Abstract

One of the least-explored aspects of cholesterol-enriched domains (rafts) in cells is the coupling between such domains in the external and internal monolayers and its potential to modulate transbilayer signal transduction. Here, we employed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching to study the effects of antibody-mediated patching of influenza hemagglutinin (HA) proteins [raft-resident wild-type HA and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored HA, or the nonraft mutant HA(2A520)] on the lateral diffusion of internal-leaflet raft and nonraft Ras isoforms (H-Ras and K-Ras, respectively). Our studies demonstrate that the clustering of outer-leaflet or transmembrane raft-associated HA proteins (but not their nonraft mutants) retards the lateral diffusion of H-Ras (but not K-Ras), suggesting stabilized interactions of H-Ras with the clusters of raft-associated HA proteins. These modulations were paralleled by specific effects on the activity of H-Ras but not of the nonraft K-Ras. Thus, clustering raft-associated HA proteins facilitated the early step whereby H-Ras is converted to an activated, GTP-loaded state but inhibited the ensuing step of downstream signaling via the Mek/Erk pathway. We propose a model for the modulation of transbilayer signaling by clustering of raft proteins, where external clustering (antibody or ligand mediated) enhances the association of internal-leaflet proteins with the stabilized clusters, promoting either enhancement or inhibition of signaling.

Cholesterol and sphingolipid-enriched domains termed “lipid rafts” were demonstrated in artificial lipid bilayers and proposed to exist in cell membranes (1, 4, 9, 10, 18, 26, 49, 50). In spite of a wealth of studies on the functional importance of interactions with raft-like domains for many cellular processes (reviewed in references 17, 18, 26, 49, 50, and 53), many questions remain concerning the size, lifetime, and even the existence of lipid rafts in live cells (1, 8, 10, 17, 18, 23, 26, 27, 33, 45, 49, 51, 54). The original simplistic view of lipid rafts was as preexisting liquid-ordered domains enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids, into which specific proteins partition preferentially (4, 10, 49). More recent views envision rafts as small and transient cholesterol-dependent assemblies complexed with proteins, where interactions among the specific proteins influence the formation, size, and stability of these structures (1, 17, 44). The differences between these views involve mainly the nature of cholesterol-dependent assemblies in resting cell membranes. The studies presented here focus not on the resting state but rather on effects triggered by the clustering of proteins associated with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies; therefore, we will refer to such assemblies throughout as “rafts,” without implications to a specific model.

Numerous reports provide evidence in support of such domains in both the outer and inner plasma membrane leaflets (7, 18, 26, 44, 50, 53, 55). The coupling between raft-like domains in different membrane leaflets has an intriguing potential for modulating transbilayer signaling; however, this issue has remained largely unexplored. Related studies were conducted mainly in T cells, where external clustering of raft-associated molecules was reported to induce intracellular signaling, interpreted to indicate a role for raft stabilization/growth in signal transduction (9, 20, 21, 37, 45, 53). However, even in these cells, which are characterized by high spatial organization at the immunological synapse, the involvement of lipid rafts in clustering-induced transbilayer signaling was recently questioned (8, 15, 29, 54).

Here, we employed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to study the effects of clustering outer-leaflet and transmembrane influenza hemagglutinin (HA) mutants that differ in raft association on the interactions of Ras isoforms with inner-leaflet raft domains and on Ras signaling. Ras proteins are small GTPases which operate as molecular switches at the inner leaflet and regulate proliferation, differentiation, and cell survival (18, 46). They are highly suitable for these studies, since they provide a series of closely related proteins that are targeted to cholesterol-sensitive domains to different extents, depending on their lipid anchor, hypervariable C-terminal regions, and GTP/GDP loading state (18). The membrane anchors of H-, N-, and K-Ras all have a CAAX S-farnesylation motif, supplemented by one (N-Ras) or two (H-Ras) adjacent S-palmitoyl residues or by a six-lysine polybasic domain (K-Ras) (18). Ras proteins are localized mainly to the plasma membrane but can also be found in endosomes, the endoplasmic reticulum, and the Golgi apparatus, and the distinct locations may affect the activation of specific pathways (5, 6, 32, 42). Biochemical and biophysical studies (FRAP on live cells and electron microscopy cluster analysis) have shown that the affinity of Ras isoforms to cholesterol-sensitive domains is highest for GDP-loaded wild-type (wt) H-Ras, decreases for constitutively active (GTP-loaded) H-Ras(G12V), and is undetectable for either wt or constitutively active K-Ras (35, 39-41). In line with these findings, single-molecule diffusion measurements indicated that activated H-Ras interacts with cholesterol-independent microdomains (31, 34).

We present here a systematic study that compares directly the transbilayer effects of clustering outer-leaflet HA proteins known to reside in raft domains on the biophysical properties of inner-leaflet Ras proteins and on Ras signaling. The results demonstrate the existence of clustering-induced transbilayer interactions between raft-interacting proteins (but not their nonraft counterparts) in the plasma membrane of live cells and their potential to modulate signaling both positively and negatively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

COS-7 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown as previously described (48). Monovalent rabbit tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-Fab′ directed against the HA protein of the X:31 influenza virus strain (anti-X:31 HA) were prepared from immunoglobulin G (IgG) donated by J. M. White (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA) (48). Rabbit TRITC-Fab′ anti-Japan HA (a gift from M. G. Roth, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) was previously described (48). IgG of HC3 mouse monoclonal anti-X:31 HA and of Fc125 anti-Japan HA (directed against HA of the Japan strain) were gifts from J. J. Skehel (National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom) and T. J. Braciale (University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA), respectively. Goat anti-mouse Cy3-IgG was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. Mouse monoclonal IgG against the extracellular domain of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (antibody [Ab]-10) was from NeoMarkers. Rabbit anti-Erk2 (sc-154) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, mouse anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (M8159) was from Sigma, mouse pan-anti-Ras (Ab-3) was from Calbiochem, and peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG were from Dianova. EGF was from R&D Systems. Bovine serum albumin (BSA; fraction V) was from Roche Applied Science.

Plasmids and cell transfection.

The pEGFP-C3 (where EGFP is enhanced green fluorescent protein) expression vectors for GFP-tagged H-Ras(wt), GFP-H-Ras(G12V), GFP-K-Ras(wt), GFP-K-Ras(G12V), and GFP-tH (GFP fused to the C-terminal lipid anchor of H-Ras) have been described previously (35, 39, 41). HA protein expression vectors employed (described in reference 48) include Japan HA(wt) in pSVT7, Japan HA(2A520) (containing a GS-to-AA mutation at positions 520 and 521 in the transmembrane region) (30, 43) in pCB6, and X:31 BHA-PI, comprised of the ectodomain of HA from the X:31 strain fused to the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor addition signal of DAF, in the pEE14 vector; the latter (donated by J. M. White) is the BHA-PI (K/S) chimera described earlier (22). The pGex-2TH vector for bacterial expression of the glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fused Ras binding domain (RBD) of Raf-1, mutated (A85K) to enhance Ras binding (14), was kindly supplied by A. Burgess (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Melbourne, Australia). COS-7 cells growing in 35-mm dishes (with glass coverslips for FRAP studies) were transfected by DEAE-dextran with 0.15 (GFP-Ras constructs) and/or 0.5 (HA constructs) μg of DNA/dish; the DNA was completed to 0.65 μg by empty vector.

FRAP and patch/FRAP.

Cells were taken for FRAP studies 24 h posttransfection. In some control experiments, they were first subjected to cholesterol depletion (18 h) by incubation with 50 μM compactin and 50 μM mevalonate in medium supplemented with 10% lipoprotein-deficient fetal calf serum as previously described (30, 35, 48). Cell surface HA proteins were labeled at 4°C with TRITC-Fab′ or mouse anti-HA IgG followed by cross-linking with Cy3-coupled goat anti-mouse IgG; the labeling/clustering conditions are detailed in the legend to Fig. 1. The cells were then subjected to FRAP studies, measuring either GFP-Ras or HA diffusion (for details, see the legend to Fig. 1). To minimize internalization during the experiment, measurements were at 22°C, replacing samples within 15 min. FRAP experiments were conducted as described earlier (3, 25), using a monitoring argon ion laser beam (1 μW) at 488 nm (for GFP-Ras) or 528.7 nm (for TRITC-Fab′-HA), focused to a Gaussian radius of 0.85 ± 0.02 μm (63× oil immersion objective). A 5 mW pulse (4 to 6 ms) bleached 60 to 75% of the fluorescence in the illuminated region, and fluorescence recovery was followed by the attenuated monitoring beam. The lateral diffusion coefficient (D) and the mobile fraction (Rf) were extracted from the fluorescence recovery curves by nonlinear regression analysis, fitting to the lateral diffusion equation (36). Patch/FRAP studies were performed similarly, except that antibody-mediated patching of a specific HA protein preceded the measurement (47).

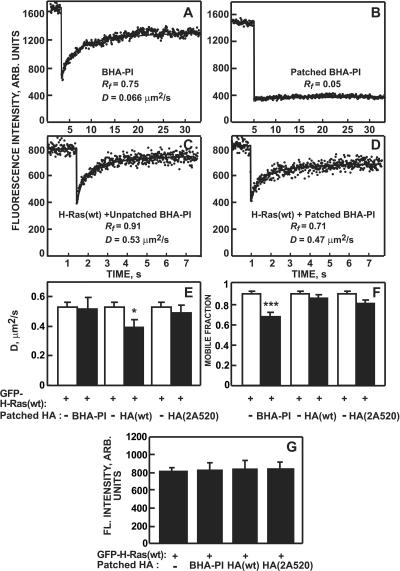

FIG. 1.

Patch/FRAP studies on the effects of clustering HA proteins on the lateral diffusion of GFP-H-Ras(wt). COS-7 cells were cotransfected with expression vectors for GFP-H-Ras(wt) together with the indicated HA mutants. After 24 h, HA was either labeled at 4°C with 100 μg/ml rabbit TRITC-Fab′ fragments to avoid cross-linking [anti-X:31 HA for BHA-PI, anti-Japan HA for HA(wt), and HA(2A520)] or clustered by IgGs (30 μg/ml HC3 mouse anti-X:31 HA or Fc123 mouse anti-Japan HA, followed by 30 μg/ml goat anti-mouse Cy3-IgG). All incubations were in Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with 20 mM HEPES and 2% BSA at pH 7.2. FRAP studies were conducted in the same buffer at 22°C on HA (A and B) or GFP-H-Ras(wt) (C to F). Solid lines (A to D) are the best fit to the lateral diffusion equation (36). (A) Lateral diffusion of unclustered BHA-PI. (B) Effect of clustering on BHA-PI diffusion. Only the Rf value is given, as D could not be determined. Clustered HA(wt) and HA(2A520) were similarly immobile (not shown). (C) Lateral diffusion of GFP-H-Ras(wt) coexpressed with un-cross-linked BHA-PI. (D) Clustering BHA-PI reduces Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt). (E and F) Quantification of the effects of clustering HA proteins on D and Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt). Bars are means ± standard error of the means of 30 to 40 measurements. White bars, HA mutant coexpressed but not cross-linked (designated patched HA; −); black bars, cross-linked HA. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the respective control, with comparisons between samples expressing the same HA protein with and without cross-linking (*, P < 0.01; ***, P < 10−10; Student's two-tailed t test). In the absence of coexpressed HA, the results were similar to those of the un-cross-linked HA-expressing controls. (G) Quantitative measurements of the cell surface levels of GFP-H-Ras(wt). Measurements were done using the point confocal method (see Materials and Methods) on cells treated exactly as described for the FRAP experiments and within up to 15 min at 22°C. The laser beam was focused on defined spots in the focal plane of the plasma membrane remote from the glass slide. Bars are means ± standard error of the means of 100 measurements.

Point confocal measurement of the density of fluorescent proteins at the plasma membrane.

The relative levels of fluorescence-labeled proteins (GFP-Ras isoforms, or EGF receptors labeled with fluorescent antibodies) at the cell surface were quantified by a point confocal measurement of the fluorescence intensity, as described by us earlier (12). The intensity measurement was performed with the FRAP setup using the attenuated, nonbleaching monitoring beam. The measurement employed the 63× objective (Gaussian radius, 0.85 μm). As detailed earlier (12), the fluorescence excited in this well-defined focus of the laser beam passes through a pinhole located at the image plane of the microscope, which is only slightly larger than the beam. This makes it a true one-spot confocal measurement, collecting fluorescence exclusively from the plane of the plasma membrane and passing it to the photomultiplier working in photon-counting mode. The beam was routinely focused on the cell surface remote from the glass slide to which the cells were attached. For each sample and treatment (e.g., cross-linking with anti-HA antibodies and/or incubation with EGF), 100 cells were measured and averaged.

EGF stimulation and immunoblotting.

Transfected cells were grown for 24 h and serum starved for 12 h. The HA proteins were cross-linked at 4°C by a double layer of IgGs or labeled by a single layer of anti-HA TRITC-Fab′ (un-cross-linked controls) as detailed in the legend of Fig. 1. The cells were then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml for 5 min at 37°C), lysed, and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting as described previously (24), loading 30 μg of protein per lane. The blots were labeled with anti-phospho-Erk (dilution of 1:10,000; 12 h at 22°C) followed by peroxidase goat-anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; 1 h at 22°C). The bands were visualized by ECL (Amersham) and quantified by densitometry (Quantity One; Bio-Rad). To probe for total Erk, the blots were acid stripped (24) and reprobed with rabbit anti-Erk (1:1,500) followed by peroxidase-coupled secondary IgG and ECL. A second cycle of reprobing was used to visualize GFP-Ras by pan-anti-Ras (1:2,500) and peroxidase-coupled secondary IgG (1:5,000).

Determination of the levels of GFP-Ras and GFP-Ras-GTP.

Cells were transfected, serum starved, cross-linked with anti-HA antibodies, and stimulated by EGF as described above. Aliquots of the lysates [30 and 60 μg of protein for cells transfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-K-Ras(wt), respectively] were resolved by immunoblotting to determine the total level of the GFP-Ras proteins, using pan-anti-Ras antibodies, peroxidase goat anti-mouse IgG, and ECL as described above. To determine the levels of GFP-Ras-GTP, cell lysates [100 and 400 μg of protein for cells transfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-K-Ras(wt), respectively] were precipitated by glutathione-Sepharose beads coupled to GST-RBD (24). The GST-RBD precipitates were dissolve, and analyzed by immunoblotting with pan-anti-Ras [1:12,500 and 1:2,500 for cells transfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-K-Ras(wt), respectively] to visualize and quantify GFP-Ras-GTP.

RESULTS

Cross-linking raft-interacting HA proteins retards the lateral diffusion of H-Ras(wt) in the inner leaflet.

To study the effects of clustering raft-associated proteins on interactions of signaling proteins embedded in the inner leaflet, we combined antibody-mediated patching of HA proteins with FRAP studies on the lateral diffusion of GFP-tagged Ras proteins (patch/FRAP). The availability of HA mutants (22, 30, 43, 48, 52) and Ras isoforms (35, 39-41) that are targeted to different extents to cholesterol-sensitive domains enables direct comparison between proteins that share similar structural features but differ in raft association. Using the patch/FRAP approach (48), we were able to validate in live cells that HA(wt) (either from the Japan or X:31 strains) and GPI-anchored HA (BHA-PI) interact with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies, while the nonraft HA(2A520) mutant protein (30, 43) does not.

In the patch/FRAP studies, we coexpressed in COS-7 cells one HA mutant together with a GFP-Ras protein. We have previously demonstrated (35) that all the GFP-H-Ras and GFP-K-Ras constructs employed in the current studies retain full biological activity. The HA proteins were externally clustered by a double layer of IgGs in the cold (to avoid internalization); the cells were then shifted to 22°C, and the lateral diffusion of the GFP-Ras protein was measured by FRAP within 15 min. As shown in Fig. 1A and B for BHA-PI and reported previously for all the HA mutants (48), the HA proteins were initially laterally mobile and were effectively immobilized by the clustering. The effects of clustering the various HA proteins on the lateral diffusion coefficient (D) or the mobile fraction (Rf) of GFP-H-Ras(wt) are depicted in Fig. 1C and D (typical curves) and quantified in Fig. 1E and F. Clustering BHA-PI, but not its expression without cross-linking, significantly reduced Rf of H-Ras(wt). On the other hand, clustering HA(wt), which displays transient interactions with clustered rafts (48), reduced D rather than Rf of H-Ras(wt). As we have shown elsewhere (13, 48), both phenomena (reduction in Rf or in D) can occur due to the same basic mechanism of interactions with laterally immobile clusters, and the type of effect depends on the timescale of the FRAP experiment relative to the dissociation/association rates. A reduction in Rf is suggestive of relatively long-lasting interactions with immobile clusters (i.e., complex lifetimes longer than the characteristic fluorescence recovery times in the FRAP experiment), because bleached fluorescent protein molecules associated with the immobilized clusters would not dissociate and exchange appreciably by diffusion with molecules out of the bleached spot during the measurement. A reduction in D is expected for interactions that are transient on this timescale, as each fluorescent molecule [in this case, GFP-H-Ras(wt)] would undergo several association/dissociation cycles during the recovery phase. Importantly, similar IgG-mediated clustering of HA(2A520), which is excluded from raft-like domains (30, 43, 48), had no effect on H-Ras(wt) diffusion; this demonstrates that the effects of the IgG-mediated clustering on H-Ras(wt) lateral diffusion are not simply due to cross-linking but depend on the ability of the clustered HA protein to interact with raft-like assemblies.

Besides direct interactions with the HA clusters, an alternative mechanism that could reduce Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt) following cross-linking of BHA-PI is entrapment of part of the GFP-H-Ras population in submembrane endocytic vesicles, accompanied by a reduction in the cell surface level of GFP-H-Ras due to endocytosis. Although only little internalization and recycling are likely to occur during the short incubation at 22°C in the FRAP studies (less than 15 min), we validated that the cell surface expression levels of GFP-H-Ras(wt) were not significantly affected by the expression of any of the HA proteins or the various cross-linking conditions (Fig. 1G). These levels were measured by the point confocal method described by us earlier (12) (see Materials and Methods), which employs the FRAP setup under nonbleaching conditions to quantify the fluorescence intensity from a defined small spot focused on the plasma membrane. We conclude that clustering of raft-resident (but not nonraft) HA proteins, including BHA-PI which resides in the outer leaflet, can modulate the lateral diffusion of the raft-interacting H-Ras(wt) in the inner leaflet.

Cross-linking GPI-anchored HA selectively restricts the mobility of raft-interacting Ras proteins.

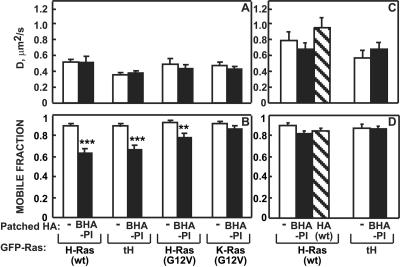

The strongest effect on GFP-H-Ras(wt) diffusion was induced by clustering the GPI-anchored BHA-PI protein. To further characterize the interactions between raft-resident proteins in the outer and inner leaflets, we investigated the effects of clustering BHA-PI on the lateral diffusion of a series of GFP-Ras proteins that differ in their association with cholesterol-sensitive domains (35, 39-41). This provides direct internal controls (by comparison with proteins sharing a similar structure but lacking interactions with raft-like assemblies) without the necessity to rely on treatments that modulate membrane organization or lipid composition. GFP-tH, which contains only the C-terminal lipid anchor of H-Ras and was shown to be a raft-resident protein (39-41), exhibited a reduction in Rf following BHA-PI clustering similar to GFP-H-Ras(wt) (Fig. 2A and B). On the other hand, Rf of constitutively active GFP-H-Ras(G12V), whose interactions with raft domains are weaker (35, 39, 40), was affected to a lower extent (Fig. 2B). Importantly, no effect was detected on the lateral diffusion of GFP-K-Ras(G12V), in keeping with its exclusive distribution in nonraft regions (35, 39, 40).

FIG. 2.

Clustering BHA-PI reduces Rf of raft-interacting Ras isoforms. FRAP experiments were performed as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Bars are means ± standard error of the means of 30 to 60 measurements. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the respective un-cross-linked control (**, P < 10−4; ***, P < 10−10). The reduction in Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH upon cross-linking BHA-PI was significantly higher than for GFP-H-Ras(G12V) (P < 0.02). (A and B) Lateral diffusion of GFP-Ras isoforms in the presence (black bars) or absence (white bars) of coexpressed IgG-cross-linked BHA-PI. Control experiments where BHA-PI was labeled with TRITC-Fab′ (no cross-linking) yielded results similar to the control (−). (C and D) Cholesterol depletion reverses the effects of clustering BHA-PI on the lateral diffusion of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH. For each condition (with and without coexpression of BHA-PI and with and without IgG-mediated clustering), point confocal measurements of the cell surface levels of the GFP-Ras proteins were conducted exactly as described in the legend of Fig. 1G; no significant differences due to either expression of BHA-PI or its cross-linking were observed (data not shown).

These findings, together with the results depicted in Fig. 1, strongly suggest that the modulation of the lateral diffusion of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH by external clustering of HA proteins depends on interactions with raft-like assemblies. This suggestion stems from the selectivity of the effects observed regarding both the clustered HA protein and the GFP-Ras protein whose diffusion was measured; notably, this selectivity is detected with proteins that, aside from the differences in raft association, are structurally related. Thus, the effects on the diffusion of Ras proteins were exerted only by clustering of those HA proteins known to interact with raft-like assemblies, and the Ras isoforms that responded to this modulation were only those interacting with such domains. As an additional test for this notion, we examined the effects of cholesterol depletion on the clustering-induced retardation in the lateral diffusion of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH (Fig. 2C and D). It should be noted that cholesterol depletion may have additional effects on intracellular transport and signaling aside from disrupting cholesterol-dependent assemblies; yet if the effects mediated by HA clustering on Ras mobility depend on interactions with such assemblies, they should be reversed by the disruption of raft-like structures. Cholesterol was depleted using metabolic inhibition by compactin in the presence of a low level of mevalonate to enable farnesylation (30, 35, 48); this treatment was preferred over methyl-β-cyclodextrin, as the latter inhibits the lateral diffusion of membrane proteins without dependence on raft association (16, 35, 47). The metabolic inhibition reduced the membrane cholesterol content by 30 to 33%, a level shown to be sufficient to release both HA and H-Ras proteins from raft-like domains (35, 41, 47, 48). Accordingly, the cholesterol depletion increased D of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH (Fig. 2C). This treatment completely abolished the effects of clustering BHA-PI or HA(wt) on the lateral diffusion of both GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH (Fig. 2C and D).

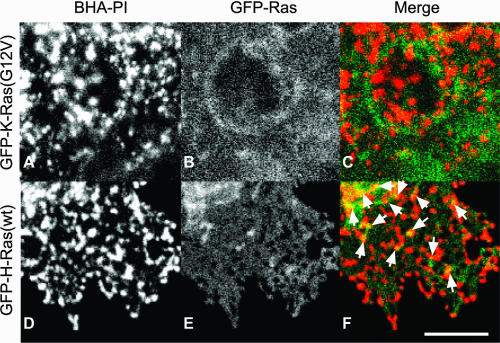

The reduction in Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH upon clustering of BHA-PI suggests stabilized interactions of these inner-leaflet proteins with the clusters of the GPI-anchored HA. We therefore employed confocal microscopy to examine the recruitment of GFP-Ras isoforms to these clusters. BHA-PI was coexpressed with a GFP-Ras protein and clustered at 4°C by a double layer of IgGs as described for the FRAP experiments (Fig. 1). The cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde and examined by confocal microscopy, focusing on the cell surface remote from the glass slide to which the cells are attached. As shown in Fig. 3, the IgG-clustered BHA-PI was concentrated in visible fluorescent patches. Although the colocalization of GFP-H-Ras(wt) (or GFP-tH) with the BHA-PI patches was mild (Fig. 3, frames D to F and arrows in F), it was specific, as shown by the completely diffuse fluorescence of GFP-K-Ras(G12V) under the same conditions (Fig. 3, frames A to C). The lack of strong colocalization prompted us to consider the possibility that the interactions of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH with the BHA-PI clusters are stable for the short duration of the FRAP experiments employed (up to a few seconds) but not on longer timescales. If the dissociation rate of, e.g., GFP-H-Ras(wt) from the clusters is slow enough such that only a small population dissociates from the clusters during the FRAP measurement, the major effect would be to reduce Rf. However, if the timescale is considerably increased, there may be sufficient time for the entire GFP-H-Ras(wt) population to dissociate from the clusters, allowing the mobile fraction to return to the original value. Indeed, when the timescale of the FRAP experiment was increased over fivefold (from 7.68 s to 40.96 s for a complete recovery curve), Rf of both GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH in cells with clustered BHA-PI increased from, from initial Rf 0.68 to 0.70 (Fig. 1 and 2), to 0.92 ± 0.02 (n = 35 cells for each protein), similar to their Rf in the absence of BHA-PI clustering (0.90 to 0.91). This demonstrates that the association of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH with the BHA-PI clusters is, indeed, transient on longer timescales, and the difference between the effects of clustering HA(wt) and BHA-PI is quantitative rather than qualitative (a higher stabilization of the interactions with the clusters in the latter case).

FIG. 3.

Effects of clustering BHA-PI on the distribution of GFP-Ras isoforms visualized by confocal microscopy. Cells were cotransfected with BHA-PI together with either GFP-H-Ras(wt), GFP-tH, or GFP-K-Ras(G12V). BHA-PI was clustered at 4°C by IgGs (HC3 mouse anti-X:31 HA followed by goat anti-mouse Cy3-IgG) as described in the legend of Fig. 1. After washing, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (15 min at 4°C to ensure no endocytosis, followed by 15 min at 22°C) and mounted with Prolong Antifade (Molecular Probes). Fluorescence images were collected on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. The images shown are at the focus of the cell surface remote from the glass slide. Bar, 5 μm. Some colocalization of GFP fluorescence with the BHA-PI clusters is seen for GFP-H-Ras(wt) (D to F; see arrows) and for GFP-tH (not shown) but not for GFP-K-Ras(G12V) (A to C).

Clustering raft-resident HA proteins inhibits H-Ras(wt) downstream signaling via the Mek/Erk pathway.

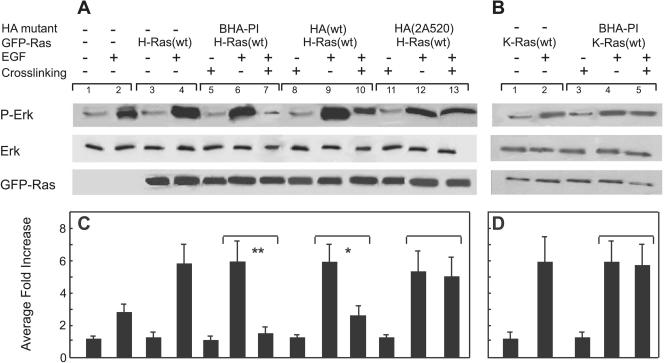

Recent studies have suggested that release of activated H-Ras from raft-like domains is required for efficient activation of the Mek/Erk pathway (18, 39), although this view was recently challenged (32). We therefore investigated the effects of clustering the various HA mutants on Erk activation following stimulation of H-Ras(wt) or K-Ras(wt) by EGF (Fig. 4). Cells were cotransfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) or GFP-K-Ras(wt) together with one of the HA mutants. After serum starvation, they were subjected to clustering by IgGs (or labeling with Fab′), followed by stimulation with EGF. Western blotting was used to determine the levels of phospho-Erk (a measure for Erk activation), total Erk, and GFP-Ras. As shown in a representative experiment (Fig. 4A) and quantified by averaging several experiments (Fig. 4C), EGF stimulated Erk phosphorylation in untransfected cells (reflecting endogenous Ras activity), an effect that was significantly augmented following transfection with GFP-H-Ras(wt) (Fig., 4A, lanes 1 to 4). Expression of any one of the HA proteins without additional treatments (clustering or EGF addition) had no effect on the phospho-Erk levels, which remained similar to those in untransfected, unstimulated cells (not shown). IgG-mediated clustering of any of the HA proteins, including BHA-PI, did not alter the phospho-Erk levels (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 5, 8, and 11 to lane 3), demonstrating that HA clustering by itself neither stimulates nor inhibits Erk activation. Moreover, expression of an HA protein did not interfere with the ability of EGF to induce Erk phosphorylation (Fig. 4A, lanes 4, 6, 9, and 12). Importantly, the clustering of HA proteins had marked effects on the ability of EGF to stimulate Erk phosphorylation in cells transfected with H-Ras(wt), and these effects showed a clear dependence on the tendency of the cross-linked HA protein to associate with raft-like assemblies. Thus, clustering BHA-PI strongly inhibited the EGF-stimulated elevation in phospho-Erk (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 7 and 6), while a milder but significant inhibition was induced by clustering HA(wt) (lane 10). On the other hand, cross-linking of the nonraft HA(2A520) protein had no effect on EGF-mediated Erk phosphorylation (Fig. 4A, lanes 12 and 13). An additional control was provided by testing the effects of BHA-PI clustering on EGF-stimulated Erk phosphorylation in cells transfected with GFP-K-Ras(wt), which does not interact with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies (Fig. 3B and D). Accordingly, clustering of BHA-PI had no significant effect on the levels of phospho-Erk induced by EGF in these cells (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 2, 4, and 5). A fully analogous pattern of inhibition (data not shown) was observed in similar experiments on EGF-induced Mek phosphorylation, probing phospho-Mek by anti-Mek1/2(Ser217/221) (Cell Signaling). Thus, in cells transfected with H-Ras(wt), the highest inhibition was mediated by clustering BHA-PI, while clustering HA(2A520) had no effect; in cells transfected with K-Ras(wt), clustering BHA-PI had no effect. Our findings are in accord with a study (39) where H-Ras(G12V) and a mutant derived from it that strongly partitions into cholesterol-dependent domains (HΔhvrG12V) were compared for their ability to activate Raf, Mek, and Erk. Their results indicate reduced ability to activate all three proteins of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by the raft-resident mutant. Moreover, because EGF stimulation may alter the cycling rates of the EGF receptors and/or Ras proteins through endocytic pathways, we monitored the cell surface expression levels of these proteins under the experimental conditions employed for the experiments shown in Fig. 4. The results (Fig. 5) demonstrate that the levels of the EGF receptors and GFP-H-Ras (or K-Ras) in the plasma membrane before and after EGF stimulation were not affected by IgG cross-linking of BHA-PI proteins (Fig. 5). These results suggest that clustering of raft-interacting HA proteins interferes with the ability of the raft-associated H-Ras(wt), but not the nonraft K-Ras(wt), to activate Erk.

FIG. 4.

EGF-stimulated Erk phosphorylation is inhibited by clustering of raft-resident HA proteins in cells transfected with H-Ras(wt) but not with K-Ras(wt). COS-7 cells were cotransfected with expression vectors for GFP-H-Ras(wt) or GFP-K-Ras(wt) alone or together with expression vectors for the indicated HA proteins. After 24 h, they were incubated (12 h) in serum-free medium and subjected (or not) to IgG clustering of the HA proteins as described in the legend of Fig. 1. After washing, the cells were stimulated by EGF (100 ng/ml, 5 min, 37°C), lysed, and subjected to immunoblotting with anti-phospho-Erk (P-Erk), anti-Erk (to determine total Erk), and pan-anti-Ras antibodies (to determine GFP-Ras, identified by its higher molecular weight) as described in Materials and Methods. Visualization by ECL was followed by densitometric analysis. (A and B) Immunoblots of typical experiments on cells transfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) or GFP-K-Ras(wt), respectively. (C and D) Quantification of the increase in Erk phosphorylation in three to six experiments similar to those shown in the upper panels, calibrating the P-Erk according to the total Erk levels. Data are shown as the relative increase in P-Erk (means ± standard error of the means) relative to the P-Erk level in untransfected, unstimulated cells (lane 1 in panel A); transfection with any of the HA proteins without additional treatments yielded P-Erk levels similar to those shown in lane 1 (not shown). Asterisks indicate significant differences after EGF stimulation between cells expressing a specific HA protein without clustering versus the same cells after IgG-mediated HA cross-linking (brackets; *, P < 0.01; **, P < 0.001).

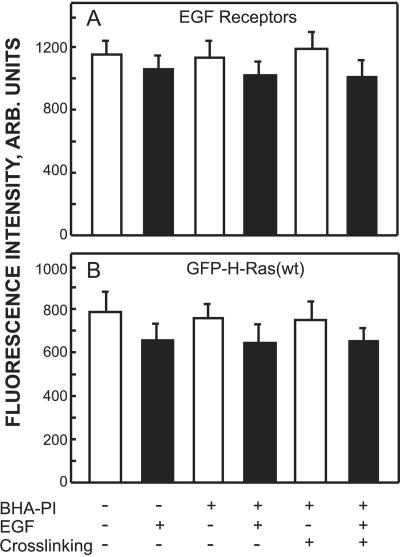

FIG. 5.

The cell surface levels of EGF receptors and GFP-Ras proteins are not altered by clustering of GPI-anchored HA. Cells were transfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) or GFP-K-Ras(wt) alone or together with BHA-PI, serum starved, and subjected (or not) to IgG clustering of BHA-PI at 4°C as described in the legend of Fig. 3. Some samples were fixed at this point with 4% paraformaldehyde under nonpermeabilizing conditions as in the experiment shown in Fig. 3, and their surface EGF receptors were labeled by fluorescent antibodies (see below) to measure the surface levels in the absence of EGF stimulation (blank bars). Other samples were subjected to EGF stimulation (100 ng/ml for 5 min at 37°C), returned to 4°C, fixed as above, and immunolabeled for the EGF receptors (black bars). In both cases, fixation was followed by quenching with 50 mM glycine in phosphate-buffered saline, and the EGF receptors were labeled by 10 μg/ml Ab-10 followed by 30 μg/ml goat anti-mouse Cy3-IgG in phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 2% BSA. The labeled cells were subjected to quantitative measurement of the cell surface levels of the EGF receptors or GFP-H-Ras(wt) by the point confocal method (Materials and Methods), using the appropriate laser line (528.7 nm and 488 nm for Cy3 and GFP fluorescence, respectively) with selective band pass emission filters. The laser beam was focused on defined spots in the focal plane of the plasma membrane. Bars are means ± standard error of the means of 100 measurements. (A) EGF receptors. (B) GFP-H-Ras(wt). GFP-K-Ras(wt) gave similar results (not shown).

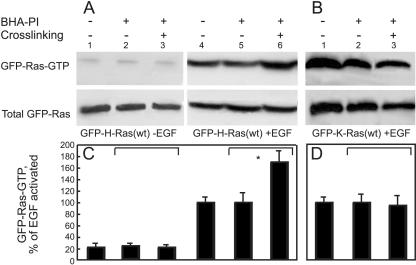

To explore whether the clustering-mediated inhibition in H-Ras signaling occurs already at the stage of Ras activation (i.e., Ras-GTP formation), we employed glutathione-Sepharose beads coupled to GST-RBD to pull down Ras-GTP isoforms from unstimulated or EGF-stimulated cells cotransfected with a GFP-Ras(wt) isoform and BHA-PI, with or without HA clustering. The GTP-loaded GFP-H-Ras or GFP-K-Ras from the transfected cells was identified by Western blotting (Fig. 6). As expected, clustering BHA-PI had no effect on the EGF-mediated conversion of GFP-K-Ras(wt), which is mainly GDP loaded, to a GTP-loaded form (Fig. 6B and D, compare lanes 2 and 3). However, BHA-PI clustering markedly enhanced the ability of EGF to induce GTP-loading of GFP-H-Ras(wt) (Fig. 6A and C, lanes 5 and 6), an effect opposite to the inhibition of Erk phosphorylation. This effect is not simply due to BHA-PI expression (Fig. 6A and C, compare lane 4 with 5 and lane 1 with 2) and is not induced by cross-linking BHA-PI in the absence of EGF stimulation (Fig. 6A and C, compare lanes 2 and 3). We conclude that clustering the GPI-anchored BHA-PI, which leads to enhanced association of H-Ras-GDP with raft-like assemblies (Fig. 1 and 2), has different effects on specific steps in H-Ras signaling; while the first step of converting H-Ras-GDP-to a GTP-bound form is enhanced, the ensuing downstream signaling leading to Erk phosphorylation is inhibited.

FIG. 6.

Clustering BHA-PI enhances the level of GTP-bound GFP-H-Ras but not GFP-K-Ras following EGF stimulation. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) or GFP-K-Ras(wt) together with BHA-PI (or empty vector; control). They were subjected to serum starvation, IgG clustering, and EGF stimulation as described in the legend of Fig. 4. Aliquots of the lysates [30 μg of protein for GFP-H-Ras(wt); 60 μg of protein for GFP-K-Ras(wt)] were immunoblotted with pan-anti-Ras (lower panels) to determine total GFP-Ras. To determine the level of GTP-bound activated GFP-Ras proteins, aliquots (100 and 400 μg for GFP-H-Ras and GFP-K-Ras, respectively) were subjected to the GST-RBD pull-down assay (see Materials and Methods), followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotting with pan-anti-Ras. (A and B) Representative blots of experiments on cells transfected with GFP-H-Ras(wt) or GFP-K-Ras(wt), respectively. (C and D) Quantification of the levels of GTP-loaded GFP-Ras proteins. Results are means ± standard error of the means of three experiments. The amounts of GFP-Ras-GTP were calibrated relative to total GFP-Ras for each lane. In panel C, data are presented as percent GFP-H-Ras-GTP, taking as 100% the calibrated levels of GFP-H-Ras-GTP after EGF stimulation in cells transfected only with GFP-H-Ras(wt) (lane 4). In panel D, the equivalent sample of EGF-stimulated cells expressing GFP-K-Ras(wt) (lane 1) was taken as 100%. Asterisks indicate significant differences between cells expressing BHA-PI without cross-linking versus the same cells after HA clustering (brackets; *, P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Many biological functions were attributed to interactions of receptors and signaling proteins with cholesterol-sensitive domains, commonly termed lipid rafts (1, 4, 9, 18, 26, 49, 50, 53). However, the existence of such domains in living cells has recently been debated (1, 8, 10, 17, 26, 33, 44, 49, 53, 54). Cholesterol-sensitive assemblies were suggested to exist in both the external and internal leaflets of the plasma membrane (7, 18, 26, 44, 50, 53, 55), but the mechanisms that couple them to enable transbilayer effects on signaling remained elusive. In the current report, we employed patch/FRAP studies on the lateral diffusion of GFP-Ras isoforms, combined with functional studies on Ras signaling, to explore concomitant effects of external cross-linking of raft-associated HA proteins on these biophysical and biochemical parameters. Our studies demonstrate that clustering raft-interacting HA proteins (but not their nonraft variants) at the outer monolayer can either enhance or inhibit specific signaling steps at the inner leaflet. We propose a model that can give rise to such modulations by stabilization of raft interactions through clustering and that suggests a mechanism whereby dynamic interactions with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies facilitate H-Ras signaling via the Mek/Erk pathway.

To enable systematic studies on the potential transbilayer coupling between raft-associated proteins, we employed two series of proteins (HA and Ras variants) that differ in their affinity to raft-like domains but otherwise share the same protein background. This provides internal controls by enabling direct comparison between the effects of raft and nonraft variants of the same proteins, without the need for treatments that modulate membrane organization or lipid composition. The D values of un-cross-linked BHA-PI (Fig. 1), HA(wt), and HA(2A520) (48) are at the high end reported for transmembrane proteins (11, 19). However, as shown in Fig. 1 and in accord with previous reports (23, 35, 48), these D values are lower than that of GFP-H-Ras(wt). The absence of both the transmembrane and cytosolic domains in the GPI-anchored BHA-PI and the lack of signals for interaction with intracellular structures and the endocytic apparatus in the short cytoplasmic tail of HA(wt) or HA(2A520) (13, 28, 48) leave the large extracellular region shared by the trimeric HA proteins as the most likely source for retarding their mobility, possibly by interactions with the extracellular matrix and/or other membrane proteins. The difference between the D values of the raft-interacting HA proteins [BHA-PI or HA(wt)] and GFP-H-Ras(wt) in untreated cells is not necessarily a direct measure of their residency (or lack of residency) in separate raft-like assemblies; an alternative possibility is that they have different affinities for cholesterol-sensitive assemblies and interact with them transiently with different dynamics. A higher affinity of BHA-PI and HA(wt) to detergent-resistant membranes compared to H-Ras(wt) is suggested by their different resistance to extraction with cold Triton X-100 [1% detergent for the HA proteins and 0.125% for H-Ras(wt)] (2, 39).

Clustering of GPI-anchored proteins was proposed to stabilize and perhaps induce growth of raft domains (49). Importantly, IgG cross-linking results in lateral immobilization of the HA-containing clusters (Fig. 1), creating favorable conditions for detecting effects on the lateral diffusion of coexpressed GFP-Ras proteins. As discussed in Results, slow dissociation (low level of exchange on the FRAP timescale) of a GFP-Ras protein from the immobile patches would reduce its Rf value, while transient interactions on the FRAP timescale would reduce its D value. The patch/FRAP studies (Fig. 1 and 2) demonstrate a clear correlation between the effects of external clustering of HA proteins on the lateral diffusion of GFP-Ras proteins and the tendency of both the cross-linked (HA series) and internal-leaflet (GFP-Ras series) proteins to associate with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies. The experiments contain dual internal controls for the dependence of the biophysical effects measured on interactions with clusters of raft-interacting proteins; these controls are provided by the direct comparison between proteins that differ in raft association but share structural similarities. Importantly, they do not depend on the use of treatments that interfere with lipid composition and/or membrane organization and therefore may have additional effects. In these studies, the lateral diffusion of GFP-H-Ras-(wt) was affected by clustering the raft-interacting HA proteins BHA-PI (strongest effect) and HA(wt), while clustering the nonraft HA(2A520) had no effect (Fig. 1). Furthermore, clustering BHA-PI (Fig. 2A and B) had a differential effect on the lateral diffusion of GFP-Ras proteins, in correlation with their raft association. It retarded the diffusion of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH, which were reported to interact with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies, but not of GFP-K-Ras(G12V), which does not interact with such domains (39-41). Constitutively active GFP-H-Ras(G12V), which interacts only weakly with cholesterol-dependent assemblies (35, 38, 40), was accordingly affected to a lower degree (Fig. 2B). These findings are in line with electron microscopy cluster analysis studies, which reported reorganization and partial colocalization of GFP-tH aggregates upon cross-linking GFP-GPI (40). A further support for the dependence of the effects measured on interactions with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies is provided by the loss of the effects of BHA-PI clustering on the diffusion of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH following cholesterol depletion (Fig. 2C and D).

FRAP studies conducted on a relatively fast timescale (Fig. 1 and 2) showed a reduction in Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH upon cross-linking BHA-PI, suggesting that the dissociation rate of these proteins from sites/assemblies associated with the immobile clusters is slower than their characteristic fluorescence recovery times (around 300 ms) (Fig. 1). However, their interactions with the BHA-PI clusters are transient at longer periods, as demonstrated by their partial, mild colocalization with BHA-PI clusters (Fig. 3) and by the return of the lower Rf values of these proteins to the original high values in spite of BHA-PI clustering upon a fivefold extension of the FRAP timescale (see Results). The latter findings also rule out the possibility that the reduction in Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt) and GFP-tH following BHA-PI clustering in the short-timescale FRAP experiment is due to entrapment of GFP-Ras molecules in endocytic vesicles, since such entrapped proteins would not have sufficient time to recycle back to the plasma membrane and recover by lateral diffusion (the extended FRAP timescale was 41 s at 22°C). This conclusion is in line with the lack of effect of BHA-PI (or other HA proteins) expression or clustering on the cell surface levels of the GFP-Ras proteins (Fig. 1 and 2).

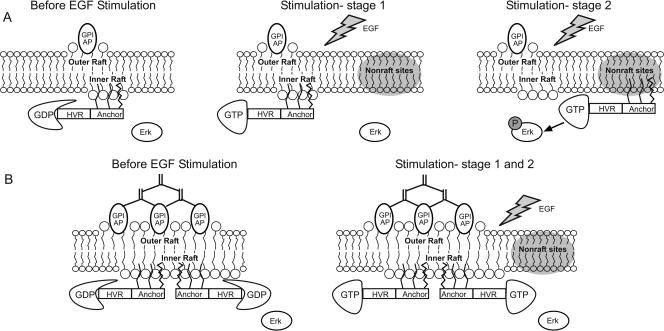

The effects of clustering HA proteins on the interactions of H-Ras(wt) with inner-leaflet rafts were mirrored by their ability to modulate EGF-stimulated H-Ras signaling at two distinct steps, enhancing the first step [conversion of GDP-loaded H-Ras(wt) to a GTP-loaded state] while inhibiting the ensuing downstream signaling (Erk phosphorylation) (Fig. 4 and 6). However, it is important to note that while clustering BHA-PI induced only a mild reduction in Rf of GFP-H-Ras(wt) (Fig. 1F and 2B), the resulting inhibition of Erk phosphorylation was much stronger, even on the background of endogenous Ras that includes isoforms (e.g., K-Ras) insensitive to HA clustering (Fig. 4). This phenomenon may involve the transient nature of the interactions of H-Ras with the BHA-PI clusters, demonstrated by the increase in Rf on the longer timescale. Transient interactions (repetitive entry/exit) of H-Ras with raft-like assemblies acting as “catalytic centers” for activating H-Ras molecules, which then leave to induce downstream signaling, may lead to strong inhibition of the downstream signaling under conditions that stabilize the interactions with these assemblies (e.g., BHA-PI cross-linking). This is due to inhibition of the dissociation rate of activated H-Ras from the clusters. We propose (Fig. 7) that association with such assemblies facilitates H-Ras activation (GTP loading) by EGF, but the ensuing departure of H-Ras-GTP is required for its interaction with downstream signaling components associated with nonraft sites. Indeed, constitutively active GFP-H-Ras(G12V), which is GTP loaded, exhibits significant interactions with BHA-PI clusters, but as predicted by the model these interactions are weaker than those of the GDP-loaded GFP-H-Ras(wt) (Fig. 2B). The model (Fig. 7) suggests that clustering raft-associated proteins in the outer leaflet stabilizes their interactions with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies in the inner leaflet. This, in turn, stabilizes the association of inner-leaflet proteins such as GDP-loaded H-Ras(wt) with these sites; the enhanced association facilitates its EGF-stimulated conversion to a GTP-loaded state but retards the dissociation of the activated H-Ras-GTP from these assemblies, leading to inhibition of its downstream signaling via the Mek/Erk pathway. Importantly, both the EGF-enhanced GTP-loading of H-Ras and the inhibition of Erk phosphorylation following the clustering of HA proteins [BHA-PI and HA(wt)] occurred in spite of the lack of effect of the clustering on the cell surface levels of the EGF receptors or GFP-H-Ras (Fig. 5). A prediction of this model is that the inhibition in the downstream signaling should be proportional to the extent of the clustering-mediated inhibition of the association/dissociation kinetics of H-Ras from the clusters. Accordingly, clustering of HA(wt), which retards the dissociation of GFP-H-Ras(wt) from the immobile clusters to a lower degree than BHA-PI clustering (reduction in D already at the short timescale) (Fig. 1E), inhibited EGF-stimulated H-Ras downstream signaling to a lesser extent (Fig. 4A and C).

FIG. 7.

A model for transbilayer modulation of H-Ras signaling in the inner leaflet by clustering outer-leaflet raft-associated proteins. (A) No external clustering. (B) Effects of clustering outer-leaflet raft proteins. In panel A, unactivated GDP-loaded H-Ras(wt) interacts dynamically with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies in the inner leaflet. Stimulation by EGF is shown in two steps. At stage 1, H-Ras is converted to an activated GTP-loaded state; this step is facilitated by association with inner-leaflet rafts, which can be viewed as “catalytic centers” that catalyze H-Ras activation. At stage 2, the activated H-Ras-GTP leaves to associate with other sites or scaffolds designated as “nonraft” sites, which facilitate downstream signaling (in this case, phospho-Erk formation). In panel B, GPI-anchored proteins (GPI-AP) residing in the outer leaflet are clustered (by IgGs as shown in the scheme or by ligands) prior to stimulation by EGF. The clustering leads to stabilization and possibly growth of raft-like domains in the outer leaflet. This enhances the loose interactions of inner-leaflet rafts with the outer raft clusters, possibly bridged by both lipid interdigitation and mutual affinity to raft-interacting transmembrane proteins (not shown). As a result, the association of H-Ras with these sites is stabilized; the ensuing inhibition of the association/dissociation kinetics enhances the first stage (GTP-loading) but inhibits the transfer of activated H-Ras-GTP to the nonraft sites which facilitate Erk phosphorylation. HVR, hypervariable region.

Our results and model are in excellent agreement with biochemical and electron microscopy studies, which suggested that release of activated H-Ras from rafts is required for efficient activation of Raf (39, 40). The notion that GTP-loading of H-Ras shifts it toward nonraft sites is supported by reports employing different biophysical methods, which indicated that H-Ras-GTP but not H-Ras-GDP interacts preferentially with nonraft assemblies (31, 34, 35, 40). In contrast to these reports and to the results presented here, a recent study argued against a role for nonraft localization of activated H-Ras in downstream signaling (32). However, this study was based on chimeric constructs artificially targeted to produce stable association with raft domains; alteration of the kinetics of these interactions may have critical effects on signaling efficiency. Moreover, the membrane anchoring signals of these chimeras were introduced at the N terminus of H-Ras, and the inverse topology may also interfere with the normal interactions of H-Ras with protein scaffolds involved in signaling. In addition, the dependence of H-Ras activation on raft association could not be determined in this study, due to cross-reactivity between the raft- and nonraft-targeted dominant negative H-Ras chimeras employed for this purpose.

The basic features of the model presented in Fig. 7 can give rise to a general mechanism for transbilayer modulation of intracellular signaling events. Related mechanisms were proposed for the triggering of T-cell (and B-cell) signaling by clustering external-leaflet proteins/lipids or transmembrane receptors (9, 20, 21, 27, 45, 51, 53). In this context, it should be noted that although there is a general agreement on the involvement of membrane subdomains in T-cell signaling, the mechanisms involved are controversial. Two recent papers (8, 54) employing Jurkat T cells reported that although clustering induced signaling in these cells, it was mediated also by cross-linking nonraft proteins or artificial lipid-linked proteins. This situation differs from the findings in the current study and may reflect the more permanent nature of the immunological synapses that exist in these cells and enable a battery of protein-protein interactions. Other factors that may contribute to the general effects of cross-linking in one of these reports (54) are the artificial nature and high surface density of the cross-linked probes externally incorporated into the cell membrane (lipid-conjugated biotin derivatives clustered by streptavidin). Unlike the lack of dependence on interactions with raft-like assemblies in these studies, we have demonstrated in the current work selective modulatory effects induced by clustering HA proteins that specifically interact with raft-like assemblies. These effects can propagate to the internal leaflet and affect H-Ras raft interactions and signaling. In this system, there is a clear dependence of the effects on the association of both the external cross-linked proteins and the inner-leaflet proteins with cholesterol-sensitive assemblies. Analogous mechanisms may operate also in other cell types and with other stimulatory signals. Thus, specific ligands can effectively cross-link raft-interacting receptors at the cell surface. The resulting stabilization of inner-leaflet raft-like assemblies can then induce either stimulatory or inhibitory effects on signaling molecules interacting with these domains.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an award from the Jacqueline Seroussi Memorial Foundation for Cancer Research (to Y.I.H.). Y.I.H. is an incumbent of the Zalman Weinberg Chair in Cell Biology.

We thank T. J. Braciale, A. Burgess, M. G. Roth, J. J. Skehel, and J. M. White for reagents. Helpful comments and discussions with Barak Rotblat are gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, R. G., and K. Jacobson. 2002. A role for lipid shells in targeting proteins to caveolae, rafts, and other lipid domains. Science 296:1821-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong, R. T., A. S. Kushnir, and J. M. White. 2000. The transmembrane domain of influenza hemagglutinin exhibits a stringent length requirement to support the hemifusion to fusion transition. J. Cell Biol. 151:425-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelrod, D., D. E. Koppel, J. Schlessinger, E. L. Elson, and W. W. Webb. 1976. Mobility measurement by analysis of fluorescence photobleaching recovery kinetics. Biophys. J. 16:1055-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, D. A., and E. London. 2000. Structure and function of sphingolipid-and cholesterol-rich membrane rafts. J. Biol. Chem. 275:17221-17224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu, V. K., T. Bivona, A. Hach, J. B. Sajous, J. Silletti, H. Wiener, R. L. Johnson II, A. D. Cox, and M. R. Philips. 2002. Ras signalling on the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:343-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choy, E., V. K. Chiu, J. Silletti, M. Feoktistov, T. Morimoto, D. Michaelson, I. E. Ivanov, and M. R. Philips. 1999. Endomembrane trafficking of Ras: the CAAX motif targets proteins to the ER and Golgi. Cell 98:69-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrich, C., B. Yang, T. Fujiwara, A. Kusumi, and K. Jacobson. 2002. Relationship of lipid rafts to transient confinement zones detected by single particle tracking. Biophys. J. 82:274-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douglass, A. D., and R. D. Vale. 2005. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell 121:937-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dykstra, M., A. Cherukuri, H. W. Sohn, S. J. Tzeng, and S. K. Pierce. 2003. Location is everything: lipid rafts and immune cell signaling. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21:457-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edidin, M. 2003. The state of lipid rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32:257-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edidin, M. 1992. Translational diffusion of membrane proteins, p. 539-572. In P. Yeagle (ed.), The structure of biological membranes. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 12.Ehrlich, M., A. Shmuely, and Y. I. Henis. 2001. A single internalization signal from the di-leucine family is critical for constitutive endocytosis of the type II TGF-β receptor. J. Cell Sci. 114:1777-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fire, E., O. Gutman, M. G. Roth, and Y. I. Henis. 1995. Dynamic or stable interactions of influenza hemagglutinin mutants with coated pits: dependence on the internalization signal but not on aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21075-21081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fridman, M., H. Maruta, J. Gonez, F. Walker, H. Treutlein, J. Zeng, and A. Burgess. 2000. Point mutants of c-raf-1 RBD with elevated binding to v-Ha-Ras. J. Biol. Chem. 275:30363-30371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glebov, O. O., and B. J. Nichols. 2004. Lipid raft proteins have a random distribution during localized activation of the T-cell receptor. Nat. Cell Biol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Goodwin, J. S., K. R. Drake, C. L. Remmert, and A. K. Kenworthy. 2005. Ras diffusion is sensitive to plasma membrane viscosity. Biophys. J. 89:1398-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock, J. F. 2006. Lipid rafts: contentious only from simplistic standpoints. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:456-462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hancock, J. F., and R. G. Parton. 2005. Ras plasma membrane signalling platforms. Biochem. J. 389:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henis, Y. I. 1993. Lateral and rotational diffusion in biological membranes, p. 279-340. In M. Shinitzki (ed.), Biomembranes: physical aspects, vol. 1. VCH Publishers, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ike, H., A. Kosugi, A. Kato, R. Iino, H. Hirano, T. Fujiwara, K. Ritchie, and A. Kusumi. 2003. Mechanism of Lck recruitment to the T-cell receptor cluster as studied by single-molecule-fluorescence video imaging. Chemphyschem 4:620-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janes, P. W., S. C. Ley, and A. I. Magee. 1999. Aggregation of lipid rafts accompanies signaling via the T cell antigen receptor. J. Cell Biol. 147:447-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemble, G. W., T. Danieli, and J. M. White. 1994. Lipid-anchored influenza hemagglutinin promotes hemifusion, not complete fusion. Cell 76:383-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenworthy, A. K., B. J. Nichols, C. L. Remmert, G. M. Hendrix, M. Kumar, J. Zimmerberg, and J. Lippincott-Schwartz. 2004. Dynamics of putative raft-associated proteins at the cell surface. J. Cell Biol. 165:735-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kfir, S., M. Ehrlich, A. Goldshmid, X. Liu, Y. Kloog, and Y. I. Henis. 2005. Pathway-and expression level-dependent effects of oncogenic N-Ras: p27Kip1 mislocalization by the Ral-GEF pathway and Erk-mediated interference with Smad signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:8239-8250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppel, D. E., D. Axelrod, J. Schlessinger, E. L. Elson, and W. W. Webb. 1976. Dynamics of fluorescence marker concentration as a probe of mobility. Biophys. J. 16:1315-1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusumi, A., I. Koyama-Honda, and K. Suzuki. 2004. Molecular dynamics and interactions for creation of stimulation-induced stabilized rafts from small unstable steady-state rafts. Traffic 5:213-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson, D. R., J. A. Gosse, D. A. Holowka, B. A. Baird, and W. W. Webb. 2005. Temporally resolved interactions between antigen-stimulated IgE receptors and Lyn kinase on living cells. J. Cell Biol. 171:527-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazarovits, J., H. Y. Naim, A. C. Rodriguez, R. H. Wang, E. Fire, C. Bird, Y. I. Henis, and M. G. Roth. 1996. Endocytosis of chimeric influenza virus hemagglutinin proteins that lack a cytoplasmic recognition feature for coated pits. J. Cell Biol. 134:339-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, K. H., A. D. Holdorf, M. L. Dustin, A. C. Chan, P. M. Allen, and A. S. Shaw. 2002. T cell receptor signaling precedes immunological synapse formation. Science 295:1539-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, S., H. Y. Naim, A. C. Rodriguez, and M. G. Roth. 1998. Mutations in the middle of the transmembrane domain reverse the polarity of transport of the influenza virus hemagglutinin in MDCK epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 142:51-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lommerse, P. H., B. E. Snaar-Jagalska, H. P. Spaink, and T. Schmidt. 2005. Single-molecule diffusion measurements of H-Ras at the plasma membrane of live cells reveal microdomain localization upon activation. J. Cell Sci. 118:1799-1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matallanas, D., V. Sanz-Moreno, I. Arozarena, F. Calvo, L. Agudo-Ibanez, E. Santos, M. T. Berciano, and P. Crespo. 2006. Distinct utilization of effectors and biological outcomes resulting from site-specific Ras activation: Ras functions in lipid rafts and Golgi complex are dispensable for proliferation and transformation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:100-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munro, S. 2003. Lipid rafts: elusive or illusive? Cell 115:377-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakoshi, H., R. Iino, T. Kobayashi, T. Fujiwara, C. Ohshima, A. Yoshimura, and A. Kusumi. 2004. Single-molecule imaging analysis of Ras activation in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:7317-7322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niv, H., O. Gutman, Y. Kloog, and Y. I. Henis. 2002. Activated K-Ras and H-Ras display different interactions with saturable nonraft sites at the surface of live cells. J. Cell Biol. 157:865-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petersen, N. O., S. Felder, and E. L. Elson. 1986. Measurement of lateral diffusion by fluorescence photobleaching recovery, p. 24.21-24.23. In D. M. Weir, L. A. Herzenberg, C. C. Blackwell, and L. A. Herzenberg (ed.), Handbook of experimental immunology. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

- 37.Pizzo, P., E. Giurisato, A. Bigsten, M. Tassi, R. Tavano, A. Shaw, and A. Viola. 2004. Physiological T cell activation starts and propagates in lipid rafts. Immunol. Lett. 91:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prior, I. A., and J. F. Hancock. 2001. Compartmentalization of Ras proteins. J. Cell Sci. 114:1603-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prior, I. A., A. Harding, J. Yan, J. Sluimer, R. G. Parton, and J. F. Hancock. 2001. GTP-dependent segregation of H-ras from lipid rafts is required for biological activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:368-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prior, I. A., C. Muncke, R. G. Parton, and J. F. Hancock. 2003. Direct visualization of Ras proteins in spatially distinct cell surface microdomains. J. Cell Biol. 160:165-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rotblat, B., I. A. Prior, C. Muncke, R. G. Parton, Y. Kloog, Y. I. Henis, and J. F. Hancock. 2004. Three separable domains regulate GTP-dependent association of H-ras with the plasma membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:6799-6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roy, P., Z. Rajfur, P. Pomorski, and K. Jacobson. 2002. Microscope-based techniques to study cell adhesion and migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:E91-E96. [Online.] doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheiffele, P., M. G. Roth, and K. Simons. 1997. Interaction of influenza virus haemagglutinin with sphingolipid-cholesterol membrane domains via its transmembrane domain. EMBO J. 16:5501-5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma, P., R. Varma, R. C. Sarasij, I. K. Gousset, G. Krishnamoorthy, M. Rao, and S. Mayor. 2004. Nanoscale organization of multiple GPI-anchored proteins in living cell membranes. Cell 116:577-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheets, E. D., D. Holowka, and B. Baird. 1999. Critical role for cholesterol in Lyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of FcɛRI and their association with detergent-resistant membranes. J. Cell Biol. 145:877-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shields, J. M., K. Pruitt, A. McFall, A. Shaub, and C. J. Der. 2000. Understanding Ras: “it ain't over ′til it's over.” Trends Cell Biol. 10:147-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shvartsman, D. E., O. Gutman, A. Tietz, and Y. I. Henis. 2006. Cyclodextrins but not compactin inhibit the lateral diffusion of membrane proteins independent of cholesterol. Traffic 7:917-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shvartsman, D. E., M. Kotler, R. D. Tall, M. G. Roth, and Y. I. Henis. 2003. Differently anchored influenza hemagglutinin mutants display distinct interaction dynamics with mutual rafts. J. Cell Biol. 163:879-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simons, K., and D. Toomre. 2000. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1:31-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smart, E. J., G. A. Graf, M. A. McNiven, W. C. Sessa, J. A. Engelman, P. E. Scherer, T. Okamoto, and M. P. Lisanti. 1999. Caveolins, liquid-ordered domains, and signal transduction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:7289-7304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sohn, H. W., P. Tolar, T. Jin, and S. K. Pierce. 2006. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer in living cells reveals dynamic membrane changes in the initiation of B cell signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:8143-8148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tall, R. D., M. A. Alonso, and M. G. Roth. 2003. Features of influenza HA required for apical sorting differ from those required for association with DRMs or MAL. Traffic 4:838-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taner, S. B., B. Onfelt, N. J. Pirinen, F. E. McCann, A. I. Magee, and D. M. Davis. 2004. Control of immune responses by trafficking cell surface proteins, vesicles and lipid rafts to and from the immunological synapse. Traffic 5:651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang, T. Y., R. Leventis, and J. R. Silvius. 2005. Artificially lipid-anchored proteins can elicit clustering-induced intracellular signaling events in Jurkat T-lymphocytes independent of lipid raft association. J. Biol. Chem. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Zacharias, D. A., J. D. Violin, A. C. Newton, and R. Y. Tsien. 2002. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science 296:913-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]