Abstract

In spite of the decrease in the number of registered leprosy patients, the number of new cases diagnosed each year (400,000) has remained essentially unchanged. Leprosy diagnosis is difficult due to the low sensitivity of current methodologies to identify new cases. In this study, conventional and TaqMan real-time PCR assays for detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA were compared to current classification based on clinical, bacteriological, and histological evaluation. M. leprae DNA was extracted from frozen skin biopsy specimens from 69 leprosy patients enrolled in the study and was amplified using specific primers for either the antigen 85B-coding gene or the 85A-C intergenic region by using conventional and real-time PCR. The detection rate was 100% among multibacillary (MB) patients and ranged from 62.5% to 79.2% among paucibacillary (PB) patients according to the assay used. The TaqMan system for 85B gene amplification showed the highest sensitivity, although conventional PCR using the 85A-C gene as a target was also efficient. The cycle threshold (CT) values obtained using the TaqMan system were able to statistically (P < 0.0001) differentiate MB (mean CT, 28.06; standard deviation [SD], 4.51) from PB (mean CT, 33.06; SD, 2.24) patients. Also, there was a correlation between CT values and the bacteriological index for MB patients (Pearson's r, −0.444; P = 0.008). Within the PB patients' group, we tested normal skin from six patients exhibiting the pure neuritic form of leprosy (PNL). Five out of six PNL patients were positive for the presence of M. leprae DNA, even in the absence of skin lesions. In conclusion, the TaqMan real-time PCR developed here seems to be a useful tool for rapidly detecting and quantifying M. leprae DNA in clinical specimens in which bacilli were undetectable by conventional histological staining.

Leprosy, a chronic inflammatory disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae, an obligately intracellular pathogen, has existed throughout recorded history. According to the clinical spectrum proposed by Ridley and Jopling (15), leprosy is characterized by two polar forms, a paucibacillary tuberculoid and a multibacillary lepromatous (LL) form, and by three intermediate forms, the borderline tuberculoid (BT), borderline borderline (BB), and borderline lepromatous (BL) forms. Patients can also exhibit a rare form known as pure neural leprosy (PNL), which is an isolated clinical entity characterized mainly by the uniqueness of nerve lesions. Also, PNL is difficult to diagnose, because skin lesions and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in slit smears are absent.

Most people within populations where leprosy is endemic have been exposed to M. leprae, but few develop the disease, suggesting that a minority are susceptible to leprosy (11) while the majority of the population present some sort of genetic resistance (5). Although recent advances have been achieved in the definition of genetic markers for host susceptibility, the diagnosis of leprosy is still very difficult, due in part to the inability to grow M. leprae in vitro. The diagnosis of leprosy is based on microscopic detection of AFB in tissue smears, in combination with histopathological and clinical evaluation. Acid-fast staining requires at least 104 organisms per g of tissue for reliable detection (21), though its sensitivity is low, especially for patients at the tuberculoid end of the leprosy spectrum, where AFB are rare or absent.

Serological tests for leprosy diagnosis (3) have shown a certain potential for detection and identification of the host immune response against the mycobacteria. Even so, detection of bacteria is difficult, and histological findings can be nonspecific. Therefore, simple and specific PCR systems for detection of small numbers of bacteria in clinical samples have been proposed. Different target sequences for PCR, such as genes encoding the 36-kDa antigen (7), the 18-kDa antigen (20), or the 65-kDa antigen (14) and the repetitive sequences (8) of M. leprae, are available. Recently, real-time PCR technology has improved the diagnosis of many pathogens (9, 17). One of the advantages of this method is the quantitation of bacterial DNA content in clinical samples. Nevertheless, real-time detection of M. leprae did not increase the clinical sensitivity of PCR over that of conventional protocols (10).

In countries with high prevalences of leprosy, diagnosis will continue to rely on clinical and microscopic examination. However, molecular assays can be very useful to clarify unclear and suspected cases. Diagnosis of PNL, for example, can be conclusive after detection through PCR of M. leprae DNA from nerve biopsy specimens (6). Also, reverse transcription-PCR can be used as a measure of M. leprae viability and consequently can assess the efficacy of multidrug therapy (4).

In this study we present a comparison of different PCR detection methods for the M. leprae gene encoding antigen 85B and for the 85A-C intergenic region, amplified from DNA extracted from frozen skin biopsy specimens. The antigen 85 complex consists of three structurally related components (A, B, and C) encoded by three genes (fbpA, fbpB, and fbpC, respectively) located at separate loci, although fbpA (ML 0097) and fbpC (ML 0098) are clustered in the mycobacterial genome (16). Thus, conventional PCR was compared with a versatile detection platform for real-time PCR (TaqMan), and the efficiency of each method was determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection and processing of clinical material.

Punch skin biopsy (6-mm3) samples from patients were obtained at the outpatient unit of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute, Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The patients were classified clinically, bacteriologically, and histopathologically, according to the Ridley-Jopling scale (15). A total of 69 frozen skin biopsy samples were obtained from patients with all different clinical forms: 25 samples from LL, 11 from BL, 3 from BB, and 24 from BT patients, and 6 samples from healthy areas of PNL patients, who were diagnosed as described by Jardim and coworkers (6). Multibacillary (MB) patients (comprising BB, BL, and LL patients) had bacteriological indexes (BI) ranging from +0.33 to +5.5 (mean, 4.07), while all paucibacillary (PB) patients (including BT and PNL patients) had negative BI. Five skin biopsy specimens from healthy individuals with no previous contact with leprosy patients were also analyzed. Before the study was undertaken, the patients and healthy individuals were informed of the purpose of the study, and written consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the FIOCRUZ Ethical Committee.

DNA extraction from skin biopsy specimens.

DNA was extracted from 6-mm3 skin biopsy specimens using proteinase K digestion as described elsewhere (24) with modifications. The 6-mm3 skin biopsy specimens were cleaved in half, and one piece was thawed at room temperature, minced, and lysed by three cycles of freezing (in an ethanol-dry-ice bath) and thawing (at 95°C). Samples were digested for 12 h at 60°C with proteinase K (300 μl/ml) in 100 mmol/liter Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/liter NaCl, and 10 mmol/liter EDTA (pH 8.0). Proteinase K was heat inactivated at 95°C for 10 min, and homogenates were extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol. DNA was precipitated with isopropanol, washed in 70% ethanol, dried at room temperature, and resuspended in 8 mM NaOH.

Nucleic acid extraction using Trizol.

The method using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, NJ) enables the extraction of DNA, RNA, and protein from the same samples and was employed for anesthetic skin samples from PNL patients. A 6-mm3 biopsy sample was homogenized in 2 ml of Trizol reagent in a Polytron PT 3000 probe for tissue disruption. Following RNA extraction, DNA was purified according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, DNA was precipitated with ethanol from the remaining interphase and organic phase. The phenol-ethanol phase was removed, and the DNA pellet was washed twice in a solution containing 0.1 M sodium citrate in 10% ethanol. DNA was dissolved in 8 mM NaOH.

Conventional PCR.

Each specimen was amplified by PCR using a pair of primers to produce a 250-bp fragment of the M. leprae 85A-C intergenic region (sense, 5′-ATA CTG TTC ACG CAG CAT CG-3′; antisense, 5′-GTT GAA GGC ATC AAG CAG GT-3′). The 85A-C product comprises the region between the fbpA and fbpC genes. Another primer pair, which amplified a 263-bp fragment of the 85B antigen-coding region of M. leprae (sense, 5′-CAA TAG GAG TGT CAA ATC C-3′; antisense, 5′-TTC CCA GCC TGC AGA ATG-3′), was also tested. Two microliters of the processed clinical sample (generally 50 to 200 ng) was added to 25 μl of reaction mixture, comprising 1× buffer (Invitrogen), 1 U Taq DNA polymerase, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 0.5 μM each primer). Initial incubation for 5 min at 94°C was followed by 35 cycles of 45 s at 94°C, 45 s at 60°C, and 90 s at 72°C and a final extension cycle of 7 min at 72°C. The results were ascertained according to the presence or absence of specific bands visualized after agarose gel electrophoresis (1.7%), ethidium bromide staining, and UV transillumination. Each sample was tested twice, and the readout could be given (98% agreement between the tests). When results for the same system were different, a third PCR with that sample was performed for confirmation. The result of this PCR defines whether the sample is positive or negative for M. leprae DNA. PCR results were checked independently by two different researchers, and the results were always confirmatory.

A standard curve of DNA was composed by serial dilution of purified M. leprae DNA from an infected armadillo; amounts ranged from 1 ng to 100 ag. For specificity experiments, DNA from other mycobacterial species (kindly provided by Phillip Suffys) was also tested by conventional and real-time PCRs.

Real-time PCR using TaqMan.

A 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled TaqMan probe (5′-CTC GGC CCT AAT ACT GG-3′) and a primer set (sense, 5′-GTG GTC GGC CTC TCG AT-3′; antisense, 5′-CGA GCC AGC ATA GAT GAA CTG ATC-3′) (Applied Biosystems) were designed to amplify an 80-bp fragment of the 85B gene. Two microliters of the processed clinical sample (generally 50 to 200 ng) were used in a total PCR volume of 10 μl. Reagents utilized included the TaqMan 2× master mix containing 1× TaqMan buffer, 5 mM MgCl2, 400 μM dUTP, 200 μM (each) dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, 8% glycerol, AmpliTaq Gold (0.025 U/μl), AmpErase UNG (0.01 U/μl), 300 nM each forward and reverse primer, and 100 nM probe. The kit was utilized according to the manufacturer's directions, and reaction mixtures were subjected to 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The TaqMan probe labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein was cleaved during amplification, generating a fluorescent signal. Unknown values were interpolated automatically from the DNA standard curve. The results were ascertained according to the cycle of amplification that yielded a detectable fluorescence signal for the first time (cycle threshold [CT]); results lower than 39 (the cutoff) were considered positive. For this system, two DNA standard curves, composed of serial dilutions of purified M. leprae DNA from an infected armadillo ranging from 1 ng to 100 ag (10-fold dilution) and from 100 fg to 6.25 fg (2-fold dilution), were merged.

Statistical analysis.

The standard curve using CT values versus serial DNA concentrations was calculated using a linear regression model. Differences between average MB and PB CT values were calculated using Student's t test. Pearson's r test was used to correlate BI with CT values for MB samples. All statistical calculations were done with GraphPad software, version 3.01.

RESULTS

Specificity and analytical sensitivity.

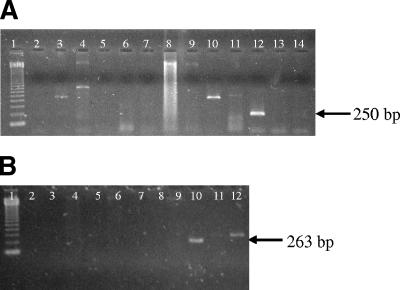

Specificity and sensitivity were tested for each of the three systems (conventional PCR of 85A-C [conventional 85A-C], conventional 85B, and TaqMan PCR of 85B [TaqMan 85B]). The specificity of conventional PCR was determined by including DNA from nine other mycobacterial species and human genomic DNA. For both systems, 85A-C and 85B, specific amplified products of 250 bp and 263 bp, respectively, were detected only for M. leprae DNA (Fig. 1A and B). To assess the specificity of the TaqMan system for DNA from M. leprae, nine other mycobacterial species and human genomic DNA were tested. None of the reactions yielded positive results (cutoff CT, ≤39) except for the reaction containing M. leprae DNA (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products (1.7%) demonstrating specificity for M. leprae. (A) Conventional 85A-C. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker (123 bp); 2, M. avium; 3, M. tuberculosis; 4, M. marinum; 5, M. intracellulare; 6, M. vaccae; 7, M. xenopi; 8, M. fortuitum; 9, M. flavescens; 10, M. bovis; 11, M. kansasii; 12, M. leprae; 13 and 14, human DNA. (B) Conventional 85B. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker (123 bp); 2, M. phlei; 3, M. intracelullare; 4, M. fortuitum; 5, M. avium; 6, M. tuberculosis; 7, M. vaccae; 8, M. kansasii; 9, M. bovis; 10, M. leprae; 11 and 12, human DNA.

TABLE 1.

Selectivity of TaqMan assay for the detection of M. leprae and related organismsa

| Species | CT |

|---|---|

| M. leprae | 26.6 ± 0.1 |

| M. kansasii | >40 |

| M. marinum | >40 |

| M. scrofulaceum | >40 |

| M. xenopi | >40 |

| M. smegmatis | >40 |

| M. gordonae | >40 |

| M. tuberculosis | >40 |

| M. avium | >40 |

| M. aurum | >40 |

| M. vaccae | 39.6 |

| Human DNA | >40 |

The reaction mixture contained 100 pg of template DNA. No signal for NTC was detected over 40 cycles.

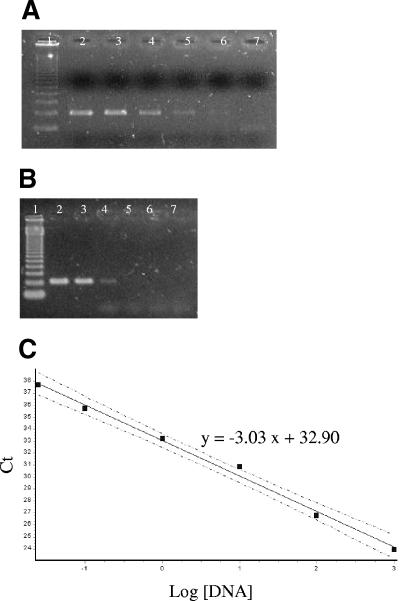

Analytical sensitivity was measured and the detection limit determined for each system by considering a standard curve from purified M. leprae DNA. The detection limits of the systems were compared (100 fg for conventional 85A-C, 10 pg for conventional 85B, and 25 fg for TaqMan 85B), yielding a CT of 37.53 ± 0.1 (Fig. 2A, B, and C). Also, determination of the analytical sensitivity of real-time PCR using SYBR Green I and the same primers for conventional PCR of 85A-C demonstrated that conventional PCR is 104 times more sensitive than the SYBR Green system (data not shown). The standard curve obtained for the TaqMan 85B system with a serially diluted M. leprae genomic DNA preparation was linear with a coefficient of correlation of 0.9964 and a slope of −3.03, corresponding to a PCR efficiency of >90% (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Detection limits of M. leprae DNA by the conventional 85A-C, conventional 85B, and TaqMan systems. (A and B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products (1.7%) demonstrating the sensitivity of the conventional 85A-C (A) or 85B (B) system. Lanes: 1, molecular weight marker (123 bp); 2, 1 ng; 3, 100 pg; 4, 10 pg; 5, 1 pg; 6, 100 fg; 7, 10 fg. (C) Linear range of quantitation of M. leprae DNA by the TaqMan assay. The log10 copy number of DNA input into each test reaction mixture prior to DNA preparation (x axis) is plotted against the CT. Standard deviations are for triplicate assays (dashed lines) where mean CTs and SDs are as follows: for 1 ng, 23.66 ± 0.22; for 100 pg, 26.52 ± 0.17; for 10 pg, 30.41 ± 0.12; for 1 pg, 33.12 ± 0.10; for 100 fg, 35.83 ± 0.10; for 25 fg, 37.53 ± 0.10.

Efficiency of PCR systems in clinical samples.

Since conventional PCR targeting antigen 85B had an analytical sensitivity 100 times lower than the conventional system targeting intergenic region 85A-C, the latter was chosen for further analysis. The results showed no differences between the detection rates from multibacillary patient samples for the detection systems used (Table 2). The detection rate was 100% for both systems.

TABLE 2.

Efficiencies of different PCR systems with skin biopsy specimens from MB, PB, and PNL patients

| Form of leprosy | No. of positive samples detected/total no. (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional PCR (85A-C) | TaqMan PCR (85B) | Any test | |

| MB (LL, BL, BB) | 39/39 (100) | 39/39 (100) | 39/39 (100) |

| PB (BT) | 15/24 (62.5) | 19/24 (79.2) | 20/24 (83.3) |

| PNL | 3/6 (50) | 5/6 (83.3) | 5/6 (83.3) |

| Total | 57/69 (82.6) | 63/69 (91.3) | |

Detection of M. leprae in samples from PB patients is difficult due to the low number of bacilli present (negative BI). Therefore, the molecular detection rate obtained from samples of PB patients was lower than that from MB patients and differed according to the system (Table 2). Data obtained from DNA samples showed better results for TaqMan 85B (79.2%) than for the conventional system targeting region 85A-C, which also presented a high detection rate of 62.5%. Only four PB samples were negative when results from both systems were combined. To control any possible PCR inhibition, conventional PCR targeting the human β-actin gene was performed. All samples were positive (data not shown). Also, the potential inhibitory effect of human genomic DNA was evaluated by spiking fixed amounts of M. leprae DNA with increasing concentrations of human genomic DNA; as much as 200 ng of human DNA per reaction mixture had no significant inhibitory effect on the amplification of a starting amount of 10 pg of M. leprae DNA. The addition of 200 ng or more of human genomic DNA resulted in an increasing inhibition up to 1,000 ng (data not shown).

To confirm the efficacy of the new methodology in detecting M. leprae DNA, we tested six individuals with pure neuritic leprosy and without apparent skin lesions. Biopsy specimens taken from a healthy area of the skin were tested. All six samples obtained in this study were extracted with Trizol reagent. In this group, five of six patients (83.3%) tested positive by the TaqMan 85B system and three of six (50%) tested positive by the conventional 85A-C system (Table 2).

Also, to test for false-positive (nonspecific) results, the variability of readouts in background samples was assessed for both systems. To accomplish that, five skin biopsy samples from healthy individuals were used for M. leprae detection by real-time and conventional PCR; as expected, none of these presented a positive result. Thus, after the analysis of the contingency table, clinical sensitivity and specificity could be assessed for both PCR systems. The TaqMan 85B PCR system presented a slightly higher sensitivity (91.3%; confidence interval, 82% to 96%; P = 0.0001) than the conventional system targeting region 85A-C (82.6%; confidence interval, 0.71 to 0.90; P = 0.0001). Similarly, clinical specificity was determined, and both systems presented 100% specificity.

For the 63 biopsy samples extracted with proteinase K, the overall agreement was 100% (39/39) for MB and 75% (18/24) for PB samples. Among these discordant samples, five of six were positive by TaqMan 85B but not by conventional 85A-C, while one sample was positive by conventional 85A-C only.

The TaqMan 85B system was also used to compare the CT values among multibacillary patients with those among paucibacillary patients (Fig. 3A). When the TaqMan assay was used, it was possible to demonstrate that the amounts of M. leprae DNA present in skin biopsy specimens differ according to patients' clinical spectra. The CT values for PB patients were higher, ranging from 29.18 to 37.65 (mean CT, 33.06; standard deviation [SD], 2.24). On the other hand, for MB patients, the values ranged from 22.05 to 36.71 (mean CT, 28.06; SD, 4.51). The comparison of M. leprae DNA levels in the two groups demonstrated an extremely significant difference (P < 0.0001). Also, the Pearson r test was used to correlate CT and BI values among MB samples, and a significant association was observed (r = −0.4447; P = 0.0084). As expected, higher CT values were correlated with lower BI values, and lower CT values were correlated with higher BI values (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Quantification of M. leprae DNA as a function of the clinical spectrum of the disease. (A) CT values among multibacillary versus paucibacillary patients (P < 0.0001). (B) Linear Pearson correlation between BI and CT values for MB patients (P = 0.0084; r = −0.4447).

DISCUSSION

In clinical practice, it would be useful to detect M. leprae DNA by PCR on regularly bacteriologically negative samples. The diagnosis of early-PB leprosy and PNL may be difficult, and PCR may enhance the ascertainment of new cases. We observed from our results that the positivity rates of PB samples extracted with proteinase K were similar for conventional 85A-C and TaqMan 85B, although the latter presented a higher detection rate. Furthermore, assessment of normal skin biopsy specimens from healthy individuals excluded the possibility of false-positive results, ensuring a specificity of 100% for both systems. Obviously, the control sample size was small, but for ethical reasons we chose not to enlarge the sampling. Overall positive rates (i.e., the clinical sensitivity of each system) were 91.3% and 82.6% for the TaqMan and conventional systems, respectively.

One explanation for negative results among PB patient samples might be their intrinsically higher ratios of human genomic DNA to M. leprae DNA, which probably inhibit M. leprae DNA amplification. Potential inhibition by human DNA in M. leprae PCR is an issue, but to ensure maximum efficiency in using this system, it is suggested that total DNA extracted from human samples be quantified and serially diluted prior to amplification of M. leprae DNA. In the present study, a higher positive detection rate for the PB pole from skin biopsy samples was observed than for previously described methods (7, 8, 10, 14, 19, 20, 24). Moreover, our technique does not require the hybridization step, and both the conventional and real-time PCRs described here showed increased clinical sensitivity for PB patients.

Based on the analytical data, it could be estimated that real-time PCR can detect around 5 M. leprae genomes (25 fg, equivalent to a CT of 37,65). Thus, the analytical sensitivity was lower than that for other studies, which detected a quantity equal to about 1/10 of the bacterial genome (19), even though, for the BT group, we were able to correctly identify 79.2% of patients with no detectable bacilli by using the bacteriological assessment. The sensitivity of the acid-fast staining technique has been evaluated, and it seems that 104 bacteria per g of tissue is the detection limit (15). Assuming that the biopsy piece used weighs 10 mg, 100 mycobacteria would be needed in order to unequivocally detect M. leprae in these biopsy specimens by the acid-fast technique. Combining these observations with our data, we could suggest that the real-time PCR method is at least 20 times more sensitive than the AFB staining technique with clinical samples. In fact, from the analysis of the dynamic range in clinical samples (CT, 29.1 to 37.65), we can predict that for BT patients, we have 5 genomes (CT, 37.65) to 4 × 103 genomes (CT, 29) per skin biopsy specimen analyzed. Thus, it was interesting that the number of genome copies presented by some PB patients according to the TaqMan system was as much as 40 times higher than the number of mycobacteria required for AFB staining. This suggests that the molecular analysis is far more sensitive and accurate than AFB staining and also indicates that microscopic examination of the lymph is unable to correctly identify MB patients. This finding has clinical implications, since it seems that a number of patients have been misdiagnosed and undertreated.

Real-time chemistry allows for the detection of PCR amplification during the early phases of the reaction, enabling the TaqMan real-time system to quantify the bacterial load. There was a clear difference between the levels of M. leprae DNA in multibacillary versus paucibacillary patients: the mean CT values indicate that MB patients have on average 5 log units more mycobacterial DNA. As expected, a positive result by microscopic examination of the lymph from MB patients was significantly correlated with a positive real-time PCR result. Therefore, higher BI were detected earlier, demonstrating lower CT values, i.e., higher concentrations of M. leprae DNA. Even though the correlation between CT and BI was not perfect, this could be explained by the different amounts of M. leprae DNA in the lymph and in the skin. Another possible explanation for the low r values is the lack of sensitivity of AFB testing. Thus, our molecular analyses are precisely corroborating the clinical data and could also be useful in determining a molecular bacteriological index, helping to define the clinical forms of patients' conditions.

An important issue to be considered is that in-house PCR reproducibility is low. In this work, gel eletrophoretic analysis of the products of conventional PCR of the 85A-C intergenic region was considered positive when a single specific fragment of 250 bp was visualized. Therefore, reagent quality, especially the quality of the PCR buffer and Taq DNA polymerase, must be considered in order to ensure maximum efficiency and amplification of a PCR product with a unique band.

Also, real-time PCR is becoming more widely used for diagnostic purposes due to its semiautomated format flexibility and speed, providing an obvious experimental advantage in routine lab work and an analytical sensitivity slightly but consistently higher (25 fg) than that of conventional PCR of 85A-C (100 fg). Moreover, clinical sensitivity was also higher for real-time than for conventional PCR systems. Nevertheless, no differences were found between the systems in a previous work comparing conventional and TaqMan real-time PCR amplification of a 530-bp proline-rich antigen gene in skin biopsy specimens from leprosy patients (10).

In this study, we tested M. leprae DNA extraction protocols for diagnostic purposes using a regularly established proteinase K method. Our results also suggest that using Trizol as the DNA extraction reagent, after a previous RNA extraction, recovers DNA of good quality. Thus, PCR could subsequently be used for rapid detection of M. leprae in skin from PNL patients. Additionally, RNA could be saved and used for other studies such as gene expression analysis, which is useful for research purposes. Likewise, amplification using TaqMan 85B seems to be a reasonable test for the diagnosis of PNL, where skin lesions are always absent, since five out of six skin samples from PNL patients were positive for M. leprae DNA. This result suggests an alternative way to envision leprosy diagnosis in cases where PNL is suspected but nerve biopsy samples are unavailable.

Several findings on leprosy indicate that M. leprae transmission occurs mainly by inhalation. Therefore, for purposes of clinical practice, the application of PCR for the detection of M. leprae DNA in samples from household contacts has been reported (1, 2, 13). Although PCR could be a useful tool for the detection of subclinical infections, none of these investigations have consistently associated the presence of M. leprae DNA with further development of the disease. However, association with a serological test could improve the predictive value of PCR in leprosy diagnosis (23, 25). In spite of the higher cost of real-time PCR than of routine bacteriological techniques, we reported the presence of M. leprae DNA in 79.2% of PB samples (TaqMan 85B), which is encouraging, at least, for future screening of high-risk individuals such as household contacts.

Another approach to understanding M. leprae transmission would be detection and genotyping of clinical isolates (12, 26). Microsatellite, minisatellite, and single-nucleotide polymorphism studies substantiate the polymorphic loci as promising candidates for molecular typing tools for leprosy epidemiology. Therefore, the results reported in this study, combined with genotyping data, could enhance our ability to target drug therapy campaigns and could lead to improved control strategies.

Our results suggest that TaqMan real-time PCR using components of the antigen 85 gene complex as targets, together with proteinase K DNA extraction, is a useful tool for the rapid detection of M. leprae in clinical specimens in which no AFB are detectable microscopically and should be employed in difficult-to-diagnose cases such as PNL.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida, E. C., A. N. Martinez, V. C. Maniero, A. M. Sales, N. C. Duppre, E. N. Sarno, A. R. Santos, and M. O. Moraes. 2004. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae DNA by polymerase chain reaction in the blood and nasal secretion of Brazilian household contacts. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 99:509-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyene, D., A. Aseffa, M. Harboe, D. Kidane, M. Macdonald, P. R. Klatser, G. A. Bjune, and W. C. Smith. 2003. Nasal carriage of Mycobacterium leprae DNA in healthy individuals in Lega Robi village, Ethiopia. Epidemiol. Infect. 131:841-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buhrer-Sekula, S., H. L. Smits, G. C. Gussenhoven, J. van Leeuwen, S. Amador, T. Fujiwara, P. R. Klatser, and L. Oskam. 2003. Simple and fast lateral flow test for classification of leprosy patients and identification of contacts with high risk of developing leprosy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1991-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chae, G. T., M. J. Kim, T. J. Kang, S. B. Lee, H. K. Shin, J. P. Kim, Y. H. Ko, S. H. Kim, and N. H. Kim. 2002. DNA-PCR and RT-PCR for the 18-kDa gene of Mycobacterium leprae to assess the efficacy of multi-drug therapy for leprosy. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:417-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feitosa, M. F., I. Borecki, H. Krieger, B. Beiguelman, and D. C. Rao. 1995. The genetic epidemiology of leprosy in a Brazilian population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 56:1179-1185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jardim, M. R., S. L. Antunes, A. R. Santos, O. J. Nascimento, J. A. Nery, A. M. Sales, X. Illarramendi, N. Duppre, L. Chimelli, E. P. Sampaio, and E. P. Sarno. 2003. Criteria for diagnosis of pure neural leprosy. J. Neurol. 250:806-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kampirapap, K., N. Singtham, P. R. Klatser, and S. Wiriyawipart. 1998. DNA amplification for detection of leprosy and assessment of efficacy of leprosy chemotherapy. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 66:16-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang, T. J., S. K. Kim, S. B. Lee, G. T. Chae, and J. P. Kim. 2003. Comparison of two different PCR amplification products (the 18-kDa protein gene vs. RLEP repetitive sequence) in the diagnosis of Mycobacterium leprae. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 28:420-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kesanopoulos, K., G. Tzanakaki, S. Levidiotou, C. Blackwell, and J. Kremastinou. 2005. Evaluation of touch-down real-time PCR based on SYBR Green I fluorescent dye for the detection of Neisseria meningitidis in clinical samples. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 43:419-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramme, S., G. Bretzel, M. Panning, J. Kawuma, and C. Drosten. 2004. Detection and quantification of Mycobacterium leprae in tissue samples by real-time PCR. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 193:189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mira, M. T., A. Alcais, V. T. Nguyen, M. O. Moraes, C. Di Flumeri, H. T. Vu, C. P. Mai, T. H. Nguyen, N. B. Nguyen, X. K. Pham, E. N. Sarno, A. Alter, A. Montpetit, M. O. Moraes, J. R. Moraes, C. Dore, C. J. Gallant, P. Lepage, A. Verner, E. Van De Vosse, T. J. Hudson, L. Abel, and E. Schurr. 2004. Susceptibility to leprosy is associated with PARK2 and PACRG. Nature 427:636-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monot, M., N. Honore, T. Garnier, R. Araoz, J. Y. Coppee, C. Lacroix, S. Sow, J. S. Spencer, R. W. Truman, D. L. Williams, R. Gelber, M. Virmond, B. Flageul, S. N. Cho, B. Ji, A. Paniz-Mondolfi, J. Convit, S. Young, P. E. Fine, V. Rasolofo, P. J. Brennan, and S. T. Cole. 2005. On the origin of leprosy. Science 308:936-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrocinio, L. G., I. M. Goulart, L. R. Goulart, J. A. Patrocinio, F. R. Ferreira, and R. N. Fleury. 2005. Detection of Mycobacterium leprae in nasal mucosa biopsies by the polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 44:311-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plikaytis, B. B., R. H. Gelber, and T. M. Shinnick. 1990. Rapid and sensitive detection of Mycobacterium leprae using a nested-primer gene amplification assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1913-1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridley, D. S., and W. H. Jopling. 1966. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 34:255-273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rinke de Wit, T. F., S. Bekelie, A. Osland, B. Wieles, A. A. Janson, and J. E. Thole. 1993. The Mycobacterium leprae antigen 85 complex gene family: identification of the genes for the 85A, 85C, and related MPT51 proteins. Infect. Immun. 61:3642-3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rondini, S., E. Mensah-Quainoo, H. Troll, T. Bodmer, and G. Pluschke. 2003. Development and application of real-time PCR assay for quantification of Mycobacterium ulcerans DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4231-4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reference deleted.

- 19.Santos, A. R., A. B. De Miranda, E. N. Sarno, P. N. Suffys, and W. M. Degrave. 1993. Use of PCR-mediated amplification of Mycobacterium leprae DNA in different types of clinical samples for the diagnosis of leprosy. J. Med. Microbiol. 39:298-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scollard, D. M., T. P. Gillis, and D. L. Williams. 1998. Polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection and identification of Mycobacterium leprae in patients in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 109:642-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shepard, C. C., and D. H. McRae. 1968. A method for counting acid-fast bacteria. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 36:78-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shrestha, N. K., M. J. Tuohy, G. S. Hall, U. Reischl, S. M. Gordon, and G. W. Procop. 2003. Detection and differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial isolates by real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5121-5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith, W. C., C. M. Smith, I. A. Cree, R. S. Jadhav, M. Macdonald, V. K. Edward, L. Oskam, S. van Beers, and P. Klatser. 2004. An approach to understanding the transmission of Mycobacterium leprae using molecular and immunological methods: results from the MILEP2 study. Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 72:269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stefani, M. M., C. M. Martelli, T. P. Gillis, and J. L. Krahenbuhl. 2003. In situ type 1 cytokine gene expression and mechanisms associated with early leprosy progression. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1024-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres, P., J. J. Camarena, J. R. Gomez, J. M. Nogueira, V. Gimeno, J. C. Navarro, and A. Olmos. 2003. Comparison of PCR mediated amplification of DNA and the classical methods for detection of Mycobacterium leprae in different types of clinical samples in leprosy patients and contacts. Lepr. Rev. 74:18-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, L., T. Budiawan, and M. Matsuoka. 2005. Diversity of potential short tandem repeats in Mycobacterium leprae and application for molecular typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5221-5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]