Abstract

We developed an internal positive control (IPC) RNA to help ensure the accuracy of the detection of avian influenza virus (AIV) RNA by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR and real-time RT-PCR (RRT-PCR). The IPC was designed to have the same binding sites for the forward and reverse primers of the AIV matrix gene as the target amplicon, but it had a unique internal sequence used for the probe site. The amplification of the viral RNA and the IPC by RRT-PCR were monitored with two different fluorescent probes in a multiplex format, one specific for the AIV matrix gene and the other for the IPC. The RRT-PCR test was further simplified with the use of lyophilized bead reagents for the detection of AIV RNA. The RRT-PCR with the bead reagents was more sensitive than the conventional wet reagents for the detection of AIV RNA. The IPC-based RRT-PCR detected inhibitors in blood, kidney, lungs, spleen, intestine, and cloacal swabs, but not allantoic fluid, serum, or tracheal swabs The accuracy of RRT-PCR test results with the lyophilized beads was tested on cloacal and tracheal swabs from experimental birds inoculated with AIV and compared with virus isolation (VI) on embryonating chicken eggs. There was 97 to 100% agreement of the RRT-PCR test results with VI for tracheal swabs and 81% agreement with VI for cloacal swabs, indicating a high level of accuracy of the RRT-PCR assay. The same IPC in the form of armored RNA was also used to monitor the extraction of viral RNA and subsequent detection by RRT-PCR.

Avian influenza (AI) is an important disease in poultry that is caused by an RNA virus of the family Orthomyxoviridae (25). Wild birds, including waterfowl and shorebirds, are the natural reservoirs of AI viruses (AIV), and yet they typically show no clinical symptoms of infection (34-36). The AI viruses can cross species barrier to infect a variety of animals, including humans, pigs, horses, sea mammals, mustelids, and domestic poultry (3, 32, 38, 41). Based on the antigenic profiles of the surface glycoproteins, hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, AI viruses have been classified into 16 hemagglutinin subtypes (H1 through H16) and 9 neuraminidase subtypes (N1 through N9) (16, 36). Based on their abilities to cause clinical disease, AI viruses are further classified into two distinct groups, low-pathogenicity avian influenza viruses and highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses.

The highly pathogenic avian influenza virus causes a systemic disease with rapid death in chickens and turkeys, often reaching 100% mortality, leading to severe economic losses during outbreaks (17, 21, 23, 35, 36). Therefore, routine surveillance and early detection of the virus are keys to the control, management, and eradication of the disease. Many molecular-biology-based techniques are available for the rapid detection of AIV in clinical samples (7, 8, 11, 15, 26, 33, 37). Real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RRT-PCR) has been widely adopted in the United States and other countries because it is sensitive and rapid, it can be performed with high-throughput methods, and it has less potential for cross contamination than traditional RT-PCR (26, 40). However, one concern with any of the molecular diagnostic methods is the potential for false-negative results. A false-negative result may occur from multiple causes, including the presence of RT-PCR inhibitors, poor target RNA recovery during extraction, degradation of target RNA before amplification, errors in setting up a reaction, or a degraded reagent (2, 18, 20, 24, 39). Therefore, the presence of an internal positive control (IPC) in each sample would be useful to monitor the RRT-PCR procedure and to ensure that the test was performed correctly. Applications of different types of IPCs in RRT-PCR assays have been developed for testing clinical specimens. The IPCs can be competitive or noncompetitive with the target template. A competitive IPC uses a mimic design in which the same primer binding sites are used but the internal sequence has been altered so that it can be differentiated from the target sequence either by size or by differential probes. Noncompetitive IPC, however, uses a completely separate target that does not directly compete with the target amplicon and has a different set of primers and probe not shared with the target amplicon for its amplification. The IPC for RRT-PCR can be introduced in a variety of ways, including transcribed RNA, armored RNA, inactivated virus, or plasmid DNA (1, 6, 9, 10, 12, 14, 19, 27, 28, 31). In all cases, the IPC can be monitored in the same reaction by resolving the products on an agarose gel or using different fluorescent probes in a multiplex format with RRT-PCR. Alternatively, the IPC can be used in a duplicate reaction to determine if PCR inhibitors are present, but this approach doubles the cost of each reaction and does not detect if user errors have occurred.

Previously, we reported on the RRT-PCR diagnostics of AIV based on the amplification of the matrix gene (33). In this study, we modified the previously reported RRT-PCR procedure by including an IPC in the assay and using lyophilized RRT-PCR master mixture with a different RT-PCR buffer. The IPC used in this study was a 228-base-long RNA that was in vitro transcribed from a DNA template. The same IPC in the form of armored RNA (phage-packaged IPC) (12) was used in samples containing virus to monitor the RNA extraction step, as well as the RRT-PCR amplification step. The results showed improved detection of AIV RNA with lyophilized reagents; in addition, the presence of IPC in the RRT-PCR master mixture helped to identify the samples that were likely to contain RT-PCR inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

AI viruses and RNA extraction from the virus.

Fifteen subtypes of AIV (H1 through H15) were used in this study. Viral RNA was extracted with Trizol LS (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), a QIAmp viral-RNA minikit (QV), or a QIAmp RNeasy minikit (QR) (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Extracted RNA was eluted in 60 μl of RNase-free water and stored at −70°C for long-term use and at −20°C for short-term use. RNA was diluted with RNase-free water as needed.

Manipulation of DNA and RNA.

Restriction digestion of DNA and the agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA were carried out by standard protocols (30). The ligation and cloning of DNA fragments were carried out with T4 DNA ligase from Promega (Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For RNA gel electrophoresis, RNA was denatured with glyoxal prior to electrophoresis under the conditions described previously (5).

Preparation of internal positive control RNA.

The IPC RNA used in this study was in vitro transcribed from a DNA template using T7 RNA polymerase. The IPC DNA template was constructed from three pairs of custom-designed oligonucleotide primers, each consisting of one positive and one complementary negative strand of the same primer, so that they could be annealed into a double-stranded DNA fragment. The first pair (pair 1) consisted of IPC-Matrix Forward (+), tcgaGAGTGATGTGCTCGGACCTTCGGTGAGTCTATCCGGAGGATACAAGGAGATGAGTCTTCTAACCGAGGTCGAA, and IPC-Matrix Forward (−), CTCACTACACGAGCCTGGAAGCCACTCAGATAGGCCTCCTATGTTCCTCTACTCAGAAGATTGGCTCCAGCTTgcgc; the second pair (pair 2) consisted of IPC-Probe (+), cgcgTATGCAGGTGAGGACATCCAGCTACGGGGCAAGTGCAATAGAGGGCTCTCCAGAACATCATCCCTGCCTT, and IPC-Probe (−), ATACGTCCACTCCTGTAGGTCGATGCCCCGTTCACGTTATCTCCCGAGAGGTGTCTTGTAGTAGGGGACGGAAgatc; and the third pair (pair 3) consisted of IPC-Matrix reverse (+), ctagTAGATCTTAGCAAATGCCTCTCCTCAGGCTTGGGGTTGCAACAGCTCAGAGACTTGAAGATGTTTTTGCAG, and IPC-Matrix reverse (−), ATCTAGAATCGTTTACGGAGAGGAGTCCGAACCCCAACGTTGTCGAGTCTCTGAACTTCTACAAAAACGTCagct. The primers were designed to have binding sites for the AIV matrix forward (AI M + 25, AGATGAGTCTTCTAACCGAGGTCG) and AIV matrix reverse (AI M-124, TGCAAAAACATCTTCAAGTCTCTG) (33) in the IPC-Matrix forward (+) and IPC-Matrix reverse (−) primers, respectively, described above. The complementary primers from each pair were denatured at 90°C for 30 min and annealed by cooling them at room temperature (25°C). The primers were designed in such a way that, after annealing, each DNA fragment would have protruding unpaired sequences (the lowercase letters at either the 5′ or 3′ end of each primer) complementary to unique restriction sites (sticky ends) at both the 5′ and 3′ ends. Thus, DNA fragment I (the annealed product from pair 1 oligonucleotides) had an XhoI restriction site at the 5′ end and an MluI site at the 3′ end, DNA fragment II (the annealed product from pair 2 oligonucleotides) had an MluI site at the 5′ end and an XbaI site at the 3′ end, and DNA fragment III (the annealed product from pair 3 oligonucleotides) had an XbaI at the 5′ end and a SalI site at the 3′ end. DNA fragment I and DNA fragment II were ligated at the MluI site to generate DNA fragment IV (Fig. 1). Then, DNA fragment III with an XbaI site at the 5′ end was ligated to the 3′ XbaI site of DNA fragment IV to generate the IPC template. In the final step, the IPC template with a 5′ XhoI site and a 3′ SalI site was cloned into the corresponding restriction sites at the multiple cloning sites of the plasmid pCI to generate pMFM. The nucleotide sequence of the cloned IPC template derived from pMFM matched the nucleotide sequences of the oligonucleotide primers used to construct the IPC template and was 228 bases long (Fig. 2). The nucleotide sequence corresponding to the AIV matrix forward (AI M + 25) and reverse (AI M-124) primers were located between nucleotides 53 and 75 on the plus strand and between nucleotides 200 and 223 on the minus strand of the template, respectively (Fig. 2). Upon amplification with the above-mentioned primers, the IPC template yielded a PCR product of 177 bp and the viral RNA yielded a PCR product of 100 bp, so the products could be easily distinguished after electrophoresis on an agarose gel.

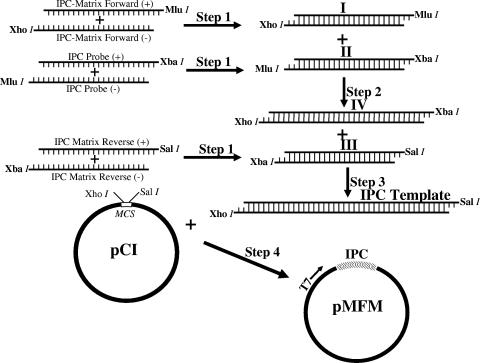

FIG. 1.

Construction and cloning of the DNA template for the IPC. (Step 1) Annealing. Complementary pairs of oligonucleotide primers IPC-Matrix forward (+) and IPC-Matrix forward (−) (pair 1), IPC-Probe (+) and IPC-Probe (−) (pair 2), and IPC-Matrix Reverse (+) and IPC-Matrix Reverse (−) (pair 3) were denatured at 90°C for 30 min and annealed at room temperature to generate double-stranded DNA fragments I, II, and III, respectively. (Steps 2 and 3) Ligation. Double-stranded DNA fragments I and II were ligated at the MluI site to generate double-stranded fragment IV (step 2), and the double-stranded fragment IV was ligated to double-stranded fragment III at the XbaI site to generate the IPC template (step 3). (Step 4) Cloning. The IPC template with 5′ XhoI and 3′ SalI sticky ends was ligated to the corresponding sites at the multiple cloning site of the plasmid pCI. See Materials and Methods for details of the steps.

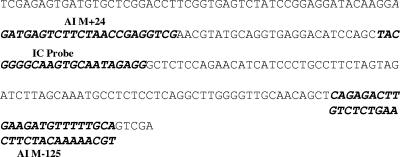

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the IPC template derived from pMFM. The nucleotide sequences in boldface italics represent the AIV matrix forward primer, the AIV matrix reverse primer, and the IPC probe.

In vitro transcription of the AIV matrix and the IPC RNA and determination of the minimum detection level by RRT-PCR.

The AIV matrix RNA was in vitro transcribed from the corresponding DNA template cloned into a plasmid vector as described previously (33). The IPC RNA was in vitro transcribed from either pMFM or PCR product and amplified from pMFM with matrix primers modified to include the promoter site on the 5′ end by T7 RNA polymerase from the RiboMAX large-scale RNA production system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The IPC RNA generated from the above-mentioned reaction was treated with RNase-free DNase I (supplied with the RiboMAX system) and tested for purity by both RNA gel electrophoresis and PCR testing prior to use in RT-PCR and RRT-PCR experiments. The purified IPC RNA was suspended in RNase-free Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) and stored at −70°C in aliquots at a concentration of 480 fg/μl. To determine the minimum detection level (MDL) for RRT-PCR, the AIV matrix and IPC RNAs were serially diluted with RNase-free water prior to use in the assay.

Armored RNA and the MDL.

The armored RNA (Ambion, Austin, TX) used in this study contained the same IPC RNA (228 bases), but it was packaged within bacteriophage coat proteins (12) prepared by Ambion RNA Diagnostics (Austin, TX). It was supplied at a concentration of 0.25 mg/ml, with each mg containing approximately 1.9 × 1014 copies of RNA. For working stock, it was diluted to 4.75 × 1010 copies RNA per μl with brain hearth infusion broth (BHI) and stored at 4°C. Armored RNA was extracted with Trizol LS (Invitrogen), QV, and QR according to the manufacturers' instructions. To determine the MDL, the armored RNA was serially diluted with BHI up to 1010 dilutions, and 140 μl of suspension from each dilution was used for RNA extraction. One hundred forty microliters of suspension was directly used for extraction with QV, while it was diluted to 250 μl with BHI for extraction with Trizol or QR. The extracted RNA was dissolved in 60 μl of RNase-free water, and 8 μl was used per 25 μl of reaction mixture for RRT-PCR.

RT-PCR and RRT-PCR with the QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR kit.

The QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR kit was previously used for the detection of AIV by RRT-PCR in our laboratory (33), and the protocol was designed to amplify the AIV matrix gene with AI M + 25 as the forward primer, AI M-124 as the reverse primer, and M-64 as the internal probe. The composition of the master mixture and the thermocycling conditions for RT-PCR and RRT-PCR were as described previously (33). Briefly, the master mixture (50 μl) for RT-PCR included 10 μl of QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR 5× buffer (final concentration, 1×), 2 μl of kit-supplied enzyme mixture, 10 pmol each of forward (AI M + 25) and reverse (AI M-124) primers (0.5 μl), 2 μl of kit-supplied deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mixture (10 mM each of dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP), 13 units of RNase inhibitor (RNaisin; Promega), 8 μl of viral-RNA template, and RNase-free water to adjust the volume to 50 μl. The master mixture (25 μl) for RRT-PCR included 1 μl of enzyme mixture, 0.5 μl of RNase inhibitor (6.5 units; Promega), 3.75 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of forward (AI M + 25) and reverse (AI M-124) primers, 0.8 μl of dNTP mixture (10 mM stock or 320 μM each of dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP), 3 pmol each of AIV matrix probe AI M + 64 (33) labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coraville, IA) and the IPC probe (CAL Fluor Red 610 [TACGGGGCAAGTGCAATAGAGG-black hole quencher-2]) labeled with CalFluor 610 (Integrated DNA Technologies), 6.95 μl RNase-free water, 8 μl of viral-RNA template, and a calculated amount of the IPC RNA (see below). The thermocycling conditions for RT-PCR included one cycle of RT at 50°C for 30 min; followed by heat activation of hot-start Taq polymerase at 95°C for 15 min and 32 cycles of PCR amplification, with each cycle consisting of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 45 s of annealing at 51°C, and 45 s of elongation at 72°C; and one final cycle of elongation at 72°C for 10 min. The thermocycling conditions for RRT-PCR included the same RT step and Taq activation step as for RT-PCR plus 40 cycles of PCR amplification, with each cycle consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 s and annealing/elongation at 60°C for 20 s. The RT-PCR was carried out with a GeneAmp PCR System 2700 from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), and the RRT-PCR was carried out with a SmartCyler II (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA). All RRT-PCR results reported in this study are the averages of two or more replicates.

RRT-PCR with lyophilized reagents.

In an effort to develop lyophilized reagents for the RRT-PCR test, preliminary testing was performed with Cepheid's (Sunnyvale, CA) LyoBuffer or LyB (50 mM HEPES and 30 mM KCl, pH 8.0) (4, 13, 29) replacing the QIAGEN OneStep 5× buffer. The optimized reaction conditions for RRT-PCR with LyB included a master mixture (25-μl final volume) consisting of LyB, 4 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol AI M+25, 10 pmol AI M-124, 3 pmol AI M+64, 0.8 μl (10 mM stock) dNTP mixture, 1 μl enzyme mixture (QIAGEN OneStep), 0.5 μl (6.5 units) RNase inhibitor, 8 μl RNA template, and RNase-free water to adjust the final volume to 25 μl. The thermocycling conditions for RRT-PCR with LyB remained the same as described above, except the denaturation time of the PCR cycle increased from 1 s to 20 s.

Multiplex RRT-PCR of AIV RNA with lyophilized reagents containing the IPC.

All the components of the LyB RRT-PCR master mixture, along with the IPC and the IPC probe but without the enzymes (RNase and QIAGEN RT-PCR enzyme mixture) and dNTPs, were lyophilized into a bead format (Smartbeads; Cepheid Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). The amount of IPC probe used per reaction (25 μl) was 3 pmol, and the amount of IPC RNA in the beads was determined based on the MDL of the IPC as described in Results below. The composition of the LyB RRT-PCR master mixture was adjusted so that each bead was equivalent to four 25-μl reaction mixtures and the final reconstituted volume (68 μl) had the following composition: LyB (50 mM HEPES and 30 mM KCl, pH 8.0), 4 mM MgCl2, 40 pmol AI M + 24, 40 pmol AI M-125, 12 pmol AI M + 64 probe, 12 pmol IPC probe, and a calculated amount of the IPC. To reconstitute the mixture, 58.8 μl of RNase-free water, 3.2 μl of dNTP mixture (QIAGEN), 4 μl of QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR enzyme mixture, and 2 μl (26 units) of RNase inhibitor (Promega) were added to each bead, giving a final volume of the reaction mixture of 68 μl, 17 μl of which was distributed into each of four SmartCycler tubes. The viral-RNA template (8 μl) was added next, and the RRT-PCR was carried out under the conditions described above. During RRT-PCR, the amplification of the target template was monitored in the FAM channel and that of the IPC was monitored in the Texas Red channel using the Smartcycler II real-time PCR machine (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA).

The LyB master mixture with the composition described above was also used for the detection of armored RNA by RRT-PCR under the same thermocycling conditions used for the detection of the IPC (see above).

Detection of AIV in samples from experimentally infected chickens by multiplex RRT-PCR.

All samples used in this study were from 3- to 4-week-old White Plymouth Rock chickens inoculated with AI viruses of different subtypes. The samples include oropharyngeal swabs from chickens inoculated with A/Chicken/Queretaro/14588-19/95 (H5N2) collected 3, 6, and 8 days postinoculation (p.i.); tracheal and cloacal swabs of birds inoculated with A/chicken/TX/298313/04 (H5N2) collected 3 days p.i. (23); and cloacal swabs of birds inoculated with A/chicken/NJ/150383/02 (H7N2) collected 3 days p.i. (22). The samples from the last two experiments were also tested for the presence of AIV by virus isolation (VI) (22, 23), and the results were kindly provided by Chang-Won Lee. All swabs were suspended in 1.5 ml of BHI and extracted with an RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) or Trizol LS as indicated. The RNA was dissolved in 60 μl of RNase-free water and analyzed by multiplex RRT-PCR with AIV matrix lyophilized beads. The RRT-PCR assays for the detection of AIV with lyophilized beads had been validated by testing various clinical and test samples, and a cutoff cycle threshold (CT) value of 35 was assigned for all AIV-positive samples, while the samples having CTs higher than 35 were considered to be suspect and therefore were subjected to further evaluations, including VI.

Detection of RT-PCR inhibitors in various test samples from wild birds and chickens.

The presence of RT-PCR inhibitors was tested for in blood, serum, kidney, lungs, spleen, intestine, cloacal swabs, oropharyngeal swabs, and chicken egg allantoic fluid. All samples were collected from specific-pathogen-free chicken flocks maintained at the Southeast Poultry Research Laboratory (SEPRL), except for some cloacal swabs from wild birds, which were sent to SEPRL for testing for AIV. The wild-bird cloacal swabs that tested negative for AIV by virus isolation were pooled as a representative sample group that was spiked with known amounts of AI virus. Tissues from lungs, kidney, spleen, and intestine were minced with a razor blade and washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before being suspended in PBS to a final concentration of 10% (wet weight/volume). Whole blood was washed with sterile PBS before being resuspended in PBS to a final concentration of 10% (vol/vol). One-hundred-microliter amounts of all test samples (see above) were spiked with 40 μl of viral suspensions (50% egg infective dose, 106/ml), the volumes were adjusted to 250 μl with sterile PBS, and then they were extracted with Trizol. The extracted RNA was dissolved in 60 μl of RNase-free water, and 8 μl was used per reaction (RRT-PCR).

RESULTS

Preparation of the IPC and armored RNA and determination of MDL by RRT-PCR.

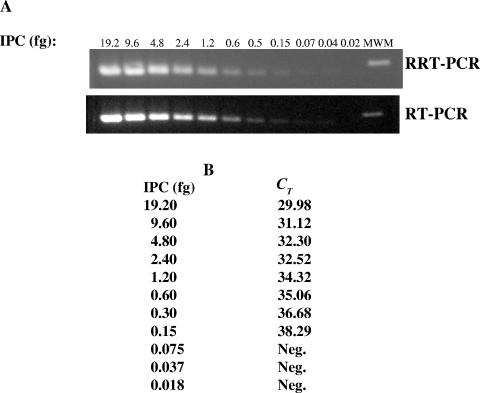

The construction of the IPC DNA template (Fig. 1), in vitro transcription of the IPC RNA from the DNA template, and preparation of armored RNA from the IPC RNA were described in Materials and Methods. The MDLs of the IPC and the armored RNAs for RRT-PCR were determined after serial dilution of the templates with RNase-free water. The MDL of the IPC RNA was determined to be 0.15 fg, or 1,227 copies per reaction, for both RRT-PCR and RT-PCR (Fig. 3). The MDL of the armored RNA varies depending on the yields of RNA from different methods of RNA extraction. The best yield of armored RNA was achieved with Trizol LS, followed by QV and QR (Table 1). Based on the copy number of the armored RNA in each dilution (derived from the number of copies in undiluted stock), the MDL was determined to be 887 copies (CT, 36.90) with RNA extracted by Trizol, 8,870 copies (CT, 36.98) with RNA extracted by QV, and 88,700 copies (CT, 36.26) with RNA extracted by QR.

FIG. 3.

MDL of the IPC determined by RT-PCR and RRT-PCR. (A) Gel electrophoresis of the PCR products amplified from serial dilutions of the IPC after RRT-PCR and RT-PCR. The amounts of IPC used per reaction were as shown. The DNA band (∼100 bp) in the far right lane belongs to the DNA molecular weight marker (MWM). (B) CTs corresponding to each amount of the IPC determined by RRT-PCR. Neg., negative.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of different methods for extraction of RNA from phage-packaged IPC (armored RNA)a

| Dilution (armored RNA) | Avg CT

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trizol LS | QV | QA | |

| 10−1 | 14.84 | 18.28 | |

| 10−2 | 14.21 | 16.11 | 20.94 |

| 10−3 | 17.66 | 19.77 | 24.96 |

| 10−4 | 20.40 | 23.56 | 29.34 |

| 10−5 | 24.23 | 27.99 | 32.92 |

| 10−6 | 27.58 | 30.13 | 36.26 |

| 10−7 | 30.74 | 33.86 | Negative |

| 10−8 | 33.63 | 36.98 | Negative |

| 10−9 | 35.90 | Negative | Negative |

| 10−10 | Negative | Negative | Negative |

RNA was extracted by Trizol LS, QV, and QR as described in Material and Methods. The CT corresponding to the armored RNA extracted by Trizol from 10−1 dilution was too high and out of the detectable range manually set for the SmartCycler.

The stabilities of the IPC and armored RNAs were tested based on the changes in the CTs under different storage conditions. The IPC RNA was stable for at least 6 months when stored in Tris-EDTA buffer at −80°C. In the same period (6 months), the IPC RNA was partially degraded (the CTs increased by less than one cycle) by storage at −20°C and slightly more (the CTs increased by one or two cycles) by storage at 4 to 10°C (results not shown). In comparison, the armored RNA was stable for 6 months in BHI with little change in the CTs from storage at 4 to 10°C.

MDL of AIV matrix RNA by multiplex RRT-PCR in the presence or absence of IPC using LyB.

We first compared the performances of LyB and QIAGEN OneStep 5× RT-PCR buffers to determine the sensitivity of detection and the detection limits of AIV RNA from 10-fold serial dilutions of the template. The average CT corresponding to each dilution of the AIV RNA was found to be more than 2 units lower with LyB than with the QIAGEN 5× buffer (not shown), indicating higher sensitivity of detection with LyB. The LyB master mixture was therefore used in all subsequent RRT-PCR assays. Table 2 shows the detection limits of an in vitro-transcribed AIV matrix RNA in the presence or absence of the IPC RNA. The MDL of AIV matrix RNA was shown to be 200 copies (CT, 37.59) (Table 2) in the absence of the IPC, which is fivefold more sensitive than the detection limit of 1,000 copies per reaction previously reported (33). The higher sensitivity of detection of the matrix RNA could be due to the LyB buffer and the different assay conditions used in this study, as described above. To determine the amount of IPC that minimally interfered with the detection of AIV matrix RNA by RRT-PCR in a multiplex format, serially diluted matrix RNA (2 × 106 to 2 × 102 copies) was subjected to RRT-PCR in the presence of various fixed amounts of IPC at concentrations higher than its MDL of 0.15 fg (0.5 fg to 32 fg per reaction). The IPC at the above concentrations had little effect on the detection of matrix RNA at or above 2 × 107 copies per reaction (not shown). The MDL of the matrix RNA was determined to be 2 × 106 copies (CT, 32.82) in the presence of 64 fg IPC/reaction, 2 × 105 copies (CTs, 34.44 to 34.88) in the presence of 8 to 32 fg IPC, 2 × 102 to 2 × 103 copies (CTs, 37.12 to 37.44) in the presence of 2 to 4 fg IPC, and 2 × 102 copies (CTs, 37.47 to 37.87) in the presence of 0.5 to 1 fg/reaction of the IPC (see Table 4). Matrix RNA at 2 × 102 copies per reaction was either undetectable or detectable at higher CTs (above 38) in the presence of 2 to 4 fg of IPC. The IPC at 0.5 to 2 fg/reaction minimally interfered with the detection of matrix RNA. The average CTs corresponding to the IPC at 0.5 to 2 fg per reaction in the matrix RNA-IPC multiplex RRT-PCR were determined to be 35, which was well within the upper detection limit of 39 to 40 under the reaction conditions set for the assays. The CT standard curve corresponding to the matrix RNA derived from the RRT-PCR revealed a high correlation coefficient of 0.997 in the absence and between 0.971 and 0.989 in the presence of 0.5 to 2 fg/reaction of the IPC over a range of 9 log10 dilutions of the template RNA (not shown), indicating no apparent interference of the IPC with the detection of matrix RNA.

TABLE 2.

MDL of in vitro-transcribed matrix RNA by multiplex RRT-PCR in the presence of various amounts of IPCa

| AIV matrix RNA (copies/assay) | Average CT in the presence of IPC at (fg/reaction):

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 16 | 32 | 64 | |

| 2 × 106 | 26.68 | 26.44 | 26.75 | 27.80 | 27.78 | 28.10 | 28.80 | 29.12 | 29.56 |

| 2 × 105 | 29.91 | 29.21 | 29.84 | 30.94 | 31.30 | 31.11 | 31.85 | 32.24 | 32.82 |

| 2 × 104 | 32.26 | 31.71 | 32.44 | 33.00 | 33.55 | 34.04 | 34.34 | 34.88 | Negative |

| 2 × 103 | 34.53 | 34.89 | 35.86 | 37.12 | 37.44 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| 2 × 102 | 37.59 | 37.47 | 37.87 | >38.0b | >38.0 | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

The copy number of the AIV matrix RNA was estimated as previously reported (33). The CTs shown in the table are the averages of two reactions. The CTs corresponding to AIV matrix RNA at concentrations above 2 × 106 per reaction were minimally affected by the IPC at the above concentrations.

The CTs corresponding to 200 copies of AIV matrix RNA in the presence of IPC at 2 to 4 fg/reaction varied from negative to 38.

TABLE 4.

Multiplex RRT-PCR of serially diluted AIV RNA with armored RNA

| AIV RNA dilutiona |

CT

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| AI RNA only (FAM) | AIV RNA plus armored RNA

|

||

| FAM (AIV) | Texas Red (armored RNA) | ||

| Stock | 15.02 | 14.87 | Negative |

| 10−1 | 18.32 | 18.44 | Negative |

| 10−2 | 21.64 | 21.93 | Negative |

| 10−3 | 24.85 | 25.14 | Negative |

| 10−4 | 28.08 | 29.03 | Negative |

| 10−5 | 31.18 | 32.62 | 36.71 |

| 10−6 | 35.00 | 35.65 | 35.89 |

| 10−7 | 38.36 | 38.23 | 34.21 |

| 10−8 | Negative | Negative | 34.13 |

| 10−9 | Negative | Negative | 34.66 |

| Water | Negative | Negative | 34.43 |

Aliquots (140 μl) of serially diluted (10−1 to 10−9) AI virus Duck/Alberta/286/78 (H4N8), along with a fixed amount of armored RNA (33,250 copies), were extracted with Trizol. The extracted RNA was dissolved in 60 μl water, and 8 μl was used per reaction.

Detection of AIV RNA by multiplex RRT-PCR with lyophilized beads containing the IPC.

The LyB RRT-PCR master mixture containing AIV matrix primers, AIV matrix probe, MgCl2, IPC, and the IPC probe was lyophilized without the enzymes (Cepheid Corp., Sunnyvale, CA) because of concern for enzyme stability. The dNTPs were also excluded in the master mixture, as they interfered with the lyophilization process. The amount of IPC in the master mixture was carefully determined based on the results of multiplex RRT-PCRs with AIV matrix RNA and IPC (Table 2). Several multiplex RRT-PCRs were run with serially diluted AIV RNA (100 to 10−9) from several subtypes (H5, H2, and H11) in the absence and in the presence of the IPC at concentrations of 2.0 fg, 1.5 fg, 1.2 fg, 0.6 fg, 0.3 fg, and 0.15 fg per reaction (25 μl). In the absence or at higher dilutions of AIV RNA (10−7 to 10−9), the IPC was detectable at CTs between 33 and 38 when used at a concentration of 2.0, 1.5, or 1.2 fg per reaction (not shown). At 1.2 fg per reaction, the IPC had negligible effect on the detection of AIV RNA at any dilution, while at concentrations above 1.2 fg per reaction, it occasionally interfered with the detection of AIV RNA at higher dilutions (10−7 to 10−9), resulting in either higher CTs or no detection of target template (negative on the FAM channel), which could be due to the IPC outcompeting the AIV RNA. Therefore, 1.2 fg of the IPC per reaction (25 μl) was used for multiplex RRT-PCR. The IPC at that level had negligible effects on the detection of the viral RNA at any dilution (Table 3). The CT standard curve for the AIV RNA derived from the multiplex RRT-PCR revealed a high correlation coefficient of 0.997, representing nearly a linear dose-response curve over a range of 5 log10 units of input viral RNA (not shown). A direct correlation was found between the detection of the template (IPC or viral RNA) by RT-PCR and that by RRT-PCR; the amplification of the target amplicon (IPC or viral RNA) by RT-PCR determined by agarose electrophoresis coincided well with the detection of the amplicons determined by CTs from RRT-PCR assays (not shown). Therefore, 1.2 fg of the IPC per reaction (25 μl) was used for the lyophilized LyB RRT-PCR master mixture (beads). The compositions of all other ingredients in the beads remained the same as that described in Materials and Methods. Since potential loss of activity due to instability of the primers, probes, and IPC RNA at room temperature could have been an issue, the beads were always kept refrigerated (4 to 10°C). Under these storage conditions, the beads were stable for at least 6 months (the CTs corresponding to the IPC remained unchanged or dropped by less than one cycle). Beads were used in all subsequent experiments except those involving armored RNA.

TABLE 3.

Multiplex RRT-PCR of serially diluted AIV RNA with fixed IPC

| AIV RNA dilutiona |

CT

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| AIV RNA only (FAM) | AIV RNA plus IPC

|

||

| FAM (AIV) | Texas Red (IPC) | ||

| 10−1 | 17.92 | 17.39 | Negative |

| 10−2 | 21.34 | 20.45 | Negative |

| 10−3 | 24.51 | 23.89 | Negative |

| 10−4 | 27.83 | 27.33 | Negative |

| 10−5 | 31.41 | 30.91 | 38.93 |

| 10−6 | 35.07 | 33.76 | 34.74 |

| 10−7 | 38.86 | 37.59 | 35.21 |

| 10−8 | Negative | Negative | 35.32 |

| 10−9 | Negative | Negative | 35.25 |

| Water | Negative | Negative | 35.22 |

RNA extracted (Trizol LS) from A/chicken/NJ/15906-9/96 (H11N1) was serially diluted with RNase-free water; 8 μl of RNA from each dilution, along with 1.2 fg of the IPC per reaction, was subjected to RRT-PCR.

Detection of AIV RNA by multiplex RRT-PCR with armored RNA.

The armored RNA was used to monitor the accuracy of the viral-RNA extraction and subsequent analysis of the RNA by RT-PCR or RRT-PCR. Like the IPC, the armored RNA at the MDL was outcompeted by viral RNA in multiplex RRT-PCR. To determine the most effective concentration to be used as an extraction control, the armored RNA was added to serially diluted AIV at concentrations little higher than the MDL. The RNA was extracted by Trizol and subjected to multiplex RRT-PCR with LyB master mixture. Based on the results (not shown), we found 7 μl of armored RNA from a 10−7 dilution of the working stock (4.75 × 109 copies per μl), or 33,250 copies of RNA, was most effective to monitor the extraction of viral RNA by Trizol. Since the RNA extracted by Trizol was dissolved in 60 μl of water, 8 μl of which was used per reaction, the actual number of copies of armored RNA was estimated to be 4,433 per reaction (25 μl), which corresponded to an average CT of 34.6 (Table 4). When used at the above-mentioned dilution, the armored RNA had negligible effect on the detection of AIV RNA. If RRT-PCR inhibitors are present in the clinical sample, they can be detected by armored RNA if the latter is added to the samples and extracted with the AIV RNA.

Sensitivity and specificity of detection of AIV RNA with the beads.

To determine the sensitivities and specificities of detection of different AIV subtypes, RNAs from each of the 15 subtypes of AIV (H1 through H15) were serially diluted from 10−1 to 10−6 and then subjected to RRT-PCR with the lyophilized beads and the QIAGEN (5×) wet master mixture. The CT differences corresponding to each dilution (total, six dilutions) between the beads and the QIAGEN wet mixture were determined and then averaged. The results (Table 5) showed higher sensitivity for detection of AIV by RRT-PCR with beads than with the wet reagents (QIAGEN 5× master mixture) for most of the subtypes. The average CTs were 0.7624 cycles higher with wet reagents than with the beads (Table 5). To further validate the authenticity of the results, RNAs from 22 additional isolates of AIV of the subtypes H5, H3, H4, and H12 (all showing higher sensitivities of detection with the beads) were tested. The average CTs corresponding to 19 different isolates of the subtype H5 were found to be 2.88 cycles higher with wet reagents than with the beads (not shown), which correlates well with the results shown in Table 5. In additional experiments, the average CTs corresponding to six serial dilutions of AIV RNA (10−1 to 10−6) from Environment/NY/1909-6/98 (H3N8), Duck/Czech/56 (H4N6), and Duck/ALB/60/76 (H12N5) were found to be 0.252, 1.13, and 1.29 cycles higher, respectively (not shown), with the wet reagents versus the beads, indicating some variation but overall agreement of test results with those in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of the sensitivities of detection of AIV subtypes by RRT-PCR with wet and beads reagents

| AIV subtype | Description | Avg CT differencea (CTwet − CTbeads) |

|---|---|---|

| H1N1 | TK/SD/7034/86 | +0.465 |

| H2N9 | Gull/MD/19/77 | +0.493 |

| H3N6 | Gull/MD/704/77 | +1.858 |

| H4N5 | DK/ALB/286/78 | +0.980 |

| H5N2 | A/UNK/NY/118547-11/01 | +1.676 |

| H6N2 | CK/NY/14677-13/98 | +0.721 |

| H7N3 | CK/NSW/1688/97 | +0.584 |

| H8N4 | TK/ONT/6118/67 | +0.610 |

| H9N2 | CK/NJ/12220/97 | +0.720 |

| H10N | TK/VA/31049/91 | +0.796 |

| H11N1 | A/CK/NJ/15906-9/96 | +0.805 |

| H12N8 | DK/VIC/9211-18 | +1.243 |

| H13N6 | Gull/MD/704/77 | −0.101 |

| H14N5 | MA/GURJEV/263/82 | +0.676 |

| H15N6 | SHRWTR/W.AUST/2576/79 | −0.090 |

RNAs from all AIV subtypes (extracted by Trizol) were serially diluted from 10−1 to 10−6, and 8 μl from each dilution was subjected to RRT-PCR in duplicate with Qiagen wet (master) mixture and AIV matrix beads as described in te Materials and methods. The average CT corresponding to each dilution (total, six dilutions) of a given subtype determined with the AIV matrix beads was subtracted from that determined with the Qiagen wet mix (CTwet − CTbeads), the differences were averaged for all six dilutions, and the results are shown in the table. The overall average was +0.7624 ± 0.535 (standard deviation).

Accuracy and sensitivity of RRT-PCR diagnostics with beads on samples from experimentally infected chickens.

In this study, samples from chickens inoculated with AIV were subjected to AIV diagnostics by RRT-PCR with beads and wet reagents and by VI. A total of 66 tracheal swabs, 39 oropharyngeal swabs, and 16 cloacal swabs of chickens from three separate bird experiments were tested. The RNA was extracted from the swabs with Trizol LS. The birds were inoculated with A/chicken/TX/298313/04 (H5N2) (experiment 1), Chicken/NJ/150383/02 (H7N2) (experiment 2), and Chicken/Queretaro/14588-19/95 (H5N2) (experiment 3). The results of virus isolation of the samples from experiments 1 and 2 were reported elsewhere (22, 23). In experiment 1, out of the 32 tracheal swabs tested, 17 were positive and 15 were negative for AIV by virus isolation, which matched 100% with the RRT-PCR results (Table 6), and out of 16 cloacal swabs from this experiment, 8 were positive and 8 were negative for AIV by VI, while 9 were positive and 7 were negative for AIV by RRT-PCR, which gives 87% agreement of the test results between the two assays. In experiment 2, out of 34 tracheal swabs tested, 22 were positive and 12 were negative for AIV by VI, while 23 were positive and 11 were negative by RRT-PCR, which gives 94% agreement of the test results between the two assays. Both experiments show close agreement of test results between RRT-PCR and VI, indicating high accuracy of the RRT-PCR assays for the detection of AIV in clinical samples from chickens. The accuracy and sensitivity of detection of AIV by RRT-PCR with the beads were compared with those of QIAGEN wet reagents for all the clinical samples tested, including 30 oropharyngeal swabs from experiment 3. There was 100% agreement of test results between RRT-PCR assays with the beads and the wet reagents. The average CTs corresponding to AIV RNA for the positive samples from 17 tracheal swabs (experiment 1), 23 tracheal swabs (experiment 2), and 20 oropharyngeal swabs (experiment 3) were 2.18 (± standard deviation [SD]), 0.45 (±SD), and 2.42 (±SD) cycles higher, respectively, with QIAGEN wet reagents than with the beads (Table 6), indicating higher sensitivity of detection of AIV with the beads than with the wet reagents.

TABLE 6.

Comparison of the RRT-PCR assay with VI for clinical samples from experimentally infected birds

| Expta | Sample type | No. of samples | RRT-PCR resultsb

|

Avg CT difference (CTwet − CTbeads)c | VI resultsd

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | + | − | ||||

| 1 | Trachea | 32 | 17 | 15 | +2.18 ± 0.25 | 17 | 15 |

| Cloaca | 16 | 9 | 7 | NDe | 8 | 8 | |

| 2 | Trachea | 34 | 23 | 11 | +0.45 ± 0.14 | 22 | 12 |

| 3 | Oropharyngeal | 30 | 20 | 10 | +2.44 ± 0.82 | ND | ND |

Birds were inoculated with A/chicken/TX/298313/04 (H5N2) in experiment 1, with A/chicken/NJ/150383/02 (H7N2) in experiment 2, and with A/chicken/Queretaro/14588-19/95 (H5N2) in experiment 3. Samples were collected 3 days postinoculation in experiments 1 and 2, and 3, 6, and 8 days postinoculations in experiment 3. The RNA was extracted with Trizol LS.

RRT-PCR assays were carried out with lyophilized beads and Qiagen wet reagents as described in Materials and Methods. +, positive; −, negative.

CTs corresponding to the positive samples from each experiment were determined by RRT-PCR with lyophilized beads and Qiagen wet reagents as described in Materials and Methods. For each experiment, the CTs corresponding to AIV RNA of the samples determined with the beads were subtracted from those determined with Qiagen wet reagents, and the values were averaged.

ND, not determined.

Inhibition studies.

One of the most important applications of the IPC in RRT-PCR diagnostics of AIV is to detect PCR inhibitors in clinical samples. The presence of RT-PCR inhibitors was evaluated in blood, serum, kidney, lungs, spleen, intestine, chicken egg allantoic fluid, cloacal swabs, and oropharyngeal swabs. The results showed no inhibition of the amplification of viral RNA extracted from tracheal swabs, allantoic fluid, serum, and cloacal swabs of chickens from SEPRL flocks (Table 7). Neither the viral RNA nor the IPC was detectable in RNA extracted from cloacal swabs from wild birds or from tissues of the lungs, spleen, and intestine, indicating the presence of inhibitors in these samples. With RNA extracted from blood and kidney, the IPC was detectable at higher CTs, indicating partial inhibition of amplification of viral RNA. To test the levels of inhibitors in these samples, RNAs extracted from these samples were diluted 10, 100, and 1,000-fold and then tested by RRT-PCR. The inhibitors were diluted to noninhibitory levels in extracts of kidney and blood after a 10-fold dilution, in extracts of lungs after a 100-fold dilution, and in extracts of spleen and intestine after a 1,000-fold dilution. The inhibitor levels were high enough to block amplification of AIV RNA extracted from cloacal swabs of wild birds even after 1,000-fold dilution.

TABLE 7.

Detections of inhibitors in experimental samples

| Clinical samplea | Virus added |

CT

|

Interpretation (IPC)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAM (viral RNA) | Texas Red (IPC) | |||

| None (PBS) | Yes | 21.15 | Negative | Outcompete |

| Blood | ||||

| Undiluted | Yes | 31.57 | Negative | Partial inhibition |

| 10−1 dilution | 21.08 (20.13) | Negative | Outcompete | |

| Kidney | ||||

| Undiluted | Yes | 25.00 | Negative | Partial inhibition |

| 10−1 dilution | 21.81 (20.13) | Negative | Outcompete | |

| Lungs | ||||

| Undiluted | Yes | Negative | Negative | Inhibition |

| 10−2 dilution | 24.38 (24.11) | Negative | Outcompete | |

| Spleen | ||||

| Undiluted | Yes | Negative | Negative | Inhibition |

| 10−3 dilution | 27.58 (27.25) | Negative | Out compete | |

| Intestine | ||||

| Undiluted | Yes | Negative | Negative | Inhibition |

| 10−3 dilution | 25.67 (27.25) | Negative | Outcompete | |

| Serum | Yes | 21.19 | Negative | Outcompete |

| Tracheal swab | Yes | 21.28 | Negative | Outcompete |

| Cloacal swabsc | Yes | 21.16 | Negative | Outcompete |

| Cloacal swabsd | ||||

| Undiluted | Yes | Negative | Negative | Inhibition |

| 10−3 dilution | 38.53 | Negative | Partial inhibition | |

| Allantoic fluid | Yes | 19.88 | Negative | Outcompete |

| None (water) | No | Negative | 35.84 | |

All samples except cloacal swabs from wild birds were collected from specific pathogen-free chickens in SEPRL flocks. Two hundred microliters of samples from undiluted stocks (serum, allantoic fluid, and cloacal and tracheal swabs) or diluted stocks (10% [vol/vol] of blood or 10% [wet wt/vol] for kidney, spleen, lungs, or intestine in PBS), together with 50 μl of virus [GW/T/LA/169GW/68 (H10N7) (50% egg infective dose, 106/ml)] were extracted with Trizol LS. RNAs extracted from samples containing inhibitors were diluted as shown, and the CT values within parentheses represent those of the PBS control at the same dilutions.

Negative CT (IPC) on the Texas Red channel was interpreted as either inhibition or partial inhibition when the CT corresponding to viral RNA was negative or higher than that of the PBS control or as outcompeting when the CT corresponding to viral RNA was lower due to a higher concentration of the viral RNA.

From chickens of pathogen-free SEPRL flocks.

From wild birds, pooled from AIV-negative samples.

Comparison of lyophilized beads at a different laboratory.

The lyophilized beads were also tested in comparison with the wet reagents at the National Veterinary Services Laboratories in Ames, IA. In a comparison of 24 different H5 avian influenza virus isolates extracted with the RNeasy extraction kit, the wet reagents had a CT of 19.26 compared to a CT for the bead reagents of 16.30. The limit of detection using serially diluted samples showed a sensitivity similar to that with samples from both wet and bead reagents, detecting all of the diluted positive control samples up to a 10−6 dilution, detecting only a few at the 10−7 dilution and none at the higher dilutions. A variety of clinical samples, including tracheal swabs, cloacal swabs, and tissue samples, that were negative by VI were examined for evidence of PCR inhibition. Out of 32 samples tested, none had AIV matrix RNA amplified (FAM negative) by RRT-PCR with the beads, supporting the VI results; the IPC RNA was amplified in 20 samples but not in the remaining 12 samples, indicating the presence of RT-PCR inhibitors in the latter samples. Of the 12 samples that had evidence of inhibitors, 5 were from tissue samples, 5 were from cloacal swabs, and only 2 were from tracheal swabs.

DISCUSSION

Early detection of AIV in the course of the disease in poultry is an extremely important step toward the control, management, and eradication of avian influenza virus. RRT-PCR is a widely used molecular diagnostic test that can detect infection at its early stage. Although RRT-PCR is sensitive and specific for its target, concerns about false-negative reactions affecting test results have been raised. These false-negative reactions may be caused by the presence of RT-PCR inhibitors, poor viral-RNA extraction, user error in performing the RRT-PCR test, or poor quality of one of the reagents. In this report, we describe the use of an IPC and armored RNA to monitor the accuracy and specificity of the detection of AIV by RRT-PCR. The amounts of the IPC and the armored RNA used in multiplex RRT-PCR were adjusted so that that their presence did not interfere with the detection of the viral RNA at any dilution (Tables 3 and 4).

The IPC detected RT-PCR inhibitors in blood, cloacal swabs, and tissues from kidney, lungs, spleen, and intestine (Table 7). The presence of RT-PCR inhibitors in blood was also reported by others (2). RT-PCR inhibitors were detected in cloacal swabs (fecal samples) from wild birds but not in cloacal swabs of chickens collected from the SEPRL flocks. Since the fecal samples of wild birds vary depending on the habitat and diet of the birds, it is virtually impossible to determine the types of inhibitors present in such samples. Based on the RRT-PCR results (Table 7), it appears that the spleen and intestine carry more inhibitors than the lung, while the smallest amount of inhibitor(s) was found in the kidney and blood. Apparently, inhibitors were coextracted with the viral RNA by Trizol. Therefore, it is difficult to detect the virus in cloacal swabs from wild birds by RRT-PCR if the virus titer is low in the samples. Studies at the National Veterinary Services Laboratories have also shown that the sample type has an impact on the results, with tissue samples and cloacal swabs consistently having some evidence of PCR inhibition. When samples do have evidence of RT-PCR inhibition, diluting the RNA may eliminate the problem, but this will decrease the sensitivity of the test. Alternative procedures need to be considered to extract RNA without RT-PCR inhibitors. In some cases, virus isolation may be the best choice for the detection of AIV.

In this study, we developed and used lyophilized RRT-PCR master mixture reagents for the detection and analysis of AIV by RRT-PCR assays. The use of beads in RT-PCR and RRT-PCR diagnostics of Enterovirus and Adenovirus in clinical samples has recently been reported (4, 13, 28). Our results showed that lyophilized beads are generally more sensitive than the wet reagents (QIAGEN 5×) for the detection of both in vitro-transcribed AIV matrix RNA (Table 2) and AIV RNA extracted from experimentally infected birds (Tables 5 and 6). The higher sensitivity of detection with the beads is likely due to a combination of changes, including the change of buffer (LyB replacing QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR 5× buffer), use of a slightly larger amount of MgCl2 (4 mM for the lyophilized beads compared to 3.75 mM for the QIAGEN wet mixture), and a longer denaturation time (20 s for the beads compared to 1 s for the QIAGEN wet mixture) for the PCR cycle. Some of the advantages of the use of beads in RRT-PCR diagnostics are (i) reduced time to prepare the master mixture, since many of the reagents were premixed; (ii) the consistency and reproducibility of the assay, as the beads have a uniform composition; and (iii) minimizing of human errors, as the bead protocol reduces the number of manual steps. In addition, the inclusion of the IPC in the beads facilitates the detection of false-negative results in the samples.

In this report, we describe the use of AIV matrix beads for initial screening of the virus, and we have shown that it provides similar or improved results compared to the standardized test. The incremental improvements of the existing technology, with the proper validation, can improve the performance and ease of use of the test in the diagnostic laboratory.

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzanne DeBlois and Chang-Won Lee for their help in this project. We also thank Roger Schaller, David Yip, and Seema Patel from Cepheid for their support in the development of lyophilized beads.

This work was supported by USDA/ARS CRIS project number 6612-32000-039-00D and Homeland Security Funds 646-6612-480.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdulmawjood, A., S. Roth, and M. Bulte. 2002. Two methods for construction of internal amplification controls for the detection of Escherichia coli O157 by polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Cell Probes. 16:335-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akane, A., K. Matsubara, H. Nakamura, S. Takahashi, and K. Kimura. 1994. Identification of the heme compound co-purified with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from bloodstains, a major inhibitor of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. J. Forensic Sci. 39:362-372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander, D. J. 1982. Ecological aspects of influenza A viruses in animals and their relationship to human influenza: a review. J. R. Soc. Med. 75:799-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnot, T. J., and E. M. Swierkpsz. 2005. Evaluation of Cepheid's analyte-specific, real time PCR reagents for HSV (typing and non-typing), Enterovirus for diagnosis of CNS infections, poster S13. 21st Annu. Clin. Virol. Symp., Clearwater Beach, Fla., 8 to 11 May 2005.

- 5.Burnett, W. V. 1997. Northern blotting of RNA denatured by glyoxal without buffer re-circulation. BioTechniques 22:668-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castelain, S., V. Descamps, V. Thibault, C. Francois, D. Bonte, V. Morel, J. Izopet, D. Capron, P. Zawadzki, and G. Duverlie. 2004. TaqMan amplification system with an internal positive control for HCV RNA quantitation. J. Clin. Virol. 31:227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins, M. L., B. Irvine, D. Tyner, E. Fine, C. Zayati, C. Chang, T. Horn, D. Ahle, J. Detmer, L. P. Shen, J. Kolberg, S. Bushnell, M. S. Urdea, and D. D. Ho. 1997. A branched DNA signal amplification assay for quantification of nucleic acid targets below 100 molecules/ml. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2979-2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins, R. A., L. S. Ko, K. L. So, T. Ellis, L. T. Lau, and A. C. Yu. 2002. Detection of highly pathogenic and low pathogenic avian influenza subtype H5 (Eurasian lineage) using NASBA. J. Virol. Metods 103:213-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cubero, J., J. van der Wolf, J. van Beckhoven, and M. M. Lopez. 2002. An internal control for the diagnosis of crown gall by PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 51:387-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dingle, K. E., D. Crook, and K. Jeffery. 2004. Stable and noncompetitive RNA internal control for routine clinical diagnostic reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1003-1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domiati-Saad, R., and R. H. Scheuermann. 2005. Nucleic acid testing for viral burden and viral genotyping. Clin. Chim Acta 363:197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drosten, C., E. Seifried, and W. K. Roth. 2001. TaqMan 5′-nuclease human immunodeficiency virus type 1 PCR assay with phage-packaged competitive internal control for high-throughput blood donor screening. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4302-4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Echavarría, M., N. Basilotta, and G. Carballal. 2005. A generic multiplex real time PCR for detection of human adenoviruses: validation with various adenovirus serotypes, poster no. TA51. 21st Annu. Clin. Virol. Symp., Clearwater Beach, Fla., 8 to 11 May 2005.

- 14.Eisler, D. L., A. McNabb, D. R. Jorgensen, and J. L. Isaac-Renton. 2004. Use of an internal positive control in a multiplex reverse transcription-PCR to detect West Nile virus RNA in mosquito pools. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:841-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Favis, R., N. P. Gerry, Y. W. Cheng, and F. Barany. 2005. Applications of the universal DNA microarray in molecular medicine. Methods Mol. Med. 114:25-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fouchier, R. A., V. Munster, A. Wallensten, T. M. Bestebroer, S. Herfst, D. Smith, G. F. Rimmelzwaan, B. Olsen, and A. D. Osterhaus. 2005. Characterization of a novel influenza A virus hemagglutinin subtype (H16) obtained from black-headed gulls. J. Virol. 79:2814-2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia, M., D. L. Suarez, J. M. Crawford, J. W. Latimer, R. D. Slemons, D. E. Swayne, and M. L. Perdue. 1997. Evolution of H5 subtype avian influenza A viruses in North America. Virus Res. 51:115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan, G., H. O. Kangro, P. J. Coates, and R. B. Heath. 1991. Inhibitory effects of urine on the polymerase chain reaction for cytomegalovirus DNA. J. Clin. Pathol. 44:360-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleiboeker, S. B. 2003. Application of competitor RNA in diagnostic reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2055-2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lantz, P.-G., M. Matsson, T. Wadström, and P. Rådström. 1997. Removal of PCR inhibitors from human fecal samples through the use of an aqueous two-phase system for sample preparation prior to PCR. J. Microbiol. Methods 28:159-167. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasley, F. A. 1987. Economics of avian influenza: control vs non-control, p. 390-399. In C. W. Beard and B. C. Easterday (ed.), Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Avian Influenza. U.S. Animal Health Association, Richmond, Va.

- 22.Lee, C. W., Y. J. Lee, D. A. Senne, and D. L. Suarez. 7July2006. Pathogenic potential of North American H7N2 avian influenza virus: a mutagenesis study using reverse genetics. Virology. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lee, C. W., D. E. Swayne, J. A. Linares, D. A. Senne, and D. L. Suarez. 2005. H5N2 avian influenza outbreak in Texas in 2004: the first highly pathogenic strain in the United States in 20 years? J. Virol. 79:11412-11421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monteiro, L., D. Bonnemaison, A. Vekris, K. G. Petry, J. Bonnet, R. Vidal, J. Cabrita, and F. Megraud. 1997. Complex polysaccharides as PCR inhibitors in feces: Helicobacter pylori model. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:995-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy, B. R., and R. G. Webster. 1996. Orthomyxoviruses, p. 1397-1445. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed., vol. 1. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer, S., A. P. Wiegand, F. Maldarelli, H. Bazmi, J. M. Mican, M. Polis, R. L. Dewar, A. Planta, S. Liu, J. A. Metcalf, J. W. Mellors, and J. M. Coffin. 2003. New real-time reverse transcriptase-initiated PCR assay with single-copy sensitivity for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in plasma. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4531-4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasloske, B. L., C. R. Walkerpeach, R. D. Obermoeller, M. Winkler, and D. B. DuBois. 1998. Armored RNA technology for production of ribonuclease-resistant viral RNA controls and standards. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3590-3594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raggam, R. B., E. Leitner, J. Berg, G. Muhlbauer, E. Marth, and H. H. Kessler. 2005. Single-run, parallel detection of DNA from three pneumonia-producing bacteria by real-time polymerase chain reaction. J. Mol. Diagn. 7:133-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salamone, S., A. J. Brown, and K. A. Stellrecht. 2005. Comparison of the Cepheid Enterovirus Primer and Probe Set, the bioMerieux Enterovirus Real-Time NASBA ASR, and an in-house developed enterovirus RT-PCR assay, poster S9. 21st Annu. Clin. Virol. Symp., Clearwater Beach, Fla., 8 to 11 May 2005.

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Schwaiger, M., and P. Cassinotti. 2003. Development of a quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay with internal control for the laboratory detection of tick borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) RNA. J. Clin. Virol. 27:136-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shortridge, K. F., P. Gao, Y. Guan, T. Ito, Y. Kawaoka, D. Markwell, A. Takada, and R. G. Webster. 2000. Interspecies transmission of influenza viruses: H5N1 virus and a Hong Kong SAR perspective. Vet. Microbiol. 74:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spackman, E., D. A. Senne, T. J. Myers, L. L. Bulaga, L. P. Garber, M. L. Perdue, K. Lohman, L. T. Daum, and D. L. Suarez. 2002. Development of a real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for type A influenza virus and the avian H5 and H7 hemagglutinin subtypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3256-3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suarez, D. L. 2000. Evolution of avian influenza viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 74:15-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suarez, D. L., M. Garcia, J. Latimer, D. Senne, and M. Perdue. 1999. Phylogenetic analysis of H7 avian influenza viruses isolated from the live bird markets of the Northeast United States. J. Virol. 73:3567-3573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swayne, D. E., and D. L. Suarez. 2000. Highly pathogenic avian influenza. Rev. Sci. Technol. 19:463-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner, P. D., P. Maruvada, and S. Srivastava. 2004. Molecular diagnostics: a new frontier in cancer prevention. Exp. Rev. Mol. Diagn. 4:503-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webster, R. G., W. J. Bean, O. T. Gorman, T. M. Chambers, and Y. Kawaoka. 1992. Evolution and ecology of influenza viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 56:152-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson, I. G. 1997. Inhibition and facilitation of nucleic acid amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3741-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong, M. L., and J. F. Medrano. 2005. Real-time PCR for mRNA quantitation. BioTechniques 39:75-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuen, K. Y., P. K. Chan, M. Peiris, D. N. Tsang, T. L. Que, K. F. Shortridge, P. T. Cheung, W. K. To, E. T. Ho, R. Sung, and A. F. Cheng. 1998. Clinical features and rapid viral diagnosis of human disease associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. Lancet 351:467-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]