Abstract

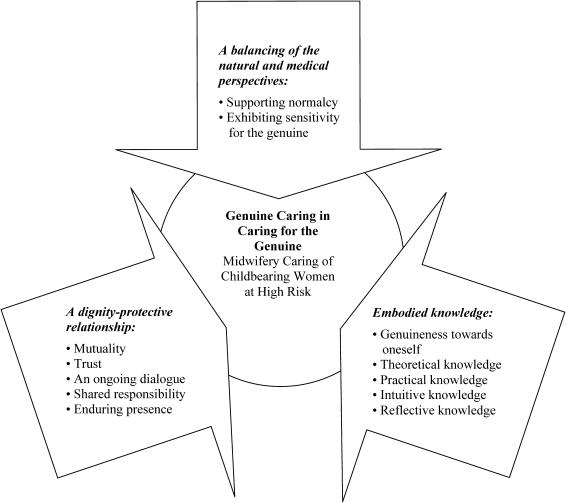

According to this paper's synthesis of research, three constituents of ideal midwifery care emerge. First, a dignity-protective action takes place in a midwife's caring relationship with a childbearing woman at high risk and includes mutuality, trust, ongoing dialogue, enduring presence, and shared responsibility. Secondly, the midwife's embodied knowledge is based on genuineness to oneself and consists of theoretical, practical, intuitive, and reflective knowledge. Finally, nurse-midwives have a special responsibility to balance the natural and medical perspectives in the care of childbearing women at high risk, especially by promoting the woman's inborn capacity to be a mother and to give birth in a natural manner. This midwifery model of care is labeled “Genuine Caring in Caring for the Genuine.” Here, the word genuine expresses the nature of midwifery care, as well as the nature of each pregnant woman being cared for as a unique individual.

Keywords: midwifery, caring, high-risk pregnancy, research synthesis

Introduction

The culture focusing on risk rather than the person has followed in the wake of modernity (Giddens, 1991) and influences the organization of health care, including maternity care. With maternity care's goal to reach optimal security and well-being, the childbearing woman is subjected to increased attention and care when the presence of risk factors or complications is apparent for herself or her child. Childbearing is defined here as the period during pregnancy, childbirth, and the early postpartum phase.

The proportion of childbearing women defined as being at high risk is constantly increasing. Today, conditions that previously did not allow women to go through pregnancy and childbirth with a healthy outcome are manageable, owing to medical developments including diagnostic and therapeutic procedures directed to both the woman and her fetus. New obstetric risk factors are constantly being identified. Additionally, interventions—especially of a technical nature—are continuously increasing. However, it is a question of doubt whether the greater frequency of high-risk women corresponds to a real increase. The reason is probably that modern maternity care is organised from a biomedical perspective, which is committed to detecting and treating diseases and complications, and deals with risks even when risks are relatively low. This perspective increases the frequency of interventions. It may also contribute to the fact that the definition of the concepts “normal pregnancy and delivery” has been narrowed over the years. In a Swedish study, only half of childbearing women were found to have a “normal” pregnancy and birth according to current definitions (Berglund & Lindmark, 2000). If normal childbirth should be defined as occurring without medical technique such as pain relief and pharmaceutical induction of labor, the proportion of normal childbirth may be less than 10% (Socialstyrelsen, 2001; World Health Organization, 1996).

Pregnant women labeled as high risk are exposed and vulnerable (Berg, Lundgren, & Lindmark, 2003). Emotionally, they are more anxious, worried, and ambivalent about their pregnancies (Gupton, Heaman, & Cheung, 2001; Hatmaker & Kemp, 1998; Mercer, 1990). Greater total risk is related to lower perceived self-efficacy, which has a negative effect on risk appraisal and emotions (Gray, 2001). Feelings of failure may be paramount (Jones, 1986), and the giving or sacrificing of oneself for the child is intensified. Instead of relying on themselves, the women try to diminish anxiety by turning over their bodies and their experiences to the external technological world. The need for support from others, especially from health-care professionals, is increased (Stainton, McNeil, & Harvey, 1992).

It has been suggested that the risk dimension in health science causes the practice of midwifery to be ever more narrowly circumscribed (Downe, 1996). Ever since Sweden's first midwifery regulation in 1711, Swedish midwives are expected to be responsible for normal childbearing women, while physicians are responsible for childbearing women at high risk (Lundqvist, 1940; Milton, 2001). Even in the care of women at risk, Swedish midwives, who are always registered nurses, have a responsible role. They are specialized in various risk-related fields where they are given delegated responsibility. However, it is important to gain more knowledge about the general, overall features and value of nurse-midwives' care of women at high risk and to investigate the basic motives and meanings in the contexts of midwifery care. Here, caring is defined as “good and ideal caring” and, thus, separated from uncaring, which is defined as a lack of caring or care that causes suffering (Eriksson, 1994, 2001; Halldórsdóttir, 1996). In order to promote ideal caring, the purpose of this study was to describe the essence of the midwifery model of care for women at high risk during childbearing.

Method

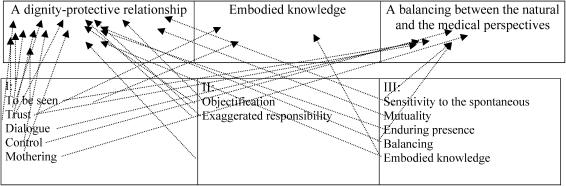

A research synthesis of three qualitative interview studies (of which the author served as primary investigator) was performed with the purpose of creating a general structure of the phenomenon known as “midwifery caring of childbearing women at high risk.” High risk is defined here as it was in the original three studies. All three previous studies are published. In the first study (I), a phenomenological study, 10 women with any kind of complicated childbirth were interviewed about their experience of childbirth (Berg & Dahlberg, 1998). In the second study (II), a hermeneutic phenomenological study, the researchers performed 44 interviews with 14 women who had diabetes type 1 during the course of their pregnancy (Berg & Honkasalo, 2000). The intent of this study was to search for the essential core of these women's experiences. In the third study (III), a phenomenological study, the researchers interviewed 10 midwives from four Swedish hospitals caring for pregnant women at high risk (Berg & Dahlberg, 2001). All three studies focused on the everyday world of experience (i.e., lifeworld experience) without prior application of any theoretical framework. (See Tables 1 and 2 for an overview of each study.) The method of data collection and analysis for each study is detailed elsewhere.

Table 1.

Demographics, Method, and High-Risk Conditions in the Included Studies

| Paper | Participants (Number, Age, Parity*) | Method | High-Risk Conditions** |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 10 Women 18–32 Years P: 8; M: 2 | Phenomenological Interview Study (10 interviews) | 2 Diabetes; 1 Renal Transplantation |

| 5 Emergency Cesarean Section | |||

| 2 Vacuum Extraction | |||

| 2 Perineal Suturing Under General Anaesthesia | |||

| 2 Manual Removal of Placenta | |||

| 7 Observed in the Intensive Care Unit | |||

| 3 Premature Babies | |||

| II | 14 Women 25–38 Years P: 8; M: 6 | Phenomenological Hermeneutical Interview Study (44 interviews) | 7 Diabetes, Duration 10–20 Years |

| 7 Diabetes, Duration >20 Years (of which 3 had severe vascular complications) | |||

| III | 10 Midwives 41–52 Years | Phenomenological Interview Study (10 interviews) | Work Experience: 9–29 Years |

| Work with Women at High Risk: 5–8 Years |

P = Primiparous; M = Multiparous

Every unique woman/child could have more than one complication.

I: Berg, M., & Dahlberg, K. (1998). A phenomenological study of women's experiences of complicated childbirth. Midwifery, 14, 23–29.

II: Berg, M., & Honkasalo, M.-L. (2000). Pregnancy and diabetes—A hermeneutic phenomenological study of women's experiences. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 21, 39–48.

III: Berg, M., & Dahlberg, K. (2001). Swedish midwives' care of women who are at high obstetric risk or who have obstetric complications. Midwifery, 17, 259–266.

Table 2.

Schematic Description of Study Phenomenon and Results in the Included Studies

| Study Phenomenon | Results—Constituents (Themes) | Results—Essence (Fundamental Nature) |

|---|---|---|

| I: Women's experience of an obstetrically complicated childbirth | • To be seen | Confirmation |

| • Trust | ||

| • Dialogue | ||

| • Control | ||

| • Mothering | ||

| II: Diabetes type I and pregnancy—Women's experiences | • Objectification: | The child makes demands |

| An unwell body—a risk | ||

| Loss of control | ||

| • Exaggerated responsibility: | ||

| Constant worry | ||

| Constantly under pressure | ||

| Constant self-blame | ||

| III: Midwives' care of women at high risk | • Sensitivity to the spontaneous | A struggle for the natural process |

| • Mutuality | ||

| • Enduring presence | ||

| • Balancing | ||

| • Embodied knowledge |

I: Berg, M., & Dahlberg, K. (1998). A phenomenological study of women's experiences of complicated childbirth. Midwifery, 14, 23–29.

II: Berg, M., & Honkasalo, M.-L. (2000). Pregnancy and diabetes—A hermeneutic phenomenological study of women's experiences. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 21, 39–48.

III: Berg, M., & Dahlberg, K. (2001). Swedish midwives' care of women who are at high obstetric risk or who have obstetric complications. Midwifery, 17, 259–266.

The philosophy of phenomenology stresses two factors:

The meaning of phenomena cannot be understood if they are not considered through human experiences.

Humans and their living conditions can never be completely understood if they are not studied as living wholes (Husserl, 1936/1970).

In the present analysis, the original texts from the three studies and their results (expressed as themes/constituents and quotations) were treated as a whole in the search for an essential structure of the phenomenon of ideal midwifery care of childbearing women at high risk. Both the women's and the midwives' perspectives were taken into account. The goal was to obtain openness; thus, the researcher accepted surprises and remained sensitive to the unexpected during the analysis (Dahlberg, Drew, & Nyström, 2001; Drew, 2001; Gadamer, 1995). By posing new questions to the results and the original texts, a new dialogue was created with the text. The questions were:

Which elements are essential in an ideal caring of women at high risk?

Which value possesses the caring that the women received?

What need of care is expressed?

All data that expressed something about the phenomenon were included. Even descriptions of uncaring were examined because, in their opposite nature, they clarified the feature of ideal midwifery care. Former constituents revealed in the earlier analysis of the original studies could be useful if they were representative for all studies/text. Finally, a general structure of the phenomenon was formulated.

Results

The resulting general structure from this new analysis has an essence (fundamental nature) labeled, “Genuine Caring in Caring for the Genuine.” It consists of three constituents:

a dignity-protective relationship,

embodied knowledge, and

a balancing of the natural and medical perspectives.

Here, the word genuine stands for authentic, true, natural, valid, ingenuous, and not-false attributes. It pertains to and expresses the nature of midwifery care, as well as the nature of each woman being cared for as a unique individual (see Table 3 and the Figure).

Table 3.

Relationship Between Themes in the Three Original Studies (I, II, and III) and the Synthesized Structure of the Model

| A Midwifery Model of Care for Childbearing Women at High Risk: Genuine Caring in Caring for the Genuine* |

|

Here, the word genuine stands for authentic, true, natural, valid, ingenuous, and not-false attributes. It expresses the nature of midwifery care, as well as the nature of each pregnant woman being cared for as a unique individual.

I: Berg, M., & Dahlberg, K. (1998). A phenomenological study of women's experiences of complicated childbirth. Midwifery, 14, 23–29.

II: Berg, M., & Honkasalo, M.-L. (2000). Pregnancy and diabetes—A hermeneutic phenomenological study of women's experiences. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 21, 39–48.

III: Berg, M., & Dahlberg, K. (2001). Swedish midwives' care of women who are at high obstetric risk or who have obstetric complications. Midwifery, 17, 259–266.

Overview: The General Structure for Midwifery Caring of Childbearing Women at High Risk.

The results of the present analysis are presented with quotations and their corresponding page numbers from the three published studies:

I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, W1–10 (Women 1 to 10)

II: Berg & Honkasalo, 2000, W1–14 (Women 1 to 14)

III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, M1–10 (Midwives 1 to 10).

Also, results of the present analysis include some quotations from the original text that were not published in the three previous studies. These quotations are referred to by the study number (I, II, or III), followed by the respondent's identification (woman or midwife).

A Dignity-Protective Relationship

Drawing from the present synthesis, an essential component of midwifery care for pregnant women at high risk is to protect the woman's dignity. The basis for this component is a caring relationship where each pregnant woman is treated as a unique person. Five overlapping elements are included: mutuality, trust, ongoing dialogue, shared responsibility, and enduring presence.

Mutuality

The caring relationship is expressed as a mutual process between the midwife and the pregnant woman. Mutuality is the opposite of one-sidedness. It means that both the midwife and the woman encounter each other in openness. Mutuality is opened and established between the midwife and the pregnant woman, not as a technique, but as a way of being:

A meeting cannot just be one-sided. It must be mutual. … The most important thing is to build a relationship, to build a bridge. Mutuality includes confirmation of the other: Make it plain that I see her (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 262, M5).

Mutuality may be expressed in a concrete manner; for example, by affirming a woman in pain during labor: “It was nice to get the confirmation, that you don't just imagine your pain” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 25, W8). Lack of confirmation, or disconfirmation, is an uncaring behavior which violates the woman's dignity: “I felt as if they found me troublesome” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 25, W2). Disconfirmation paves the way to feelings of stress, insecurity, disappointment, and ineffective pain management. It may also support feelings of failure and guilt.

Trust

Trust is also mutual. The midwife should trust the pregnant woman, her feelings, her capacity to give birth, and her ability as a mother-to-be. In order to perform caring, the midwife needs to feel that the woman trusts her, in both her professionalism and her attributes as a person. A pregnant woman who feels the midwife receives her dares, in return, to receive and trust the midwife's care and, thus, to relax:

Create reliability and security out of chaos.… I must establish a line of communication so that she can learn to trust and understand me. Feel safe with what I've got to offer and trust in it so that we can work together. That it is a mutual trust (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 262, M5).

I wasn't worried that anything would happen. They have to know their job. I have left myself in their hands (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 25, W8).

Ongoing dialogue

Dignity is protected through a real, ongoing dialogue. This is a way of showing respect for the pregnant woman. It is important for the woman to continuously be informed about what has happened and what is going to happen, even when the woman herself has difficulty in communicating: “So that one knew what to expect” (I, W7). Lack of dialogue expresses disrespect and, thus, violates dignity: “I know that I looked through a mist. I didn't understand. They talked beyond my control” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 26, W4). Dialogue unrelated to the woman's needs is a negative example: “They were talking about something unessential … rather, gossip concerning their salary or something else” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 26, W10).

Shared responsibility

Although pregnant women at high risk are in great need of expert care, they need to be involved in the process. The ideal condition occurs when responsibility is shared with the health-care providers, including the midwife. A midwife who takes over the situation by being too dominant may provoke feelings of objectification, another form of violating dignity: “It had to be done her way—just lie still—I was not allowed to say anything” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 25, W9). This behavior may pave the way for feelings of unreality, as for this woman who had an emergency cesarean section: “It was almost like being at the cinema. It wasn't me lying there” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 26, W2). Through shared responsibility, the woman may feel in control, even when health professionals guide the process. Another woman who went through an emergency cesarean section exemplifies this condition:

You are able to control the decision of leaving the control to other people. I am the thing that must be used to obtain what they want. You must leave your body. You don't look at yourself, but at the course of events. I saw somebody with a green dress. You look at an operating theatre…, you make an image for yourself (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 27, W8).

Enduring presence

Enduring presence is a necessary element in the dignity-protective caring of women at risk. The midwife should be present with the pregnant woman. It includes nearness and availability, in both an emotional and a physical sense. Availability in terms of time is also a part of this element: “I give her my time, show her that I have time for her. I stop and I sit down. … This is quality time that you are working with, as so many others are making demands upon you” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 262, M5).

Enduring presence also implies that all midwives who perform care for a certain pregnant woman form together as a collective. By coordinating with and complementing each other, a midwife is always at hand for the woman. The best situation for the woman is being treated by as few midwives as possible and striving for continuity by “minimizing the number of persons around every woman” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 262, M7). When the woman feels that the midwife is either emotionally or physically absent, she expresses violated dignity: “It was a real disappointment to feel alone. I found that this midwife just wasn't there” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 25, W4).

Embodied Knowledge

The second identified constituent of genuine care is embodied knowledge, the kind of knowledge the midwife uses as the most important tool in caring for at-risk women. The word embodied focuses on the fact that the knowledge is deep-rooted and integrated within the midwife. The midwife is her knowledge: “One learns new things all the time that sink in, leaving room for more learning. This is deep-rooted knowledge” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 263, M9). Midwives' knowledge is lived out through all their senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch, and the so-called sixth sense or intuition. Embodied knowledge consists of five integrated elements: genuineness towards oneself and theoretical, practical, intuitive, and reflective knowledge.

Genuineness towards oneself

For embodied knowledge to be a reality, the midwife's openness and genuineness towards herself are essential. This includes “acceptance of one's own personality and the courage to live it out without fearing to show one's own feelings” (III, M1). Caring for a woman with preeclampsia may exemplify this perspective. When the woman's symptoms become aggravated, midwives visit more often to observe her, measure blood pressure, and conduct blood tests: “She is worried anyway. … It is better to be forthright and explain what we are feeling, why, and what we are doing about it” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 262, M4). Here, the midwife's challenge is to promote security and trust while at the same time being honest by showing her own feelings.

Theoretical, practical, intuitive, and reflective knowledge

Sound theoretical knowledge about various complicated conditions and diseases that may interfere with childbearing is essential in the care of pregnant women at high risk. It gives midwives a feeling of security and safety in their professional role, a presupposition for guidance through the natural course of events, and an avoidance of “pathologization.” As one midwife noted, “We need more knowledge of all these complications, how they affect childbearing, in order to emphasize the normal” (III, M6).

Knowledge is also obtained through practical experience. There are no short cuts to gaining deep-rooted, embodied knowledge. The midwife must experience repeated, diverse situations with women to obtain knowledge rooted in practical experience. As one midwife reported, “Working as a midwife and meeting so many people and having these short, intensive meetings, and sometimes slightly longer relationships with patients—it's obvious that it provides me with experience of how to get to know a person” (III, M9).

There are no short cuts to gaining deep-rooted, embodied knowledge.

A more integrated level of embodied knowledge also exists, labeled intuitive knowledge, which can develop as professional experience increases. It is an excellent tool for understanding and determining a woman's condition and needs. Intuitive knowledge is often based on the impressions the midwife receives in the first encounter with the woman, such as a sense of worry or uneasiness or feelings that things are not quite right. It can also appear when “an unexpected course of events arises” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 263, M7). Courage is needed to act in accordance with intuition:

It has something to do with experience and sensitivity, which I also think has something to do with intuition—midwife-intuition, midwife-sense.… I do not think we should be afraid of trusting these feelings. We often feel things long before anyone else notices anything (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 263, M6).

Embodied knowledge presumes reflective knowledge—that is, to constantly reflect about care already given and about the actual caring situation. The work as a midwife is largely independent and lonely. The midwife is alone together with the pregnant woman and her family. These reflections are made both within oneself and with colleagues. Reflection with colleagues functions as guidance and as the basis for growing knowledge and increased security. As one midwife noted, “One needs to reflect on things with one's colleagues” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 263, M9).

A Balancing of the Natural and Medical Perspectives

Balancing the natural and medical perspectives is the third constituent of genuine caring in midwifery. Its elements are supporting normalcy and exhibiting sensitivity for the genuine.

Supporting normalcy

Pregnant women at risk want to be treated as normal. This is emphasized by women with diabetes mellitus who may have an aversion to every action and item of equipment that identifies them as special and at risk: “Simply that everything was so special-special” (II, W7). Midwives view childbirth as a normal life process and, therefore, use medical/technical support as tools for promoting the health and well-being of the mother and her child “…[t]o help the mother get through pregnancy and birth with as little sickness and complication as possible” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 263, M2).

A risk for “pathologization” or “the worst-scenario image” is embedded in the organization of care. The care of pregnant women at risk is based on the close collaboration between midwives and obstetricians. Sometimes, their different caring perspectives clash. A midwife's balancing act implies finding a level where both the natural and medical perspectives may exist side by side. It does not mean counteracting a special treatment; rather, it includes a struggle “to let nature take its course, to see childbirth and maternity time from the point of view of the normal” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 262, M6). Midwives are convinced that “every woman has an inborn strength that we support so that natural process is promoted” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 263, M8). Their challenge in the care of women at high risk is to treat childbearing as a genuine, normal process. With good embodied knowledge, midwives may even raise the level for normalcy:

I have reconsidered my views as to what sickness is and what health is. One would have thought that one would become fixated with the complicated, but it has been rather the opposite. I have raised the limit for what I consider as normal (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 263, M7).

Exhibiting sensitivity for the genuine

Midwifery caring includes a special, sensitive openness to the genuineness of every woman. Sensitivity for the genuine is also a dignity-protective action. It then becomes important to keep the pregnant woman in focus, to keep her in view: “She is not the complication in itself, but rather the person who has complications” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 261, M3). Also, “focus and see the woman more—not just the machines, tests, and everything surrounding her” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 261, M1). The genuine includes the process into motherhood that, for example, women with diabetes experience since early pregnancy: “You are pregnant from day one. It is such an intense pregnancy because you have your blood glucose levels and the well-being of the child in mind all the time” (II: Berg & Honkasalo, 2000, p. 41, W7).

Numerous examples demonstrate how midwives provide space for parenthood. In the care of a woman with advanced cervical cancer, this was a challenge: “They were both so happy because suddenly they were to be parents—it wasn't just all about cancer” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 261, M10). Physical closeness between mother and child is stimulated: “They came on to me with the incubator and took her [the baby] out of it. Then they put her on my tummy. And I thought it was lovely, yes, very nice and cozy. … I think it was the mother in me at once” (I: Berg & Dahlberg, 1998, p. 27, W9). Breastfeeding is supported even if the child has little chance of survival. When a baby is stillborn, the midwife can still confirm parenthood “so that they have a child they can mourn—to help parents meet their child” (III: Berg & Dahlberg, 2001, p. 261, M9).

Breastfeeding is supported even if the child has little chance of survival. When a baby is stillborn, the midwife can still confirm parenthood “so that they have a child they can mourn—to help parents meet their child.”

Self-accusations and a sense of inadequacy are frequent in pregnant women at risk. These conditions are exemplified by women with diabetes who struggle to reach normal blood glucose levels in order to give the growing child the best conditions for a healthy start in life: “If anything is wrong with the child or if something had shown up at the ultrasound, you would easily have blamed yourself a lot” (II: Berg & Honkasalo, 2000, p. 44, W7). Midwives' sensitivity for the genuine comprises affirmation of these feelings and, thus, empowers the woman's capacity as a mother.

Discussion

The lifeworld theory purports that, to understand a social reality, one must analyze the knowledge members have about that reality. The pretheoretical stance by use of the lifeworld theory (Dahlberg et al., 2001; Husserl, 1936/1970) and the synthesis of qualitative studies with pregnant women and midwives allowed the evolution of essential concepts in midwifery care. The results of the present analysis share similarities with central concepts in other midwifery theories and models (Kennedy, 2000; Lehrman, 1988; Swanson, 1991; Thompson, Oakley, Burke, Jay, & Conklin, 1989). However, the results are original in that the focus is on midwifery care for pregnant women at high risk.

Genuine caring focuses on the very nature of a midwife's way of being. To care for every woman in her genuineness is a dignity-protective action that, according to this research, seems to be the very motive of midwifery care for women at high risk and their families. It focuses on women's value as genuine humans and, specifically, as prospective mothers. The starting point and tool for this action is shown to be the caring relationship, which is frequently emphasised in other literature on caring (Eriksson, 2001; Paterson & Zderad, 1976/1988; Watson, 1988). Respect for the absolute dignity of the human being has been found to be the deepest ethical motive in caring (Edlund, 2002), including midwifery care (Kennedy, 2000; Thompson et al., 1989).

To care for every woman in her genuineness is a dignity-protective action that, according to this research, seems to be the very motive of midwifery care for women at high risk and their families.

The basis for mutuality between the midwife and a pregnant woman at risk is their openness to each other. According to the philosophers Lévinas (1982/1988) and Logstrup (1956), mutuality is a human responsibility—something originally abstract that becomes tangible when one sees the other's face (Lévinas, 1982/1988). Mutuality eliminates the space between the caregiver and patient (Buber, 1923/1970) and places them in a no-man's land where nobody predominates and both persons give and take (Lindström, 1987). To respond to another with such authenticity includes both vulnerability and risk (Bergum, 1992). Additionally, it paves the way for a close connection, which is necessary in a caring, empowering relationship (Halldórsdóttir, 1996, 2000; Travelbee, 1963).

Although the initiative and responsibility for this connection are placed upon the midwife, a caring relationship is not possible without the woman's willingness to face the midwife as a caring person. Confirmation is found to be part of mutuality. Bergum (1992) stated that the midwife and pregnant woman affirm each other when they collaborate as two living “I” beings. In order to support the human being's development into what he/she is meant to be (Eriksson, 2001), dignity-protective caring becomes a part of the ultimate purpose of caring and the basis for health.

The childbearing woman is foremost meant to be a mother. The findings of the present analysis emphasize that a pregnant woman at risk often feels inadequate as a mother-to-be and insufficient as a new mother. Therefore, the midwife's duty is to help strengthen the woman by confirming her needs and empowering her identity as a mother. The support for normalcy (Kennedy, 2000), including trust in the body (Bergum, 1997), is part of this process. An enormous, intrinsic power exists in motherhood, which midwives should promote even among women at risk (Berg & Honkasalo, 2000).

Kasén (2002) stated that a caring relationship can never be mutual because it is asymmetric in that the caretaker accepts greater responsibility, whereas the patient is seen as a suffering human being. However, mutuality does not necessarily mean an encounter on equal conditions. A mutual relationship may never be totally symmetric because it always includes a meeting of two unique persons. It is also important to stress that the pregnant woman, although at risk, is not described only as a “suffering” patient in the present findings, but particularly as a human being with genuine power.

Reciprocal trust is another essential element in the dignity-protective relationship. Women need to trust the midwife as a person and trust her professional competence (Halldórsdóttir, 1996; McCrea & Crute, 1991). In turn, the midwife should trust the woman. Reciprocal trust is a necessary component of a satisfying, effective health-care relationship (Thorne & Robinson, 1988).

Presence (that is, to be with the patient) has been shown to be central in caring (Gilje, 1992; Parse, 1981; Paterson & Zderad, 1976/1988; Rogers, 1981; Swanson, 1991; Watson, 1988), including midwifery caring (Berg, Lundgren, Hermansson, & Wahlberg, 1996; Coffman & Ray, 1999; Fleming, 1998; Hunter, 2002). Presence means closeness in a physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual sense and includes nearness in time, space, and amount (Paterson & Zderad, 1976/1988). In the sense of serving and being accessible, presence means to value the patient's dignity (Eriksson, Nordman, & Myllymäki, 1999). Demonstrating presence is eminently subjective and cannot be taught. The midwife learns presence when present to oneself. From this awareness of oneself, demonstrating presence to others can be learned (Donna, Haggerty, & Chase, 1997). In this synthesis of research, the element enduring presence constitutes another dimension of the essentiality (fundamental nature) of caring for high-risk women. As a collective, midwives provide an enduring presence for women. Perhaps their presence is of more importance in high-risk care, which is often long lasting and engages many caregivers. At the same time, midwives strive to diminish the number of medically intervening caregivers around the pregnant woman. Otherwise, the possibility for the midwife to be genuine and for the pregnant woman to trust is threatened.

The synthesis of this research illuminates the need for creating a genuine dialogue, including continuous information in order for the pregnant woman to feel a part of the process. The literature recognizes that women's sense of participation when giving birth has a great impact on their childbirth experience (Bramadat & Drieger 1993; Green, Coupland, & Kitzinger, 1990; Lavender, Walkinshaw, & Walton, 1999; Mackey, 1995; McIntosh, 1988; Seguin, Therrien, Champagne, & Larouche, 1989; Slade, MacPherson, Hume, & Maresh, 1993; Waldenström, Borg, Olsson, Sköld, & Wall, 1996). The present findings indicate that women at risk still want to maintain a sense of control, even when it is necessary to allow professionals to take charge. The element of shared responsibility focuses on this aspect. In other literature, shared responsibility is described as “shared control” and “entrusted control” (c.f., Corbin, 1987).

Trust and shared responsibility seem to be connected. Women who have sufficient trust and confidence in the health-care team may delegate to them the responsibility for performing the necessary action (Corbin, 1987). Maintaining control over one's body and health influences overall satisfaction (Loos & Julius, 1989; Stainton et al., 1992; Waldron & Asayama, 1985), whereas a perception of loss of control functions as a stressor in high-risk pregnancies and leads to feelings of helplessness, powerlessness, and a high level of dependency on expertise.

When uncaring behaviors (e.g., disconfirmation, distrust, and objectification) are present, pregnant women express negative feelings such as stress and poor self-confidence. These feelings are in accordance with other findings about uncaring behaviors (Johnston-Rieman, 1986) and within the domain of “suffering inflicted by care.” According to the literature, pregnant women's negative feelings are related to the caregiver's manner of acting or to deprivation of dignity, not being understood, not being taken seriously, and being reduced to a mere physical body (Eriksson, 1997; Halldórsdóttir, 1996). Midwives and other health-care providers should be encouraged to reflect on whether they protect women's dignity or contribute to an increased amount of suffering. Protecting women's dignity does not require more time; rather, it demands a consciousness of the importance of this particular dimension in care.

The present findings highlight that genuineness (i.e., a midwife's openness and knowledge of self) is of great importance both for ideal caring and for developing embodied knowledge. According to philosophy, all real human knowledge (e.g., understanding, memory, perception, and emotional and cognitive relations to the world) is embodied knowledge. In accordance with a philosophy of phenomenology, individuals live as subjects in and through their bodies (Heidegger, 1927/1998; Husserl, 1936/1970; Merleau-Ponty, 1945/1995). The present findings are largely similar to Benner's (1984) description of the development of nursing knowledge, although different words are used. Embodied knowledge is probably essential in caring, no matter what the profession. Because childbearing has risks, focusing on the embodied knowledge of complicated conditions and diseases seems extraordinarily important. Embodied knowledge may function as a tool for midwives to raise the limit for normalcy and protect the natural process during pregnancy and childbirth, including the growing, genuine, true aspect of motherhood, which is so easily downplayed in favor of a focus on the risk in itself. Thus, embodied knowledge may reduce the risk of pathologization. In this paper, natural means the genuine in the woman and the physical and emotional transition from woman to mother, which develops through her own power.

Supporting the normalcy of pregnancy and birth is also essential in the exemplary midwifery model developed by Kennedy (2000). The focus on the natural process of pregnancy and birth does not mean that reasonable and imperative medical treatment should be avoided. However, it may reduce the misuse and overuse of a variety of interventions, just as models of midwifery care for women at low obstetric risk have demonstrated significantly lower rates of interventions without compromising safety (Harvey, Jarell, Brant, Stainton, & Rach, 1996; Linder-Pelz, Webster, Martins, & Greenwell, 1990; Waldenström et al., 1996).

Midwives and physicians represent different perspectives. Midwives are more likely to view childbearing as a normal process, while obstetricians tend to view childbearing as a risk state (Rooks, 1999; Schuman & Marteau, 1993). Because a midwife's mode of working and philosophy is influenced by the health-care organization (Coyle, Hauck, Percival, & Kristjanson, 2001), the question is discerning how the risk focus in modern maternity care impacts midwives' mode of working. Olsson (2000) found that, even in antenatal care of women with “normal” processes, midwives sometimes become risk-oriented and begin to focus on the transition to motherhood as a feminine-risk project congruent with modern medical care instead of as a trustworthy, physical, emotional, existential, and social process.

Final Reflections and Practical Applications

In the present analysis, a general structure emerged with an essence labeled “Genuine Caring in Caring for the Genuine.” The structure consists of three constituents:

a dignity-protective relationship,

embodied knowledge, and

a balancing of the natural and medical perspectives.

This structure of care is based on a relationship characterized by respect for the high-risk pregnant woman in her uniqueness. It is performed through the midwife's use of her own deep-rooted knowledge expressed through her senses. It also consists of a constant struggle to maintain a balance between medically directed care and care that focuses on the natural process, particularly the woman's transition to motherhood.

The results of the present analysis contradict the statement that midwifery is marginalized in the care of women at high risk (Downe, 1996). Here, the conclusion demonstrates that the value of midwifery care does indeed exist in this context. However, in today's health culture, obstetric care is focused on risk, and an ongoing struggle continues for promoting the importance of the midwifery perspective. This challenge may not be limited to the Swedish context and is probably valid in all modern societies.

Midwifery is practiced at the point of intersection between “medical science” (which emphasizes that all births have a potential of pathology) and “traditionally-based knowledge” (which includes a natural view of childbearing) (Blåka-Sandvik, 1997). On the contrary, the findings described here indicate that the midwives' struggle is not for the legitimacy of their profession but, rather, for women's rights to remain in the natural process connected with pregnancy and childbirth. Balanced care of women at high risk is of utmost importance. On the one hand, it satisfies all women's medical needs and, on the other hand, promotes their belief in the inherent right to be mothers and to give birth in a natural manner.

Childbearing women at high risk live in an extremely vulnerable situation. It is crucial that midwifery and medical care exist on equal terms for the woman's sake. Perhaps a mix of the obstetric/medical and parent-oriented perspectives is preferable, including a confirming mode of collaboratively working together, as proposed by Hallgren, Kihlgren, and Norberg (1994). The basis for this collaboration is mutual respect and confidence, with both professions striving for the same goal to help the mother experience pregnancy and childbirth with as little sickness, complication, and intervention as possible (Berg & Dahlberg, 2001). Several years ago, Oakley (1989) posed an important question: “If technology is the obstetrician's weapon, what is a midwife's, anyway?” (p. 217). The present synthesis of research offers one answer: The midwife's weapon is genuine caring in caring for the genuine—that is, a dignity-protective, caring relationship based on embodied knowledge and a balance between the medical and natural perspectives.

The midwife's weapon is genuine caring in caring for the genuine—that is, a dignity-protective, caring relationship based on embodied knowledge and a balance between the medical and natural perspectives.

Editor's Note: Implications for Perinatal Educators

The development of this model of midwifery care for childbearing women at high risk can serve as a prototype for a similar development of a model of education for both high- and low-risk pregnant women. Models such as the one presented here, which are based on the lived experience of both childbearing women and care providers, can offer valuable assistance for developing evidence-based guidance in the field of childbirth education.

Further research is warranted and would serve as valuable resources for childbirth educators and expectant parents. Can the three themes presented here—dignity-protective actions, embodied knowledge, and the balancing of natural and medical perspectives—guide childbirth educators equally as well as midwives? Are there other themes that would also be useful? Continued investigation would certainly add to the field of childbirth education.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of a research project entitled “The Value of Caring,” at the Department for Health and Caring Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, Göteborg University, Sweden.

References

- Benner P. 1984. From novice to expert. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Dahlberg K. A phenomenological study of women's experiences of complicated childbirth. Midwifery. 1998;14:23–29. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(98)90111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Dahlberg K. Swedish midwives' care of women who are at high obstetric risk or who have obstetric complications. Midwifery. 2001;17:259–266. doi: 10.1054/midw.2001.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Honkasalo M.-L. Pregnancy and diabetes—A hermeneutic phenomenological study of women's experiences. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;21:39–48. doi: 10.3109/01674820009075607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Lundgren I, Hermansson E, Wahlberg V. Women's encounter with the midwife during childbirth. Midwifery. 1996;12(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(96)90033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M, Lundgren I, Lindmark G. Childbirth experience in women at high risk: Is it improved by use of a birth plan? Journal of Perinatal Education. 2003;12(2):1–15. doi: 10.1624/105812403X106784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund A, Lindmark G. Risk assessment at the end of pregnancy is a poor predictor for complications at delivery. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2000;79:853–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergum V. 1992, May 31–June 3. The dialectical approach to clinical judgement in nursing. Paper presented at the Third International Invitational Pedagogy Conference, University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Bergum V. 1997. A child on her mind. The experience of becoming a mother. London: Bergin & Garvey. [Google Scholar]

- Blåka-Sandvik G. 1997. Moderskap och födselarbeid (Motherhood and labour). Bergen Sandviken: Fagbokforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Bramadat I, Drieger M. Satisfaction with childbirth. Theories and methods of measurement. Birth. 1993;20:22–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1993.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buber M. 1970. I and thou (W. Kaufman, Trans.). New York: Scribner. (Original work published 1923) [Google Scholar]

- Coffman S, Ray M. A. Mutual intentionality: A theory of support processes in pregnant African-American women. Qualitative Health Research. 1999;9:479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J. M. Women's perceptions and management of a pregnancy complicated by chronic illness. Health Care for Women International. 1987;8:317–337. doi: 10.1080/07399338709515797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle K, Hauck Y, Percival P, Kristjanson L. Normality and collaboration: Mothers' perceptions of birth centre versus hospital care. Midwifery. 2001;17:182–193. doi: 10.1054/midw.2001.0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg K, Drew N, Nyström M. 2001. Reflective lifeworld research. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Donna M. E, Haggerty L. A, Chase S. K. Nursing presence: An existential exploration of the concept. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice. 1997;11:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downe S. Concepts of normality in maternity services: Applications and consequences. 1996. In L. Frith (Ed.), Ethics and midwifery (pp. 86–102). Oxford, England: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Drew N. Meaningfulness as an epistemologic concept for explicating the researcher's constitutive part in phenomenologic research. Advances in Nursing Science. 2001;23:16–31. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund M. 2002. Människans värdighet. Ett grundbegrepp inom vårdvetenskapen (Human dignity. A basic caring science concept). Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Åbo Akademi, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K. 1994. Den lidande människan (The suffering human). Stockholm, Sweden: Liber. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K. Understanding the world of the patient, the suffering human being: The new clinical paradigm from nursing to caring. Advanced Practice Nursing Quarterly. 1997;3:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K. Caring science in a new key. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2001;15:61–65. doi: 10.1177/089431840201500110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K, Nordman T, Myllymäki I. 1999. Den trojanska hästen. Evidensbaserat vårdande ur ett vårdvetenskapligt perspektiv (The Trojan horse. Evidence-based caring from a caring science perspective). Åbo, Finland: Institutionen för Vårdvetenskap, Helsingfors Universitetscentralsjukhus, Rapport 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming V. E. M. Women-with-midwives-with-women: A model of interdependence. Midwifery. 1998;14:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(98)90028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadamer H.-G. 1995. Truth and method (2nd ed., revised). New York: The Continuum Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. 1991. Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilje F. Being there: An analysis of the concept of presence. 1992. In D. A. Gant (Ed.), The presence of caring in nursing (pp. 53–67). New York: National League for Nursing. [PubMed]

- Gray B. A. 2001. Women's subjective appraisal of pregnancy risk and the effects of uncertainty, perceived control, coping and emotions on maternal attachment. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Coupland V, Kitzinger J. Expectations, experiences and psychological outcomes of childbirth. A prospective study of 825 women. Birth. 1990;17:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1990.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupton A, Heaman M, Cheung L. W.-K. Complicated and uncomplicated pregnancies: Women's perception of risk. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 2001;30:192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halldórsdóttir S. 1996. Caring and uncaring encounters in nursing and health care—Developing a theory. Medical dissertations No. 493, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Halldórsdóttir S. 2000, November 16–19. Empowering patients in their vulnerability or disempowering them. A keynote paper presented at the International Scientific Conference: Nursing in the New Millennium. 30th Anniversary Conference of the Faculty of Nursing, Medical University in Lublin, Poland. [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren A, Kihlgren M, Norberg A. A descriptive study of childbirth education provided by midwives in Sweden. Midwifery. 1994;10:215–224. doi: 10.1016/0266-6138(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey S, Jarell J, Brant R, Stainton C, Rach D. A randomized controlled trial of nurse-midwifery care. Birth. 1996;23(3):128–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1996.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatmaker D. D, Kemp V. H. Perception of threat and subjective well-being in low-risk and high-risk pregnant women. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 1998;12:1–10. doi: 10.1097/00005237-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger M. 1998. Being and time (J. Macquarried & E. Robinson, Trans.). Oxford, England: Blackwell. (Original work published 1927) [Google Scholar]

- Hunter L. P. Being with woman: A guiding concept for the care of laboring women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 2002;31:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husserl E. 1970. The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy (D. Carr, Trans). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. (Original work published 1936) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston-Rieman D. Noncaring and caring in the clinical setting: Patients' descriptions. Topics in Clinical Nursing. 1986;8:30–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. B. The high-risk pregnancy. 1986. In S. H. Johnson (Ed.), Nursing assessment and strategies for the family at risk (2nd ed.; pp. 11–128). Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- Kasén A. Den vårdande relationen (The caring relationship). 2002. Doctoral dissertation. Åbo, Finland: Åbo Akademi University Press, Finland.

- Kennedy H. P. A model of exemplary midwifery practice: Results of a Delphi study. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2000;45:4–19. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(99)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender T, Walkinshaw S. A, Walton I. A prospective study of women's views of factors contributing to a positive birth experience. Midwifery. 1999;15:40–46. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(99)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrman E. J. 1988. A theoretical framework for nurse-midwifery practice. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ. [Google Scholar]

- Lévinas E. 1988. Etik och oändlighet (Ethics and infinity). Stockholm, Sweden: Symposion. (Original work published 1982) [Google Scholar]

- Linder-Pelz S, Webster M. A, Martins J, Greenwell J. Obstetric risks and outcomes: Birth centre compared with conventional labour ward. Community Health Study. 1990;14(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1990.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindström U. Å. 1987. Psykiatrisk vårdlära (Psychiatric caring). Stockholm, Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksell. [Google Scholar]

- Logstrup K. E. 1956. Den etiske fordring (The ethical demand). Copenhagen, Denmark: Gyldendalske Boghandel Nordisk Forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Loos C, Julius L. The client's view of hospitalization during pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 1989;18:52–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1989.tb01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist B. Svenska barnmorskeväsendets historia (The history of Swedish midwifery). 1940. In B. Lundqvist (Ed.), Svenska barnmorskor (Swedish midwives) (pp. T41–45). Stockholm, Sweden: Svenska Yrkesförlaget.

- Mackey M. Women's evaluation of their childbirth performance. Maternal Child Nursing Journal. 1995;23:57–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea H, Crute V. Midwife/client relationship: Midwives' perspectives. Midwifery. 1991;7:183–192. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(05)80197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh J. Women's views of communication during labour and delivery. Midwifery. 1988;4:166–170. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(88)80072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer R. T. 1990. Parents at risk. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty M. 1995. Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.). London: Routledge. (Original work published 1945) [Google Scholar]

- Milton L. 2001. Folkhemmets barnmorskor. Den svenska barnmorskekårens professionalisering under mellan-och efterkrigsåren. (Midwives in the Folkhem. Professionalization of Swedish midwifery during the interwar and postwar period). Studia Historica Uppsaliensia 196. Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala Universitet. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley A. Who cares for women? Science versus love in midwifery today. Midwives Chronicles. 1989;102:214–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson P. 2000. Antenatal midwifery consultations. A qualitative study. Medical dissertation, New Series No. 643, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- Parse R. R. 1981. Man-living-health: A theory of nursing. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson J, Zderad L. 1988. Humanistic nursing. New York: National League for Nursing. (Original work published 1976) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers D. Science of unitary man. 1981. In G. Lasker (Ed.), A paradigm for nursing (pp. 1719–1722). New York: Pergamon Press.

- Rooks J. P. The midwifery model of care. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1999;44:370–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman A. N, Marteau T. M. Obstetricians' and midwives' contrasting perceptions of pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1993;11:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Seguin L, Therrien R, Champagne F, Larouche D. The components of women's satisfaction with maternity care. Birth. 1989;16:109–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1989.tb00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade P, MacPherson S. A, Hume A, Maresh M. Expectations, experiences and satisfaction with labour. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1993;32:469–483. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1993.tb01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socialstyrelsen (The National Board of Health and Welfare). 2001. Handläggning av normal förlossning (Normal birth—State of the art). Stockholm, Sweden: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Stainton M. C, McNeil D, Harvey S. Maternal tasks of uncertain motherhood. Maternal Child Nursing Journal. 1992;3:113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K. M. Empirical development of a middle range theory of caring. Nursing Research. 1991;40:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J, Oakley D, Burke M, Jay S, Conklin M. Theory building in nurse-midwifery: The care process. Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 1989;34:120–130. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(89)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. E, Robinson C. A. Reciprocal trust in health care relationship. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1988;13:782–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1988.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travelbee J. What do we mean by rapport? The American Journal of Nursing. 1963;63:70–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldenström U, Borg I. M, Olsson B, Sköld M, Wall S. The childbirth experience: A study of 295 new mothers. Birth. 1996;23:144–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1996.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron J, Asayama V. Stress, adaptation and coping in a maternal-fetal intensive care unit. Social Work Health Care. 1985;10:75–89. doi: 10.1300/J010v10n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. 1988. Nursing: Human science and human care: A theory of nursing. New York: National League for Nursing Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 1996, March 25–20. Care in normal birth. Report of the Technical Working Group Meeting on Normal Birth. Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]