Abstract

A striking characteristic of a Rab protein is its steady-state localization to the cytosolic surface of a particular subcellular membrane. In this study, we have undertaken a combined bioinformatic and experimental approach to examine the evolutionary conservation of Rab protein localization. A comprehensive primary sequence classification shows that 10 out of the 11 Rab proteins identified in the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) genome can be grouped within a major subclass, each comprising multiple Rab orthologs from diverse species. We compared the locations of individual yeast Rab proteins with their localizations following ectopic expression in mammalian cells. Our results suggest that green fluorescent protein-tagged Rab proteins maintain localizations across large evolutionary distances and that the major known player in the Rab localization pathway, mammalian Rab-GDI, is able to function in yeast. These findings enable us to provide insight into novel gene functions and classify the uncharacterized Rab proteins Ypt10p (YBR264C) as being involved in endocytic function and Ypt11p (YNL304W) as being localized to the endoplasmic reticulum, where we demonstrate it is required for organelle inheritance.

All eukaryotic cells are compartmentalized into distinct membrane-bound organelles and require tightly regulated transport of proteins and lipids between these compartments. Members of the Rab family of small GTPases are major regulators of protein and lipid traffic in the secretory and endocytic pathways (46, 65). The action of Rab proteins in membrane transport was discovered with the identification of the SEC4 and YPT1 genes in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)(51, 52) and related proteins, termed Rab proteins, from mammals (10). Rab proteins comprise the most numerous subfamily of the Ras superfamily, and many are functionally uncharacterized. It is not clear whether Rab proteins regulate events that take place in the donor compartment, the vesicle or transport carrier, the acceptor compartment, or multiple locations. Also not known is whether a function(s) can be described for Rab proteins in general or whether this must be considered on a case-by-case basis. However, it is clear that Rab proteins are essential for eukaryotic cells and absolutely required for the function of all organelles connected by SNARE-mediated membrane traffic.

With the completion of eukaryotic genome sequencing projects, there have been efforts to catalog the numbers of GTPase superfamily proteins. Membrane traffic in higher eukaryotes connects multiple compartments, and one reflection of this complexity may be the finding that humans have at least 60 different Rab family members (24, 55, 57). Other eukaryotes have fewer Rab proteins; Caenorhabditis elegans has 29 family members, Drosophila melanogaster has 26 members, and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has 11 members. As a model system, the 11 Rab proteins of the single-celled eukaryotic microbe S. cerevisiae can be considered the most minimal “membrome” (24), as other single-celled eukaryotes utilized as model systems contain a numerically larger set of Rab-encoding genes (35, 49).

A distinctive feature of the Rab protein is its steady-state localization to the cytosolic surface of a particular endomembrane. Each Rab protein has a unique subcellular membrane distribution mediated in part by COOH-terminal hypervariable sequences that lie just prior to the site of geranylgeranylation (9). Rab proteins divide their residence between the cytosol and their target membrane(s), and currently there is widespread support for a model suggesting that a critical step of Rab protein function is its recruitment from the cytosol to a particular membrane (1, 45). An alternative view is that the specific membrane localization of Rab proteins might be a readout of the activity of that organelle. In this scenario, the membrane localization is not a prerequisite for spatially restricted functionality but reflects an emergent property of the set of Rab-interacting proteins. If specific membrane localization is critical to the functions of Rab proteins, it might be a reasonable conjecture to assume that the mechanisms by which the specific localizations are achieved are universally shared among eukaryotes. This impression has been suggested by several instances where conserved Rab proteins have been demonstrated to localize or function between eukaryotes (see references 52 and 54 for details), but the notion has not been systematically examined on a genome-wide basis. Since Rab proteins are well conserved evolutionarily, S. cerevisiae has been extensively used as a model system for the determination of their specific functions, and much is known about many of the yeast Rab proteins.

In this study, we have made use of the existing knowledge regarding the function and location of characterized yeast Rab proteins to systematically examine (i) the influence of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag on Rab protein function, (ii) the hypothesis that the process of Rab membrane localization and recruitment is evolutionary conserved, and (iii) whether Rab localization in animal cells can shed more light on the identity of the organelle on which a Rab protein resides and the other organelles it directly communicates with via membrane traffic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression of yeast Rabs.

Yeast Rabs (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) under the control of the endogenous promoter and terminator were tagged with yeast-enhanced GFP (GenBank accession number U73901) at the open reading frame (ORF) 5′ terminus by PCR and cloned into either centromeric single-copy or integrating plasmids. Constructs were expressed at wild-type levels either in haploid cells as the only source of the Rab protein or in homozygous diploid cells where both copies were disrupted. The exceptions to the use of endogenous promoters were the Rab proteins Ypt10p and Ypt11p, which could barely be detected at endogenous levels, and the genes encoding these proteinswere typically expressed under the control of PYOP1 (8). Diploids were isolated on selective medium and subsequently sporulated at 23°C. Functionality was tested either by determining the ability of the tagged protein to act as the only cellular source of an essential gene to rescue a temperature-sensitive allele (Ypt31p/Ypt32p) or by observing the rescue of the mutant phenotype (Ypt7p, Ypt6p, and Ypt51p). YPT10 and GFP-YPT10 constructs under the control of Cu2+ were created using the CUP1-1/YHR053C promoter, consisting of 330 bases from the start of CUP1, and the endogenous YPT10 3′ region. The localization was monitored in haploid and diploid yeast cells (Novick laboratory or SC288C strain background); see Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material for yeast genotypes and plasmid constructs, respectively. Strains containing Sec61p-GFP and Spa2-GFP were constructed with the PCR-based integration system (37). Yeasts were grown to log phase in sucrose-dextrose medium supplemented with amino acids as required at 25°C. GFP-Sec4p, GFP-Ypt31p, and GFP-Ypt32p were also cotransformed with a red fluorescence protein (RFP)-tagged nuclear protein to monitor the state of the nucleus during budding. Hoechst 33258 stain was used at 0.5 g/ml and incubated with the growing yeast in minimal media for 5 min followed by washing with growth media before mounting.

Transfection into mammalian cells.

HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were maintained in alpha minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin and passaged twice weekly. BHK cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin and passaged twice weekly.

HeLa and BHK cells were transfected either with an Effectene transfection kit (QIAGEN) or with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturers' protocols. For transfection, cells were grown on 12-mm no. 1 coverslips in 24-well plates for approximately 24 h and transfected with 0.8 to 1 μg DNA. Transfections were typically allowed to proceed for 5 to 12 h before fixation and analysis.

Fluorescence microscopy procedures.

For live-cell microscopy of GFP-expressing yeast cells, the cells were grown to log phase, 2-μl aliquots were removed, and the cells were placed onto microscope slides under a no. 1 coverslip and observed immediately. Images were captured using a Nikon E600 microscope with a 60× objective (numerical aperture [NA], 1.4) and 2× Optivar or a 100× objective and 1× Optivar and an RT monochrome spot camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI) driven by QED Image (QED Imaging, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) or a Sensicam EM camera (Cooke Instruments, Inc.) driven with IPLab (Scanalytics). A Nikon remote focus accessory was used to capture stacks (0.2-μm slice size for yeast, 0.25 μm for mammalian cells) for deconvolution. Three-dimensional blind deconvolution was performed with AutoDeblur, version 9.1 (AutoQuant Imaging, Inc., Watervliet, NY). Stacks were deconvolved with 40 iterations using a medium- or low-noise correction level at the highest quality setting. All two-color images were first deconvolved in monochrome and then colored after deconvolution. Figures were made in Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). For wide-field microscopy of mammalian cells, cells were viewed on a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope using a 60× Plan Apo objective (NA, 1.4). Confocal microscopy was performed using an Olympus FluoView confocal station. Alexa 488 was excited with the 488-nm line of an argon laser, and Alexa 568 was excited with the 568-nm line of a krypton laser. Cells were viewed with a 60× Plan Apo objective lens (NA, 1.4), and images were captured with FluoView software (Olympus, Melville, NY). Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) inheritance assays were performed with an Olympus BX50 fluorescence microscope (100× objective; NA, 1.35) and TILLvisION software (TILL Photonics, Martinsried, Germany).

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy.

Yeast cells in early log phase were immediately fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min and fix replaced for 1 h. Cells were resuspended in spheroplasting buffer (100 mM KPi, pH 7.5, 1.2 M sorbitol), and 40 μg/ml Zymolase 20T was added. Cells were spheroplasted for 40 min at 37°C and allowed to settle onto polylysine-coated glass slides. Cells were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 and blocked in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-0.1% bovine serum albumin. The secondary antibodies used were Alexa 568-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Molecular Probes). The yeast endoplasmic reticulum was identified by using a monoclonal antibody against Pdi1p (EnCor Biotechnology). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (5 μg/ml), and cells were mounted in ProLong Gold (Molecular Probes).

The preparation of HeLa cells for immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (63). Briefly, cells were either fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min, quenched with 50 mM NH4Cl-PBS, and permeabilized for 5 min with 0.1% Triton X-100-PBS or fixed and permeabilized in cold methanol for 5 min. After blocking in 10% goat serum, cells were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies for 30 min each and mounted in Mowiol. The secondary antibodies used were Alexa 568-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes).

Antibodies and colocalization studies.

Early endosomes were localized using a monoclonal antibody directed against early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1) (Transduction Laboratories), late endosomes were localized using a monoclonal antibody directed against cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate receptor (Affinity BioReagents), lysosomes were localized using a monoclonal antibody directed against LAMP-1 (University of Iowa Hybridoma Bank), Golgi membranes were localized using a monoclonal antibody directed against the Golgi matrix protein GM130 (Transduction Laboratories), the trans-Golgi network was localized using a monoclonal antibody directed against TGN38 (Transduction Laboratories), and the endoplasmic reticulum was localized using monoclonal antibodies directed against protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) (Transduction Laboratories) or using ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX (Molecular Probes) at a concentration of 500 nM for 30 min at 37°C. The ER-Golgi intermediate compartment was localized using monoclonal antibodies against the KDEL receptor (Stressgen). To identify recycling endosomes, transferrin uptake assays were performed using Alexa 594-labeled human transferrin (kindly provided by Colin Parrish, Cornell University). HeLa cells were serum starved for 30 min, incubated with 50 μg/ml Alexa 594 transferrin for 20 min at 4°C, washed, and transferred to 37°C for 15 min before fixation.

Monoclonal anti-Rab 11 antibody was obtained from BD Transduction Labs. Cells were stimulated with the phorbol ester phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (LC Laboratories) at a concentration of 0.1 μM for 30 min at 37°C. To label the actin cytoskeleton, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and then incubated with tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-phalloidin (Sigma) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml for 10 min at room temperature.

For the quinacrine uptake assay, yeast cells in early log phase were harvested and resuspended in 500 μl yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YEPD)-PO4, pH 7.6, with 2 mM quinacrine dihydrochloride and incubated for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed twice with YEPD-PO4, pH 7.6, and viewed immediately with a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter set. To label vacuolar membranes, a 500-μl volume of cells grown to early log phase was incubated with 12 μg/ml FM4-64 (Molecular Probes) for 15 min. The cells were then washed twice with fresh medium, resuspended in 5 ml of YEPD, and incubated for 45 min with shaking. To visualize, 1 μl of cells was gently harvested by centrifugation, mounted for microscopy, and visualized with a rhodamine filter set.

RESULTS

In silico analysis.

Rab GTPases are numerically the largest subfamily of the Ras superfamily in S. cerevisiae, and complete genomic sequencing has revealed that this general observation can be extended to all eukaryotic organisms examined to date. To obtain a reference point for the 11 Rab paralogs of yeast (see the supplemental material) with other Rab sequences present in open access databases, we performed a phylogenetic analysis of all Rab protein sequences. Each sequence is represented as a single point provided by a principal components analysis of a numerically encoded relationship matrix derived from the alignment file (Fig. 1A) (11). The plot is two-dimensional, with the x and y axes representing the second and third principal components, respectively, of a numerical matrix derived from the alignment file. Each yeast Rab protein sequence can then be visually represented relative to the global Rab sequence space of all other known Rab sequences (Fig. 1B). On the plot representing the entire Rab sequence space, many of the data points appear to group together. The application of a clustering algorithm identified 10 major groups or subclasses of Rab proteins to which we have applied names corresponding to the most well-characterized member of each group. Each subclass contains orthologs from different species, while paralogs within a species are found distributed both within the major groups as functionally redundant isoforms and between groups. Rab sequences that do not fall into a major group can be thought of as more divergent sequences that may have evolved to provide specialized functions in differentiated cells of higher eukaryotes or for unusual organelles, such as the rhoptries of Toxoplasma gondii, which are unique to single-celled eukaryotes. Such sequences are particularly apparent in the top right-hand section of the plot (x > 0.02, y > 0.02). Rab sequences in this region may regulate exocytic function, as the area is also bounded by subclasses of sequence groups that include Rab3 and Rab8 (11). This analysis might suggest that these outliers may have a common involvement in biosynthetic or exocytic trafficking processes, whether constitutive or regulated. Interestingly, the yeast Rab protein of unknown function, Ypt11p, was observed to cluster with other Rabs of exocytic function and this is also suggested by its localization and functional analysis (see below).

FIG. 1.

Global view of Rab sequence space with two-dimensional principal components analysis. (A) The x and y axes represent the values of the second and third principal components, respectively. The analysis was performed on a database containing 560 individually checked and unique Rab sequences, including each Rab protein identified in S. cerevisiae. Automatic clustering with the Clusterdata function in Matlab was performed to identify major groupings in the data. This analysis identified 10 groups which are color coded and named according to a representative mammalian member of the group. (B) The position of each Rab protein present in the S. cerevisiae genome is indicated in relation to the global Rab sequence space. For a list of the Rab proteins in yeast and accession numbers, see the supplemental material.

The entire complement of Rab protein sequences in S. cerevisiae can be grouped within 6 of the 10 major subclasses of Rabs identified in Fig. 1A, with one exception, Ypt10p, which lies just outside the Rab5 group adjacent to mammalian Rab20 sequences (Fig. 1B). In this respect, S. cerevisiae can be considered a “streamlined” model eukaryote that possesses a minimal organelle set common to all eukaryotic proteins (36). This in silico analysis suggests that a comprehensive examination of Rab protein localization based on yeast Rab proteins has the potential to provide useful insights into the commonalities of eukaryotic cell biology.

Functionality of GFP-tagged constructs.

GFP tagging of small GTPases is a common method for creating a genetically encoded localization reporter. The GFP tag, however, is approximately the same size as the average Ras-related GTPase, and in most cases, possible interference with function has not been established. The functionality of our GFP-Rab constructs was first studied with the tagged construct under the control of the endogenous gene regulatory elements to ensure wild-type levels of the tagged proteins. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that the GFP-Rab proteins were expressed at levels comparable to those of the endogenous untagged proteins (data not shown). To determine whether GFP-tagged Rab proteins were still functional, we created tester strains for the essential Rab genes in S. cerevisiae, SEC4 and YPT1 (3, 27, 32, 44). These strains are deleted for the essential gene at the genomic locus and survive with a copy of the gene on a URA3-containing plasmid. Maintenance of the URA3 plasmid is impossible when cells are plated on the drug 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA), so cells can grow only if transformed with another plasmid containing an appropriate source of the essential gene, either SEC4 or YPT1. When these tester strains were transformed with GFP-tagged versions of SEC4 and YPT1, cells were able to survive on medium containing 5-FOA, whereas control plasmid-transformed cells were not (Fig. 2). The fact that we were able to obtain strains containing GFP-tagged versions of Sec4p and Ypt1p as the only sources of SEC4 and YPT1, respectively, indicates that the GFP-tagged constructs can provide function. However, we did observe differences in fitness between GFP-SEC4 and GFP-YPT1 in this assay. The tester strains were uniformly able to survive with GFP-SEC4 as the sole source of SEC4 in a manner indistinguishable to that with wild-type SEC4. This was not the case with GFP-YPT1, as only a subset of cells was able to utilize the tagged version as the sole source of YPT1 (Fig. 2A). These data suggest that the cells are more sensitive to NH2-terminal tagging of Ypt1p than to that of Sec4p and that there is a selective pressure for adaptation to the tagged version of GFP-YPT1 as the sole copy of YPT1. Consistent with this notion, GFP-SEC4 but not GFP-YPT1 constructs were able to suppress a temperature-sensitive mutant in the corresponding genes (data not shown).

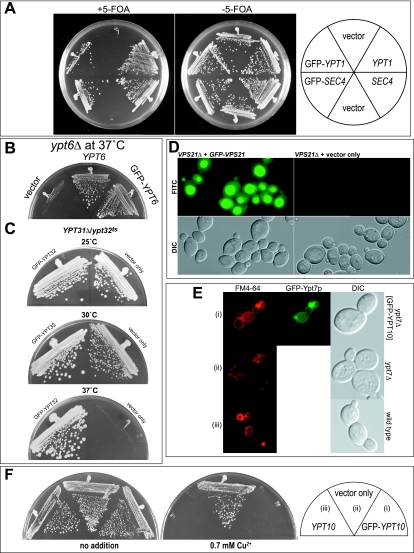

FIG. 2.

Functionality of GFP-tagged constructs. (A) GFP-tagged SEC4 and YPT1 constructs were transformed into SEC4Δ and YPT1Δ tester strains and streaked onto medium with (+) or without (−) 5-FOA at 25°C to assess functionality. This assay was performed in comparison to yeast transformed with empty vector as a negative control and wild-type SEC4 and YPT1 as positive controls. (B) ypt6Δ cells were assayed for survival at 37°C when transformed with empty vector-, YPT6-, or GFP-YPT6-containing plasmids. (C) ypt31Δ ypt31ts cells were assayed for the ability of GFP-tagged YPT31 to rescue growth at 37°C compared to that of vector alone. (D) vps21Δ cells were assayed for the uptake of lucifer yellow CH into the vacuole in the presence (+) or absence (−) of GFP-Vps21p. (E) ypt7Δ cells with GFP-YPT7 (i), vector only (ii), and wild-type YPT7 (iii) constructs were assayed for vacuolar morphologies with FM4-64. DIC, differential interference contrast. (F) ypt10Δ cells with GFP-YPT10 (i), vector only (ii), and wild-type YPT10 (iii) expressed behind the copper-inducible promoter PCUP1 were assayed for growth on media ± 0.7 mM CuSO4.

For the remaining, nonessential Rab genes, we tested the functionality of the GFP-tagged constructs according to published assays of their in vivo function. For GFP-Ypt6p functionality, we tested the ability of the plasmid to complement the ypt6Δ strain, which is temperature sensitive (39). GFP-YPT6 is functional and can complement ypt6Δ cells on YEPD at 37°C (Fig. 2B). To test the functionality of GFP-tagged YPT31 and YPT32, we made use of the strain carrying ypt31Δ ypt32ts, as these genes form a nonessential and redundant pair (4, 31), to demonstrate that GFP-YPT32 could provide function to rescue the thermosensitive phenotype (Fig. 2C). Similar results were also obtained for GFP-YPT31 (data not shown). Vps21p/Ypt51p is grouped together with Ypt52p and Ypt53p because of their high degree of sequence similarity, and among this group, vps21Δ cells show the most severe phenotype (53). We therefore selected Vps21p/Ypt51p as the representative of this group and determined the ability of GFP-VPS21 to complement the phenotype of vps21Δ cells. Ypt51p/Vps21p is required for endocytosis which can be measured by the uptake of the dye lucifer yellow CH into the yeast vacuole (15). GFP-Vps21p/Ypt51p was able to restore the inability of vps21Δ cells to accumulate lucifer yellow CH (Fig. 2D). We also determined the ability of GFP-tagged YPT7 to restore the fragmented vacuolar morphology phenotype associated with ypt7Δ cells. The results are shown in Fig. 2E, demonstrating that vacuolar morphology of ypt7Δ cells can be restored to a morphology indistinguishable from that of wild-type cells by the addition of GFP-YPT7. These data suggest that the tagged Ypt7p can function equivalently to the untagged protein. No functions have been described for the Rab protein Ypt10p or Ypt11p, and mutants with deletions of the genes encoding either protein have no apparent phenotype; however, Ypt10p is known to be deleterious to cell growth when overexpressed (38). We asked whether the overexpression of GFP-YPT10 would result in similar growth inhibition. YPT10 and GFP-YPT10, together with a vector-only control, were expressed from the copper-inducible promoter PCUP1. A copper-dependent growth inhibition was observed for both YPT10 and GFP-YPT10 (Fig. 2F), indicating that the GFP tag does not interfere with the ability of Ypt10p overexpression to generate a dominant-negative phenotype.

Rab protein localization.

Our data suggested that the NH2-terminal GFP tag is benign when appended to Rab proteins and can be used with confidence that the tag does not interfere with the functions of the wild-type protein. We took the entire complement of yeast Rab proteins tagged with GFP in both yeast and mammalian expression plasmids and examined their localizations in yeast and transfected tissue culture cells. In yeast, the GFP-tagged Rabs were expressed at endogenous levels as the sole copy of the Rab protein, i.e., in the absence of untagged wild-type Rab protein. In mammalian cells, the GFP-Rabs were expressed behind the viral cytomegalovirus promoter and transfections were typically allowed to proceed for 6 h.

The Rab6 family, Ypt6p.

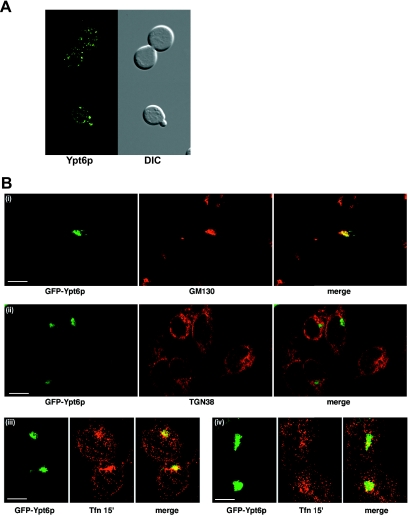

Ypt6p is a Golgi-localized yeast Rab and is thought to function in late Golgi transport, although the exact steps are not defined (60). When we expressed GFP-Ytp6p in yeast, we observed a distinct Golgi-like distribution, with little or no polarized distribution of the puncta (Fig. 3A). Likewise, when GFP-Ypt6p was expressed in mammalian cells, we found extensive colocalization with a Golgi marker, GM130 (Fig. 3B, panel i), but little or no colocalization with TGN38, a marker of the trans-Golgi network (TGN) (Fig. 3B, panel ii). Recently, Ypt6p has been identified as the homolog of Rab6a′, which is involved in the transport of early/recycling endosome to the TGN (41). To investigate whether GFP-Ypt6p might function in a similar manner, we carried out colocalization studies with transferrin, a marker of early/recycling endosomes. Transferrin was internalized for 15 min and, in a subpopulation of cells, appeared in a discrete perinuclear location reminiscent of those of recycling endosomes, which showed significant colocalization with GFP-Ypt6p (Fig. 3B, panel iii). In other cells, transferrin was more scattered in a distribution more reminiscent of early endosomes. In this case, there was only limited colocalization with GFP-Ypt6p (Fig. 3B, panel iv). Overall, our data suggest that Ypt6p is involved in Golgi communication with recycling endosomes as shown for Rab6a′.

FIG. 3.

Localization of GFP-Ypt6p in yeast and HeLa cells. (A) GFP-Ypt6p was expressed in yeast cells, and live cells were viewed by epifluorescence microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal is presented with differential interference contrast (DIC) images of the same cells. (B) GFP-Ypt6p was expressed in HeLa cells, and fixed cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal is compared to those of antibody markers for the following cellular compartments: (i) Golgi apparatus GM130, (ii) trans-Golgi network TGN38, and (iii and iv) transferrin internalized for 15 min. In each case, a merge of the two fluorescence images is shown. Bars = 10 μm.

The Rab5 family, Vps21/Ypt51p, Ypt52p, and Ypt52p.

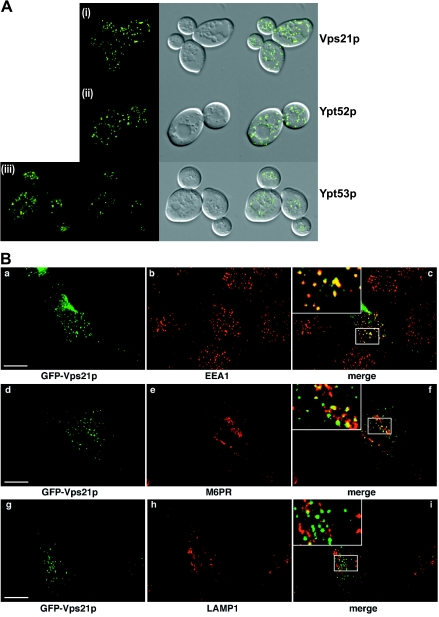

Ypt51p (Vps21p) is the yeast counterpart of mammalian Rab5 both in localization and in function (28, 53, 54). Ypt51p is grouped together with Ypt52p and Ypt53p because of a high degree of sequence similarity. All three of these Ypt proteins appear to function in endocytosis in yeast cells (53); however, the specific designation of each of the Ypts to a defined endocytic compartment has proven elusive. When we expressed GFP-Vps21p, it localized to numerous small puncta in yeast cells that were dispersed throughout the cell (Fig. 4A, panel i), the characteristic endosomal morphology. Although Ypt52p has been shown to function in endocytosis, a precise localization within the endocytic pathway has not been determined. We expressed GFP-Ypt52p in yeast cells and observed a characteristic pattern that consisted of puncta often larger than the GFP-Vps21p puncta that surrounded (but was excluded from) the vacuolar membrane as well as a few more scattered dots (Fig. 4A, panel ii). This distribution suggested an endosomal localization that was more advanced in the pathway (i.e., closer to the vacuole rather than the departure point of the plasma membrane) than that observed for Vps21p. The expression of GFP-Ypt53p in yeast cells showed a distinct (but relatively weak) localization to the vacuolar-limiting membrane, in addition to a small number of bright puncta (Fig. 4A, panel iii), many of which were clustered around the vacuole.

FIG.4.

Localization of GFP-Vps21p, GFP-Ypt52p, and GFP-Ypt53p in yeast and HeLa cells. (A) Localization of GFP-Vps21p, GFP-Ypt52p, and GFP-Ypt53p in yeast. (i) GFP-Vps21p was expressed in yeast cells, and live cells were viewed by epifluorescence microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal is presented with differential interference contrast images of the same cells. A merge of the two images is shown. (ii) GFP-Ypt52p-expressing yeast cells. Conditions were as described for panel i. (iii) GFP-Ypt53p-expressing yeast cells. Conditions were as described for panel i. (B) Localization of GFP-Ypt51p in HeLa cells. GFP-Vps21p was expressed in HeLa cells that were fixed and viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal was compared to those of antibody markers for the following cellular compartments: early endosomes (EEA1), late endosomes (M6PR), and late endosomes/lysosomes (LAMP1). In each case, a merge of the two fluorescence images is shown. Insets show selected areas enlarged approximately threefold, with color levels optimized to show colocalization. Bars = 10 μm. (C) Localization of GFP-Ypt52p in HeLa cells. GFP-Ypt52p was expressed in HeLa cells, and fixed cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal was compared to those of antibody markers for the following cellular compartments: early endosomes (EEA1), late endosomes (M6PR), and late endosomes/lysosomes (LAMP1). In each case, a merge of the two fluorescence images is shown. Insets show selected areas enlarged approximately threefold, with color levels optimized to show colocalization. Bars = 10 μm. (D) Localization of GFP-Ypt53p in HeLa cells. GFP-Ypt53p was expressed in HeLa cells, and fixed cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal was compared to those of antibody markers for the following cellular compartments: early endosomes (EEA1), late endosomes (M6PR), and late endosomes/lysosomes (LAMP1). In each case, a merge of the two fluorescence images is shown. Insets show selected areas enlarged approximately threefold, with color levels optimized to show colocalization. Bars = 10 μm.

In mammalian cells, GFP-Vps21p showed extensive colocalization with EEA1, a marker of early endosomes, as well as some colocalization with M6PR, a marker of endosomes that are in communication with the TGN (typically, but not exclusively, late endosomes) (20). GFP-Vps21p showed no significant colocalization with LAMP1, which is found in late endosomes and lysosomes (Fig. 4B). Based on these findings, we suggest that GFP-tagged Vps21p acts, like Rab5, in the formation of early endosomes. GFP-Ypt52p showed a pattern of localization similar to that of Vps21p in mammalian cells; however, it tended to colocalize more extensively with M6PR than with EEA1, again suggesting a post-Vps21p function (Fig. 4C). As with Vps21p, we saw no colocalization with LAMP1-positive vesicles. GFP-Ypt53p in animal cells showed a diffuse perinuclear distribution, which showed extensive colocalization with M6PR, combined with weaker and more-scattered dots that colocalized with EEA1 (Fig. 4D). GFP-Ypt53 also showed a distinct but limited degree of overlap with LAMP1. Overall, our results with Ypt53p suggest that it acts in the late endosome and is the third acting Rab in the functional Vps21p-Ypt52p-Ypt53p chain of endocytosis.

The Rab11 family, Ypt31p and Ypt32p.

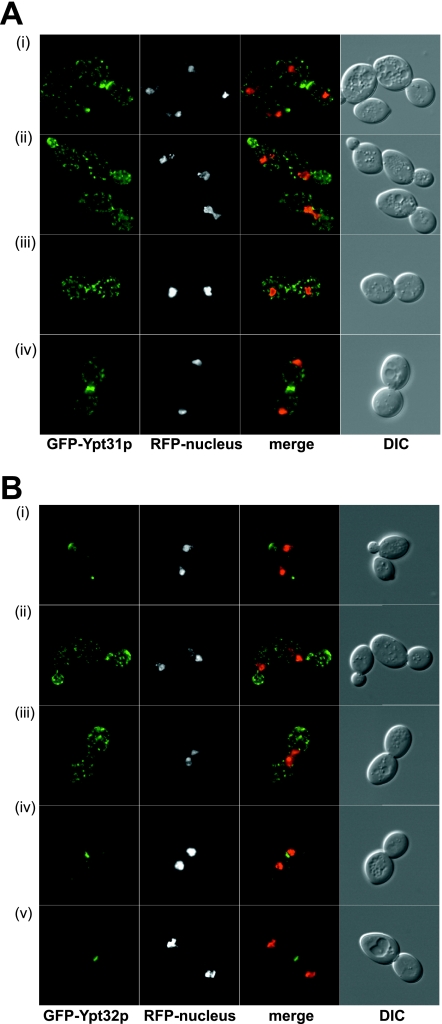

Ypt31p and Ypt32p are a functionally interchangeable and highly related pair of Rab proteins, homologous to mammalian Rab11 (22). Ypt31p and Ypt32p appear to function both within the Golgi (4, 31) and in post-Golgi trafficking events. Mutants in either protein show defects in Golgi function, and the immunofluorescence of Ypt31p is supportive of a Golgi apparatus-associated function. We independently expressed both GFP-Ypt31p and GFP-Ypt32p in yeast cells under conditions devoid of wild-type untagged protein (Fig. 5A and B). Because GFP-Ypt31/32p localization differs during the cell cycle, the inclusion of a RFP nuclear marker provided an independent assessment of the cell cycle status. In small budded cells, both proteins showed similar but not identical distributions. Ypt32p showed distinctive polarized bud tip staining (reminiscent of Sec4p) as well as some scattered Golgi-like dots (Fig. 5B). On the other hand, the polarized distribution of Ypt31p was less pronounced and was visible as a clustering of Golgi-like dots towards the bud tip (Fig. 5A). In dividing cells, we observed a quite different distribution of Ypt31p and Ypt32p. In this case, GFP-Ypt31p localized almost exclusively to the neck of the dividing cell, with fluorescence visible in a single discrete ring that probably represents the area of cytokinesis (compare Fig. 5A, panel iv, with B, panels iv and v). In this regard, Ypt31p shows localization very similar to those expected for Sec4p and Sec3p (18), proteins involved in polarized exocytosis. Ypt32p, on the other hand, showed scattered Golgi-like distribution, which was distributed approximately evenly between the two dividing cells but with some modest (compared to that for Ypt31p) enrichment in the vicinity of the neck during cytokinesis. To date, it has not been possible to functionally discriminate between Ypt31p and Ypt32p and these data suggest that Ypt31p and Ypt32 might have distinct roles in vivo.

FIG. 5.

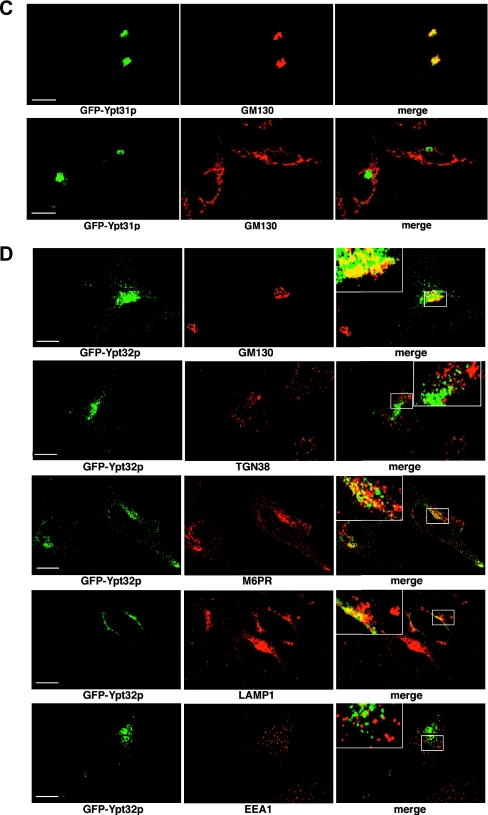

Localization of GFP-Ypt31p and GFP-Ypt32p in yeast and HeLa cells. (A) Localization of GFP-Ypt31p in yeast. GFP-Ypt31p-expressing live cells were viewed by fluorescence microscopy. GFP-Ypt31p localization was analyzed at various stages of the yeast cell cycle. A nuclear marker (Gal4BD-RFP) and the relative sizes of the mother and daughter cells were used to ascertain the cell cycle stage. The overlay of the GFP and RFP channels are of the maximum projection of each channel, and differential interference contrast (DIC) images were taken in one z plane. (B) Localization of GFP-Ypt32p in yeast. GFP-Ypt32p was expressed in yeast cells as the only copy, and live cells were viewed by fluorescence microscopy as described for panel A. (C) Localization of GFP-Ypt31p in HeLa cells. GFP-Ypt31p was expressed in HeLa cells, and fixed cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal was compared to those of antibody markers for the following cellular compartments: Golgi apparatus (GM130) and trans-Golgi network (TGN38). In each case, a merge of the two fluorescence images is shown. Bars = 10 μm. (D) Localization of GFP-Ypt32p in HeLa cells. GFP-Ypt32p was expressed in HeLa cells, and fixed cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal was compared to those of antibody markers for the following cellular compartments: Golgi apparatus (GM130) and trans-Golgi network (TGN38), late endosomes (M6PR), late endosomes/lysosomes (LAMP1), and early endosomes (EEA1). In each case, a merge of the two fluorescence images is shown. Insets show selected areas enlarged approximately threefold, with color levels optimized to show colocalization. Bars = 10 μm.

In order to address their possible different functions, we also localized both Ypt31p and Ypt32p in mammalian cells. Ypt31p showed almost exclusive colocalization with the Golgi marker GM130 and Rab11, with little or no TGN38 colocalization (Fig. 5C; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). GFP-Ypt32p also showed significant (but not exclusive) localization to the Golgi region based on GM130 colocalization, with little or no colocalization with TGN38 (Fig. 5D; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Because Ypt32p did not show exclusive Golgi localization, we further investigated its distribution alongside endosomal markers. We observed significant colocalization of Ypt32p with a marker of late endosomes (M6PR) as well as with LAMP1 (a marker of late endosomes/lysosomes) and Rab11 but only marginal colocalization with EEA1 (a marker of early endosomes). Overall, these data suggest that Ypt32p functions in a post-Golgi pathway that communicates with the late endosome, whereas Ypt31p acts in a more direct exocytic pathway, and this is, to our knowledge, the first functional distinction between these two isoforms.

Ypt10p and Ypt11p, the unknown yeast Rab proteins.

The yeast Rab proteins Ypt7p, Ypt1p, and Sec4p have been well characterized to localize to vacuolar, Golgi, and secretory vesicle membranes, respectively (23, 25, 47, 52, 64). We also examined the cross-species localization of these proteins with GFP and established that these proteins could be recruited to their cognate organelles in mammalian cells (see the supplemental material). Collectively, our results for previously studied yeast Rab proteins suggested the empirical rule that GFP-tagged Rabs display localizations equivalent to those of both the untagged protein in yeast and the orthologous compartments in animal cells. To further evaluate the hypothesis that the localization of Rab proteins in animal cells can be an independent line of evidence that supports presumed functions and localizations in S. cerevisiae, we next examined the uncharacterized Rab proteins Ypt10p and Ypt11p.

Ypt10p.

Ypt10p is a Rab protein whose overexpression is growth inhibitory with possible defects in vesicular traffic (38) but otherwise mysterious; its localization has not been determined. Our bioinformatics analysis did not reveal Ypt10p to be a member of a large subclass of Rab proteins. Ypt10p clusters adjacent to the endocytic Rab proteins and was most closely homologous to mammalian Rab20 proteins (Fig. 1). We expressed GFP-Ypt10p in yeast cells and observed a somewhat unusual distribution. In budding cells, the protein was localized to membranous structures, some of which were often in the shape of small puncta, often closely associated with the vacuolar membrane (Fig. 6A, panel i). In some cases, faint labeling of the plasma of the membrane was observed (Fig. 6A) and this was enhanced with the slight overexpression when the GFP-tagged YPT10 gene was driven from the PCUP1 promoter, which shows modest expression from cells grown in standard medium without the exogenous addition of Cu2+ (Fig. 6A, panel ii). To examine the association of Ypt10p with organelles of the endocytic pathway, we performed the colocalization of GFP-Ypt10p with vacuolar FM4-64 (61). Double-labeled cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy, with an optical slice taken from the cellular midsection to examine the coincidence of labels. FM4-64-stained vacuoles show good overlap with the GFP-Ypt10p-labeled puncta (Fig. 6A, panel iii), although the more peripheral, juxta-plasma membrane GFP-Ypt10p-labeled structures are not coincident with the vacuolar FM4-64. Overall, the localization of Ypt10p can be classified as peripheral endosomal/vacuolar. In HeLa cells, Ypt10p showed mostly a broad cytoplasmic distribution. The most obvious membranous localization was in ruffles at the cell surface, where GFP-Ypt10p showed significant colocalization with the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 6B). There was only limited colocalization with actin cables, as shown by TRITC-phalloidin labeling. In a subset of cells, we observed that GFP-Ypt10p localized to the membrane of large vesicles near the cell surface, which may be macropinosomes. The association with membrane ruffles was markedly increased when cells were stimulated with the phorbol ester PMA. Under these conditions, we observed that Rab11-positive recycling endosomes were also associated with Ypt10p and actin-rich areas of the cell periphery, although we saw no association of GFP-Ypt10p to Golgi structures labeled with GM130 or EEA1-labeled endosomes (Fig. 6B). Overall, our data suggest that YPT10 has functions in a regulated endosomal pathway.

FIG. 6.

Localization of GFP-Ypt10p in yeast and HeLa cells. (A) GFP-Ypt10p was expressed in yeast cells, live cells were viewed by epifluorescence microscopy, and fluorescence images were subjected to double-blind deconvolution. The GFP fluorescence signal is presented with a differential interference contrast (DIC) image of the same cells. A merge of the two images is shown. (i) GFP-Ypt10p expressed from endogenous promoter in ypt10Δ cells; (ii) GFP-Ypt10p expressed with PCUP1 (image shows basal expression of gene in absence of Cu3+ addition to media); (iii) live-cell imaging of GFP-Ypt10p in cells labeled with FM4-64 for 15 min followed by a 45-min washout to identify vacuolar membranes. (B) GFP-Ypt10p was expressed in HeLa cells, fixed and permeabilized, and labeled with TRITC-phalloidin to visualize the actin cytoskeleton. Cells were viewed by epifluorescence microscopy, and images were subjected to double-blind deconvolution. A single transverse slice though the cell is shown. GFP and TRITC-phalloidin are shown both individually and as a merged image. The panels below show GFP-Ypt10p in the periphery of the cell (i) and in conjunction with markers of the Golgi apparatus: GM130 (ii), GFP early endosome EEA1 (iii), and the recycling endosome for Rab11 (iv).For panels ii, iii, and iv, GFP and antibody markers are shown in separate images.

Ypt11p.

The function and localization of Ypt11p are enigmatic. It is known to interact with the class V myosin Myo2p and is required for the retention of newly inherited mitochondria (13, 30). The organelle on which Ypt11p resides, however, has not been identified. Ypt11p is unusual among Rab proteins; with 417 residues, it is significantly larger than the average Ypt/Rab protein (for comparison, Ypt1p is 207 residues). The majority of this extra length is derived from three additions/inserts: an NH2-terminal extension of 82 residues, an approximately 59-residue large insert between L1 and α1, and a 35-amino-acid insert between β3 and L4. Our bioinformatic analysis (Fig. 1B) places Ypt11p in a group with Rab proteins of biosynthetic/exocytic function situated within the general “Rab8” group, with Sec4p being its closest yeast paralog. We expressed GFP-Ypt11p in yeast cells and observed a somewhat polarized distribution, along with a distinct reticular pattern that surrounded the nucleus (Fig. 7A) and underlying the cell cortex, strongly indicative of localization to the yeast ER. To confirm the ER localization, the cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy in conjunction with monoclonal antibodies against a known ER marker, Pdi1p. The results (Fig. 7B) show extensive colocalization of the GFP-Ypt11p with Pdi1p, with an especially prominent ring surrounding the nucleus (stained with Hoechst). In general, Pdi1p is evenly distributed throughout the ER, whereas GFP-Ypt11p is preferentially enriched in the peripheral ERs of daughter cells and small buds.

FIG. 7.

Localization of GFP-Ypt11p in yeast and HeLa cells. (A) GFP-Ypt11p was expressed in yeast cells, and live cells were stained with Hoechst 33258. Cells were viewed by epifluorescence microscopy, and fluorescence images were subjected to double-blind deconvolution. The GFP fluorescence signal is presented with a differential interference contrast (DIC) image of the same cells, and a merge of the three images is shown. (B) GFP-Ypt11p was expressed in yeast cells, fixed, and stained with Hoechst 33258. Cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using anti-Pdi1p antibodies. The GFP and immunofluorescence signal is presented with a differential interference contrast (DIC) image of the same cells. (C) GFP-Ypt11p was expressed in BHK cells and viewed by epifluorescence microscopy, and fluorescence images were subjected to double-blind deconvolution. Both a maximum projection and a single slice through the cell are shown. (D) GFP-Ypt11p was expressed in BHK cells and live cells incubated with ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX. Cells were fixed and viewed by epifluorescence microscopy. The GFP and ER-Tracker DPX signals are shown individually, and in a merged image with ER-Tracker DPX false-colored red to show colocalization with GFP. (E) GFP-Ypt11p was expressed in HeLa cells, and fixed cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal was compared to that of an antibody marker for the endoplasmic reticulum, PDI. Images show the periphery of the cell both individually and as a merge of the two fluorescence images. (F) GFP-Ypt11p was expressed in BHK cells, and fixed cells were viewed by confocal microscopy. The GFP fluorescence signal was compared to that of an antibody marker for the ERGIC, KDEL receptor (KDEL-R). GFP and the KDEL-R are shown both individually and as a merged image. In the lower panels, the cells were incubated for 3 h at 15°C before fixation.

To more clearly elucidate Ypt11p function, we expressed GFP-Ypt11p in mammalian cells. BHK cells expressing Ypt11p showed a predominant localization to the nuclear envelope as well as a discrete reticular pattern extending to the periphery of the cell, combined with a more polarized perinuclear distribution suggestive of the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 7C). As with Ypt7p, there was also occasional nonspecific localization of Ypt11p to the nucleus in more highly expressing cells. The reticular pattern was coincident with ER tracker DPX (Fig. 7D) and showed distinct colocalization with the ER marker PDI, especially at the periphery of the cell (Fig. 7E). To investigate the perinuclear association of GFP-Ypt11p, we performed colocalization studies with the KDEL receptor, a marker of the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) (59). We observed extensive colocalization of GFP-Ypt11p with the KDEL receptor, especially in the perinuclear region of the cell (Fig. 7F, upper panel). Proteins of the ERGIC can be relocalized to punctate structures distributed throughout the cytoplasm by incubating the cells at 15°C (58). We therefore carried out confocal microscopy of GFP-Ypt11p-transfected BHK cells and shifted the temperature to 15°C for 3 h prior to fixation. The KDEL receptor and GFP-Ypt11p both showed a redistribution under these conditions (Fig. 7F, lower panel), confirming their association with the ERGIC. Overall, GFP-Ypt11p localized to the ER and ERGIC in mammalian cells. We found no significant colocalization with markers of recycling endosomes, a localization that has recently been proposed for Ypt11p in mammalian cells (33), or with mitochondria, which have been functionally correlated with Ypt11p expression (6, 30) (data not shown). Overall, our data demonstrate that Ypt11p is located on the ER and enriched in the peripheral ER of the daughter cell, suggestive of the functions in this organelle.

The distinctive localization of Ypt11p, with its partial polarization in the peripheral ER of the daughter cell, suggested a possible role in ER inheritance. In order to determine whether Ypt11 plays any role in ER inheritance, we made use of two parallel markers to assay ER distribution. The markers examined were the polytopic membrane proteins Hmg1p and Sec61p. Hmg1p is involved in the sterol biosynthesis pathway, is not thought to physically associate with other proteins, and has been extensively used as a marker to examine ER inheritance (12, 14, 26). Sec61p heteromultimerizes to form the protein translocon channel in the rough ER. We used these two proteins to ensure that our observations would follow the fate of the ER membrane and be marker independent. Experiments were carried out using wild-type, ypt11Δ, and as a positive control, myo4Δ cells, which have previously been reported to be deficient in daughter cell ER inheritance (16). Cells were grown on rich medium at 30°C, resuspended in nonfluorescent medium and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. A z series of images was collected throughout the thickness of the cell, and images containing the plane going through the bud neck were kept for further analysis. Representative images are shown in Fig. 8A and B. The intensity of the cortical ER in the mother and the bud was quantified, as well as the area of the bud and the mother cell, using Image J (Fig. 8C and D). As shown in Fig. 8A and B, in wild-type cells, the ER reticulum localizes around the nucleus as well as at the mother and the bud cortex. In the myo4Δ cell strain, our positive control, the Hmg1p-GFP signal was significantly diminished in the daughter cells (Fig. 8A and C). The effect seen with Sec61p-GFP (Fig. 8B and D) showed a similar trend, although it was much weaker overall, suggesting that the effect is at least partially marker specific. Strikingly, ypt11Δ mutant cells showed an effect similar to that of myo4Δ cells (Table 1). The effect observed in the double mutant myo4Δ ypt11Δ was severely pronounced: with the Hmg1p-GFP assay, we found that only 50% of the signal, with an average fluorescence intensity ratio of 0.51 ± 0.023, was present in the bud of the double mutant compared to that for wild-type cells, with an average fluorescence intensity ratio of 1.1 ± 0.06. The tendency was the same with Sec61p-GFP, even though the degree to which it was affected differed. These data are summarized in Table 1. In all cases, the mean fluorescence intensity of mother cell/bud was independent of the size of the bud and the surface area (volume) of mother to the surface area of the bud. As a control, we calculated the ratio of the intensity of the nucleus over the intensity of the mother cortex, with no significant difference being observed between the different mutants, indicating that the defect is in inheritance of peripheral, cortical ER and not a result of general cortical organization defects (data not shown). We also examined ER morphology since it has been previously established that some mutations that affect ER morphology at the cortex can give rise to an ER inheritance phenotype (17). ER morphology was checked with a close examination of the network morphology at the cell cortex. Neither mutant nor double-mutant cells showed any impairment of the morphological structure of the ER network at the surface (data not shown). Thus, ypt11Δ affect ER inheritance in a manner similar to that of myo4Δ, which is independent of ER morphology.

FIG. 8.

ypt11Δ cells influence the inheritance of ER membrane markers to a similar extent as observed for myo4Δ cells. (A) Wild-type, myo4Δ, ypt11Δ, and myo4Δ ypt11Δ cells expressing Hmg1p-GFP at the endogenous locus were grown to mid-log phase at 30°C in rich medium and then resuspended in nonfluorescent medium. A z stack image was taken, with the plane going through the bud neck being kept for further investigation. Representative pictures are shown for each genotype. (B) Wild-type, myo4Δ, ypt11Δ, and myo4Δ ypt11Δ cells expressing Sec61p-GFP were photographed as described for panel A. Images were processed as for panel A, with a representative picture shown for each genotype. (C and D) Pictures shown in panel A (C) or B (D) were analyzed using Image J 1.29 software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Four sets of data were extracted from the photographs: the intensity signal of the bud cortex, the intensity signal of the mother cortex, the area of the bud, and the area of the mother. Each dot represents one cell and is the ratio of the intensity of the bud cortex/intensity of the mother cortex over the area of the bud/the area of the mother. The experiment was repeated three times, and only one of the experiments is represented in the graph; the tendencies were similar in all three experiments. Table 1 shows a summary quantification of the data set.

TABLE 1.

Average fluorescence intensity ratio of Sec61p-GFP and Hmg1p-GFP markers

| Marker | Bud/mother ratio (mean ± SE) |

|---|---|

| Sec61p-GFP | |

| Wild type | 1.11 ± 0.035 |

| ypt11Δ | 0.90 ± 0.038 |

| myo4Δ | 0.99 ± 0.038 |

| ypt11Δ myo4Δ | 0.88 ± 0.023 |

| Hmg1p-GFP | |

| Wild type | 1.17 ± 0.06 |

| ypt11Δ | 0.96 ± 0.055 |

| myo4Δ | 0.81 ± 0.03 |

| ypt11Δ myo4Δ | 0.51 ± 0.023 |

Functional conservation of Rab-GDI.

Our experiments demonstrate a striking cross-species conservation of Rab protein localization, showing that Rab proteins can be recruited to cognate organelles over large evolutionary distances. In turn, this implies that the machinery responsible for recruiting Rab proteins onto membranes is probably functionally conserved. Very little is known about the molecular nature of the machinery that is responsible for the specific subcellular localization of Rab proteins. Rab protein prenyl moiety is required but not sufficient (7, 21). Rab proteins exist in two pools, a cytoplasmic pool and a membrane-associated pool, with the cytoplasmic pool serving as the reservoir from which organelles recruit their specific Rabs. The cytoplasmic pool of Rab proteins exists in a complex with Rab-GDI; there is currently no other protein known to associate with Rab proteins in the cytoplasm. Rab-GDI therefore plays a critical role in Rab protein localization because the exclusive substrate for membrane recruitment of Rab proteins is a cytosolic heterodimer of a Rab protein with Rab-GDI. Moreover, Rab-GDI is a global regulator for Rab proteins, as yeasts contain a single Rab-GDI gene, SEC19, which acts on all Rab proteins. This appears to be a general rule with between one and three Rab-GDI-encoding genes that act on multiple Rab proteins found in the genomes of several eukaryotes. To test the functional conservation of Rab-GDI, we expressed the mammalian version of Rab-GDI in yeast behind a regulatable promoter, the galactose promoter which expresses at high levels in cells grown in medium with galactose as a carbon source and is highly repressed in the presence of glucose. We tested the ability of this construct to suppress a conditional lethal allele of Rab-GDI, sec19-1, and also determined whether cells could survive on galactose with mammalian Rab-GDI in place of the SEC19 gene. The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 9; the mammalian Rab-GDI construct can suppress the temperature sensitivity of sec19-1 (Fig. 9A) and also serve as the sole source of Rab-GDI, an essential gene function in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 9B). This effect was apparent only upon the overexpression of the mammalian Rab-GDI construct; the expression level when the mammalian Rab-GDI ORF was placed under the control of the endogenous SEC19 5′ and 3′ regions was not sufficient to provide Rab-GDI function (data not shown). These data demonstrate that the essential function of Rab-GDI is conserved from yeast to humans; underlying the functional conservation of Rab protein localization is a conservation of Rab-GDI function.

FIG. 9.

Functional replacement of SEC19/GDI1 with mammalian Rab-GDI. (A) sec19-1 suppression. sec19-1 cells were transformed with the following plasmids: (1) empty vector, (2) mammalian Rab-GDI, (3) SEC19/GDI1-positive control, as indicated before testing for growth on the permissive and restrictive temperature on yeast-peptone medium containing 1.5% raffinose with 0.5% galactose. (B) Ability of mammalian Rab-GDI constructs to serve as the sole source of yeast SEC19/GDI1. GDI1Δ cells were transformed with constructs as indicated before testing for growth on 5-FOA-containing plates with either glucose or galactose as a carbon source. These constructs are indicated in the plate schematic.

DISCUSSION

Comparative genomic studies in cell biology.

In this study, we have identified 10 major clusters or groups of Rab sequences that we have termed the Rab5, Rab7, Rab6, Rab4, Rab28, Rab38, Rab11, Rab1, Rab8, and Rab3 groups. This bioinformatic analysis reveals that yeast Rab proteins, with one exception, can be located in global Rab sequence space together with a cluster of homologs from other diverse eukaryotes. The 11 yeast Rab sequences are not distributed among major Rab sequence clusters or subclasses; rather, these sequences are derived from six of the major Rab subclasses identified by our bioinformatic analysis. This may not be surprising as S. cerevisiae seems to lack many of the organelles possessed by other single-celled eukaryotes (e.g., the rhoptries of Toxoplasma) and the specialized organelles located in the differentiated cells of metazoa. Although it is too simplistic to assume that the number of Rab proteins correlates with the number and complexity of organelles, it is clear that Rab proteins can be multifunctional so it is possible that the Rab proteins of S. cerevisiae cover necessary functions that are provided by different Rab subclasses in other species. Certainly our localization data support the notion that Rab proteins of the same subclass may have both overlapping and distinct functions.

Our results show that the GFP-tagged Rab proteins maintain localization between single-celled eukaryotes and mammalian tissue culture cells. This in turn implies that the localization of a protein in animal cells can both confirm organelle residency and give us more information about the identity of the organelle and the other organelles it directly communicates with via membrane traffic. For Rab proteins of known functions, we were able to demonstrate that the yeast Rab protein localizes to an organelle in higher eukaryotes that is the cognate of the organelle on which the Rab protein resides in yeast. The advantages of this approach are severalfold. First, it provides an independent cross-check of localization assignment, which is often a technical issue in yeast with its small size and limited spatial resolution. Second, this analysis demonstrates that cross-species experiments can be very valuable in ascertaining the correct locations of novel proteins and it will be valuable to extend these studies to multicellular model organisms. In addition, these studies have practical implications of increasing the availability of well-characterized markers in the membrane-trafficking pathway.

Role of Ypt10p and Ypt11p.

The existence of the two yeast Rabs Ypt10p and Ypt11p was revealed only upon the sequencing of the yeast genome, and these ORFs remain functionally uncharacterized. Little is known about Ypt10p other than the observation of possible defects in vesicular traffic upon the overexpression of Ypt10p (38). To date, no function or localization has been assigned to Ypt11p. The results of an analysis of the relative localization patterns in yeast and mammalian cells with Rab proteins of known functions suggested that we could extrapolate from these experiments to help understand the roles of Ypt10p and Ypt11p.

A sequence analysis of Ypt10p suggested an endocytic function for Ypt10p since it clusters with Rab protein sequences of known endocytic function in global Rab sequence space. The pattern of Ypt10p localization in HeLa cells was very similar to that reported for Rab34 in mouse 10T1/2 fibroblasts (56); however, we saw no significant localization to the Golgi apparatus, another reported localization of Rab34 (62), or with EEA1. As with Rab34 (56), the association with membrane ruffles was markedly increased when cells were stimulated with the phorbol ester PMA. Our phylogenetic analysis shows that Ypt10p is closest to the Rab20 sequences from vertebrates. Rab20 has been reported to be localized to apical-dense tubules, endocytic structures underlying the apical surfaces of polarized epithelial cells (40). We propose that the major localization of Ypt10p and its orthologs, such as Rab20, is in endocytic structures, where it functions in plasma membrane remodeling.

Together, the bioinformatics and localization of, and functional observations of the effect of, ypt11Δ suggest a role for Ypt11p in the biosynthetic secretory pathway in the control of ER inheritance. Myo4p and Ypt11p are likely to work in parallel pathways to act synergistically in the transport of the ER membrane to the bud cortex, although other explanations are possible. Interestingly, even in cells with the most-severe defects, some ER membrane was always seen at the bud cortex, suggesting that ypt11Δ and myo4Δ cells are not totally deficient in ER inheritance and that a third pathway exists, perhaps under the control of Sec8p (48). Ypt11p has been reported to cause defects in mitochondrial inheritance (6, 30); our work demonstrates a localization of Ypt11p on the ER and a role for Ypt11p in ER inheritance. Many cell types show a close apposition of the ER with mitochondria (5, 19, 42, 43); one explanation to reconcile these two observations would be that the mitochondrial inheritance defect of ypt11Δ cells is a consequence of their failure to inherit ER.

Mechanism of Rab protein localization.

A characteristic feature of a Rab protein is its steady-state localization to the cytosolic surface of a particular subcellular membrane. Our results reveal fundamental similarities between divergent species, underlying conservation of the basic mechanism of Rab membrane localization. Each Rab protein has a unique localization mediated in part by COOH-terminal hypervariable sequences that lie just prior to the site of double geranylgeranylation (2, 9). The machinery that decodes these signals is not well understood, with one exception, which is the participation of Rab-GDI. Rab-GDI forms a cytosolic heterodimer with Rab proteins, and it is this complex that is the substrate for membrane recruitment of Rab proteins, although it is not known whether Rab-GDI is an active or a passive player in this process. We show here that mammalian Rab-GDI can functionally substitute for its S. cerevisiae counterpart, demonstrating that the essential function of Rab-GDI, a known component of the Rab membrane recruitment mechanism, is conserved from yeast to humans. The functional compensation could be seen only when the mammalian protein was expressed at high levels. Higher-level expression may be needed to engage in critical protein-protein interactions, which have coevolved with the yeast Rab-GDI. These protein interactions may relate to how mammalian Rab-GDI associates with Rab proteins or other proteins that regulate GDI activity, such as GDI displacement factors or Rab recycling factors (45, 50), whose molecular identity in S. cerevisiae remain undefined. Mammalian Rab-GDI, like yeast Rab-GDI, has the capability of interacting with a wide range of Rab proteins; therefore, the first possibility (that the reduced performance of mammalian Rab-GDI in yeast cells is due to compromises in Rab protein interaction) may be less likely. If this is the case, a screen to uncover alleles that allow mammalian Rab-GDI to functionally substitute for yeast Rab-GDI at regular expression levels may identify regulators of Rab-GDI function.

Methodology and implications for large-scale applications.

Global localization analyses of the proteome have relied on COOH-terminal tagging (29, 34). In the case of Rab proteins, COOH-terminal tagging destroys protein localization due to the destruction of the prenylation motif at the COOH terminus of the protein that is a prerequisite for membrane association. In this study, we investigated the function and localization of the yeast genomic complement of Rab proteins tagged at the NH2 terminus. While GFP-tagged Rabs have been widely used as organelle markers, it is not clear whether Rab proteins retain functionality when tagged with this marker. In general, the localization patterns of genome-integrated, single-copy constructs and centromeric plasmid-borne constructs were identical and also in good agreement, where known, with published data derived from immunofluorescence-labeling protocols. Our results demonstrate that the GFP tag can be used to provide insights into the localization of Rab proteins and can also be used with a high degree of confidence that the resulting constructs possessauthentic and nearly authentic wild-type function. For instance, GFP-tagged Sec4p and GFP-tagged Ypt1p were able to function as the sole cellular sources of these essential genes in the presence of a deleted wild-type gene (Fig. 2). However, these results also suggest that some Rab proteins (e.g., Ypt1p, out of the seven tested here) are more sensitive to the GFP tag than others and that, even when replacing an essential gene with the GFP-tagged version, we cannot discount the possibility that there is some compromise in fitness that is not apparent in an otherwise wild-type cell.

In summary, our systematic genome-wide investigation demonstrates the conservation of Rab localization between yeast and mammalian cells. These data underscore the importance of correct Rab protein localization for the regulation and organization of membrane traffic and demonstrate the utility of S. cerevisiae for the elucidation of pathways and mechanisms for Rab protein localization by revealing a novel function for Ypt11p in ER inheritance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health in the United States.

The Hmg1p-GFP construct was a kind gift of Susan Ferro-Novick. Many thanks go to Ian Berke and Holger Sondermann for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, B. R., and M. C. Seabra. 2005. Targeting of Rab GTPases to cellular membranes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33:652-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali, B. R., C. Wasmeier, L. Lamoreux, M. Strom, and M. C. Seabra. 2004. Multiple regions contribute to membrane targeting of Rab GTPases. J. Cell Sci. 117:6401-6412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacon, R. A., A. Salminen, H. Ruohola, P. Novick, and S. Ferro-Novick. 1989. The GTP-binding protein Ypt1 is required for transport in vitro: the Golgi apparatus is defective in ypt1 mutants. J. Cell Biol. 109:1015-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benli, M., F. Doring, D. G. Robinson, X. Yang, and D. Gallwitz. 1996. Two GTPase isoforms, Ypt31p and Ypt32p, are essential for Golgi function in yeast. EMBO J. 15:6460-6475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bereiter-Hahn, J. 1990. Behavior of mitochondria in the living cell. Int. Rev. Cytol. 122:1-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boldogh, I. R., S. L. Ramcharan, H. C. Yang, and L. A. Pon. 2004. A type V myosin (Myo2p) and a Rab-like G-protein (Ypt11p) are required for retention of newly inherited mitochondria in yeast cells during cell division. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:3994-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calero, M., C. Z. Chen, W. Zhu, N. Winand, K. A. Havas, P. M. Gilbert, C. G. Burd, and R. N. Collins. 2003. Dual prenylation is required for Rab protein localization and function. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:1852-1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calero, M., G. R. Whittaker, and R. N. Collins. 2001. Yop1p, the yeast homolog of the polyposis locus protein 1, interacts with Yip1p and negatively regulates cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 276:12100-12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavrier, P., J. P. Gorvel, E. Stelzer, K. Simons, J. Gruenberg, and M. Zerial. 1991. Hypervariable C-terminal domain of Rab proteins acts as a targeting signal. Nature 353:769-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavrier, P., M. Vingron, C. Sander, K. Simons, and M. Zerial. 1990. Molecular cloning of YPT1/SEC4-related cDNAs from an epithelial cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10:6578-6585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins, R. N. 2005. Application of phylogenetic algorithms to assess Rab functional relationships. Methods Enzymol. 403:19-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cronin, S. R., A. Khoury, D. K. Ferry, and R. Y. Hampton. 2000. Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase degradation requires the P-type ATPase Cod1p/Spf1p. J. Cell Biol. 148:915-924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du, Y., S. Ferro-Novick, and P. Novick. 2004. Dynamics and inheritance of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci. 117:2871-2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du, Y., M. Pypaert, P. Novick, and S. Ferro-Novick. 2001. Aux1p/Swa2p is required for cortical endoplasmic reticulum inheritance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2614-2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dulic, V., M. Egerton, I. Elguindi, S. Raths, B. Singer, and H. Riezman. 1991. Yeast endocytosis assays. Methods Enzymol. 194:697-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estrada, P., J. Kim, J. Coleman, L. Walker, B. Dunn, P. Takizawa, P. Novick, and S. Ferro-Novick. 2003. Myo4p and She3p are required for cortical ER inheritance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 163:1255-1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estrada de Martin, P., Y. Du, P. Novick, and S. Ferro-Novick. 2005. Ice2p is important for the distribution and structure of the cortical ER network in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 118:65-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finger, F. P., T. E. Hughes, and P. Novick. 1998. Sec3p is a spatial landmark for polarized secretion in budding yeast. Cell 92:559-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franke, W. W., and J. Kartenbeck. 1971. Outer mitochondrial membrane continuous with endoplasmic reticulum. Protoplasma 73:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh, P., N. M. Dahms, and S. Kornfeld. 2003. Mannose 6-phosphate receptors: new twists in the tale. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4:202-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomes, A. Q., B. R. Ali, J. S. Ramalho, R. F. Godfrey, D. C. Barral, A. N. Hume, and M. C. Seabra. 2003. Membrane targeting of Rab GTPases is influenced by the prenylation motif. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:1882-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotte, M., T. Lazar, J. S. Yoo, D. Scheglmann, and D. Gallwitz. 2000. The full complement of yeast Ypt/Rab-GTPases and their involvement in exo- and endocytic trafficking. Subcell. Biochem. 34:133-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goud, B., A. Salminen, N. C. Walworth, and P. J. Novick. 1988. A GTP-binding protein required for secretion rapidly associates with secretory vesicles and the plasma membrane in yeast. Cell 53:753-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurkan, C., H. Lapp, C. Alory, A. I. Su, J. B. Hogenesch, and W. E. Balch. 2005. Large-scale profiling of Rab GTPase trafficking networks: the membrome. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:3847-3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haas, A., D. Scheglmann, T. Lazar, D. Gallwitz, and W. Wickner. 1995. The GTPase Ypt7p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required on both partner vacuoles for the homotypic fusion step of vacuole inheritance. EMBO J. 14:5258-5270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hampton, R. Y., A. Koning, R. Wright, and J. Rine. 1996. In vivo examination of membrane protein localization and degradation with green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:828-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haubruck, H., C. Disela, P. Wagner, and D. Gallwitz. 1987. The Ras-related ypt protein is an ubiquitous eukaryotic protein: isolation and sequence analysis of mouse cDNA clones highly homologous to the yeast YPT1 gene. EMBO J. 6:4049-4053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horazdovsky, B. F., G. R. Busch, and S. D. Emr. 1994. VPS21 encodes a rab5-like GTP binding protein that is required for the sorting of yeast vacuolar proteins. EMBO J. 13:1297-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huh, W. K., J. V. Falvo, L. C. Gerke, A. S. Carroll, R. W. Howson, J. S. Weissman, and E. K. O'Shea. 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425:686-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Itoh, T., A. Watabe, E. A. Toh, and Y. Matsui. 2002. Complex formation with Ypt11p, a Rab-type small GTPase, is essential to facilitate the function of Myo2p, a class V myosin, in mitochondrial distribution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7744-7757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jedd, G., J. Mulholland, and N. Segev. 1997. Two new Ypt GTPases are required for exit from the yeast trans-Golgi compartment. J. Cell Biol. 137:563-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jedd, G., C. Richardson, R. Litt, and N. Segev. 1995. The Ypt1 GTPase is essential for the first two steps of the yeast secretory pathway. J. Cell Biol. 131:583-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kail, M., M. Hollinshead, M. Kaufmann, J. Boettcher, D. Vaux, and A. Barnekow. 2005. Yeast Ypt11 is targeted to recycling endosomes in mammalian cells. Biol. Cell 97:651-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar, A., S. Agarwal, J. A. Heyman, S. Matson, M. Heidtman, S. Piccirillo, L. Umansky, A. Drawid, R. Jansen, Y. Liu, K. H. Cheung, P. Miller, M. Gerstein, G. S. Roeder, and M. Snyder. 2002. Subcellular localization of the yeast proteome. Genes Dev. 16:707-719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lal, K., M. C. Field, J. M. Carlton, J. Warwicker, and R. P. Hirt. 2005. Identification of a very large Rab GTPase family in the parasitic protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 143:226-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lazar, T., M. Gotte, and D. Gallwitz. 1997. Vesicular transport: how many Ypt/Rab-GTPases make a eukaryotic cell? Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:468-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Louvet, O., O. Roumanie, C. Barthe, M. F. Peypouquet, J. Schaeffer, F. Doignon, and M. Crouzet. 1999. Characterization of the ORF YBR264c in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which encodes a new yeast Ypt that is degraded by a proteasome-dependent mechanism. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:589-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo, Z., and D. Gallwitz. 2003. Biochemical and genetic evidence for the involvement of yeast Ypt6-GTPase in protein retrieval to different Golgi compartments. J. Biol. Chem. 278:791-799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lutcke, A., R. G. Parton, C. Murphy, V. M. Olkkonen, P. Dupree, A. Valencia, K. Simons, and M. Zerial. 1994. Cloning and subcellular localization of novel Rab proteins reveals polarized and cell type-specific expression. J. Cell Sci. 107:3437-3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mallard, F., B. L. Tang, T. Galli, D. Tenza, A. Saint-Pol, X. Yue, C. Antony, W. Hong, B. Goud, and L. Johannes. 2002. Early/recycling endosomes-to-TGN transport involves two SNARE complexes and a Rab6 isoform. J. Cell Biol. 156:653-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montisano, D. F., J. Cascarano, C. B. Pickett, and T. W. James. 1982. Association between mitochondria and rough endoplasmic reticulum in rat liver. Anat. Rec. 203:441-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore, D. J., W. D. Merritt, and C. A. Lembi. 1971. Connections between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in rat liver and onion stem. Protoplasma 73:43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novick, P., and P. Brennwald. 1993. Friends and family: the role of the Rab GTPases in vesicular traffic. Cell 75:597-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pfeffer, S., and D. Aivazian. 2004. Targeting Rab GTPases to distinct membrane compartments. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:886-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pfeffer, S. R. 2001. Rab GTPases: specifying and deciphering organelle identity and function. Trends Cell Biol. 11:487-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plutner, H., A. D. Cox, S. Pind, R. Khosravi-Far, J. R. Bourne, R. Schwaninger, C. J. Der, and W. E. Balch. 1991. Rab1b regulates vesicular transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and successive Golgi compartments. J. Cell Biol. 115:31-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reinke, C. A., P. Kozik, and B. S. Glick. 2004. Golgi inheritance in small buds of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is linked to endoplasmic reticulum inheritance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:18018-18023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saito-Nakano, Y., B. J. Loftus, N. Hall, and T. Nozaki. 2005. The diversity of Rab GTPases in Entamoeba histolytica. Exp. Parasitol. 110:244-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakisaka, T., T. Meerlo, J. Matteson, H. Plutner, and W. E. Balch. 2002. Rab-αGDI activity is regulated by a Hsp90 chaperone complex. EMBO J. 21:6125-6135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salminen, A., and P. J. Novick. 1987. A ras-like protein is required for a post-Golgi event in yeast secretion. Cell 49:527-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segev, N., J. Mulholland, and D. Botstein. 1988. The yeast GTP-binding YPT1 protein and a mammalian counterpart are associated with the secretion machinery. Cell 52:915-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singer-Kruger, B., H. Stenmark, A. Dusterhoft, P. Philippsen, J. S. Yoo, D. Gallwitz, and M. Zerial. 1994. Role of three rab5-like GTPases, Ypt51p, Ypt52p, and Ypt53p, in the endocytic and vacuolar protein sorting pathways of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 125:283-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singer-Kruger, B., H. Stenmark, and M. Zerial. 1995. Yeast Ypt51p and mammalian Rab5: counterparts with similar function in the early endocytic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 108:3509-3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stenmark, H., and V. M. Olkkonen. 2001. The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol. 2:REVIEWS3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun, P., H. Yamamoto, S. Suetsugu, H. Miki, T. Takenawa, and T. Endo. 2003. Small GTPase Rah/Rab34 is associated with membrane ruffles and macropinosomes and promotes macropinosome formation. J. Biol. Chem. 278:4063-4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takai, Y., T. Sasaki, and T. Matozaki. 2001. Small GTP-binding proteins. Physiol. Rev. 81:153-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tang, B. L., S. H. Low, H. P. Hauri, and W. Hong. 1995. Segregation of ERGIC53 and the mammalian KDEL receptor upon exit from the 15 degrees C compartment. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 68:398-410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang, B. L., S. H. Wong, X. L. Qi, S. H. Low, and W. Hong. 1993. Molecular cloning, characterization, subcellular localization and dynamics of p23, the mammalian KDEL receptor. J. Cell Biol. 120:325-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsukada, M., and D. Gallwitz. 1996. Isolation and characterization of SYS genes from yeast, multicopy suppressors of the functional loss of the transport GTPase Ypt6p. J. Cell Sci. 109:2471-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]