns from splicing complexes by acting as a spliceosome receptor or RNA-targeting factor for Prp43, possibly assisted by the Ntr2 protein.

The excision of introns from precursor mRNAs (pre-mRNAs) occurs by two consecutive transesterification reactions in the spliceosome, a large and highly dynamic ribonucleoprotein complex (9). These chemical reactions are likely catalyzed by small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) that exist within small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs), but non-snRNP proteins also play essential roles such as conferring specificity, checking the fidelity of the process, and regulating conformational rearrangements in the spliceosome (8, 34, 42). Five snRNPs, called U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6, assemble on the substrate pre-mRNA to form the spliceosome. First, the U1 snRNP binds at the 5′ splice site, followed by the U2 snRNP at the branch point, and then the U4, U5, and U6 snRNPs, in the form of a U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP, join the assembling complex. Activation of the assembled spliceosome requires dynamic remodeling of an intricate network of RNA-RNA and RNA-protein interactions within the spliceosome such that the U1 and U4 snRNPs are released. Concomitantly, the Prp19-associated complex of proteins (nineteen complex or NTC) (27, 28, 35, 36) associates with the spliceosome, remodeling the U5 snRNP (24, 25) and stabilizing interactions of the U5 and U6 snRNAs with the pre-mRNA (10, 11) prior to the first catalytic step of splicing.

Upon completion of the splicing reaction, the spliced exon RNA (mRNA) is released and the postsplicing ribonucleoprotein complex dissociates in an active process that involves two members of the ATP-dependent DExH box RNA helicase family, Prp22 and Prp43 (3, 26, 32). Prp22 is needed for release of the spliced exons (32, 43), while Prp43 is required for disassembly of the spliceosome and release of the excised intron in its branched, lariat form (26). The U4 snRNP reassociates with the U6 snRNP (31, 41) to form the U4/U6 di-snRNP that will then join the U5 snRNP to form the U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP once more.

Although many protein components of the splicing machinery have been identified through their physical or genetic interactions with known splicing factors, the functions of a large number of these remain to be determined. For example, the name SPP382 (S. Pandit and B. C. Rymond, unpublished results; http://db.yeastgenome.org/cgi-bin/locus.pl?locus=spp382) was given to Saccharomyces cerevisiae open reading frame YLR424W to indicate its ability to suppress the prp38-1 mutation that causes a defect in spliceosome maturation (45); however, the function of the Spp382 protein is unknown. Spp382 has been reported to associate directly or indirectly with many protein components of the splicing machinery, including Prp43 and components of the U5 snRNP (1, 7, 13, 16), and recently the name Ntr1 (nineteen complex related) was proposed because of its interaction with the NTC (38). In addition, Spp382/Ntr1 interacts with Ykr022c/Ntr2 (16, 17, 38, 39).

We demonstrate here that Ntr1 and Ntr2 are spliceosome associated and coprecipitate mainly excised intron from an in vitro splicing reaction mixture. Under nonsplicing conditions, Ntr1 and Ntr2 coprecipitate the U2, U5, and U6 snRNAs. Northern and microarray analyses show increased levels of pre-mRNAs in cells depleted of Ntr1, and in vitro, Ntr1-depleted extract has low splicing activity and accumulates excised intron in a postsplicing complex that includes Prp8 and Cef1. Glycerol gradient analysis of Ntr1-depleted extract suggests a defect in recycling snRNPs, and the U5 snRNP protein Prp8 is shown by immunoprecipitation to be associated with eightfold more U2 snRNA and with U6 snRNA that is not complexed with U4 snRNA, supporting its accumulation in the U2/U5/U6 postsplicing complex. The intron release factor Prp43 cofractionates with Ntr1 and Ntr2, and in the absence of Ntr1, Prp43 is unable to associate with spliceosomes to release the excised intron. These results complement and extend the recently reported results of Tsai et al. (38), demonstrating that Ntr1 and Ntr2 function in the Prp43-mediated release of the excised intron. We propose that Ntr1 acts as a spliceosome receptor or RNA-targeting factor to promote interaction of Prp43 with the excised intron, possibly assisted by the Ntr2 protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and plasmids.

The S. cerevisiae strains and plasmids used in this work are described in Table 1, and the oligonucleotides used are described in Table 2. For metabolic depletion of Ntr1, cultures of KL4G or KL4G2T were grown in YPGR (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% galactose, 2% raffinose) medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5, spun down, washed with YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, 2% glucose), spun down, resuspended in the original culture volume of YPD, and grown for 10 h or as indicated (with addition of fresh YPD to keep the cells in log phase). Yeast transformation was performed as described previously (14). Strains KL2T, KL4T, KL4G, and KL4G2T were generated from BMA38a (1) by one-step PCR transformation by using plasmid DNAs as templates (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Plasmids and yeast strains used in this study

| Plasmid or strain | Purpose or genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pFA6a-kanMX6-PGAL1-3HA | PCR template for KanMx6-PGAL1-3HA insertion | 23 |

| pBS1479 | PCR template for TAP tag with TRP1 marker | 30 |

| pBS1539 | PCR template for TAP tag with URA3 marker | 30 |

| pET16-PRP43T123A | pET16b-based plasmid for production of Prp43T123A protein in E. coli | 26 |

| pGEX4T-2-424 | pGEX4T-2-based plasmid for production of Ntr1 protein in E. coli | This work |

| Strains | ||

| BMA38a | MATahis3Δ200 leu2-3,112 ura3-1 trp1Δ1 ade2-1 can1-100 | 5 |

| RG8T | PRP8-TAP-TRP1, otherwise same as BMA38a | 7 |

| KL4T | NTR1-TAP-TRP1, otherwise same as BMA38a | This work |

| KL2T | NTR2-TAP-URA3, otherwise same as BMA38a | This work |

| KL4G | KanMX6-PGAL1-3HA-NTR1, otherwise same as BMA38a | This work |

| KL4G2T | KanMX6-PGAL1-3HA-NTR1 NTR2-TAP-URA3, otherwise same as BMA38a | This work |

TABLE 2.

Deoxyoligonucleotides used in this study

| snRNA | Probe |

|---|---|

| U1 | CACGCCTTCCGCGCCGT |

| U2 | CTACACTTGATCTAAGCCAAAAG |

| U3 | UUAUGGGACUUGUU |

| U4 | AGGTATTCCAAAAATTCCC |

| U5 | AAGTTCCAAAAAATATGGCAAGC |

| U6 | ATCTCTGTATTGTTTCAAATTGACCAA |

| Oligonucleotides for C-terminal NTR2 TAP tagging | |

| F-YKR022C-TAP | TTGGAAAAATCTAAAGCAAGCCTAATAAATAAGCTCATTGGTAACTCCATGGAAAAGAGAAG |

| R-YKR022C-TAP | TTTTTAATAGTACAGCGATTAAAAAAATAACATGATTAACGTTCATACGACTCACTATAGGG |

| Oligonucleotides for PCR amplification of NTR1 from genomic DNA (BMA38a) and cloning into pGEX4T-2 via SalI and NotI restriction sites | |

| F-YLR424W-aa2 | AAAAG TCGACCGAGGATTCGGACTCCAACAC |

| R-YLR424W-aa709 | AAAAGCGGCCGCACTAGAGGTCAAGGGCCCATA |

| Oligonucleotides used for C-terminal NTR1 TAP tagging | |

| F-YLR424W-TAP | TCCAGTGGGACCTTTAAGCCAATTTATTTATGGGCCCTTGACCTCTCCATGGAAAAGAGAAG |

| R-YLR424W-TAP | ATATATAAATCGTGCCTATCTCACCTCTTTTATAGGTACTTTCTATACGACTCACTATAGGG |

| Oligonucleotides for N-terminal NTR1 PGAL1 promoter and triple HA tagging | |

| F1-YLR424W | CAACCGAGAGAGGTCGAAGAACTTAAGCCTTCAGTACGCCAAAACGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC |

| R2-YLR424W | TTTGAAAAAGAACTTTTTATCTGTGTTGGAGTCCGAATCCTCCATGCACTGAGCAGCGTAATCTG |

Splicing extract preparation and in vitro splicing analysis.

Preparation of whole-cell yeast extracts was performed as described previously (40). In vitro splicing reaction mixtures were prepared as described previously (22). Plasmid p283, which contains part of the yeast ACTI gene, was transcribed in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase and [α-32P]ATP to produce a uniformly labeled splicing substrate (29).

Glycerol gradient analysis.

For glycerol gradient analysis (essentially as described in reference 4), 80 μl of splicing extract (without added ATP or pre-mRNA) was diluted to 200 μl with 120 μl of GG buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA) and layered onto an 11-ml 10 to 30% glycerol gradient containing GG buffer. After centrifugation at 37,000 rpm for 17 h in an SW40 Ti rotor (Beckman) at 4°C, 400-μl fractions were collected and stored at −70°C. Alternate fractions were analyzed by Western or Northern blotting.

Immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (37), with IPP150 buffer (6 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40) and with immunoglobulin G (IgG) agarose (Sigma)-, antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) agarose (mouse anti-HA [F-7]; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-His agarose (rabbit anti-His [H-15]; Santa Cruz Biotechnology)-, or protein A-Sepharose-bound antibodies, i.e., anti-Prp8 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (raised against a peptide corresponding to amino acids 2 to 34 of Prp8; this lab), anti-HA antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), affinity-purified anti-Prp43 antibodies raised against a peptide corresponding to amino acids 714 to 727 or obtained as a gift from Y. Henry (20). For immunoprecipitation of spliceosomes, splicing reaction mixtures (10 μl for splicing activity or 50 μl for immunoprecipitation) were incubated at 23°C for 25 min and the reaction products were fractionated on a 7% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel and visualized by autoradiography of the dried gel. For immunoprecipitation of snRNPs (see Fig. 1A and 3C), splicing extracts were used but without addition of ATP or pre-mRNA.

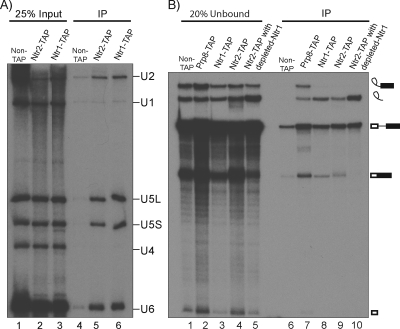

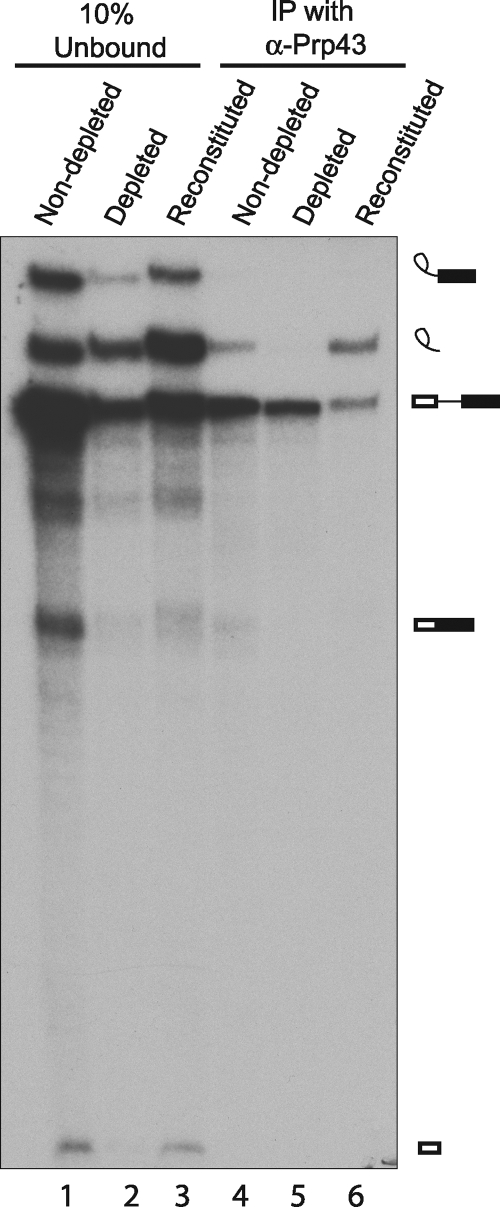

FIG. 1.

Ntr1 and Ntr2 associate with snRNPs and excised intron RNA. (A) Coprecipitation of snRNAs with Ntr1 and Ntr2. Splicing extracts (50 μl) with nontagged proteins (BMA38a; lane 4), Ntr2-TAP (KL2T; lane 5), or Ntr1-TAP (KL4T; lane 6) were mixed with an equal volume of precipitation buffer containing IgG-agarose beads and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were washed in buffer containing 150 mM NaCl and deproteinized, and the RNAs were precipitated, fractionated in an 8% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel, blotted, and probed for U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs. Total RNA extracted from 12.5 μl of each extract is shown in lanes 1 to 3. (B) Coprecipitation of splicing complexes by Ntr1 and Ntr2. Splicing extracts derived from cultures with nontagged proteins (BMA38a; lanes 1 and 6), Prp8-TAP (RG8T; lanes 2 and 7), Ntr1-TAP (KL4T; lanes 3 and 8), Ntr2-TAP (KL2T; lanes 4 and 9), and Ntr2-TAP with HA-Ntr1 depleted (KL4G2T cells grown in glucose for 10 h; lanes 5 and 10) were incubated under splicing conditions in vitro (60-μl total volume) with 32P-labeled ACT1 RNA as the substrate. The reactions were stopped after 25 min, and 10-μl volumes were removed as splicing controls (not shown). The remaining 50-μl volumes were mixed with IgG-agarose beads and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. Beads were washed in buffer containing IPP150 and deproteinized, and the RNAs were precipitated. The unbound samples were also deproteinized, and 20% aliquots were analyzed (lanes 1 to 5) alongside the precipitates (lanes 6 to 10) by fractionation in a 7% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel and autoradiography. The various RNA species are indicated diagrammatically to the right of panel B, with rectangles representing exons, a thin line representing the intron, and a lariat loop representing the branched form of the intron following the first catalytic step of splicing. IP, immunoprecipitation.

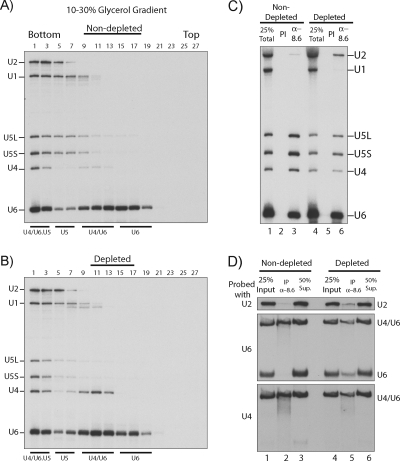

FIG. 3.

Depletion of Ntr1 leads to a redistribution of snRNP complexes. To examine the profile of snRNP distribution, non-Ntr1-depleted (A) and Ntr1-depleted (B) cell extracts (no added ATP or pre-mRNA) were centrifuged through 10 to 30% glycerol gradients and RNAs were extracted from alternate fractions and analyzed by Northern blotting with hybridization with probes for U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 snRNAs. The sedimentation of snRNP complexes is indicated. In addition to U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNPs and U5 snRNPs, fractions 1 to 7 may contain some endogenous spliceosome and postsplicing complexes. (C) Coprecipitation of snRNAs by anti-Prp8 antibodies in extracts from Ntr1-depleted (lanes 4 to 6) or nondepleted (lanes 1 to 3) cells. RNAs were analyzed by fractionation in a 6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel and Northern blotting. Preimmune (PI) serum was used as a background control. (D) Same as panel C, but the precipitated snRNAs were analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis as described previously (41). IP, immunoprecipitation.

Western blotting.

Proteins were resolved in Novex NuPAGE 4 to 12% bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), electroblotted to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Hybond-P; Amersham Bioscience), probed with primary antibodies, and detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies and ECL reagents (Amersham Bioscience).

Northern analysis of RNAs.

RNAs were deproteinized by sodium dodecyl sulfate-proteinase K treatment, followed by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and fractionated in a 6% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel. The sn(o)RNAs were detected by Northern analysis with end-labeled deoxyoligonucleotides complementary to U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6 or U3 (Table 2). The amounts of radioactivity in RNA bands were quantified with a Storm 860 PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). The amounts in precipitates were normalized against the input amounts.

RESULTS

Ntr1 and Ntr2 proteins associate with a postsplicing intron-containing complex.

To investigate whether the Ntr1 or Ntr2 protein associates with spliceosomal snRNPs, we tested the ability of C-terminally tandem affinity procedure (TAP)-tagged Ntr1 (Ntr1-TAP) or Ntr2 (Ntr2-TAP) protein to coprecipitate the U1, U2, U4, U5, or U6 snRNA. As shown in Fig. 1A, both Ntr2-TAP and Ntr1-TAP, when immunoprecipitated in the presence of 150 mM salt, coprecipitated the U2, U5 (L and S), and U6 snRNAs but no U1 or U4 snRNA above the background (compare lanes 5 and 6 with lane 4). This indicates that each of these proteins associates with a significant amount of the U2, U5, and U6 snRNPs (approximately 20% of the U2 and U5 snRNPs were precipitated; note that U6 snRNP is normally present in excess over the other spliceosomal snRNPs). To determine directly whether the Ntr1 or Ntr2 protein interacts with spliceosomes, the association of the TAP-tagged proteins with ACT1 substrate RNA or the intermediates or products of its splicing in vitro was tested by immunoprecipitation. As previously reported (37), the U5 snRNP protein Prp8 coprecipitated unspliced RNA, as well as intermediates and products of the splicing reaction (Fig. 1B, lane 7). In contrast, Ntr1-TAP and Ntr2-TAP coprecipitated the excised intron preferentially over the other RNA species (Fig. 1B, lanes 8 and 9). The U2, U5, and U6 snRNPs have been found in a postspliceosome complex that contains the excised intron, following release of the spliced exons in a HeLa cell splicing reaction mixture (19). Thus, the association of the Ntr1 and Ntr2 proteins with U2, U5, and U6 snRNPs and with excised intron RNA most likely indicates their association with a postsplicing intron-containing complex and suggests either that they may be absent at earlier stages of the splicing process or that the TAP tag was masked within earlier spliceosome complexes.

Depletion of Ntr1.

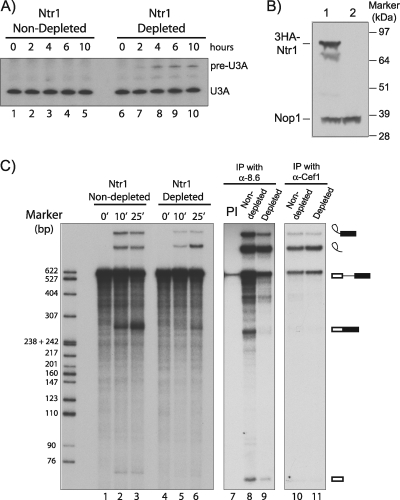

The NTR1 gene is essential for cell viability. Therefore, to investigate the requirement for Ntr1 protein for splicing, yeast strain KL4G, in which chromosomal NTR1 is transcribed under the control of the glucose-repressible PGAL1 promoter, was grown in galactose medium and then shifted to glucose medium. As a control, a second culture was treated identically but was transferred back to galactose medium. Approximately 2 h after the metabolic shift, the growth of the culture slowed considerably and then the cells continued to grow slowly (approximately 4-h doubling time; data not shown). Northern analysis of extracted RNA showed a barely detectable amount of unspliced pre-U3 RNA 2 h after the shift, with the amount increasing for 6 to 10 h postshift (Fig. 2A, lanes 6 to 10). Microarray analysis showed a mild splicing defect for some transcripts of intron-containing genes 2 h after the shift and a substantial genomewide accumulation of unspliced pre-mRNAs by 10 h postshift (data not shown). Extract from KL4G cells grown for 10 h in glucose contained a barely detectable amount of Ntr1 (Fig. 2B, lane 2) and, when incubated under in vitro splicing conditions with an ACT1 substrate RNA, produced only a small amount of spliced exons but accumulated a substantial amount of excised intron (Fig. 2C, lane 6) compared to nondepleted extract (Fig. 2C, lane 3). Incubation of the reaction mixtures with anti-Prp8 (lanes 8 and 9) or anti-Cef1 (lanes 10 and 11) antibodies showed that in Ntr1-depleted extract the excised intron is associated with both Prp8 and Cef1, supporting its accumulation in a postsplicing complex. When KL4G2T (same as KL4G but with TAP-tagged Ntr2) cells were treated similarly by growth in glucose for 10 h to deplete Ntr1, TAP-Ntr2 coprecipitated a substantial amount of excised intron from a splicing reaction mixture (Fig. 1B, lane 10). Therefore, Ntr2 is able to associate with the excised intron complex despite the substantial depletion of Ntr1. The difference in the amounts of the spliced exon and excised intron species in the Ntr1-depleted reaction mixture is most likely due to inhibition of splicing as a consequence of the retention of essential splicing factors within a postsplicing complex, in addition to which the excised intron RNA in the complex is protected against degradation (26). This indicates that Ntr1 is required for efficient pre-mRNA splicing and for metabolism of excised intron and suggests that Ntr1 might play a role in recycling the postspliceosome components for new rounds of splicing.

FIG. 2.

Effects of Ntr1 depletion on splicing in vitro. (A) Northern analysis of U3 snoRNA. BMA38 (lanes 1 to 5) or KL4G (PGAL1-3HA-NTR1; lanes 6 to 10) cells were grown in YPGR (galactose medium) to an OD600 of 0.5 and then transferred to YPD (glucose medium; repressing conditions). RNA was extracted after 0, 2, 4, 6, or 10 h following the shift, subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, blotted, and probed for U3A snoRNA. (B and C) KL4G cells were grown in YPGR to an OD600 of 0.5 and then transferred to YPD and grown for 10 h before harvesting to produce a splicing extract. A nondepleted control culture of KL4G was produced by similar treatment but with a return to YPGR instead of YPD. (B) Western blot assay showing the relative amounts of HA-tagged Ntr1 in KL4G cells at 0 h (lane 1) and at 10 h (lane 2) after the shift to YPD. Nop1 was probed as a loading control. (C) In vitro splicing assays with extracts derived from Ntr1-depleted (lanes 4 to 6) and nondepleted (lanes 1 to 3) cells. Aliquots (5 μl) were withdrawn and halted after incubation for 0, 10, and 25 min at 23°C. The RNAs were analyzed by fractionation in a 7% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel and autoradiography. Splicing reaction mixtures with Ntr1-depleted (lanes 9 and 11) and nondepleted (lanes 7, 8, and 10) extracts were incubated with preimmune (PI) serum (lane 7), anti-Prp8 antibodies (lane 8 and 9), or anti-Cef1 antibodies (lanes 10 and 11), and precipitated RNAs were extracted and analyzed as described above. The various RNA species are indicated diagrammatically on the right as described in the legend to Fig. 1. IP, immunoprecipitation.

The distribution of snRNPs in extracts from Ntr1-depleted and nondepleted cells was analyzed by fractionation in glycerol gradients, followed by Northern blotting. The densest fractions contained U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNPs and possibly some endogenous spliceosomes and/or postsplicing complexes (Fig. 3A and B, fractions 1 to 7) and then free U5 snRNPs (fractions 5 to 9), U4/U6 di-snRNPs (fractions 9 to 13), and free U6 snRNP (fractions 15 to 19). Quantification of these results showed that, compared with nondepleted extract, in Ntr1-depleted extract there was a 50% reduction in the amount of U4 snRNA in the high-density fractions (fractions 1 to 3) and a corresponding increase in the amount of U4 snRNA present in the form of U4/U6 di-snRNP (Fig. 3B, fractions 9 to 13), whereas the free U5 snRNP (fractions 5 to 9) was essentially absent in Ntr1-depleted extract. There was also a small but reproducible decrease in the level of free U6 snRNP (fractions 15 to 19), although this is less obvious, as free U6 snRNP is usually in excess. The dramatic shift of U4 snRNA from high-density fractions to the U4/U6 di-snRNP region of the gradient, combined with the reduction of free U5 and U6 snRNPs (and presumably of free U2 snRNP, although this cannot be assessed with these gradients), suggests a defect in recycling of snRNPs as a consequence of the defective disassembly of the postsplicing U2/U5/U6 snRNP complex. Thus, free U5 snRNP became the limiting factor for the conversion of U4/U6 di-snRNP to U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP (since U6 snRNP is in excess) and presumably tri-snRNP and/or free U2 snRNP became limiting for spliceosome assembly.

Next, the association of snRNAs with Prp8 in Ntr1-depleted and nondepleted extracts was examined by immunoprecipitation. As expected, anti-Prp8 antibodies efficiently pulled down U5, U4, and U6 snRNAs from nondepleted extract (Fig. 3C, lane 3) because of its presence in U5 snRNP and U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP (15). With Ntr1-depleted extract, immunoprecipitation of Prp8 pulled down an eightfold increased amount of U2 (compared to nondepleted extract and normalized against the total amounts in each extract) but only half the amount of U4 (Fig. 3C, lane 6) and an equivalent amount of U6. The increased association of Prp8 with a U2 snRNA-containing complex and decreased association with U4 snRNP in Ntr1-depleted extract supports the accumulation of Prp8 in the U2/U5/U6 excised intron-containing complex. These precipitates were also analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis to distinguish free U6 snRNA from a U4/U6 heterodimer that is derived from U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNPs following phenol extraction (nota bene, Prp8 is not a component of U4/U6 di-snRNPs or free U6 snRNPs). As shown in Fig. 3D, the Prp8 precipitate from Ntr1-depleted extract contained less U4/U6 heterodimer and more free U6 snRNA (presumably derived from the U2/U5/U6 complex) than the Prp8 precipitate from nondepleted extract. This supports the conclusion from the glycerol gradients that Ntr1 depletion results in a defect in recycling of snRNPs and indicates that Prp8 accumulates in a U2/U5/U6 snRNP complex.

Ntr1, Ntr2, and Prp43 cofractionate in at least two distinct complexes.

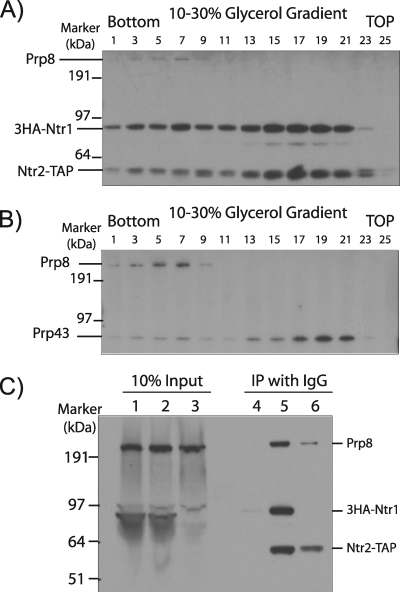

Ntr2, Prp8, and the excised intron release factor Prp43 are among many proteins that have been found in affinity-selected complexes along with Ntr1 (13, 16). To investigate this further, extract from KL4G2T cells containing HA-Ntr1 and Ntr2-TAP was fractionated in a glycerol gradient and alternate fractions were analyzed by precipitation of Ntr2-TAP with IgG-agarose and detection of precipitated proteins by Western blotting. Interestingly, HA-Ntr1 was associated with Ntr2-TAP in most of the gradient fractions (Fig. 4A, fractions 1 to 23), whereas Prp8 was associated with Ntr2-TAP only in the higher-density fractions (fractions 3 to 7) that contain high-molecular-weight complexes. Similarly, glycerol gradient fractionation of extract from KL4G cells (HA-tagged Ntr1 and nontagged Ntr2), followed by precipitation with anti-HA antibodies, showed coprecipitation of Prp8 and of Prp43 with HA-Ntr1 in the same high-density fractions (3 to 7) (Fig. 4B). Therefore, as Ntr2 pulls down Ntr1 and Prp8 and Ntr1 pulls down Prp8 and Prp43 in the same high-density fractions, it is most likely that these four proteins are present in the same high-molecular-weight complex. In addition, it is notable that the bulk of Ntr1-associated Ntr2 and Prp43 occurs in lower-density fractions (Fig. 4A and B, fractions 13 to 21). This likely represents an Ntr1/Ntr2/Prp43 complex that is not snRNP associated. Also, Ntr2-TAP coprecipitated both HA-Ntr1 and Prp8 in extract from galactose-grown (nondepleted) KL4G2T (PGAL-HA-Ntr1 and Ntr2-TAP) cells and coprecipitated Prp8 in extract from glucose-grown KL4G2T cells, despite the depletion of Ntr1 (Fig. 4C, lanes 5 and 6). Thus, although the level of Prp8 that coprecipitated with Ntr2 was lower in Ntr1-depleted extract, the association of Ntr2 and Prp8, whether direct or indirect, is not absolutely Ntr1 dependent, as is the case for its association with excised intron (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 4.

Associations among Ntr1, Ntr2, Prp43, and Prp8. (A and B) Glycerol gradient fractionation (without added ATP or pre-mRNA). (A) Extract from galactose-grown KL4G2T cells containing HA-Ntr1 and Ntr2-TAP was fractionated in a 10 to 30% glycerol gradient. Alternate gradient fractions were immunoprecipitated with IgG-agarose, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA and anti-Prp8 (8.6) antibodies. (B) KL4G cell extract containing HA-Ntr1 was fractionated in a 10 to 30% glycerol gradient. Alternate gradient fractions were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA agarose, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with affinity-purified anti-Prp43 antibodies and with anti-Prp8 antibodies. (C) Extracts (without added ATP or pre-mRNA) from galactose-grown (lanes 2 and 5) or glucose-grown (lanes 3 and 6) KL4G2T cells or from BMA38a (untagged control) cells (lanes 1 and 4) were incubated with IgG-agarose to precipitate Ntr2-TAP, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA and anti-Prp8 antibodies. Note that the Ntr2-TAP protein in whole extract is very poorly recognized by IgG on the blot. IP, immunoprecipitation.

Ntr1 is required for the association of Prp43 with the excised intron complex.

The interaction of Prp43 with the excised intron is only weakly detectable in an in vitro splicing reaction mixture, presumably because it is highly transient (38; our unpublished data). Martin et al. (26) have produced an ATPase-defective mutation (T123A) in conserved motif I of the Prp43 RNA helicase that confers a dominant negative phenotype such that the Prp43T123A protein interferes in trans with the in vitro splicing function of the wild-type Prp43 protein, blocking release of the excised intron from the spliceosome (26). Thus, the accumulation of postsplicing intron-retaining complex in the presence of the Prp43T123A protein provides a sensitive assay for the interaction of the Prp43T123A protein with this complex. We therefore tested whether the purified, recombinant Prp43T123A protein is able to associate with the postsplicing complex produced in reaction mixtures with Ntr1-depleted and nondepleted extracts. As shown in Fig. 5, the Prp43T123A protein coprecipitated excised intron RNA only from the reaction mixture with nondepleted extract (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 5). As a control, HA-tagged Ntr1 was affinity selected from galactose-grown KL4G cell extract that contained a very high concentration of HA-Ntr1. The affinity-selected material was unable, by itself, to support pre-mRNA splicing (data not shown); however, this protein partially restored the splicing activity of Ntr1-depleted extract (Fig. 5, lane 3) and allowed the Prp43T123A protein to coprecipitate the excised intron (Fig. 5, lane 6). These results show that the presence of Ntr1 is required for the interaction of Prp43 with the postsplicing excised intron complex and explains the observed accumulation of the excised intron complex in reaction mixtures with the Ntr1-depleted extract.

FIG. 5.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) of splicing reaction mixtures shows that Ntr1 is required for association of Prp43 with the excised intron. Ntr1-depleted (lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6) and nondepleted (lanes 1 and 4) extracts were prepared from KL4G cells grown as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Splicing reaction mixtures (50 μl) were assembled with 32P-labeled ACT1 substrate RNA and 0.9 μg of purified recombinant Prp43T123A. For reconstitution of the Ntr1-depleted extract (lanes 3 and 6), the splicing reaction mixture was mixed with 3HA-Ntr1 affinity selected from galactose-grown KL4G cell extract (overproducing 3HA-Ntr1). Following incubation for 25 min at room temperature, 90% of each splicing reaction mixture was mixed with 20 μl of affinity-purified anti-Prp43 antibodies immobilized on Sepharose CL45 beads in IPP150. After mixing at 4°C for 1 h, the beads were washed and the RNA was extracted. Precipitated RNA (lanes 4 to 6) and RNA extracted from 10% aliquots of the total reaction mixtures (lanes 1 to 3) were separated on a 7% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel. For each reconstitution reaction mixture, 10 μl of extract from YPGR-grown KL4G cells was incubated with anti-HA-agarose beads for 1 h at 4°C and the beads were washed five times with IPP150 buffer and once in 0.6 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) and then incubated with 0.5 μg of HA peptide (Sigma) for 8 h at 4°C to elute the HA-Ntr1 from the beads. Recombinant His10-tagged Prp43T123A protein was produced in Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)RIL (Stratagene) and purified essentially as described by Martin et al. (26). The various RNA species are indicated diagrammatically on the right as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

DISCUSSION

Evidence that the Ntr1 and Ntr2 proteins are components of the postsplicing excised intron complex includes the coprecipitation by Ntr1 and Ntr2 of the U2, U5, and U6 snRNPs (Fig. 1A); the coprecipitation of more excised intron than other intermediates or products of the pre-mRNA splicing process (Fig. 1B); and the association of Ntr2 with Ntr1 and Prp8 and of Ntr1 with Prp8 and with the intron release factor Prp43 in a high-molecular-weight complex (Fig. 4). Evidence that Ntr1 affects the release of excised intron RNA and dissociation of the postsplicing complex includes the reduced splicing activity and accumulation of excised intron in an in vitro splicing reaction mixture with Ntr1-depleted extract (Fig. 2C); the coprecipitation of the accumulated excised intron with Prp8 and Cef1 (Fig. 2C); the reorganization of snRNPs, including a reduction in U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNPs, and free U5 and U6 snRNPs, and accumulation of U4/U6 di-snRNPs, suggesting that snRNP regeneration after splicing is defective in an Ntr1-depleted splicing reaction mixture (Fig. 3B); the association of the U5 snRNP protein Prp8 with a U2/U5/U6 complex in an Ntr1-depleted splicing reaction mixture (Fig. 3C and D); and the failure of the Prp43T123A protein to associate with the excised intron in the absence of Ntr1 (Fig. 5). Furthermore, Northern and microarray analyses of pre-mRNA splicing demonstrate that Ntr1 is required for efficient splicing in vivo, as well as in vitro (Fig. 2A and data not shown).

Taken together, these data provide compelling evidence that Ntr1 and Ntr2 are present in the late-stage excised intron-containing spliceosome complex and that Ntr1 is required for the interaction of Prp43 with the excised intron prior to its release and recycling of the splicing factors. While the manuscript was under review, Tsai et al. (38) published data showing that metabolic depletion of Ntr2 resulted in accumulation of pre-mRNA and excised lariat-intron in vivo and that a dimeric complex of Ntr1 and Ntr2 is required for dissociation of spliceosomes and release of lariat-intron in vitro. The data presented here complement and extend that study, showing that Ntr1 is required both in vivo and in vitro for efficient splicing and for Prp43 to function in release of the excised intron and recycling of snRNPs. Tsai et al. (38) found that immunodepletion of Ntr1 quantitatively removed Ntr2 from cell extract and vice versa, indicating that these two proteins form a stable complex. We have shown that, following metabolic depletion of Ntr1, Ntr2 is still present in a complex with Prp8 (Fig. 4C) and with excised intron (Fig. 1B), indicating that Ntr2 can associate with late splicing complexes independently of Ntr1 but is not by itself sufficient to activate the intron release function of Prp43.

Ntr1 was originally named Spp382 after the role of this protein in suppression of the prp38-1 temperature-sensitive growth defect. Prp38 is a tri-snRNP-specific protein that was shown to be dispensable for spliceosome assembly but required for spliceosome maturation (6, 45). The depletion of Prp38 caused a spliceosome maturation defect with accumulation of U4/U6, and the temperature-sensitive prp38-1 mutant strain accumulated unspliced pre-mRNA at the nonpermissive temperature (45). The suppression of prp38-1 by Spp382/Ntr1 may suggest an additional role for this protein at an earlier stage, during spliceosome maturation. Alternatively, ntr1 mutations may alleviate the prp38-1 defect indirectly, for example, by moderating the interaction of Ntr1 with a common interacting factor or altering the rate of spliceosome assembly by affecting the availability of splicing factors.

Near its N terminus, Ntr1 contains a G-patch region (glycine-rich sequence found in nucleic binding proteins [2], amino acids 61 to 106) that is the most highly conserved region of this protein. The mammalian G-patch protein called TFIP11 (tuftelin-interacting protein) is a possible ortholog of Ntr1. Human TFIP11 has been found in affinity-purified spliceosomes (18, 46), and mouse TFIP11 was reported to affect the alternative splicing of an adenovirus E1A reporter transcript in a transfection assay (44).

Interestingly, yeast Spp2, another G-patch protein and spliceosome component, interacts with the ATP-dependent DExH-box splicing factor Prp2 (33). As this interaction involves the G-patch sequence in Spp2 and is required for the recruitment of Prp2 to the spliceosome prior to the first catalytic step of splicing, it was proposed that Spp2 may be an accessory factor that confers spliceosome specificity on Prp2 (33). Thus, Ntr1 appears to be an analogous accessory factor for Prp43, targeting it to the excised intron complex, in addition to which it might conceivably be a cofactor for Prp43 helicase activity. Tsai et al. (38) showed that the G-patch region of Ntr1 interacted with Prp43 in a two-hybrid assay. Thus, Ntr1 might promote the interaction of Prp43 with the excised intron through an RNA binding activity of the G-patch region. The role of Ntr2 in these proposed functions remains to be determined.

Intriguingly, Prp43 was recently shown to function also in ribosome synthesis and to associate both with ribosome precursor complexes and with mature ribosomes (12, 20, 21). It is not known how Prp43 is targeted to these distinct cellular processes or whether this dual function allows Prp43 to coordinate the regulation of ribosome biogenesis with pre-mRNA splicing, a process that is vital for ribosomal protein synthesis in budding yeast as many ribosomal protein genes contain an intron. It will be interesting to determine whether Ntr1 acts as an accessory factor for both of these processes or interacts with only a fraction of Prp43, conferring splicing specificity and possibly regulating this in response to different metabolic requirements of the cell.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Y. Henry for the generous gift of affinity-purified anti-Prp43 antibodies, to K. Gould for Cef1 antibodies, to J. Aris for anti-Nop1 antibodies, and to B. Schwer for the His-PRP43T123A expression plasmid. Thanks to Martin Reijns for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was funded by studentships from The Darwin Trust of Edinburgh to K.L.B. and T.A. and by Wellcome Trust grant 067311 to J.D.B. G.E.-G. is supported by NIH grant R15 GM072622. C.D. was supported by an EMBO fellowship. J.D.B. is a Royal Society Darwin Trust Professor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers, M., A. Diment, M. Muraru, C. S. Russell, and J. D. Beggs. 2003. Identification and characterization of Prp45p and Prp46p, essential pre-mRNA splicing factors. RNA 9:138-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and E. V. Koonin. 1999. G-patch: a new conserved domain in eukaryotic RNA-processing proteins and type D retroviral polyproteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:342-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arenas, J. E., and J. N. Abelson. 1997. Prp43: an RNA helicase-like factor involved in spliceosome disassembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:11798-11802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartels, C., H. Urlaub, R. Luhrmann, and P. Fabrizio. 2003. Mutagenesis suggests several roles of Snu114p in pre-mRNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 278:28324-28334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baudin-Baillieu, A., E. Guillemet, C. Cullin, and F. Lacroute. 1997. Construction of a yeast strain deleted for the TRP1 promoter and coding region that enhances the efficiency of the polymerase chain reaction-disruption method. Yeast 13:353-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanton, S., A. Srinivasan, and B. C. Rymond. 1992. PRP38 encodes a yeast protein required for pre-messenger RNA splicing and maintenance of stable U6 small nuclear RNA levels. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:3939-3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon, K.-L., C. Norman, R. J. Grainger, A. Newman, and J. D. Beggs. 2006. Prp8p dissection reveals domain structure and protein interaction sites. RNA 12(2):198-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brow, D. A. 2002. Allosteric cascade of spliceosome activation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36:333-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burge, C. B., T. Tuschl, and P. A. Sharp. 1999. Splicing of precursors to mRNAs by the spliceosome, p. 525-560. In R. F. Gesteland, T. R. Cech, and J. F. Atkins (ed.), The RNA world, edition 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 10.Chan, S. P., D. I. Kao, W. Y. Tsai, and S. C. Cheng. 2003. The Prp19p-associated complex in spliceosome activation. Science 302:279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan, S. P., and S. C. Cheng. 2005. The Prp19-associated complex is required for specifying interactions of U5 and U6 with Pre-mRNA during spliceosome activation. J. Biol. Chem. 280:31190-31199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Combs, D. J., R. J. Nagel, M. Ares, Jr., and S. W. Stevens. 2006. Prp43p is a DEAH-box spliceosome disassembly factor essential for ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:523-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gavin, A. C., M. Bosche, R. Krause, P. Grandi, M. Marzioch, A. Bauer, J. Schultz, J. M. Rick, A. M. Michon, C. M. Cruciat, et al. 2002. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gietz, D., A. St. Jean, R. Woods, and R. Schiestl. 1992. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grainger, R. J., and J. D. Beggs. 2005. Prp8 protein: at the heart of the spliceosome. RNA 11:533-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazbun, T. R., L. Malmström, S. Anderson, B. Graczyk, B. Fox, M. Riffle, B. Sundin, J. Aranda, W. McDonald, and C. Chiu. 2003. Assigning function to yeast proteins by integration of technologies. Mol. Cell 12:1353-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito, T., T. Chiba, R. Ozawa, M. Yoshida, M. Hattori, and Y. Sakaki. 2001. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4569-4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jurica, M. S., and M. J. Moore. 2003. Pre-mRNA splicing: awash in a sea of proteins. Mol. Cell 12:5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konarska, M. M., and P. A. Sharp. 1987. Interactions between small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles in formation of spliceosomes. Cell 49:763-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lebaron, S., C. Froment, M. Fromont-Racine, J. C. Rain, B. Monsarrat, M. Caizergues-Ferrer, and Y. Henry. 2005. The splicing ATPase Prp43p is a component of multiple preribosomal particles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:9269-9282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leeds, N. B., E. C. Small, S. L. Hiley, T. R. Hughes, and J. P. Staley. 2006. The splicing factor Prp43p, a DEAH box ATPase, functions in ribosome biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:513-522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin, R.-J., A. J. Newman, S.-C. Cheng, and J. Abelson. 1985. Yeast mRNA splicing in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 260:14780-14792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, D. J. DeMarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makarov, E. M., O. V. Makarova, H. Urlaub, M. Gentzel, C. L. Will, M. Wilm, and R. Luhrmann. 2002. Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein remodeling during catalytic activation of the spliceosome. Science 298:2205-2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makarova, O. V., E. M. Makarov, H. Urlaub, C. L. Will, M. Gentzel, M. Wilm, and R. Luhrmann. 2004. A subset of human 35S U5 proteins, including Prp19, function prior to catalytic step 1 of splicing. EMBO J. 23:2381-2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin, A., S. Schneider, and B. Schwer. 2002. Prp43 is an essential RNA-dependent ATPase required for release of lariat-intron from the spliceosome. J. Biol. Chem. 277:17743-17750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohi, M. D., and K. L. Gould. 2002. Characterization of interactions among the Cef1p-Prp19p-associated splicing complex. RNA 8:798-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohi, M. D., A. J. Link, J. L. Jennings, W. H. McDonald, L. Ren, and K. L. Gould. 2002. Proteomics analysis reveals stable multi-protein complexes in both fission and budding yeasts containing Myb-related Cdc5p/Cef1p, novel pre-mRNA splicing factors, and snRNAs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2011-2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Keefe, R. T., C. Norman, and A. J. Newman. 1996. The invariant U5 snRNA loop 1 sequence is dispensable for the first catalytic step of pre-mRNA splicing in yeast. Cell 86:679-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puig, O., A. Gottschalk, P. Fabrizio, and B. Seraphin. 1999. Interaction of the U1 snRNP with nonconserved intronic sequences affects 5′ splice site selection. Genes Dev. 13:569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raghunathan, P. L., and C. Guthrie. 1998. A spliceosomal recycling factor that reanneals U4 and U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles. Science 279:857-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwer, B., and C. H. Gross. 1998. Prp22, a DExH box RNA helicase, plays two distinct roles in yeast pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 17:2085-2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman, E. J., A. Maeda, J. Wei, P. Smith, J. D. Beggs, and R. J. Lin. 2004. Interaction between a G-patch protein and a spliceosomal DEXD/H-box ATPase that is critical for splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:10101-10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Staley, J. P., and C. Guthrie. 1998. Mechanical devices of the spliceosome: motors, clocks, springs, and things. Cell 92:315-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tarn, W. Y., C. H. Hsu, K. T. Huang, H. R. Chen, H. Y. Kao, K. R. Lee, and S. C. Cheng. 1994. Functional association of essential splicing factor(s) with PRP19 in a protein complex. EMBO J. 13:2421-2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tarn, W. Y., K. R. Lee, and S. C. Cheng. 1993. Yeast precursor messenger RNA processing protein PRP19 associates with the spliceosome concomitant with or just after dissociation of U4 small nuclear RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:10821-10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teigelkamp, S., A. J. Newman, and J. D. Beggs. 1995. Extensive interactions of PRP8 protein with the 5′ and 3′ splice sites during splicing suggest a role in stabilization of exon alignment by U5 snRNA. EMBO J. 14:2602-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai, R. T., R. H. Fu, F. L. Yeh, C. K. Tseng, Y. C. Lin, Y. h. Huang, and S. C. Cheng. 2005. Spliceosome disassembly catalyzed by Prp43 and its associated components Ntr1 and Ntr2. Genes Dev. 19:2991-3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uetz, P., L. Giot, G. Cagney, T. A. Mansfield, R. S. Judson, J. R. Knight, D. Lockshon, V. Narayan, M. Srinivasan, P. Pochart, A. Qureshi-Emili, Y. Li, B. Godwin, D. Conover, T. Kalbfleisch, G. Vijayadamodar, M. Yang, M. Johnston, S. Fields, and J. M. Rothberg. 2000. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403:623-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umen, J. G., and C. Guthrie. 1995. A novel role for a U5 snRNP protein in 3′ splice site selection. Genes Dev. 9:855-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verdone, L., S. Galardi, D. Page, and J. D. Beggs. 2004. Lsm proteins promote regeneration of pre-mRNA splicing activity. Curr. Biol. 14:1487-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villa, T., and C. Guthrie. 2005. The Isy1p component of the NineTeen complex interacts with the ATPase Prp16p to regulate the fidelity of pre-mRNA splicing. Genes Dev. 19:1894-1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wagner, J. D., E. Jankowsky, M. Company, A. M. Pyle, and J. N. Abelson. 1998. The DEAH-box protein PRP22 is an ATPase that mediates ATP-dependent mRNA release from the spliceosomes and unwinds RNA duplexes. EMBO J. 17:2926-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wen, X., Y. P. Lei, Y. L. Zhou, C. T. Okamoto, M. L. Snead, and M. L. Paine. 2005. Structural organization and cellular localization of tuftelin-interacting protein 11 (TFIP11). Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:1038-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie, J., K. Beickman, E. Otte, and B. C. Rymond. 1998. Progression through the spliceosome cycle requires Prp38p function for U4/U6 snRNA dissociation. EMBO J. 17:2938-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou, Z., L. J. Licklider, S. P. Gygi, and R. Reed. 2002. Comprehensive proteomic analysis of the human spliceosome. Nature 419:182-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]