Abstract

New fathers (men whose partners had recently given birth) were asked to indicate to what degree antenatal classes had prepared them for childbirth, for their role as support persons, and for lifestyle and relationship changes after the birth. These postbirth findings were compared with a previous exit survey of male attendants at antenatal classes in which fathers-to-be predicted that the antenatal classes had prepared them well on all fronts. The new fathers in this study, however, reported that the antenatal classes had prepared them for childbirth but not for lifestyle and relationship changes after the birth. Additionally, couples who attended antenatal classes were asked to what extent they were familiar with family-related services in the region and how often they had used these services since the birth of their baby. Fathers were less familiar than mothers with the family-related services.

Keywords: perinatal education, new fathers, family-related services

Introduction

In preparation for the childbearing process, approximately 80% of first-time parents in Australia attend antenatal/childbirth and parenting education courses (New South Wales Standing Committee on Social Issues, 1998). Yet, despite the recognition of the positive role fathers can play during pregnancy, labour, and childbirth, as late as the early 1990s few Australian programs provided support specifically for fathers that would encourage their increased involvement (Edgar & Glezer, 1992). Furthermore, from the late 1980s, one of the most consistent themes underpinning investigations of fathers' roles in the lives of their children has been the growing awareness of the benefits that positive father involvement has for child development. This growing awareness of the advantages of paternal involvement has led to greater recognition of the support needs of men during their transition to fatherhood, from the antenatal period through early childhood and beyond.

However, fathers are not currently accessing existing family-related services. While the literature cites possible barriers to fathers' involvement in such services, the evidence as to how better to meet these needs is far from clear.

In an attempt to address this issue, the aim of this research project was twofold: first, to assess how well antenatal classes currently being offered in the Hunter region of New South Wales (NSW), Australia, are meeting men's needs and, second, to assess new fathers' familiarity with and use of support services. This latter information would then be used to formulate strategies so that men are better supported in their roles as labour support person, parent, partner, and family member.

Review of Literature

While the benefits of constructive father involvement in the lives of their children are now well-recognised and well-documented (Bernadette-Shapiro, Ehrensaft, & Shapiro, 1996; Lamb, 1997; McBride & Rane, 1996; Nord, 1998), the benefits of fathers' involvement with their families actually begins well before their child is born. The positive contribution expectant and new fathers can make has been recognised for many years as valuable to the mother's well-being during pregnancy, labour, and childbirth (Entwisle & Doering, 1988; Kroelinger & Oths, 2000; May, 1982).

Not only is there a growing recognition of the role of fathers from pregnancy through labour, childbirth, and infancy, fathers are also now demanding a greater role in these early stages. Consequently, a need exists to better understand the experiences of fathers and support them in the transition from expectant to new fathers. This desire for greater involvement and recognition has aptly been labeled as “laboring for relevance” (Jordan, 1990, p. 11).

A need exists to better understand the experiences of fathers and support them in the transition from expectant to new fathers.

In conjunction with the recognition of the positive benefits of fathers' involvement and changes in the pattern of societal beliefs about gender roles, an acceptance has emerged that fathers' needs are identifiable (Fletcher, 1995). These include issues associated with the needs of men during the antenatal period that may be separate and additional to those of the expectant mother. Of particular importance is the recognition that the individual needs of men must be considered in their preparation and education for new fatherhood and changing family dynamics. As a consequence, greater attention is now being paid to fathers who, in the past, have been largely excluded from consideration in both the reproductive and childbearing process (Jordan, 1990).

For those men who attended antenatal classes, reactions—including feelings of frustration, helplessness, anxiety, discomfort, nervousness, and fear for their partners—are well documented (Chapman, 2000; Henderson & Brouse, 1991; Nichols, 1993; Shapiro, 1987; Smith, 1999). Underpinning these reactions is a lack of consideration for the needs of men, so they simply feel like observers in a women's class (Smith, 1999). Similarly, an Australian study of men attending antenatal classes found that men “were alienated in the manner in which information was presented” (Barclay, Donovan, & Genovese, 1996, p.12), because classes tended to focus on their partners. These authors concluded that “antenatal education was endured and not enjoyed by most men, and the finding that men often resented and tolerated the ways in which information was provided, indicates that health services are not meeting most men's needs” (p. 23). This view was supported by Shapiro (1995) who found that fathers' presence at antenatal visits is viewed as “cute or novel,” with little or no information about their changing identity and future role; therefore, fathers and male participants often only attend out of a duty to their partners (Hallgren, Kihlgren, Forslin, & Norberg, 1999).

In contrast to these findings, Galloway, Svensson, and Clune (1997), who surveyed expectant fathers while they were attending antenatal classes, found most expectant fathers “… felt more confident about their role as a support person in labour, better prepared for the changes in lifestyle after the birth and that they had opportunities to talk about issues that were important to them” (p. 38). The investigators acknowledged, however, that the expectant fathers might not have been able to accurately assess the value of the program, as it existed, without the benefit of the experience of their partner's labour and the period after childbirth.

While antenatal classes may attempt to prepare both men and women for the actual birth, courses generally do not prepare either women or men for the emotional and psychological aspects of parenthood (Barclay et al., 1996; Brown, Lumley, Small, & Astbury, 1994; Donovan, 1995), which are often more important than the physical issues (Knauth, 2000; Parr, 1988). From Australian research, Barclay and Lupton (1999) reported that, for most men, first-time fatherhood involves significant changes both in self-identity and their relationship with their partner, and the amount of tension the birth caused in their relationship greatly surprised men. Donovan (1995) also recognised that little is known about the experiences of Australian men during their partner's pregnancy, concluding that “emotional turmoil and anxiety in men contributed to the ‘mismatch’ in male and female expectations of the relationship” (p. 708). Men want reassurance that everything in their relationship will return to normal once the baby is born; however, this topic is seldom discussed because men's needs are rarely acknowledged or supported (Donovan, 1995).

Another area now receiving greater recognition is the support men need during their transition to fatherhood. Traditionally, support services for parents from the antenatal period onward have focused on women or have been labeled as directed toward the family, which in reality may again focus on the mother. Only in the past few years have specific support services been directed toward the needs of fathers: for example, the American “Boot Camp for New Dads” (Alexander, 2000) and the Australian “Man… Being a Father” (Denner, 1998) programs. However, with few exceptions (Gross, Fogg, & Tucker, 1995; McBride, 1991), the effectiveness of these services has received little rigorous or systematic examination.

Large numbers of fathers are not currently accessing existing family-related support services. Evidence in the literature suggests several reasons for this, as identified by Fletcher, Silberberg, and Baxter (2001) in an extensive review of the literature. The reasons included the following: barriers within the services themselves, such as ambivalence about increasing father involvement; little focus on men's roles; a failure to recognise fathers in family-service settings; lack of skills for engaging men; few opportunities for men to relate to other men; a preoccupation with medical rather than fathering information; and the timing of classes where information is not presented when most needed. Added to these barriers are fathers' negative attitudes to services in their current format, mothers who act as “gatekeepers” of childbirth and child-rearing knowledge, and, on a broader scale, negative stereotypical images of men as nurturers.

From the literature on pregnancy, labour, childbirth, and childcare, it is clear that, while conditions and perceptions are slowly changing, fathers' needs are not being met. Even in those programs where attempts have been made to engage fathers, few have attempted to assess the benefits after the period of childbirth. Similarly, fathers are not currently engaging family-related services, and those studies that have attempted to identify their support needs have yielded little useful information. This study attempted to address some of these issues.

From the literature on pregnancy, labour, childbirth, and childcare, it is clear that, while conditions and perceptions are slowly changing, fathers' needs are not being met.

New Fathers' Study

Purpose

The purpose of the section of the research project reported here1 was twofold. The first was to evaluate new fathers' reactions to antenatal classes after the experience of labour and childbirth. The second purpose was to identify the reasons why new fathers do not currently access services that are available to support them in their role as parents/carers and to identify strategies to support more men in these roles.

Participants

Couples who attended antenatal classes at the John Hunter Hospital, located in NSW, Australia, in 2000 were invited to participate in the study. Names and addresses were obtained from the class records. The survey packages were distributed around the Hunter region to couples who attended at least 50% of the antenatal classes and had indicated on hospital records that this was the mother's first child (n = 691). Approval for this research was given by The University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee.

Data Collection and Instruments

The survey package contained an explanatory letter to both the mother and the father, a Request-for-Feedback Form (to receive a summary of the study's results) for each, a New Fathers Survey, and a New Mothers Survey. Additionally, the fathers received an expression-of-interest form to fill out if they were interested in attending future antenatal classes to share their experiences with expectant parents.

Both the New Fathers Survey and the New Mothers Survey were developed for this project. The New Fathers Survey consisted of six closed and two open questions—some with multiple parts—while the survey for the mothers had only two questions. Question 1 on both surveys collected demographic details on the participants' age, baby's age, and whether the baby was their first child. The latter was included because, even though surveys were sent only to those couples for whom this was the mother's first child, the hospital does not collect this information from fathers.

Question 2 on the mother's form and Question 7 on the father's form listed 11 family-related services available in the Hunter region. The participants were asked to indicate whether they were familiar with each service and to what degree they had used that service since the birth of their baby (once, more than once but less than four times, four times or more). This question was devised to test the hypothesis that women are more familiar with support services than men and that women access these services more frequently than men.

The New Fathers Survey had five additional questions (see Table 1). Question 2, answered on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree), comprised four statements adapted from an exit survey (Galloway et al., 1997) completed by men who attended antenatal classes in three major hospitals in NSW. The results of Question 2 could then be compared with the results of Galloway and colleagues' 1996 Exit Survey to determine if any discrepancies occurred between prediction/expectation and actual experience.

Table 1.

Additional Questions in New Fathers Survey

| Question 22 |

| a) Attending the antenatal classes helped me feel more confident during the birth of our baby. |

| [Attending the classes has helped me to feel more confident about the impending birth.] |

| b) Attending the antenatal classes helped me feel more confident as a support person during my partner's labour. |

| [I feel more confident now for my role as a support person in labour.] |

| c) The antenatal classes prepared me well for the changes in lifestyle after our baby was born. |

| d) The antenatal classes prepared me well for the relationship changes after the birth of our baby. |

| [I feel better prepared for the changes that will happen to our lifestyle after the birth of our baby.] |

| Question 3 |

| After the birth of your baby, have you remained in contact with any of the couples who attended the antenatal classes with you? |

| • Yes – Could you tell us some more about this contact (i.e., the frequency and the type or format of contact)? |

| • No |

| Question 4 |

| If a service offered postnatal classes to provide information about baby care, parenting, managing the changes in lifestyle, relationships, etc., and these classes were held after hours for mothers and fathers, would you sign up and attend these classes? |

| • Yes |

| • No – Could you elaborate on the reasons why you would not attend postnatal classes? |

| Question 5 |

| Would you accept an invitation from the antenatal educator to share your experiences as a new father with the fathers-to-be during an antenatal class session? |

| • Yes – See expression-of-interest form. |

| • No |

| Question 6 |

| When you have queries about fathering your baby, who do you turn to? (You can tick more than one box.) |

| • Partner |

| • Mother/Mother-in-Law |

| • Father/Father-in-Law |

| • Brother/Brother-in-Law |

| • Sister/Sister-in-Law |

| • Fellow Father |

| • Male Friend |

| • Female Friend |

| • General Practitioner |

| • Child Health Nurse |

| • Other |

The statements in brackets refer to the Exit Survey (Galloway, Svenson, & Clune, 1997).

Question 3 (Yes/No response) assessed whether the attendance at the antenatal classes had any social benefits such as friendships, social gatherings, and other opportunities. Question 4 (Yes/No response) was devised to determine the level of interest in follow-up classes after the birth as a possible means of providing education to new fathers. Both these questions had space for fathers to elaborate on their answers. Question 5 (Yes/No response) provided an indication as to whether new fathers would be willing to be involved in antenatal education. Lastly, Question 6 (tick relevant box) provided an indication as to where new fathers seek answers to fathering questions; their responses were to be used to devise strategies to disseminate information on fathering.

Analysis

Data were initially analysed using descriptive statistics. For Question 2, chi-square analysis was used to determine whether new fathers' impressions of the antenatal classes differed significantly from those of expectant fathers. For the question on the awareness and use of services, the responses of the fathers and mothers were compared using chi-square analysis to test the hypothesis that mothers are more familiar with family-related services and access them more frequently than fathers. On the question regarding fathers' interest in attending postnatal classes and to whom they turn with queries about fatherhood, descriptive statistics were derived. Open-ended questions provided information on the social benefits of attending antenatal classes and the fathers' willingness to return to an antenatal class to share their experiences or their reasons for not wishing to participate further. Content analysis was used for these responses.

Results

Of the 691 couples who were sent a survey package, 32 couples had moved to another address since the birth of their baby and were lost to potential follow-up efforts. Of the remaining 659 couples, 213 (32.3%) provided responses. In general, both the father and the mother participated in the study. In six cases, only one member of the couple returned the survey. In total, 212 fathers and 216 mothers participated. Of these, 95% were first-time fathers and 97% were first-time mothers. Although surveys were sent only to those mothers who, according to hospital records, were having their first child, six mothers indicated to us that this was not their first child. This gave a 3% discrepancy rate between the hospital records and the survey responses, the reasons for which are indeterminate. As mentioned above, parity of fathers who did not return the surveys is unknown. Survey responses indicated their baby's age was 0–6 months (29%), 7–12 months (42%), and older than 12 months (29%). The fathers' ages ranged from 21–52 years (M = 32.1, SD = 5.17) and the mothers' from 20–45 years (M = 29.6, SD = 4.39).

Table 2 shows the responses to Question 2. The responses to the New Fathers Survey are reflections on the benefits of antenatal classes up to one year after the birth of the baby, while the responses to the Exit Survey are predictions of those fathers-to-be who completed the survey immediately after attending antenatal classes. As the table shows, both groups agreed that antenatal classes helped them feel more confident during labour (88.3% and 89.0%, respectively) and more confident in their role as a support person (87.2% and 90.5%, respectively). For the question about lifestyle and relationship changes, however, a discrepancy occurred between prediction and actual experience: 73.5% of the fathers-to-be agreed that the antenatal classes prepared them well for the upcoming changes, but only 29.8% of the new fathers agreed that the classes had prepared them well for lifestyle changes and 27.8% for relationship changes. On both aspects of this question, the New Fathers Survey and the Exit Survey were significantly different at the .01 level.

Table 2.

Benefits of Antenatal Classes—New Fathers Survey (n = 212) and Exit Survey (n = 200) (percent)

| Question | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Chi-square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a) Confidence during birth | ||||||

| New Fathers Survey | 37.1 | 51.2 | 10.2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | |

| Exit Survey | 35.0 | 54.0 | 8.0 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 1.92 |

| 2b) Confidence as a support person | ||||||

| New Fathers Survey | 34.5 | 52.7 | 9.4 | 2.0 | 1.5 | |

| Exit Survey | 36.5 | 54.0 | 7.5 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.18 |

| 2c) Lifestyle changes | ||||||

| New Fathers Survey | 5.9 | 23.9 | 39.5 | 23.4 | 7.3 | |

| Exit Survey (lifestyle and relationship changes) | 17.0 | 56.5 | 22.5 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 87.69* |

| 2d) Relationship changes | ||||||

| New Fathers Survey | 6.3 | 21.5 | 35.6 | 29.8 | 6.8 | |

| Exit Survey (lifestyle and relationship changes) | 17.0 | 56.5 | 22.5 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 100.53** |

Note. For the chi-square analysis, the “Disagree” and “Strongly Disagree” categories were collapsed into one category.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Forty-nine (24%) new fathers referred to some form of social contact with other participants of the antenatal classes. Of these, nine referred to making social contact only once at a reunion organised by the hospital and the remaining 40 (19%) referred to regular and continuous contact. Seven fathers reported that their wives regularly met with the other mothers, but only one father referred to men-only contact as a social spin-off from the classes.

When asked if they would attend postnatal classes, 120 fathers (59%) indicated they would attend if they were offered after business hours. Of those fathers who were not interested, 17.6% gave no reason. However, those who did offer explanations cited a variety of reasons, the most frequent being lack of time (29.4%); no need for extra support because they were coping well (15.3%); access to other support resources such as books, support groups, a general practitioner, a child health nurse, friends, and family (11.8%); location and travel time (4.7%); learning through experience (4.7%); and timing—the need was there immediately after the birth but not now (3.5%). Approximately one-quarter of the fathers (26.2%) expressed an interest in sharing their experiences with fathers-to-be at future antenatal classes.

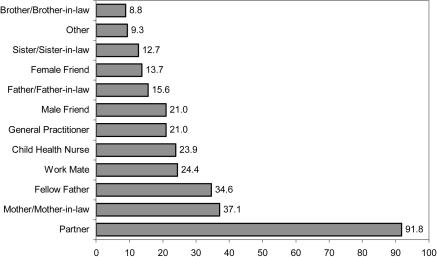

The responses to the question of whom they turn to when they have queries about fatherhood are shown in Figure 1. The majority (91.8%) responded that they turn to their partners. Other sources of information included mother-in-law/mother (37.1%), fellow fathers (34.6%), work mates (24.4%), child health nurse (23.9%), general practitioner (21.0%), and father-in-law/father (15.6%).

Fathers' Use of Informants on Questions about Fatherhood (percent who used service)

The results of the question on awareness and use of services, which appeared on both the New Fathers Survey (Question 7) and the New Mothers Survey (Question 2), are presented in Table 3. For all but three services (general practitioner, early childhood clinic, and poison information centre), 50% or more of the fathers were unfamiliar with the service. This compared with the mothers who were similarly unfamiliar with only three of the 11 services (family support service, home start, and family relationship skills program). The chi-square analysis showed a statistically significant difference between the mothers and fathers on 10 of the 11 services (nine at .01 and one at .05 level of significance). The data supported the hypothesis that mothers are more familiar with family-related services than fathers.

Table 3.

Fathers and Mothers Unfamiliar with Support Services (percent)

| Support Service | Fathers (n = 212) | Mothers (n = 216) | Chi-square |

|---|---|---|---|

| General practitioner | 2.4 | 0.0 | 5.17* |

| Early childhood clinic | 9.0 | 5.0 | 17.44** |

| Family Care Cottage | 62.3 | 28.2 | 50.75** |

| Family Support Service | 70.3 | 56.9 | 8.63** |

| Home Start | 86.3 | 75.0 | 9.47** |

| Postnatal depression services | 57.5 | 30.1 | 33.34** |

| Family Relationship Skills Program | 92.5 | 88.0 | 2.99 |

| Kids Kare Line | 61.8 | 33.8 | 34.24** |

| Tresillian Help Line | 58.5 | 18.5 | 73.09** |

| Karitane Help Line | 83.0 | 42.6 | 79.10** |

| Poison Information Centre | 41.5 | 25.5 | 12.64** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

The other aspect of this question was how often, if at all, fathers and mothers accessed those services with which they were familiar. Examining only those mothers and fathers who where familiar with the service, the use patterns are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Access Patterns by Fathers and Mothers to Family-Support Services (percent)

| Fathers |

Mothers |

Chi-Square |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Services | n | not used | 1 | 2–3 | >4 | n | not used | 1 | 2–3 | >4 | |

| General practitioner | 206 | 22.8 | 9.7 | 38.8 | 28.6 | 216 | 1.9 | 4.6 | 39.4 | 54.2 | 58.67** |

| Early childhood clinic | 192 | 28.6 | 9.9 | 18.2 | 43.2 | 215 | 3.7 | 1.4 | 10.7 | 84.2 | 84.53** |

| Family Care Cottage | 79 | 78.5 | 13.9 | 7.6 | 155 | 71.6 | 16.1 | 12.3 | 1.56 | ||

| Family Support Service | 62 | 95.2 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 93 | 95.7 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.92 | |

| Home Start | 28 | 85.7 | 3.6 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 54 | 90.7 | 1.9 | 7.4 | 2.21 | |

| Postnatal depression services | 89 | 97.8 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 151 | 87.4 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 7.90* | |

| Family Relationship Skills Program | 15 | 93.3 | 6.7 | 26 | 100.0 | 1.78 | |||||

| Kids Kare Line | 80 | 86.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 143 | 81.8 | 12.6 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 3.19 |

| Tresillian Help Line | 87 | 79.3 | 11.5 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 176 | 64.2 | 18.2 | 12.5 | 5.1 | 6.33* |

| Karitane Help Line | 35 | 97.1 | 2.9 | 124 | 86.3 | 8.9 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 4.82 | ||

| Poison Information Centre | 123 | 99.2 | 0.8 | 161 | 93.8 | 5.0 | 0.6 | .06 | 7.12 | ||

p < .05.

p < .01.

Mothers accessed four services significantly more often than fathers: general practitioner (p < .01), early childhood clinic (p < .01), postnatal depression service (p < .05), and Tresillian Help Line (p < .05). However, most of the remaining services, while familiar to either or both parent, had been accessed very little since the birth.

Fathers felt they were well prepared for the birth and their role as support person. However, they felt less well prepared for the relationship and lifestyle changes accompanying the arrival of a new baby.

Discussion

The survey of fathers some months after the birth of their child provides an evaluation of the effectiveness of antenatal education programs being conducted in the Hunter region of NSW in Australia during the previous year. In contrast to the study by Galloway and colleagues (1997), the study described here sought the reactions of fathers after the experience of childbirth and fatherhood and then compared them with the immediate post-class predictions of fathers who had attended similar antenatal classes.

On several counts, the antenatal classes were evaluated as being very successful. Fathers felt they were well-prepared for the birth and their role as support person. In this respect, the findings of this study support those of Galloway and colleagues (1997). However, fathers felt less well prepared for the relationship and lifestyle changes accompanying the arrival of a new baby, an outcome that echoes findings in the literature. A clear mandate exists here for reviewing the curriculum of antenatal classes to incorporate more emphasis on relationships and to review the timing of the presentation of this information.

With regard to timing, parents appear more receptive to information delivered when it is most needed; for example, Australian research suggests that both parents are not predisposed to absorb information about postnatal support services during the prenatal period (Harris, 1990; Russell, 1986). Similarly, both men and women are possibly so preoccupied with the issues of labour and childbirth that they are not ready to absorb information on relationship and lifestyle changes until the challenge becomes a reality. A better time for the delivery of this information may be immediately after the birth. In contrast, Canadian researchers have found the second trimester of pregnancy to be an effective time for teaching some aspects of postpartum adjustment (Midmer, Wilson, & Cummings, 1995).

Some potential is evident for enhancing the development of social networks through the classes. With over one-third of male participants indicating they turn to a fellow father for parenting advice, the development of these networks could provide valuable contacts and sources of support.

The finding that approximately 60% of the fathers expressed an interest in attending postnatal classes provides an approximate indication of interest. Since the survey participants were recruited from across the lower Hunter Valley and were not asked for commitment to specific classes, attendance at postnatal classes should not be assumed. Nevertheless, at the present time, no provision is available for fathers in the postnatal education area. This survey provides encouragement to pilot an educational program for fathers.

Finally, while mothers are unfamiliar with some support services, the results of the survey provide a clear indication that fathers are even less aware of the services available to assist families with new children and infrequently use those with which they are familiar.

While it is not surprising that fathers turn to their partners when discussing parenting, depending on their female partners primarily for information may not be the best arrangement for many, especially if society wishes to increase fathers' involvement with children. However, barriers to fathers' use of the support services clearly exist, beginning with a lack of information directed specifically to fathers and male caregivers.

Acknowledgments

The Family Action Centre, University of Newcastle, received funding from Hunter Families First, NSW Department of Community Services, for this study. The authors acknowledge the contribution of several people who helped complete this project. We are indebted to our hard-working team: Michelle Gifford, Camilla McQualter, and Ken Bright. We are grateful to all the fathers and mothers who participated in the New Fathers Study.

Footnotes

The project reported here was the first part of a larger study, the second part of which surveyed service providers' experiences in regard to fathers accessing their services.

References

- Alexander B. Boot Camp for DADDY. Ladies Home Journal. 2000;117(7):102. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay L, Donovan J, Genovese A. Men's experiences during their partner's first pregnancy: A grounded theory analysis. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1996;13(3):12–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay L, Lupton D. The experiences of new fatherhood: A socio-cultural analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(4):1013–1020. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernadette-Shapiro S, Ehrensaft D, Shapiro J. L. Father participation in childcare and the development of empathy in sons: An empirical study. Family Therapy. 1996;23(2):77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Lumley J, Small R, Astbury J. 1994. Missing voices: The experiences of motherhood.. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman L. L. Expectant fathers and labor epidurals. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2000;25(3):133–138. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denner B. J. Marketing fatherhood: Man… being a father. 1998. Proceedings of the National Forum on Men and Family Relationships (pp. 147–153). Canberra, ACT: Family Relationships Branch, Department of Family and Community Services.

- Donovan J. The process of analysis during a grounded theory study of men during their partners' pregnancies. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1995;21(4):708–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21040708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar D, Glezer H. A man's place? Reconstructing family realities. Family Matters. 1992;31(April):36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle D, Doering S. The emergent father role. Sex Roles. 1988;18(34):119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R. 1995. Testosterone poisoning or terminal neglect? The men's health issue. Parliamentary Research Service Research Paper, No. 23 1995/96, Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher R, Silberberg S, Baxter R. 2001. Father's access to family-related services. A research report conducted by the Family Action Centre, The University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. Retrieved August 12, 2003, from www.newcastle.edu.au/centre/fac/efathers/papers/fathers-access-to-family-related-services.pdf] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway D, Svensson J, Clune L. What do men think of antenatal classes? International Journal of Childbirth Education. 1997;12(2):38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Fogg L, Tucker S. Efficacy of parent training for promoting positive parent-toddler relationships. Research in Nursing and Health. 1995;18:489–499. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren A, Kihlgren M, Forslin L, Norberg A. Swedish fathers' involvement in and experience of childbirth preparation and childbirth. Midwifery. 1999;15(1):6–15. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(99)90032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. J. How much parenting is a health responsibility? Medical Journal of Australia. 1990;153(11 & 12):696–698. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb126326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A. D, Brouse A. J. The experiences of new fathers during the first 3 weeks of life. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1991;16(3):293–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P. L. Laboring for relevance: Expectant and new fatherhood. Nursing Research. 1990;39(1):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauth D. G. Predictors of parental sense of competence for the couple during the transition to parenthood. Research into Nursing and Health. 2000;23:496–509. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200012)23:6<496::AID-NUR8>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroelinger C. D, Oths K. S. Partner support and pregnancy wantedness. Birth. 2000;27(2):112–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M. L. Fathers and child development: An introductory overview and guide. 1997. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of fathers in child development (3rd ed., pp. 1–18). New York: Wiley.

- May K. A. Three phases of father involvement in pregnancy. Nursing Research. 1982;31(6):337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride B. A. Parent education and support programs for fathers: Outcome effects on paternal involvement. Early Childhood Development and Care. 1991;67:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- McBride B. A, Rane T. R. 1996. Father/Male involvement in early childhood programs. Urbana, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED400123). [Google Scholar]

- Midmer D, Wilson L, Cummings S. A randomized, controlled trial of the influence of prenatal parenting education on postpartum anxiety and marital adjustment. Family Medicine. 1995;27(3):200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New South Wales Standing Committee on Social Issues. 1998. Working for children: Communities supporting families. Inquiry into parent education and support programs. Sydney, Australia: New South Wales Government. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols M. Paternal perspectives of the childbirth experience. Maternal-Child Nursing Journal. 1993;21(3):99–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord C. W. 1998. Father involvement in schools. Champaign, IL: ERIC Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED419632). [Google Scholar]

- Parr M. A new approach to parent education: The providers' viewpoint. Midwifery. 1988;6(3):160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Russell G. Shared parenting: A new childrearing trend. Early Child Development and Care. 1986;24:139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J. L. The expectant father. Psychology Today. 1987;21(1):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro J. L. When men are pregnant. 1995. In J. L. Shapiro, M. J. Diamond, & M. Greenberg (Eds.), Becoming a father (pp. 118–134). New York: Springer.

- Smith N. Men in antenatal classes: Teaching the “whole birth thing.”. Practising Midwife. 1999;2(1):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]