Abstract

The ability of Cryptococcus neoformans to grow at the mammalian body temperature (37°C to 39°C) is a well-established virulence factor. Growth of C. neoformans at this physiological temperature requires calcineurin, a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase. When cytosolic calcium concentrations are low (∼50 to 100 nM), calcineurin is inactive and becomes active only when cytosolic calcium concentrations rise (∼1 to 10 μM) through the activation of calcium channels. In this study we analyzed the function of Cch1 in C. neoformans and found that Cch1 is a Ca2+-permeable channel that mediates calcium entry in C. neoformans. Analysis of the Cch1 protein sequence revealed differences in the voltage sensor (S4 regions), suggesting that Cch1 may have diminished voltage sensitivity or possibly an alternative gating mechanism. The inability of the cch1 mutant to grow under conditions of limited extracellular calcium concentrations ([Ca2+]extracellular, ∼100 nM) suggested that Cch1 was required for calcium uptake in low-calcium environments. These results are consistent with the role of ScCch1 in mediating high-affinity calcium uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Although the growth defect of the cch1 mutant under conditions of limited [Ca2+]extracellular (∼100 nM) became more severe with increasing temperature (25°C to 38.5°), this temperature sensitivity was not observed when the cch1 mutant was grown on rich medium ([Ca2+]extracellular, ∼0.140 mM). Accordingly, the cch1 mutant strain displayed only attenuated virulence when tested in the mouse inhalation model of cryptococcosis, further suggesting that C. neoformans may have a limited requirement for Cch1 and that this requirement appears to include ion stress tolerance.

Calcium (Ca2+) is an intracellular messenger whose universal role in controlling numerous cellular processes in eukaryotes relies on a versatile Ca2+ signaling network (reviewed herein and in reference 4). Within the network there is a gamut of signaling components that monitor Ca2+-mobilizing signals, mediate the movement of Ca2+ into the cytosol, and translate the Ca2+ signal into a cellular response (4). Because many of the key features of the Ca2+ signaling mechanisms are conserved throughout eukaryotic organisms, several signaling components such as Ca2+ channels, pumps, and transporters and calmodulin-regulated proteins are also present within fungal cells (49).

Calcineurin, a calmodulin target, is a serine/threonine-specific protein phosphatase whose activation occurs upon binding a Ca2+/calmodulin complex (1, 21, 27, 42). In the model pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans, calcineurin activity is essential for growth at the mammalian body temperature (38). This virulence trait is critical for pathogenesis, and consequently calcineurin mutants lacking either the catalytic or the regulatory subunit were avirulent in animal models of cryptococcosis (17, 28, 38). In Candida albicans calcineurin activity was essential for its survival in serum and tolerance to antifungal compounds (5, 43). In the nonpathogenic model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae calcineurin activity regulated stress-activated transcription, Ca2+ homeostasis, and morphogenesis (11, 18).

Calcium sensors like calmodulin monitor cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]cytosol) and translate a rise in [Ca2+]cytosol into a cellular response through the activation of Ca2+ binding proteins like calcineurin. The rapid and transient rise in [Ca2+]cytosol is specifically mediated by Ca2+-permeable channels that control the entry of external Ca2+ or the release of Ca2+ from internal stores (4). Upon the activation of Ca2+ channels, Ca2+ enters along its steep electrochemical potential gradient and is then rapidly removed from the cytosol by various pumps and transporters (4). Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediate Ca2+ entry into mammalian cells in response to membrane depolarization (8). Detailed electrophysiological analysis has revealed multiple types of Ca2+ currents that are primarily defined by different α1 subunits (8).

The structural topology of the Cch1 protein is most similar to the α1 subunit of a novel four-repeat protein (Rb21) related to voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (30). Despite attempts to express Rb21 in two expression systems (Xenopus laevis oocytes and tsA201 mammalian cells), channel currents were not measured. Consequently the channel kinetics of Rb21 are not known, but certain features in its amino acid sequence suggest that Rb21 may have unique gating properties (30). The channel kinetics of Cch1 also remain elusive since electrophysiological studies of Cch1 have not been reported. In S. cerevisiae, ScCch1 and ScMid1 have been proposed to form a high-affinity Ca2+ entry system based on identical phenotypic defects in strains lacking either ScCch1 or ScMid1, including reduced Ca2+ influx (36) and loss of viability after exposure to the mating pheromone (6, 16). That ScCch1 and ScMid1 associate with each other is supported by the observation that ScMid1 coimmunoprecipitates with ScCch1; however, how this interaction promotes channel activation and/or regulation is not known (6, 31, 32). Interestingly, ScMid1 appears to form a stretch-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel when expressed in COS7 and in CHO cells, suggesting that it may form a channel on its own and function independently of ScCch1 (25).

Activation of the ScCch1-ScMid1 complex in S. cerevisiae has been observed during pheromone treatment (23), mild heat shock (31, 50), cold stress (40), hypoosmotic shock (3), endoplasmic stress (6, 7), ionic stress (Li+, Na+, and Fe2+) (35, 37, 40), and cell wall and endoplasmic reticulum stress (6, 7, 31). In the fungal pathogen Candida glabrata, strains defective in CgCch1-CgMid1 function were more susceptible to fluconazole, an antifungal drug, and displayed a significant loss of viability upon prolonged fluconazole exposure, suggesting that the activity of the CgCch1-CgMid1 complex promoted survival under azole stress (26).

Far less is known about the function of the Cch1-Mid1 channel complex in C. neoformans and about its role in promoting virulence. Given the primary function of Ca2+-calcineurin-mediated signaling in controlling some key traits of C. neoformans that promote its survival during the infection process, the role of Cch1 within this signaling network is particularly interesting. The results presented here highlight a primary role of Cch1 in mediating calcium uptake in C. neoformans and promoting its survival in a low-calcium environment, similar to conditions that C. neoformans would face during intracellular growth within macrophages (4, 20). Our findings also raise the possibility that the gating of the Cch1 channel may be controlled by a mechanism other than voltage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

The C. neoformans strains used in this study were H99 (MATα, serotype A), H99 cch1::URA5 ura5 (MATα, serotype A), and H99 cch1::CCH1 ura5 (MATα, serotype A). C. neoformans strains H99 (serotype A, MATα) and H99r (spontaneous ura5 auxotroph derived from H99) were recovered from 15% glycerol stocks stored at −80°C prior to use in these experiments. Strains were maintained on YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose). Gene disruption transformants were selected on uracil dropout medium containing 1 M sorbitol (9, 10), and reconstituted strains were selected on 5-fluoroorotic acid medium. Dopamine agar and Christensen's agar were made as described previously (9, 10). The S. cerevisiae strains used in this study (cch1::TRP mid1::LEU) were derived from strain W303-1A and provided by K. W. Cunningham (32). All strains were grown in YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) or SD medium lacking uracil. Where indicated, a cell-impermeable version of BAPTA [1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N,N,-tetraacetic acid; cesium salt] was added at a final concentration of 1 mM (47) and sorbitol was added to a final concentration of 1 M. Unless otherwise noted, cells of C. neoformans were cultured in YPD at 30°C for 24 h.

Isolation of the CCH1 gene.

The amino acid sequence of the S. cerevisiae Cch1 protein was initially used to search the Duke IGSP Center for Applied Genomics and Technology strain H99 genomic DNA database (13), and a single 3,350-bp fragment having high homology was identified. This 3,350-bp fragment was amplified using PCR with primers cch1 and cch4 (cch1, TAGCTGGACGTTTCAGAAA; cch4, TGAGAAGTGGTGTGCGGTTT) and strain H99 genomic DNA as template, and the amplicon was subcloned to the plasmid. The genomic sequence was also subsequently used to search the Whitehead Institute Fungal Genome Initiative strain H99 genomic DNA database (48) to obtain the entire genomic locus. Both 5′- and 3′-RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) strategies were used to determine portions of the cDNA sequence, and bioinformatics approaches were also used to determine the putative coding regions and the putative amino acid sequence. The gene was named CCH1.

Disruption and reconstitution of CCH1.

The 3.35-kb genomic fragment was used to make a disruption construct by insertion of a 1,950-bp genomic fragment containing URA5 using an overlap PCR technique as described by Davidson et al. (12). The left and right arms of the deletion construct were amplified with the primer pairs cch1-cch2 and cch3-cch4, respectively (cch1, TAGCTGGACGTTTCAGAAA; cch2, GGTCGAGCAACTTCGCTCGGGTCCTATGCTCATTAC; cch3, CCACCTCCTGGAGGCAAGCGCATCAAGCGATCCATA; cch4, TGAGAAGTGGTGTGCGGTTT). The URA5 selectable marker was amplified with the primer pair cchura5 and cchura3 (cchura5, GTAATGAGCATAGGACCCGAGCGAAGTTGCTCGACC; cchura3, TATGGATCGCTTGATGCGCTTGCCTCCAGGAGGTGG). Amplicons of the left arm, right arm, and URA5 were gel purified, mixed together, and used to amplify the cch1::URA5 deletion construct using primers cch1 and cch4. The amplified deletion construct was gel purified and concentrated using a Speed-Vac concentrator and used to transform the ura5 auxotrophic strain H99R as described previously (9, 10). Transformants were selected on Ura dropout medium, and colony PCR was used to screen 384 colonies using primers cch5 and cch6 flanking the URA5 insertion (cch5, GTAATGAGCATAGGACCC; cch6, TATGGATCGCTTGATGCG). Disruption of the native CCH1 gene was confirmed using Southern blots probed with a labeled CCH1 fragment. A cch1 mutant strain having no extraneous insertions on Southern blotting was selected for further study. Reconstitution of the mutant strain to wild type was accomplished by transformation of the 3.35-kb genomic fragment and selection for reconstituted strains on 5-fluoroorotic acid medium. Reconstitution of the native CCH1 gene was done using PCR, and the reconstituted strains were restored to prototrophy by transformation using a genomic copy of URA5.

45Ca2+ uptake assay.

The 45Ca2+ uptake experiments were performed as described previously (32). Briefly, log-phase cultures of C. neoformans were collected by centrifugation, washed, and resuspended in fresh medium containing tracer amounts of 45CaCl2 (Amersham). The cells were incubated with 185 kBq of 45CaCl2 per ml (1.8 kBq/nmol) at 30°C for 0 to 5 min with intermittent mixing and then collected on Millipore filters (type HA, 0.45 μm). Filters were washed three times with 5 ml of cold 5 mM CaCl2 and processed for liquid scintillation counting. Specific activity of the medium (YPD contained 0.140 mM of total free Ca2+) was used to calculate total cell-associated Ca2+ (32).

Plate sensitivity assays.

Strains were incubated overnight at 30°C in YPD medium and grown to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.8 to 1.2). The cells were washed and diluted to 107 cells/ml, and 5 μl of a 10-fold serial dilution was spotted onto YPD plates containing 1 mM BAPTA, 1 M sorbitol, and/or 50 mM LiCl. To test the temperature sensitivity, plates were incubated at 25°C, 37°C, or 38.5°C for 48 h and photographed.

Murine model.

Cryptococci were used to infect 4- to 6-week-old female A/Jcr mice (NCI/Charles River Laboratories) by using nasal inhalation. Ten mice were infected with 5 × 104 yeast cells of the H99, cch1, and reconstituted strains in a volume of 50 μl via nasal inhalation as described previously (10). The mice were fed ad libitum and followed with twice-daily inspections. Mice that appeared moribund or in pain were sacrificed using CO2 inhalation. This protocol was approved by the Duke University Animal Use Committee. Survival data from the mouse experiments were analyzed by a Kruskal-Wallis test.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of CCH1 was submitted to GenBank with accession number DQ485411.

RESULTS

The predicted topology of Cch1 in C. neoformans was similar to the overall topology of Ca2+ voltage-gated channels in higher eukaryotes.

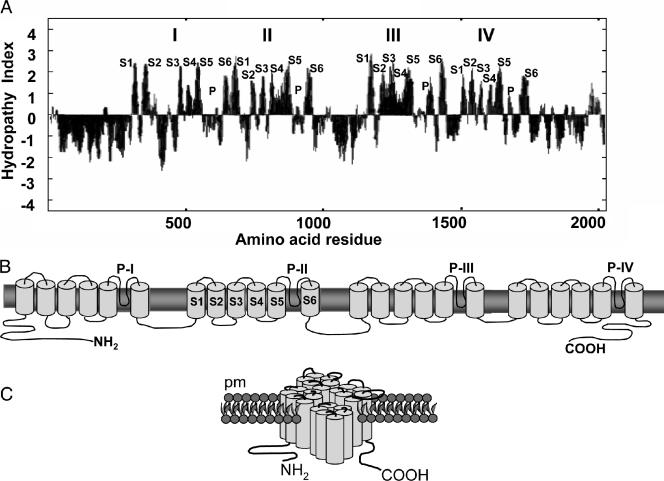

The CCH1 gene from C. neoformans contained 23 introns and 7,571 nucleotides, and the gene product was 2,091 amino acids. Hydropathy analysis was performed in order to predict the overall structural topology of the protein encoded by CCH1 in Cryptococcus neoformans (Fig. 1A) (29). The hydropathy plot revealed that Cch1 contained four repeated membrane domains (I, II, III, and IV), each consisting of six membrane-spanning regions that are connected by hydrophilic cytosolic regions. The six transmembrane regions (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, and S6) include pore loop segments between S5 and S6, indicated by smaller hydrophobic indices (P). The hydropathy profile agreed with the predicted topology determined by the TMpred program, which analyzed and predicted membrane-spanning regions and their orientations. Both profiles were used to create a schematic representation of the overall structure of Cch1 (Fig. 1B). The structural topology of Cch1 was similar to those reported for Ca2+ and Na+ channels in other eukaryotes where repeats I, II, III, and IV associate to create a pore within the center of the four repeats (Fig. 1C) (8, 39).

FIG. 1.

Predicted topology of Cch1 in C. neoformans. A. Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy index showing that Cch1 has four repeats (I, II, III, and IV) consisting of six membrane-spanning regions (S1 to S6) that are connected by hydrophilic cytosolic regions. B. Proposed two-dimensional schematic view of Cch1. The pore loops (P-I to P-IV) were located between S5 and S6 segments of each repeated unit as indicated by smaller hydrophobic indices. C. The four repeats, I, II, III, and IV, are predicted to associate and form the pore of Cch1 as predicted for voltage-gated Ca2+ channels of higher eukaryotes.

Cch1 was most similar to Cch1 in Ustilago maydis (45% identity and 61% similarity) and least similar to that in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (29% identity and 45% similarity) when the amino acids of each protein were compared. In higher eukaryotes, Cch1 was most closely related to a novel family of four-repeat-type voltage-gated ion channels (Rb21) similar to the α1 pore-forming subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (30). This recently identified channel is conserved in the genomes of nematodes, fruit flies, and mammals; however, the ion channel kinetics have not been characterized to date (30).

Although most of the sequence identity between Cch1 and other eukaryotic voltage-gated Ca2+ channels was present within regions that defined channel selectivity (pore region and P domain) and voltage sensing (S4), there were some striking differences within these regions in Cch1. The predicted S4 voltage sensor in each of the four repeats (I to IV) of known voltage-activated Ca2+ channels contains between five and eight positively charged amino acids (arginine [R] or lysine [K]) at approximately every third position with nonpolar and hydrophobic residues between them (8). This is true for all voltage-gated ion channels including Na+ and K+ channels (33). Interestingly, only the S4 segment in repeat III of Cch1 contained a positively charged region similar to that in voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, represented here by the L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel found in skeletal muscle of humans (Fig. 2A). The S4 region of repeats I, II, and IV displayed an atypical pattern with fewer arginines and lysines that were differentially spaced. This appeared to be present also in the novel four-repeat-type ion channel (Rb21) that was isolated from rat brains (30). This variation in Cch1 may reflect a diminished voltage sensitivity or perhaps unique gating properties.

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignments and analyses of Cch1, the L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (HsCa2+), and a novel four-repeat voltage-gated channel (Rb21) reveal differences in the voltage sensor and the pore region of Cch1. A. Only the S4 segment in repeat III of Cch1 contained a positively charged region (arginine [R] or lysine [K], highlighted) similar to the voltage sensor in HsCa2+ (L-type channel in human skeletal muscle). The amino acid sequence in the S4 segment of CnCch1 is similar to that of Rb21, the closest mammalian homologue of Cch1. B. Three of the four glutamic acid residues (E) present in the pore regions of domains II, III, and IV of the L-type Ca2+ are conserved in Cch1.

The pore loop regions between S5 and S6 form the ion selectivity filter of the α1 subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in higher eukaryotes (8). Four conserved glutamic acid residues in each of the four domains (I to IV) facilitate high-affinity divalent cation binding (41, 44). In Cch1 three of the four glutamic acid residues in the pore regions of domains II, III, and IV were conserved (Fig. 2B). These three residues are probably sufficient for promoting high-affinity calcium binding in Cch1 since evidence suggests that replacement of the glutamic acid residue in domain III of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels appeared to reduce Ca2+ binding the most (41, 44). In addition, no other high-affinity site exists within the pore of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (41, 44).

The cch1 mutant maintained most virulent traits.

cch1 mutant strains were constructed through targeted disruption. Out of 384 transformants screened with colony PCR, seven strains with disruption of the native gene were identified. All seven had apparently single integrations of the construct into the genome, and one was randomly selected for further analysis. Reconstitution of the strain back to wild type was done by homologous integration at the native locus using a fragment of the gene since we predicted that the size of the entire locus would prevent us from reconstituting the strain using ectopic integration. Phenotypic analyses of the cch1 and reconstituted strains demonstrated that, compared to wild type, there were no significant differences in capsule size in 5% CO2, urease activity, extracellular phospholipase activity, or melanin production on dopamine agar (data not shown).

Cch1 mediates calcium entry in C. neoformans.

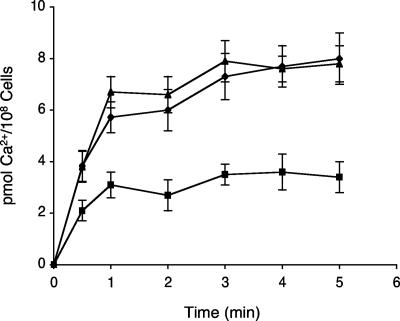

The biochemical activity of Cch1 was tested by measuring the initial rate of 45Ca2+ uptake in cells of C. neoformans. The initial rate of Ca2+ uptake was approximately 2.3-fold less in the cch1 mutant strain than in the wild-type and reconstituted strains, 2.8 pmol/108 cells/min for the cch1 mutant and 6.5 pmol/108 cells/min for the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). These results supported the role of Cch1 in mediating the entry of extracellular Ca2+ into C. neoformans.

FIG. 3.

Cch1 mediates Ca2+ entry in C. neoformans. Shown is 45Ca2+ uptake activity in cells from a log-phase culture of C. neoformans. Symbols: ▴, wild-type strain; ▪, cch1 mutant strain; ⧫, CCH1-reconstituted strain. The initial rate of Ca2+ uptake was ∼2.3-fold less in the cch1 mutant than in wild-type and reconstituted strains. The mean of four independent experiments is shown (± standard error).

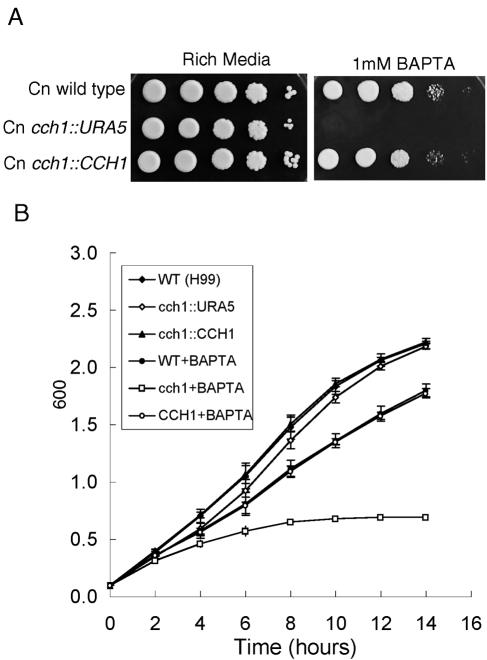

We examined whether Cch1 activity was required for growth of C. neoformans under conditions of low extracellular Ca2+ concentrations. A membrane-impermeable calcium-specific chelator (1 mM BAPTA) was added to rich medium (YPD) agar plates so that the final [Ca2+] available to cells was approximately 100 nM (47). The amount of calcium in the agar used here was approximately 30 μM (45). Much of this calcium is bound to agar and unavailable; therefore, the total free calcium in YPD agar is not significantly different from that in YPD alone, where the free calcium concentration was 0.140 mM (45). Growth of cch1 mutant cells was examined under both concentrations of free calcium (i.e., in the presence and absence of BAPTA) at 30°C in agar plate sensitivity assays and liquid cultures (Fig. 4). Under conditions of limited extracellular, free calcium (in the presence of BAPTA), the cch1 mutant displayed a severe growth defect in contrast to both wild-type cells and cch1::CCH1 reconstituted cells (Fig. 4A, right panel). However, the cch1 mutant was viable on YPD in the absence of BAPTA where the extracellular free calcium concentration was approximately 0.140 mM. Similarly, growth of cch1 mutant cells in liquid cultures was arrested only in the presence of 1 mM BAPTA where the rate of growth was reduced to approximately 2.5-fold by 14 h compared to wild-type and reconstituted strains (Fig. 4B). However, the cch1 mutant grew as well as wild-type and reconstituted strains in YPD alone (in the absence of BAPTA). Taken together, these results suggested that Cch1 was required for growth only under conditions of limited extracellular calcium concentrations, thus supporting the role of Cch1 in mediating calcium uptake in C. neoformans in low-calcium environments. These results are consistent with the role of ScCch1 in meditating high-affinity calcium uptake in S. cerevisiae (32).

FIG. 4.

Cch1 is required for growth under conditions of limited extracellular Ca2+. A. Tenfold serially diluted log-phase cultures of wild-type, cch1 mutant, and CCH1 reconstituted strains were spotted onto rich medium (YPD alone) ([Ca2+]free, ∼0.140 mM) plates or onto plates of YPD plus 1 mM BAPTA ([Ca2+]free, ∼100 nM) and incubated at 30°C for 2 days (n = 3). B. Log-phase cultures of each strain were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1, BAPTA was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and cultures were incubated at 30°C for 16 h. The optical density (600 nm) of each culture was recorded at the times shown. The mean of three independent experiments is shown (± standard error). WT, wild type.

The growth defect of the cch1 mutant was most severe at elevated temperatures only under conditions of limited extracellular concentrations of Ca2+.

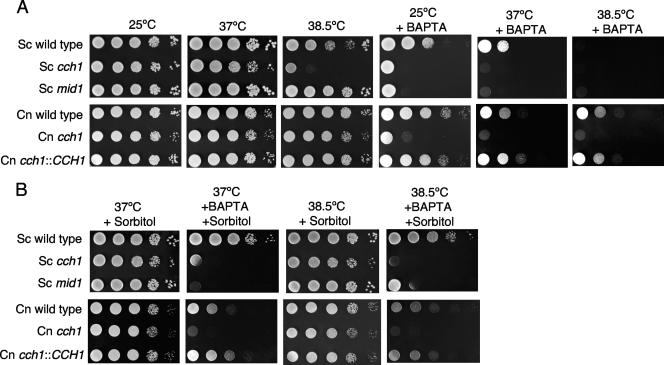

The growth of C. neoformans at the physiological temperature (37°C to 39°C) is a virulence trait that is controlled in part by a Ca2+-bound calmodulin via the activation of calcineurin (28). Since this process would require an increase in the [Ca2+]cytosol, we questioned whether Cch1 was required for high-temperature growth of C. neoformans. Tenfold serial dilutions of log-phase cultures were spotted onto YPD plates, where the free Ca2+ concentration was approximately 0.140 mM, and maintained at 25°C, 37°C, or 38.5°C. The cch1 mutant displayed only a very slight growth defect at 38.5°C compared to growth at 37°C or 25°C in the presence of 0.140 mM extracellular calcium, whereas wild-type strains and reconstituted strains grew equally well at all temperatures (Fig. 5A, lower panel). These results suggested that Cch1 activity was not required during high-temperature growth in the presence of a sufficient extracellular Ca2+ concentration. This may have been a consequence of a low-affinity calcium uptake system similar to what has been reported for S. cerevisiae (32). A similar low-affinity calcium uptake system in C. neoformans could mediate Ca2+ uptake under these conditions (i.e., high extracellular Ca2+ concentrations) and thereby satisfy the Ca2+ requirement during high-temperature growth.

FIG. 5.

C. neoformans and S. cerevisiae differ in their requirement for Cch1 during high-temperature growth and in regulating cell wall integrity. A. The growth defect of the C. neoformans cch1 mutant is more severe at higher temperatures only under conditions of low extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (in the presence of BAPTA). On YPD alone, the C. neoformans cch1 mutant does not display the temperature hypersensitivity of the Sccch1 mutant observed at 38.5°C on YPD alone. Tenfold serial dilutions of log-phase cultures of the indicated strains were spotted onto YPD plates, in the absence of BAPTA ([Ca2+]free, ∼0.140 mM) or in the presence of 1 mM BAPTA ([Ca2+]free, ∼100 nM), and incubated at 25°C, 37°C, or 38.5°C for 2 days (n = 3). B. The addition of 1 M sorbitol remedied the growth defect of the Sccch1 mutant at 38.5°C on YPD alone and of the S. cerevisiae wild-type strain on YPD plus 1 mM BAPTA. In contrast, sorbitol did not ameliorate the growth defect of the C. neoformans strains grown under similar conditions. Experiments were performed in the presence of 1 M sorbitol and 1 mM BAPTA as described above (n = 3).

Interestingly, under conditions of limited [Ca2+]extracellular (∼100 nM), the growth defect of the cch1 mutant became more severe with increasing temperature (25°C to 38.5°) (Fig. 5A, lower panel). This is consistent with the notion that Ca2+-dependent calcineurin activity is essential for high-temperature growth of C. neoformans (17, 38). Moreover the high-temperature sensitivity of the wild type and the reconstituted strains under similar conditions further suggested a strong requirement for sufficient extracellular Ca2+ during growth of C. neoformans at high temperatures (Fig. 5A, lower panel).

In contrast to the cch1 mutant, the Sccch1 mutant displayed a more pronounced growth defect at 38.5°C (Fig. 5A, upper panel) on YPD alone, suggesting a probable requirement for ScCch1 activity at elevated temperatures. This is consistent with other results that have shown an increased activity of the ScCch1-Mid1 complex during high-temperature growth of S. cerevisiae (31). Exposure of the Sccch1 mutant to elevated temperatures probably led to a cell wall defect, since the addition of an osmotic stabilizer such as 1 M sorbitol completely restored the growth of the Sccch1 mutant on YPD alone (Fig. 5B, upper panel). Under conditions of 38.5°C plus 1 mM BAPTA, the addition of 1 M sorbitol did not restore growth to the Sccch1 mutant strain as it did for cells grown at 38.5°C on YPD alone. In contrast sorbitol completely remedied the growth defect of the wild-type S. cerevisiae strain at 38.5°C in the presence of BAPTA. This was not the case for C. neoformans, as the addition of sorbitol did not ameliorate the growth defect of the C. neoformans strains grown under similar conditions (Fig. 5B, lower panel). These results would suggest that C. neoformans and S. cerevisiae differ in their requirement for Cch1 during high-temperature growth and in regulating cell wall integrity.

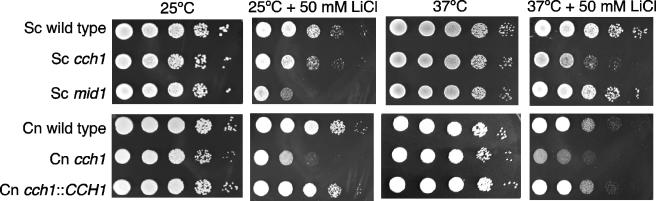

Cch1 plays a role in mediating ion stress tolerance in C. neoformans.

Because C. neoformans mutants that lack calcineurin are sensitive to Li+ cations (38), we asked whether Cch1 played a role in mediating ion stress tolerance. Tenfold serial dilutions of mid-log-phase cultures were spotted onto YPD plates with 50 mM LiCl and incubated at 25°C and 37°C. The cch1 mutant cells displayed a slight growth defect in the presence of Li+, and this defect was exacerbated at 37°C (Fig. 6, lower panel). Similarly, the Sccch1 mutant also displayed a growth defect in the presence of Li+ (Fig. 6, upper panel). These observations suggest that Cch1 plays a role in mediating Li+ stress tolerance in both organisms.

FIG. 6.

Cch1 plays similar roles in mediating ion stress tolerance in C. neoformans and S. cerevisiae. Both the cch1 and Sccch1 mutant strains were hypersensitive to the addition of 50 mM LiCl at 25°C and 37°C. The severe growth defect of the Scmid1 mutant observed at 25°C plus 50 mM LiCl was completely rescued at 37°C plus 50 mM LiCl. Tenfold serially diluted log-phase cultures of the indicated strains were spotted on rich medium plates (YPD) in the absence or presence of 50 mM LiCl and incubated at 25°C and 37°C for 2 days (n = 3).

Interestingly, the Scmid1 mutant displayed a severe growth defect at 25°C in the presence of Li+, more so than the Sccch1 mutant strain. However, the growth defect of the Scmid1 mutant in 50 mM Li+ at 25°C was almost completely ameliorated in 50 mM Li+ at 37°C (Fig. 6, upper panel). These findings are striking because they suggest that ScMid1 and ScCch1 may operate independently of each other in S. cerevisiae under certain conditions. This notion is further supported by the temperature hypersensitivity observed for the Sccch1 mutant at 38.5°C on YPD alone and not for the Scmid1 mutant under similar conditions (Fig. 5A, upper panel). This was in contrast to conditions of limited extracellular Ca2+ concentrations where both the Sccch1 and Scmid1 mutant strains showed similar growth defects, suggesting that ScCch1 and ScMid1 were both required for viability in low-calcium environments. This is consistent with previous results that have shown that the ScCch1-ScMid1 complex is required for high-affinity calcium uptake in S. cerevisiae (32). Whether Cch1 activity in C. neoformans is dependent on the function of the Mid1 homologue in C. neoformans under similar conditions is currently under investigation (L. Min and A. Gelli, unpublished data).

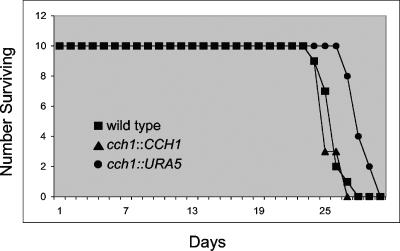

The cch1 mutant displayed attenuated virulence in the mouse inhalation model of cryptococcosis.

Since Ca2+-dependent calcineurin activity was required for C. neoformans virulence and our results strongly suggested that Ca2+ entry was mediated by Cch1, we questioned whether Cch1 played a role in mediating virulence. The role of Cch1 in the virulence of C. neoformans was tested in the mouse inhalation model of cryptococcosis (Fig. 7). The mean survival times for mice inoculated with wild-type and reconstituted strains were 24.9 days and 24.6 days (P = 0.397), respectively, suggesting no significant statistical difference between the virulence of the two strains. In contrast, mice inoculated with cch1 mutant cells survived longer, with a mean survival time of 27.4 days (P < 0.003) (Fig. 7). Although the cch1 mutant strain displayed attenuated virulence, it was not avirulent.

FIG. 7.

The cch1 mutant displayed attenuated virulence in the mouse inhalation model of cryptococcosis, but the cch1 strain was not avirulent. The mean survival times for mice inoculated with wild-type and reconstituted strains were 24.9 days and 24.6 days (P = 0.397), respectively. In contrast, mice inoculated with cch1 mutant cells survived longer, with a mean survival time of 27.4 days (P < 0.003).

DISCUSSION

The predicted topology of Cch1 in C. neoformans revealed an ion channel protein with some striking differences from the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in higher eukaryotes. Remarkably, Cch1 lacks the signature motif of the voltage sensor (present in other voltage-gated Ca2+, Na+, and K+ channels) in all but one of the S4 regions. In voltage-gated ion channels, the four S4 domains function independently of each other, each one performing mechanical work on the pore region such that the channel alternates between its conductive and nonconductive states (33). The periodicity of the positively charged regions of the S4 domains is essential for the screwlike movement of the S4 segments through the lipid membrane as they associate with the pore (14). Whether the atypical pattern of the S4 domains in Cch1 represents a Ca2+ channel that is weakly voltage gated or gated by an alternative mechanism such as the binding of a ligand is not clear. Conventional patch clamping experiments would be the only method by which these distinct features could be measured and understood in terms of Cch1 channel kinetics. These experiments are currently under way.

It may not be surprising that Cch1 might harbor some unique regulatory features, when one considers that four of the five subunits (α2, β, δ, and γ) that constitute voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in higher eukaryotes with the exception of the α1 subunit appear not to be present in fungi (8). Interestingly, the Mid1 homologue in C. neoformans (M. Liu and A. Gelli, unpublished results) and the ScMid1 appear to have a predicted topology similar to that of the γ subunit in higher eukaryotes (M. Liu and A. Gelli, unpublished results), but unlike the role of the γ subunit, ScMid1 has been shown to function as a stretch-activated calcium-permeable cation channel when expressed in COS7 cells and in CHO cells (25). These results are somewhat complicated by the fact that the distinction of whether ScMid1 is a stretch-activated channel itself or a subunit that activates an endogenous stretch-activated channel in COS7 and/or CHO cells has not been made. The bulk of evidence suggests that ScCch1 and ScMid1 function together as a high-affinity Ca2+ influx mechanism in S. cerevisiae, but the role of ScMid1 in ScCch1 function is not known. Interestingly, here we found that under conditions of high temperature both in the presence and in the absence of Li+ stress, ScCch1 appeared to operate independently of ScMid1 in S. cerevisiae. Conceivably, ScMid1 may have a limited and specific role in ScCch1 activity—perhaps akin to the down-regulatory role of the γ subunit in the activation kinetics of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in mammals (2, 24). This regulatory role of ScMid1 in ScCch1 function could be controlled by particular stress conditions of the cell. Whether Cch1 activity in C. neoformans is dependent on the function of the Mid1 homologue in C. neoformans is not known. In this case the phenotype of the C. neoformans mid1 mutant strain could be particularly telling.

Although mice infected with the C. neoformans cch1 mutant strain displayed improved survival, ultimately these mice succumbed to the infection. We questioned whether this was a reflection of a sudden increase in the available [Ca2+]free near the site of infection, in which case we would predict that Ca2+ could be entering cells by a low-affinity calcium uptake system in C. neoformans, similar to what has been reported for S. cerevisiae (32). Under these conditions the requirement for Cch1 in C. neoformans is bypassed and Ca2+-calcineurin-mediated signaling proceeds similarly to that in wild-type cells so that virulence is restored. This notion is supported by the fact that the cch1 mutant cells were viable only in the presence of sufficient [Ca2+]extracellular, suggesting that Cch1 was not required for calcium uptake under these conditions but it was required for Ca2+ uptake under conditions of low [Ca2+]extracellular (∼100 nM). The components of a low-affinity Ca2+ uptake system in C. neoformans have not been identified to date. Alternatively, virulence may have been restored to the cch1 mutant by the involvement of an endomembrane Ca2+ release channel in C. neoformans (M. Hong and A. Gelli, unpublished data).

High-temperature growth of S. cerevisiae leads to coactivation of the cell integrity mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway and Ca2+ signaling (31). The high-temperature growth defect of Sccch1 was rescued by the presence of an osmotic support (1 M sorbitol), suggesting that cells lacking Cch1 activity sustain cell wall defects. This is consistent with previously published reports for S. cerevisiae that support a role for ScCch1 in promoting calcineurin-mediated expression of FKS2, an alternative β-1,3-glucan synthase subunit, in response to growth at 39°C (19, 34, 50). However, under conditions of limited [Ca2+]extracellular the addition of sorbitol did not rescue the high-temperature growth defect of Sccch1. This suggested that cell wall synthesis might be completely impaired in cells that lack ScCch1, since high-affinity Ca2+ influx is solely dependent on ScCch1-ScMid1 activity. Accordingly, high-temperature growth under conditions of low [Ca2+]extracellular was restored by osmotic support only to S. cerevisiae cells that maintained ScCch1-ScMid1 activity. Interestingly, high-temperature growth of C. neoformans under similar conditions was not affected by the addition of an osmotic support. This may reflect differences in the requirement for Cch1 in regulating cell wall integrity in pathogenic and nonpathogenic fungi.

This study has demonstrated that survival of C. neoformans at the mammalian temperature is dependent on Cch1 activity only when C. neoformans is faced with limited [Ca2+]extracellular (∼100 nM). These concentrations correspond to the resting levels of [Ca2+]cytosolic in most cell types, including macrophages (4, 20). Alveolar macrophages represent the first line of defense during host infections and the site of dormant latent infections (15, 22). The survival of C. neoformans within macrophages promotes latent infections, which are subsequently reactivated in the event of a compromised immune system (15, 22). Macrophages may represent a low-calcium environment where survival of C. neoformans may depend on Cch1 activity. Indeed, survival of Histoplasma capsulatum within macrophages was reported to be calcium dependent (46). Blocking Cch1 activity should presumably prevent the survival of C. neoformans within macrophages. However, due to the rapid and transient nature of the rise in free [Ca2+]cytosol in signaling cells, the window of susceptibility may be relatively small. Nevertheless, whether Cch1 can be targeted for antifungal drug development will depend on the synthesis of pharmacological agents that could selectively block Cch1 with high affinity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eduardo Blumwald for assisting with 45Ca2+ uptake experiments and for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to Kyle W. Cunningham for sending us the Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains.

These studies were supported by an R01 grant, AI54477, awarded to A.G. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. G. M. Cox was supported by the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (AI39156).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aramburu, J., A. Rao, and C. B. Klee. 2000. Calcineurin: from structure to function. Curr. Top. Cell. Regul. 36:237-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arikkath, J., and K. P. Campbell. 2003. Auxiliary subunits: essential components of the voltage-gated calcium channel complex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13:298-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batiza, A. F., T. Schulz, and P. H. Masson. 1996. Yeast responds to hypotonic shock with a calcium pulse. J. Biol. Chem. 271:23357-23362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge, M. J., P. Lipp, and M. D. Bootman. 2000. The versatility and universality of calcium signaling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 1:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankenship, J. R., F. L. Wormley, M. K. Boyce, W. A. Schell, S. G. Filler, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2003. Calcineurin is essential for Candida albicans survival in serum and virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 2:422-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonilla, M., K. K. Nastase, and K. W. Cunningham. 2002. Essential role of calcineurin in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. EMBO J. 21:2343-2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonilla, M., and K. W. Cunningham. 2003. Mitogen-activated protein kinase stimulation of Ca2+ signaling is required for survival of endoplasmic reticulum stress in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4296-4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catterall, W. A. 2000. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16:521-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox, G. M., J. Mukherjee, G. T. Cole, A. Casadevall, and J. R. Perfect. 2000. Urease as a virulence factor in experimental cryptococcosis. Infect. Immun. 68:443-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox, G. M., H. C. McDade, S. C. A. Chen, S. C. Tucker, M. Gottfredsson, L. C. Wright, T. C. Sorrell, S. D. Leidich, A. Casadevall, M. Ghannoum, and J. R. Perfect. 2001. Extracellular phospholipase is a virulence factor in experimental cryptococcosis. Mol. Microbiol. 39:166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cyert, M. S. 2001. Genetic analysis of calmodulin and its targets in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:647-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson, R. C., J. R. Blankenship, P. R. Kraus, M. de Jesus Berrios, C. M. Hull, C. D'Souza, P. Wang, and J. Heitman. 2002. A PCR-based strategy to generate integrative targeting alleles with large regions of homology. Microbiology 148:2607-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duke IGSP Center for Applied Genomics and Technology. 2006. Published work and datasets. http://cgt.duke.edu.

- 14.Durrell, S. R., I. H. Shrivastava, and H. R. Guy. 2004. Models of the structure and voltage-gating mechanism of the shaker K+ channel. Biophys. J. 87:2116-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldmesser, M., S. Tucker, and A. Casadevall. 2001. Intracellular parasitism of macrophages by Cryptococcus neoformans. Trends Microbiol. 9:273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer, M., N. Schnell, J. Chattaway, P. Davies, G. Dixon, and D. Sanders. 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae CCH1 gene is involved in calcium influx and mating, FEBS Lett. 419:259-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox, D. S., M. C. Cruz, R. A. Sia, H. Ke, G. M. Cox, M. E. Cardenas, and J. Heitman. 2001. Calcineurin regulatory subunit is essential for virulence and mediates interactions with FKBP12-FK506 in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 39:835-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox, D. S., and J. Heitman. 2002. Good fungi gone bad: the corruption of calcineurin. Bioessays 24:894-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrett-Engele, P., B. Moilanen, and M. S. Cyert. 1995. Calcineurin, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, is essential in yeast mutants with cell integrity defects and in mutants that lack a functional vacuolar H+-ATPase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4103-4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Girotti, M., J. H. Evans, D. Burke, and C. C. Leslie. 2004. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 translocates to forming phagosomes during phagocytosis of zymosan in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 279:19113-19121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemenway, C. S., and J. Heitman. 1999. Calcineurin: structure, function, and inhibition. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 30:115-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Idnurm, A., Y. S. Bahn, K., Nielsen, X. Lin, J. A. Fraser, and J. Heitman. 2005. Deciphering the model pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:753-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iida, H., H. Nakamura, T. Ono, M. S. Okumura, and Y. Anraku. 1994. MID1, a novel Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene encoding a plasma membrane protein, is required for Ca2+ influx and mating. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:8259-8271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang, M. G., and K. P. Campbell. 2003. γ-Subunit of voltage-activated calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 278:21315-21318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanzaki, M., M. Nagasawa, I. Kojima, C. Sato, K. Naruse, M. Sokabe, and H. Iida. 1999. Molecular identification of a eukaryotic, stretch-activated nonselective cation channel. Science 285:882-886. (Erratum, 288:1347, 2000.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur, R., I. Castano, and B. P. Cormack. 2004. Functional genomic analysis of fluconazole susceptibility in the pathogenic yeast Candida glabrata: roles of calcium signaling and mitochondria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1600-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klee, C., H. Ren, and X. Wang. 1998. Regulation of the calmodulin-stimulated protein phosphatase, calcineurin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:13367-13370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraus, P. R., and J. Heitman. 2003. Coping with stress: calmodulin and calcineurin in model and pathogenic fungi. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311:1151-1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyte, J., and R. F. Doolittle. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157:105-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee, J. H., L. L. Cribbs, and E. Perez-Reyes. 1999. Cloning of a novel four repeat protein related to voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. FEBS Lett. 445:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin, D. E. 2005. Cell wall integrity signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69:262-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Locke, E. G., M. Bonilla, L. Liang, Y. Takita, and K. W. Cunningham. 2000. A homolog of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels stimulated by depletion of secretory Ca2+ in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6686-6694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long, S. B., E. B. Campbell, and R. MacKinnon. 2005. Voltage-sensor of Kv1.2: structural basis of electromechanical coupling. Science 309:903-908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazur, P., N. Morin, W. Baginsky, M. el-Sherbeini, J. A. Clemens, J. B. Nielsen, and F. Foor. 1995. Differential expression and function of two homologous subunits of yeast 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5671-5681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendoza, I., F. Rubio, A. Rodriguez-Navarro, and J. M. Pardo. 1994. The protein phosphatase calcineurin is essential for NaCl tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 269:8792-8796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller, E. M., E. G. Locke, and K. W. Cunningham. 2001. Differential regulation of two Ca2+ influx systems by pheromone signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 159:1527-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura, T., Y. Liu, D. Hirata, H. Namba, S. Harada, T. Hirokawa, and T. Miyakawa. 1993. Protein phosphatase type 2B (calcineurin)-mediated, FK506-sensitive regulation of intracellular ions in yeast is an important determinant for adaptation to high salt stress conditions. EMBO J. 12:4063-4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Odom, A., S. Muir, E. Lim, D. L. Toffaletti, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1997. Calcineurin is required for virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO J. 16:2576-2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paidhungal, M., and S. Garrett. 1997. A homologue of mammalian voltage-gated calcium channels mediates yeast pheromone-stimulated calcium uptake and exacerbates the cdc1(Ts) growth defect. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6339-6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peiter, E., M. Fischer, K. Sidaway, S. K. Roberts, and D. Sanders. 2005. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ca2+ channel Cch1pmid1p is essential for tolerance to cold stress and ion toxicity. FEBS Lett. 579:5697-5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson, B. Z., and W. A. Catteral. 1995. Calcium binding in the pore of L-type calcium channels modulates high affinity dihydropyridine binding. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18201-18204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rusnak, F., and P. Mertz. 2000. Calcineurin: form and function. Physiol. Rev. 80:1483-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, O. Marchetti, J. Entenza, and J. Bille. 2003. Calcineurin A of Candida albicans: involvement in antifungal tolerance, cell morphogenesis and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 48:959-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sather, W. A., J. Yang, and R. W. Tsien. 1994. Structural basis of ion channel permeation and selectivity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 4:313-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scholten, H. J., and R. L. M. Pierik. 1998. Agar as a gelling agent: chemical and physical analysis. Plant Cell Rep. 17:230-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sebghati, T. S., J. T. Engle, and W. E. Goldman. 2000. Intracellular parasitism by Histoplasma capsulatum: fungal virulence and calcium dependence. Science 290:1368-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsien, R. Y. 1980. New calcium indicators and buffers with high selectivity against magnesium and protons: design, synthesis and properties of prototype structures. Biochemistry 19:2396-2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitehead Institute Fungal Genome Initiative. 2005. Strain H99 genomic DNA database. http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/fgi/.

- 49.Zelter, A., M. Bencina, B. J. Bowman, O. Yarden, and N. D. Read. 2004. A comparative genomic analysis of the calcium signaling machinery in Neurospora crassa, Magnaporthe grisea, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:827-841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao, C., U. S. Jung, P. Garrett-Engele, T. Roe, M. S. Cyert, and D. E. Levin. 1998. Temperature-induced expression of yeast FKS2 is under the dual control of protein kinase C and calcineurin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:1013-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]