Abstract

Antigen recognition triggers the recruitment of the critical adaptor protein SLP-76 to small macromolecular clusters nucleated by the T-cell receptor (TCR). These structures develop rapidly, in parallel with TCR-induced increases in tyrosine phosphorylation and cytosolic calcium, and are likely to contribute to TCR-proximal signaling. Previously, we demonstrated that these SLP-76-containing clusters segregate from the TCR and move towards the center of the contact interface. Neither the function of these clusters nor the structural requirements governing their persistence have been examined extensively. Here we demonstrate that defects in cluster assembly and persistence are associated with defects in T-cell activation in the absence of Lck, ZAP-70, or LAT. Clusters persist normally in the absence of phospholipase C-γ1, indicating that in the absence of a critical effector, these structures are insufficient to drive T-cell activation. Furthermore, we show that the critical adaptors LAT and Gads localize with SLP-76 in persistent clusters. Mutational analyses of LAT, Gads, and SLP-76 indicated that multiple domains within each of these proteins contribute to cluster persistence. These data indicate that multivalent cooperative interactions stabilize these persistent signaling clusters, which may correspond to the functional complexes predicted by kinetic proofreading models of T-cell activation.

Adaptive immune responses depend on the ability of the T-cell receptor (TCR) to distinguish foreign antigens from self-antigens. These peptide antigens are displayed by major histocompatibility complexes (MHC) on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Peptide-MHC complexes (pMHC) that engage the TCR trigger the sequential recruitment of kinases, scaffolds, and effectors to signaling complexes (5, 46). However, effective T-cell activation is linked to the half-life of the TCR-pMHC interaction. Kinetic proofreading models posit that this correlation results from temporal constraints governing the assembly of the signaling complexes that elicit T-cell activation (19, 34). The precise composition and stoichiometry of these signaling complexes are not well understood and remain topics of intense interest.

Antigen-dependent signals are initiated at the interface between a T cell and an antigen-bearing APC. Frequently, the resulting immunological synapse is reorganized to generate a highly ordered structure characterized by the accumulation of the TCR, costimulatory proteins, and critical signaling molecules in a central domain bounded by adhesion molecules. This domain is referred to as a central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC), whereas the surrounding integrin-rich domain is referred to as a peripheral SMAC (pSMAC). Although the formation of a well-defined cSMAC often predicts effective T-cell activation, the cSMAC does not appear to correspond to the signaling complexes predicted by the kinetic proofreading model (19, 23, 53). First, the cSMAC gradually forms over 15 to 30 min in naive cells (29). Therefore, kinetic arguments preclude a role for the cSMAC in the discrimination of ligands with half-lives differing by seconds. Second, the cSMAC arises too late to drive the rapid changes in tyrosine phosphorylation, intracellular calcium, and cytoskeletal morphology that accompany synapse formation (18, 29, 39). Third, the mature cSMAC is not observed in several types of T cells or in response to certain stimuli (1, 20, 25, 40-42, 44). Finally, the cSMAC can contribute to the down-modulation of TCR-dependent signals (28, 30, 35). These observations indicate that decisive signaling events are independent of the cSMAC.

Modern imaging techniques have begun to reveal macromolecular signaling complexes induced by TCR ligation. These antigen-induced structures bridge the gap between the protein-protein interactions probed by classical biochemical analyses and higher-order structures, such as the cSMAC. TCR-rich microclusters 200 to 500 nm in diameter assemble within seconds of T-cell-APC contact (10, 12, 21, 26, 59). Our own dynamic imaging studies employing immobilized stimulatory antibodies have shown that these microclusters are the predominant sites of TCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and rapidly induce the coaccumulation of tyrosine kinases and critical adaptor proteins, such as SLP-76 (2, 6, 10). We refer to these macromolecular assemblies of signaling molecules as signaling clusters to distinguish them from the signaling complexes probed by traditional biochemical methods. Similar antigen receptor-based signaling clusters arise in T-cell lines, primary human T cells, and mast cells (2, 10, 50, 54, 55, 59). T cells responding to antigen-presenting lipid bilayers or to peptide-bearing APCs develop similar signaling clusters, confirming the relevance of these structures in vivo (12, 59). Critically, a single TCR microcluster is sufficient to induce intracellular calcium elevations, suggesting that individual signaling clusters are competent to initiate critical T-cell activation pathways (10).

The relationship between signaling clusters and the cSMAC is not well understood. In pMHC-induced synapses, TCR microclusters gradually coalesce to form a cSMAC (19, 27, 61). In contrast, signaling clusters containing the critical adaptor SLP-76 are observed in freshly initiated synapses but disappear at later times and fail to colocalize with the cSMAC (59). In the lipid bilayer model, TCR microclusters form in the periphery and move towards the center of the stimulatory interface. Microclusters containing the critical adaptor SLP-76 initially colocalize with the TCR and move towards the center of the contact with similar kinetics. However, the TCR accumulates in a central cluster that is largely devoid of phosphotyrosine, whereas SLP-76 disappears from these structures prior to its centralization (59). In our model system, TCR microclusters remain immobilized by the stimulating antibody but give rise to SLP-76-containing signaling clusters that segregate from the TCR and move towards the center of the stimulatory interface (10). These data indicate that the fates of TCR microclusters and SLP-76-containing signaling clusters diverge during T-cell activation.

Although the adaptor proteins LAT, Grb2, Gads, and SLP-76 cocluster with the TCR early in T-cell activation, relatively little is known about the formation and composition of SLP-76-containing signaling clusters (10, 15, 21). Lipid rafts may play a role in the initiation of signaling; nevertheless, protein-protein interactions appear to play the dominant role in the stabilization of these structures. Given the complexity of the potential interactions among the expected components of these clusters, complexes with diverse stoichiometries are theoretically possible. However, cooperative interactions among the components of these clusters may contribute to the avidities of specific complexes, ensuring that certain protein-protein interactions are favored in vivo and in vitro (6, 13, 22, 31, 62). In this manner, cooperative protein-protein interactions may contribute to the formation of persistent and functionally competent signaling clusters similar to those postulated by kinetic proofreading models.

In our current studies we demonstrate that persistent SLP-76-containing clusters move laterally within the immunological synapses induced by staphylococcal enterotoxin E (SEE), and we examine the properties of analogous SLP-76-containing structures in cells stimulated by immobilized antibodies. In particular, we (i) establish the genetic requirements for the assembly of persistent and mobile SLP-76-containing clusters, (ii) more fully characterize the compositions of these structures, and (iii) demonstrate that multivalent protein-protein interactions play unexpected and critical roles in the assembly and persistence of these structures. Finally, our observations indicate that the persistence of the SLP-76-containing signaling clusters is a decisive factor regulating T-cell activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

All SLP-76 expression constructs used in this study have been described previously (10, 49). All murine cyan fluorescent protein (mCFP)-Gads chimeras were derived by subcloning mutant fragments from murine Gads constructs provided by Jane McGlade (Hospital for Sick Children) into existing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-Gads chimeras and replacing YFP with monomeric CFP bearing an A206K mutation that disrupts the weak dimer interface found in all green fluorescent protein (GFP)-derived proteins (10, 32, 60). The dominant-negative Gads construct was generated by cutting the parental mCFP.Gads construct with ScaI and XmnI, trimming the 3′ overhang with T4 polymerase, and ligating the construct to delete the entire amino terminus of Gads. The LAT-CFP and LAT-DsRed chimeras were generated by subcloning the EcoRI/BamHI fragment encoding human LAT from the LAT-enhanced GFP (EGFP) chimera (described previously) into the pECFP-N1 and pDsRed-N1 expression vectors from Clontech (10). All constructs were validated by sequencing.

Cell lines, transfections, and cell culture.

Parental E6.1 Jurkat T cells and Lck-deficient J.CaM1.6 Jurkat T cells were obtained from ATCC; LAT-deficient J.CaM2.5 Jurkat T cells and SLP-76-deficient J14 Jurkat T cells were gifts from Arthur Weiss (UCSF); and ZAP-70-deficient P116 Jurkat T cells and phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1)-deficient Jγ1 Jurkat T cells were gifts from Robert Abraham (Burnham Institute). Reconstituted variants of these cell lines were obtained from Arthur Weiss, Robert Abraham, and David Strauss (Medical College of Virginia) (52). Nalm-6 B cells were kindly provided by Ann Marie Pendergast (Duke University). J14 cell lines stably expressing wild-type and mutant EGFP.SLP-76 chimeras were either described previously or derived by identical means (49). The J14-derived line stably overexpressing SLP-76.YFP was also described previously (10). All cells were maintained as described previously (49). Cells used for transient transfections were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, glutamine (20 mM), and ciprofloxacin (10 μg/ml). Immediately prior to transfection, cells were rinsed briefly in serum-free medium and resuspended at 4 × 107 cells/ml in complete ciprofloxacin-containing medium. Aliquots of cells (300 μl) were briefly preincubated with no more than 30 μg of experimental and vector DNAs and were transfected in 4-mm-gap cuvettes, using a BTX ECM 830 electroporator set to deliver a single 300-V, 10-ms pulse. After 10 min at room temperature, cells were transferred to prewarmed ciprofloxacin-containing complete medium and allowed to recover for 12 to 16 h prior to analysis.

Antibodies and Western blotting.

Three equivalent antibodies against the human CD3ɛ chain were used interchangeably to trigger T-cell activation and complex formation. Purified OKT3 was obtained from Bio-Express Cell Culture Services (West Lebanon, NH), and purified HIT-3a and UCHT1 were obtained from BD Pharmingen. Each antibody performed similarly in our complex formation assays. Western blotting was performed as described previously to confirm the presence or absence of protein expression in the mutant cell lines (48) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The following antibodies were used: anti-Lck (sc-433) and secondary detection reagents from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., anti-SLP-76 (AS55-P) from Antibody Solutions, Inc., anti-LAT (06-807) and anti-PLC-γ1 (05-163) from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., and anti-ZAP-70 (610240) from BD Transduction Laboratories, Inc.

Cellular imaging and image analysis.

As described previously, complex formation was monitored in Jurkat T-cell lines by using a modified T-cell spreading assay (8). Live images were collected as vertical Z stacks and then subsampled over the plane of the coverslip. Alternately, single z sections were captured over time to improve the rate of image acquisition; in these cases, proper focus was maintained using guide cells with distinguishable fluorescence properties to mark the plane of the coverslip. In studies employing transiently transfected cells, expression levels are heterogeneous. To restrict our analyses to cells expressing physiological levels of protein, we imaged them under fixed conditions, varying only the exposure time. Cells expressing moderate levels of the SLP-76.YFP chimera were identified by comparing the optimal exposure times required to image the experimental cells and control cells stably expressing known levels of the SLP-76 chimera. Only these cells were employed in subsequent analyses. All images were collected using a Perkin-Elmer Ultraview spinning-wheel confocal system mounted on an Axiovert 200 microscope. EGFP and DsRed were detected sequentially using 488-nm and 568-nm laser lines in conjunction with a Perkin-Elmer RGBA dichroic filter and the supplied fluorophore-matched emission filters. CFP and YFP were detected similarly, using 442-nm and 514-nm laser lines in conjunction with a Perkin-Elmer CFP/YFP dichroic filter. Samples were maintained at 37°C. All subsequent image manipulation and analysis were performed using IPLab (Scanalytics).

Functional assays.

For CD69 upregulation experiments, 5 × 105 cells/ml were plated in wells containing medium alone, wells containing medium with 20 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), or wells previously coated with C305 antibody, as described previously (49). After overnight culture, cells were stained with APC-conjugated anti-CD69 (BD Pharmingen), and surface expression was analyzed on a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences). NF-AT assays were set up in glass-bottomed 96-well plates (Whatman) coated with poly-l-lysine, incubated overnight at 4°C with the indicated dilutions of OKT3 in phosphate-buffered saline, and blocked for 1 h at 37°C with 1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (8). Cells to be assayed for NF-AT activation were transfected with 15 μg of a composite NF-AT/AP-1 luciferase reporter plasmid and 3 μg/ml of a control Renilla luciferase expression vector, pRL-TK (16). After recovering overnight, transfected cells were plated at 105 cells/well in a total volume of 100 μl. Positive controls were treated with 50 ng/ml PMA and 1 μM ionomycin. After 6 h at 37°C, plates were assayed for luciferase activity by adding 100 μl of SteadyLite reagent (Perkin-Elmer) directly to the wells of the plate. Renilla luciferase activity was assayed in the same wells by adding 25 μl RenLite reagent to each well, as described previously (45). For both assays, plates were read on a Trilux counter (Perkin-Elmer) approximately 15 min after the addition of the relevant reagent. Controls confirmed that there is no cross-reactivity between AP-1 and Renilla luciferase activities assayed in this fashion. All values were normalized to internal Renilla controls and then to the maximal responses observed in the presence of PMA and ionomycin.

RESULTS

Lateral movement of persistent SLP-76-containing clusters in SEE-induced synapses.

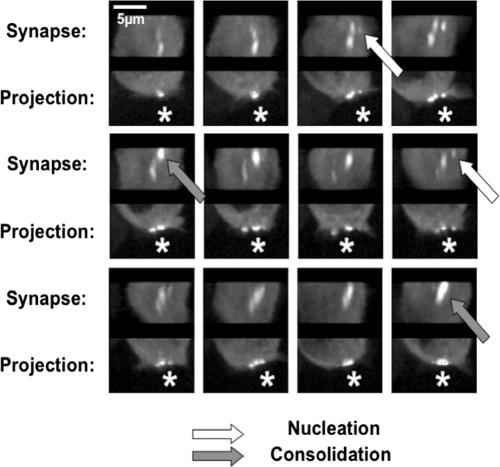

SLP-76-containing signaling clusters have been observed in response to immobilized antibodies and stimulatory lipid bilayers and within the synapses formed by T cells and APCs (10, 12, 59). To examine the dynamics of cluster movement within synapses, we generated conjugates by using SLP-76-deficient Jurkat T cells (J14 cells) stably reconstituted with YFP-tagged SLP-76 (SLP-76.YFP), Nalm-6 B cells, and the bacterial superantigen SEE. To track the lateral movement of SLP-76-containing clusters, we continuously collected three-dimensional image stacks spanning the synapse. In Fig. 1, reconstructed views of the synapse surface (x-z face) reveal that SLP-76-containing clusters formed at the periphery of the synapse, moved laterally within the plane of the synapse, and eventually merged with a larger central cluster of SLP-76 (see Video S1 in the supplemental material). This central cluster faded periodically and appeared to be refreshed by newly arriving clusters. Thus, the lateral movement of persistent SLP-76-containing clusters within the plane of the synapse is a common feature observed with all three imaging systems discussed above (10, 12, 59).

FIG. 1.

SLP-76-containing complexes in SEE-induced synapses. J14 Jurkat T cells stably expressing SLP-76.YFP were allowed to form synapses in the presence of Nalm-6 B cells and 5 μg/ml SEE. Conjugates were detected 10 to 20 min after the initiation of the assay. SLP-76-containing complexes were observed in the synapses of all conjugates. SLP-76 was imaged within synapses by continuously collecting three-dimensional image sets spanning the synapse. Images were collected with a vertical spacing of 0.3 μm, and full image sets were collected every 16 seconds. The images shown here were collected at 32-second intervals. At each time point, two views of the synapse were created, including a maximum projection of the entire image set, revealing all of the clusters in the synapse in a single image, and a reconstructed head-on view of the synapse. Asterisks mark the position of the Nalm-6 B cell, and arrows identify sites of SLP-76 nucleation (white) and consolidation (gray).

Upstream requirements for cluster formation, persistence, and translocation.

We postulated that the persistent and mobile SLP-76-containing signaling clusters observed with the three imaging systems correspond to the minimal effective complexes predicted by kinetic proofreading models of T-cell activation. To test the correspondence between cluster formation and T-cell activation, we employed antibody-coated glass surfaces as described previously. Given that persistent and laterally mobile SLP-76-containing clusters formed in each model system, the two planar imaging systems offered several advantages. Both systems immobilize the stimulated cells, allow the prediction of the plane of stimulation, and permit the capture of the entire contact surface in a single image. In particular, our plate-bound assay immobilizes engaged TCRs and therefore enables the visualization of SLP-76 apart from the initiating receptor. In addition, our spinning-disc confocal assay is more amenable to dynamic multicolor studies than are standard total internal reflection/fluorescence-based systems.

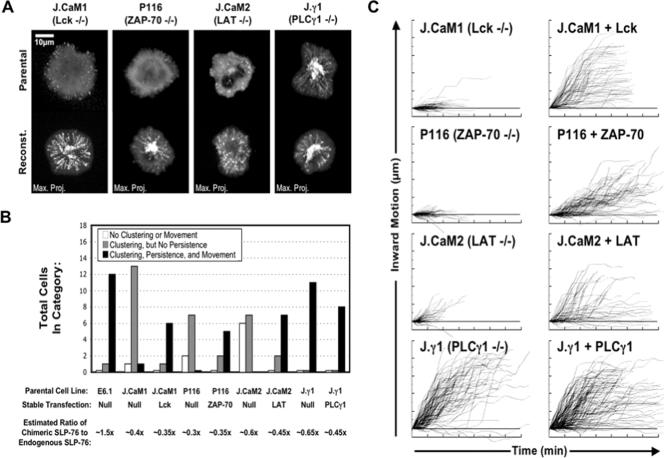

Lck, ZAP-70, LAT, and PLC-γ1 have been predicted to play roles in cluster assembly or stabilization, and they play critical roles in T-cell activation. To test whether cluster formation, persistence, or movement correlated with normal activation, we examined Jurkat-derived T-cell lines lacking these proteins (J.CaM1, P116, J.CaM2, and Jγ1, respectively) (31). The loss and reconstitution of these signaling proteins are confirmed in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. To quantitate differences in cluster formation, persistence, and movement in these cell lines, we identified moving complexes in maximum-over-time projections, traced individual cluster trajectories in kymographs, and presented the average behavior of these clusters, using composite kymographs and mean translocation plots (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). To limit our analyses to cells expressing approximately physiological levels of protein, we identified and analyzed only those cells that expressed moderate levels of SLP-76.YFP, as determined by comparison with a control cell line stably overexpressing known amounts of SLP-76 (see Materials and Methods). Representative maximum-over-time projections (Fig. 2A) reveal that all aspects of cluster formation are compromised in the absence of Lck, ZAP-70, or LAT. Overall, fewer cells formed clusters, and those clusters that did form neither persisted nor translocated (Fig. 2B). These defects are specific to the deficiencies in question, as reconstitution restored normal cluster behavior in these cell lines. Thus, cluster persistence and movement are correlated with effective T-cell activation.

FIG.2.

Genetic requirements for complex assembly. Jurkat variants and their stably reconstituted partners were transiently transfected with SLP-76.YFP. (A) Maximum-over-time projections are shown for representative mutant (top row) and reconstituted (bottom row) cells. (B) Summary of the observed microcluster phenotypes in transiently transfected cells. For each condition, at least three independent transfections were performed, and three to five imaging runs were performed per transfection. All cells meeting the expression criteria described in Materials and Methods were sorted into the following three categories: cells displaying no clustering, cells displaying transient clusters that failed to move, and cells displaying persistent, mobile clusters. Overexpression of the SLP-76 chimera was estimated on a per-cell basis by comparing the experimental exposure time to the time required to image a cell expressing a known amount of an identical chimera (not shown). (C) Movement traces of the most persistent and mobile complexes observed in each cell were extracted and compiled into composite kymographs. This approach understates the defects observed in nonreconstituted cell lines. (D) Mean translocation plots were compiled from the individual movement traces shown in panel C. The numbers of traces compiled are indicated. (E) Jurkat T cells stably expressing either SLP-76.YFP or ZAP-70.YFP were assayed for complex formation after a 30-min pretreatment with 10 μM PP2 or with carrier alone (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). Maximum-over-time projections are shown for representative SLP-76.YFP-expressing cells (top row), whereas still frames are shown for the ZAP-70.YFP-expressing cells (bottom row).

The quantitation of cluster persistence and movement revealed that clusters that formed in the parental Jurkat line persisted for 5 to 6 min, moved 4 to 5 μm from their sites of origin, and initially traveled at speeds of 2 μm/minute, with individual clusters achieving speeds as high as 4 μm/minute (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). On average, the few clusters that formed in the mutant cell lines persisted for no more than 2 min, moved no more than 1 μm, and moved no faster than 0.5 μm/minute (Fig. 2C and D). In contrast, the SLP-76-containing clusters observed in the Lck-, ZAP-70-, and LAT-reconstituted cell lines were grossly normal. These clusters persisted for 4 to 6 min and traveled 2 to 4 μm at average speeds between 0.5 and 1.5 μm/minute. Individual clusters achieved speeds of 2 to 4 μm/minute. These data further indicate that normal cluster persistence and movement are associated with effective T-cell activation.

Since abortive cluster formation was observed in the Lck-, ZAP-70-, and LAT-deficient cell lines, we hypothesized that a distinct Fyn-dependent pathway might account for residual cluster-nucleating activity. PP2, a drug that inhibits both Lck and Fyn, blocked the formation of SLP-76-containing complexes at doses that prevented the recruitment of ZAP-70 to the TCR (Fig. 2E). This is consistent with a role for Fyn in the formation of the labile SLP-76-containing clusters observed in the absence of Lck, ZAP-70, or LAT.

Although PLC-γ1 interacts with multiple components of LAT-nucleated signaling complexes and may participate in cooperative interactions within the complex, SLP-76-containing clusters behaved normally in the PLC-γ1-deficient Jγ1 cell line (Fig. 2A to D) (6, 31). Since these cells are incapable of normal activation, these data indicate that complex formation is insufficient for maximal activation in the absence of an essential downstream effector. Although this formally indicates that PLC-γ1 does not play a significant role in cluster stabilization in this model system, the Jγ1 cell line expresses the highly related protein PLC-γ2. This PLC isoform is phosphorylated in response to TCR ligation and may compensate to some degree for the absence of PLC-γ1 (24).

Multiple domains of SLP-76 contribute to cluster formation, persistence, and translocation.

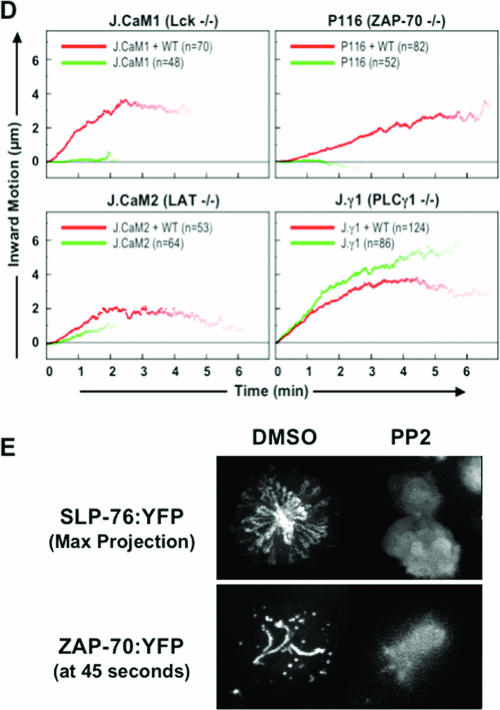

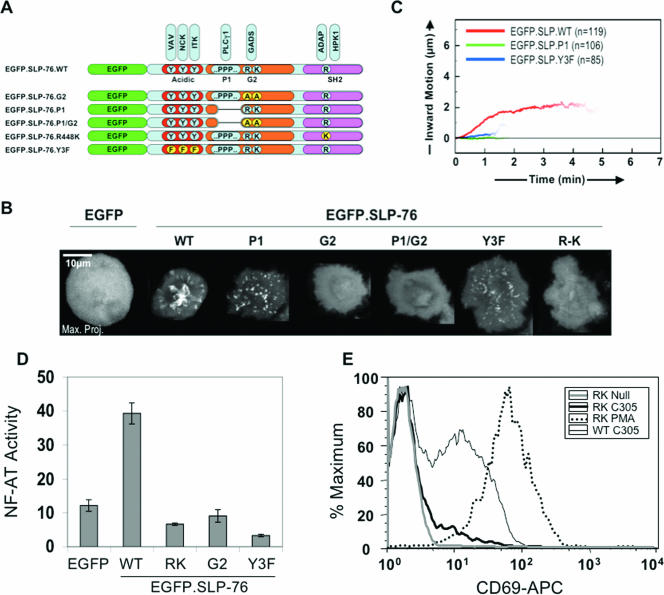

To identify the molecular mechanisms regulating the formation, persistence, and translocation of SLP-76-containing clusters, we monitored the behavior of these clusters in SLP-76-deficient Jurkat cells stably reconstituted with EGFP-tagged variants of SLP-76 (Fig. 3A). The primary role in the recruitment of SLP-76 to LAT has been attributed to the Gads-binding motif of SLP-76. Additional protein-protein interaction domains include (i) a triply tyrosine-phosphorylated domain that interacts with the SH2 domains of Vav, Nck, and Itk; (ii) the P1 domain, a 67-amino-acid proline-rich region initially identified as a PLC-γ1-binding site; and (iii) the SH2 domain, which binds the adaptor ADAP and the serine/threonine kinase HPK1 (7, 9, 14, 32, 36, 43, 47, 49, 58). To minimize the risk of clonal artifacts, our stable lines were derived as polyclonal populations by high-speed cell sorting and matched for EGFP.SLP-76 expression by flow cytometry and Western blotting (49). These amino-terminally tagged SLP-76 chimeras (EGFP.SLP-76) translocate to the center of the contact surface (Fig. 3B) (49), as originally shown for SLP-76 chimeras tagged at the carboxy terminus (SLP-76.YFP) (10). These clusters traveled approximately 2 μm inward, persisted for approximately 4 min, and achieved speeds of approximately 1 μm/minute (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the assembly, persistence, and movement of clusters were severely defective in all mutant lines (Fig. 3B and C; see Video S2 in the supplemental material). In particular, the P1-deleted (P1) and tyrosine mutant (Y3F) chimeras assembled into clusters that dissipated within 90 seconds, without undergoing significant medial movement, whereas the Gads-binding mutant (G2) and SH2 domain mutant (RK) chimeras were not recruited into clusters at all. Although the tyrosine-phosphorylated domain, the P1 domain, and the SH2 domain are commonly viewed as effector docking sites, our results indicate that these domains play unexpectedly important roles in the assembly, persistence, and movement of SLP-76-containing clusters. We predict that each of the domains tested here contributes molecular interactions that cooperate to stabilize SLP-76-containing clusters.

FIG. 3.

SLP-76 domains contribute to complex assembly and T-cell activation. (A) Schematic of EGFP.SLP-76 and mutant variants. (B) Complex formation and movement in J14 cells stably reconstituted with EGFP, wild-type EGFP.SLP-76, or EGFP.SLP-76 are displayed using representative maximum-over-time projections. Images were acquired from multiple runs performed over three or more independent experiments. (C) Translocation plots display the mean persistence and translocation of complexes observed as described for panel B. For each plot, traces were acquired from 4 to 10 representative cells identified from multiple imaging runs performed in two or more independent experiments. The numbers of traces compiled are indicated. (D) NF-AT-luciferase activation assays were performed in SLP-76-deficient cell lines stably transfected with the indicated EGFP.SLP-76 chimeras or in control cells expressing EGFP alone. Stimulation was performed on immobilized antibodies in glass-bottomed 96-well plates. The standard deviations of triplicate samples are shown. Similar results were obtained in three experiments. (E) SLP-76-deficient Jurkat T cells stably reconstituted with wild-type SLP-76 (WT) or with SH2 domain mutant SLP-76 (RK) were stimulated and stained for CD69.

Cluster formation, persistence, and translocation are associated with effective T-cell activation.

Previous studies have shown that all of the SLP-76 domains tested above contribute to T-cell activation (17, 37, 49, 58). However, some experiments suggest a limited role for the SLP-76 SH2 domain in T-cell activation (4). To determine whether differences in the mode of stimulation account for these apparent differences in the function of the SH2 domain, we subjected several of the SLP-76-expressing cell lines to NF-AT/AP-1 reporter assays in glass-bottomed 96-well plates, under stimulation conditions identical to those used in our imaging experiments. We consistently observed severe defects in NF-AT/AP-1 induction in the SH2 domain mutant (Fig. 3D). In addition, CD69 upregulation was substantially impaired in this mutant (Fig. 3E). In conjunction with our previous studies, these data indicate that every SLP-76 mutation that results in altered cluster formation or persistence impairs T-cell activation, as summarized in Table 1 (38, 49). Thus, the cooperative stabilization of SLP-76-containing clusters appears to be required for effective T-cell activation.

TABLE 1.

Correlations between complex formation and T-cell activationa

| Mutation | Presence of characteristic in mutant

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J14 cell line expressing EGFP.SLP-76 chimera

|

SLP-76 knockout plus transgene

|

|||||||

| Complex characteristic

|

Ca2+b | CD69c upregulation | NF-AT activationd | Thymic development§e | T-cell proliferation§f | |||

| Formation* | Persistence* | Movement* | ||||||

| Null | − | − | − | −† | −† | −*† | DN3 block (0.3) | − |

| Y3F | + | − | − | −§ | −§ | −* | DN3 block (1.0) | − |

| P1 | + | − | − | +† | +† | +† | ND | ND |

| G2 | − | − | − | +† | +† | −*† | DN3 block (20.0) | ++ |

| P1/G2 | − | − | − | −† | −† | −† | ND | ND |

| SH2 | − | − | − | +++§ | +* | −* | DN3 block (70) | ++ |

| WT | + | + | + | +++†§ | +++*† | +++*† | No block (100) | +++ |

Items marked with “*” are based on observations described here, items marked with “†” are derived from our previous study (49), and items marked with “§” are derived from the transgenic studies of Myung et al. (38). The effects of the SH2 domain mutation on TCR-induced CD69 upregulation are included in Fig. 3E. The effects of the Y3F mutation on CD69 upregulation and the effects of the Y3F and SH2 domain mutations on TCR-induced calcium fluxes were obtained from the work of Myung et al. Data pertaining to the Δ224-244 Gads-binding site deletion and the G2 point mutations in the Gads-binding site are combined here.

Normal calcium fluxes are reported as “+++.” Calcium fluxes with reduced peak and sustained levels are reported as “+.”

CD69 upregulation in wild-type cells is shown as “+++.” Mutant cell lines displaying a small population of CD69-positive cells are labeled “+.”

NF-AT activation that is above background but less than 25% of that observed in wild-type cells is shown as “+.”

Two observations are reported, including the presence or absence of a developmental block at the DN3 stage and the percentage of normal thymic cellularity achieved upon expression of the indicated SLP-76 transgenes (in parentheses). ND, not done.

Proliferation is scored based on the dose of anti-CD3ɛ required to induce half-maximal thymidine incorporation. Wild-type cells respond to 6 to 20 μg/ml. Cells scored “++” respond to 20 to 60 μg/ml. ND, not done.

SLP-76 and Gads cooperate to facilitate cluster formation.

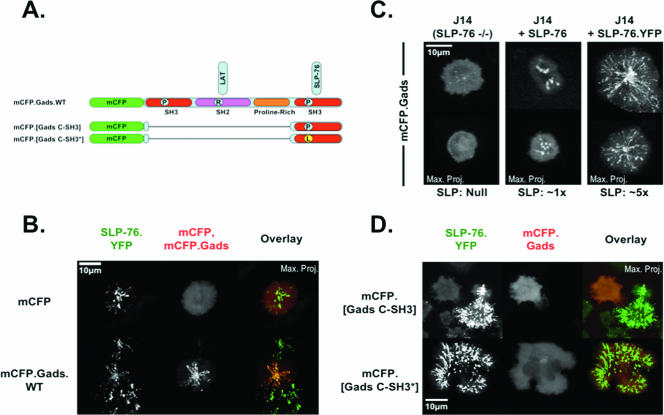

To further address the cooperative interactions regulating cluster formation, we examined the role of Gads in greater detail. Although we initially reported that Gads is only transiently recruited to signaling clusters, the Gads-binding G2 domain of SLP-76 is absolutely required for cluster nucleation (10). To clarify the role of Gads in cluster formation, we coexpressed a monomeric CFP-tagged wild-type Gads chimera (mCFP.Gads) with SLP-76.YFP (Fig. 4A; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Under these conditions, Gads entered persistent clusters in response to TCR ligation, colocalizing precisely with SLP-76 (Fig. 4B; see Video S3 in the supplemental material). Unexpectedly, Gads did not enter clusters in the absence of SLP-76 (Fig. 4C, left panel). The physiological levels of SLP-76 in reconstituted J14 cells enabled the recruitment of Gads into clusters that dissipated rapidly (Fig. 4C, center panel), whereas higher levels of SLP-76 permitted the recruitment of Gads into persistent, mobile clusters (Fig. 4C, right panel).

FIG. 4.

SLP-76 and Gads cooperate to stabilize complexes. (A) Schematic of Gads chimeras tagged with monomeric CFP (mCFP) at the amino terminus. (B) mCFP and the wild-type mCFP.Gads chimera were transiently expressed in J14 cells stably reconstituted with SLP-76.YFP. Complex formation assays were performed, and the resulting maximum-over-time projections are shown for YFP (left panels, green overlay) and mCFP (middle panels, red overlay). (C) mCFP.Gads was transiently transfected into J14 cells, J14 cells stably reconstituted with moderate levels of untagged SLP-76, and J14 cells stably reconstituted with high levels of SLP-76.YFP. The resulting cells were stimulated, and mCFP-Gads was imaged. Two representative maximum-over-time projections are shown for each condition. (D) The mCFP-tagged C-terminal SH3 domain of Gads and an identical construct with an inactivated SH3 domain were transiently transfected into J14 cells stably reconstituted with SLP-76.YFP. Complex formation assays were performed, and maximum-over-time projections are shown for both SLP-76 (left panels, green overlay) and the wild-type and mutant dominant-negative constructs (middle panels, red overlay).

These observations clearly indicate that SLP-76 controls the localization of Gads. However, this observation contradicts existing biochemical data indicating that Gads controls the recruitment of SLP-76 into complexes (32). To confirm that Gads can regulate the localization of SLP-76, we created a dominant-negative version of Gads by fusing the carboxy-terminal SH3 domain of Gads to an amino-terminal mCFP tag (Fig. 4A). This dominant-negative construct blocked the recruitment of SLP-76 into clusters, whereas a control construct with a single SH3 domain-inactivating point mutation had no effect on cluster formation (Fig. 4D; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). As anticipated, this dominant-negative effect was strongly dose dependent (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Jointly, these observations demonstrate that the recruitment of Gads to LAT requires SLP-76 and that the recruitment of SLP-76 to LAT requires Gads. These observations are incompatible with linear models of cluster formation but are easily reconciled in models where Gads and SLP-76 cooperate to influence cluster nucleation and persistence.

Multiple domains of Gads contribute to cluster formation and translocation.

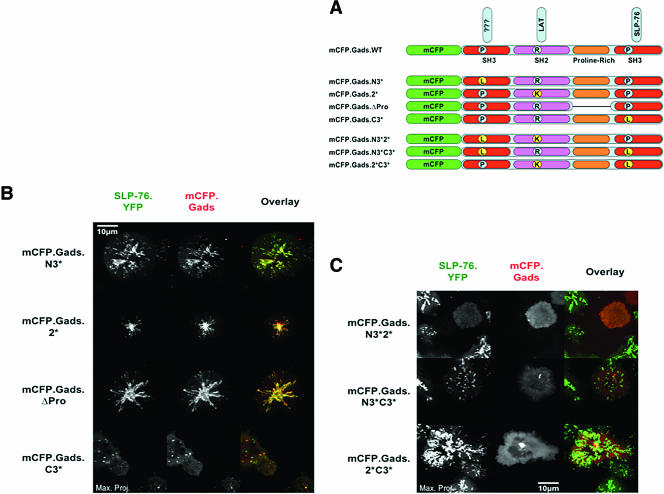

The isolated carboxy-terminal SH3 domain of Gads potently inhibited the recruitment of SLP-76 into clusters, indicating that the absent amino-terminal domains of Gads normally play critical roles in cluster formation. Three protein interaction domains have been identified in this region of Gads, including the amino-terminal SH3 domain, an SH2 domain, and a proline-rich linker (3, 32). To identify the Gads domains contributing to cluster formation, we transfected a panel of mCFP-tagged Gads chimeras into our SLP-76.YFP-expressing J14 cells (Fig. 5A; see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Wild-type Gads colocalized perfectly with SLP-76 in persistent, mobile clusters (Fig. 5B). Mutation in either the amino-terminal SH3 domain (Gads.N3*) or the proline-rich region (Gads.ΔPro) did not affect the recruitment of Gads into clusters, whereas mutation of the carboxy-terminal SH3 domain (Gads.C3*) created a dominant-negative chimera that inhibited the persistence and movement of SLP-76-containing clusters (Fig. 5B). This behavior is analogous to that exhibited by the isolated carboxy-terminal SH3 domain of Gads in Fig. 4D. Unexpectedly, mutation of the SH2 domain, which was expected to play an essential role in cluster formation by linking the Gads chimera with LAT, had no effect on cluster formation or the recruitment of Gads into clusters (Fig. 5B; see Video S4 in the supplemental material). Since considerable biochemical data support the important role of the Gads SH2 domain in T-cell activation, we also examined the behaviors of Gads chimeras containing paired mutations (Fig. 5A). Mutation of both the amino-terminal SH3 domain and the SH2 domain resulted in the generation of a dominant-negative Gads chimera that was not recruited into complexes and inhibited the recruitment of SLP-76 into clusters (Fig. 5C; see Video S5 in the supplemental material). This result confirms that the SH2 domain plays an essential but partially redundant role in cluster formation. The mutation of both SH3 domains created a less potent dominant-negative Gads chimera that was not recruited into clusters but only partially inhibited the recruitment of SLP-76 into clusters (Fig. 5C). In contrast, mutation of the SH2 domain and the carboxy-terminal SH3 domain created an inert Gads chimera that was not recruited into clusters and did not perturb the localization of SLP-76 (Fig. 5C; see Video S6 in the supplemental material). These data reveal an unexpected complexity of Gads interactions. There are at least two functional regions within Gads, namely, the carboxy-terminal SH3 domain, which is sufficient to direct the interaction between Gads and SLP-76, and an amino-terminal region comprising the first SH3 domain and the SH2 domain, which each appear to promote the interaction of Gads with LAT.

FIG. 5.

Gads domains contribute to complex assembly. (A) Schematic of mCFP.Gads mutants. (B) mCFP.Gads constructs containing mutations in individual domains were transiently transfected into J14 cells stably reconstituted with SLP-76.YFP. Complex formation assays were performed, and maximum-over-time projections for both SLP-76 (left panels, green overlay) and Gads (middle panels, red overlay) are presented for representative cells. (C) mCFP.Gads constructs containing mutations in multiple domains were analyzed as described for panel B.

Protein-protein interactions govern the recruitment of LAT into signaling clusters.

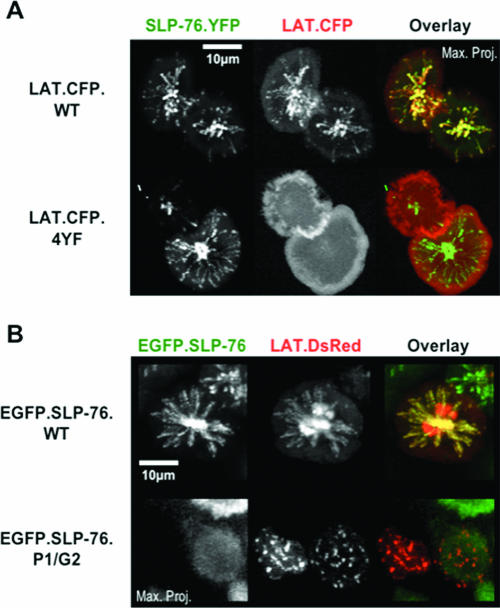

Phosphotyrosine-dependent protein-protein interactions play an important role in the recruitment of LAT into signaling clusters (10, 15, 21). Since our data indicate that the entry of Gads into clusters is influenced by its interaction with SLP-76, we hypothesized that the recruitment of LAT into signaling clusters is regulated by Gads and SLP-76. In the absence of exogenous SLP-76, LAT chimeras entered clusters that dissipated rapidly (10). In this study, we expressed a CFP-tagged wild-type LAT chimera (LAT.CFP.WT) in SLP-76.YFP-reconstituted J14 cells. This LAT chimera was recruited into persistent SLP-76-containing clusters that were transported medially (Fig. 6A, top row; see Video S7 in the supplemental material). Four critical carboxy-terminal tyrosines in LAT have been implicated in binding Gads, Grb2, and PLC-γ1. A mutant LAT chimera lacking these tyrosines (LAT.CFP.4YF) remained uniformly distributed in the plasma membrane following TCR ligation, even though the coexpressed SLP-76 chimera, presumably interacting with endogenous LAT, clustered normally (Fig. 6A, bottom row; see Video S8 in the supplemental material). These data indicate that phosphotyrosine-mediated protein-protein interactions drive the clustering of LAT, as we and others have argued previously (10, 15, 21).

FIG. 6.

Protein-protein scaffolds recruit LAT into signaling complexes. (A) Wild-type (LAT.CFP.WT) and tyrosine mutant (LAT.CFP.4YF) LAT chimeras were transiently transfected into J14 cells stably reconstituted with SLP-76.YFP. Complex formation assays were performed, and maximum-over-time projections for both SLP-76 (left panels, green overlay) and LAT (middle panels, red overlay) are presented for representative cells. (B) LAT.DsRed was transiently transfected into J14 cells stably expressing either a wild-type (EGFP.SLP-76.WT) or mutant (EGFP.SLP-76.P1/G2) SLP-76 chimera. Although the recipient cell lines were matched for SLP-76 expression by flow cytometry, rare cells did not express the SLP-76 chimera (bottom row). Complex formation assays were performed, and maximum-over-time projections for both SLP-76 (left panels, green overlay) and LAT (middle panels, red overlay) are presented for representative cells.

To test whether the impaired association of the LAT-4YF mutant with Gads, SLP-76, and PLC-γ1 is responsible for the failed assembly of LAT into signaling clusters, we tagged wild-type LAT with a red fluorescent protein. We expressed the resulting chimera, LAT.DsRed, in J14 cell lines stably reconstituted with either the wild-type EGFP.SLP-76 chimera or matched levels of the P1/G2 double-mutant chimera, which cannot bind Gads or PLC-γ1. Although the DsRed fluorescent tag induced some nonspecific aggregation of LAT, the LAT.DsRed chimera clearly assembled into clusters with wild-type EGFP.SLP-76 (Fig. 6B, top row). LAT and SLP-76 persisted in these clusters and coordinately moved to a central compartment. Although the LAT.DsRed chimera entered signaling clusters in the P1/G2 mutant line, these clusters were less persistent (not shown) and did not display directed movement (Fig. 6B, bottom row), indicating that the translocation of LAT required its interaction with Gads and SLP-76. Since the LAT chimera behaved in the same manner in the absence of SLP-76 (compare the left and right cells in the bottom row of Fig. 6B), the residual LAT clustering must be independent of SLP-76. These observations indicate that the assembly of LAT into clusters capable of translocation requires SLP-76 but that alternate tyrosine-dependent mechanisms recruit LAT into transient, static clusters.

DISCUSSION

SLP-76-containing signaling clusters participate in T-cell activation.

SLP-76-containing clusters have been reported for T cells stimulated by three distinct mechanisms, i.e., in response to immobilized antibodies, in response to lipid bilayers bearing stimulatory pMHC, and in response to antigen (or superantigen)-presenting B cells (10, 12, 59). In all three systems, micrometer-scale clusters rich in SLP-76 form at sites of TCR ligation at the periphery of the contact surface and persist while moving towards the center of the contact surface. These structures arise in regions of tight contact in the F-actin-rich cell periphery, recruit critical adaptors and effector proteins within seconds of TCR ligation, and suffice to initiate cytoplasmic calcium increases (2, 10-12, 59). In addition, every cell line displaying impaired cluster assembly or persistence fails to respond effectively to TCR ligation. These observations indicate that SLP-76-containing clusters are functional. Furthermore, these structures assemble within the kinetic window dictated by the half-lives of effective TCR-pMHC interactions (10, 19). Thus, these SLP-76-containing clusters may correspond to the essential signaling clusters predicted by the kinetic proofreading model.

Fates of SLP-76-containing signaling clusters.

In all three imaging systems discussed above, SLP-76-containing clusters are seen to persist, move towards the center of the contact interface, and ultimately diverge from their initiating TCR microclusters. In our study, the SLP-76-containing clusters induced by superantigen move laterally within the contact interface and can be detected within this interface for 20 to 30 min. Although lateral cluster movement and central accumulation were not observed in the superantigen-induced contacts studied by Yokosuka et al., their studies examined SLP-76-containing clusters 30 min after contact formation (59). By this time, the clusters observed in our studies had typically dissipated. Antigen-presenting lipid bilayers induce signaling clusters that colocalize with the TCR in mobile clusters until SLP-76 disappears during its transit towards the center of the contact surface (59). The failure to observe centralized SLP-76-containing clusters on lipid bilayers may result from the failure to detect internalized structures, as the illumination employed in total internal reflection/fluorescence-based studies only penetrates to depths of 50 to 100 nm. Alternately, centralized SLP-76-containing structures may not be observed because of differences in the nature of the responding cell (primary cell versus cell line), the quality of the TCR ligand (pMHC versus superantigen), or the costimulatory molecules presented by the stimulatory surface (lipid bilayer versus intact B cell). Finally, immobilized antibodies induce SLP-76-containing clusters that segregate from initiating TCR microclusters and move towards the center of the contact surface (10). Although this last system, which was employed in these studies, is the only system to give rise to SLP-76-containing clusters that demonstrably persist apart from the TCR, this difference may be due to the artificial immobilization of the TCR by stimulatory antibodies. Although further studies will be required to determine how differences in the methods of stimulation and visualization influence cluster formation and persistence, our observations indicate that SLP-76-containing clusters can persist apart from the TCR and that these clusters are capable of temporarily maintaining their integrity in the absence of continuous interactions with TCR microclusters.

Multiple protein-protein interactions regulate cluster nucleation and persistence.

The SLP-76-containing clusters described above are poised to regulate T-cell activation. However, the precise composition of these clusters remains undefined. The studies presented here confirm that the anticipated protein-protein interactions play critical roles within these clusters (i.e., the Gads SH2 domain, the Gads C-SH3 domain, and the Gads-binding G2 site in SLP-76). However, our studies have demonstrated that several protein interaction domains previously thought to function as effector recruitment sites play important roles in the assembly and stabilization of signaling clusters.

Dramatically, the inactivation of the SLP-76 SH2 domain abolishes the recruitment of SLP-76 into clusters, blocks CD69 upregulation, and prevents the activation of NF-AT. Although some studies have indicated a limited role for the SH2 domain, a partially redundant role in cluster nucleation may have been obscured by the constitutive membrane localization of the SLP-76 chimeras used in these studies (4). Additional studies performed with SLP-76-deficient cells stably reconstituted with SH2 domain mutants or Gads-binding-site mutants confirmed that the roles played by these two sites are comparable and essential (38, 58). The critical SH2 domain ligand supporting complex nucleation has not yet been defined. The adaptor ADAP and the serine-threonine kinase HPK1 are likely candidates, as these proteins bind the SLP-76 SH2 domain and are capable of engaging components of the TCR-proximal signaling complex independently of SLP-76 (14, 33, 47). Therefore, multivalent interactions involving SLP-76 and ADAP or HPK1 could stabilize the observed signaling clusters.

The proline-rich P1 domain and the amino-terminal tyrosines of SLP-76 are best known for their effector-binding properties. Nevertheless, both domains are required for persistent cluster formation (38, 49). Given the important role of the P1 domain and the biochemical evidence in favor of a cooperative bridging model in which PLC-γ1 links SLP-76 to LAT, we were surprised to find that PLC-γ1 is not required for the formation, persistence, or movement of SLP-76-containing clusters (31). Thus, the cooperative interactions reported to recruit PLC-γ1 into signaling clusters may not contribute to the overall stability of individual SLP-76-containing clusters. Although PLC-γ2 is present in the Jγ1 line and may compensate for any structural role associated with PLC-γ1, our mutational analyses also indicated that the P1 domain contributes to cluster stability and effective T-cell activation (24). Thus, an as yet uncharacterized ligand of the P1 domain is likely to play an important role in cluster stabilization (58). Similarly, we do not yet understand how the amino-terminal tyrosines of SLP-76 contribute to cluster stability, i.e., whether they work through cooperative protein-protein interactions or through the catalytic functions of associated proteins (9, 56, 57). Regardless of how these domains contribute to complex stability, our observations emphasize the utility of imaging approaches that directly evaluate cluster formation as a complement to traditional biochemical and functional approaches.

Cooperative interactions stabilize SLP-76-containing clusters.

Cooperative models of complex formation have been invoked to explain the requirement that several distinct phosphorylation sites be present on each LAT molecule (31). Our observations are inconsistent with common linear models of complex formation. First, four distinct regions within SLP-76 contribute to cluster formation and persistence, indicating that these regions cooperate to stabilize signaling complexes. Second, SLP-76 controls the recruitment of Gads into clusters. Finally, Gads does not act as a simple bifunctional bridge between LAT and SLP-76. Instead, the amino-terminal SH3 domain and the SH2 domain of Gads are partially redundant with respect to cluster formation and cooperate to recruit Gads into LAT-nucleated clusters. These data support a model in which LAT, Gads, and SLP-76 act as a core signaling cluster stabilized by multiple cooperative interactions among these proteins and additional cluster constituents (6).

Defective signaling clusters are rapidly terminated.

While certain alterations abolish cluster formation altogether, diverse perturbations of the SLP-76-containing clusters result in the dissociation of these structures within 90 to 120 seconds, prior to the initiation of medial cluster movement. This effect has been observed in cells lacking Lck, ZAP-70, or LAT, in cells expressing SLP-76 mutants affected in either the amino-terminal tyrosines or the P1 domain, and in cells expressing dominant-negative variants of Gads. The similarity of these behaviors suggests that the failure to persist is regulated by a conserved inhibitory mechanism triggered in response to partial signaling, as predicted by modified versions of the kinetic proofreading model (51). We speculate that this inhibitory process is dampened in cells that assemble mature SLP-76-containing clusters.

Implications of cooperative cluster formation.

We have demonstrated a strong relationship between the persistence of cooperatively stabilized SLP-76-containing signaling clusters and optimal T-cell activation (Table 1). We predict that this relationship arises because cooperative cluster stabilization serves several critical needs. First, cooperative interactions may support cluster formation and antagonize cluster dissociation by enabling the assembly of high-avidity macromolecular complexes from multiple low-affinity protein-protein interactions. In this manner, cooperative interactions may increase antigen sensitivity and sharpen the thresholds regulating the discrimination of antigen from self. Second, the diverse interactions within a cooperatively assembled cluster may facilitate the integration of multiple costimulatory or suppressive inputs by providing multiple targets for the modulation of T-cell responses. Finally, highly favorable cooperative interactions may constrain the topology of mature signaling clusters, enabling the selective recruitment of adaptors to LAT in vivo (13, 22, 31, 62). A better understanding of these complex intermolecular interactions will enable the modulation of immune responses by endogenous signaling pathways and by targeted pharmacologic agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Arthur Weiss, Robert Abraham, and David Strauss for various Jurkat cell lines, C. Jane McGlade for Gads expression constructs, and Jon Houtman for many helpful discussions.

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (F32-DK09969 to A.L.S. and P01-CA93615 to M.S.J. and G.A.K.). S.C.B. was a fellow of the Cancer Research Institute. D.I.H. was a Howard Hughes Medical Institute-National Institutes of Health research scholar.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balamuth, F., D. Leitenberg, J. Unternaehrer, I. Mellman, and K. Bottomly. 2001. Distinct patterns of membrane microdomain partitioning in Th1 and Th2 cells. Immunity 15:729-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barda-Saad, M., A. Braiman, R. Titerence, S. C. Bunnell, V. A. Barr, and L. E. Samelson. 2005. Dynamic molecular interactions linking the T cell antigen receptor to the actin cytoskeleton. Nat. Immunol. 6:80-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry, D. M., P. Nash, S. K. Liu, T. Pawson, and C. J. McGlade. 2002. A high-affinity Arg-X-X-Lys SH3 binding motif confers specificity for the interaction between Gads and SLP-76 in T cell signaling. Curr. Biol. 12:1336-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boerth, N. J., J. J. Sadler, D. E. Bauer, J. L. Clements, S. M. Gheith, and G. A. Koretzky. 2000. Recruitment of SLP-76 to the membrane and glycolipid-enriched membrane microdomains replaces the requirement for linker for activation of T cells in T cell receptor signaling. J. Exp. Med. 192:1047-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boniface, J. J., J. D. Rabinowitz, C. Wulfing, J. Hampl, Z. Reich, J. D. Altman, R. M. Kantor, C. Beeson, H. M. McConnell, and M. M. Davis. 1998. Initiation of signal transduction through the T cell receptor requires the multivalent engagement of peptide/MHC ligands. Immunity 9:459-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braiman, A., M. Barda-Saad, C. L. Sommers, and L. E. Samelson. 2006. Recruitment and activation of PLCgamma1 in T cells: a new insight into old domains. EMBO J. 25:774-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bubeck Wardenburg, J., R. Pappu, J. Y. Bu, B. Mayer, J. Chernoff, D. Straus, and A. C. Chan. 1998. Regulation of PAK activation and the T cell cytoskeleton by the linker protein SLP-76. Immunity 9:607-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunnell, S. C., V. A. Barr, C. L. Fuller, and L. E. Samelson. 2003. High-resolution multicolor imaging of dynamic signaling complexes in T cells stimulated by planar substrates. Sci. STKE 2003:PL8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunnell, S. C., M. Diehn, M. B. Yaffe, P. R. Findell, L. C. Cantley, and L. J. Berg. 2000. Biochemical interactions integrating Itk with the T cell receptor-initiated signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 275:2219-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunnell, S. C., D. I. Hong, J. R. Kardon, T. Yamazaki, C. J. McGlade, V. A. Barr, and L. E. Samelson. 2002. T cell receptor ligation induces the formation of dynamically regulated signaling assemblies. J. Cell Biol. 158:1263-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunnell, S. C., V. Kapoor, R. P. Trible, W. Zhang, and L. E. Samelson. 2001. Dynamic actin polymerization drives T cell receptor-induced spreading: a role for the signal transduction adaptor LAT. Immunity 14:315-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campi, G., R. Varma, and M. L. Dustin. 2005. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. J. Exp. Med. 202:1031-1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho, S., C. A. Velikovsky, C. P. Swaminathan, J. C. Houtman, L. E. Samelson, and R. A. Mariuzza. 2004. Structural basis for differential recognition of tyrosine-phosphorylated sites in the linker for activation of T cells (LAT) by the adaptor Gads. EMBO J. 23:1441-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.da Silva, A. J., Z. Li, C. de Vera, E. Canto, P. Findell, and C. E. Rudd. 1997. Cloning of a novel T-cell protein FYB that binds FYN and SH2-domain-containing leukocyte protein 76 and modulates interleukin 2 production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7493-7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Douglass, A. D., and R. D. Vale. 2005. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell 121:937-950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durand, D. B., J. P. Shaw, M. R. Bush, R. E. Replogle, R. Belagaje, and G. R. Crabtree. 1988. Characterization of antigen receptor response elements within the interleukin-2 enhancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:1715-1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang, N., D. G. Motto, S. E. Ross, and G. A. Koretzky. 1996. Tyrosines 113, 128, and 145 of SLP-76 are required for optimal augmentation of NFAT promoter activity. J. Immunol. 157:3769-3773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freiberg, B. A., H. Kupfer, W. Maslanik, J. Delli, J. Kappler, D. M. Zaller, and A. Kupfer. 2002. Staging and resetting T cell activation in SMACs. Nat. Immunol. 3:911-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grakoui, A., S. K. Bromley, C. Sumen, M. M. Davis, A. S. Shaw, P. M. Allen, and M. L. Dustin. 1999. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science 285:221-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hailman, E., W. R. Burack, A. S. Shaw, M. L. Dustin, and P. M. Allen. 2002. Immature CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes form a multifocal immunological synapse with sustained tyrosine phosphorylation. Immunity 16:839-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harder, T., and M. Kuhn. 2000. Selective accumulation of raft-associated membrane protein LAT in T cell receptor signaling assemblies. J. Cell Biol. 151:199-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houtman, J. C., Y. Higashimoto, N. Dimasi, S. Cho, H. Yamaguchi, B. Bowden, C. Regan, E. L. Malchiodi, R. Mariuzza, P. Schuck, E. Appella, and L. E. Samelson. 2004. Binding specificity of multiprotein signaling complexes is determined by both cooperative interactions and affinity preferences. Biochemistry 43:4170-4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huppa, J. B., M. Gleimer, C. Sumen, and M. M. Davis. 2003. Continuous T cell receptor signaling required for synapse maintenance and full effector potential. Nat. Immunol. 4:749-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irvin, B. J., B. L. Williams, A. E. Nilson, H. O. Maynor, and R. T. Abraham. 2000. Pleiotropic contributions of phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1) to T-cell antigen receptor-mediated signaling: reconstitution studies of a PLC-γ1-deficient Jurkat T-cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:9149-9161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krogsgaard, M., Q. J. Li, C. Sumen, J. B. Huppa, M. Huse, and M. M. Davis. 2005. Agonist/endogenous peptide-MHC heterodimers drive T cell activation and sensitivity. Nature 434:238-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krummel, M. F., and M. M. Davis. 2002. Dynamics of the immunological synapse: finding, establishing and solidifying a connection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:66-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krummel, M. F., M. D. Sjaastad, C. Wulfing, and M. M. Davis. 2000. Differential clustering of CD4 and CD3zeta during T cell recognition. Science 289:1349-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, K. H., A. R. Dinner, C. Tu, G. Campi, S. Raychaudhuri, R. Varma, T. N. Sims, W. R. Burack, H. Wu, J. Wang, O. Kanagawa, M. Markiewicz, P. M. Allen, M. L. Dustin, A. K. Chakraborty, and A. S. Shaw. 2003. The immunological synapse balances T cell receptor signaling and degradation. Science 302:1218-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, K. H., A. D. Holdorf, M. L. Dustin, A. C. Chan, P. M. Allen, and A. S. Shaw. 2002. T cell receptor signaling precedes immunological synapse formation. Science 295:1539-1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, J., M. J. Miller, and A. S. Shaw. 2005. The c-SMAC: sorting it all out (or in). J. Cell Biol. 170:177-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, J., and A. Weiss. 2001. Identification of the minimal tyrosine residues required for linker for activation of T cell function. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29588-29595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, S. K., N. Fang, G. A. Koretzky, and C. J. McGlade. 1999. The hematopoietic-specific adaptor protein gads functions in T-cell signaling via interactions with the SLP-76 and LAT adaptors. Curr. Biol. 9:67-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu, S. K., C. A. Smith, R. Arnold, F. Kiefer, and C. J. McGlade. 2000. The adaptor protein Gads (Grb2-related adaptor downstream of Shc) is implicated in coupling hemopoietic progenitor kinase-1 to the activated TCR. J. Immunol. 165:1417-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKeithan, T. W. 1995. Kinetic proofreading in T-cell receptor signal transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5042-5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mossman, K. D., G. Campi, J. T. Groves, and M. L. Dustin. 2005. Altered TCR signaling from geometrically repatterned immunological synapses. Science 310:1191-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musci, M. A., L. R. Hendricks-Taylor, D. G. Motto, M. Paskind, J. Kamens, C. W. Turck, and G. A. Koretzky. 1997. Molecular cloning of SLAP-130, an SLP-76-associated substrate of the T cell antigen receptor-stimulated protein tyrosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 272:11674-11677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Musci, M. A., D. G. Motto, S. E. Ross, N. Fang, and G. A. Koretzky. 1997. Three domains of SLP-76 are required for its optimal function in a T cell line. J. Immunol. 159:1639-1647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myung, P. S., G. S. Derimanov, M. S. Jordan, J. A. Punt, Q. H. Liu, B. A. Judd, E. E. Meyers, C. D. Sigmund, B. D. Freedman, and G. A. Koretzky. 2001. Differential requirement for SLP-76 domains in T cell development and function. Immunity 15:1011-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negulescu, P. A., T. B. Krasieva, A. Khan, H. H. Kerschbaum, and M. D. Cahalan. 1996. Polarity of T cell shape, motility, and sensitivity to antigen. Immunity 4:421-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Keefe, J. P., K. Blaine, M. L. Alegre, and T. F. Gajewski. 2004. Formation of a central supramolecular activation cluster is not required for activation of naive CD8+ T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:9351-9356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Keefe, J. P., and T. F. Gajewski. 2005. Cutting edge: cytotoxic granule polarization and cytolysis can occur without central supramolecular activation cluster formation in CD8+ effector T cells. J. Immunol. 175:5581-5585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purtic, B., L. A. Pitcher, N. S. van Oers, and C. Wulfing. 2005. T cell receptor (TCR) clustering in the immunological synapse integrates TCR and costimulatory signaling in selected T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:2904-2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raab, M., A. J. da Silva, P. R. Findell, and C. E. Rudd. 1997. Regulation of Vav-SLP-76 binding by ZAP-70 and its relevance to TCR zeta/CD3 induction of interleukin-2. Immunity 6:155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richie, L. I., P. J. Ebert, L. C. Wu, M. F. Krummel, J. J. Owen, and M. M. Davis. 2002. Imaging synapse formation during thymocyte selection: inability of CD3zeta to form a stable central accumulation during negative selection. Immunity 16:595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Routledge, E. J., R. White, M. G. Parker, and J. P. Sumpter. 2000. Differential effects of xenoestrogens on coactivator recruitment by estrogen receptor (ER) alpha and ERbeta. J. Biol. Chem. 275:35986-35993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samelson, L. E. 2002. Signal transduction mediated by the T cell antigen receptor: the role of adapter proteins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20:371-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sauer, K., J. Liou, S. B. Singh, D. Yablonski, A. Weiss, and R. M. Perlmutter. 2001. Hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 associates physically and functionally with the adaptor proteins B cell linker protein and SLP-76 in lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:45207-45216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seminario, M. C., P. Precht, S. C. Bunnell, S. E. Warren, C. M. Morris, D. Taub, and R. L. Wange. 2004. PTEN permits acute increases in D3-phosphoinositide levels following TCR stimulation but inhibits distal signaling events by reducing the basal activity of Akt. Eur. J. Immunol. 34:3165-3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singer, A. L., S. C. Bunnell, A. E. Obstfeld, M. S. Jordan, J. N. Wu, P. S. Myung, L. E. Samelson, and G. A. Koretzky. 2004. Roles of the proline-rich domain in SLP-76 subcellular localization and T cell function. J. Biol. Chem. 279:15481-15490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stauffer, T. P., and T. Meyer. 1997. Compartmentalized IgE receptor-mediated signal transduction in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 139:1447-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stefanova, I., B. Hemmer, M. Vergelli, R. Martin, W. E. Biddison, and R. N. Germain. 2003. TCR ligand discrimination is enforced by competing ERK positive and SHP-1 negative feedback pathways. Nat. Immunol. 4:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Straus, D. B., and A. Weiss. 1992. Genetic evidence for the involvement of the lck tyrosine kinase in signal transduction through the T cell antigen receptor. Cell 70:585-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valitutti, S., M. Dessing, K. Aktories, H. Gallati, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1995. Sustained signaling leading to T cell activation results from prolonged T cell receptor occupancy. Role of T cell actin cytoskeleton. J. Exp. Med. 181:577-584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson, B. S., J. R. Pfeiffer, and J. M. Oliver. 2000. Observing FcɛRI signaling from the inside of the mast cell membrane. J. Cell Biol. 149:1131-1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson, B. S., J. R. Pfeiffer, Z. Surviladze, E. A. Gaudet, and J. M. Oliver. 2001. High resolution mapping of mast cell membranes reveals primary and secondary domains of Fc(epsilon)RI and LAT. J. Cell Biol. 154:645-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu, J., D. G. Motto, G. A. Koretzky, and A. Weiss. 1996. Vav and SLP-76 interact and functionally cooperate in IL-2 gene activation. Immunity 4:593-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wunderlich, L., A. Farago, J. Downward, and L. Buday. 1999. Association of Nck with tyrosine-phosphorylated SLP-76 in activated T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:1068-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yablonski, D., T. Kadlecek, and A. Weiss. 2001. Identification of a phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1) SH3 domain-binding site in SLP-76 required for T-cell receptor-mediated activation of PLC-γ1 and NFAT. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4208-4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokosuka, T., K. Sakata-Sogawa, W. Kobayashi, M. Hiroshima, A. Hashimoto-Tane, M. Tokunaga, M. L. Dustin, and T. Saito. 2005. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat. Immunol. 6:1253-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zacharias, D. A., J. D. Violin, A. C. Newton, and R. Y. Tsien. 2002. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science 296:913-916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zal, T., M. A. Zal, and N. R. Gascoigne. 2002. Inhibition of T cell receptor-coreceptor interactions by antagonist ligands visualized by live FRET imaging of the T-hybridoma immunological synapse. Immunity 16:521-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang, W., R. P. Trible, M. Zhu, S. K. Liu, C. J. McGlade, and L. E. Samelson. 2000. Association of Grb2, Gads, and phospholipase C-gamma 1 with phosphorylated LAT tyrosine residues. Effect of LAT tyrosine mutations on T cell antigen receptor-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23355-23361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.