Abstract

Infected aneurysms caused by Yersinia are very uncommon and are principally due to Yersinia enterocolitica. We describe the first case of an infected aneurysm caused by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis in an elderly patient with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

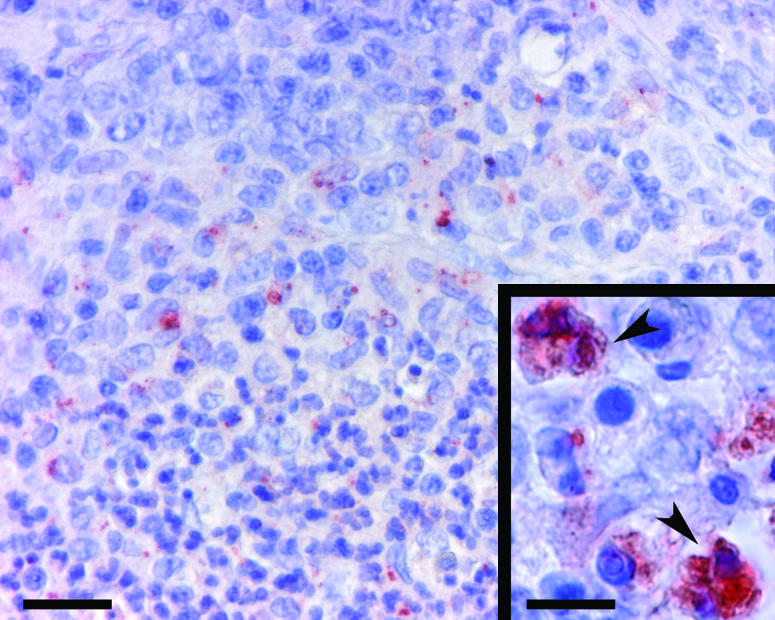

In January 2005, a 64-year-old man who had previously been a chronic smoker and who had a history of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and myocardial infarction was admitted to the Centre Hospitalier et Universitaire de Nancy for persistent abdominal pain with intermittent fever. During the preceding 3 weeks he had experienced recurrent episodes of pain of the right iliac fossa, with intermittent shivers and progressive weight loss (7 kg). Therefore, an abdominal ultrasonography as well as an abdominal and thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan were performed and revealed the presence of an important abdominal aortic aneurysm with abnormal contours associated with multiple other atheromatous vascular lesions and a steatosic hepatomegaly. On admission to the hospital, the patient was apyretic, slightly disoriented, and constipated and had a blood pressure of 140/70 mm Hg. Abdominal examination was normal except for moderate hepatomegaly and tenderness of the right iliac fossa. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 10,300 cells/mm3 (62% polymorphonuclear leukocytes); an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 110/113 mm; a C-reactive protein level of 157 mg/liter; and elevated aspartate aminotransferase (112 IU/liter), alanine aminotransferase (102 IU/liter), and gamma-glutamyltransferase (653 IU/liter) levels. An abdominal CT scan showed the presence of a fissured infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm. Surgery was performed on the same day. An aneurysm measuring approximately 8 cm in diameter that had ruptured into the retroperitoneal space was resected, and aortic tissue samples were sent for bacteriological analysis. Several enlarged adjacent lymph nodes were discovered and sent for histological analysis. After debridement of all surrounding inflammatory tissues, an aortoaortic bypass graft was accomplished by using a Dacron straight graft. Histological examination of the lymph nodes showed a granulomatous and slightly necrotizing lymphadenitis with microabscesses. No bacteria were observed in any of the Gram-stained preparations of the aorta examined. After 24 h of incubation, chocolate agar and brain heart infusion broth yielded the growth of a gram-negative bacillus that was identified as Yersinia pseudotuberculosis by using the API 20E system and the Vitek 2 GNI card/4.01 software version (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) with 99.9% and 91.22% accuracies, respectively. This isolate was subsequently shown to belong to Y. pseudotuberculosis serotype O:I (9). Subsequent immunohistochemical examination of the lymph nodes showed the presence of phagocyte-associated, probably intracellular, Y. pseudotuberculosis (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemical staining of lymph node sections was performed by standard procedures with antiserum specific for Y. pseudotuberculosis type I, generated in the French Reference Center for Yersinia. Briefly, after incubation of the lymph node sections with the Y. pseudotuberculosis-specific antiserum, detection was conducted with Envision System HRP (DakoCytomation) and the organism was revealed with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole. The slides were counterstained with hemalun (14). Antibiotic susceptibility was determined by the disk diffusion method, as recommended by the Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie (3). The organism was found to be susceptible to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, rifampin, fosfomycin, and minocycline and resistant to colistin. The patient was given ceftriaxone (1 g once a day) and ciprofloxacin (0.2 g three times a day) intravenously. The outcome was favorable, and the patient was discharged in good health 17 days later. Subcutaneous ceftriaxone (1 g once a day) and oral ofloxacin (0.2 g twice a day) were then given for an additional 10 days.

FIG. 1.

Phagocyte-associated Y. pseudotuberculosis. Immunohistochemical staining was performed with a specific antibody for Y. pseudotuberculosis type I. Stained bacteria appear reddish (Envision System HRP) among hemalun-stained blue phagocytic cells. A partial view of an inflammatory focus of a lymph node composed of a core of polynuclear phagocytes (lower half of the photograph) surrounded by macrophages (upper half) is shown. Bar, 25 μm. (Inset) closer view of bacteria associated with phagocytes (arrowheads). Bar, 10 μm.

Discussion.

Bacteria commonly involved in infections of atherosclerotic aneurysms include Staphylococcus aureus; Streptococcus pneumoniae; nonhemolytic streptococci; Salmonella spp.; and other gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Campylobacter spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Bacteroides spp. (7, 8). Vascular infections involving Yersinia spp. are very uncommon. In humans, only a few cases of arterial aneurysm infections, vascular graft infections after aneurysm repair, or endocarditis have been reported to have been caused by Y. enterocolitica (4-6, 11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19-21). Vascular infections involving Y. pseudotuberculosis have not yet been reported. It has only been suggested that Y. pseudotuberculosis may play a role in the pathogenesis of Kawazaki disease (2, 11), but this still remains uncertain.

Septic embolization secondary to bacterial endocarditis or infection from a contiguous site may be involved in the pathogenesis of aneurysm infection. However, most infected aneurysms result from hematogenous colonization of structurally altered arteries during bacteremia. Our patient had an existing abdominal aortic aneurysm that was most likely infected secondarily by Y. pseudotuberculosis following the pseudoappendicitis episode that he had experienced 3 weeks earlier, although this was not documented, since cultures of stool and blood specimens had not been performed at that time. Endocarditis was ruled out by echocardiography; however, it remains unclear whether the aneurysm became infected by hematogenous seeding or by contiguous extension from infected lymph nodes.

Y. pseudotuberculosis is found in numerous wild and domestic mammals and may also survive in soil and water (1). Infections caused by this organism in humans are mainly acquired through the gastrointestinal tract as a result of the consumption of contaminated food, water, or even milk (1, 17). Our patient used to drink nonpasteurized milk, which may have represented a means of contamination. Y. pseudotuberculosis primarily causes mesenteric lymphadenitis and, more rarely, terminal ileitis and enteritis. Mesenteric infections are mostly self-limited and need no specific treatment except in patients with underlying conditions, such as diabetes, cirrhosis, malignancy, immunodeficiency, and iron overload, which may favor the systemic diffusion of the infection (1, 12). Such conditions were not found in our case, although they have been found in cases of arterial aneurysms infected by Y. enterocolitica (5, 10, 16). The use of antibiotic therapy during the pseudoappendicitis episode might have prevented aneurysm infection and further rupture; however, no rationale for such prophylaxis exists and further investigations are needed to clarify this question.

In conclusion, this is the first report of an aneurysm infection caused by Y. pseudotuberculosis, which should also be considered an etiological agent of infected aneurysms even in patients with no predisposing factors for systemic infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michel Huerre and Patrick Avé for their assistance with the immunohistochemical aspects of this case.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bockenmühl, J., and J. D. Wong. 2003. Yersinia, p. 672-683. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 8th ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Chou, C. T., J. S. Chang, S. E. Ooi, A. P. Huo, S. J. Chang, H. N. Chang, and C. Y. Tsai. 2005. Serum anti-Yersinia antibody in Chinese patients with Kawasaki disease. Arch. Med. Res. 36:14-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie. 2005. Communiqué 2005. Société Française de Microbiologie, Paris, France.

- 4.Donald, K., J. Woodson, H. Hudson, and J. O. Menzoian. 1996. Multiple mycotic pseudoaneurysms due to Yersinia enterocolitica: report of a case and review of the literature. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 10:573-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagensee, M. E. 1994. Mycotic aortic aneurysm due to Yersinia enterocolitica. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:801-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haissaguerre, M., J. J. Douvier, J. Bonnet, M. Heraudeau, H. Bricaud, and P. Besse. 1984. Myocardiopathie réversible associée à une yersiniose. Sem. Hop. Paris 60:1433-1436. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu, R. B., R. J. Chen, S. S. Wang, and S. H. Chu. 2004. Infected aortic aneurysms: clinical outcome and risk factor analysis. J. Vasc. Surg. 40:30-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearney, R. A., H. J. Eisen, and J. E. Wolf. 1994. Non valvular infections of the cardiovascular system. Ann. Intern. Med. 121:219-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knapp, W. 1960. On further antigen relations between Pasteurella pseudotuberculosis and the Salmonella group. Z. Hyg. Infectionskr. 146:315-330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konishi, N., K. Baba, J. Abe, T. Maruko, K. Waki, N. Takeda, and M. Tanaka. 1997. A case of Kawasaki disease with coronary artery aneurysms documenting Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection. Acta Paediatr. 86:661-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Scola, B., D. Musso, A. Carta, P. Piquet, and J. P. Casalta. 1997. Aortoabdominal aneurysm infected by Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:9. J. Infect. 35:314-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ljungberg, P., M. Valtonen, V. P. Harjola, S. S. Kaukoranta-Tolvanen, and M. Vaara. 1995. Report of four cases of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis septicaemia and a literature review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14:804-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercie, P., P. Morlat, A. N′Gako, P. Pheline, M. C. Bezian, G. Gorin, D. Lacoste, N. Bernard, I. Loury, D. Midy, J. C. Baste, and J. Beylot. 1996. Aortic aneurysms due to Yersinia enterocolitica: three new cases and a review of the literature. J. Mal. Vasc. 21:68-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naish, S. J. (ed.). 1989. Handbook—immunochemical staining methods. DAKO Cytomation, Carpinteria, Calif.

- 15.Plotkin, G. R., and J. N. O'Rourke, Jr. 1981. Mycotic aneurysm due to Yersinia enterocolitica. Am. J. Med. Sci. 281:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prentice, M. B., N. Fortineau, T. Lambert, A. Voinnesson, and D. Cope. 1993. Yersinia enterocolitica and mycotic aneurysm. Lancet 341:1535-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prober, C. G., B. Tune, and L. Hoder. 1979. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis septicaemia. Am. J. Dis. Child. 133:623-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tame, S., D. de Wit, and A. Meek. 1998. Yersinia enterocolitica and mycotic aneurysm. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 68:813-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Noyen, R., P. Peeters, F. van Dessel, and J. Vandepitte. 1987. Mycotic aneurysm of the aorta due to Yersinia enterocolitica. Contrib. Microbiol. Immunol. 9:122-126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Steen, J., J. Vercruysse, G. Wilms, and A. Nevelsteen. 1989. Arteriosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysm infected with Yersinia enterocolitica. RoFo 151:625-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verhaegen, J., G. Dedeyne, W. Vansteenbergen, and J. Vandepitte. 1985. Rupture of the vascular prosthesis in a patient with Yersinia enterocolitica bacteremia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 3:451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]