Abstract

This paper highlights the southwest Asian country of Georgia's experience in creating efforts to protect and promote breastfeeding and to implement the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. Since 1994, the country of Georgia (of the former Soviet Union) has successfully implemented the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative. In 1997–1998, Georgia conducted a study throughout the country's various regions to evaluate compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. The research demonstrated numerous violations of the code by various companies and confirmed the necessity of ongoing activities to promote implementation of the code. Due to the great effort of Georgia's Ministry of Health and the International Baby-Food Action Network [IBFAN] Georgian group called “Claritas,” the law titled “On Protection and Promotion of Breastfeeding and Regulation of Artificial Feeding” was adopted in 1999 by the country's parliament. As a result, Georgia has witnessed a sharp increase in breastfeeding percentages, the designation of baby-friendly status at 14 maternity houses, and a decrease in the advertisement of artificial-feeding products.

Keywords: breast-milk substitutes, international legislation, breastfeeding, baby-friendly

Background

In 1991, UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) established that the healthiest feeding practice for infants is exclusive breastfeeding up to 6-months of age, and continuing to breastfeed from the 6-month introduction of adequate complementary food for up to 2 years or beyond. Babies and their mothers, families, community, and the environment—even the economy of the country in which they live—all benefit from breastfeeding.

The country of Georgia (of the former Soviet Union and located in southwest Asia) has a long-standing history of breastfeeding. In recent years, however, despite the widely acknowledged benefits of breastfeeding, Georgia witnessed a sharp decline in infant breastfeeding practices and an increase of high dependence on breast-milk substitutes. The reasons for these trends were numerous. Some of the more significant influences were as follows: In recent years, Georgian health facilities promoted far less than ideal breastfeeding practices (rooming-in was rare and immediate initiation was nonexistent); the importation and distribution of breast-milk substitutes became common due to the consequences of a social economic crisis in Georgia; and the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes, which represented the main tool available to protect breastfeeding against the baby-feeding industry's aggressive marketing practices, was completely ignored. The sharp increase in the use of breast-milk substitutes contributed to the country's increased infant morbidity and mortality. In 1993, Georgia's child health indices and breastfeeding rates were as follows:

Infant mortality rate – 17.9% per 1,000 live births

Breastfeeding (nonexclusive) rate at one month – 20%

Breastfeeding at 6 months – 3.3%

Georgian government officials and foreign experts expressed concern that the country's nutrition dependence on companies that manufactured breast-milk substitutes was developing. Consequently, health benefits associated with breastfeeding were being lost as breastfeeding rates dropped. Breastfeeding was identified as an urgent societal need in order to insure better, more secure food sources for infants in Georgia and to reduce dependence on formula donations.

Breastfeeding was identified as an urgent societal need in order to insure better, more secure food sources for infants in Georgia and to reduce dependence on formula donations.

Since 1994, Georgia has successfully implemented a breastfeeding program. The country also launched a campaign to vitalize breastfeeding activities by implementing the UNICEF/WHO Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI; see Box). This initiative has created a broad base of support for breastfeeding in Georgia. Breastfeeding and BFHI have received the interest of Georgia's Ministry of Health because of their positive effect on the survival rates of children. As national breastfeeding promotion efforts and BFHI implementation got underway, it became increasingly clear that a need existed to control the influx and distribution of breast-milk substitutes. Thus, Georgia undertook actions to promote the implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.

Box. UNICEF/WHO Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative: Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding*.

To become a Baby-Friendly Hospital, every facility providing maternity services and care for newborn infants should:

Have a written breastfeeding policy that is routinely communicated to all health-care staff.

Train all health-care staff in skills necessary to implement this policy.

Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding.

Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within half an hour of birth.

Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to maintain lactation even if they should be separated from their infants.

Give newborn infants no food or drink other than breastmilk, unless medically indicated.

Practice rooming-in—allow mothers and infants to remain together 24 hours a day.

Encourage breastfeeding on demand.

Give no artificial teats or pacifiers (dummies or soothers) to breastfeeding infants.

Foster the establishment of breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them on discharge from the hospital or clinic.

Conducting an accurate evaluation of compliance with the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes and obtaining the objective data of code violations in Georgia were critical steps for preventing ongoing code violations. The International Baby-Food Action Network (IBFAN) has an affiliated group in Georgia called “Claritas,” a nongovernmental organization (NGO). In 1997–1998, UNICEF conducted an international monitoring project of the code. The organization asked Claritas to coordinate an active monitoring effort in Georgia on behalf of Wemos (a Dutch agency that promotes health and development). Results of this monitoring project in Georgia demonstrated that marketing practices used by sales representatives and distributors of baby-feeding products were in breach of the code. Results also showed that many sales representatives engaged in code violations such as displaying posters that advertised milk-substitute products, distributing incorrect information, and providing gifts along with purchased products. Code violations also existed in health-care facilities that received free supplies labeled as “humanitarian aid” and provided these as samples to mothers. The monitoring project's findings confirmed the need for legislation to implement the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.

Results of the group's monitoring project demonstrated that marketing practices used by sales representatives and distributors of baby-feeding products were in breach of the code.

Georgia's goal was to insure the establishment of safe, natural infant feeding by promoting awareness of the code and ensuring code compliance through regulation of the marketing strategies for infant-feeding products. The country's campaign focused on providing education on the code, arranging meetings at different levels, and popularizing the code. It was very important to persuade different levels of Georgia's society about the importance of the code as an instrument to protect the most vulnerable members of society— mothers and children—from the negative influence of the baby-food industry and the dangers caused by artificial feeding. The campaign targeted governmental structures, insisting that an optimal period existed in Georgia for code ratification. It was also pointed out that ratifying the code would give Georgia the opportunity to avoid inevitable problems of the future, guaranteed by the developing local industry and the expected, massive expansion of the breast-milk substitute manufacturing companies. Due to the efforts of Georgia's Ministry of Health, the IBFAN Georgian group Claritas, the active support of international partner organizations (IBFAN, Baby-Milk Action, Wemos, etc.), and the persistence of many lobbying activities, the campaign has successfully achieved considerable impact at the level of health workers, government authorities, and mass media (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Successful Efforts in Various Arenas that Impacted Georgia's Breastfeeding Campaign

| Arena | Successful Efforts and Activities |

|---|---|

| Health Workers | • Training |

| • Private dialogues | |

| • Protests staged at conferences sponsored by companies promoting breast-milk substitutes | |

| • Student action in the streets | |

| Government Authorities | • Private dialogues |

| • Distribution of informational material | |

| • Lobbying, with the help of the Georgian President's Decree #1 | |

| • Eurodirectives | |

| Mass Media | • Code-supporting articles in newspapers and medical magazines |

Georgia's Ministry of Health collaborated with Claritas to draft the law “On Protection and Promotion of Infants' Natural Feeding and Artificial Feeding Controlled Use.” After three hearings, the Georgian Parliament adopted the law and, on September 9, 1999, the law was approved. It reflects almost all the provisions of the international code and, thus, can be considered a strong instrument of breastfeeding protection in Georgia (see Table 2). It protects a mother's right to choose the method of feeding for her baby on the basis of objective and available, complete information on the advantages of breastfeeding. The law also contains provisions to protect children from low-quality and improper nutrition (elaborated on the basis of the Codex Alimentarius Commission's set of international food standards).

Table 2.

Provisions Mandated by Georgia's Law “On Protection and Promotion of Breastfeeding and Regulation of Artificial Feeding”

| Protect Mother-Child Rights | Protect Health Workers' Rights and Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| • Provide mothers with proper information on breastfeeding. | • Provide opportunities for health workers to protect and promote breastfeeding of infants. |

| • Prohibit breastfeeding depreciation and artificial-feeding advertising information. | • Prohibit the following items offered by artificial-feeding companies: free and low-cost supplies and samples of artificial-feeding products and brands; financial support; and sponsorship of scientific or medical activities. |

| • Provide high-quality artificial-feeding products by ensuring imported and locally produced food compliance with Codex Alimentarius and state standard (infant feeding formula #1) requirements. |

The country's new law has become a strong instrument of breastfeeding protection and promotion in Georgia.

Georgia's new law created a supervisory council led by the deputy chair of the country's ministry of health. This element is a crucial factor in the follow-up stage of the legislation. The council includes representatives from almost every ministry, the national coordinator of breastfeeding, and Claritas members. Its main function is to facilitate the execution of the law by supervising the accuracy of all the informational materials on infant feeding, raising the public's educational level on baby-adequate nutrition issues, and constantly observing compliance to the law. The law modified the code on advertising, particularly the phrase of the seventh article, which states, “It is prohibited to advertise and propagandize in any form of children artificial-feeding products, except complementary food.” The Georgian law's implementation process also requires monitoring of the antimonopoly department, which is included in the supervisory council.

Subsequently, Claritas presented the council with reports of observed law violations. The council then delivered warning letters (signed by the health minister) to the responsible parties. This procedure has turned out to be effective. The violations concerning advertising, as reported by Claritas, were stopped with the assistance of the antimonopoly department. As a result, artificial-feeding companies' practice of providing free samples and supplies, as well as advertising their products in health facilities and disseminating propaganda in mass media, has ceased in Georgia. Some violations of the law still exist. For example, not all products provide labels in the Georgian language and some health-care workers sponsor baby-food producing companies (see Table 3). These actions require constant monitoring and proper reaction (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Georgia's Law “On Protection and Promotion of Breastfeeding and Regulation of Artificial Feeding”—Pre- and Postlaw Situations

| Prelaw | Postlaw |

|---|---|

| Low-quality, expired artificial-feeding products were commonly marketed. | Law requirements demand customs control on the quality of imported artificial-feeding products and compliance with the state standard for infant formula. Consequently, a significant decrease has occurred in the exporting and marketing of low-quality products. |

| Information provided on labels of artificial-feeding products was usually presented in different languages. In some instances, varying information was provided in different languages (e.g., German language indicated “from 4 months of age” whereas Russian language indicated “from 2 months of age”). | • The mass media publicized the law. Antimonopoly and customs departments were engaged in the process. |

| • Most artificial-feeding products provide labels translated into Georgian; thus, the risk of improper preparation of products is reduced. | |

| Inadequate product—sour-milk mixture product (“matsoni”)—was widely used for feeding of infants aged below 6 months. | According to the requirements of the law (as mandated by the Ministry of Labor's Health and Social Affairs Department), the sour-milk mixture product (“matsoni”) was declared complementary food for babies aged over 6 months. For poor regions, elaborate instructions are provided for dilution of cow's milk when used as a breast-milk substitute. |

| Bottles with teats were widely used for artificial feeding of infants. | Using the proper population information, advertisements for bottles and teats are prohibited, according to law requirements. Feed-cup use is encouraged and appropriate information is disseminated. |

| A homeopathic remedy (Apic-Mellifica 9CH-brionia Alba 9CH, produced by BOIRON laboratories) was delivered to the Ministry of Labor's Health and Social Affairs Department. It was evaluated for its efficacy and safety among women attempting to dry up their milk supply during the immediate postpartum period. | On the basis of the law—which states that every issue concerning lactation and infant feeding should be agreed upon by the national supervising council—and according to the council's demands, the ministry made the following decision: Approval of the preparations is given only for those women who are unable to breastfeed their babies due to medical contraindications of the mother or baby. The results of having given approval must be delivered to the national supervising council for evaluation. |

| In one maternity house of Tbilisi, mothers received a free box of an artificial-feeding product along with free newborn cloths that displayed the phrase “I Love My Mommy” and the name brand “Nestlé.” | A letter of protest was sent to the chief doctor of the maternity house and provided an explanation of the law violation. This action resulted in a halt of the process. |

Table 4.

Georgia's Law “On Protection and Promotion of Breastfeeding and Regulation of Artificial Feeding”—Some Violations that Still Require Monitoring and Appropriate Reaction

| Constraints | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|

| • Cases of artificial-feeding companies' bribery and sponsorship among health-care workers are difficult to prove. | • Strengthen monitoring efforts and procedures. |

| • Incomplete awareness of the law's provisions still exists. | • Intensify the law's information provision. |

| • Health-care authorities at several maternity houses still resist implementing the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative and law provisions. |

Summary

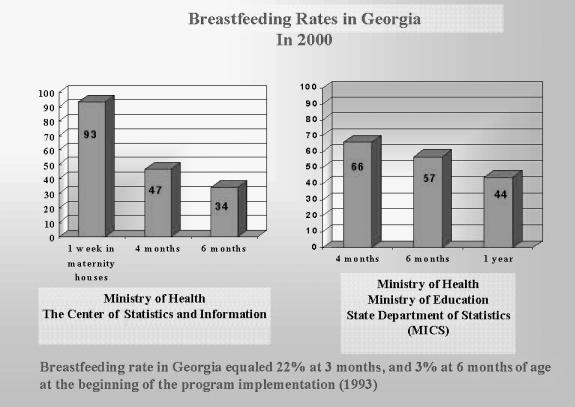

Currently, Georgia has experienced a sharp increase in the breastfeeding percentage rate (see Figure). Out of 78 maternity houses, 14 have earned baby-friendly status. Despite the implementation of code/law procedures, much more needs to be done to promote breastfeeding as the normal lifestyle for every woman and to designate all maternity hospitals as baby-friendly, thus ensuring full realization of the Georgian law. Factors that have proven most helpful in moving the breastfeeding campaign forward to achieve these goals are presented in Table 5. The Figure shows the improved breastfeeding rates based on data from two different agencies.

Breastfeeding Rates in Georgia in 2000

Table 5.

Helpful Factors at Different Levels that Increased the Success of Georgia's Breastfeeding Campaign

| Level | Arena | Helpful Factors |

|---|---|---|

| International | International humanitarian NGOs | 1. The existence of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes |

| 2. An active international campaign | ||

| National | • President of Georgia | • Progressive vision of the president and some government authorities |

| • National government | • Ministry of Health support | |

| • Local NGOs | • Absence of local manufacturers | |

| • Public awareness | ||

| • Monitoring | ||

| Grassroots | • Communities | • Public Awareness |

| • Families | • Active individuals | |

| • Individuals |

According to Georgia's experience, implementing widespread promotion of breastfeeding and the BFHI program is feasible. It takes an initial stage of education and popularization—on every level of society—of breastfeeding, the BFHI, and the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. Code monitoring is a crucial factor to establishing the need for a law and to monitoring implementation of the law. Consequently, the result of this effort is to save one of the most crucial rights of a child—to be provided with safe and adequate nutrition, such as breastfeeding.

Footnotes

*UNICEF and the World Health Organization. (1991). The baby-friendly hospital initiative. Retrieved May 20, 2003, from http://www.unicef.org/programme/breastfeeding/baby.htm#10