Abstract

When starved, the amoebae of Dictyostelium discoideum initiate a developmental process that results in the formation of fruiting bodies in which stalks support balls of spores. The nutrients and energy necessary for development are provided by autophagy. Atg1 is a protein kinase that regulates the induction of autophagy in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In addition to a conserved kinase domain, Dictyostelium Atg1 has a C-terminal region that has significant homology to the Caenorhabditis elegans and mammalian Atg1 homologues but not to the budding yeast Atg1. We investigated the function of the kinase and conserved C-terminal domains of D. discoideum Atg1 (DdAtg1) and showed that these domains are essential for autophagy and development. Kinase-negative DdAtg1 acts in a dominant-negative fashion, resulting in a mutant phenotype when expressed in the wild-type cells. Green fluorescent protein-tagged kinase-negative DdAtg1 colocalizes with red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged DdAtg8, a marker of preautophagosomal structures and autophagosomes. The conserved C-terminal region is essential for localization of kinase-negative DdAtg1 to autophagosomes labeled with RFP-tagged Dictyostelium Atg8. The dominant-negative effect of the kinase-defective mutant also depends on the C-terminal domain. In cells expressing dominant-negative DdAtg1, autophagosomes are formed and accumulate but seem not to be functional. By using a temperature-sensitive DdAtg1, we showed that DdAtg1 is required throughout development; development halts when the cells are shifted to the restrictive temperature, but resumes when cells are returned to the permissive temperature.

Dictyostelium discoideum amoebae have an elaborate program of development that begins with the aggregation of many thousands of amoebae by chemotaxis, followed by the formation of a mound of adhering cells. The mound transforms into a motile slug, which forms a fruiting body consisting of a spore mass on a thin stalk (16). Development occurs only during starvation, and therefore there must be turnover of macromolecules to provide energy and chemical constituents to the developing cells (40).

In the face of starvation most eukaryotic cells induce a process of self-digestion called macroautophagy (hereafter, autophagy). Dictyostelium amoebae starving in a nitrogen-free medium survive with near 100% viability for 2 weeks (26, 28). Their survival in the nitrogen-free medium depends on the process of autophagy. The events of autophagy begin with a preautophagosomal structure that forms a double membrane autophagosome, which envelops cytoplasm and organelles. These autophagosomes become digestive vacuoles by fusion with a hydrolase-containing vacuole or lysosomes.

By mutating the genes that code for Dictyostelium homologues of the budding yeast ATG1, ATG5, ATG6, ATG7, and ATG8, we have shown that autophagy is essential for development and is probably coordinated with it (26, 28). A previously identified Dictyostelium gene called tipD is the homologue of Atg16L, the mammalian homologue of ATG16 (23, 33). Dictyostelium autophagy mutants die in nitrogen-free medium much earlier than wild-type cells. They do not progress beyond early stages of development, although the development of some mutants can be partially rescued by exogenous amino acids (G. Otto, unpublished observations). Starving autophagy mutants do not degrade their cytoplasmic contents, so that by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) they are full of organelles and cytoplasmic contents, while the wild-type cells have depleted cytoplasm (see below). In addition, autophagy mutants and parental cells that have been starved display different densities after Percoll gradient centrifugation (T. Tekinay, unpublished observations). Autophagy mutants are strictly cell autonomous, as wild-type cells in a chimera with autophagy mutant cells do not rescue their development.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Atg1 interacts with several other proteins including Atg13, Atg17, Vac8, and Atg11 (8, 14, 32). Atg13 is hyperphosphorylated during growth by the Tor (target of rapamycin) kinase, preventing its association with Atg1 (1, 14). Autophagy is therefore blocked, and the cytoplasm-to-vacuole transport (CVT) pathway is induced. When cells starve, Tor is inactivated, and Atg13 becomes hypophosphorylated, increasing its interaction with Atg1 and initiating autophagy. The CVT pathway is not known to occur in Dictyostelium or other organisms. Although Dictyostelium possesses orthologues of most known autophagy genes, it lacks recognizable ATG13 and ATG17 coding sequences, as do other higher organisms except plants. This difference led us to ask whether Atg1 performs the same role in Dictyostelium as it does in S. cerevisiae.

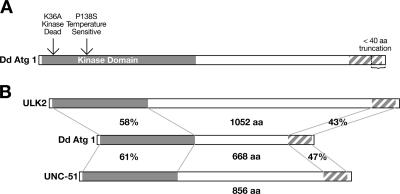

The D. discoideum Atg1 (DdAtg1) kinase domain (266 amino acids) shares significant sequence homology with Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-51 (Fig. 1B). There is also homology at the 122-amino-acid C-terminal region. The unc-51 mutant worms are paralyzed, egg-laying defective, and dumpy and have defects in axonal elongation (25). It was shown that UNC-51 is required for autophagy during dauer formation in C. elegans (22), although there is no direct evidence that autophagy is essential for axonal elongation. The mouse and human genomes have two copies of Atg1 homologues called UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2 (42, 41, 18). The C-terminal homology of DdAtg1 with UNC-51 is also found with mouse and human ULK2. Dominant-negative versions of both mouse homologues of ULK1 and ULK2 inhibit neurite expansion of primary granule neurons in vitro, suggesting that ULK proteins have a role in axon elongation like the C. elegans UNC-51 (39), but the involvement of the ULK proteins in autophagy is not established.

FIG. 1.

DdAtg1 is a serine/threonine kinase with a conserved C-terminal domain. (A) The kinase domain and a conserved 122-amino-acid C-terminal domain of DdAtg1 are shown. A plasmid expressing truncated protein lacking the C-terminal 40 residues was also constructed. The missing region in the truncation mutant is indicated by an arrow. Also shown are the positions of mutations of lysine 36 to alanine and proline 138 to serine that result in kinase-negative and temperature-sensitive DdAtg1 constructs, respectively. (B) The DdAtg1 kinase domain and C-terminal region are homologous to the C. elegans UNC-51, mouse ULK2, and human ULK2 proteins. Percent similarities are shown.

Abeliovich and colleagues suggest that the kinase activity of Atg1 is necessary for CVT but not for autophagy, where Atg1 may have a structural role (2). Kamada and colleagues proposed that the kinase activity is necessary for Atg1 function in autophagy and showed that the kinase activity is induced after starvation by using a kinase-negative mutant of the Atg1 protein (14). Recently, Kabeya and colleagues investigated the importance of the kinase activity of Atg1. They concluded that the kinase activity of Atg1 is essential for autophagy (12). Several studies suggest a role for Atg1 in late stages of autophagy. Suzuki and colleagues showed that Atg1 is involved in a late stage of autophagosome formation (36). In a recent study, Atg1 and its binding partners were found to be in an epistatic relationship with other ATG genes. Atg1 acts at later stages for localization of Atg8 (37). Atg1 is also important for retrieval of Atg9 and Atg23 from the site of autophagosome biogenesis, the preautophagosomal structure (PAS), and mitochondria (29, 30). ATG9, which encodes an integral membrane protein involved in autophagy, is present in Dictyostelium; but a homologue of ATG23, which is required for the CVT pathway, has not been identified in the completed Dictyostelium genome.

The absence of Atg1-associated proteins and the apparent lack of the CVT pathway in Dictyostelium led us to ask whether DdAtg1 functions to initiate autophagy and whether the kinase activity and the conserved C-terminal region are required for DdAtg1 function. To address these questions, we examined the effects of expressing kinase-negative and truncated DdAtg1 proteins in parental and atg1 mutant cells. We find that the kinase activity of DdAtg1 is required for autophagy in Dictyostelium and that the kinase-negative DdAtg1 acts in a dominant-negative way when expressed in wild-type cells, blocking autophagy and development. The atg1-null and dominant-negative strains can form autophagosomes, but their maturation appears to be blocked, leaving engulfed material intact in a large vesicle that is surrounded by numerous smaller vesicles. The C-terminal domain of DdAtg1 is also essential for DdAtg1 function and the dominant-negative effects of the kinase-negative protein. Finally, we used a temperature-sensitive DdAtg1 to show that when DdAtg1 activity is blocked, development stops quickly but reversibly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

All strains were derived from the uracil auxotroph DH1 and were grown in HL5 medium or in minimal medium (FM) with or without amino acids as previously described (26). Amoebae were also grown on lawns of Klebsiella pneumoniae on SM plates at 22°C (35). Development on Millipore filters has been described previously (35). All strains were reisolated from frozen stocks every 4 to 6 weeks. Temperature-sensitive variants of ATG1 tend to revert or be suppressed and must be recovered from original stocks.

Growth and survival studies.

For growth, cells were suspended in 25 ml of FM at 105/ml. The number of cells was counted with a hemocytometer every 24 h. To measure survival during starvation, growing cells were suspended in 10 ml of FM without amino acids at 105/ml and shaken at 120 rpm at 22°C. At the time points defined in the legend to Fig. 4, 10 μl of the culture or appropriate dilutions were plated on SM plates in association with K. pneumoniae, and the number of plaques that appeared after several days was counted.

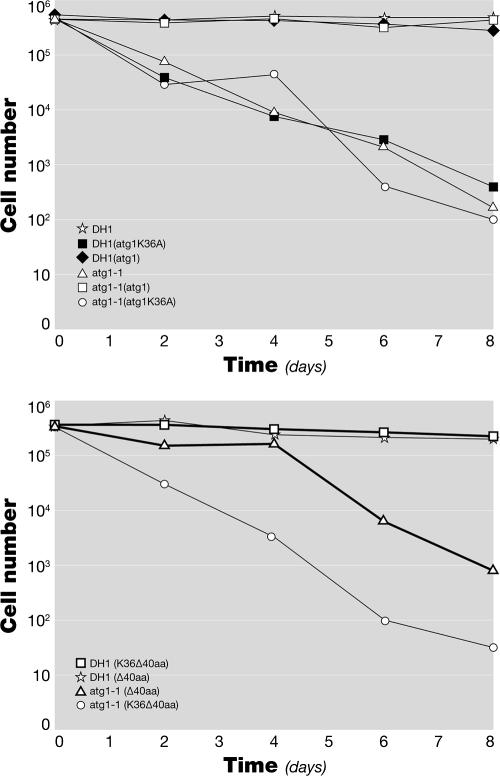

FIG. 4.

The dominant-negative DdAtg1K36A does not rescue the viability defect of the atg1-1 mutant during nitrogen starvation. Growing cells were suspended at 105/ml in 10 ml of FM without amino acids. Viability was determined every 2 days by a colony-forming assay. (A) Cells expressing DdAtg1 and DdAtg1K36A in DH1 and atg1-null backgrounds. DdAtg1K36A does not rescue the survival defect of atg1-1, and DdAtg1K36A acts as dominant negative in the DH1 background. (B) Cells expressing DdAtg1Δ40 and DdAtg1K36AΔ40 in DH1 and atg1-null backgrounds. Both DdAtg1Δ40- and DdAtg1K36AΔ40-expressing constructs are unable to rescue the survival defect of atg1-1, but DdAtg1K36AΔ-40 does not act as dominant negative. aa, amino acids.

Creation of mutant constructs.

To create a kinase-negative Atg1, the conserved lysine, K36, was mutated to serine by site-directed mutagenesis using a Stratagene Quikchange kit. The primers used were GAACCCTTTGCCATAGCGGTTGTCGATGTTTGTAGATTAGCG and CGCTAATCTACAAACATCGACAACCGCTATGGCAAAGGGTTC. The same strategy was used to mutate P138 into S to prepare a temperature-sensitive DdAtg1. The primers used were GATTGTTCATAGGGATTTAAAATCACAAAATTTATTATTAAGTG and CACTTAATAATAAATTTTGTGATTTTAAATCCCTATGAACAATC.

DdAtg1 lacking the C-terminal 40 residues (DdAtg1Δ40) was amplified by PCR using the primers AAACGAGTAGGAGATTATATTTT and GGTCATCAGAATCAATTAC. The truncated protein containing only the kinase domain was amplified by the primers GAAACGAGTAGGAGATTATATTTT and CCATTTATGATTAAAGAAATCTTCC.

Fusion constructs.

All gene constructs were made in mRFPmars (where RFP is red fluorescent protein), pDXA, or pTX vectors, which contain the constitutively active actin15 promoter (19) (7, 20). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged atg1 and atg carrying the mutation K36A (atg1K36A) were prepared by ligating SacI-digested atg1 and atg1K36A with SacI-digested pDXA-HC. GFP-Atg1Δ40- and GFP-DdAtg1K36AΔ40-expressing constructs were prepared by ligating BglII fragments containing GFP and the 5′ end of atg1/atg1K36A with a BglII fragment carrying the 3′ end of DdAtg1Δ40/DdAtg1K36AΔ40 in the pDXA-HC plasmid.

GST-DdAtg1 and GST-DdAtg1K36A were made by ligating SacI-digested atg1 and atg1K36A with SacI-digested pDXA-HC-GST (where GST is glutathione transferase). pDXA-HC-GST was made by ligating the GST sequence amplified from pGEX1λT (Pharmacia) with pDXA-HC, by using Kpn1 and SacI sites. The primers for the amplification of GST were CCGGTACCATGTCCCCTATACTAGGTTA and CCGAGCTCGGATCCACGCGGAACCAG.

GST-tagged atg1Δ40 and atg1 kinase-domain-only constructs were prepared by ligating EcoRI-digested pDXL-HC plasmid with EcoRI-digested atg1Δ40 and atg1 kinase-domain-only sequences. atg1 sequences were prepared by inserting the PCR products described above into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). pDXL-HC was prepared by inserting a linker region containing an EcoRI site from PstI-ChtA-pCR2.1Topo (38) digested with HindIII/PstI into pDXA-HC digested with HindIII/NsiI. Ddatg8 was obtained by PCR with the primers GGGGATCCGTTCATGTATCAA and GGGGATCCTTATAAATCACTA and cloned into the BamHI restriction enzyme site of the RFPmars plasmid (7).

Gene disruption and plasmid transformations.

Cloning and disruption of the atg1, atg5, atg7, and atg8 genes have been described elsewhere, as have general methods of transformation and selection (26, 27).

Kinase assays.

Growing cells were pelleted, washed with SorC (16.7 mM Na2H/KH2PO4, 50 μM CaCl2, pH 6.0), and lysed in TENT lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100) with protease inhibitors (1 tablet of Roche Complete mini-protease inhibitor per 10 ml of TENT) at 107 cells/ml. Samples were rapidly frozen in dry ice and stored at −80ο C until use. Samples were thawed at 50ο C and spun at 4ο C for 15 min at 13,000 rpm in a benchtop centrifuge to remove the cell debris. Sixty microliters of glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) was added to the supernatant and mixed by gentle rotation at 4ο C for 1 h. The beads were pelleted at 500 × g for 2 min and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline. The beads were divided in two for a kinase assay and Western blotting, which served as a loading control. For the kinase assay, the beads were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and suspended in kinase buffer (20 mM morpholineethanesulfonic acid, pH 6.5, 3 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) (6). The beads were suspended in 40 μl of kinase buffer that contained 25 μM ATP and 25 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol, or 111 TBq/mmol; Perkin Elmer Easytides). After a 30-min incubation at room temperature, the reaction was terminated by adding protein gel electrophoresis buffer. The samples were then resolved in 10% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was dried, and radioactivity was detected by exposure to an X-ray film.

Fluorescence microscopy.

To determine the cellular distribution of the several versions of DdAtg1, GFP or RFP coding sequences were fused to the N terminus of the DdAtg1 coding sequence. The fusion genes were under the control of the actin15 promoter in pTX or pDXA plasmids.

Cells growing in HL5 were transferred to 35-mm glass-bottom microwell dishes (MatTek) in FM. The cells expressing GFP were observed in FM (growing cells) or after 2 h in SorC (starving cells) using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescence microscope. For colocalization experiments, cells expressing GFP-DdAtg1, GFP-DdAtg1K36A, GFP-DdAtg1Δ40, or GFP-DdAtg1K36AΔ40 were transformed with a construct expressing RFP-DdAtg8. Cells were starved in FM without amino acids for 2 h, flattened by a thin layer of agarose, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. The fluorescence was observed under a Zeiss 401-A LSM510 Meta confocal microscope.

Electron microscopy.

The electron microscopy protocol has been described previously (3). To estimate the number of autophagosomes formed, we defined an early or nascent autophagosome as a double-membrane-enclosed structure containing cytoplasm or organelles, where the outer and inner membranes are separated by an electron-lucent space and where the contents of the vacuole appear undigested. This definition corresponds with accepted morphology of an early autophagosome (see references 13 and 17 for examples). In some cases, more than one membrane may surround the engulfed contents. We defined an autophagolysosome or late autophagosome as a digestive vacuole, which sometimes lacks the inner delimiting membrane that surrounds engulfed material, the latter often showing evidence of degradation. In more advanced stages, only partially digested contents remain.

RESULTS

Structure of Dictyostelium Atg1.

DdAtg1 is a serine/threonine kinase homologous to the S. cerevisiae autophagy protein Atg1 (21, 34). The gene is composed of an N-terminal kinase domain (266 amino acids) and a C-terminal homology domain (122 amino acids) separated by a proline/serine-rich region (Fig. 1A). Mutation of a conserved lysine in the ATP-binding loop, position 46 in mouse and 54 in budding yeast Atg1, results in a kinase-negative protein, which behaves as a dominant-negative when overexpressed (14) (39). Mutation of a conserved proline to serine results in a temperature-sensitive kinase in other organisms (see below). The positions of the Dictyostelium K36A mutation that causes the dominant-negative phenotype and the P138S mutation that results in a temperature-sensitive DdAtg1 protein are indicated in Fig. 1A. The degrees of similarity between DdAtg1, the human (ULK2), and the C. elegans (UNC-51) homologues are shown (Fig. 1B). We were not able to find any known motifs in the C-terminal homology region (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/).

The kinase activity and the conserved C-terminal region of DdAtg1 are essential for DdAtg1 function in autophagy and development.

The S. cerevisiae Atg1 autophosphorylates and also phosphorylates myelin basic protein in vitro, and the mouse UNC51.1 also has autophosphorylation activity (14) (39). Other targets of Atg1, if any, are not known. To investigate the function of the DdAtg1 kinase domain, we constructed a kinase-negative protein by site-directed mutagenesis (see Methods). We also prepared a truncation mutant of the DdAtg1 protein to test the importance of the conserved C-terminal region in autophagy and development.

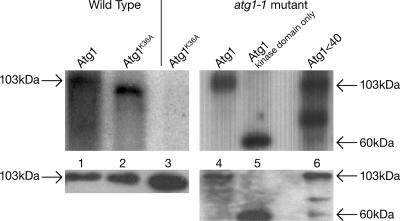

To confirm that DdAtg1K36A lacks kinase activity, a kinase assay was performed using the GST-tagged protein. We purified GST-tagged proteins after binding to glutathione beads and assayed autophosphorylation activity. Wild-type cells expressing the DdAtg1 plasmid showed autophosphorylation activity in both wild-type and atg1 null backgrounds (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 4). No autophosphorylation was observed for the kinase-negative protein in the atg1-1 null background (Fig. 2, lane 3). However, the kinase-negative protein is phosphorylated when it is expressed in the wild-type background (Fig. 2, lane 2). It migrates slightly faster than the control ATG1, perhaps because of a lesser degree of phosphorylation. The kinase domain (amino acids 2 to 266) and the DdAtg1Δ40 protein retained autophosphorylation activity, indicating that the C-terminal region does not regulate the autophosphorylation activity. After purification, the samples were divided in two, and half was used for phosphorylation assays, and the other half was used as a loading control for Western blotting (bottom panels). The Western blots show that all of the samples are expressed at the expected levels, although the truncated form tended to degrade.

FIG. 2.

DdAtg1K36A lacks kinase activity. Plasmids expressing GST-tagged DdAtg1 and DdAtg1K36A in wild-type DH1 (lanes 1 and 2) or atg1-null cells (lane 3). The proteins were purified by a pull-down with glutathione beads and assayed for autophosphorylation (top). The right lanes (lanes 4 to 6) show that a deletion of the C-terminal portion of the Atg1 kinase does not affect the kinase activity. Western blots (bottom) with anti-GST antibodies of the same samples are shown. DdAtg1K36A is not phosphorylated in the atg1-null background but is phosphorylated in the DH1 background (compare lane 3 to lane 2).

To test whether DdAtg1K36A rescues the developmental defect in atg1-1, we developed transformed mutant and wild type-cells on nitrocellulose filters. We confirmed that protein products of the predicted size were produced in transformed cells expressing GFP fusions by Western blotting using antibodies against GFP fused to mutant or wild-type DdAtg1 (data not shown). Overexpressing Atg1 does not affect the development of the wild-type cells and efficiently rescues the mutant phenotype of atg1-null cells (Fig. 3A, middle frames).

FIG. 3.

DdAtg1K36A does not rescue the developmental defect of the atg1-1 mutant and acts as a dominant negative in wild-type (DH1) cells. (A) DH1 (parental) and atg1-null cells expressing DdAtg1 or DdAtg1K36A were developed on nitrocellulose filters and photographed after 30 h. Cells expressing DdAtg1 formed normal-looking fruiting bodies (middle frames), but cells expressing DdAtg1K36A behave like atg1-null cells (right frames). (B) DH1 and atg1-1 cells expressing DdAtg1Δ40 with or without the K36A kinase-negative mutation were plated on nitrocellulose filters for development. Neither DdAtg1Δ40- nor DdAtg1K36AΔ40-expressing constructs are able to rescue the developmental defect of atg1-null cells, and DdAtg1K36AΔ40 no longer acts as dominant negative (upper right frame). Bar, 0.5 mm.

Kinase-negative DdAtg1K36A does not rescue the atg1-1 phenotype and shows dominant-negative activity in wild type, resulting in aggregation defects and a phenocopy of the atg1 mutant phenotype (Fig. 3A, right frames). atg1 mutant cells expressing the truncated DdAtg1 missing the last 40 amino acids (DdAtg1Δ40) were not rescued in development (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, parental DH1 cells expressing DdAtg1K36AΔ40 behaved like wild-type cells, showing that the conserved C-terminal region of DdAtg1 is required for the dominant-negative activity of the DdAtg1K36A protein (Fig. 3B, upper right frame). We conclude that the kinase activity and the conserved C-terminal region of DdAtg1 are necessary for Dictyostelium development.

We asked whether the kinase activity and the conserved C-terminal region of DdAtg1 are essential for autophagy, in addition to development. The atg1 null cells die more rapidly in amino acid-free medium than other autophagy mutants. We tested the ability of GFP-tagged kinase-negative DdAtg1 and DdAtg1Δ40 to rescue the survival of atg1-1 cells in amino acid-free medium (Fig. 4). GFP and GFP-DdAtg1K36A expression did not restore the survival of atg1-1 in amino acid-free medium, whereas GFP-Atg1-expressing cells survive like the parental DH1 cells. DH1 cells expressing GFP-Atg1K36A die rapidly in amino acid-free medium, suggesting that kinase-negative DdAtg1 acts through a dominant-negative mechanism and mimics the effect of the atg1-1 mutation in the DH1 strain. The atg1 null cells expressing the DdAtg1Δ40 and DdAtg1K36AΔ40 did not survive in the amino acid-free medium (Fig. 4B). DH1 cells expressing DdAtg1K36AΔ40 survived well in this medium, again showing that unlike the DdAtg1K36A protein, DdAtg1K36AΔ40 does not act as dominant negative.

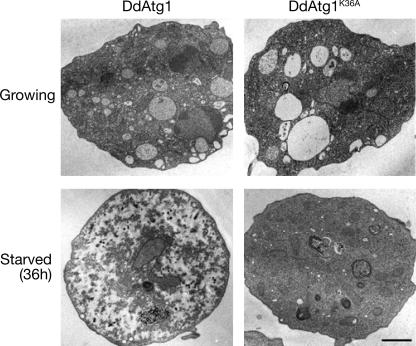

We confirmed that the kinase-negative protein behaves as a dominant negative in parental DH1 cells by TEM of amino acid-starved cells. DH1 cells expressing GFP-tagged wild-type or kinase-negative DdAtg1 were examined during growth or after 36 h of amino acid starvation. Growing cells of either strain were similar in the density of their cytoplasmic contents (Fig. 5, upper frames). The cytoplasm is filled with organelles, ribosomes, and glycogen. These results are consistent with those previously observed in the null mutant of atg1-1 (26). Starved DH1 cells that express DdAtg1 showed the expected signs of autophagy, with cytoplasm that appeared less electron-dense, some dark granular masses, and very few mitochondria or other organelles (Fig. 5, lower left frame). In contrast, DH1 cells that express DdAtg1K36A looked similar to growing cells, with a dense and organelle-rich cytoplasm and no signs of autophagy (Fig. 5, lower right frame). In the growing cells there are large vacuoles that disappear during the 36-h starvation period. These are likely to be the water-secreting contractile vacuoles (10) (5). Their disappearance does not depend on Atg1 activity.

FIG. 5.

Cellular contents are not degraded in the DdAtg1K36A-expressing mutant during starvation. DH1 cells expressing DdAtg1 or DdAtg1K36A were fixed after growth or after 36 h of starvation in growth medium without amino acids. Cells were sectioned and observed by TEM. As shown in the lower right frame, mitochondria and cytoplasm are not degraded in the cells expressing DdAtg1K36A after 36 h in amino-acid-free FM. Normal degradation during starvation is shown in the lower left panel. The large vacuoles observed in the upper frames are part of the contractile vacuole water-pumping system and are lost during starvation. Bar, 1 μm.

Immature autophagosomes are formed in the kinase-negative mutant during starvation.

We observed two additional ultrastructural phenomena with atg1 mutants starved for 36 h in nitrogen-free medium, both with the initial atg1-1 insertion mutant (28) and with the dominant-negative strain described above. We observed a significant number of nascent autophagosomes. These are rarely observed in wild-type cells (Table 1). Figure 6 shows examples of autophagosomes observed in cells that express dominant-negative DdAtg1K36A (Fig. 6C to F) and one image of an autophagosome (or autophagolysosome) from a wild-type cell (Fig. 6D). Some of the mutant autophagosomes are not completely closed and appear in ultrathin sections as a “C-shaped” membranous structure with a bulbous tip (Fig. 6E). We cannot say whether these structures close like a purse or are more complicated cylindrical structures, but we suggest that these structures correspond to the isolation membranes in mammalian cells. The cytoplasmic content appears similar to the content on the exterior of the structures, and the presence of double membranes is also notable.

TABLE 1.

DdAtg1K36A-expressing cells have an increased number of immature autophagosomes

| Sample | No. of autophagosomal structures/section |

|---|---|

| DH1 (atg1) | 0.50 ± 0.1 |

| DH1 (atg1K36A) | 2.50 ± 0.4 |

| atg5− | 0.16 ± 0.4 |

| atg1− | 3.3 ± 2.5 |

The numbers of autophagosomal structures were counted in the starved cells expressing DdAtg1 or DdAtg1K36A or in atg5− and atg1− cells. Autophagosomal structures in sections from 51 cells were counted for each strain. Standard deviations are shown. See Materials and Methods for criteria.

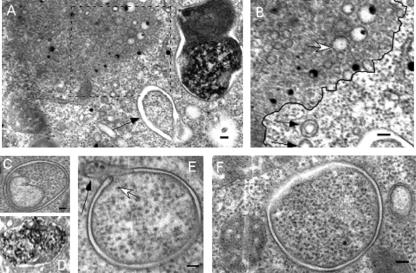

FIG. 6.

Nascent autophagosomes are observed in the Atg1K36A dominant-negative mutant. High magnification views of the cellular structures from the TEM images of the cells expressing DdAtg1K36A. (A) Nascent autophagosomes (arrow) are commonly observed at the periphery of vesicles. (B) Higher magnification view of blocked (dashed line) area in panel A. Large collections of vesicles are found in these cells, some with double membranes (black arrows), and others with single membranes (white arrow). A black line has been drawn separating the two zones. (C to F) Examples of forming and early autophagosomes. A nascent autophagosome is marked with a white arrow in panel E. A closing autophagosome with a bulbous tip is shown with a black arrow in panel E. The autophagosome in panel D is from wild-type DH1 cells expanded from the lower left frame of Fig. 5. Bar, 0.1 μm.

To confirm and quantify this observation, we counted the number of autophagosomes in starved cells. We defined a nascent autophagosome as a double-membrane-enclosed structure containing cytoplasm or organelles, where the outer and inner membranes are separated by an electron-lucent space and where the contents of the vacuole appear undigested (Table 1) (examples of autophagosomes can be found in references 13 and 17). We expected to find no autophagosomes formed in the atg1-null and DdAtg1K36A mutants, but we consistently observed a significant number of nascent autophagosomes. If the cells are starved for 36 h, parental DH1 cells expressing wild-type DdAtg1 had 0.50 ± 0.1 autophagosomes per TEM section in 51 cells examined. The DH1 cells expressing kinase-negative DdAtg1K36A had 2.50 ± 0.4 autophagosomes per TEM section in 51 observed cells (see Materials and Methods for details). This phenomenon is not typical for all of the autophagy mutants since another Dictyostelium autophagy mutant, atg5−, had fewer autophagosomes (0.16 ± −0.4), and these were small compared to the other two strains (Table 1).

In addition to autophagosomes, we observed the same large collections of small vesicles inside an electron-dense region (Fig. 6A and B) as in atg1-1 cells. We observed single- and double-membrane vesicles. The double-membrane vesicles appear only outside the electron-dense region. Inside the electron-dense region, the vesicles have only a single membrane. These occupy a significant volume of the cell and often have early or forming autophagosomes closely associated. We do not know the nature of this population of vesicles. We suggest that the loss of DdAtg1 or of its kinase activity may affect autophagosome fusion with vesicles that are necessary for maturation.

The kinase-negative DdAtg1K36A colocalizes with the canonical marker of autophagosomes, DdAtg8.

GFP-tagged DdAtg1 and DdAtg1K36A were expressed in DH1 (parental) and atg1-1 strains to observe their localization. In budding yeast, Atg1 localizes to the PAS, typically a single spot in cells (36). DdAtg1, under the control of a constitutive actin15 promoter, showed only diffuse cytoplasmic background under both growth and starvation conditions; no punctate structures were observed after 2 h of starvation in SorC buffer (Fig. 7A, far left frames). In contrast, DdAtg1K36A-expressing cells had localized spots of GFP fluorescence in addition to cytoplasmic localization in both DH1 and atg1-1 backgrounds (Fig. 7A). The fluorescence in these structures was not homogenous, and they contained bright punctate areas. The same structures were also observed in growing GFP-DdAtg1K36A-expressing cells but not in growing GFP-DdAtg1-expressing cells (not shown). We observed the same localization pattern in growing and starving atg5−, atg7−, and atg8− mutants expressing GFP-DdAtg1K36A (data not shown). Thus, the localization of the kinase-negative protein to punctate structures does not depend on DdAtg5, DdAtg7, or DdAtg8, which are components of a ubiquitin-like conjugation system that is essential for autophagy. Cells expressing DdAtg1K36AΔ40 showed a very strong punctate localization, unlike the weak signal of the localization of DdAtg1K36A (Fig. 7A, far right frames). Irrespective of the genetic background, accumulation of the kinase-negative protein is comparable to that of GFP-DdAtg1 as determined by Western blotting with an anti-GFP antibody (data not shown). This stabilization or oversynthesis of the mutant protein may be one reason that it accumulates in these nonautophagic structures.

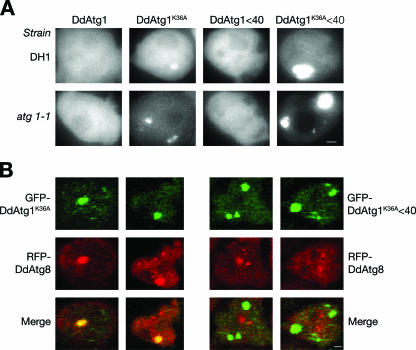

FIG. 7.

GFP-ATG1K36A colocalizes with RFP-DdAtg8. (A) DH1 and atg1-null cells expressing GFP-DdAtg1, GFP-DdAtg1K36A, GFP-DdAtg1Δ40, or GFP-DdAtg1K36AΔ40 were starved in FM without amino acids for 2 h and observed under a fluorescence microscope. Note punctate localization of DdAtg1K36A. (B) DH1 cells were transformed with GFP-DdAtg1K36A and RFP-DdAtg8 or GFP-DdAtg1K36AΔ40 and RFP-DdAtg8. These cells were starved for 2 h, flattened by a thin layer of agarose, fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and observed with a confocal microscope. Note colocalization of DdAtg1K36A and DdAtg8. Bar, 1 μm.

Next, we asked whether DdAtg1K36A colocalizes with the marker of autophagosomes, DdAtg8. We transformed DH1 cells with plasmids expressing GFP-DdAtg1K36A or GFP-DdAtg1K36AΔ40 and RFP-DdAtg8, flattened the cells with a thin layer of agarose, fixed them, and observed them by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Two examples are shown for each cell type. DdAtg1K36A is colocalized with DdAtg8 on dilated structures similar to those observed for GFP-DdAtg1K36A (Fig. 7B, left frames). The C-terminal conserved region of DdAtg1 is required for this localization because DdAtg1K36AΔ40 does not colocalize with RFP-DdAtg8 (Fig. 7B, right frames). DdAtg8 is localized to punctate structures in wild-type cells; however, this localization patterns changes, and DdAtg8 is localized to more dilated structures in autophagy mutants, including atg1 mutant cells.

Atg1 activity is required throughout Dictyostelium development.

We asked whether autophagy is required throughout development, how long the cells can develop after autophagy is blocked, and whether such a block is reversible. We created a temperature-sensitive mutant of Atg1 by changing the proline residue at position 138 to serine (Fig. 1A). The mutation was described first by Carr and colleagues, who showed that a mutation of proline 137 to serine in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe cdc2 gene results in a temperature-sensitive phenotype and causes cell cycle arrest when shifted to restrictive temperature (4). Hsu and Perrimon showed that the same mutation in the conserved proline 210 caused a temperature-sensitive phenotype in the MEK dual-specificity threonine/tyrosine kinase in Drosophila (11). Gaskins and colleagues used the method to construct a temperature-sensitive Erk2 mitogen-activated protein kinase in D. discoideum (9).

When transformed into the atg1-1 mutant, the DdAtg1P138S (temperature-sensitive Atg1 [Atg1ts])-expressing plasmid complements the developmental defect at 20°C but not at 27°C, which is the restrictive temperature for Dictyostelium (Fig. 8A). The wild-type DdAtg1 complements the developmental defect of atg1-1 at both 20°C and 27°C, although less efficiently at 27°C (Fig. 8A, upper frames). Except for a few rudimentary aggregates, the null cells carrying the DdAtg1ts allele did not develop at the restrictive temperature. For these experiments, cells were grown at 27°C in HL5 growth medium for 1 day before the experiment to inactivate residual DdAtg1.

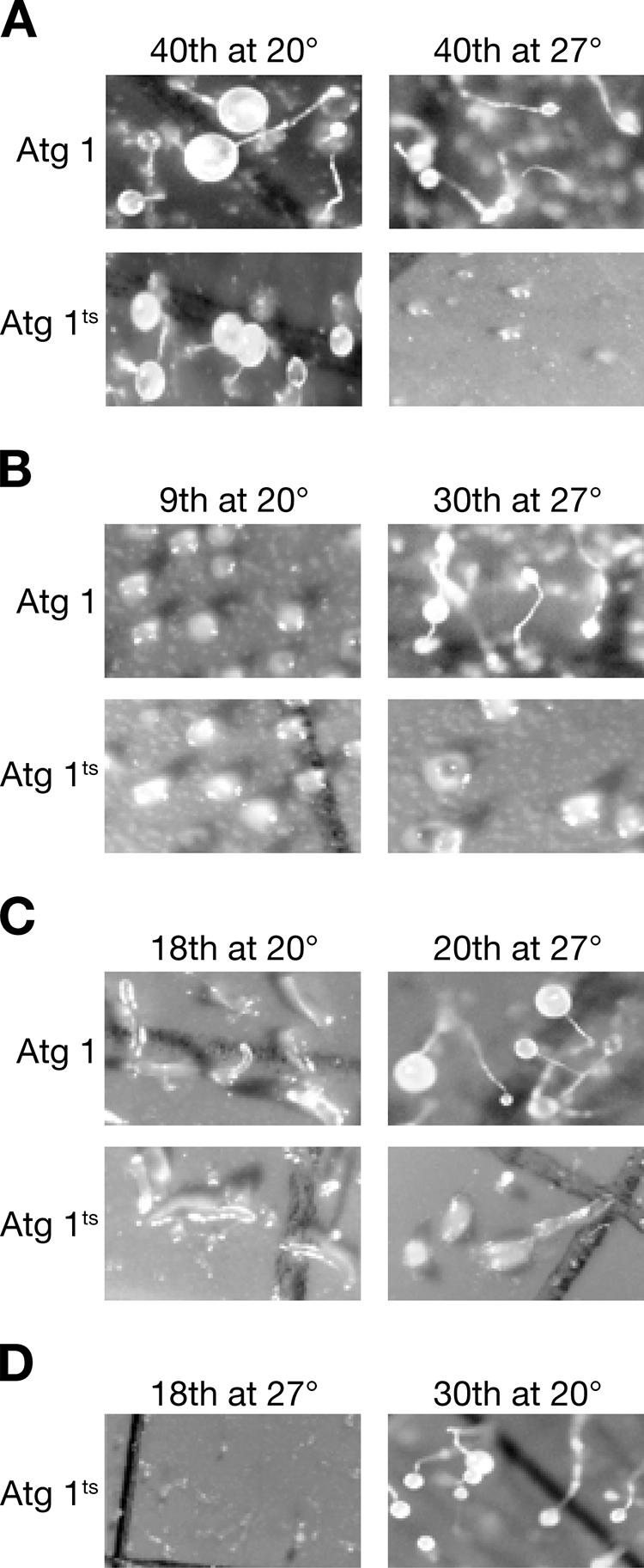

FIG. 8.

DdAtg1 is required throughout development. atg1-1 null cells were transformed with wild-type plasmid or a plasmid coding for a temperature-sensitive atg1. (A) Temperature-sensitive cells (DdAtg1ts) did not develop at 27°C but formed fruiting bodies at 20°C. (B) The same cells were developed for 9 h at 20°C, at which time they had formed aggregates (left frames). They were then shifted to 27°C. Cells expressing the temperature-sensitive Atg1 did not progress, while those expressing the wild-type gene formed fruiting bodies (right frames). (C) DdAtg1ts cells that had formed slugs after 18 h stopped development when shifted to the restrictive temperature, while the controls continued development to form fruiting bodies. (right frames). (D) Reversibility was tested by shifting cells that had failed to develop at 27°C to 20°C.

To determine the importance of DdAtg1 at the aggregation stage, we performed temperature-shift experiments. We developed atg1-1 cells expressing DdAtg1 or DdAtg1ts proteins at 20°C for 9 h and transferred them to 27°C. At that time the cells of both populations had formed mounds of cells, as shown in Fig. 8B (left frames). After a further 30 h of development at 27°C, DdAtg1-expressing cells had formed fruiting bodies, whereas DdAtg1ts-expressing cells remained arrested at the mound stage, showing little progression (Fig. 8B, right frames). To investigate the requirement for DdAtg1 function at the slug stage (18 h of development), we performed a shift-up experiment. The left frames in Fig. 8C show the slugs at the time of shift to 27°C. Twenty hours later the transformants harboring the plasmid with the wild-type sequence had formed fruiting bodies, but the DdAtg1ts cells were arrested at the slug stage (Fig. 8C, right frames).

A shift-down experiment showed that the inhibition of development is reversible. At the time of the shift-down, DdAtg1ts cells kept at 27°C had not aggregated (Fig. 8D), but after a further 24 h at 20°C, they had made normal fruiting bodies. The results suggest that Atg1 and the autophagy pathway in general are necessary throughout the development of Dictyostelium. We infer from these data that cells may not have a large reserve of energy and metabolites and that the rate of autophagy is coordinated with the energy needs of development.

DISCUSSION

In the current work, we have further characterized the D. discoideum serine/threonine kinase Atg1. DdAtg1 kinase has a C-terminal domain that is conserved in the C. elegans, mouse, and human Atg1 homologues (Fig. 1B). We used a kinase-negative DdAtg1 in which lysine 36 was changed to alanine, a temperature-sensitive DdAtg1 in which proline 138 was mutated to serine, and truncation mutants to analyze DdAtg1 function.

Studies in S. cerevisiae have shown that a number of proteins interact with Atg1 and control the choice between the CVT pathway and autophagy (reviewed in reference 15). The genes that code for some of these interacting proteins, which include Atg13, Atg17, and Atg23, are not detected in the genomes of Dictyostelium or in animals. ATG23 is CVT specific and therefore might not be expected to occur in Dictyostelium, but the absence of the other proteins caused us to ask whether regulation of Atg1 in D. discoideum is different from budding yeast.

Our results suggest that the kinase activity and the conserved C-terminal region are essential for DdAtg1 function during autophagy and development. When expressed in wild-type cells, DdAtg1K36A acts as a dominant-negative protein and produces the same phenotype as the atg1-null cells (Fig. 3A and 4A). The C. elegans UNC-51 and mouse UNC51.1 proteins also have dominant-negative activity when mutated in the kinase domain, causing neurological defects (25, 39). The DdAtg1 homologue of C. elegans, UNC-51, forms homo-oligomers (24). However, the dominant-negative activity of DdAtg1K36A is lost when part of the C-terminal conserved region is removed (Fig. 3B and 4B), which implies that the C-terminal conserved region is required for DdAtg1K36A to exert its dominant-negative activity, possibly by regulating its association with other proteins or membranous structures. The C. elegans Atg1 homologue, UNC-51, interacts with the UNC-14 protein through its C-terminal domain (24). We were not able to find a homologue of UNC-14 in the completely sequenced Dictyostelium genome.

The TEM data show that the DdAtg1 kinase-negative mutant is defective in turnover of its cytoplasmic contents, like the atg1-null and other autophagy mutants (Fig. 5) (26, 27). They have undegraded cytoplasm and a significant number of mitochondria. Expression of the kinase-negative DdAtg1 protein in DH1 cells also phenocopies the atg1-1 mutation with respect to the large vesicle clusters observed in an electron-dense region in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A). This region contains many small vesicles but is not membrane bound. Inside this region, the vesicles have a single membrane; outside they have double membranes (Fig. 6B; a black line has been drawn to separate the two regions). This region may be the dilated structure we observe by immunofluorescence in Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 6C, E, and F, nascent autophagosomes are found in DdAtg1K36A-expressing cells as well as in atg1-1 cells. We counted the number of early and late autophagosomes in different starving autophagy mutants. There were almost no autophagosomes present in the atg5 mutant. DdAtg1K36A-expressing cells and atg1-1 mutant cells have an increased number of these autophagosomes, and they appear to be arrested during formation or maturation. The significant increase in the number of nascent autophagosomes suggests that DdAtg1 may not be essential for autophagosome formation but may be required for later stages of autophagosome maturation. It is also possible that there is a redundancy in autophagosome formation, with another Atg1 homologue functionally substituting for DdAtg1 in atg1 mutant cells but unable to fulfill DdAtg1 function(s) later in autophagosome maturation.

The kinase-negative DdAtg1 is mislocalized to dilated structures during growth and starvation, unlike the diffuse cytoplasmic localization of the wild-type protein (Fig. 7A). At this dilated structure, kinase-negative DdAtg1 colocalizes with the autophagy marker DdAtg8, which is lost in the cells expressing DdAtg1K36AΔ40 (Fig. 7B). Because of colocalization with DdAtg8, the dilated structures labeled by DdAtg1K36A appear to be autophagosomes, but we do not know the nature of the observed structures labeled with DdAtg1K36AΔ40. They could be nonspecific cytoplasmic aggregates. Based on these results we propose that the conserved C-terminal region of DdAtg1 is required for its association with autophagosomal structures or the PAS. After recruitment to these structures, through its kinase activity DdAtg1 is recycled from the membrane, since the kinase-negative DdAtg1K36A is arrested at dilated structures that also contain DdAtg8. This model also explains the dominant-negative activity of DdAtg1K36A and the lack of this activity in the cells expressing DdAtg1K36AΔ40. We propose that, DdAtg1K36A, when arrested at these dilated structures, prevents association of endogenous DdAtg1 by blocking all available binding sites on these structures, resulting in inhibition of DdAtg1 function and an atg1-null phenotype in the wild-type background. In the wild-type cells expressing DdAtg1K36AΔ40, the dominant-negative activity is lost because DdAtg1K36AΔ40 is not able to associate with the dilated structure, allowing wild-type DdAtg1 to perform its function. In line with our results, Atg1 is important for the retrieval of Atg9 and Atg23 from the PAS in budding yeast (31). DdAtg1 may help shuttling of DdAtg9 or another autophagy protein between the mitochondria and the preautophagosomal structure (29, 30).

Substitution of proline 138 to serine resulted in a temperature-sensitive DdAtg1 protein. The experiments with DdAtg1ts suggest that DdAtg1 is required throughout development and not only in the early stages when nutrient retrieval/recycling would be expected to be especially important (Fig. 8). Even if DdAtg1 activity is inhibited by temperature shift after 16 h into development, slugs are arrested at that stage and do not progress. This result is consistent with the idea that a constant turnover of proteins and organelles is required to obtain the molecular constituents and energy needed for development. If there were a reserve of material and energy accumulated during growth, we would expect the aggregates to progress in development, which does not appear to be the case. Another explanation is that a pathway independent from autophagy regulated by DdAtg1 is required for progression of development in the later stages.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kessin laboratory for helpful discussions and assistance. We thank Ayse Tekinay for technical assistance and Clement Nizak for helpful discussions. We thank the Dictyostelium Stock Center for the strains and plasmid supplied (www.dictybase.org).

Part of this work was supported by NIH grant GM33136-19.

Footnotes

This is Lamont-Doherty contribution number 6949.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abeliovich, H., W. A. Dunn, Jr., J. Kim, and D. J. Klionsky. 2000. Dissection of autophagosome biogenesis into distinct nucleation and expansion steps. J. Cell Biol. 151:1025-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abeliovich, H., C. Zhang, W. A. Dunn, Jr., K. M. Shokat, and D. J. Klionsky. 2003. Chemical genetic analysis of Apg1 reveals a non-kinase role in the induction of autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:477-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, O. R. 1994. Fine structure of the marine amoeba Vexillifera telmathalassa collected from a coastal site near Barbados with a description of salinity tolerance, feeding behavior and prey. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 41:124-128. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr, A. M. and. Nurse, P. 1989. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of mutant alleles of the fission yeast cdc2 protein kinase gene: implications for cdc2+ protein structure and function. Mol. Gen. Genet. 218:41-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke, M., and J. Heuser. 1997. Water and ion transport, p. 75-91. In Y. Maeda, K. Inouye, and I. Takeuchi (ed.), Dictyostelium: a model system for cell and developmental biology. Universal Academy Press, Tokyo, Japan.

- 6.Durgerian, S., and S. S. Taylor. 1989. The consequences of introducing an autophosphorylation site into the type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 264:9807-9813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer, M., I. Haase, E. Simmeth, G. Gerisch, and A. Muller-Taubenberger. 2004. A brilliant monomer red fluorescent protein to visualize cytoskeleton dynamics in Dictyostelium. FEBS Lett. 577:227-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Funakoshi, T., A. Matsuura, T. Noda, and Y. Ohsumi. 1997. Analyses of APG13 gene involved in autophagy in yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 192:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaskins, C., A. M. Clark, L. Aubry, J. E. Segall, and R. A. Firtel. 1996. The Dictyostelium MAP kinase ERK2 regulates multiple, independent developmental pathways. Genes Devel. 10:118-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heuser, J., Q. L. Zhu, and M. Clarke. 1993. Proton pumps populate the contractile vacuoles of Dictyostelium amoebae. J. Cell Biol. 121:1311-1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu, J. C., and N. Perrimon. 1994. A temperature-sensitive MEK mutation demonstrates the conservation of the signaling pathways activated by receptor tyrosine kinases. Genes Dev. 8:2176-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabeya, Y., Y. Kamada, M. Baba, H. Takikawa, M. Sasaki, and Y. Ohsumi. 2005. Atg17 functions in cooperation with Atg1 and Atg13 in yeast autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:2544-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabeya, Y., N. Mizushima, A. Yamamoto, S. Oshitani-Okamoto, Y. Ohsumi, and T. Yoshimori. 2004. LC3, GABARAP and GATE16 localize to autophagosomal membrane depending on form-II formation. J. Cell Sci. 117:2805-2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamada, Y., T. Funakoshi, T. Shintani, K. Nagano, M. Ohsumi, and Y. Ohsumi. 2000. Tor-mediated induction of autophagy via an Apg1 protein kinase complex. J. Cell Biol. 150:1507-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamada, Y., T. Sekito, and Y. Ohsumi. 2004. Autophagy in yeast: a TOR-mediated response to nutrient starvation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 279:73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessin, R. H., et al. (ed.). 2001. Dictyostelium: evolution, cell biology, and the development of multicellularity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 17.Komatsu, M., S. Waguri, T. Ueno, J. Iwata, S. Murata, I. Tanida, J. Ezaki, N. Mizushima, Y. Ohsumi, Y. Uchiyama, E. Kominami, K. Tanaka, and T. Chiba. 2005. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 169:425-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuroyanagi, H., J. Yan, N. Seki, Y. Yamanouchi, Y. Suzuki, T. Takano, M. Muramatsu, and T. Shirasawa. 1998. Human ULK1, a novel serine/threonine kinase related to UNC-51 kinase of Caenorhabditis elegans: cDNA cloning, expression, and chromosomal assignment. Genomics 51:76-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levi, S., M. Polyakov, and T. T. Egelhoff. 2000. Green fluorescent protein and epitope tag fusion vectors for Dictyostelium discoideum. Plasmid 44:231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manstein, D. J., H. P. Schuster, P. Morandini, and D. M. Hunt. 1995. Cloning vectors for the production of proteins in Dictyostelium discoideum. Gene 162:129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuura, A., M. Tsukada, Y. Wada, and Y. Ohsumi. 1997. Apg1p, a novel protein kinase required for the autophagic process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 192:245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melendez, A., Z. Talloczy, M. Seaman, E. L. Eskelinen, D. H. Hall, and B. Levine. 2003. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science 301:1387-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizushima, N., A. Kuma, Y. Kobayashi, A. Yamamoto, M. Matsubae, T. Takao, T. Natsume, Y. Ohsumi, and T. Yoshimori. 2003. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12-Apg5 conjugate. J. Cell Sci. 116:1679-1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogura, K., M. Shirakawa, T. M. Barnes, S. Hekimi, and Y. Ohshima. 1997. The UNC-14 protein required for axonal elongation and guidance in Caenorhabditis elegans interacts with the serine/threonine kinase UNC-51. Genes Dev. 11:1801-1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogura, K., C. Wicky, L. Magnenat, H. Tobler, I. Mori, F. Muller, and Y. Ohshima. 1994. Caenorhabditis elegans unc-51 gene required for axonal elongation encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase. Genes Dev. 8:2389-2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otto, G. 2003. Macroautophagy is required for multicellular development of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. PhD. Dissertation. Columbia University, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Otto, G. P., M. Y. Wu, M. Clarke, H. Lu, O. R. Anderson, H. Hilbi, H. A. Shuman, and R. H. Kessin. 2004. Macroautophagy is dispensable for intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila in Dictyostelium discoideum. Mol. Microbiol. 51:63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otto, G. P., M. Y. Wu, N. Kazgan, O. R. Anderson, and R. H. Kessin. 2004. Dictyostelium macroautophagy mutants vary in the severity of their developmental defects. J. Biol. Chem. 279:15621-15629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reggiori, F., and D. J. Klionsky. 2006. Atg9 sorting from mitochondria is impaired in early secretion and VFT-complex mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 119:2903-2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reggiori, F., T. Shintani, U. Nair, and D. J. Klionsky. 2005. Atg9 cycles between mitochondria and the pre-autophagosomal structure in yeasts. Autophagy 1:101-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reggiori, F., K. A. Tucker, P. E. Stromhaug, and D. J. Klionsky. 2004. The Atg1-Atg13 complex regulates Atg9 and Atg23 retrieval transport from the pre-autophagosomal structure. Dev. Cell 6:79-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott, S. V., D. C. Nice, 3rd, J. J. Nau, L. S. Weisman, Y. Kamada, I. Keizer-Gunnink, T. Funakoshi, M. Veenhuis, Y. Ohsumi, and D. J. Klionsky. 2000. Apg13p and Vac8p are part of a complex of phosphoproteins that are required for cytoplasm to vacuole targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25840-25849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stege, J. T., M. T. Laub, and W. F. Loomis. 1999. Tip genes act in parallel pathways of early Dictyostelium development. Dev. Genet. 25:64-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Straub, M., M. Bredschneider, and M. Thumm. 1997. AUT3, a serine/threonine kinase gene, is essential for autophagocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 179:3875-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sussman, M. 1987. Cultivation and synchronous morphogenesis of Dictyostelium under controlled experimental conditions. Meth. Cell Biol. 28:9-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki, K., T. Kirisako, Y. Kamada, N. Mizushima, T. Noda, and Y. Ohsumi. 2001. The pre-autophagosomal structure organized by concerted functions of APG genes is essential for autophagosome formation. EMBO J. 20:5971-5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki, K., T. Noda, and Y. Ohsumi. 2004. Interrelationships among Atg proteins during autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 21:1057-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tekinay, T., H. L. Ennis, M. Y. Wu, M. Nelson, R. H. Kessin, and D. I. Ratner. 2003. Genetic interactions of the E3 ubiquitin ligase component FbxA with cyclic AMP metabolism and a histidine kinase signaling pathway during Dictyostelium discoideum development. Eukaryot. Cell 2:618-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomoda, T., R. S. Bhatt, H. Kuroyanagi, T. Shirasawa, and M. E. Hatten. 1999. A mouse serine/threonine kinase homologous to C. elegans UNC51 functions in parallel fiber formation of cerebellar granule neurons. Neuron 24:833-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White, G. J., and M. Sussman. 1961. Metabolism of major cell components during slime mold morphogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 53:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan, J., H. Kuroyanagi, A. Kuroiwa, Y. Matsuda, H. Tokumitsu, T. Tomoda, T. Shirasawa, and M. Muramatsu. 1998. Identification of mouse ULK1, a novel protein kinase structurally related to C. elegans UNC-51. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 246:222-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan, J., H. Kuroyanagi, T. Tomemori, N. Okazaki, K. Asato, Y. Matsuda, Y. Suzuki, Y. Ohshima, S. Mitani, Y. Masuho, T. Shirasawa, and M. Muramatsu. 1999. Mouse ULK2, a novel member of the UNC-51-like protein kinases: unique features of functional domains. Oncogene 18:5850-5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]