Abstract

The tyrosine kinase Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) transduces signaling for the majority of known cytokine receptor family members and is constitutively activated in some cancers. Here we examine the mechanisms by which the adapter proteins SH2-Bβ and APS regulate the activity of JAK2. We show that like SH2-Bβ, APS binds JAK2 at multiple sites and that binding to phosphotyrosine 813 is essential for APS to increase active JAK2 and to be phosphorylated by JAK2. Binding of APS to a phosphotyrosine 813-independent site inhibits JAK2. Both APS and SH2-Bβ increase JAK2 activity independent of their N-terminal dimerization domains. SH2-Bβ-induced increases in JAK2 dimerization require only the SH2 domain and only one SH2-Bβ to be bound to a JAK2 dimer. JAK2 mutations and truncations revealed that amino acids 809 to 811 in JAK2 are a critical component of a larger regulatory region within JAK2, most likely including amino acids within the JAK homology 1 (JH1) and JH2 domains and possibly the FERM domain. Together, our data suggest that SH2-Bβ and APS do not activate JAK2 as a consequence of their own dimerization, recruitment of an activator of JAK2, or direct competition with a JAK2 inhibitor for binding to JAK2. Rather, they most likely induce or stabilize an active conformation of JAK2.

Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) is a widely expressed member of the Janus family of tyrosine kinases and participates in the signaling of two-thirds of the known cytokine receptors, including the receptors for gamma interferon, leptin, growth hormone (GH), erythropoietin, and interleukin-12 (17, 30). JAK2's importance is further underscored by its susceptibility to mutational activation leading to cell transformation. One such mutation includes the [t(9;12)(p24;p13)] chromosomal translocation, which creates a fusion of the dimerization domain of the transcription factor, Tel, and the kinase domain of JAK2, identified for certain patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (16, 31). A recently discovered point mutation in JAK2, in which valine 617 is mutated to phenylalanine, results in the human clonal myeloproliferative disorder polycythemia vera (14, 18, 52). Thus, further study of how JAK2 is regulated is important not only for understanding the signaling of a majority of cytokine receptors but also for elucidating the mechanisms by which JAK2 can transform cells.

The JAK family of receptor-associated tyrosine kinases mediates growth and differentiation in response to ligand binding to type I and II cytokine receptors, including receptors for interferons, most interleukins, and GH. Binding of ligand to a cytokine receptor is thought to lead to conformational changes within the receptor that result in dimerization of the receptor-associated JAKs (1, 48). Dimerization of the JAKs allows for auto- and/or transphosphorylation of tyrosine residues within the kinase's activation loop, causing a conformational change that fully activates the JAKs (17). JAK activation leads to the autophosphorylation of multiple tyrosines as well as the phosphorylation of the associated receptor. Phosphorylated tyrosines in JAKs and their associated cytokine receptors provide binding sites for recruitment of downstream signaling molecules, which bind via phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) (45) and Src homology 2 (SH2) domains. Such downstream signaling molecules include the family of transcription factors known as signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs), which provide a rapid means of linking signals at the membrane to transcription within the nucleus (3).

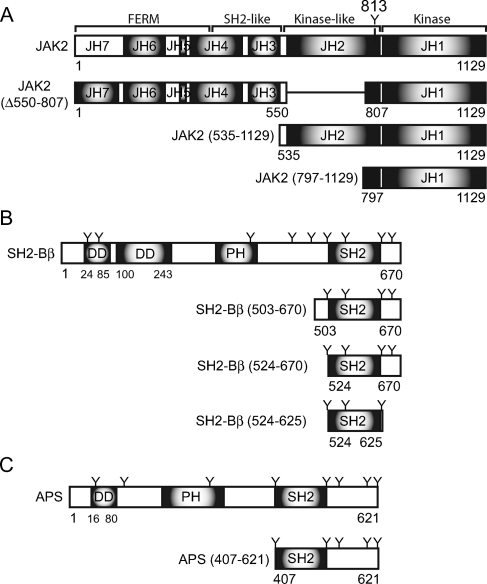

Members of the JAK family possess seven JAK homology (JH) domains (Fig. 1A) (48), the functions of which are only beginning to be understood. JH1 is the C-terminal kinase domain (6, 54). JH2 is a catalytically inactive kinase-like domain (47). JH3 and part of JH4 form an SH2-like domain which appears to possess no phosphotyrosine-binding ability (9). Finally, the N terminus of the JAK (part of JH4 and JH domains 5 to 7) contains a FERM (band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, and moesin) domain that is required for cytokine receptor binding (53). Intriguingly, JAK2 exhibits a certain degree of internal self-regulation. Deletion of the pseudokinase domain of JAK2, JH2, has been shown to increase substantially JAK2 activity (7, 39, 40). Three inhibitory regions that mediate a negative interaction between the pseudokinase domain and the kinase domain have been identified within JH2 (41). The activating JAK2 mutation V617F, which causes myeloproliferative disorders, also lies within the JH2 domain. Thus, interaction between the JH1 and JH2 domains of JAK2 appears to play a central role in the regulation of JAK2 activity.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of JAK2, SH2-Bβ, and APS. (A) JAK2 is composed of seven JH domains. JAK2 (Δ550-807), JAK2 (535-1129), and JAK2 (797-1129) represent JAK2 mutants used in Fig. 10. (B) SH2-B is composed of an SH2 domain, a PH domain, and two identified dimerization domains (DD), as well as nine tyrosines (Y). SH2-Bβ (524-670) is used in Fig. 6, SH2-Bβ (524-625) is used in Fig. 6 and 7, and SH2-Bβ (503-670) is used in Fig. 7. (C) APS is composed of an SH2 domain, a PH domain, eight tyrosines (Y), and at least one identified dimerization domain. APS (407-621) is used in Fig. 5.

Positive regulation of JAK2 activity has also been observed. Active JAK2 binds and phosphorylates SH2-B (37), a protein that has been shown to potently enhance JAK2 activity (35). SH2-B is a member of a family of proteins that also includes APS and LNK (11, 29, 50). The domain structure of these proteins consists of a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain and an SH2 domain, as well as multiple prolyl-rich regions, suggesting they function as adaptor proteins (Fig. 1B and C). Additionally, both SH2-B and APS have been reported to possess one or two N-terminal dimerization domains (4, 25, 32). There are four known isoforms (α, β, γ, and δ) of SH2-B, which differ only in their C termini downstream of the SH2 domain (24, 29, 37, 51).

Although all three SH2-B family members possess similar domain structures, their roles in cell signaling do not necessarily overlap. Indeed, while overexpression of SH2-Bβ consistently stimulates the activity of overexpressed, constitutively active JAK2, APS has been reported to have a modest or no stimulatory effect on JAK2 activity (25, 27, 35). Consistent with results with overexpressed JAK2, SH2-Bβ has been shown to substantially enhance GH-induced tyrosyl phosphorylation of endogenous JAK2 and the downstream (overexpressed) effector protein STAT5b in COS7 cells and 293T cells (25, 27, 35) and of endogenous JAK2 in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts (25, 35). In contrast, APS was reported to stimulate GH-induced tyrosyl phosphorylation of both endogenous JAK2 and endogenous STAT5b in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts (25, 35) but actually inhibit GH-stimulated endogenous JAK2 and overexpressed STAT5b in 293T cells (27). LNK was recently reported to inhibit erythropoietin stimulation of JAK2 (44).

A number of physiologic roles for APS and SH2-B have been examined using knockout mice. APS knockout mice exhibit an increase in B-1 cell number and an enhanced humoral immune response against a thymus-independent type 2 antigen. They have been reported either to have increased insulin sensitivity and hypoinsulinemia (22) or to exhibit no difference from their wild-type littermates in these parameters (19). SH2-B knockout mice exhibit age-dependent hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and glucose intolerance (5), as well as small, anovulatory ovaries and small testes with decreased sperm production (28), indicating a role for SH2-B in maintaining both carbohydrate homeostasis and fertility. Studies with SH2-B knockout mice further revealed SH2-B to be a key regulator of leptin sensitivity, energy balance, and body weight (34). Dissecting the mechanisms by which SH2-B and APS function, therefore, could provide substantial therapeutic benefit.

The precise mechanism by which SH2-Bβ and APS regulate JAK2 is only poorly understood. SH2-Bβ has been shown to have two binding sites for JAK2. The first involves the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ and a phosphorylated tyrosine (presumably phosphotyrosine 813) in JAK2 (15). The second involves the PH domain and amino acids 410 to 555 of (rat) SH2-Bβ and does not require JAK2 to be active and phosphorylated on tyrosines (36). Binding of SH2-Bβ to JAK2 through the first binding site is thought to be required for SH2-Bβ to enhance the activity of JAK2 (15, 37). Binding of APS's SH2 domain to a phosphorylated tyrosine in JAK2 is also thought to be required for APS to activate JAK2 (4). Dimerization of SH2-Bβ and APS via an N-terminal dimerization domain (amino acids 24 to 85 of human SH2-B and amino acids 24 to 85 of human APS) (schematic in Fig. 1B and C) has been proposed to increase JAK2 activity through formation of [JAK2]2[SH2-B]2 or [JAK2]2[APS]2 heterotetramers, which bring the two JAK2 molecules into close enough proximity to facilitate transphosphorylation and activation of JAK2 (25). A different dimerization domain located between amino acids 100 and 243 of (rat) SH2-Bβ was similarly hypothesized by Qian and Ginty (32) to be required for SH2-B to augment TrkA-mediated nerve growth factor signaling (32). A comparable domain is present in APS. A third dimerization domain critical for APS activation of insulin receptor within APS's SH2 domain was identified from the crystal structure of the SH2 domain of APS complexed with the catalytic domain of the insulin receptor (10). A corresponding domain is not thought to exist in SH2-B.

In this work, we investigated further the mechanism by which APS and SH2-Bβ interact with and regulate JAK2 activity. We show that both SH2-Bβ and APS bind directly to phosphorylated tyrosine 813 in JAK2 but not to unphosphorylated tyrosine 813 and that binding of APS to phosphotyrosine 813, like that of SH2-Bβ, is required for APS to increase active JAK2 and be a substrate of JAK2. We also provide evidence for a previously unrecognized second, inhibitory, binding site between APS and JAK2. Activation of JAK2 by SH2-Bβ requires only the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ and only one SH2 domain to be bound to a JAK2 dimer. Neither of the N-terminal dimerization domains of SH2-Bβ or APS is required for the activation of JAK2. Only the kinase (JH1) domain plus phosphotyrosine 813 of JAK2 is required for JAK2 activation by SH2-Bβ, although other domains of JAK2 are required for maximal SH2-Bβ-induced enhancement of JAK2 activity. Mutation of amino acids 809 to 811 of JAK2 increases the amount of active JAK2, suggesting that regions proximal to tyrosine 813 may form a negative regulatory region. These and other data provide strong evidence that dimerization of SH2-Bβ is not required for SH2-Bβ to activate JAK2. Rather, they favor SH2-Bβ (and presumably APS) stimulating the activity of JAK2 by inducing a conformational change within JAK2 or stabilizing an already active conformation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The QuikChange mutagenesis kit used was from Stratagene. COS7 cells were from the American Type Culture Collection. Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium was from Cambrex. Fetal bovine serum, the antibiotic-antimycotic solution, trypsin-EDTA, and Magic Mark XP Western standards were from Invitrogen. Aprotinin, leupeptin, and Triton X-100 were from Roche. 2-Mercaptoethanol, cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B (product code, C-9142), anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (product code, A1025), and anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (product code, F3165; used for immunoblotting at a dilution of 1:1,000) were from Sigma. Antibody recognizing and specific to a peptide containing phosphorylated tyrosines 1007 and 1008 of JAK2 (αpY1007/1008) was kindly provided by M. Myers (University of Michigan) and was used for immunoblotting at a dilution of 1:2,000. The anti-hemagglutinin 11 (HA.11) monoclonal antibody (αHA) (catalog number, MMS-101R) was from Berkley Antibody Company and was used for immunoblotting at a dilution of 1:2,000. Monoclonal antibody against myc tag (αmyc; 9E10) was from Santa Cruz and was used for immunoprecipitation at a dilution of 1:100 and for immunoblotting at a dilution of 1:10,000. Antibodies to JAK2 (αJAK2) and phosphotyrosine 4G10 (αPY) from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., were used for immunoblotting at dilutions of 1:10,000 and 1:7,500, respectively. As shown below (see Fig. 3A), a mouse monoclonal antibody to JAK2 (αJAK2) from Biosource was used for immunoblotting at a concentration of 1:20,000. IRDye 800-conjugated affinity-purified anti-green fluorescent protein (αGFP), anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), and anti-rabbit IgG were from Rockland. Recombinant protein A-agarose was from Repligen. Hybond-C Extra nitrocellulose was from Amersham Biosciences. Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG were from Molecular Probes. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Invitrogen. Peptides composed of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated tyrosine 813 (SLFTPDpYELLTEND and SLFTPDYELLTEND, respectively), and phosphorylated and unphosphorylated tyrosine 1007 (PQDKEpYYKVKEPGES and PQDKEYYKVKEPGES, respectively) (lowercase p indicates the site of phosphorylation) were synthesized at the University of Michigan Protein Structure Facility.

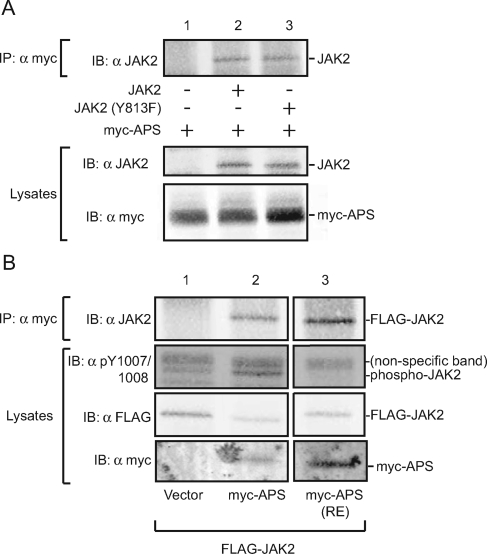

FIG. 3.

APS binds phosphotyrosine 813 and other regions of JAK2. (A) COS7 cells were transfected with 2.0 μg cDNA for APS along with 1.0 μg of empty vector (lane 1) or with cDNA encoding FLAG-JAK2 (lane 2) or FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) (lane 3). Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with αmyc and immunoblotted with αJAK2 (top panel). Cell lysates were immunoblotted with αJAK2 (middle panel) or αmyc (bottom panel). (B) cDNA (1.0 μg) encoding FLAG-JAK2 was coexpressed in COS7 cells with 2.0 μg of empty vector (lane 1) or with cDNA encoding myc-APS (lane 2) or myc-APS (R437E) (lane 3). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with αmyc, and immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with αJAK2 (top panel). Cell lysates were immunoblotted with αpY1007/1008 (second panel), αFLAG (third panel), and αmyc (bottom panel). All three lanes were obtained from the same gel. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

Plasmids.

The prk5 mammalian expression vector encoding wild-type murine JAK2 (gi 309463) was a generous gift from J. Ihle (St. Jude Children's Hospital, Memphis, TN) (42) and was used to create a JAK2 mutant containing a tyrosine-to-phenylalanine substitution at position 813 as described previously (15). The nucleotide sequence GACTACAAGGACGACGATGACAAG, which encodes the FLAG epitope, was inserted 5′ to both the wild-type and Y813F mutant JAK2 sequences using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit to generate a FLAG tag immediately N terminal to residue 4 (Ala) of JAK2 (FLAG-JAK2). The mutation GCCTGTTTACT to GCCTGaTTACT was used to produce JAK2 (F809I), GTTTACTCCA to GTTTtCTCCA for JAK2 (T810S), TTACTCCAGA to TTACTtCAGA for JAK2 (P811S), and CCTGTTTACTCCAGA to CCTGaTctCTtCAGA for JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS) (mutated base pairs are indicated in lowercase). The pCIneo mammalian expression vector (Promega), encoding C-terminally HA-tagged wild-type murine JAK2 (JAK2-HA) or JAK2 lacking amino acids 549 to 803 [JAK2 (Δ549-803)-HA], as well as the prk5 vector encoding C-terminally HA tagged amino acids 535 to 1129 of JAK2 [JAK2 (535-1129)-HA], was described previously (40). The PCMV-tag2B expression vector encoding N-terminally FLAG-tagged amino acids 797 to 1129 of murine JAK2 [FLAG-JAK2 (797-1129)] was described previously (15). The mammalian expression prk5 vector encoding wild-type human JAK3 (gi 309463) was a generous gift from J. O'Shea (NIH, Bethesda, MD) (38). The mutation CCTCATCTCTTCAGA to CCTCtTCaCTcCAGA was used to generate JAK3 (ISS781-783FTP). The prk5 vector encoding rat SH2-Bβ (gi 2920647) with a myc tag at the N terminus (35) (myc-SH2-Bβ) and the vector encoding myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) (36) have been described previously. Mutation of the base pairs of myc-SH2-Bβ from CCCCTCTCAGGC to CCCggaTCcGGC was used to generate a BamHI site at the codon preceding that coding for amino acid 524 in SH2-Bβ. Digestion with BamHI, followed by religation, yielded the construct myc-SH2-Bβ (524-670). Mutation of the base pairs of myc-SH2-Bβ (524-670) from GTGCCCTCCCAG to GTGtgaattCAG generated a stop codon and an EcoRI site at the codon following amino acid 625 in SH2-Bβ. Digestion with EcoRI followed by religation yielded the construct myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625). The cDNA encoding myc-tagged rat APS (gi 16758939) was kindly provided by D. D. Ginty (33). Mutation of the base pairs of myc-APS from ACTCTCCGACTA to ACTgTCgacCTA was used to generate a SalI site at the codon following amino acid 620 in APS. Digestion with SalI followed by religation yielded the construct myc-APS (407-620). The mammalian expression vector pEF-FLAG-I/m4A2 encoding murine suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS-1) was a generous gift from D. J. Hilton (The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research and The Cooperative Research Center for Cellular Growth Factors, Parkville, Victoria, Australia) (43).

Cell culture and transfection.

COS7 cells (in 100-mm dishes) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with antibiotic-antimycotic solution (100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 0.25 μg of amphotericin per ml) and 8% fetal bovine serum. They were transiently transfected using calcium phosphate precipitation (2). At 16 h after transfection, cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with culture medium. COS7 cells were harvested 48 h posttransfection.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

COS7 cells were washed three times in chilled PBSV (10 mM sodium phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na3VO4 [pH 7.4]) and solubilized in 800 μl lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4 [pH 7.5]) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin (10 μg/ml), and leupeptin (10 μg/ml). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 16,750 × g for 10 min. An aliquot (100 μl) of the supernatant was saved for Western blotting. The remaining supernatant (700 μl) was incubated either with concentrated αFLAG affinity gel (20 μl) on a rotator for 2 h at 4°C or with αmyc on ice for 2 h, and the immune complexes were subsequently collected on protein A-agarose beads (40 μl) during 1 h of incubation at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and boiled for 5 min in a mixture (80:20) of lysis buffer and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% SDS, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, 40% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue). One-half of the solubilized proteins in the immunoprecipitate and one-fourth of the proteins in the lysate aliquot were separated by SDS-PAGE (using either 10% or 4 to 20% gels). Proteins in the gel were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and detected by immunoblotting with the indicated antibody by use of an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Bio-sciences).

Coupling of peptides to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B and binding to proteins.

Cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B beads (0.057 g) were swelled for 15 min in 1 mM HCl and then washed 10 times with an additional 1 mM HCl. The beads were centrifuged at 600 rpm and washed with coupling buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3 [pH 8.3], 0.5 M NaCl) and immediately incubated overnight at 4°C with the peptide solution (0.855 μmol peptide dissolved in 400 μl coupling buffer). The beads were then centrifuged at 6,000 rpm, incubated with 400 μl 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.0), and rotated overnight at 4°C. The coupled beads were then washed sequentially with coupling buffer, 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4), coupling buffer, acetate buffer, and coupling buffer.

To test for binding of proteins with the coupled peptides, beads (20 μl) were incubated with cell lysates and rotated at 4°C for 2 h. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and boiled for 5 min in a mixture (80:20) of lysis buffer and SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were then analyzed as described in Results.

All experiments were performed at least twice with similar results; most were performed two or more times, with some being performed as many as six times. Results were quantified using the Odyssey software and included in the analysis only if the levels of the protein being studied (e.g., JAK2 when analyzing the phosphorylation of JAK2) were similar under all experimental conditions. Results were normalized to the level of protein being studied, as indicated in the figure legends. Results show the means ± standard errors of the mean or the range of values when the value for n was 2. Statistical significance was determined using a one-tailed paired Student t test. Results were considered significantly different if the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

APS and SH2-Bβ directly bind phosphotyrosine 813 of JAK2.

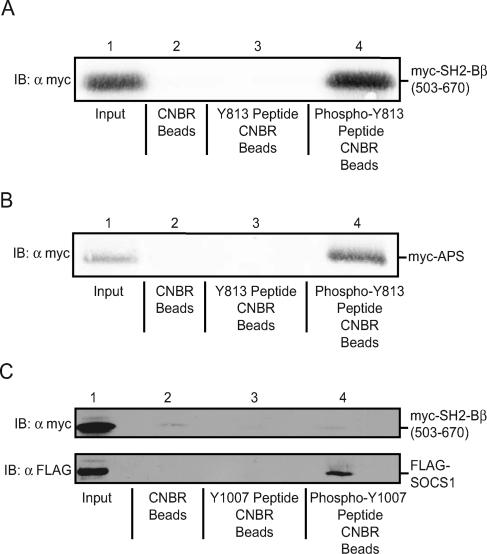

Previously we showed that mutation of tyrosine 813 of JAK2 to phenylalanine inhibits coprecipitation of activated JAK2 with SH2-Bβ as well as SH2-Bβ-mediated increased activation of JAK2 and STAT5b (15), suggesting that SH2-Bβ binds JAK2 at phosphorylated tyrosine 813. Because the SH2 domain of the SH2-B family member, APS, is 79% identical to the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ, we reasoned that APS most likely binds phosphotyrosine 813 of JAK2 as well. To determine whether APS binds to phosphorylated tyrosine 813 of JAK2, lysates of COS7 cells overexpressing myc-APS were incubated with uncoupled Sepharose 4B beads, with beads coupled to a peptide containing phosphotyrosine 813 (SLFTPDpY813ELLTEND), or with beads coupled to the equivalent peptide containing unphosphorylated Y813. Bound proteins were eluted and immunoblotted with αmyc. As a positive control, the same experiment was carried out with lysates from cells overexpressing the myc-tagged SH2 domain and the C terminus of SH2-Bβ, myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) (schematic in Fig. 1B). Figure 2A reveals that myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) binds to the phosphorylated Y813 peptide but not to the unphosphorylated Y813 peptide or the unconjugated beads, in accordance with SH2-Bβ binding JAK2 at phosphotyrosine 813. Similarly, Fig. 2B demonstrates that, like SH2-Bβ, myc-APS binds to the phosphorylated Y813 peptide but not to the unphosphorylated Y813 peptide or the unconjugated beads, implicating phosphotyrosine 813 as an APS-binding site on JAK2.

FIG. 2.

APS and SH2-Bβ bind phosphorylated tyrosine 813 of JAK2 but not unphosphorylated tyrosine 813. (A and B) Lysates of COS7 cells transfected with cDNA (5.0 μg) for myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) (A) or myc-APS (B) were incubated with unconjugated beads (lanes 2), beads coupled to the Y813 peptide (lanes 3), or beads coupled to the phospho-Y813 peptide (lanes 4). Proteins in cell lysates (lanes 1) and proteins that bound to the beads (lanes 2 to 4) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with αmyc. (C) Lysates of COS7 cells transfected with cDNA (5.0 μg) encoding either FLAG-SOCS-1 or myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) were incubated with unconjugated beads (lane 2), beads coupled to the Y1007 peptide (lane 3), or beads coupled to the phospho-Y1007 peptide (lane 4). Proteins in cell lysates (lane 1) and proteins that bound to the beads (lanes 2 to 4) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with αmyc (upper panel) or αFLAG (lower panel). IB, immunoblot.

To verify that SH2-Bβ does not bind phosphopeptides nonspecifically, we performed the same experiment using a peptide containing phosphotyrosine 1007. Western blotting with αmyc shows that overexpressed myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) does not bind to either the unphosphorylated or the phosphorylated Y1007 peptide (Fig. 2C, top panel). As a positive control for the phosphorylated Y1007 peptide, we showed that overexpressed FLAG-SOCS-1 bound the phosphorylated but not the unphosphorylated Y1007 peptide (Fig. 2C, bottom panel), as reported previously (49). These results show that the SH2 domains of SH2-Bβ and APS bind directly and specifically to the phosphorylated form of tyrosine 813.

APS binds JAK2 in a phosphotyrosine-independent manner.

To determine if phosphorylated tyrosine 813 is the sole binding site in JAK2 for APS, we coexpressed myc-APS with FLAG-JAK2 or FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) in COS7 cells, lysed the cells, and immunoprecipitated myc-APS and associated proteins from cell lysates using αmyc. Immunoblotting with αJAK2 shows that both FLAG-JAK2 and FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) coprecipitate with myc-APS (Fig. 3A, top panel), indicating that APS binds JAK2 at a site(s) in addition to tyrosine 813. No αJAK2 band was detected in the absence of JAK2 coexpression. Immunoblotting cell lysates with αJAK2 (Fig. 3A, middle panel) revealed similar levels of overexpressed JAK2 and little to no detectable endogenous JAK2. Blotting cell lysates (Fig. 3A, bottom panel) or αmyc immunoprecipitates (data not shown) with αmyc revealed similar levels of overexpressed myc-APS in the different conditions.

To determine if the remaining APS binding to JAK2 (Y813F) is a consequence of the SH2 domain of APS binding to phosphotyrosines in JAK2 other than phosphotyrosine 813, we tested whether JAK2 would coimmunoprecipitate with an APS mutant that lacks a functional SH2 domain, APS (R437E). JAK2 was found to coimmunoprecipitate with myc-APS and with myc-APS (R437E) to similar extents (Fig. 3B, top panel), indicating that APS and JAK2 have one or more previously unidentified additional sites of interaction that involve neither phosphotyrosines in JAK2 nor the SH2 domain of APS and also that JAK2 binds to this site(s) with an affinity that approaches the level of binding to APS with an intact SH2 domain. To determine the function of these SH2 domain-dependent and -independent sites, we tested the effect of myc-APS and myc-APS(R437E) on the activity of JAK2 using a phosphospecific antibody (αpY1007/1008) to the activating tyrosines 1007/1008 within the kinase domain of JAK2 (6). Because the activating tyrosine 1007 must be phosphorylated for JAK2 to become fully active, as well as for tyrosine 1008 to become phosphorylated, an increase in signal obtained by blotting with αpY1007/1008 indicates an increase in the number of active JAK2 molecules. The second panel of Fig. 3B shows that coexpression of APS with JAK2 increases the number of active JAK2 molecules. In contrast, myc-APS (R437E) decreases the number of active JAK2 molecules, suggesting that binding to JAK2 by APS outside of tyrosine 813 is inhibitory. The contribution of endogenous JAK2 to the αpY1007/1008 signal is expected to be negligible compared to the contribution of overexpressed FLAG-JAK2, because the amount of endogenous JAK2 that was detected by immunoblotting with αJAK2 was negligible compared to that of overexpressed FLAG-JAK2 (Fig. 3A, middle panel). Consistent with this, we did not detect either an αpY1007/1008 or an αPY signal for endogenous JAK2, in the presence or absence of SH2-Bβ or APS, in other experiments using these COS7 cells (see Fig. 10; also data not shown).

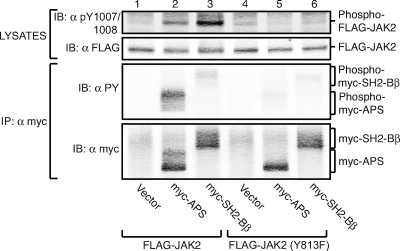

FIG. 10.

Amino acids 1 to 806 of JAK2 are dispensable for SH2-Bβ to increase the amount of active JAK2. (A) cDNA (1.0 μg) encoding either FLAG-JAK2 (lanes 1 and 2), JAK2 (Δ550-807)-HA (lanes 3 and 4), JAK2 (535-1129)-HA (lanes 5 and 6), or FLAG-JAK2 (797-1129) (lanes 7 and 8) was transfected into COS7 cells along with 2.0 μg cDNA encoding either prk5 myc (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or myc-SH2-Bβ (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Cell lysates were immunoblotted with αFLAG (second panel, lanes 1, 2, 7, and 8) or with αHA (third panel, lanes 3 to 6). The nitrocellulose was reprobed with αpY1007/1008 (top panel). Cell lysates were immunoblotted (IB) with αmyc (bottom panel). (B) Replicates for the experiment shown in panel A were quantified, normalized to expression levels of each corresponding JAK2 mutant, and expressed as percentages of JAK2/JAK2 mutant phosphorylation in the absence of SH2-Bβ (vector control). The data are expressed as means ± SE [n = 4, 3, 4, and 3 for FLAG-JAK2, JAK2 (Δ550-807)-HA, JAK2 (535-1129)-HA, and FLAG-JAK2 (797-1129), respectively]. Control levels are denoted by a dashed line.

Tyrosine 813 is required for APS to increase the amount of active JAK2.

We next examined whether APS enhancement of JAK2 activity and APS phosphorylation by JAK2 require binding of APS to tyrosine 813 in JAK2. We also directly compared the abilities of SH2-Bβ and APS to increase the number of active JAK2 molecules and to be phosphorylated by JAK2. FLAG-JAK2 or FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) was coexpressed with equal amounts of either myc-APS or myc-SH2-Bβ in COS7 cells. Immunoblotting cell lysates with αpY1007/1008 revealed that SH2-Bβ is more potent at increasing the number of active JAK2 molecules than APS (Fig. 4, top panel, lanes 1 to 3) (413% ± 95% versus 238% ± 38% of control [n = 3] for SH2-Bβ and APS, respectively). Mutating tyrosine 813 to phenylalanine abrogates the ability of SH2-Bβ to enhance the amount of active JAK2 protein (Fig. 4, top panel, lane 6), as reported previously (15). Mutating tyrosine 813 to phenylalanine also abrogates the ability of APS to enhance the amount of active JAK2 protein (Fig. 4, top panel, lane 5). In fact, overexpression of APS actually decreased (by 40% ± 2% [n = 3]) the αpY1007/1008 signal for JAK2 (Y813F), consistent with the effect seen with myc-APS (R437E), which was also shown to inhibit the activity of wild-type JAK2 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 4.

Tyrosine 813 of JAK2 is essential for APS to increase active JAK2. COS7 cells were transfected with 1.0 μg cDNA encoding either FLAG-JAK2 (lanes 1 through 3) or FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) (lanes 4 through 6), along with 2.0 μg cDNA encoding empty vector (lanes 1 and 4), myc-APS (lanes 2 and 5), or myc-SH2-Bβ (lanes 3 and 6). Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with αmyc, and immunoprecipitated proteins and aliquots of cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE. Cell lysates were immunoblotted (IB) with αpY1007/1008 (top panel) or αFLAG (second panel). The immunoprecipitated proteins were immunoblotted with αPY (third panel) or αmyc (bottom panel).

Immunoprecipitating myc-tagged APS and SH2-Bβ with αmyc and immunoblotting with αPY revealed that myc-APS is more heavily phosphorylated on tyrosines by JAK2 than SH2-Bβ (Fig. 4, third panel) (493% ± 155% of SH2-Bβ levels [n = 4]). Figure 4 also reveals that the tyrosyl phosphorylation of myc-APS, like that of myc-SH2-Bβ, is diminished when tyrosine 813 in JAK2 is mutated (Fig. 4, third panel). No tyrosyl phosphorylation of myc-APS or of myc-SH2-Bβ (reference 37 and data not shown) is detected when myc-APS or myc-SH2-Bβ, respectively, is coexpressed with kinase-dead JAK2 (K882E). These results further implicate tyrosine 813 of JAK2 as a binding site for APS and demonstrate its requirement for APS activation of JAK2 and maximal tyrosyl phosphorylation of APS.

Amino acids 407 to 621 of APS are sufficient for its enhancement of JAK2 activity.

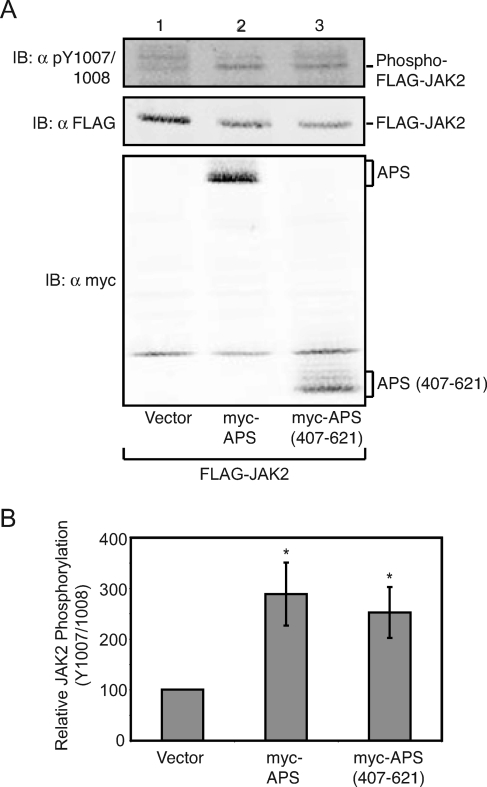

Because APS is a less potent stimulator of JAK2 than SH2-Bβ, binds more robustly to JAK2 (Y813F) than SH2-Bβ, and inhibits JAK2 (Y813F) while SH2-Bβ does not, we examined whether regions of APS outside the SH2 domain might actually inhibit JAK2. FLAG-JAK2 was coexpressed in COS7 cells with myc-tagged APS or APS (407-621), a truncated APS consisting of the SH2 domain and C terminus (schematic in Fig. 1C). Based on immunoblotting cell lysates with αpY1007/1008, wild-type APS and APS (407-621) increased the number of active JAK2 molecules to similar extents (Fig. 5A, top panel, and B), leading us to conclude that the N terminus of APS is not responsible for the low potency of APS compared to SH2-Bβ. The N terminus of APS possesses two potential dimerization domains, the first composed of amino acids 21 to 85 and reported to be required for APS to enhance JAK2 activity (4), and the second analogous to the dimerization domain between amino acids 100 and 243 of SH2-B (4, 32). Thus, the finding that APS (407-621) is as effective as full-length APS in increasing the number of active JAK2 molecules indicates that APS does not require either of its N-terminal dimerization domains to stimulate JAK2 activity.

FIG. 5.

Amino acids 407 to 621 are sufficient for APS to increase active JAK2. cDNA (1.0 μg) encoding FLAG-JAK2 was coexpressed with 2.0 μg of either empty prk5 myc vector (lane 1) or cDNA encoding myc-APS (lane 2) or myc-APS (407-621) (lane 3). Cell lysates were immunoblotted (IB) with αpY1007/1008 (top panel), αFLAG (FLAG-JAK2) (middle panel), or αmyc (bottom panel). (B) Replicates for the experiment shown in panel A were quantified, normalized to expression levels of JAK2, and expressed as percentages of JAK2 phosphorylation in the absence of APS (vector control). The data are expressed as means ± standard errors (SE) (n = 4). Conditions which yield statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in JAK2 phosphorylation at tyrosine 1007/1008 compared to vector control are marked with asterisks.

The SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is sufficient for SH2-Bβ to increase active JAK2.

Similar to APS, SH2-B has been hypothesized to activate JAK2 via SH2-B dimers binding to and dimerizing molecules of JAK2. A primary argument supporting the mechanism hypothesized by Nishi et al. that SH2-B-mediated JAK2 activation is a consequence of SH2-B dimerization stems from the observation that within the context of a bridging yeast trihybrid assay, SH2-B-enhanced dimerization of JAK2 requires the N-terminal dimerization domain of SH2-B (amino acids 24 to 85 of human SH2-Bβ) (25). To determine if a similar mechanism also applies to SH2-Bβ and JAK2 when expressed in mammalian cells, we determined (i) the minimum region of SH2-Bβ required to enhance JAK2 activity, (ii) the minimum region of SH2-Bβ required to increase JAK2 dimerization, and finally (iii) whether an SH2-Bβ molecule must be bound to each molecule of JAK2 to enhance JAK2 dimerization.

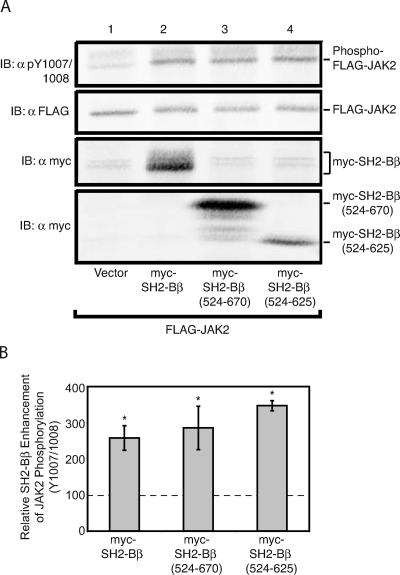

We first examined whether the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ alone is sufficient to enhance JAK2 activity. We expressed FLAG-JAK2 in COS7 cells with myc-SH2-Bβ, myc-SH2-Bβ (524-670) consisting of the SH2 domain and C terminus, or myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625) consisting of only the SH2 domain (see schematic in Fig. 1B). Immunoblotting cell lysates with αpY1007/1008 shows that FLAG-JAK2 expressed alone is constitutively active (Fig. 6A, top panel). As expected, coexpression of FLAG-JAK2 with myc-SH2-Bβ results in a substantial increase in the amount of active JAK2, as assessed by use of αpY1007/1008 (Fig. 6A, top panel, and B). A comparable increase in the amount of active JAK2 was observed using myc-tagged SH2-Bβ (524-670) or SH2-Bβ (524-625), despite, in the case of myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625), a consistently lower level of expression (Fig. 6A, lower two panels). These results showing that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is sufficient to mediate an increase in the amount of active JAK2 provide strong evidence that neither of the reported N-terminal dimerization domains of SH2-Bβ (25, 32) nor any unrecognized dimerization domain in the unique C terminus of the β isoform of SH2-B is required for SH2-Bβ to activate JAK2. Thus, it seems unlikely that dimerization of SH2-Bβ via its previously identified N-terminal dimerization domain(s) is the mechanism by which SH2-Bβ activates JAK2 in mammalian cells.

FIG. 6.

The SH2 domain of SH2-B is sufficient to increase active JAK2. cDNA (1.0 μg) encoding FLAG-JAK2 was coexpressed with 2.0 μg cDNA encoding either empty prk5 myc vector (lane 1), myc-SH2-Bβ (lane 2), myc-SH2-Bβ (524-670) (lane 3), or myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625) (lane 4). (A) Cell lysates were immunoblotted (IB) with αFLAG (second panel) and reprobed with αpY1007/1008 (top panel) and αmyc (bottom two panels). (B) Replicates for the experiment shown in panel A were quantified, normalized to expression levels of JAK2, and expressed as percentages of JAK2 phosphorylation in the absence of SH2-Bβ (vector control). The data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 4, 3, and 3). Conditions which yield statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in JAK2 phosphorylation of Y1007/1008 compared to the vector (no SH2-Bβ) control are marked with asterisks. Control levels are denoted by a dashed line.

Although we show that the SH2 domain of SH2-B is sufficient to increase JAK2 activity, to fully rule out the hypothesis that dimerization of SH2-B leads to concomitant dimerization and activation of JAK2, we examined the parameters required for SH2-Bβ to increase JAK2 dimerization. Specifically, we wanted to know if SH2-Bβ enhanced not only JAK2 activity but also JAK2 dimerization in a mammalian cell system, and if so, what the minimum region of SH2-Bβ required to do so would be and whether increased dimerization of JAK2 requires each JAK2 molecule in a JAK2 dimer to bind a molecule of SH2-Bβ.

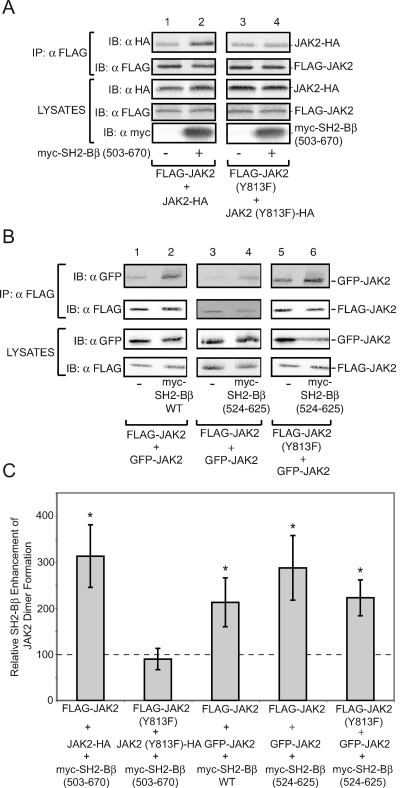

We first tested whether an SH2-Bβ mutant lacking its previously identified N-terminal dimerization domains, myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670), enhances dimerization of JAK2 in a mammalian expression system. FLAG-JAK2 and JAK2-HA were coexpressed with or without myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) in COS7 cells. FLAG-JAK2 was immunoprecipitated by αFLAG, and coprecipitating JAK2-HA was detected by Western blotting with αHA (Fig. 7A, top panel, lanes 1 and 2). JAK2-HA was found to coprecipitate with FLAG-JAK2, consistent with the presence of JAK2-HA:FLAG-JAK2 dimers. Coexpression of myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) with FLAG-JAK2 and JAK2-HA substantially increases the amount of JAK2-HA coprecipitating with FLAG-JAK2 (Fig. 7A, top panel, and C), suggesting that myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) increases the extent of JAK2 dimerization within a mammalian expression system.

FIG. 7.

SH2-Bβ enhances the dimerization of JAK2 in a manner independent of SH2-Bβ dimerization. (A) COS7 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg cDNA encoding FLAG-JAK2 and JAK2-HA (lanes 1 and 2) or FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) and JAK2-HA (Y813F) (lanes 3 and 4) along with 2.0 μg cDNA encoding empty vector (lanes 1 and 3) or myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) (lanes 2 and 4). Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with αFLAG and immunoblotted with αHA (top panel) and αFLAG (second panel). Cell lysates were immunoblotted with αHA (third panel), αFLAG (fourth panel), and αmyc (bottom panel). (B) cDNA (1.5 μg) encoding GFP-JAK2 was transfected into COS7 cells with 0.5 μg cDNA encoding FLAG-JAK2 (lanes 1 through 4) or FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) (lanes 5 and 6), along with 2.0 μg cDNA encoding empty vector (lanes 1, 3, and 5), myc-SH2-Bβ (lane 2), or myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625) (lanes 4 and 6). Proteins in cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with αFLAG and immunoblotted with αGFP (top panel) and αFLAG (second panel from top). Cell lysates were immunoblotted with αGFP (third panel from top) or αFLAG (bottom panel). Lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6 were obtained from the same gel. Lanes 3 and 4 were from a separate experiment and a separate gel. (C) Replicates for the experiments shown in panels A and B were quantified, and signal in the presence of SH2-Bβ (even-numbered lanes) was expressed as a percentage of the signal in the absence of SH2-Bβ (odd-numbered lanes). The data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 3). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in JAK2 dimerization compared to conditions without SH2-Bβ are marked with asterisks. Control levels are denoted by a dashed line. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot.

In a manner similar to that of JAK2-HA and FLAG-JAK2, JAK2-HA (Y813F) coprecipitated with FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) (Fig. 7A, top panel, lanes 1 and 3). However, myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) did not enhance the amount of JAK2 (Y813F)-HA coprecipitating with FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) (Fig. 7A, top panel, lanes 3 and 4, and C). These results indicate that the SH2-Bβ-dependent increase in JAK2-HA:FLAG-JAK2 dimers is dependent upon the binding of myc-SH2-Bβ to phosphotyrosine 813 of JAK2 but not on the N-terminal dimerization domains of SH2-Bβ.

We recognized that the C terminus of SH2-Bβ could contain a previously unidentified dimerization domain. We therefore sought to further define the minimal region of SH2-Bβ required to enhance JAK2 dimerization. We tested whether SH2-Bβ (524-625), encompassing only the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ, was capable of enhancing the dimerization of JAK2 by using FLAG- and GFP-tagged JAK2 and myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625). Overexpression of myc-SH2-Bβ and of myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625) caused similar increases in the number of GFP-JAK2:FLAG-JAK2 dimers (Fig. 7B, top panel, lanes 1 to 4, and C), suggesting that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is sufficient to enhance dimerization of JAK2.

The possibility that the SH2 domain of SH2-B contains a previously unidentified dimerization domain remained. myc-SH2-Bβ coprecipitates with GFP-SH2-Bβ; in contrast, myc-SH2-Bβ (503-670) does not coprecipitate with GFP-SH2-Bβ (505-670) (data not shown), consistent with the presence of dimerization domains in SH2-Bβ but a lack of a dimerization domain in SH2-Bβ (503-670). To check for the possibility that dimerization of the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is transient, is a low-affinity interaction, or is undetectable for some other reason, we examined whether the SH2-Bβ-mediated increase in JAK2 dimerization occurs if the JAK2 dimer can bind only a single SH2-Bβ. We coexpressed GFP-JAK2 with FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) in the presence or absence of myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625). Because the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ does not bind JAK2 (Y813F) (15), myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625) is expected to bind GFP-JAK2 but not FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F), making it impossible for any myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625) dimers that might form to recruit or colocalize FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) to GFP-JAK2. When myc-SH2-Bβ (524-625) is coexpressed with GFP-JAK2 and FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F), an SH2-Bβ-induced increase in the amount of GFP-JAK2 that coprecipitates with FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) is still observed (Fig. 7B, top panel, lanes 5 and 6, and C). These data indicate that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ is able to increase the number of GFP-JAK2:FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F) dimers without binding to FLAG-JAK2 (Y813F). Thus, SH2-Bβ-mediated enhancement of JAK2 dimerization does not require dimerization of SH2-Bβ, nor are both JAK2s in a JAK2 dimer required to bind SH2-Bβ.

Mutation of amino acids 809 to 811 of JAK2 increases active JAK2.

Having obtained strong evidence that SH2-Bβ activation of JAK2 does not require dimerization of SH2-Bβ, we considered whether SH2-Bβ might activate JAK2 by (i) recruiting an activator to JAK2; (ii) blocking the binding of an inhibitor to JAK2, thereby maintaining JAK2 in an active state; or (iii) inducing a conformational change in JAK2 to maintain JAK2 in an active state. The SH2 domain alone is sufficient for SH2-Bβ to enhance activation of JAK2 (Fig. 6), and JAK2 phosphorylates SH2-Bβ only at tyrosines outside of the SH2 domain (Y439 and Y494) (26). Therefore, it seems unlikely that SH2-Bβ enhances JAK2 activity by recruiting an activator of JAK2 to JAK2-SH2-Bβ complexes via an SH2-Bβ phosphotyrosine. Similarly, the finding that mutating the SH2-Bβ-binding site in JAK2 (tyrosine 813) responsible for SH2-Bβ-dependent JAK2 activation does not increase the basal activity of JAK2 (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 4) (15) argues against SH2-Bβ activating JAK2 by displacing an inhibitor that binds to the phosphorylated form of tyrosine 813. Mutating the binding site for such an inhibitor would be expected to prevent its binding to JAK2, thereby relieving its inhibition of JAK2 and increasing the basal activity of JAK2. If, however, such an inhibitor bound to the unphosphorylated form of tyrosine 813, then one could envision it retaining the ability to bind to JAK2 in which tyrosine 813 is mutated to a structurally similar amino acid (e.g., phenylalanine). Some PTB domain-containing proteins have been reported to bind to unphosphorylated tyrosine-containing motifs (45). Thus, it is intriguing that the amino acids N terminal to tyrosine 813 in JAK2 reside in an NPXY-like motif (TPDY813). This raises the possibility that the binding of SH2-Bβ via its SH2 domain to pY813ELL in JAK2 might enhance JAK2 activity by preventing the binding of a PTB domain containing inhibitor to TPDY813. We have shown previously that SH2-Bβ enhances the activity of JAK2 but not that of JAK3 or JAK1 (27). SH2-Bβ binds JAK3 at tyrosine 785, which corresponds to tyrosine 813 of JAK2 (15). Tantalizingly, the amino acid sequence surrounding tyrosine 813 in JAK2 (FRAVIRDLNSLFTPDY813ELL) is conserved in JAK3 (FRAVIRDLNSLISSDY785ELL), with the exception of three sequential amino acids (letters in italic type indicate the site of substitution as described below, and underlining indicates the NPXY motif). Two of these are among the four amino acids that make up this potential NPXY-like motif. To provide insight into whether SH2-Bβ might activate JAK2 by displacing a JAK2-specific PTB domain-containing inhibitor, we substituted amino acids FTP in JAK2 with ISS to make a JAK2 mutant that would not be expected to bind a PTB domain-containing inhibitor but would resemble JAK3 with respect to its SH2-Bβ-binding site. If our hypothesis were correct, then JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS) would be expected to exhibit increased basal activity due to the inability to bind the endogenous inhibitor, but SH2-Bβ would be unable to enhance the activity of JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS) due to the absence of a bound inhibitor for SH2-Bβ to displace. Consistent with this hypothesis, expression of FLAG-JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS) resulted in a substantial increase in the amount of active JAK2 compared to that of wild-type FLAG-JAK2 (Fig. 8A, top panel, lanes 1 and 3, and B). However, in contrast to what was predicted, coexpression of myc-SH2-Bβ with FLAG-JAK2 (FTP809-ISS811) resulted in a further increase in active JAK2 to a level above that observed with myc-SH2-Bβ and wild-type JAK2 (Fig. 8A, lanes 2 and 4, and B). To identify the precise residue(s) responsible for the enhanced activity observed with JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS), we made JAK2 mutants with single amino acid substitutions, FLAG-JAK2 (P811S), FLAG-JAK2 (T810S), and FLAG-JAK2 (F809I), and coexpressed these mutants with or without myc-SH2-Bβ in COS7 cells. Immunoblotting the lysates with αpY1007/1008 showed that no single amino acid substitution could replicate the increase in active JAK2 observed with FLAG-JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS), although subtle increases in active JAK2 were observed (Fig. 8A and B). Coexpression of myc-SH2-Bβ with each of these mutants increases active JAK2 at least to the level detected with FLAG-JAK2 plus myc-SH2-Bβ. The activity of FLAG-JAK2 (F809I) plus myc-SH2-Bβ was substantially above that obtained with FLAG-JAK2 plus myc-SH2-Bβ (Fig. 8A, lanes 2, 6, 8, and 10, and B). Thus, basal JAK2 activity appears to be suppressed by the FTP residues between amino acids 809 and 811 of JAK2, whereas the ability of SH2-Bβ to elevate JAK2 activity appears to be affected primarily by the F within the FTP motif.

FIG. 8.

Mutation of amino acids 809 to 811 of JAK2 enhances JAK2 activity. (A) cDNA (1.0 μg) encoding FLAG-JAK2 (lanes 1 and 2), FLAG-JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS) (lanes 3 and 4), FLAG-JAK2 (P811S) (lanes 5 and 6), FLAG-JAK2 (T810S) (lanes 7 and 8), or FLAG-JAK2 (F809I) (lanes 9 and 10) was cotransfected with 2.0 μg cDNA encoding prk5 myc (lanes 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9) or myc-SH2-Bβ (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) into COS7 cells. Cell lysates were immunoblotted (IB) with αFLAG (bottom panel), and the membrane was reprobed with αpY1007/1008 (top panel). (B) Replicates for the experiment shown in panel A were quantified, normalized to expression levels of JAK2, and expressed as percentages of JAK2 phosphorylation in the absence of SH2-Bβ (vector control). The data are expressed as means ± ranges (n = 2).

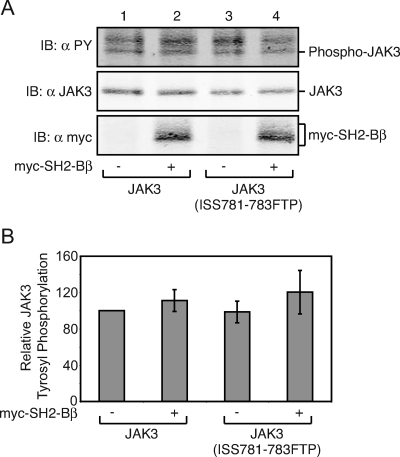

Because JAK2 (FTP809-811ISS) exhibits an increase in the amount of active JAK2, we examined whether the corresponding JAK3 mutant, JAK3 (ISS781-783FTP), would exhibit a decrease in active JAK3 and/or whether mutating these amino acids would render JAK3 susceptible to the positive regulatory effects of SH2-Bβ. JAK3 or JAK3 (ISS781-783FTP) was expressed with or without myc-SH2-Bβ in COS7 cells. Immunoblotting lysates of cells overexpressing JAK3 with αPY reveals that, like JAK2, JAK3 is constitutively active and phosphorylated (Fig. 9A, top panel, lane 1, and B) as previously reported (27). Coexpression of myc-SH2-Bβ with JAK3 does not enhance JAK3 phosphorylation (Fig. 9A, top panel, lane 2, and B). We observed no difference in phosphorylation when we expressed JAK3 (ISS781-783FTP) compared to JAK3 (Fig. 9A, top panel, lane 3, and B) and no change in phosphorylation when JAK3 (ISS781-783FTP) was coexpressed with myc-SH2-Bβ. This indicated to us that mutating amino acids 809 to 811 in JAK2 alters a specific regulatory region within JAK2 that does not exist in and cannot be easily introduced into JAK3. Taken together, these results do not support the hypothesis that SH2-Bβ competes directly for an inhibitor binding to tyrosine 813 in JAK2. Rather, they suggest to us that SH2-Bβ binding to JAK2 induces or maintains an active conformation of JAK2.

FIG. 9.

Mutation of amino acids 781 to 783 in JAK3 does not alter JAK3 activity. (A) cDNA (1.0 μg) encoding JAK3 (lanes 1 and 2) or JAK3 (ISS781-783FTP) (lanes 3 and 4) was cotransfected with 2.0 μg cDNA encoding prk5 myc (lanes 1 and 3) or myc-SH2-Bβ (lanes 2 and 4). Cell lysates were immunoblotted (IB) with αmyc (bottom panel) or αJAK3 (middle panel). The membrane was reprobed with αPY (top panel). (B) Replicates for the experiment shown in panel A were quantified, normalized to expression levels of JAK3, and expressed as percentages of JAK3 phosphorylation in the absence of SH2-Bβ (vector control). The data are expressed as means ± SE (n = 3). No significant difference in phosphorylation levels was detected between the conditions.

Amino acids 807 to 1129 of JAK2 are sufficient for SH2-Bβ to increase the number of active JAK2 molecules.

The JH2 domain of JAK2 (amino acids 545 to 824) has been shown to negatively regulate the activity of the kinase domain (JH1) of JAK2 (8, 40). Thus, we speculated that SH2-Bβ binding to the phosphorylated form of tyrosine 813, which resides within JH2 just next to the region linking JH2 to JH1 (schematic in Fig. 1A), might release the inhibition of JH1 by JH2. To test this, we examined whether SH2-Bβ would lose its ability to enhance JAK2 activity if we deleted the majority of the JH2 domain of JAK2. Immunoblotting lysates from cells expressing HA-tagged JAK2 (Δ550-807) (schematic in Fig. 1A) with αpY1007/1008 demonstrated that JAK2 (Δ550-807)-HA is constitutively active and migrates as two bands (Fig. 10A, top panel, lane 3). Coexpression of myc-SH2-Bβ with JAK2 (Δ550-807)-HA results in an enrichment of the upper pY1007/1008 band. This indicates that the JH2 domain is unnecessary for SH2-Bβ to increase the number of active JAK2 molecules. The fact that SH2-Bβ does not increase the amount of active JAK2 (Δ550-807)-HA as substantially as it increases the amount of active FLAG-JAK2 (Fig. 10A, top panel, lanes 1 to 4, and B) suggests that while the core ability of SH2-Bβ to increase active JAK2 exists in the absence of JH2, some residues within JH2 may be required for the full activity-enhancing effect of SH2-Bβ.

To assess whether the FERM domain or the SH2-like domain of JAK2 is required for SH2-Bβ to increase the activity of JAK2, we evaluated whether myc-SH2-Bβ could enhance the activity of JAK2 (535-1129), which lacks these domains (schematic in Fig. 1A). Western blotting with αpY1007/1008 revealed that SH2-Bβ also increases the number of active JAK2 (535-1129)-HA molecules (Fig. 10A, top panel, lanes 5 and 6), although not to the same extent as full-length JAK2.

The ability of SH2-Bβ to enhance binding of αpY1007/1008 to JAK2 (Δ550-807)-HA and JAK2 (535-1129)-HA suggests that amino acids 807 to 1129, encompassing the kinase domain (JH1) of JAK2 and the SH2-Bβ-binding site (Y813), are sufficient for SH2-Bβ to activate JAK2. Figure 10A, lanes 7 and 8, and B illustrate that myc-SH2-Bβ increases the amount of active FLAG-JAK2 (797-1129), leading us to conclude that myc-SH2-Bβ can increase the number of active JAK2 molecules in a manner that depends solely on the kinase domain of JAK2 and the SH2-Bβ-binding site. However, other residues in JAK2, including some present in the JH2 domain of JAK2 and some present in the FERM and SH2-like domains of JAK2, may be required for the full enhancing effects of SH2-Bβ.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we investigated the mechanism by which SH2-Bβ and its family member APS interact with and activate JAK2. For APS, we have provided direct evidence that APS and JAK2 form a complex involving phosphotyrosine 813 in JAK2 and the SH2 domain of APS. The use of immobilized peptides allowed us to show that APS binds directly and specifically to the phosphorylated form of tyrosine 813 in JAK2. Within the context of a mammalian expression system (COS7 cells), mutating tyrosine 813 in JAK2 or the SH2 domain in APS revealed that binding of APS to phosphotyrosine 813 via its SH2 domain is required for APS to activate JAK2 as well as for JAK2 to phosphorylate APS. It also revealed a second, previously unrecognized site of interaction between APS and JAK2 that does not require tyrosine 813 in JAK2 or an intact SH2 domain in APS. This second site of interaction does not require activation of JAK2 or any phosphorylated tyrosines in JAK2, since APS binds similarly to kinase-active JAK2 and kinase-inactive JAK2 (K882E), in which the critical lysine in the ATP-binding domain is mutated (unpublished data). Levels of coprecipitation of APS with JAK2 are similar for JAK2 and JAK2 (Y813F), indicating that binding to this second site of interaction is required for APS to bind to phosphotyrosine 813 in JAK2 or that APS binds JAK2 primarily through this second site. Binding of APS to this second site in JAK2 appears to inhibit JAK2, since mutating tyrosine 813 in JAK2 or the SH2 domain of APS results in an APS-induced decrease in the number of active JAK2 molecules. This finding is consistent with APS with a mutated SH2 domain inhibiting the tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 in HEK293 cells (4).

These findings provide insight into the mechanism behind our previous results showing that APS inhibits JAK2 at lower JAK2:APS ratios but stimulates JAK2 at higher JAK2:APS ratios (27). APS transiently overexpressed in COS7 cells expressing low endogenous levels of JAK2 was also found previously to inhibit GH stimulation of JAK2 and Stat5b phosphorylations (27), although APS stably overexpressed in 3T3-L1 cells expressing higher levels of endogenous JAK2 was reported to modestly enhance them (25). The JAK2:APS ratio-dependent inhibitory effect of APS on JAK2 led us to hypothesize (27) that APS inhibition of JAK2 requires the presence of another endogenous protein that is present in 293T cells in quantities sufficient to inhibit endogenous levels of JAK2 but not sufficient to inhibit overexpressed levels of JAK2. We had previously envisioned that protein being an inhibitor that bound to APS, such as the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl. APS is thought to recruit Cbl via phosphotyrosine 618 of APS, and APS in combination with Cbl has been reported to downregulate JAK2 signaling (46). However, in preliminary studies, overexpression of c-Cbl increased rather than decreased tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 in the presence or absence of APS (27). Furthermore, mutation of tyrosine 618 of APS to phenylalanine, which ought to eliminate binding of Cbl to APS, did not enhance the ability of APS to increase active JAK2 (unpublished observation). Our observation here that APS is more effective as an inhibitor of JAK2 under circumstances in which its phosphorylation by JAK2 is greatly reduced (i.e., by mutating tyrosine 813 in JAK2 to phenylalanine) suggests that if APS is recruiting an inhibitor, it is unlikely to be recruiting it via phosphorylated tyrosines within APS. Thus, instead of recruiting an inhibitor to JAK2, APS itself may inhibit JAK2 activity by binding through this second site. The finding of Nishi et al. (25) that this second site of interaction is not observed in a yeast two-hybrid assay raises the possibility that a rate-limiting accessory protein or posttranslational modification by a rate-limiting enzyme may be required for APS to bind to this second, inhibitory site of interaction in JAK2.

The findings with APS and SH2-Bβ reveal multiple similarities between the interactions of SH2-Bβ and APS with JAK2. Both bind directly to phosphorylated but not unphosphorylated tyrosine 813 in JAK2. For both, interaction with phosphotyrosine 813 in JAK2 requires an intact SH2 domain and results in an increase in the number of active JAK2 molecules. Activation does not require amino acids N terminal to the SH2 domain. In the case of SH2-Bβ, activation requires only the SH2 domain (the SH2 domain of APS could not be tested due to protein instability). Finally, both SH2-Bβ and APS contain at least one additional site of interaction with JAK2 that is inhibitory in nature. For SH2-Bβ, an additional site has been localized between amino acids 269 and 555 of rat SH2-Bβ. SH2-Bβ (1-555), which contains this site but lacks the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ, binds to JAK2 in a non-phosphotyrosine-dependent manner. When overexpressed, SH2-Bβ (1-555) inhibits the ability of coexpressed wild-type SH2-Bβ to activate JAK2 and enhance JAK2-dependent tyrosyl phosphorylation of overexpressed STAT5b. It also inhibits GH-induced nuclear translocation of STAT5b (36). Nothing is known about the site in JAK2 to which these amino acids bind or about the amino acids involved in any non-SH2-dependent interactions between APS and JAK2. However, these latter interactions appear to be inhibitory in nature, since mutating the SH2 domain of APS (Fig. 3C) or tyrosine 813 in JAK2 (Fig. 4) decreases the number of active JAK2 molecules, consistent with the finding that mutation of the SH2 domain of APS inhibits tyrosyl phosphorylation of JAK2 (4).

Despite the similarities between APS and SH2-Bβ, our direct comparisons using equivalent levels of expression of SH2-Bβ and APS revealed that APS and SH2-Bβ do not function identically vis-à-vis JAK2. SH2-Bβ increased active JAK2 to a greater extent than APS (Fig. 4). Based upon the levels of JAK2 (Y813F), relative to those of JAK2, that coprecipitate with APS (Fig. 3) or SH2-Bβ (15), the major portion of the binding affinity for JAK2 is contributed by the SH2 domain in SH2-Bβ, whereas the second binding site is the major contributor in APS. Furthermore, although mutated and/or truncated forms of SH2-Bβ and APS lacking the SH2 domain both inhibit JAK2, the binding of APS to JAK2 appears to be more inhibitory than the binding of SH2-Bβ, since APS inhibits the activity of JAK2 (Y813F), whereas SH2-Bβ does not (Fig. 4). The differential binding affinities of SH2-Bβ and APS for the phosphotyrosine 813-dependent and -independent sites in JAK2 might explain why the overexpression of SH2-Bβ enhanced GH stimulation of tyrosyl phosphorylation of endogenous JAK2 and (overexpressed) STAT5b in 293T cells but APS inhibited it (27). The findings that both SH2-B and APS are expressed fairly ubiquitously (5, 12, 13, 22-25, 29, 50, 51) and bind to JAK2 at tyrosine 813 suggest that SH2-Bβ and APS may compete with each other for binding to JAK2. Based upon our data, we would predict that in cells expressing similar levels of APS and SH2-Bβ, when JAK2 is in the inactive, nonphosphorylated state, JAK2 would be bound by APS in preference to SH2-Bβ, thereby helping to maintain JAK2 in an inactive state. However, when JAK2 becomes activated (e.g., in response to the binding of ligand to an associated cytokine receptor), the binding of SH2-Bβ to phosphotyrosine 813 in JAK2 would be expected to predominate, resulting in greater activation of JAK2.

Another way in which APS and SH2-Bβ differ is in their levels of tyrosyl phosphorylation by JAK2. Although SH2-Bβ is more effective than APS at activating JAK2, APS appears to be more highly phosphorylated than SH2-Bβ by JAK2. This could be a consequence of the tyrosines in APS that serve as JAK2 substrates being more numerous than those in SH2-Bβ, better JAK2 substrates, or less susceptible to dephosphorylation. Alternatively, the tyrosines in APS could have a higher affinity for the αPY antibody than the sites in SH2-Bβ. The JAK2 sites of phosphorylation in SH2-Bβ have been identified by phosphopeptide mapping as tyrosines 439 and 494 and implicated in SH2-Bβ enhancement of GH-dependent membrane ruffling of 3T3-F442A cells (26). However, downstream binding partners of phosphotyrosines 439 and 494 have not yet been identified. The tyrosines in APS that serve as JAK2 substrates have not yet been identified. However, tyrosine 618 in APS is likely to be a JAK2 substrate, since overall tyrosyl phosphorylation of APS by JAK2 is decreased when tyrosine 618 is mutated (data not shown). Furthermore, phosphotyrosine 618 has been implicated as a docking site for Cbl (20), and Cbl has been implicated in APS-induced downregulation of erythropoietin-activated Stat5 (46). Notably, a tyrosine equivalent to 618 in APS is not present in SH2-Bβ, and tyrosines corresponding to tyrosines 439 and 494 in SH2-Bβ do not exist in APS. Thus, the phosphorylated tyrosines in APS and SH2-Bβ would be expected to recruit different signaling proteins to JAK2 and thereby activate different signaling pathways.

Our studies concerning the molecular basis for how SH2-Bβ enhances JAK2 activity demonstrated that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ alone enhances JAK2 activity to a level equal to the enhancement seen with full-length SH2-Bβ. However, our preliminary studies (data not shown) revealing an inability of differentially tagged (myc- and GFP-tagged) SH2-Bβ (503-670) to coprecipitate, as well as previous gel filtration chromatography studies (10), coimmunoprecipitation experiments (32), and yeast two-hybrid data (25), all indicate that the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ behaves as a monomer. Further, experiments using the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ and differentially tagged JAK2 and JAK2 (Y813F) demonstrated that both JAK2 molecules in the JAK2 dimer need not be able to bind SH2-Bβ for SH2-Bβ (or the SH2 domain alone) to enhance JAK2 dimerization and activity. Taken together, these findings argue strongly against activation of JAK2 by SH2-Bβ being a consequence of two molecules of SH2-Bβ bringing together two JAK2 proteins as a consequence of dimerization of SH2-Bβ through the N-terminal dimerization domain identified by Nishi et al. (25), the N-terminal dimerization domain reported by Qian and Ginty (32), or any hypothetical dimerization domains in the SH2 domain or in the unique C terminus of the β isoform of SH2-B. Because SH2-Bβ binding to phosphorylated tyrosine 813 is required for SH2-Bβ to activate JAK2, and because tyrosine 813 appears to become phosphorylated only after JAK2 is activated, we think that while the ability of SH2-B to form dimers would facilitate the binding of two SH2-Bβ proteins to preformed dimers of JAK2, SH2-Bβ-dependent activation of JAK2 is not a consequence of SH2-Bβ dimerization.

Because our data do not support a requisite role for SH2-Bβ dimerization in its ability to activate JAK2, we looked to other explanations for how SH2-Bβ might activate JAK2. The finding that the SH2 domain is sufficient for SH2-Bβ to activate JAK2 combined with the previous finding that the JAK2-dependent phosphorylation sites in SH2-Bβ lie outside of the SH2 domain (26) ruled out the possibility that SH2-Bβ could be activating JAK2 by recruiting an activator of JAK2 that bound to phosphorylated tyrosines in SH2-Bβ. While we think it unlikely, our results do not rule out the possibility that SH2-B recruits an activator of JAK2 that binds to a site in the SH2 domain of SH2-Bβ that does not involve a phosphorylated tyrosine.

Our data also do not support the hypothesis that SH2-Bβ competes for an inhibitor of JAK2 for binding at tyrosine 813. The previous finding mentioned above (15) and confirmed here that mutation of tyrosine 813 to phenylalanine does not stimulate JAK2 argues against SH2-Bβ displacing an endogenous inhibitor bound to phosphotyrosine 813. Our finding that mutating three of the four amino acid residues N terminal to tyrosine 813 increases basal JAK2 activity to levels close to those seen with wild-type JAK2 and SH2-Bβ is consistent with an endogenous JAK2 inhibitor binding to unphosphorylated tyrosine (and also phenylalanine) 813. However, the finding that SH2-Bβ substantially activates this mutated JAK2 argues against SH2-Bβ activating JAK2 by displacing such a hypothetical endogenous inhibitor. Also arguing against SH2-Bβ competing for a hypothetical endogenous inhibitor that binds to tyrosine 813, either phosphorylated or unphosphorylated, is our finding that mutating three of the four amino acids N terminal to the tyrosine in JAK3 that corresponds to tyrosine to 813 in JAK2 to the equivalent sequence in JAK2 (resulting in a 19-amino-acid identity around tyrosine 813 in JAK2 and 785 in JAK3) did not decrease basal JAK3 activity or allow SH2-Bβ to activate JAK3.

Our data are most consistent with the hypothesis that the binding of SH2-Bβ increases the activity of JAK2 by causing a conformational change that makes JAK2 more active or that stabilizes JAK2 in an active conformation. This would also be consistent with the finding of Nishi et al. (25) that direct addition of SH2-Bβ (highly purified from Escherichia coli) to JAK2 (substantially purified from HEK293 cells) stimulates JAK2 activity. Little structural knowledge of JAK2 exists, limiting speculation as to the mechanisms by which SH2-Bβ may alter JAK2 conformations. Although the crystal structure of the kinase domain of JAK2 has recently been published (21), the crystallized domain does not contain tyrosine 813 in JAK2. The pseudokinase (JH2) domain of JAK2 has been shown to negatively regulate the kinase domain by lowering the Vmax of the kinase (41). The fact that the binding site for SH2-Bβ (i.e., Y813) is situated at the C terminus of the JH2 domain, adjacent to the region linking the JH2 and JH1 domains, suggested that SH2-Bβ may serve either to relax the inhibition of JH2 on JH1 or to stabilize the active conformation of JH1 and JH2. Results shown in Fig. 10 demonstrate that SH2-Bβ is capable of increasing the number of active JAK2 molecules in a manner independent of JH2-inhibitory regions. However, maximal SH2-Bβ-dependent enhancement of JAK2 activity occurs with full-length JAK2. Thus, amino acids 809 to 811 in JAK2 would appear to be a critical component of a larger regulatory region within JAK2, most likely including amino acids within the JH1 domain, the JH2 domain, and possibly the FERM domain.

In summary, we show that APS, like SH2-Bβ, binds to JAK2 at multiple sites. Binding to phosphotyrosine 813 in JAK2 is essential for both SH2-Bβ and APS to increase the number of active JAK2 molecules. Binding of APS to regions other than phosphotyrosine 813 inhibits JAK2 and may require an accessory protein. Using a series of truncations and mutations, we provide strong evidence that dimerization of SH2-Bβ (and most likely of APS) is not required to enhance JAK2 activity. SH2-Bβ-induced increases in JAK2 dimerization require only the SH2 domain and only one SH2-Bβ to be bound to a JAK2 dimer. Our data do not support the hypothesis that SH2-Bβ recruits an activator to JAK2 or displaces a JAK2 inhibitor from JAK2. Rather, our data favor the hypothesis that the dramatic elevation in JAK2 activity detected when SH2-Bβ is present stems from the ability of SH2-Bβ to increase the number of active JAK2 molecules by causing or stabilizing a conformational change in JAK2 that maintains JAK2 in an active, dimerized state. Because tyrosine 813 in endogenous JAK2 is phosphorylated in response to GH (15) and overexpression of SH2-Bβ enhances GH stimulation of endogenous JAK2 (25, 35), we predict that SH2-Bβ enhances GH-activated JAK2 by a similar mechanism, i.e., by binding to phosphorylated tyrosine 813 in GH-activated JAK2 and causing or stabilizing a conformational change in JAK2 that helps maintain JAK2 in an active, dimerized state.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DK34171 and DK54222 (to C.C.-S.). J.H.K. was supported by Predoctoral Fellowship of the Cellular and Molecular Approaches to Systems and Integrative Biology Training Grant T32-GM08322 and the University of Michigan Medical Scientist Training Program (NIH T32 GM07863). cDNA sequencing and synthesis of the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated peptides were supported by the Cellular and Molecular Biology Core and the Protein Core, respectively, of the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center (P60-DK20572), by the University of Michigan Multipurpose Arthritis Center (P60-AR20557), and by the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center (NIH P30 CA46592).

We thank Xiaqing Wang for support and assistance with DNA constructs, Lawrence S. Argetsinger for critical comments on the manuscript and help with the figures, and Barbara Hawkins for assistance with the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown, R. J., J. J. Adams, R. A. Pelekanos, Y. Wan, W. J. McKinstry, K. Palethorpe, R. M. Seeber, T. A. Monks, K. A. Eidne, M. W. Parker, and M. J. Waters. 2005. Model for growth hormone receptor activation based on subunit rotation within a receptor dimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:814-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, C., and H. Okayama. 1987. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:2745-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darnell, J. E., Jr., I. M. Kerr, and G. R. Stark. 1994. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 264:1415-1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhe-Paganon, S., E. D. Werner, M. Nishi, L. Hansen, Y. I. Chi, and S. E. Shoelson. 2004. A phenylalanine zipper mediates APS dimerization. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:968-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duan, C., H. Yang, M. F. White, and L. Rui. 2004. Disruption of SH2-B causes age-dependent insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:743507443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng, J., B. A. Witthuhn, T. Matsuda, F. Kohlhuber, I. M. Kerr, and J. N. Ihle. 1997. Activation of Jak2 catalytic activity requires phosphorylation of Y1007 in the kinase activation loop. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:2497-2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank, S. J., G. Gilliland, A. S. Kraft, and C. S. Arnold. 1994. Interaction of the growth hormone receptor cytoplasmic domain with the JAK2 tyrosine kinase. Endocrinology 135:2228-2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank, S. J., W. Yi, Y. Zhao, J. F. Goldsmith, G. Gilliland, J. Jiang, I. Sakai, and A. S. Kraft. 1995. Regions of the JAK2 tyrosine kinase required for coupling to the growth hormone receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 270:14776-14785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins, D. G., J. D. Thompson, and T. J. Gibson. 1996. Using CLUSTAL for multiple sequence alignments. Methods Enzymol. 266:383-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, J., J. Liu, R. Ghirlando, A. R. Saltiel, and S. R. Hubbard. 2003. Structural basis for recruitment of the adapter protein APS to the activated insulin receptor. Mol. Cell 12:1379-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, X., Y. Li, K. Tanaka, K. G. Moore, and J. I. Hayashi. 1995. Cloning and characterization of Lnk, a signal transduction protein that links T-cell receptor activation signal to phospholipase C γ 1, Grb2, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11618-11622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iseki, M., S. Takaki, and K. Takatsu. 2000. Molecular cloning of the mouse APS as a member of the Lnk family adaptor proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 272:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotani, K., P. Wilden, and T. S. Pillay. 1998. SH2-Bα is an insulin-receptor adapter protein and substrate that interacts with the activation loop of the insulin-receptor kinase. Biochem. J. 335:103-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kralovics, R., F. Passamonti, A. S. Buser, S. S. Teo, R. Tiedt, J. R. Passweg, A. Tichelli, M. Cazzola, and R. C. Skoda. 2005. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:1779-1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurzer, J. H., L. S. Argetsinger, Y.-J. Zhou, J.-L. Kouadio, J. J. O'Shea, and C. Carter-Su. 2004. Tyrosine 813 is a site of JAK2 autophosphorylation critical for activation of JAK2 by SH2-Bβ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:4557-4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacronique, V., A. Boureux, V. D. Valle, H. Poirel, C. T. Quang, M. Mauchauffe, C. Berthou, M. Lessard, R. Berger, J. Ghysdael, and O. A. Bernard. 1997. A TEL-JAK2 fusion protein with constitutive kinase activity in human leukemia. Science 278:1309-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonard, W. J., and J. J. O'Shea. 1998. Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16:293-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine, R. L., M. Wadleigh, J. Cools, B. L. Ebert, G. Wernig, B. J. Huntly, T. J. Boggon, I. Wlodarska, J. J. Clark, S. Moore, J. Adelsperger, S. Koo, J. C. Lee, S. Gabriel, T. Mercher, A. D'Andrea, S. Frohling, K. Dohner, P. Marynen, P. Vandenberghe, R. A. Mesa, A. Tefferi, J. D. Griffin, M. J. Eck, W. R. Sellers, M. Meyerson, T. R. Golub, S. J. Lee, and D. G. Gilliland. 2005. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell 7:387-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, M., D. Ren, M. Iseki, S. Takaki, and L. Rui. 2006. Differential role of SH2-B and APS in regulating energy and glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology 147:2163-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, B. P., and K. Burridge. 2000. Vav2 activates Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA downstream from growth factor receptors but not β1 integrins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:7160-7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucet, I. S., E. Fantino, M. Styles, R. Bamert, O. Patel, S. E. Broughton, M. Walter, C. J. Burns, H. Treutlein, A. F. Wilks, and J. Rossjohn. 2006. The structural basis of Janus kinase 2 inhibition by a potent and specific pan-Janus kinase inhibitor. Blood 107:176-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minami, A., M. Iseki, K. Kishi, M. Wang, M. Ogura, N. Furukawa, S. Hayashi, M. Yamada, T. Obata, Y. Takeshita, Y. Nakaya, Y. Bando, K. Izumi, S. A. Moodie, F. Kajiura, M. Matsumoto, K. Takatsu, S. Takaki, and Y. Ebina. 2003. Increased insulin sensitivity and hypoinsulinemia in APS knockout mice. Diabetes 52:2657-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moodie, S. A., J. Alleman-Sposeto, and T. A. Gustafson. 1999. Identification of the APS protein as a novel insulin receptor substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 274:11186-11193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelms, K., T. J. O'Neill, S. Li, S. R. Hubbard, T. A. Gustafson, and W. E. Paul. 1999. Alternative splicing, gene localization, and binding of SH2-B to the insulin receptor kinase domain. Mamm. Genome 10:1160-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishi, M., E. D. Werner, B. C. Oh, J. D. Frantz, S. Dhe-Paganon, L. Hansen, J. Lee, and S. E. Shoelson. 2005. Kinase activation through dimerization by human SH2-B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:2607-2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien, K. B., L. S. Argetsinger, M. Diakonova, and C. Carter-Su. 2003. YXXL motifs in SH2-Bβ are phosphorylated by JAK2, JAK1, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor and are required for membrane ruffling. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11970-11978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Brien, K. B., J. J. O'Shea, and C. Carter-Su. 2002. SH2-B family members differentially regulate JAK family tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8673-8681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohtsuka, S., S. Takaki, M. Iseki, K. Miyoshi, N. Nakagata, Y. Kataoka, N. Yoshida, K. Takatsu, and A. Yoshimura. 2002. SH2-B is required for both male and female reproduction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:3066-3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osborne, M. A., S. Dalton, and J. P. Kochan. 1995. The yeast tribrid system—genetic detection of trans-phosphorylated ITAM-SH2-interactions. Bio/Technology 13:1474-1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Shea, J. J., M. Gadina, and R. D. Schreiber. 2002. Cytokine signaling in 2002: new surprises in the Jak/Stat pathway. Cell 109(Suppl.):S121-S131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peeters, P., S. D. Raynaud, J. Cools, I. Wlodarska, J. Grosgeorge, P. Philip, F. Monpoux, L. Van Rompaey, M. Baens, H. Van den Berghe, and P. Marynen. 1997. Fusion of TEL, the ETS-variant gene 6 (ETV6), to the receptor-associated kinase JAK2 as a result of t(9;12) in a lymphoid and t(9;15:12) in a myeloid leukemia. Blood 90:2535-2540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian, X., and D. D. Ginty. 2001. SH2-B and APS are multimeric adapters that augment TrkA signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1613-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qian, X., A. Riccio, Y. Zhang, and D. D. Ginty. 1998. Identification and characterization of novel substrates of Trk receptors in developing neurons. Neuron 21:1017-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren, D., M. Li, C. Duan, and L. Rui. 2005. Identification of SH2-B as a key regulator of leptin sensitivity, energy balance and body weight in mice. Cell Metab. 2:95-104. [Online.] doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rui, L., and C. Carter-Su. 1999. Identification of SH2-Bβ as a potent cytoplasmic activator of the tyrosine kinase Janus kinase 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:7172-7177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rui, L., D. R. Gunter, J. Herrington, and C. Carter-Su. 2000. Differential binding to and regulation of JAK2 by the SH2 domain and N-terminal region of SH2-Bβ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3168-3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rui, L., L. S. Mathews, K. Hotta, T. A. Gustafson, and C. Carter-Su. 1997. Identification of SH2-Bβ as a substrate of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 involved in growth hormone signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6633-6644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell, S. M., J. A. Johnston, M. Noguchi, M. Kawamura, C. M. Bacon, M. Friedmann, M. Berg, D. W. McVicar, B. A. Witthuhn, and O. Silvennoinen. 1994. Interaction of IL-2R beta and gammac chains with Jak1 and Jak3: implications for XSCID and XCID. Science 266:1042-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saharinen, P., and O. Silvennoinen. 2002. The pseudokinase domain is required for suppression of basal activity of Jak2 and Jak3 tyrosine kinases and for cytokine-inducible activation of signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47954-47963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]