Abstract

Recent research has revealed a conserved role for the actin cytoskeleton in the regulation of aging and apoptosis among eukaryotes. Here we show that the stabilization of the actin cytoskeleton caused by deletion of Sla1p or End3p leads to hyperactivation of the Ras signaling pathway. The consequent rise in cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels leads to the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and cell death. We have established a mechanistic link between Ras signaling and actin by demonstrating that ROS production in actin-stabilized cells is dependent on the G-actin binding region of the cyclase-associated protein Srv2p/CAP. Furthermore, the artificial elevation of cAMP directly mimics the apoptotic phenotypes displayed by actin-stabilized cells. The effect of cAMP elevation in inducing actin-mediated apoptosis functions primarily through the Tpk3p subunit of protein kinase A. This pathway represents the first defined link between environmental sensing, actin remodeling, and apoptosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has emerged as an important model organism for the study of eukaryotic aging and apoptosis. This yeast exhibits a finite replicative capacity and chronological aging characteristics which are highly analogous to those observed in higher eukaryotes (20). In addition, aged yeast cells die in a predictable manner, exhibiting many of the hallmarks of apoptosis (16, 18). A crucial factor in both cellular aging and apoptosis is the generation, release, and buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the mitochondria (reviewed in reference 2). The unregulated accumulation of ROS has been linked to the development of a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases (5, 26), to cardiovascular disease, and to tumor formation (reviewed in reference 9). The elucidation of pathways which lead to ROS production and accumulation in eukaryotic cells is therefore of great significance.

Evidence from our laboratory has demonstrated that a strong correlation between ROS accumulation, apoptosis, and the dynamic state of the actin cytoskeleton exists in yeast (14). We have also shown that an actin-mediated apoptosis pathway exists in yeast which is likely to arise from a tight interaction between the cytoskeleton and the Ras signaling pathway. Yeast Ras proteins are functionally interchangeable homologues of mammalian Ras. In both yeast and mammalian cells, the expression of constitutively active Ras, Rasala18val19 and Rasval12, respectively, results in the accumulation of ROS and a reduction of the life span (15, 29). The regulation of Ras signaling has also been shown to modulate apoptosis in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans (25). In yeast, Ras and cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling coordinates cell growth and proliferation with nutritional sensing. The production of the secondary messenger cAMP is carried out by an adenylyl cyclase, Cyr1p, and can be stimulated by two mechanisms. One is the G protein-coupled receptor GPR1-GPA2 system (34). The second is through binding of GTP-bound Ras and adenylyl cyclase-associated (Srv2p/CAP) proteins (35). Elevation of cAMP levels leads to dissociation of the protein kinase A (PKA) regulator Bcy1p to yield active A kinases which elicit alterations in processes such as cell cycle progression and stress responses (32). There are three A kinase catalytic subunits in yeast, encoded by TPK1, -2, and -3, which display overlapping and separable functions in response to activation by cAMP (4, 27). However, some unique activities have been attributed to individual subunits; for example, it was recently shown that the loss of Tpk3p function specifically results in a significant reduction in respiratory function (4). These data provide evidence to link Ras signaling and mitochondrial function, which in turn impact on oxidative stress management and the regulation of yeast aging (15, 19).

Mutations in certain actin regulatory proteins (End3p and Sla1p) lead to the accumulation of aggregates of F-actin and the development of apoptosis. Typically, mutant cells display a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and a massive increase in ROS levels (13, 14). These effects can be prevented by overexpressing the negative regulator of Ras signaling, PDE2 (13). Pde2p catalyzes the hydrolysis of cAMP to AMP, thereby downregulating signal transduction through the Ras pathway. A key question remaining is how the Ras pathway is activated in cells and whether changes in actin dynamics can provide a physiological trigger for Ras activation. A potential candidate to link actin dynamics to Ras signaling is the protein Srv2p/CAP. Srv2p/CAP is a highly conserved protein that is able to bind to actin, regulate actin dynamics, and facilitate signaling through the Ras pathway (12). Srv2p/CAP binds preferentially to ADP-G-actin via its C-terminal domain (23) and can associate with actin filaments through an interaction between a proline region and the SH3 domain of actin binding protein 1 (Abp1p) (11). The N terminus of Srv2p/CAP has been shown to facilitate the constitutive signaling of the rasala18val19 allele in S. cerevisiae (12). Srv2p/CAP is therefore an attractive candidate to link Ras signaling to actin reorganization. However, clear evidence for this link has been absent. Indeed, previous research has demonstrated that the adenylyl cyclase and actin regulatory functions of Srv2p/CAP are separable and distinct (12). Here we present data which demonstrate that Srv2p/CAP-dependent actin stabilization leads to hyperactivation of the Ras signaling pathway. Furthermore, the resultant elevation of cAMP leads to further stabilization of actin structures and to cell death exhibiting characteristic features of apoptosis. We also show that this pathway signals through a novel function of PKA, primarily through the Tpk3p subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

Unless stated otherwise, cells were grown in a rotary shaker at 30°C in liquid YPAD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, and 2% glucose supplemented with 40 μg/ml adenine). The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. matα strains deleted for PDE2 (KAY812), TPK1 (KAY818), TPK2 (KAY819), and TPK3 (KAY867) were obtained from open biosystems (accession numbers YOR360C, YJL164C, YPL203W, and YKL166C, respectively). PDE2 was deleted in KAY818, KAY819, and KAY867 by using the oligonucleotides oKA479 (5′ATGTCCACCCTTTTTCTGATTGGAATACACGAGATTGAGAAATCTCAAACCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA3′) and oKA480 (5′CTATTGTGGTTTCTTGTGTTCATCCAGTATTCTTTATTGATTTTGACATGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC3′). SRV2 and TPK3 were deleted in KAY450 by using the oligonucleotides oKA482 (5′ATGCCTGACTCTAAGTACACAATGCAAGGTTATAACCTTGTTAAGCTATTCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA3′) and oKA483 (5′TTAACCAGCATGTTCGAAAACAGCAGATTTGAACTTACCATCAGCGAAGCGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC3′) (SRV2 deletion) or oKA509 (5′ATGTATGTTGATCCGATGAACAACAATGAAATCAGGAAATTAAGCATTACCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA3′) and oKA510 (5′TCTTTCATTAAATCCATATATGGATCCTCCCCTTGAATTCCATAGTTGAAGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC3′) (TPK3 deletion). All deletions were generated using a HIS3 replacement vector as previously described (21). Plasmids used to express Srv2p/CAP and various truncations have been described previously (12). The plasmid used to express Pep4p-enhanced green fluorescent protein (Pep4p-EGFP) was also described previously (22).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| KAY446 | matahis3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | Research Genetics |

| KAY450 | mataΔend3::KanMx his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | Research Genetics |

| KAY36 | matahis3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 lys2-801am | D. Drubin (UC Berkeley) (strain DDY903) |

| KAY350 | matahis3-Δ200 leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 lys2-801am sla1 Δ118-511::HIS3 sla1-Δ2::LEU2 | C. Gourlay et al. |

| KAY812 | mataΔpde2::KanMx his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | Research Genetics |

| KAY818 | mataΔtpk1::KanMx his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | Research Genetics |

| KAY819 | mataΔtpk2::KanMx his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | Research Genetics |

| KAY867 | mataΔtpk3::KanMx his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | Research Genetics |

| KAY888 | mataΔtpk1::KanMx Δpde2::HIS3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | This study |

| KAY889 | mataΔtpk2::KanMx Δpde2::HIS3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | This study |

| KAY890 | mataΔtpk3::KanMx Δpde2::HIS3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | This study |

| KAY891 | mataΔend3::KanMx Δsrv2::HIS3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | This study |

| KAY892 | mataΔend3::KanMx Δtpk3::HIS3 his3Δ1 leu2Δ met15Δ ura3Δ | This study |

Active Ras2 assays.

Pull-down assays for active Ras2p in cell extracts were performed by using a purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged active Ras binding domain (RBD) as previously described (6). Ras2p was detected on Western blots by using goat anti-Ras2 polyclonal antibodies at a dilution of 1:250 (SC-6759; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Active Ras2p was detected in vivo by using an overlay approach, as follows. Cells were grown overnight to stationary phase before being fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 1 h. The fixed cells were then incubated with GST-RBD plus 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin in 1× phosphate-buffered saline for 1 h at room temperature. GST-RBD was then detected using a polyclonal anti-GST antibody (1:100 dilution). Cells were then treated as for immunofluorescence assays, as previously described (14).

cAMP measurements.

Cells were grown overnight in YPAD to early stationary phase, and the cell density was determined in triplicate with a Schärfe Systems TT cell counter and analyzer. One milliliter of culture was then harvested by centrifugation. Extracts were prepared by resuspending the pellet in 1 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid and freeze-thawing the suspension three times. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 2 min, the supernatant was removed and extracted five times with 2 ml of ether. The aqueous fraction was then dried in a speed vacuum and resuspended in assay buffer. The samples were assayed using a cAMP Biotrak enzyme immunoassay system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All samples were performed in triplicate, and final calculations take into account variations in the starting cell number.

Latrunculin A treatment and halo sensitivity assay.

Latrunculin A (LAT-A) was added to YPAD medium to a final concentration of 60 μM and inoculated with KAY450 (Δend3) cells. The same inoculum was applied to untreated YPAD medium. Cultures were then grown overnight to early stationary phase, and their cell densities were assessed using a Schärfe Systems TT cell counter and analyzer. For LAT-A halo assays, 10 μl overnight culture was added to 2 ml yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) and 2 ml 1% sterile agar. The cells were poured onto a YPAD plate and cooled, and then sterile disks containing LAT-A at a concentration of 5 mM were placed onto each plate. Experiments were carried out in triplicate. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days.

Apoptosis marker detection using flow cytometry.

To assess ROS, cells were grown overnight to stationary phase in the presence of 5 μg/ml 2′,7′-dichloro dihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFDA; Molecular Probes). The mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was assessed in cells by the addition of 3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (DiOC6) to the medium to a final concentration of 20 ng/ml and incubation for 20 min with rotation at 30°C in the dark. Propidium iodide uptake was assessed by its addition to cultures at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml and incubation for 20 min. Cells were vortexed briefly prior to analysis, and fluorescence was analyzed using a cyan ADP flow cytometer (Dako Cytomation). The resultant data were processed with Summit software (Dako Cytomation).

Viability assays.

Viability assays were carried out as previously described (13). Briefly, cells were grown in liquid YPD medium. Cell numbers were determined in triplicate with a Schärfe Systems TT cell counter and analyzer. Serial dilutions were plated onto YPD agar plates, and the number of surviving colonies was counted. Percent viability was determined by dividing the number of surviving colonies by the calculated number of plated colonies.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Rhodamine-phalloidine and DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining was performed as previously described for F-actin (14). Cells were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy as described previously (14). Mitochondria were visualized using DiOC6 (Molecular Probes) at 20 ng/ml as previously described (14). Antibodies used to detect Srv2p (a gift from D. Drubin, University of California at Berkeley, CA) and Cyr1p (a gift from T. Kataoka, Department of Physiology II, Kobe University School of Medicine, Japan) were used for immunofluorescence at a dilution of 1:50. The secondary antibodies used were fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies (Vector Laboratories) at a 1:100 dilution.

RESULTS

Ras signaling is hyperactive in mutant cells with stabilized actin.

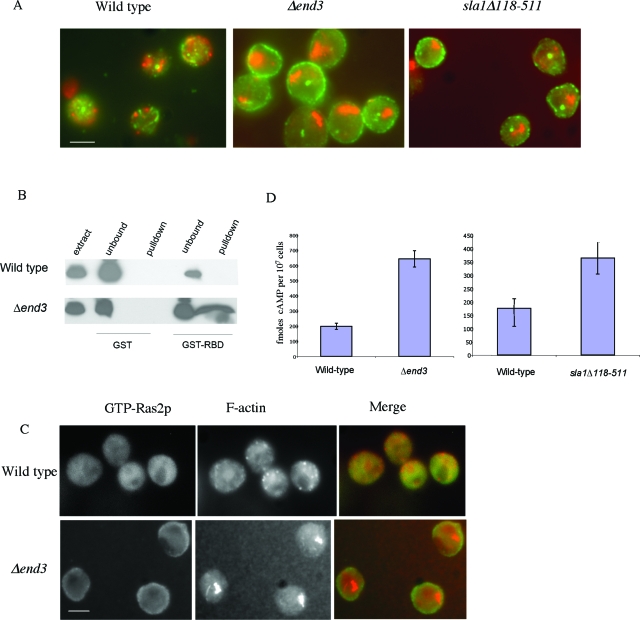

Mutations in certain actin regulatory proteins which stabilize the actin cytoskeleton, such as deletion of End3p (Δend3) or the actin regulatory region of Sla1p (sla1Δ118-511), result in the accumulation of large aggregates of F-actin and a massive accumulation of ROS in the stationary phase of growth (13). Stationary phase is a quiescent state, which yeast cells enter as they exhaust the available nutrient supply. It is characterized by morphological and biochemical changes, such as cell cycle arrest, cell wall thickening, acquisition of thermotolerance, and accumulation of reserve carbohydrates. The accumulation of ROS and the cell death that occur in actin-stabilized stationary-phase cells can be prevented by overexpression of the high-affinity cAMP phosphodiesterase Pde2 (13). Since PDE2 is a negative regulator of Ras signaling, we wished to establish the status of this pathway in stationary-phase actin-stabilized cells. Initially, we examined the localization of the regulatory GTPase Ras2p by immunofluorescence. In wild-type cells, Ras2p is cytoplasmically distributed and shows little colocalization with the cortical F-actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 1A). However, in actin-stabilized Δend3 and sla1Δ118-511 cells, Ras2p localizes to punctate foci around the plasma membrane of the cell (Fig. 1A). To investigate whether the membrane-associated Ras2p was in a GTP-bound active form, we made use of a previously described assay (6). In this assay, the purified GST-bound Raf RBD is used to specifically pull down active Ras from cell extracts (as described in Materials and Methods). Active Ras2p could not be detected by this method in wild-type stationary-phase cells, but a significant amount was pulled down from a protein extract prepared from a Δend3 mutant culture grown under the same conditions (Fig. 1B). Active Ras2p was also pulled down from extracts prepared from sla1Δ118-511 cells by using this method (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Ras/cAMP pathway is hyperactivated in actin-stabilized cells. (A) Immunofluorescence was carried out to show colocalization of F-actin (red) with Ras2p (green) in wild-type, Δend3, and sla1Δ118-511 stationary-phase cells, as described in Materials and Methods. (B) To determine the state of Ras2p activity, GTP-bound Ras2p was detected in extracts prepared from wild-type and Δend3 stationary-phase cells by a pull-down method using purified GST-RafRBD, as described in Materials and Methods. (C) The activity of Ras2p was also investigated in vivo using immunofluorescence to show colocalization of F-actin (red) with active Ras2p (green). This was achieved by overlaying fixed wild-type and Δend3 stationary-phase cells with purified GST-RafRBD (see Materials and Methods) and utilizing anti-GST antibodies to detect RafRBD localization. Bar = 10 μm. (D) An assay to determine the cAMP levels in wild-type, Δend3, and sla1Δ118-511 stationary-phase cells was carried out in triplicate using a nonradioactive immunoassay (see Materials and Methods). Error bars represent standard deviations.

To confirm that Ras2p was activated in Δend3 cells in vivo, we performed an overlay experiment using the GST-RafRBD binding principle described in Materials and Methods. In wild-type cells, active Ras2p staining was diffuse, while in Δend3 cells a discrete localization around the cell periphery was observed (Fig. 1C). These data confirm that Ras2p is predominantly in the active state in actin-stabilized stationary-phase cells.

Hyperactivation of Ras2p should result in the elevation of cAMP. We therefore determined the cAMP levels in wild-type, Δend3, and sla1Δ118-511 stationary-phase cells. Wild-type cells contained about 200 fmol of cAMP per 107 cells. However, in cells lacking End3p and in sla1Δ11-511 mutant cells, there were 3.2- and 2.1-fold increases in the cAMP level, respectively, compared to that in wild-type cells (Fig. 1D). Thus, the activation of Ras2p in actin-stabilized stationary-phase cells is accompanied by an increase in cAMP.

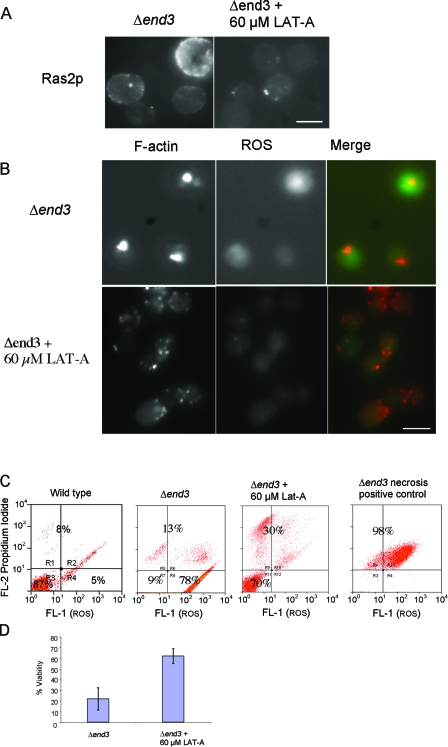

Actin dynamics modulate Ras2p activation and apoptosis.

We had previously observed that the addition of low levels of the actin monomer-sequestering drug LAT-A to cultures at the time of inoculation could inhibit the formation of actin aggregates in stationary-phase Δend3 cells (C. Gourlay, unpublished observations). To establish the lowest concentration of LAT-A which could prevent actin aggregation in Δend3 cells but allowed normal growth to occur, we examined the effects of concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 μM (data not shown). It was established that the optimal concentration that met these criteria was 60 μM (data not shown). We therefore investigated the effects of directly inhibiting actin aggregation by the addition of 60 μM LAT-A on Ras2p activation and apoptosis in Δend3 cells. Initially, we examined whether LAT-A addition was sufficient to prevent Ras2p activation in stationary-phase Δend3 cells (Fig. 2A). The pronounced cortical distribution of active Ras2p observed in Δend3 stationary-phase cells was greatly reduced in LAT-A-treated cells (Fig. 2B), which is in line with the hypothesis that actin stabilization leads directly to Ras2p activation. We next examined the effect of LAT-A treatment on the accumulation of ROS and the aggregation of F-actin in stationary-phase Δend3 cells (Fig. 2B and C). F-actin and ROS were visualized in fixed Δend3 cells that had either been treated or left untreated with LAT-A during growth (Fig. 2B). F-actin aggregates and high ROS levels, as indicated by intense 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence, were observed in stationary-phase Δend3 cells, as previously reported (13). However, in Δend3 cells treated with LAT-A, the cortical F-actin cytoskeleton appeared as punctate patches reminiscent of those in wild-type stationary-phase cells (Fig. 2B). The observed reduction of actin aggregation in LAT-A-treated Δend3 cells is suggestive of a more dynamic actin cytoskeleton. In addition to this observation, LAT-A-treated Δend3 cells displayed greatly reduced levels of ROS, as indicated by reduced levels of DCF staining (Fig. 2B). To verify that LAT-A addition could also prevent the apoptosis observed in Δend3 cells, we used flow cytometry to measure ROS levels and propidium iodide uptake in LAT-A-treated and untreated Δend3 cells (Fig. 2C) in combination with a viability assay on the same cultures (Fig. 2D). A positive control for necrotic cells (see Materials and Methods) was also included to allow the identification of true apoptotic cells (Fig. 2C). As shown in the representative histograms, Δend3 cells exhibited high levels of ROS and low propidium iodide uptake, which is suggestive of a predominantly apoptotic population (Fig. 2C). The addition of 60 μM LAT-A to Δend3 cell cultures prevented ROS accumulation, suggesting a shift to a nonapoptotic population. To verify that the inhibition of ROS accumulation upon LAT-A treatment results in reduced levels of cell death, we conducted viability assays under the same conditions (Fig. 2D). We found that the addition of 60 μM LAT-A to Δend3 cells resulted in an increase in viability, from 22% ± 10%, observed for Δend3 cells, to 62% ± 7% (Fig. 2D). These data argue strongly that F-actin stabilization can trigger Ras2p activation and apoptosis.

FIG. 2.

Actin stabilization directly activates Ras signaling and apoptosis. (A) The effect of the addition of 60 μM LAT-A to growth medium at the time of inoculation on F-actin organization and ROS accumulation in Δend3 cells was observed. The localization of Ras2p was also investigated in Δend3 cells grown to stationary phase with and without 60 μM LAT-A by using immunofluorescence. (B) F-actin was visualized by rhodamine-phalloidine staining and the presence of ROS was assessed by staining with H2DCF-DA in Δend3 cells, which were either untreated or treated with 60 μM LAT-A and allowed to grow to early stationary phase. Merged images of F-actin and ROS are also presented. Bar = 10 μm. (C) The effect of LAT-A treatment on cell death was investigated using flow cytometry to measure propidium iodide uptake and ROS accumulation in treated and untreated Δend3 cells. As a positive control to demarcate the necrotic cell fraction, Δend3 cells which had been heat treated at 80°C for 2 min were also stained. (D) A viability study was carried out with cells to assess the effects of the addition of 60 μM LAT-A to Δend3 cell cultures grown to stationary phase.

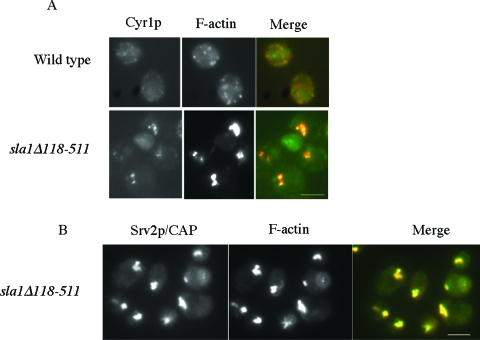

Components of the cAMP generation machinery localize to actin aggregates.

The effective transduction of an active Ras signal requires a complex of GTP-bound Ras, Srv2p/CAP, and adenylyl cyclase (Cyr1p). We considered that stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton may trigger constitutive Ras signaling by bringing Srv2p/CAP, Cyr1p, and Ras2p together in a complex. We examined the localization of Cyr1p and F-actin in wild-type and sla1Δ118-511 stationary-phase cells. The wild-type distribution of Cyr1p appeared to be punctate, and the protein did not localize with cortical F-actin patches (Fig. 3A). However, in sla1Δ118-511 cells, a proportion of Cyr1p staining was observed to localize with actin aggregates (Fig. 3A). The same localization of Cyr1p to actin aggregates was observed in Δend3 cells (data not shown). Srv2p/CAP also colocalized with actin aggregates in sla1Δ118-511 stationary-phase cells (Fig. 3B). No colocalization was observed between actin and Srv2p/CAP in wild-type stationary-phase cells, as previously described (13; data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Components of the cAMP generation machinery are sequestered in actin aggregates. Immunofluorescence was used to show colocalization of components of the cAMP generation module in wild-type and sla1Δ118-511 stationary-phase cells. F-actin (red) was colocalized with adenylate cyclase, Cyr1p (green) (A), and Srv2p/CAP (green) (B). Bar = 10 μm.

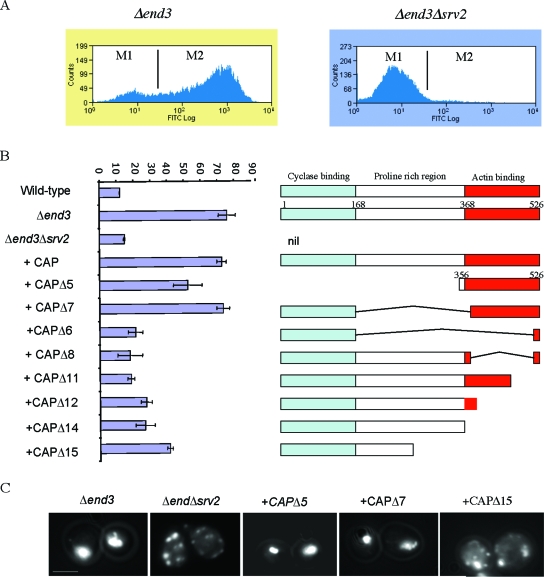

Srv2p/CAP is required for actin aggregation and ROS generation.

Srv2p/CAP is able bind to adenylyl cyclase via its N-terminal region (12) and to G-actin via its C terminus (10, 23). It also localizes to cortical F-actin structures via a central polyproline-containing region (11). It is therefore a good candidate to link Ras/cAMP signaling to cytoskeletal dynamics. We hypothesized that deletion of Srv2p/CAP from actin-stabilized Δend3 cells may reduce ROS accumulation by downregulating Ras/cAMP signaling. To test this hypothesis, we generated a Δend3 Δsrv2 double mutant strain. In agreement with our hypothesis, stationary-phase Δend3 Δsrv2 mutant cells failed to accumulate the high levels of ROS observed in Δend3 cells (Fig. 4A). In order to establish which region of Srv2p/CAP was required for ROS accumulation, we carried out a structure-function analysis. Plasmids expressing full-length Srv2p/CAP or various truncations of the protein were introduced into Δend3 Δsrv2 cells (Fig. 4B). The expression levels of replacement full-length Srv2p/CAP and all truncations were similar to those observed in wild-type cells on Western blots (data not shown). The replacement of full-length Srv2p/CAP in Δend3 Δsrv2 cells restored ROS production to the levels observed in the Δend3 mutant (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, expression of the C-terminal actin binding domain of Srv2p/CAP alone (CAPΔ5) was able to restore ROS accumulation, to approximately 70% of that observed in Δend3 cells. When both the C-terminal actin binding and N-terminal adenylyl cyclase binding domains were expressed (CAPΔ7), ROS levels were restored to the levels in Δend3 cells. This suggests that although the C-terminal domain conveys most of the Srv2p/CAP activity required for ROS production in Δend3 cells, the adenylyl cyclase-binding N-terminal region also contributes. These data also demonstrate that the central polyproline domain, which is required for F-actin localization, is not required. The importance of the C terminus in ROS production is highlighted by the fact that a truncated protein containing the N terminus and only the last 26 amino acids of the C terminus (CAPΔ6) failed to restore ROS accumulation. Similarly, the expression of CAPΔ8, CAPΔ11, CAPΔ12, and CAPΔ14, which harbor deletions in the C terminus, also failed to restore ROS levels. However, expression of these truncations did result in ROS levels which were consistently higher than that observed in wild-type cells. Additionally, the CAPΔ15 truncation restored ROS levels to 53% of that observed in Δend3 mutant cells. These results suggest a role for regions outside the C terminus of Srv2p/CAP in actin-stabilized induction of ROS production (Fig. 4B). F-actin staining was also carried out with Δend3 Δsrv2 stationary-phase cells expressing the various Srv2p/CAP truncations (Fig. 4C). Mutant Δend3 cells displayed the characteristic actin aggregation phenotype, which was rescued by the deletion of Srv2p/CAP (Fig. 4C). The reintroduction of full-length Srv2p/CAP restored actin aggregation, as did the expression of CAPΔ5 and CAPΔ7. The expression of all other truncations led to a phenotype similar to that of Δend3 Δsrv2 cells. To demonstrate this, the staining of F-actin in Δend3 Δsrv2 cells expressing CAPΔ15 is shown. It should be noted that the expression of CAPΔ5 in wild-type cells had no observable effect on F-actin staining or ROS production (data not shown). This suggests that the C-terminal region of Srv2p/CAP does not exhibit dominant functionality in wild-type cells, in agreement with previous studies (23).

FIG. 4.

Srv2p/CAP mediates actin aggregation and ROS formation in actin-stabilized cells. (A) ROS accumulation was assayed using H2DCF-DA in Δend3 and Δend3 Δsrv2 stationary-phase cells by flow cytometry (see Materials and Methods). The resultant data were plotted on histograms and divided into M1 and M2 regions, reflecting small and large ROS populations, respectively. (B) Similarly, ROS accumulation was assessed in triplicate in wild-type, Δend3, Δend3 Δsrv2, and Δend3Δsrv2 cells expressing either full-length Srv2/CAP or various truncations of Srv2/CAP (CAPΔ5-15). The percentages of cells appearing in the M2 region (large number of ROS cells) are presented. Error bars represent the standard errors obtained from triplicate experiments. (C) The F-actin architecture was visualized in Δend3 cells and in Δend3 Δsrv2 cells expressing various truncations of Srv2p/CAP by fluorescence microscopy using rhodamine-phalloidine as described previously. Bar = 10 μm.

Elevation of cAMP leads to actin-mediated apoptosis.

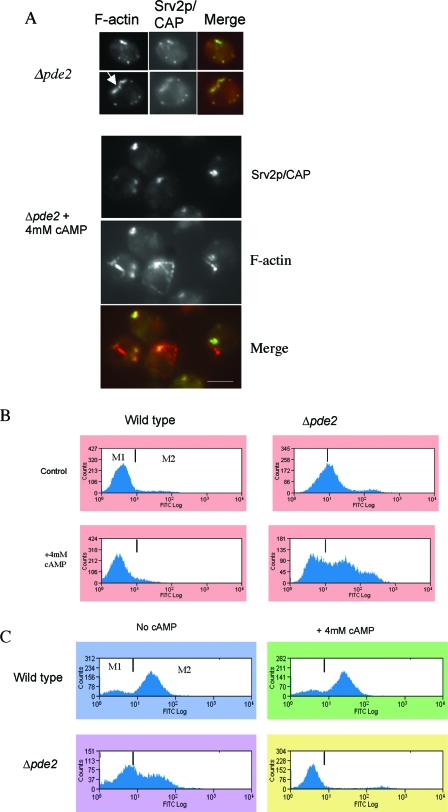

The overexpression of PDE2 can prevent apoptosis in actin-stabilized cells (13). We therefore asked whether the elevation of cAMP alone is sufficient to give rise to the actin and mitochondrial phenotypes observed in actin-stabilized cells. It has been reported that the addition of exogenous cAMP to cells lacking PDE2, at concentrations from 3 to 5 mM, leads to phenotypes similar to those observed for mutants exhibiting constitutive Ras signaling (7, 24). The same levels of cAMP have no observable effects on wild-type cells. We therefore grew wild-type and Δpde2 cells to stationary phase in the presence of 4 mM cAMP and observed the effects on actin organization, the MMP, and ROS accumulation. The addition of 4 mM cAMP caused no observable defects in actin organization in wild-type cells (data not shown). Stationary-phase cells lacking Pde2p displayed a largely wild-type F-actin arrangement, with numerous punctate, cortical actin patches to which Srv2p colocalized (Fig. 5A). However, approximately 50% of Δpde2 cells possessed abnormal, elongated F-actin structures, an example of which is indicated by an arrowhead in Fig. 5A. In contrast, the addition of 4 mM cAMP to cells lacking Pde2p resulted in profound alterations in the F-actin appearance (Fig. 5A). Both large cortical actin aggregates and aberrant long, thickened actin cable-like structures were observed (Fig. 5A). Srv2p/CAP, which is only found in cortical actin patches, localized to the F-actin aggregates but not to the thickened cables. These observations suggest that the addition of cAMP to Δpde2 cells leads to the stabilization of both actin patches and cables. Wild-type cells grown in the presence of cAMP also showed no increase in ROS accumulation (Fig. 5B). In contrast, Δpde2 cells displayed elevated ROS levels, which were further stimulated when cAMP was added (Fig. 5B). Wild-type cells showed no variation in MMP when grown in the presence of cAMP (Fig. 5C). However, cells in which PDE2 had been deleted exhibited a significant reduction in stationary-phase MMP compared to that in wild-type cells (Fig. 5C). This reduction was further compounded when cells were grown in the presence of exogenous cAMP (Fig. 5C). The addition of 4 mM AMP, which was used as a negative control, had no observable phenotypic effects on wild-type cells or cells lacking Pde2p (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

cAMP elevation results in actin aggregation and apoptosis. (A) Immunofluorescence microscopy was used to show colocalization of F-actin (red) and Srv2p/CAP (green) in cells lacking Pde2p, which had been grown to stationary phase under normal growth conditions or in the presence of 4 mM cAMP. Bar = 10 μm. Under the same conditions, ROS accumulation was assayed using H2DCF-DA (B) and MMP was measured using DiOC6 (C) by flow cytometry. Histograms of single representative experiments are shown.

cAMP-induced actin stabilization and ROS production are mediated through PKA.

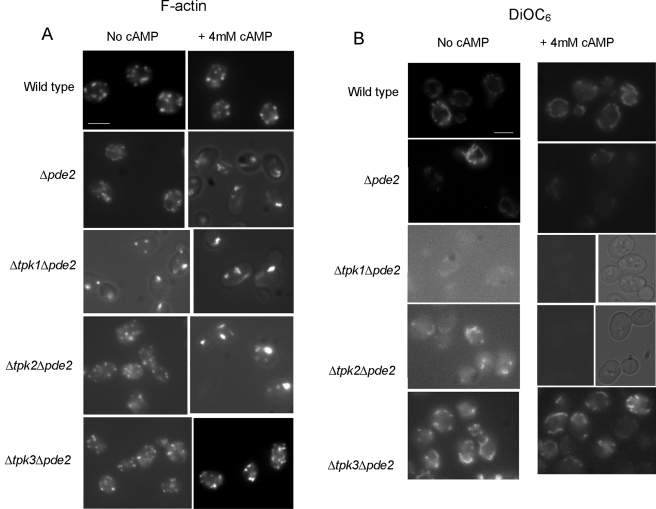

The target of cAMP is the regulatory kinase PKA, which has three potential catalytic subunits, encoded by TPK1-3. We therefore made double mutant strains lacking PDE2 and one of the three PKA subunits. We wanted to investigate whether the elevation of cAMP required the function of a single subunit to induce actin stabilization and apoptosis. We therefore deleted each subunit from a strain lacking Pde2p and subjected the mutants to cAMP elevation as described above (Fig. 6A). Wild-type cells grown to stationary phase with or without the addition of 4 mM cAMP exhibited normal punctate cortical actin staining. As described above, Δpde2 cells were observed to have relatively normal F-actin cytoskeletons, with a proportion of cells displaying aberrant elongated structures. The addition of 4 mM cAMP to Δpde2 cells caused a thickening of actin patches and cables, as described above. In cells lacking Pde2p, the loss of Tpk1p led to abnormal F-actin staining, even without the addition of exogenous cAMP (Fig. 6A). The addition of 4 mM cAMP to cells lacking both Pde2p and Tpk1p resulted in the enlargement of actin aggregates and further cable thickening (Fig. 6A). Cells deleted for Tpk2p and lacking Pde2p exhibited wild-type actin cytoskeletons under normal growth conditions but displayed actin stabilization when grown in the presence of additional cAMP (Fig. 6A). Strikingly, the loss of Tpk3p function in cells lacking Pde2p rendered cells unresponsive to the addition of cAMP, and F-actin organization in this mutant appeared similar to that in the wild type, with or without the addition of cAMP (Fig. 6A).

FIG.6.

cAMP elevation signals through the Tpk3p subunit of PKA to induce actin aggregation and apoptosis. Rhodamine-phalloidine staining was used to visualize F-actin (A) and MMP was assessed using DiOC6 staining (B) by fluorescence microscopy of wild-type, Δpde2, Δtpk1 Δpde2, Δtpk2 Δpde2, and Δtpk3 Δpde2 cells which had been grown to stationary phase in the presence or absence of 4 mM cAMP. (C) ROS accumulation was also assayed, using H2DCF-DA, by flow cytometry of wild-type, Δtpk1 Δpde2, Δtpk2 Δpde2, and Δtpk3 Δpde2 cells grown to stationary phase in the presence of 4 mM cAMP. Histograms of single representative experiments are shown. (D) We also assessed the effects of growing wild-type, Δpde2, Δtpk1 Δpde2, Δtpk2 Δpde2, and Δtpk3 Δpde2 cells to stationary phase in the presence of 4 mM cAMP on culture viability. Error bars represent standard deviations from triplicate experiments. (E) To investigate whether an elevation of the cAMP level resulted in the activation of Ras2p, the localization of Ras2p was assessed in Δpde2 cells which had been grown to stationary phase in the presence of 4 mM cAMP. F-actin architecture was also assessed in these cells by rhodamine-phalloidine staining, and a merged image is also presented. Bar = 10 μm.

We also measured the effects of cAMP elevation on MMP in these mutants by DiOC6 staining. Wild-type cells showed no difference in MMP when grown in the presence of cAMP (Fig. 6B). A reduced level of DiOC6 staining was observed in Δpde2 cells, which was further reduced in the presence of exogenous 4 mM cAMP. Strikingly, MMP was undetectable by DiOC6 staining in cells lacking both Pde2p and Tpk1p functions under both normal growth conditions and conditions in the presence of 4 mM cAMP (Fig. 6B). Cells lacking both Pde2p and Tpk2p functions also displayed a reduced MMP under normal growth conditions, and this was reduced further when cells were grown with 4 mM cAMP (Fig. 6B). In contrast, cells lacking Pde2p and Tpk3p were insensitive to cAMP addition and maintained their MMP (Fig. 6B). We then examined the effect of cAMP addition on ROS production in wild-type, Δpde2 Δtpk1, Δpde2 Δtpk2, and Δpde2 Δtpk3 cells (Fig. 6C). In wild-type cells, the addition of cAMP did not cause an increase in ROS, while cells lacking both Pde2p and Tpk1p exhibited high ROS levels (Fig. 6C). The presence of 4 mM cAMP also induced an increase in the ROS level in Δpde2 Δtpk2 cells compared to that in the wild type, but the level was lower than that observed for Δpde2 Δtpk1 cells. In line with the insensitivity of Δpde2 Δtpk3 cells to cAMP addition, the ROS level in this mutant strain appeared similar to that observed in wild-type cells (Fig. 6C). Since the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and increased ROS levels are indicators of apoptosis, we would expect reductions in culture viability to correlate with the above observations. The effect of cAMP addition on viability was therefore assessed (Fig. 6D). Wild-type cells grown in the presence of 4 mM cAMP showed a high level of viability (74% ± 3.5%). Cells lacking Pde2p grown under the same conditions had a marked reduction in culture viability (51% ± 6.4%). The largest reduction in viability was observed when cells lacking both Pde2p and Tpk1p were grown in the presence of 4 mM cAMP (32% ± 9.6%). Mutant Δpde2 Δtpk2 cells showed some resistance to cAMP addition, displaying a culture viability of 64% ± 7.5%. Cells lacking Pde2p and Tpk3p again appeared unresponsive to exogenous cAMP addition, showing wild-type levels of viability (80% ± 6.1%).

Our data demonstrate that the addition of exogenous cAMP can stabilize the F-actin cytoskeleton. We therefore wished to test whether cAMP elevation itself could lead to the localization of Ras2p to the plasma membrane in stationary-phase cells. To examine this possibility, we grew Δpde2 cells to stationary phase in the presence of 4 mM cAMP and observed both F-actin and Ras2p localization (Fig. 6E). Although stabilized F-actin aggregates were clearly observed under these conditions, Ras2p did not become localized to the plasma membrane (Fig. 6E).

Tpk3p is required to execute actin-mediated apoptosis in Δend3 cells.

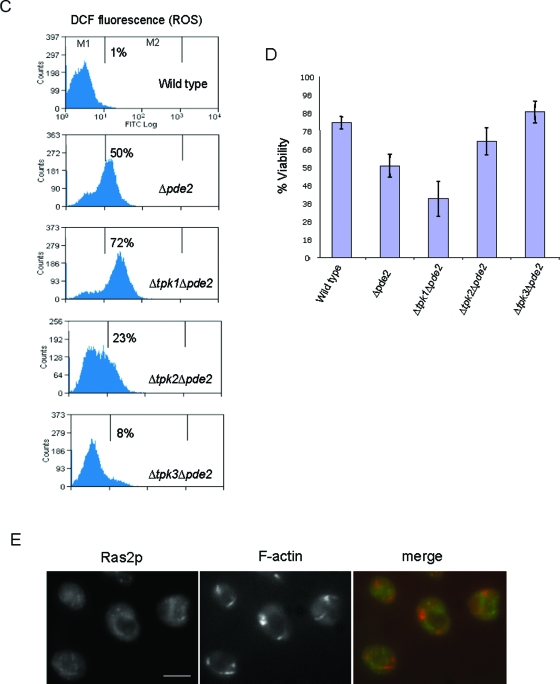

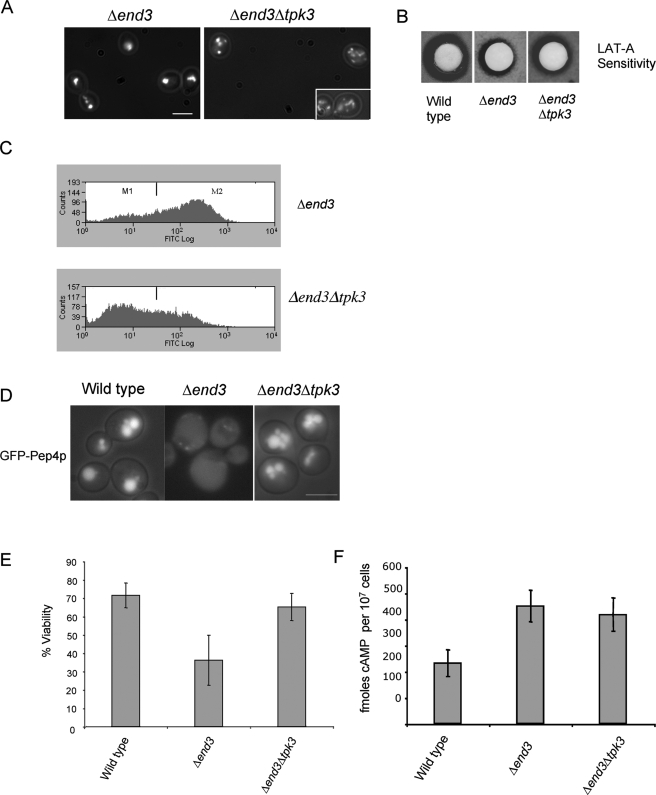

The addition of exogenous cAMP to Δpde2 cells gives rise to a similar phenotypic suite to that observed in actin-stabilized Δend3 cells. Since Tpk3p is required for the detrimental effects of cAMP elevation in Δpde2 cells, we investigated what effects deletion of TPK3 would have in Δend3 cells. To investigate this, a double mutant strain lacking both End3p and Tpk3p functions (Δend3 Δtpk3) was generated. Initially, F-actin organization was analyzed in these cells in the stationary phase of growth. The deletion of TPK3 in actin-stabilized Δend3 cells resulted in a significant reduction in the F-actin aggregation observed in cells lacking End3p (Fig. 7A). To confirm that the loss of Tpk3p function resulted in an increase in the dynamic state of the actin cytoskeleton, we carried out a LAT-A halo assay as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 7B). The clearance zone that arises in this assay is a reflection of how accessible the monomeric actin pool is to the sequestering activity of LAT-A and so acts as an indicator of how rapidly actin is being turned over in the cell. The reduction in sensitivity which Δend3 cells display, represented by a halo with a smaller diameter than that of the halo surrounding wild-type cells, occurs as a result of stabilized actin and decreased monomer turnover. As shown, cells lacking both END3 and TPK3 display a 5 mM LAT-A clearance halo with a diameter that is intermediate between those of the halos exhibited by wild-type and Δend3 cells (Fig. 7B). This confirms the previous observation that Tpk3p plays a role in the stabilization of actin and the formation of aggregates in stationary-phase Δend3 cells. We then wished to examine whether Tpk3p was required for actin-mediated apoptosis in Δend3 cells. In favor of this hypothesis, we observed a substantial reduction in ROS accumulation in stationary-phase Δend3 Δtpk3 cells compared to that in the Δend3 single mutant strain (Fig. 7C). It was recently described that an increase in vacuole membrane permeability is observed in apoptotic yeast cells (22). This can be monitored by visualizing the distribution of the vacuolar protease Pep4p, using a GFP fusion molecule (Fig. 7D). GFP-Pep4 localized exclusively to the vacuolar compartment in stationary-phase wild-type cells. However, in apoptotic cells lacking End3p, GFP-Pep4 was diffuse throughout the cell, indicating an increase in vacuole permeability (Fig. 7D). In line with the hypothesis that Tpk3p is required for apoptosis in Δend3 cells, the GFP-Pep4 distribution was constrained to the vacuole in Δend3 Δtpk3 cells (Fig. 7D). Thus, Tpk3p plays a significant role in actin aggregation and ROS generation in Δend3 cells. The loss of Tpk3p activity in Δend3 cells was also sufficient to restore culture viability (Fig. 7E). We also examined whether Δend3 Δtpk3 cells displayed reduced levels of cAMP compared to those in Δend3 cells (Fig. 7F). We found that although a small decrease in cAMP level was observed in Δend3 Δtpk3 cells (419 ± 63 fmol cAMP per 107 cells) compared to that in Δend3 cells (452 ± 60 fmol cAMP per 107 cells), the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 7F), and the level remained elevated compared to that observed in wild-type cells (233 ± 50 fmol cAMP per 107 cells). These data strengthen the argument that a pathway leading from actin stabilization leads to the activation of Ras signaling and apoptosis mediated by PKA, primarily through the Tpk3p subunit.

FIG. 7.

TPK3 is required for actin aggregation and ROS accumulation in Δend3 cells. F-actin staining was visualized using rhodamine-phalloidin staining (A), and ROS accumulation was assayed using H2DCF-DA for flow cytometry (C) of stationary-phase Δend3 and Δend Δtpk3 cells. (B) To further assess the effect of the loss of Tpk3p activity on actin dynamics in Δend3 cells, a LAT-A halo sensitivity assay was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. The role of Tpk3p in apoptosis was investigated by observing the localization of GFP-Pep4 (D) and by conducting a viability assay (E) with wild-type, Δend3, and Δend Δtpk3 cells. (F) To determine whether the loss of Tpk3p function led to reduced Ras/cAMP signaling activity, the levels of cAMP were determined in wild-type, Δend3, and Δend Δtpk3 cells. Bar = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

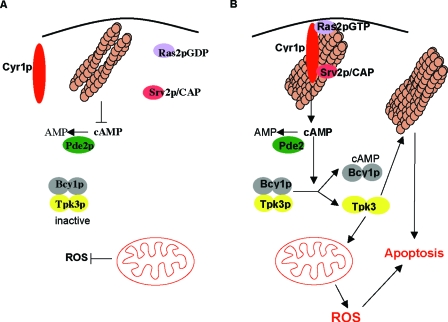

The coordination of cell growth and stress responses with environmental conditions is central to survival. In fungi, the regulation of Ras/cAMP/PKA signaling is integral to the management of metabolic activity in response to external cues (33). The remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton is also an important event in the response to environmental change. The data we present here demonstrate for the first time that actin regulation and cAMP signaling are linked in a pathway which regulates mitochondrial function, the accumulation of ROS, and apoptosis in yeast (Fig. 8). The cortical patch proteins Sla1p and End3p exist in a complex which regulates the dynamic nature of cortical actin patches (1, 3, 31). In cells lacking these proteins, actin dynamics are reduced, and aggregated F-actin structures arise (1, 3). This aggregation becomes particularly pronounced when actin-stabilized Δend3 and sla1Δ118-511 cells enter the stationary phase of growth (13). Here we show that Ras signaling becomes hyperactivated in actin-stabilized stationary-phase Δend3 and sla1Δ118-511 cells. This activation has severe consequences for the cell, as the resultant elevation of cAMP results in elevated ROS levels and apoptosis. Our results are in line with those of other studies showing that the elevation of ROS levels in cells with constitutively active Ras signaling (15, 17) results in a life span reduction (15). The regulation of Ras signaling has also been shown to regulate apoptosis in the pathogenic yeast C. albicans, suggesting a conserved role for this pathway among fungi (25).

FIG. 8.

Actin stabilization triggers constitutive Ras/cAMP/PKA signaling and apoptosis in stationary-phase S. cerevisiae cells. In wild-type cells, components of the Ras pathway are not found in association with F-actin during stationary phase. A reduction in Ras activity leads to a fall in cAMP, which results in PKA inactivation and the downregulation of signaling (A). (B) In actin-stabilized cells, components of the cAMP generation machinery, adenylyl cyclase (Cyr1p) and Srv2p, are found in association with large aggregates of actin during stationary phase and Ras2p is found to be constitutively active. This hyperactive Ras signaling state gives rise to the elevation of cAMP and the activation of PKA. This cascade of events triggers the elevation of ROS derived from the mitochondria and apoptosis. The PKA subunit Tpk3p is primarily responsible for the induction of apoptosis in response to actin-mediated hyperactivation of the Ras signaling pathway. It is likely that Tpk3p acts directly on both F-actin regulatory proteins and alters the enzymatic content of mitochondria to elicit this response. The combination of aggregated actin and constitutive Ras signaling may act together to establish conditions which lead to apoptotic cell death.

The effective transduction of Ras signaling through adenylyl cyclase requires Srv2p/CAP. Srv2p/CAP exhibits both adenylyl cyclase-activating and actin binding and regulatory functions. While a role for Srv2p/CAP in coupling Ras pathway activity to remodeling of actin has been an attractive hypothesis for many years, no clear evidence for this role exists. Here we have shown that both the G-actin-binding C terminus and the cyclase-binding N terminus of Srv2p/CAP are required for maximal ROS accumulation in actin-stabilized Δend3 cells. ROS accumulation appears to arise as a consequence of unregulated cAMP signaling in Δend3 cells. Surprisingly, the expression of the N terminus of Srv2p/CAP, which is capable of transducing the active Ras signal, was found to play a lesser role in ROS accumulation and actin aggregation than that of the G-actin-binding C-terminal domain. The C terminus alone was sufficient to induce actin aggregates and high levels of ROS in actin-stabilized cells. These data provide the first evidence that Srv2p/CAP can link the regulation of actin to the Ras signaling pathway. In wild-type cells, it may be the case that actin remodeling upon entry into stationary phase ensures that components of the Ras signaling pathway are separated, resulting in downregulation of the pathway. In actin-stabilized cells, actin aggregates may be formed as a result of Srv2p/CAP-induced “seeds,” which bring together Cyr1p and Ras2p in an inappropriate signaling module (Fig. 8). A proportion of the Cyr1p detectable by immunofluorescence was found in association with actin aggregates, as was Srv2p/CAP. Since active Ras2p localizes around the entire cell in punctate formations, aggregations containing Cyr1p and Srv2p/CAP may exhibit unregulated cAMP signaling. It is likely that cAMP elevation is a major contributory factor in the toxicity observed in actin-stabilized cells. In support of this, the overexpression of PDE2, whose product hydrolyzes cAMP to AMP, in actin-stabilized cells resulted in reduced ROS levels and the rescue of viability (13). We were able to demonstrate the effects of cAMP elevation directly by the addition of exogenous cAMP to a responsive Δpde2 strain. The elevation of cAMP had a profound effect on actin organization in cells grown to stationary phase. These cells exhibited thickened actin cables and aggregates of cortical actin. In addition, a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and the accumulation of ROS were observed. The similarity of these phenotypes to those displayed by Δend3 and sla1Δ118-511 cells is good evidence that hyperactivity of the Ras pathway is a major factor in yeast actin-mediated apoptosis. It should be noted, however, that actin-stabilized Δend3 and sla1Δ118-511 cells showed greater elevations of ROS than that induced by cAMP addition alone and did not exhibit thickened actin cables. It may be the case that cAMP elevation has a general role in stabilization of the actin cytoskeleton and has the effect of exacerbating existing structures. Cortical F-actin patches are enlarged in Δend3 and sla1Δ118-511 cells during exponential growth, and this may provide the basis for the larger actin aggregates seen in stationary-phase cells. The presence of large aggregates correlates with higher levels of ROS and thus is more toxic to the cell.

The reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential and increase in ROS level when cAMP levels are elevated occur as a result of PKA activity. These effects are mediated primarily through the Tpk3p subunit, although Tpk2p also appears to contribute. Interestingly, the deletion of TPK1 rendered Δpde2 cells hypersensitive to cAMP addition, implicating Tpk1p in a protective role against apoptosis in S. cerevisiae. The deletion of TPK3 from cells lacking Pde2p function rendered the strain insensitive to cAMP addition in terms of MMP depolarization, ROS accumulation, and actin aggregation. Additionally, actin-stabilized Δend3 cells displayed greatly reduced ROS production and actin aggregation in stationary phase when Tpk3p function was absent. ROS accumulation occurs in actin-stabilized cells as a result of electron transport chain activity, as their production could be prevented by the complex III inhibitor antimycin A (13). This therefore suggests that actin stabilization leads to mitochondrial dysfunction. Recent research has shown that Tpk3p is the PKA subunit primarily involved in the regulation of the mitochondrial enzyme content (4). We have shown that actin stabilization leads to the Tpk3p-dependent production of ROS. It is quite likely that a Tpk3p-induced imbalance of electron transport chain components contributes to the accumulation of toxic radicals in actin-stabilized cells. Our evidence also suggests that Tpk3p may have cytoskeletal targets, as its loss inhibited actin aggregation in Δend3 cells. Several cytoskeletal proteins contain PKA consensus sites, including Bbc1p and Bzz1p, which both regulate actin dynamics through interactions with the S. cerevisiae WASP homologue Las17p and with Sla1p (28, 30). The elevation of intracellular cAMP levels by exogenous addition to cells lacking Pde2p was also able to stabilize F-actin structures, leading to thickened cortical patches and cables. This effect was also Tpk3p dependent, providing further evidence that the yeast actin cytoskeleton can be regulated by protein kinase A activity. An attractive hypothesis is that reduced actin dynamics lead to Ras activation and consequential cAMP elevation, which stabilizes F-actin structures further and causes the establishment of a positive feedback loop which climaxes in apoptosis. However, cAMP levels were not significantly reduced in Δend3 Δtpk3 cells, which is not consistent with the presence of such a positive feedback loop. In addition, the addition of exogenous cAMP to Δpde2 cells did not lead to observable Ras2p localization to the plasma membrane. These data argue that a more linear pathway exists (Fig. 8), in which cAMP-induced actin stabilization may contribute to the execution of apoptosis, as opposed to triggering further Ras signaling.

The data we have presented provide clear evidence that actin regulation plays an important role in the regulation of Ras/cAMP/PKA signaling and apoptosis during stationary phase in S. cerevisiae. The actin cytoskeleton plays a pivotal role in many eukaryotic signaling pathways, and thus an alteration in its regulation will likely have a significant impact on a cell's efficiency at responding to a changing environment. This and the discovery that actin dynamics are linked to apoptosis regulation promote the hypothesis that the actin cytoskeleton can be used as a biosensor of cellular well-being and a mechanism by which aged cells can be pruned from a mixed population.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Field, J. S. Moghraby, and A. Robertson for critically reading the manuscript, T. Kataoka (Kobe University School of Medicine) and D. Drubin (University of California at Berkeley) for antibodies, and J. Field (University of Pennsylvania) and D. Goldfarb (University of Rochester) for very generous plasmid donations.

This work was sponsored by a Medical Research Council (MRC) senior research fellowship to K.R.A. (G117/394).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayscough, K. R., J. J. Eby, T. Lila, H. Dewar, K. G. Kozminski, and D. G. Drubin. 1999. Sla1p is a functionally modular component of the yeast cortical actin cytoskeleton required for correct localization of both Rho1p-GTPase and Sla2p, a protein with talin homology. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:1061-1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balaban, R. S., S. Nemoto, and T. Finkel. 2005. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 120:483-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benedetti, H., S. Raths, F. Crausaz, and H. Riezman. 1994. The END3 gene encodes a protein that is required for the internalization step of endocytosis and for actin cytoskeleton organization in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 5:1023-1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevtzoff, C., J. Vallortigara, N. Averet, M. Rigoulet, and A. Devin. 2005. The yeast cAMP protein kinase Tpk3p is involved in the regulation of mitochondrial enzymatic content during growth. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1706:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi, J., H. D. Rees, S. T. Weintraub, A. I. Levey, L. S. Chin, and L. Li. 2005. Oxidative modifications and aggregation of Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase associated with Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 280:11648-11655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombo, S., D. Ronchetti, J. M. Thevelein, J. Winderickx, and E. Martegani. 2004. Activation state of the Ras2 protein and glucose-induced signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 279:46715-46722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dejean, L., B. Beauvoit, A. P. Alonso, O. Bunoust, B. Guerin, and M. Rigoulet. 2002. cAMP-induced modulation of the growth yield of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during respiratory and respiro-fermentative metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1554:159-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dejean, L., B. Beauvoit, O. Bunoust, B. Guerin, and M. Rigoulet. 2002. Activation of Ras cascade increases the mitochondrial enzyme content of respiratory competent yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293:1383-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkel, T. 2005. Opinion: radical medicine: treating aging to cure disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 6:971-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman, N. L., Z. Chen, J. Horenstein, A. Weber, and J. Field. 1995. An actin monomer binding activity localizes to the carboxyl-terminal half of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyclase-associated protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270:5680-5685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman, N. L., T. Lila, K. A. Mintzer, Z. Chen, A. J. Pahk, R. Ren, D. G. Drubin, and J. Field. 1996. A conserved proline-rich region of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyclase-associated protein binds SH3 domains and modulates cytoskeletal localization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:548-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerst, J. E., K. Ferguson, A. Vojtek, M. Wigler, and J. Field. 1991. CAP is a bifunctional component of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae adenylyl cyclase complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:1248-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gourlay, C. W., and K. R. Ayscough. 2005. Identification of an upstream regulatory pathway controlling actin-mediated apoptosis in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 118:2119-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gourlay, C. W., L. N. Carpp, P. Timpson, S. J. Winder, and K. R. Ayscough. 2004. A role for the actin cytoskeleton in cell death and aging in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 164:803-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeren, G., S. Jarolim, P. Laun, M. Rinnerthaler, K. Stolze, G. G. Perrone, S. D. Kohlwein, H. Nohl, I. W. Dawes, and M. Breitenbach. 2004. The role of respiration, reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress in mother cell-specific aging of yeast strains defective in the RAS signalling pathway. FEMS Yeast Res. 5:157-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herker, E., H. Jungwirth, K. A. Lehmann, C. Maldener, K. U. Frohlich, S. Wissing, S. Buttner, M. Fehr, S. Sigrist, and F. Madeo. 2004. Chronological aging leads to apoptosis in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 164:501-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hlavata, L., H. Aguilaniu, A. Pichova, and T. Nystrom. 2003. The oncogenic RAS2(val19) mutation locks respiration, independently of PKA, in a mode prone to generate ROS. EMBO J. 22:3337-3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laun, P., A. Pichova, F. Madeo, J. Fuchs, A. Ellinger, S. Kohlwein, I. Dawes, K. U. Frohlich, and M. Breitenbach. 2001. Aged mother cells of Saccharomyces cerevisiae show markers of oxidative stress and apoptosis. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1166-1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longo, V. D. 2004. Ras: the other pro-aging pathway. Sci. Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004:pe36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longo V. D., J. Mitteldorf, and V. P. Skulachev. 2005. Opinion: programmed and altruistic aging. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6:866-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason, D. A., N. Shulga, S. Undavai, E. Ferrando-May, M. F. Rexach, and D. S. Goldfarb. 2005. Increased nuclear envelope permeability and Pep4p-dependent degradation of nucleoporins during hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death. FEMS Yeast Res. 5:1237-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattila, P. K., O. Quintero-Monzon, J. Kugler, J. B. Moseley, S. C. Almo, P. Lappalainen, and B. L. Goode. 2004. A high-affinity interaction with ADP-actin monomers underlies the mechanism and in vivo function of Srv2/cyclase-associated protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:5158-5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitsuzawa, H. 1993. Responsiveness to exogenous cAMP of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain conferred by naturally occurring alleles of PDE1 and PDE2. Genetics 135:321-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips, A. J., J. D. Crowe, and M. Ramsdale. 2006. Ras pathway signaling accelerates programmed cell death in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:726-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rego, A. C., and C. R. Oliveira. 2003. Mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species in excitotoxicity and apoptosis: implications for the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem. Res. 28:1563-1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robertson, L. S., H. C. Causton, R. A. Young, and G. R. Fink. 2000. The yeast A kinases differentially regulate iron uptake and respiratory function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5984-5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodal, A. A., A. L. Manning, B. L. Goode, and D. G. Drubin. 2003. Negative regulation of yeast WASp by two SH3 domain-containing proteins. Curr. Biol. 13:1000-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serrano, M., A. W. Lin, M. E. McCurrach, D. Beach, and S. W. Lowe. 1997. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 88:593-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soulard, A., T. Lechler, V. Spiridonov, A. Shevchenko, R. Li, and B. Winsor. 2002. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Bzz1p is implicated with type I myosins in actin patch polarization and is able to recruit actin-polymerizing machinery in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7889-7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang, H. Y., J. Xu, and M. Cai. 2000. Pan1p, End3p, and S1a1p, three yeast proteins required for normal cortical actin cytoskeleton organization, associate with each other and play essential roles in cell wall morphogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:12-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thevelein, J. M. 1992. The RAS-adenylyl cyclase pathway and cell cycle control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 62:109-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thevelein, J. M., and J. H. de Winde. 1999. Novel sensing mechanisms and targets for the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 33:904-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thevelein, J. M., R. Gelade, I. Holsbeeks, O. Lagatie, Y. Popova, F. Rolland, F. Stolz, S. Van de Velde, P. Van Dijck, P. Vandormael, A. Van Nuland, K. Van Roey, G. Van Zeebroeck, and B. Yan. 2005. Nutrient sensing systems for rapid activation of the protein kinase A pathway in yeast. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:253-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toda, T., I. Uno, T. Ishikawa, S. Powers, T. Kataoka, D. Broek, S. Cameron, J. Broach, K. Matsumoto, and M. Wigler. 1985. In yeast, RAS proteins are controlling elements of adenylate cyclase. Cell 40:27-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]